1. Introduction

Many settlements have set themselves the objective of increasing the use of public transport, i.e., to attract a proportion of car passengers to public transport in order to reduce environmental impacts [

1]. A common obstacle is that potential passengers are not familiar with the public transport offer: neither the travel conditions nor the fares, much less the network and timetable, and are not willing to invest serious effort in learning more about them. In addition to the objective characteristics of the service (e.g., fares, frequency, comfort, cleanliness, public and transport safety, etc.), this lack of information also creates a psychological barrier that makes it difficult to expand the passenger base [

2].

What makes the public transport network transparent, i.e., easy to understand, and what leads to the opposite? It is a natural correlation that as the served area increases in size and complexity (after a certain level), the size and complication of the network necessarily increase, but there are many examples of smaller settlements having a relatively more complex network than larger cities [

3]. The reason for this is that service planners try to meet most individual needs even with low performance limits, which fragments the network, and the consequences are not beneficial at all [

4].

The frequency of services is also essential for the perception of public transport [

5]. As excessively long waiting times can have a major impact on the competitiveness of transport services, it is important to identify which specific values are still considered acceptable or explicitly attractive by passengers. The average waiting time per passenger is a key indicator of service reliability [

6], and minimizing it is essential, as passengers perceive waiting time more negatively than in-vehicle time [

7].

These two important factors are examined in this paper, using a specific city as an example. The structure of the paper is as follows.

Section 2 reviews the previous research on the above topics and their main findings.

Section 3 describes the methods which can be used to study certain settlements, particularly the indicators that allow comparison.

Section 4 introduces Győr, the location of the case study presented in this paper, which is situated in Western Hungary.

Section 5 illustrates the practical application of the methods in Győr, by calculating the proposed indicators (quantitative analysis) and examining the feasibility of the solutions proposed in the literature (qualitative analysis), as well as presenting the passenger requirements related to service frequency.

Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Previous Research

In addition to the basic indicators of public transport planning, such as the number of lines, the net and gross network length, and the overlap ratio [

8], there are several approaches to express the complexity of the network. Horváth [

9] interpreted public transport networks as graphs and investigated the distribution of their network, line, and departure level connectivity numbers, using the results of network science. In contrast, Gallotti et al. [

10] started from the cognitive abilities of passengers: they found that the visual memory of the majority of passengers can efficiently handle trips with up to two transfers; in more complex cases, their cognitive limits may cause problems. Since, in small and medium-sized settlements (including the city studied in this paper), it is often possible to get from anywhere to almost anywhere with only one transfer (in the city centre), the need for more than two transfers does not arise; there are, nevertheless, difficulties in the clarity of the networks, even for journeys without transfers. Because of this phenomenon, this paper will further explore this issue from a different angle.

Several studies on the efficient and attractive design of public transport networks have been published under the leadership of Nielsen and Lange. They reviewed two typical, contrasting philosophical directions in network design [

11], the Bangkok model and the Zurich model, based on research by Mees [

12]. Of the two models, Nielsen and Lange proposed the implementation of the supply-oriented Zurich model, the main elements of which are: public transport should be a viable, attractive alternative to car travel, serving the needs of as many traveller groups as possible, with standardized and simplified services, full area coverage, and long-term stability, avoiding parallel lines [

11]. The concept also includes a significant role for planned and quality transfers to eliminate the need for multiple and difficult-to-remember lines, but also requires adequate information for passengers [

13]. The model is supported by the finding that public transport passengers require considerable emotional and intellectual effort to collect, interpret, and put into practice the necessary information [

14].

Nielsen et al. [

15] provided specific suggestions for design principles of attractive networks. Rather than taking into account individual travel needs, they suggested creating lines that are as clear as possible and can accommodate a wide range of passenger flows. Straight lines with high frequencies, following the natural axes of the settlement, allow an efficient system to be created if suitable transfer facilities are available: this is called the “network effect”. It may also be useful to merge lines running adjacent to each other to create more robust lines. A simple example is illustrated in

Figure 1: instead of two lines with relatively low service frequency, a much more robust line with higher service frequency can be created by using the same mileage, i.e., at essentially the same cost (but of course only if this does not cause significant loss of passenger interest in terms of the last mile problem, i.e., the arising walking distances are only minimally affected and do not increase to an unacceptable extent).

The principles also include making lines as long as possible (e.g., using diagonal type lines rather than radial type lines), which, in addition to significantly reducing the number of forced transfers, simplifies the network design and makes it clearer to the passengers [

15].

The importance of service frequency has also been examined in several previous studies. In Norway, a study in eight settlements showed that in cities where departure intervals of local public transport were reduced, the number of passengers increased by 5–6% in the first year [

16]. And in Budapest, an online survey found that 65% of respondents were satisfied with the service frequency, mainly due to the fact that public transport in the Hungarian capital has typically small departure intervals on most lines [

17]. A survey in Hong Kong [

18] and a survey on demand-responsive public transport among young people in Sweden [

19] also confirmed that, if there is sufficient service frequency, traditional public transport can remain competitive with demand-responsive transport (DRT) services.

In his book “Human Transit”, Walker emphasizes the importance of network complexity and service frequency, too [

20]. If the public transport network is too confusing, people need to wade through too many details to figure out which service is useful to them. Walker notes that service frequency is often not given sufficient weight, resulting in services that may be very fast, but which do not arrive when people need them. Similarly, it can take too much time to transfer between different lines [

20].

Of course, there are a lot of other parameters which affect the quality of public transport services. In addition to the structural and cognitive perspectives, several studies highlight that the actual performance and overall attractiveness of public transport systems are also influenced by various operational factors, such as punctuality, operating speed, balance of demand and supply, and other relevant aspects. Faghihinejad and Machemehl [

21] applied a spatial analysis approach that integrated public transit and bike-sharing networks. They measured demand through socio-demographic indicators (such as population density, car ownership, income, and age) and compared it with service supply represented by operating speed, frequency, and station connectivity. In Montréal, Carvalho and El-Geneidy [

22] applied an evaluation of a newly implemented Bus Rapid Transit corridor using observed operational data such as travel time, headways, and dwell times. They found that measures like dedicated lanes and all-door boarding improved travel times, although some headway irregularity remained due to congestion and signal timing. Olstam et al. [

23] showed, through a traffic simulation, that giving priority to buses in mixed traffic could increase operating speeds and reduce travel-time variability. Similarly, Vuchic [

24] noted that the technical speed of a transit line was affected by geometric and infrastructural constraints, which may limit the potential operating speed of the line, regardless of later operational adjustments. In Gdynia, Wołek et al. [

25], using a survey, showed that punctuality is a major driver of user satisfaction, especially among younger and time-sensitive travellers, and an important element in the overall attractiveness of public transport. However, the main subject of this paper is the design principles of public transport networks and timetables, rather than their operation or technical background. Research into these aspects can be identified as a gap, with other studies placing much less emphasis on these factors.

4. Győr: The Location of the Case Study

Győr is Hungary’s sixth-largest city, a municipal city since 1970, and the capital of Győr-Moson-Sopron County (

Figure 2) [

26]. Due to its advantageous geographical location, which is situated near the border of Austria and Slovakia, the city has undergone significant development since 1990 and has become a popular destination for foreign capital investment. The city has also experienced the settlement of several major global companies, as well as the emergence of new industries, which in turn attracted high-tech foreign and national small and medium-sized enterprises to the area [

26]. At present, the automotive industry is the most significant sector within the city’s economy. It is connected to a number of economic bases, including research and development and education [

26]. The generation of new economic connections has been shown to exert significant effects on the traffic of the existing transport network and its development [

26].

The city’s strategic cross-border location, coupled with the economic growth that commenced in the 1990s, has led to the expansion of Győr’s radius of attraction to 60–80 km, a radius that extends beyond the national border. The repercussions of this phenomenon are manifold, encompassing not only the economic sphere but also vital sectors such as education, the labour market, health, public services, and cultural services [

27]. As a consequence, Győr has evolved into a bona fide regional hub, providing a high standard of living for its population and economic stakeholders [

26].

From a transport perspective, the city is located on the Vienna-Budapest axis, with excellent east–west road, rail, and waterway connections. The international TEN-T and Helsinki corridors are crossed by the road corridor IV (motorway M1) and the Danube VII shipping routes [

26].

The process of suburbanization in Hungary commenced in the latter half of the 1980s; however, it was not until the years following 2000 that this process accelerated. This period also coincided with a significant migration of the population from Győr to the surrounding agglomeration. This was primarily driven by the city’s expanding industrial and economic activities, which exerted a substantial influence on the escalation in real estate prices [

27]. The considerable increase in automobile traffic that has resulted from suburbanization has led to a persistent rise in congestion on the city’s primary thoroughfares, particularly during the morning and afternoon peak hours. This phenomenon can be attributed primarily to the daily commuting patterns of individuals who usually possess two vehicles. Nevertheless, it should be noted that, in addition to commuting to their place of work, the fact that children of commuters continue to attend school in Győr is also of significance. It is a common occurrence for parents to drive their children to school [

28].

Between 1990 and 2024, the city’s population exhibited fluctuations within the range of 127,000 and 132,000, primarily influenced by the city’s economic situation, as shown in

Figure 3 [

29]. The population of Győr decreased by 2% between 2019 and 2024. The decrease in population in recent years was mainly due to the coronavirus epidemic, which has caused many people to move out of the city [

30,

31].

As illustrated in

Figure 4, there has been a substantial decline in the number of passengers using local public transport, with a decrease of over 56% observed between 1990 and 2024. The most significant increase was observed in 2004 when the number of passengers utilizing local public transport increased by more than 24% compared to the previous year. This was due to the fact that in 2004, travel was made free for students. However, this discount was not available the following year, and by 2005, the number of passengers had fallen by 20%. By 2019, this figure had increased to more than 40%. And due to the outbreak of the coronavirus epidemic, the number of carried passengers decreased further by almost 30% (more than 9 million) in 2020 [

31]. This rate remained relatively stable between 2020 and 2021, with only a 28% increase in passenger numbers in 2024. The local public transport network (

Figure 5) currently comprises 65 bus lines; however, many of them operate only a few times a day and serve special needs [

4].

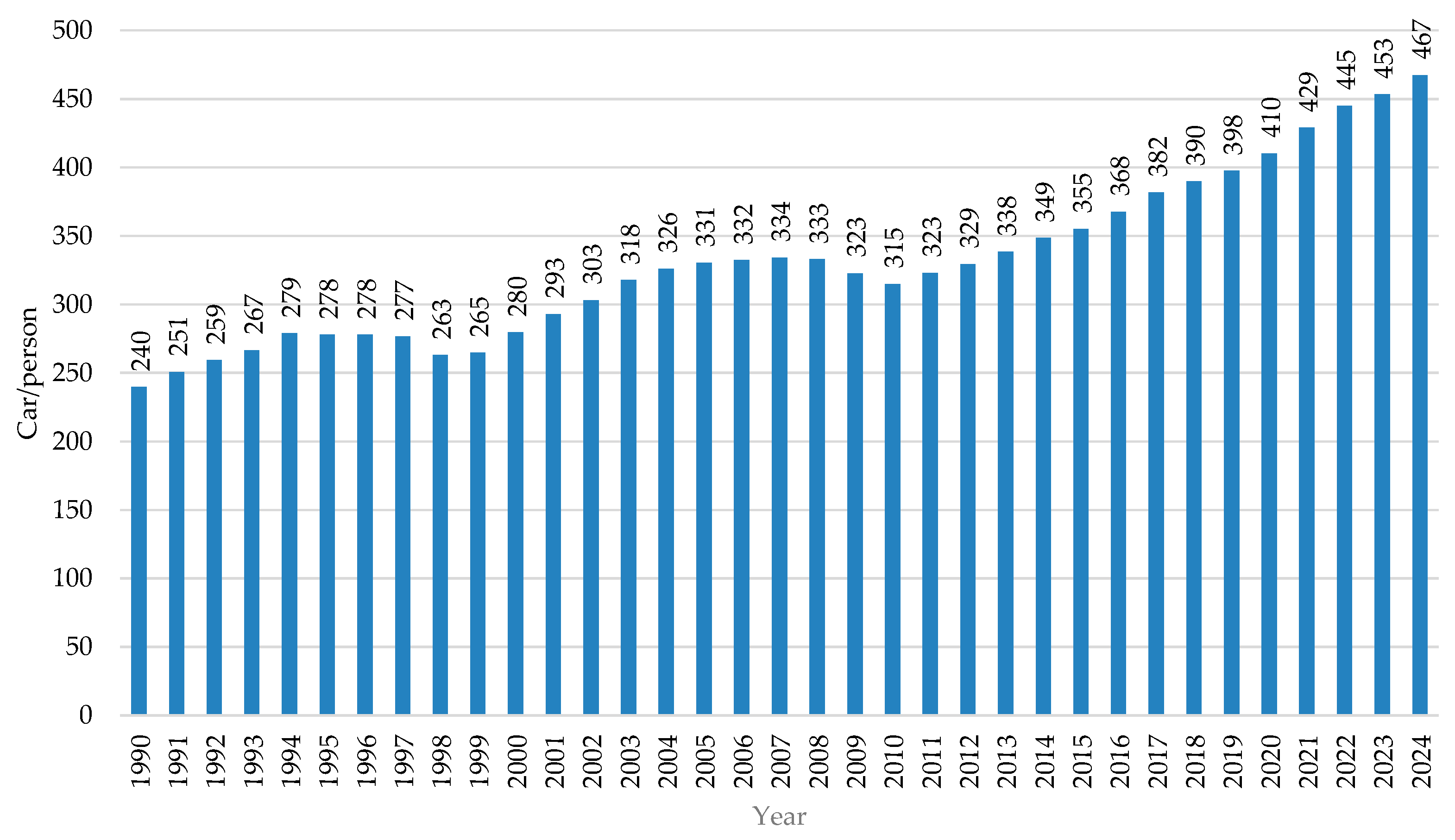

The motorisation level of the city, as demonstrated in

Figure 6, has been growing steadily since 1990, with the exception of two significant declines in 1998 and 2010. From 1990 to 2024, motorisation in Győr increased by 49%. Furthermore, the increasingly widespread use of micro-mobility devices (such as the DOTT electric scooters available also in Győr) is also attracting numerous passengers away from public transport [

32]. These trends support the importance of developing public transport.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Public Transport Indictor Values

Looking at the indicators presented in

Section 3 for Győr, the values in

Table 2 can be calculated. The definition of “core line” has been determined in two different ways, with more lenient and more stringent criteria [

3].

“Core line (1)” means a service with a total of at least 24 services (or 12 services for one-direction, e.g., circular services) on school working days, which means that on average at least 1 departure per direction per hour is guaranteed for 12 h.

“Core line (2)” means a service which, on school working days, operates at least hourly (i.e., provides more or less all-day coverage) in both directions (or in the only direction in case of one-direction, e.g., circular services) for at least 12 h a day.

In general, it is advisable to develop area-specific definitions for individual studies based on local characteristics.

For comparison purposes, the table also includes data on the two other largest cities in Győr-Moson-Sopron County: Sopron and Mosonmagyaróvár [

4]. The reasons for choosing these cities are as follows. Firstly, they are all located within the same county. Secondly, they are all distinguished as university towns. Thirdly, they all have significant industrial parks. The composition and characteristics of the population (e.g., education, salaries, level of motorization) are therefore similar. Furthermore, local public transportation in all three cities is operated by the same company (MÁV Személyszállítási Zrt.), which would not be the case for other nearby counties; e.g., the larger cities in Vas County and Veszprém County have different bus operators. These aspects make these settlements easily comparable. Based on the data, it can be concluded that the smaller cities have a slightly higher level of motorization, whereas the ratio of public transport in the modal split is significantly lower than in Győr (no accurate data is available for Mosonmagyaróvár, but based on empirical evidence, a relatively low value can be estimated).

It is worth noting that the 12 h period in the above definitions is based on a slightly subjective choice, which is supported by the fact that this period is 50% of the hours of the day (which corresponds to the minimum expected “morning to evening” operating time), but other, similar (e.g., 10 or 14) hour values could be used, which would affect the results to some extent. A more detailed examination of this could be a further step in the research.

Several indicators in

Table 2 suggest that Győr’s local public transport network is more complicated than strictly necessary: the overlap ratio is well above 5 (similarly to Sopron and Mosonmagyaróvár), while the ratio of core lines is relatively low according to both calculations (only 35.4% and 24.6%, but still much higher than in Mosonmagyaróvár).

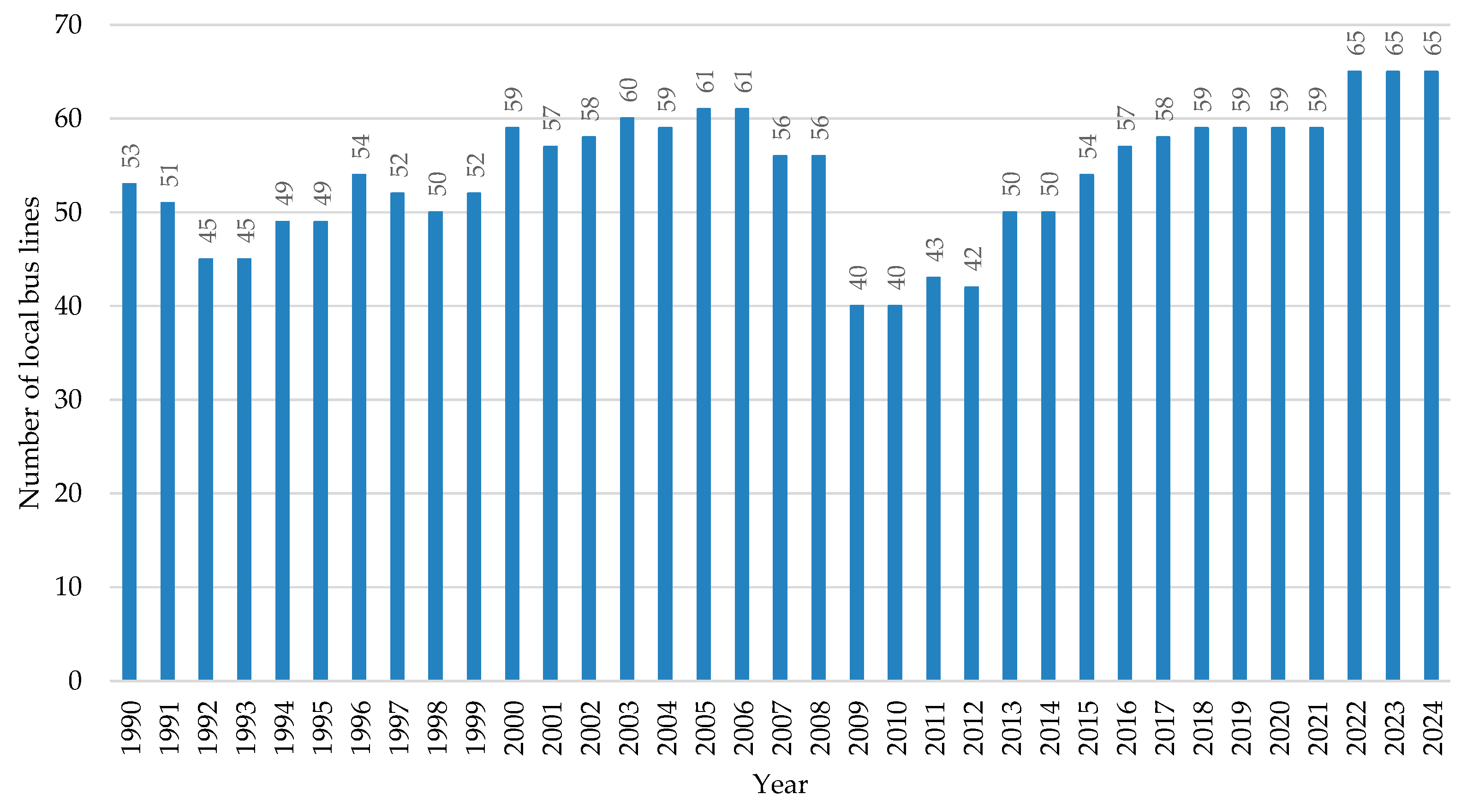

To understand the process by which the above situation has evolved, a historical analysis of the number of lines announced in the timetable (the most easily determinable, yet illustrative indicator) has been carried out for the last 35 years [

4].

Figure 7 shows the number of local bus lines in Győr. (For the years with more different timetables, the value was determined on the basis of the latest effective timetable in the specified year. The values do not include special-purpose lines, e.g., those operating only a few times a year in connection with major city events, e.g., late-evening concerts, celebrations.)

The underlying trend is an increase in the number of lines, which is, of course, also linked to the continuing expansion of the city’s industrial and residential areas, but this alone would not justify such a significant increase. Other reasons are that, in recent years, an increasing number of interurban bus lines have been integrated into the local transport network in order to achieve cost efficiency, but also purely local lines have had to cater for an increasing number of different needs with fewer and shorter mileage limits. This has meant that some of the robust lines have had to be disassembled, with a large number of feeder, detour, and branch lines, in order to meet the needs of as many passengers as possible within the cost limits set by the municipality ordering the service. Such an in-depth consideration of passenger needs reflects an essentially positive design intent; however, it has the unfortunate side effect of greatly increasing network complication.

On the other hand, the sawtooth nature of the graph can also be noticed, which is no coincidence: the city has undergone several comprehensive network redesigns in recent decades, some of which were specifically aimed at rationalizing lines and making the network more compact and easy to understand. In 1992, the number of interurban lines available also for local travel was reduced, while in 2009, a comprehensive network reform was carried out [

35], which reduced the previously overcomplicated network of 56 lines to a system of 40 lines.

5.2. Applicability of the Recommendations from the Literature

The logic of Nielsen and Lange presented in

Section 2 could, in principle, be supported in Győr, but it is important to note that in practice it can only be used with positive results if the mileage and cost limits allow high frequencies. If this cannot be ensured, the elimination of targeted direct lines designed for specific passenger needs (e.g., only needed at a few specific times) would generate more passenger complaints (and even lead to the loss of existing passengers) than there would be benefits of simplifying the network and making it more transparent. Nielsen and Lange [

11] also noted that the method is less applicable in the case of poor passenger flows, in which case they recommend the use of demand-responsive transport (DRT) techniques.

To summarize the findings related to network structure, it is worth exploring the above principles in the development of future network reforms, although it should also be noted that similar methodologies have already been applied in the 2009 Győr network reform [

35]. It is likely that the relatively low mileage limit (~4 million km/year) means that the methodology is currently of limited use in Győr. However, with some additional funding, the situation could change.

5.3. The Required Service Frequencies

The following conclusions can be drawn with regard to service frequencies. In November 2022, a household survey was conducted in Győr to investigate the transport habits of the local population, mainly in terms of public transport [

5]. A total of 2024 people were interviewed, of which 958 (47.3%) were male and 1066 (52.7%) female, which reflects the actual gender composition of the population of Győr (47.46% male and 52.54% female). Similarly, age and highest level of education were also taken into account during the survey as representativeness factors. Therefore, the sample can be considered representative.

Of the respondents, 401 said that they used local public transport with some regularity, of which 30.8% used it daily, 54% used it several times a week, 10.1% used it weekly, and only 5.1% said that they used it occasionally.

The results of the questionnaire clearly showed that many people, nearly 300, would switch from car to public transport if buses were more frequent. In the specific question on service frequency, the highest number of respondents (142) indicated that they would be most satisfied with a departure interval of 10 min (

Figure 8), followed by 20 min (101 respondents) and 15 min (40 respondents). (This question was answered by respondents who stated that they would switch to public transport if service frequencies were higher. It must be noted that there is a large group of people who would not switch to public transport under any circumstances [

5].)

Since the 10 min interval expected by most passengers is only available on a small number of lines (or line groups) and is not available anywhere in Győr during off-peak hours, furthermore, 20 min interval is also only available on certain lines and during certain periods, the result is a serious criticism of the current level of service and also indicates a major direction for possible and necessary improvements.

It is important to emphasize that the departure intervals shown in

Figure 8 do not necessarily represent waiting times but the time between services. The actual average waiting time is half of this in the case of frequent services, while in the case of less frequent services, passengers tend to arrive at the stops at the appropriate time. This means that those who depart, e.g., from home or work, can adjust to the timetable within certain limits, so they do not have to wait long even if the departure interval is longer. This is why a 20 min frequency is acceptable to many respondents [

5].

Of course, meeting public transport demand in terms of quantity, i.e., providing sufficient capacity, is an important and natural aspect of timetable planning, too. The fulfilment of these quantitative requirements was considered essential; therefore, this paper does not examine them in detail.

6. Conclusions

It can be concluded that ensuring a network is as simple as possible, and thus easy for passengers to understand and remember, can play a significant role in the popularity of public transport systems and in attracting new passengers. However, funding constraints often make it difficult to develop such robust networks of high-frequency lines. Nevertheless, it is advisable to keep the proliferation of lines within reasonable limits. The first step in this direction could be to review the justification for the existence of slightly different lines: in many cases, these reasons are probably no longer relevant and only existed in the past. In this case, a number of lines can be unified.

Where the number of lines is higher than ideal but cannot be avoided without a significant loss of passenger interest, a separate network map of the core lines (which can be widely disseminated) should be considered, while additional lines (e.g., for labour transport) can be shown on a supplementary network map, if necessary, targeted at the stakeholders.

Finally, it is also important to mention a widespread view that many of the above issues (such as the complication of the network and the number of lines, the nature of timetables, etc.) are becoming increasingly irrelevant, as the vast majority of passengers now use computer- and mobile phone-based travel planning services, and therefore do not need to understand and remember the network and timetable. This may indeed change in the future, but for the moment, the problems described above still exist, and it is worth focusing on the issues investigated in this paper. Furthermore, it can be stated that, even in the longer term, a public service that does not require the use of a journey planner application every time will be more attractive.

This paper is only a first step in the related research, which shall be continued via population surveys, looking at other cities, and searching for good practices.