1. Introduction

Maize (

Zea mays L.) occupies a prominent position worldwide, being not only the most widely cultivated cereal but also one of the crops of greatest economic and social importance [

1]. In addition to being a staple for human and animal consumption, maize plays a key role in industry and biofuel production, particularly in maize-based ethanol. During the 2024/2025 growing season, Brazil produced approximately 130 million tons of maize, consolidating its position as the third-largest producer worldwide, behind only the United States and China [

2]. This crop exerts a major impact on the national economy, contributing substantially to exports and to domestic supply chains, particularly those related to animal protein and biofuel production.

Although maize productivity has been widely investigated, hybrid responses to planting density remain highly genotype-dependent and environment-specific. Most studies evaluate only a small number of hybrids or focus on a single environment, limiting the extrapolation of findings to regions with contrasting edaphoclimatic conditions. In addition, few studies simultaneously assess multiple hybrids across different planting densities and production environments, restricting the understanding of hybrid-specific morphophysiological responses under varying levels of intraspecific competition. Therefore, research integrating hybrid performance, density responses, and environmental variation is essential to support more precise recommendations for growers and breeding programs.

Maize grain yield is a complex quantitative trait influenced by interactions among genetic, environmental, and management factors [

3]. Genetic improvement, combined with technological advances, has enabled the development of genotypes with high productive potential, whereas management practices aim to create optimal conditions for the expression of this potential [

4]. Among these management factors, plant population density and spatial arrangement have received increasing attention, as they directly influence light interception, resource competition, and, consequently, productivity [

5].

Recent studies have confirmed that maize grain yield responds strongly to plant density, with higher densities generally increasing yield up to a certain threshold, although the magnitude of response varies depending on genotype and environmental conditions [

6]. Achieving significant gains in maize productivity requires improving photosynthetic efficiency, which is directly related to the interception of photosynthetically active radiation. This process can be optimized by adjusting the spatial distribution of plants in the field, enhancing the conversion of solar energy into dry matter and, consequently, into grain yield [

7]. Li et al. [

8] demonstrated that higher plant densities enhance leaf area index and radiation use efficiency, whereas Bassu et al. [

9] observed that reducing inter-row spacing significantly increased the number of grains per unit area in a Mediterranean environment.

In this context, studying plant population density and spatial arrangement becomes a fundamental approach for determining the optimal number of plants per unit area, thereby maximizing the performance of each hybrid [

10]. Plant density exerts a direct influence on agronomic performance: at low densities, solar radiation is underutilized, leading to reduced productivity, whereas excessively high densities increase intraspecific competition for light, water, and nutrients, thereby limiting ear development and grain filling [

11,

12]. Carvalho et al. [

13], for instance, highlighted that plant populations of approximately 7–8 plants m

2 provide better area utilization, whereas Gao [

14] reported consistent yield increases with higher densities. From an economic perspective, Lacasa et al. [

15] demonstrated that the optimal density point may vary according to seed cost and grain price, emphasizing the importance of integrating agronomic and economic feasibility in decision-making.

The adoption of practices such as reduced row spacing and increased plant population has led to significant gains in maize productivity by optimizing the use of resources such as water, light, and nutrients, while minimizing morphological and reproductive losses [

16,

17,

18]. However, there is an optimal plant density threshold that depends on the genetic traits of the hybrid, edaphoclimatic conditions, and management practices adopted [

19]. Beyond this threshold, further increases in density lead to progressive yield declines [

12,

20].

Despite advances in maize breeding and management practices, the optimal plant density for maximizing yield still depends on genotype-specific responses and local environmental conditions. Few studies, however, have simultaneously evaluated multiple hybrids across different densities and environments [

5,

6]. Therefore, understanding how distinct maize hybrids respond to varying planting densities is essential for optimizing grain yield and resource use efficiency. We hypothesize that increasing plant density enhances overall grain yield, although the magnitude of this response varies among hybrids due to their morphophysiological characteristics.

Given this scenario, the present study aimed to evaluate the agronomic performance and spatial efficiency of maize hybrids developed by the UENF maize breeding program, comparing them with commercial materials under the edaphoclimatic conditions of the North and Northwest Fluminense regions, with the goal of maximizing grain yield through adjustments in plant population density and spatial arrangement.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

The plant material used in this study consisted of eight maize genotypes. Five hybrids were developed by the maize breeding program of the Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense Darcy Ribeiro (UENF): UENF MSV 2210, UENF MS 2208, UENF 506-6, UENF 506-11, and UENF 506-16. In addition, three commercially available genotypes were included as checks: the hybrids AG 1051 and BM 3061, and the open-pollinated variety BR 106. The maturity groups of the hybrids followed FAO classifications, ensuring representation of different growth cycles.

2.2. Experimental Conditions

Field experiments were conducted in two locations during the 2019/2020 growing season: one at the Colégio Estadual Agrícola Antônio Sarlo, in Campos dos Goytacazes (Northern Fluminense region, located 13 m asl, with geographic coordinates of 21°45′16″ South and 41°19′28″ West, mean annual precipitation of 1073 mm, and mean annual temperature of 23.6 °C), and Ilha Barra do Pomba Experimental Station, in Itaocara (Northwestern Fluminense region, located 60 m asl, with geographic coordinates of 21°40′09″ South and 42°04′36″ West, mean annual precipitation of 1221 mm, and mean annual temperature of 23.0 °C). Sowing was carried out in November 2019 and harvesting in March 2020, corresponding to the main grain maize season (October to January), which presents favorable climatic conditions for crop development. The two experimental sites were chosen for their contrasting edaphoclimatic conditions and representativeness of local maize production. Although daily climatic records were unavailable, temperature and precipitation showed little variation throughout the crop cycle; therefore, only mean values are presented.

The experiment followed a randomized complete block design with split plots and three replications. The main plots consisted of four row spacings, corresponding to the following plant population densities: 0.50 m (100,000 plants ha−1), 0.60 m (83,333 plants ha−1), 0.75 m (66,667 plants ha−1), and 1.00 m (50,000 plants ha−1). The subplots comprised eight genotypes: five hybrids developed by the UENF maize breeding program (UENF 506-6, UENF 506-11, UENF 506-16, UENF MS 2208, and UENF MSV 2210) and three commercial controls (AG 1051, BM 3061, and BR 106). Each subplot consisted of a single 3.0 m row, with 0.20 m spacing between plants, totaling 15 plants. Each plot contained 24 rows, representing the combinations of genotypes within each row spacing treatment.

Sowing was carried out manually, placing three seeds per hill at a depth of 5.0 cm, followed by thinning 20 days after emergence, leaving one plant per hill. The cultivation system adopted was conventional. Based on soil analysis, basal fertilization was applied according to crop recommendations, using an NPK 04-14-08 formulation, with doses proportional to plant population: 25 g m−1 for 100,000 plants ha−1, 30 g m−1 for 83,333 plants ha−1, 37.5 g m−1 for 66,667 plants ha−1, and 50 g m−1 for 50,000 plants ha−1. The first topdressing was performed 30 days after planting with NPK 20-00-20 at rates of 15 g m−1, 18 g m−1, 22.5 g m−1, and 30 g m−1 for the respective plant populations. The second topdressing was applied 45 days after planting using urea, at rates of 10 g m−1, 12 g m−1, 15 g m−1, and 20 g m−1 for 100,000, 83,333, 66,667, and 50,000 plants ha−1, respectively.

During plant development, crop management practices were carried out according to recommended guidelines for maize cultivation [

3].

2.3. Evaluated Traits

The following traits were evaluated: leaf greenness index (SPAD), measured on five plants per plot at the middle third of the last fully expanded leaf (first leaf above the ear), considering the average of three readings per leaf at the R1 stage and prior to senescence. A SPAD-502 chlorophyll meter (Konica Minolta Inc., Osaka, Japan) was used, which allows rapid and non-destructive readings of chlorophyll content, serving as a good indirect indicator of leaf nitrogen concentration [

21,

22]; plant height (PH), measured from the soil surface to the tassel insertion node, in meters; ear height (EH), measured from the soil surface to the insertion of the first ear on the stalk, in meters; ear length (EL), obtained as the average of six randomly selected ears, in centimeters; ear diameter (ED), obtained as the average of six ears using a digital caliper, expressed in millimeters; 100-grain weight (GW100), determined by weighing a sample of 100 healthy grains on a precision scale, in grams; and grain yield (GY) was determined by weighing the grains after shelling, correcting for 13% moisture content, and converting the values to kg ha

−1 based one plot area.

PH and EH were measured on six plants per plot, 80 days after sowing, while harvest was carried out at 120 days, collecting all ears from the useful plot. Other traits, such as flowering, number of plants per plot (stand), number of ears per hectare, number of rows per ear, and ear weight, were monitored to follow plant development but are not presented in this article because they did not show significant differences among treatments [

23].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

A joint analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed for each trait. Estimates of mean squares, overall mean, genotypic variability, genotypic determination coefficient, and experimental coefficient of variation were also calculated for all evaluated traits. Treatment means were compared using Tukey’s test [

24] at a 5% probability level whenever a significant effect of the respective source of variation (density or genotype) was detected. Experimental precision was evaluated through the experimental coefficient of variation (CVe), as recommended in previous studies [

25,

26]. The joint analysis of variance was conducted according to the following statistical model:

where

is the observation in the

k-th replication, evaluated in the

i-th environment,

j-th density, and

l-th genotype;

is the overall mean of the experiment;

is the effect of the

k-th replication within the

i-th environment, assumed to follow a normal distribution ~ NID (0,

);

is the fixed effect of the

i-th environment;

is the fixed effect of the

j-th density;

is the fixed effect of the

l-th genotype;

,

e

are the first-order interaction effects between the

i-th environment and

j-th density,

i-th environment and

l-th genotype, and

j-th density and

l-th genotype, respectively;

is the triple interaction effect between the

i-th environment,

j-th density and

l-th genotype;

is the random error associated with the plot, assumed ~ NID (0,

);

is the random error associated with the subplot, assumed ~ NID (0,

).

In the joint analysis, all effects were considered fixed, since the evaluation environments did not represent the entirety of the edaphoclimatic conditions of the North and Northwest Fluminense regions. The genotypes were treated as fixed because they consisted of selected materials, representing only the genotypes of interest, and the planting densities were also fixed because they were assigned specific values.

The evaluation of leaf greenness index (SPAD) was carried out only in the Campos dos Goytacazes—RJ environment. SPAD measurements were taken once per week over four weeks, based on the mean of the readings, and separated by plant population (plants ha

−1). In the individual analysis of variance, all effects were considered fixed, and the analysis was conducted according to the following statistical model:

where

is the observation in the

k-th replication, evaluated at the

i-th density and

j-th genotype;

is the overall mean of the experiment;

is the effect of the

k-th replication, assumed ~ NID (0,

);

is the fixed effect of the

i-th planting density;

is the fixed effect of the

j-th genotype;

is the first-order interaction effect between the

i-th planting density and the

j-th genotype;

is the random error associated with the plot, assumed ~ NID (0,

);

is the random error associated with the subplot, assumed ~ NID (0,

).

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Variance and Genetic Parameters

Table 1 presents the mean squares, genetic parameters, and descriptive statistics of evaluated traits, including estimates of genotypic variance (

), phenotypic variance (

), genotypic determination coefficient (

), and the experimental coefficient of variation

, based on the average values obtained in the Campos dos Goytacazes and Itaocara environments. There was a significant effect (

p < 0.01 or

p < 0.05) of genotypes for all evaluated traits, as well as a significant environment effect. Planting density showed a significant effect on ear length, ear diameter, and 100-grain weight. The interaction between environment and density was not significant for any trait, indicating that the effect of density was consistent across environments.

The interaction between environment and genotype was significant for ear length, ear diameter, 100-grain weight, and grain yield, demonstrating that genotype performance varied between environments. The interaction between density and genotype was significant only for ear diameter, while the triple interaction among environment, density, and genotype was not significant for any trait.

The overall mean grain yield was 4814.84 kg ha−1, considering both environments. The experimental coefficients of variation ranged from 3.62% (for ear diameter) to 24.36% (for grain yield), indicating good experimental precision. The genotypic determination coefficient ranged from 98.24% for plant height to 98.67% for ear height, suggesting that most of the observed phenotypic variation was of genetic origin. These results reinforce the existence of substantial genetic variability among the evaluated genotypes, which is essential for the success of breeding programs.

Given the significance of the interactions involving the environment factor, the results were presented and discussed separately for each environment (Campos dos Goytacazes and Itaocara) to allow a more precise interpretation of the effects of genotypes and planting densities on the evaluated traits. Mean comparisons were performed using Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05), considering the main effects of genotypes and densities within each environment.

3.2. Campos dos Goytacazes Environment

In this environment, no significant interaction between planting density and genotypes was observed, allowing the isolated analysis of the main effects of genotypes. For plant height, the hybrid UENF MS 2208 stood out with 2.58 m, with no significant differences among the other genotypes (

Figure 1a). Ear height ranged from 1.67 m (UENF MS 2208) to 0.96 m (BM 3061) (

Figure 1b).

For ear length, the highest value was observed in UENF 506-6 (16.24 cm) and the lowest in BR 106 (13.79 cm) (

Figure 1c). Ear diameter was highest in UENF 506-16 (44.31 mm), while BR 106 showed the lowest value (38.85 mm) (

Figure 1d).

Regarding 100-grain weight (GW100), UENF 506-16 stood out with 32.94 g, while AG 1051 had the lowest value (22.59 g) (

Figure 1e).

For grain yield (GY), UENF 506-16 achieved the highest mean in Campos (5384 kg ha

−1), followed by UENF MS 2208 (4325 kg ha

−1). The lowest values were observed in AG 1051 (2886 kg ha

−1) and BR 106 (2715 kg ha

−1) (

Figure 1f).

3.3. Itaocara Environment

As in Campos, no significant interaction between planting density and genotypes was observed, allowing the analysis of the main effects of genotypes.

For plant height, UENF MS 2208 showed the highest mean (2.77 m), while UENF 506-6 and BM 3061 recorded the lowest values (2.23 m and 2.22 m, respectively) (

Figure 2a). For ear height (EH), UENF MS 2208 again stood out (1.86 m), compared with BM 3061 (1.20 m) (

Figure 2b).

The highest ear length was observed in BM 3061 (18.34 cm), while the lowest value was recorded in UENF MSV 2210 (15.05 cm) (

Figure 2c). For ear diameter (ED), BM 3061 had the highest value (49.44 mm) and BR 106 the lowest (40.90 mm) (

Figure 2d).

Regarding 100-grain weight (GW100), UENF MS 2208 presented the highest value (34.34 g), and BR 106 the lowest (28.79 g) (

Figure 2e). For grain yield (GY), BM 3061 led with 7118 kg ha

−1, followed by UENF 506-16 (6855 kg ha

−1), with no significant difference between them. BR 106 showed the lowest value (4316 kg ha

−1) (

Figure 2f).

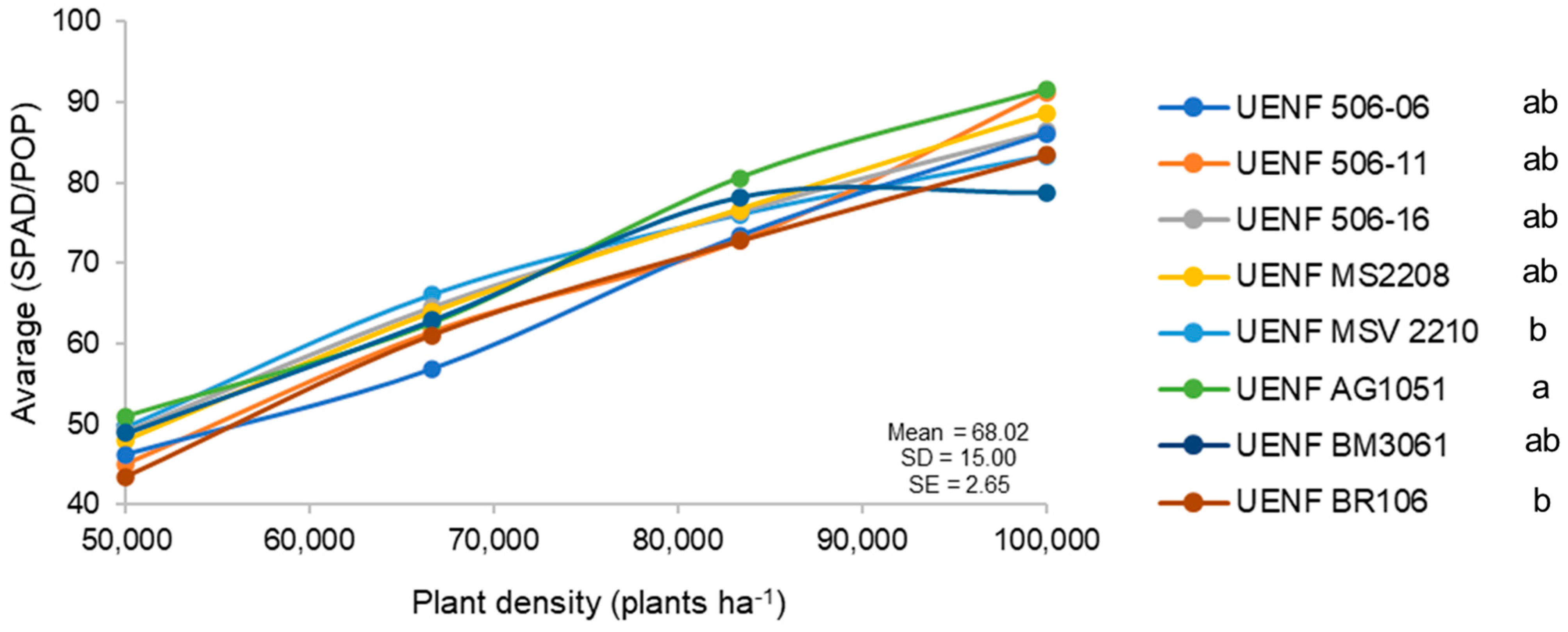

3.4. Greenness Index (SPAD)

The SPAD variable was evaluated exclusively in the Campos dos Goytacazes environment and is expressed as SPAD/POP, which considers the greenness index in relation to planting density.

Analysis of variance showed a significant effect (

p < 0.01) of both density and genotypes, with no significant interaction between these factors. The overall mean was 45.77, with a genotypic determination coefficient of 71% and a coefficient of variation of 5.95%. The hybrid UENF 506-16 had the highest SPAD/POP value (115.81), while AG 1051 showed the lowest (60.29) (

Table 2 and

Figure 3).

Higher planting densities were associated with increased SPAD/POP values, suggesting greater leaf greenness under denser stands. Although the SPAD index was measured in only one environment, a positive tendency between SPAD/POP and grain yield was observed, indicating that genotypes maintaining higher chlorophyll content under competition may better sustain productivity. However, this relationship should be interpreted with caution and limited to the evaluated environment, as SPAD represents an indicative, not conclusive, measure of physiological performance.

Mean data of other morphological traits (

Table 3) showed that increasing planting density tended to reduce ear length, ear diameter, and 100-grain weight, consistent with greater competition for resources under higher plant populations.

3.5. Effect of Plant Population Density on Grain Yield and Regression Analysis

The combined analysis of variance (

Table 1) indicated no significant interaction between density and genotypes for grain yield, which allowed the isolated effect of plant density on this trait to be evaluated.

In general, the density of 100,000 plants ha−1 showed the highest mean grain yield (5037 kg ha−1), differing significantly only from the lowest density (50,000 plants ha−1), which presented the lowest mean (4234 kg ha−1). The other densities (66,667 and 83,333 plants ha−1) did not differ statistically from the highest density, although they exhibited slightly lower yields (4972 and 5017 kg ha−1, respectively).

Grain yield fitted a quadratic regression model as a function of plant population density, with a coefficient of determination (R2 = 95%; y = −6 × 10−7x2 + 0.116x + 300.5), showing an optimal density point close to 100,000 plants ha−1. This behavior suggests that increasing plant density enhances yield up to a certain threshold, beyond which intraspecific competition may compromise performance.

3.6. Effect of Plant Density on Grain Yield Across Genotypes

No significant interaction between plant population density and genotypes for grain yield was detected, allowing the effect of density to be evaluated across all hybrids. Grain yield tended to increase with higher plant density, with the highest mean observed at 100,000 plants ha

−1 (5037 kg ha

−1). However, according to Tukey’s test, the three highest densities (66,667, 83,333, and 100,000 plants ha

−1) were not statistically different (

Table 3), indicating that yield gains reached a plateau above approximately 66,000 plants ha

−1 under the studied conditions.

Numerical differences among genotypes were observed across densities (

Table 4). For example, in Campos dos Goytacazes, UENF 506-16 achieved the highest yield (5384 kg ha

−1), followed by UENF MS 2208 (4324 kg ha

−1), while in Itaocara, BM 3061 (7118 kg ha

−1) and UENF 506-16 (6855 kg ha

−1) showed the highest values. At specific densities, slight trends were noted: UENF 506-16 reached 6483 kg ha

−1 at 66,667 plants ha

−1, BM 3061 reached 5809 kg ha

−1 at 83,333 plants ha

−1, and UENF 506-11 reached 5789 kg ha

−1 at 100,000 plants ha

−1.

These observations represent numerical tendencies rather than statistically significant genotype × density interactions. Therefore, interpretations should focus on the general effect of plant density on grain yield, which increased with higher densities, rather than on genotype-specific preferences.

3.7. Economic Value of Grain Yield

Table 5 presents the estimated economic advantage per hectare for the genotypes BR 106, AG 1051, and UENF 506-11, calculated based on the mean grain yield obtained for each planting density, considering a price of R

$ 40.00 per 60 kg bag of maize and, seed costs of R

$ 140.00, R

$ 270.00, and R

$ 150.00 per 10 kg bag, respectively.

The hybrid UENF 506-11 showed the highest economic return among the registered materials, with an estimated R$ 3409.33 ha−1 at a density of 100,000 plants ha−1, where it also achieved the highest grain yield (5789 kg ha−1).

For the hybrid UENF 506-16, not yet registered, a density of 66,667 plants ha−1 resulted in the highest grain yield (6483 kg ha−1) and the best estimated economic advantage, reaching R$ 4022.00 ha−1, considering the same seed cost as UENF 506-11.

The density of 50,000 plants ha−1 resulted in the lowest grain yield (4234 kg ha−1) and, consequently, the lowest estimated revenue (R$ 2896.00 ha−1), even with the lowest seed cost.

4. Discussion

The absence of significant interaction between plant density and genotype for most traits indicates that the hybrids presented consistent agronomic responses across the spatial arrangements tested. This stability is desirable in breeding programs aimed at identifying materials with predictable performance under varying management conditions. Similar results were reported by Kappes et al. [

27] for maize hybrids. In contrast, Scheeren et al. [

28] observed a significant increase in plant height at higher densities, which can be attributed to light competition and hormonal regulation. This response is consistent with the mechanism described by Wang et al. [

29], in which light-induced remodeling of phytochrome B triggers auxin-mediated elongation as part of the plant’s shade-avoidance response. These differences highlight that morphological responses to plant density may depend on genotype architecture and environmental factors. Recent studies, such as those by Longo et al. [

30] and Ruswandi et al. [

31], have further emphasized that genotype-specific architecture and plasticity play key roles in maize adaptability to higher plant populations.

For ear length and diameter, the decreasing trend observed with increasing density agrees with Brachtvogel et al. [

32] and Dourado Neto et al. [

33], who associated this reduction with competition for light, water, and nutrients. While narrower spacing can optimize resource capture, excessive crowding may limit assimilate partitioning to reproductive organs. Similar trade-offs were reported in green maize by Arruda et al. [

18] and in conventional hybrids by Bassu et al. [

9], reinforcing that the balance between plant number and individual ear development determines yield efficiency. Comparable reductions in ear traits under denser planting have also been described by Du et al. [

34] who demonstrated that microclimatic changes and limited radiation penetration within the canopy affect the balance between vegetative growth and reproductive allocation.

The decline in 100-grain weight with increasing plant density corroborates results by Strieder et al. [

35] and Li et al. [

8], who attributed this pattern to reduced assimilate availability per kernel and shortened grain filling duration under high competition. This demonstrates that while denser canopies increase total leaf area index, they can also restrict the photosynthate supply to each ear. Optimizing density, therefore, requires balancing light interception efficiency with the maintenance of individual grain weight.

Despite these component reductions, grain yield per area increased with higher plant density, reaching 5.04 t ha

−1 at 100,000 plants ha

−1. This increase reflects the compensation between per-plant productivity and plant number, a response commonly observed in maize (Demétrio et al. [

16]; Modolo et al. [

36]; Kappes et al. [

27]). Similar behavior was reported by Shao et al. [

5] in a global meta-analysis, which found an average yield increase of 11.2% under higher densities due to improved radiation interception and dry matter remobilization. Maize grain yield also increases with plant density up to an optimal threshold, although the magnitude of the response varies among hybrids and environmental conditions, as observed by Mandić et al. [

6] and Sol et al. [

37]. Gao et al. [

14] further confirmed that this positive effect occurs in different environments, suggesting a general physiological mechanism rather than a location-specific response. The regression models fitted for each hybrid further support this pattern, with linear or quadratic relationships between yield and density. Differences among hybrids likely reflect variation in plant architecture and resource allocation strategies, influencing their adaptability to crowding. Ruswandi et al. [

31] also highlighted that multi-trait selection under single and intercropping systems can enhance hybrid performance and stability, aligning with the current findings.

For instance, UENF 506-16 maintained high yield at intermediate density (66,667 plants ha−1), while UENF MS 2208 and BM 3061 performed best at the highest density. These responses suggest differential tolerance to competition and indicate potential suitability for higher-density cultivation under similar edaphoclimatic conditions. However, broader recommendations should await confirmation through multi-environment and multi-year evaluations.

The economic analysis aligned with the agronomic results, showing that moderate to high densities increased net returns. UENF 506-16 presented the highest estimated economic advantage (BRL 4022.00 ha−1 at 66,667 plants ha−1), combining productivity with cost efficiency, while UENF 506-11 stood out among the commercial checks at 100,000 plants ha−1 (5.79 t ha−1 and BRL 3409.33 ha−1). These results demonstrate that controlled density management can enhance profitability, although the conclusions are specific to the studied conditions.

Overall, the findings indicate that the optimal plant density depends on each hybrid’s morphophysiological response and its capacity to maintain yield components under competition. The evaluated hybrids, particularly UENF 506-16, showed promising performance under higher densities, but further multi-environment testing is required before practical recommendations for intensive production systems can be made.

We acknowledge that the main limitation of this study is the use of data from a single growing season and a limited number of hybrids. Although the two contrasting locations partially compensate for this limitation, future research should include multi-season trials and a broader set of genotypes to increase the robustness of the conclusions. These additional experiments will help validate the stability of hybrid performance under different climatic conditions and planting densities.

5. Conclusions

Increasing plant density proved to be an effective strategy to enhance maize grain yield in both evaluated regions, although it reduced some morphological traits such as plant and ear height. The magnitude of yield gains, however, varied slightly between the North (Campos dos Goytacazes) and Northwest (Itaocara) regions, indicating that local edaphoclimatic conditions influence hybrid responses to competition. Higher densities were generally more favorable for hybrids with greater vigor and tolerance to crowding stress, especially UENF 506-16 and UENF 506-11, which maintained superior grain yield and economic return even under intensified planting.

In contrast, hybrids with less competitive architecture showed reduced yield stability at the highest densities, reinforcing the need for genotype-specific recommendations. Overall, our findings indicate that the optimal plant density depends on each hybrid’s morphophysiological response and its ability to sustain yield components under competition. Adjusting plant density according to hybrid characteristics and local production conditions is therefore essential to maximize productivity and profitability in the North and Northwest regions of Rio de Janeiro.

Future studies should include multi-season trials and a broader set of genotypes to confirm the stability of these responses under different climatic scenarios and strengthen regional recommendations.