Passive Occupant Safety Solutions for Non-Conventional Seating Positions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

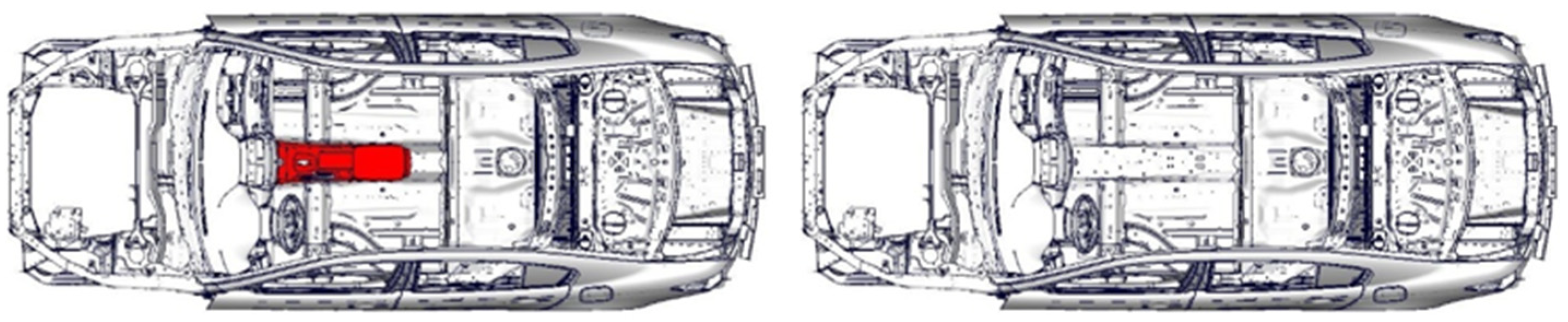

2.1. Advanced Simulation Model

2.2. Validation of the Simulations

2.3. Passive Safety Solutions for Non-Conventional Seating Positions

3. Results and Discussion

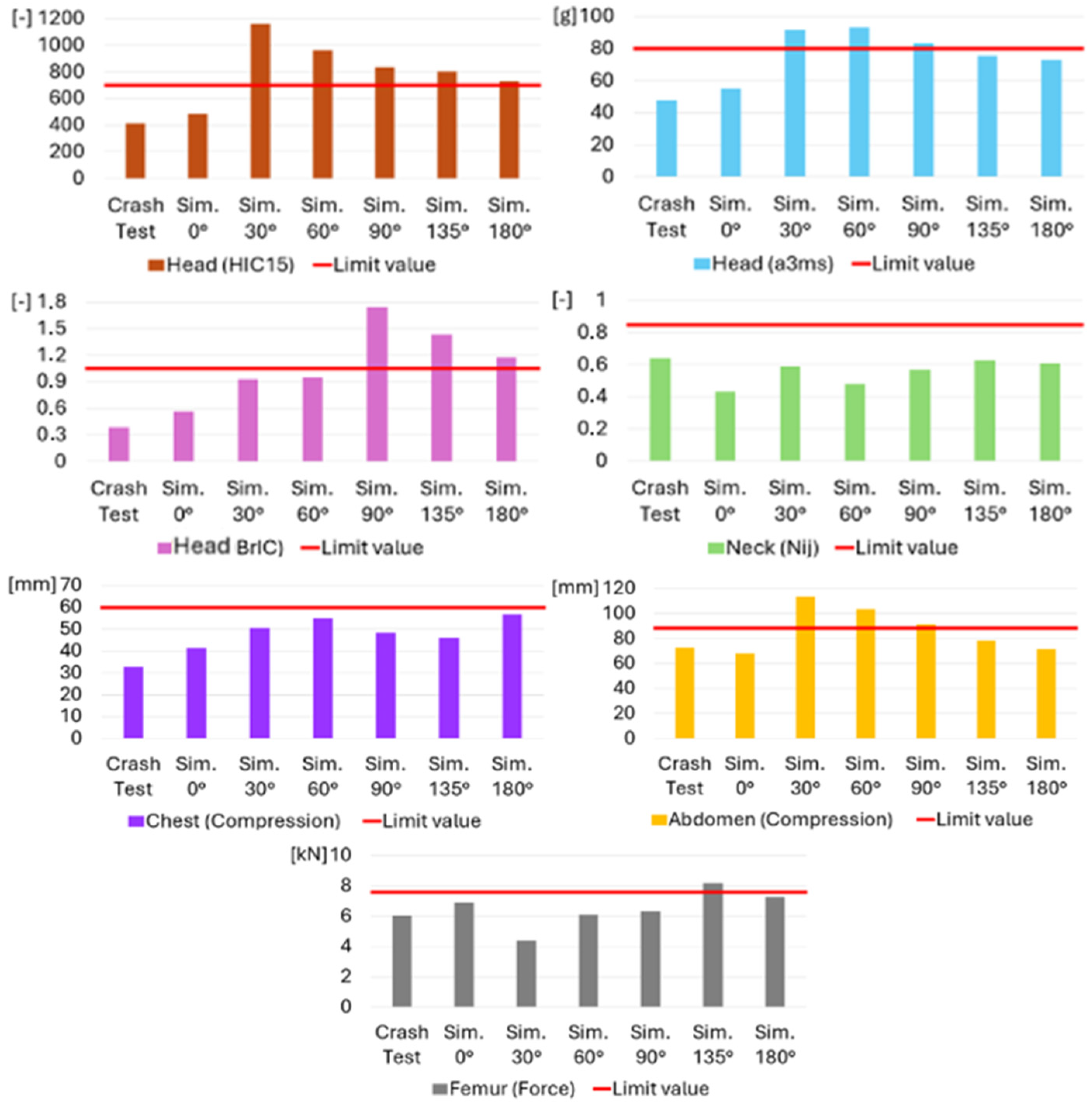

3.1. Results Obtained with Rotated Seating Positions

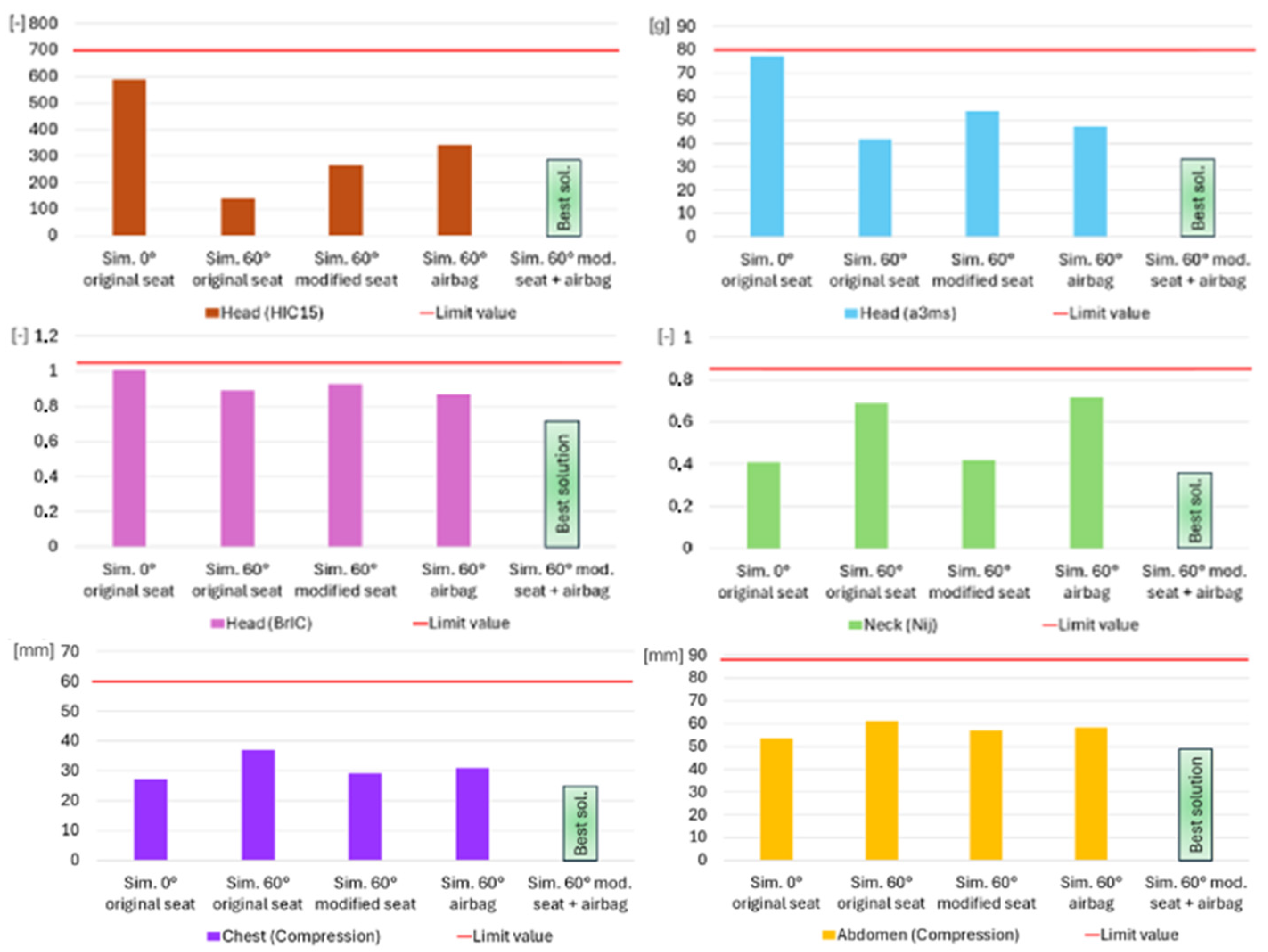

3.2. Results Obtained with the Modified Seat and Airbag Concept

3.3. Results Obtained When Using the Modified Seat and Airbag Concept Together

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pettersson, I.; Karlsson, M. Setting the stage for autonomous cars: A pilot study of future autonomous driving experiences. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2015, 9, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.T.Z.; Shi, M.G. Nonlinear multibody dynamics and finite element modeling of occupant response. Int. J. Mechan. Mater. Des. 2019, 15, 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, B.; Gan, S.; Chen, W.; Zhou, Q. Seating preferences in highly automated vehicles and occupant safety awareness: A national survey of Chinese perceptions. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2020, 21, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, J.; Jesus, R.; Katarina, B. Seating preferences in highly automated vehicles are dependent on yearly exposure to traffic and previous crash experiences. In Proceedings of the IRCOBI Conference, Florence, Italy, 11–13 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Koppel, S.; Jiménez Octavio, J.; Bohman, K.; Logan, D.; Raphael, W.; Quintana Jimenez, L.; Lopez-Valdes, F. Seating configuration and position preferences in fully automated vehicles. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2019, 20, S103–S109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, Y.; Hayashi, S.; Yamada, K.; Gotoh, M. Occupant Kinematics in Simulated Autonomous Driving Vehicle Collisions: Influence of Seating Position, Direction and Angle; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jorlov, S.; Bohman, K.; Larsson, A. Seating positions and activities in highly automated cars, a qualitative study of future automated driving scenarios. In Proceedings of the IRCOBI Conference, Antwerp, Belgium, 13–15 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Górniak, A.; Matla, J.; Górniak, W.; Magdziak-Tokłowicz, M.; Krakowian, K.; Zawiślak, M.; Włostowski, R.; Cebula, J. Influence of a passenger position seating on recline seat on a head injury during a frontal crash. Sensors 2022, 22, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.; Müller, G.; Müller, S. The effect of a braking maneuver on the occupant’s kinematics of a highly reclined seating position in a frontal crash. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2023, 24, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, C.E.; Ghajari, M. How do demographic factors, non-standard and out-of-position seating affect vehicle occupant injury outcomes in road traffic collisions? Saf. Sci. 2025, 187, 106834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Samad, M.S.; Mohd Nor, M.K.; Abdul Majid, M.M.; Abu Kassim, K.K. Optimization of vehicle pulse index parameters based on validated vehicle-occupant finite element model. Int. J. Crashworthiness 2022, 28, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, K.; Xu, R.; Jung, S.; Sobanj, J. Development and testing of a simplifed dummy for frontal crash. Exp. Tech. 2019, 43, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurano, Y.; Hikida, K.; Hibara, S.; Kawamura, Y.; Maehara, K.; Narukawa, T. Two-dimensional degenerated model of next-generation crash test dummy thor 5f. Int. J. Automot. Eng. 2020, 11, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Song, K.; Hong, S. Estimation of Whole-Body Injury Metrics for Evaluating Effect of Airbag Deployment. Automot. Technol. Springer 2023, 24, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umale, S.; Arun, M.; Hauschild, H. Quantitative evaluation of THOR world SID and hybrid III under farside impacts. In Proceedings of the International Research Council on the Biomechanics of Injury, Athens, Greece, 12–14 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L.; Zheng, J.; Hu, J. A numerical investigation of factors affecting lumbar spine injuries in frontal crashes. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2020, 136, 105400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porkolab, L.; Lakatos, I. Possibilities for further development of the driver’s seat in the case of a non-conventional seating positions. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porkolab, L.; Lakatos, I. Possibilities for Further Development of the Airbags in the Case of Non-conventional Seating Positions. Period. Polytech. Transp. Eng. 2025, 53, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Appel, H. The influence of different airbag folding patterns on the potential dangers of airbags. ATZ Worldwide 2002, 104, 26–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samantray, S.; Parashar, S. Airbag used in automobile. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 81, 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myeongkwan, K.; Hyungjoo, K. Occupant safety effectiveness of proactive safety seat in autonomous emergency braking. Sci. Rep. Springer 2022, 12, 5727. [Google Scholar]

- Bohman, K.; Ortlund, R.; Growth, G.K.; Nurbo, P.; Jakobsson, L. Evaluation of users’ experience and posture in a rotated swivel seating configuration. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2020, 21, S13–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marin, M.D.; Alonso, J.A. Child safety in autonomous vehicles: Living room layout. Dyna Ing. E Ind. 2022, 97, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Diederich, A.; Bastien, C.; Ekambaram, K.; Wilson, A. Occupant pre-crash kinematics in rotated seat arrangements. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D-J. Automob. Eng. 2021, 235, 2818–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Gao, R.; McCoy, R.; Hu, H.; He, L.; Gao, Z. Effects of an integrated safety system for swivel seat arrangements in frontal crash. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1153265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Hou, H.; Shen, M. Occupant kinematics and biomechanics during side collision in autonomous vehicles can rotatable seat provides additional protection. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 23, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Criteria | Unit | Limit Value | Crash Test | Simulation 0° Base Model Without any Modifications | Simulation 0° Fitted Model with All Modifications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head (HIC15) | [-] | 700 | 416 | 437 (+5%) | 487 (+17%) |

| Head (a3ms) | [g] | 80 | 47.4 | 49.4 (+4%) | 55.1 (+16%) |

| Head (BrIC) | [-] | 1.05 | 0.39 | 0.42 (+8%) | 0.57 (+46%) |

| Neck (Nij) | [-] | 0.85 | 0.64 | 0.63 (−2%) | 0.43 (−32%) |

| Chest (Compression) | [mm] | 60 | 32.8 | 34.3 (+5%) | 41.4 (+26%) |

| Abdomen (Compression) | [mm] | 88 | 72.9 | 70.7 (−3%) | 68.1 (−7%) |

| Femur (Force) | [kN] | 7.56 | 6.03 | 6.25 (+4%) | 6.88 (+14%) |

| Criteria | Unit | Limit Value | Crash Test | Simulation 0° Base Model Without any Modifications | Simulation 0° Fitted Model with All Modifications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head (HIC15) | [-] | 700 | 541 | 575 (+6%) | 592 (+9%) |

| Head (a3ms) | [g] | 80 | 71.4 | 72.9 (+2%) | 77.6 (+8%) |

| Head (BrIC) | [-] | 1.05 | 0.86 | 0.93 (+8%) | 1.01 (+17%) |

| Head (Nij) | [-] | 0.85 | 0.62 | 0.44 (−29%) | 0.41 (−34%) |

| Chest (Compression) | [mm] | 60 | 25.8 | 27.0(+5%) | 27.4 (+6%) |

| Abdomen (Compression) | [mm] | 88 | 58.9 | 55.2 (−6%) | 53.7 (−9%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Porkolab, L.; Lakatos, I. Passive Occupant Safety Solutions for Non-Conventional Seating Positions. Future Transp. 2026, 6, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp6010007

Porkolab L, Lakatos I. Passive Occupant Safety Solutions for Non-Conventional Seating Positions. Future Transportation. 2026; 6(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp6010007

Chicago/Turabian StylePorkolab, Laszlo, and Istvan Lakatos. 2026. "Passive Occupant Safety Solutions for Non-Conventional Seating Positions" Future Transportation 6, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp6010007

APA StylePorkolab, L., & Lakatos, I. (2026). Passive Occupant Safety Solutions for Non-Conventional Seating Positions. Future Transportation, 6(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp6010007