Effectiveness of Variable Message Signs on Utah Roadways

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

3.1. Diversion Rate Analysis

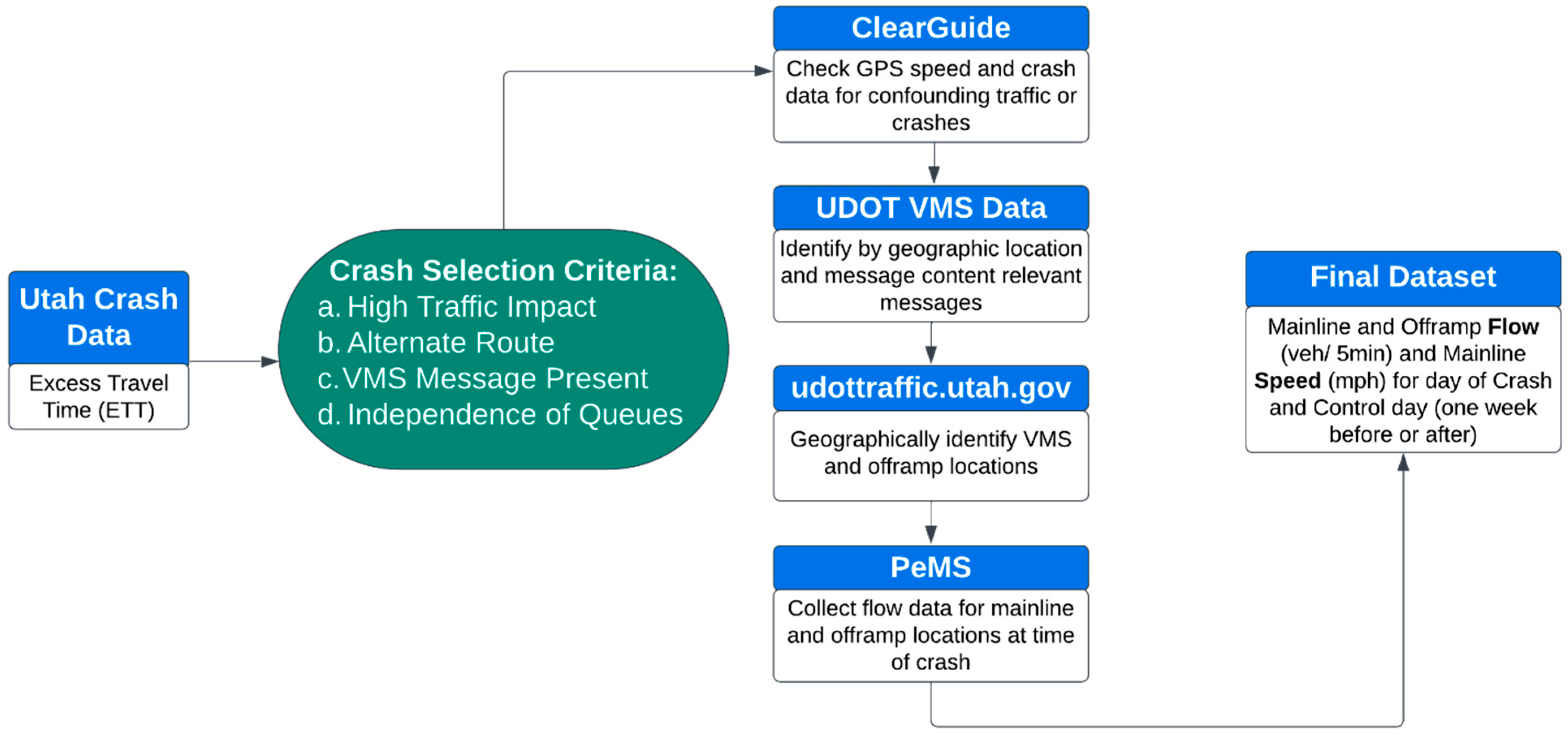

3.1.1. Diversion Rate Analysis Data

- The crash needed to have a high ETT. A higher ETT was theorized to correlate with a larger number of drivers impacted, longer queues, a higher potential for drivers to divert, and more freeway offramps available for analysis. While a high ETT threshold was not quantified, crashes were sorted by ETT and those with the highest ETT were evaluated first.

- At least one alternate route for drivers to bypass the crash was required. Alternate routes around the crash were critical so vehicles had an incentive to exit the roadway.

- The posting of at least one VMS message upstream of the crash pertaining to the crash was required.

- Crash queues needed to be independent from other congestion or crashes on the freeway. This was important for reducing the effect of confounding variables on the crash queues and to increase the probability that any increase in vehicles diverting were due to the incident being studied.

3.1.2. Diversion Rate Analysis Methodology

3.2. Weather Analysis

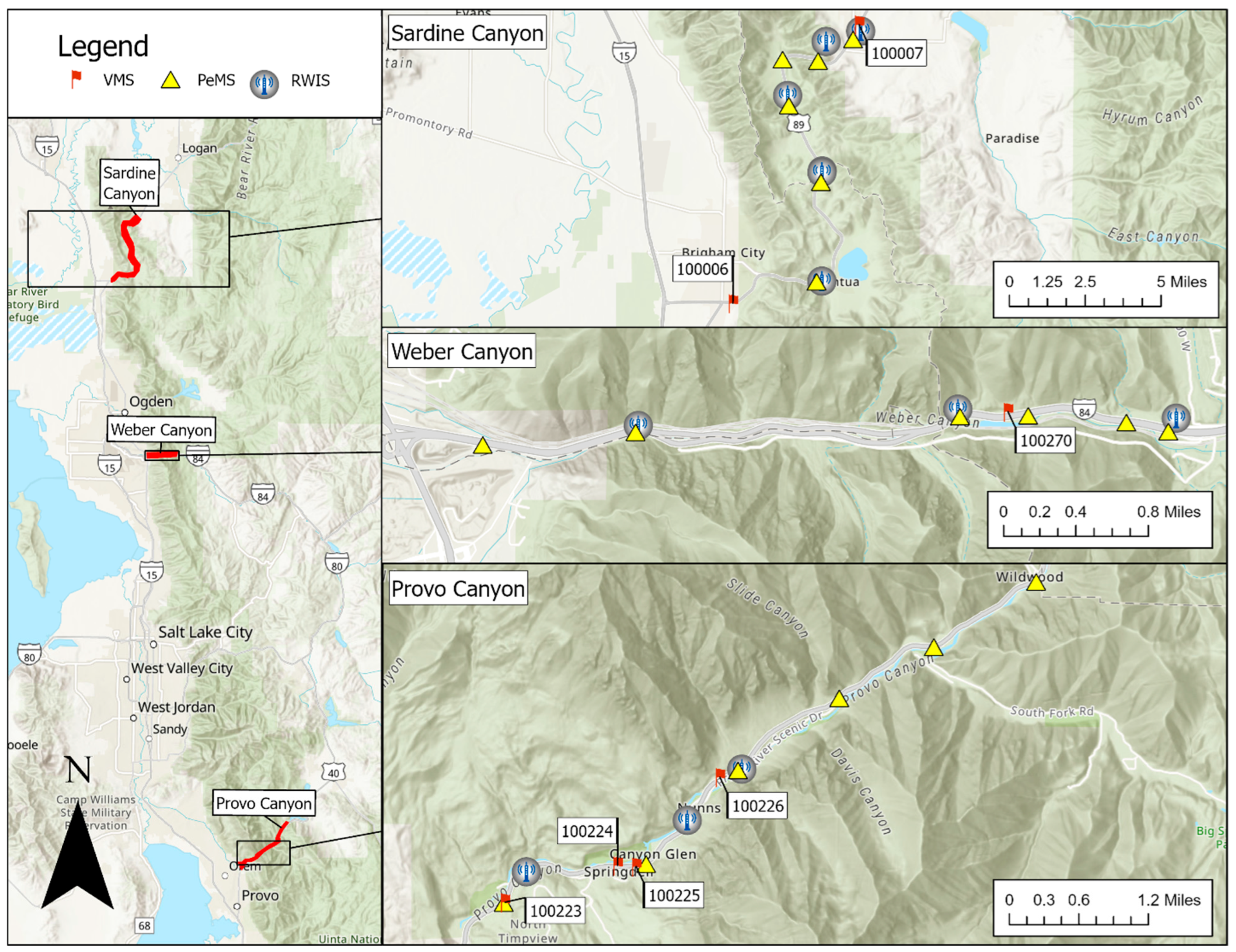

3.2.1. Weather Analysis Data

3.2.2. Weather Analysis Methodology

4. Results

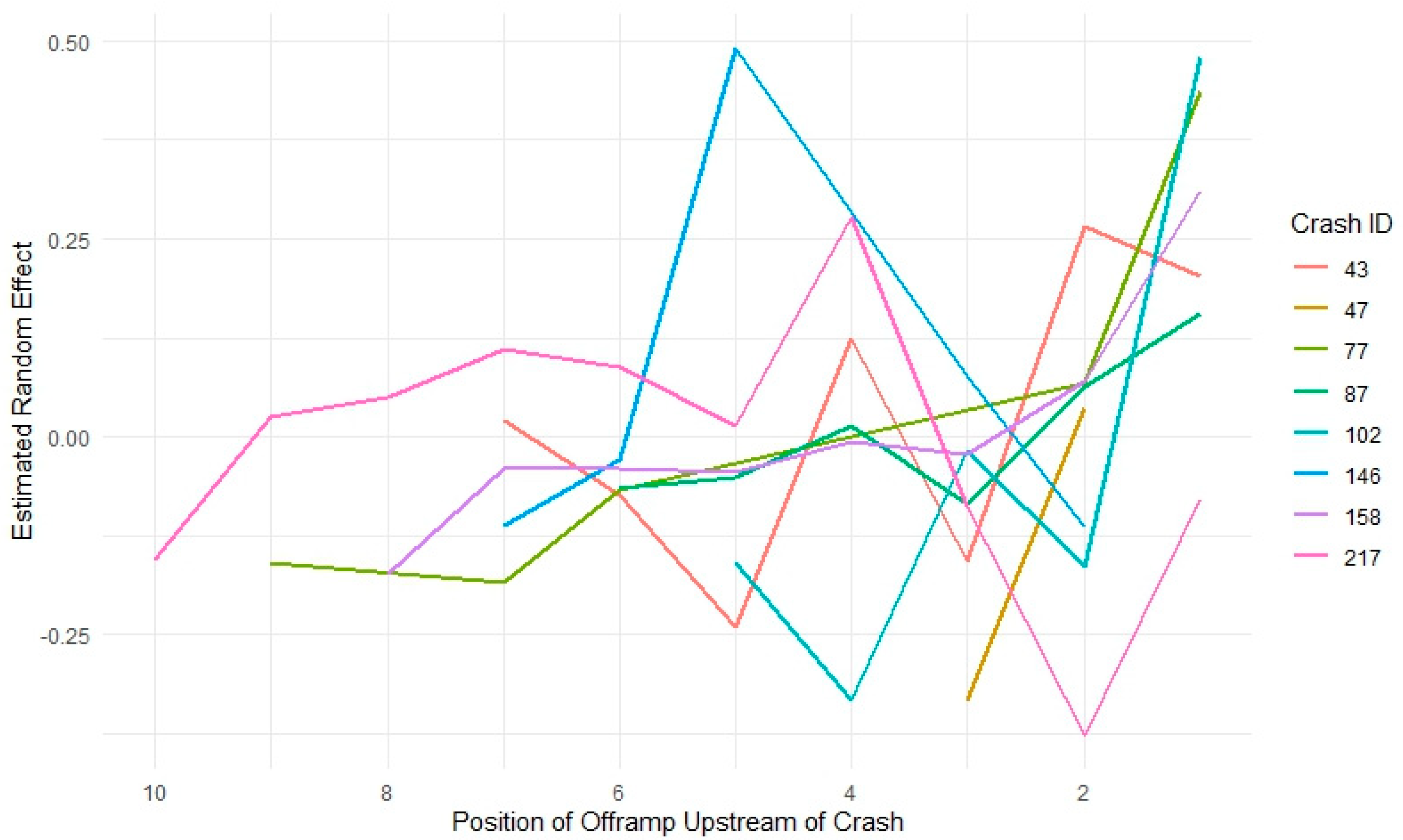

4.1. Diversion Rate Analysis Results

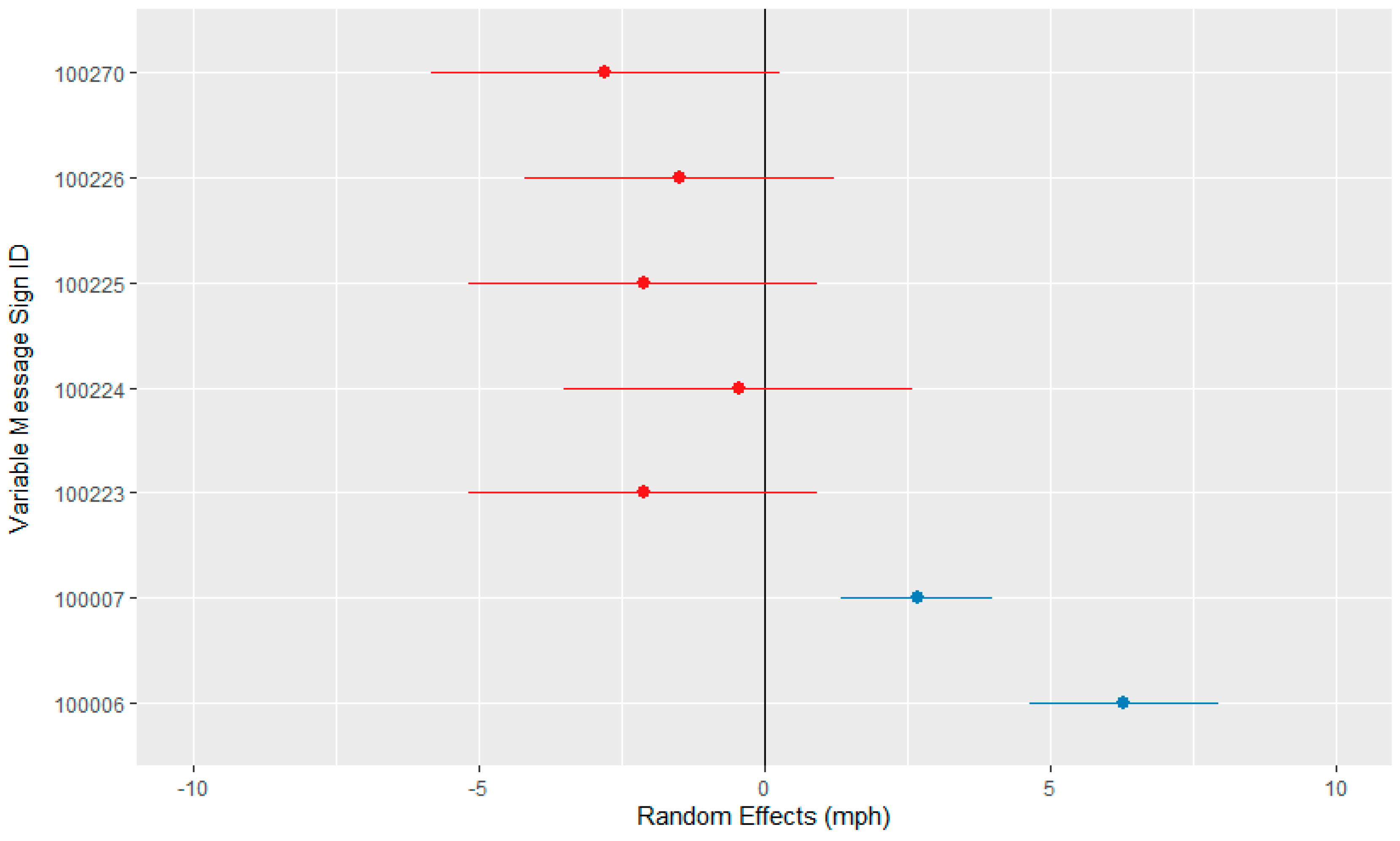

4.2. Weather Analysis Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DOTs | Departments of transportation |

| ETT | Excess Travel Time |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| PeMS | Performance Measurement System |

| PHF | Peak Hour Flow |

| RWIS | Road Weather Information System |

| UDOT | Utah Department of Transportation |

| VMS | Variable message sign(s) |

References

- Tay, R.; de Barros, A.G. Public Perceptions of the Use of Dynamic Message Signs. J. Adv. Transp. 2008, 42, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, N.; Rong, J. Effectiveness, Influence Mechanism and Optimization Strategies of Variable Message Sign: A Systematic Review. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2024, 105, 116–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardman, M.; Bonsall, P.W.; Shires, J.D. Driver response to variable message signs: A stated preference investigation. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 1997, 5, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, K.; Hounsell, N.B.; Firmin, P.E.; Bonsall, P.W. Driver Response to Variable Message Sign Information in London. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2002, 10, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, K.; Mcdonald, M. Effectiveness of Using Variable Message Signs to Disseminate Dynamic Traffic Information: Evidence from Field Trails in European Cities. Transp. Rev. 2004, 24, 559–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusakabe, T.; Sharyo, T.; Asakura, Y. Effects of Traffic Incident Information on Drivers’ Route Choice Behaviour in Urban Expressway Network. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 54, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Zhou, L.; Ma, S.; Jia, N. Effects of Different Factors on Drivers’ Guidance Compliance Behaviors under Road Condition Information Shown on VMS. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2012, 46, 1490–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Choi, J.; Jeong, S.; Tay, R. Effects of Variable Message Sign on Driver Detours and Identification of Influencing Factors. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2014, 8, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Luo, M.; Chien, S.I.-L.; Hu, D.; Zhao, X. Analysing Drivers’ Perceived Service Quality of Variable Message Signs (VMS). PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Wang, H. Effects of Urban Road Variable Message Signs on Driving Behavior. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2019, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwende, S.; Kwigizile, V.; Lyimo, S.; Van Houten, R.; Oh, J. Impact of the Proliferation of Smart Devices on the Usefulness of Changeable Message Signs (CMS). Adv. Transp. Stud. 2024, 63, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, W.H.K.; Chan, K.S. A Model for Assessing the Effects of Dynamic Travel Time Information via Variable Message Signs. Transportation 2001, 28, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, D.; Huo, H. Effectiveness of Variable Message Signs Using Empirical Loop Detector Data. In Proceedings of the 85th Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board, Washington, DC, USA, 22–26 January 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Erke, A.; Sagberg, F.; Hagman, R. Effects of Route Guidance Variable Message Signs (VMS) on Driver Behaviour. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2007, 10, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, B.; Zhu, Y.; Dauwels, J. Effectiveness of VMS Messages in Influencing the Motorists’ Travel Behaviour. In Proceedings of the 2018 21st International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 November 2018; pp. 837–842. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, F.; Gomez, J.; Rangel, T.; Jurado-Piña, R.; Vassallo, J.M. The Influence of Variable Message Signs on En-Route Diversion between a Toll Highway and a Free Competing Alternative. Transportation 2020, 47, 1665–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, F.; Cifuentes, A.; Pezoa, R.; Varas, M. A Vehicle-by-Vehicle Approach to Assess the Impact of Variable Message Signs on Driving Behavior. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 125, 103015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, Y.; Kanafani, A. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Accident Information on Freeway Changeable Message Signs: A Comparison of Empirical Methodologies. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2014, 48, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glendon, A.I.; Lewis, I. Field Testing Anti-Speeding Messages. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2022, 91, 431–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rämä, P.; Kulmala, R. Effects of Variable Message Signs for Slippery Road Conditions on Driving Speed and Headways. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2000, 3, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshari, S.; Pahari, S.; Cavka, M.; Bahrami, V.; Racine, J.; Gates, T.J.; Savolainen, P.T. Driver Response to Winter Weather Warning Messages on Changeable Message Signs Approaching Freeway Bridge Overpasses. Transp. Res. Rec. 2025, 03611981251387132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Y.; Young, R. Impact of Dynamic Message Signs on Speeds Observed on a Rural Interstate. J. Transp. Eng. 2014, 140, 04014020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, G.G.; Hyer, J.C.; Holdsworth, W.H.; Eggett, D.L.; Macfarlane, G.S. Analysis of Benefits of UDOT’s Expanded Incident Management Team Program; Report No. UT-23.05; Utah Department of Transportation, Research & Innovation: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2023.

- Traffic Division; Utah Department of Transportation. UDOT Traffic Dashboard. 2023. Available online: https://udottraffic.utah.gov (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Kronmal, R.A. Spurious Correlation and the Fallacy of the Ratio Standard Revisited. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Stat. Soc. 1993, 156, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, G.G.; Davis, M.C.; Hill, A.; Snow, G.L. Effectiveness of ITS on Utah Roadways; Report UT-23.20; Utah Department of Transportation, Research & Innovation: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2023.

- Department of Atmospheric Sciences, University of Utah. MesoWest Dashboard. 2023. Available online: https://mesowest.utah.edu/ (accessed on 24 December 2005).

- Traffic Division, Utah Department of Transportation. Freeway Performance Metrics, Occurrence Data. 2023. Available online: https://www.udottraffic.utah.gov/FPM/VehicleEvent/EventReport (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Han, J.; Kamber, M.; Pei, J. Data Mining: Concepts and Techniques, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Waltham, MA, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-12-381480-7. [Google Scholar]

| Author(s) | Site Location | Type of Study | Effect of VMS Messaging |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lam and Chan; 2001 [12] | Hong Kong | With-and-Without | Reduction in travel time delay during crash or work zone congestion |

| Levinson and Huo; 2006 [13] | MN, USA | With-and-Without | No clear reduction in travel times, but VMS and ramp meters reduced total delay up to 136 vehicle-hours per peak period incident |

| Erke et al.; 2007 [14] | Oslo, Norway | With-and-Without | Reported 20 percent of vehicles diverted based on the provided route recommendation |

| Ghosh et al.; 2018 [15] | Singapore | Before-and-After | Increased diversions by 14 percent |

| Romero et al.; 2020 [16] | Spain | With-and-Without | Increased diversions onto tolled highway |

| Basso et al.; 2021 [17] | Chile | Before-and-After | No significant influence on driver behavior (speed, lane change, traffic volume) |

| Xuan and Kanafani; 2014 [18] | CA, USA | Before-and-After | No significant effect on diversions |

| Glendon and Lewis; 2022 [19] | Australia | Before-and-After | Reduction in speeds; effect varied by time of day and day of week |

| Rämä and Kulmala; 2000 [20] | Finland | Before-and-After | Reduction in speeds by 0.75 mph (1.2 kph) |

| Keshari et al.; 2025 [21] | MI, USA | Before-and-After | “Slippery Road Conditions/Reduce Speeds” message reduced speeds by 0.6–0.7 mph |

| Sui and Young; 2014 [22] | WY, USA | With-and-Without | VMS speed reductions range from 5 mph to 20 mph above reductions caused by weather |

| Diversion Rates Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | CI | p |

| (Intercept) | 0.78 | 0.58–0.97 | <0.001 |

| RCD | 0.03 | 0.02–0.04 | <0.001 |

| VMS | 0.18 | 0.12–0.24 | <0.001 |

| SRadj | −0.78 | −0.99–−0.58 | <0.001 |

| VMS × SRadj | −0.50 | −0.72–−0.29 | <0.001 |

| Random Effects | |||

| σ2 | 0.13 | ||

| τ00 Crash:Mramp | 0.04 | ||

| τ00 Crash | 0.05 | ||

| ICC | 0.42 | ||

| NCrash | 8 | ||

| NMramp | 31 | ||

| Observations | 624 | ||

| Marginal R2/Conditional R2 | 0.455/0.681 | ||

| Weather Speed Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | CI | p |

| (Intercept) | 28.942 | 26.07–31.82 | <0.001 |

| SignPhase [On] | 0.228 | 0.17–0.29 | <0.001 |

| TimeState [AM] | −0.311 | −0.37–−0.26 | <0.001 |

| TimeState [PM] | −2.393 | −2.42–−2.36 | <0.001 |

| MilePost Diff | 0.015 | 0.01–0.02 | <0.001 |

| PHF (per 0.2) | 0.502 | 0.47–0.54 | <0.001 |

| Hourly Flow (per 500 vph) | 2.894 | 2.85–2.94 | <0.001 |

| Road grip (per 0.1) | 3.344 | 3.32–3.37 | <0.001 |

| Visibility [Light Precip] | −1.613 | −1.65–−1.57 | <0.001 |

| Visibility [Mod. Precip] | −2.669 | −2.74–−2.6 | <0.001 |

| Visibility [Heavy Precip] | −5.104 | −5.2–−5.01 | <0.001 |

| Random Effects | |||

| σ2 | 81.4 | ||

| τ00 MessageNum:VMS.ID | 8.97 | ||

| τ00 VMS.ID | 12.84 | ||

| ICC | 0.21 | ||

| NMessageNum | 47 | ||

| NVMS.ID | 7 | ||

| Observations | 1,426,105 | ||

| Marginal R2/Conditional R2 | 0.190/0.361 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Davis, M.C.; Hill, A.W.; Schultz, G.G.; Snow, G.L. Effectiveness of Variable Message Signs on Utah Roadways. Future Transp. 2026, 6, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp6010004

Davis MC, Hill AW, Schultz GG, Snow GL. Effectiveness of Variable Message Signs on Utah Roadways. Future Transportation. 2026; 6(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp6010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleDavis, Matthew C., Adam W. Hill, Grant G. Schultz, and Gregory L. Snow. 2026. "Effectiveness of Variable Message Signs on Utah Roadways" Future Transportation 6, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp6010004

APA StyleDavis, M. C., Hill, A. W., Schultz, G. G., & Snow, G. L. (2026). Effectiveness of Variable Message Signs on Utah Roadways. Future Transportation, 6(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp6010004