Integrating Sustainable City Branding and Transport Planning: From Framework to Roadmap for Urban Sustainability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology for the Conceptual Framework

3. Theorical Background on Sustainable City Branding

3.1. Introduction to Place and City Branding

3.2. Evolution Toward Sustainable City Branding (SCB)

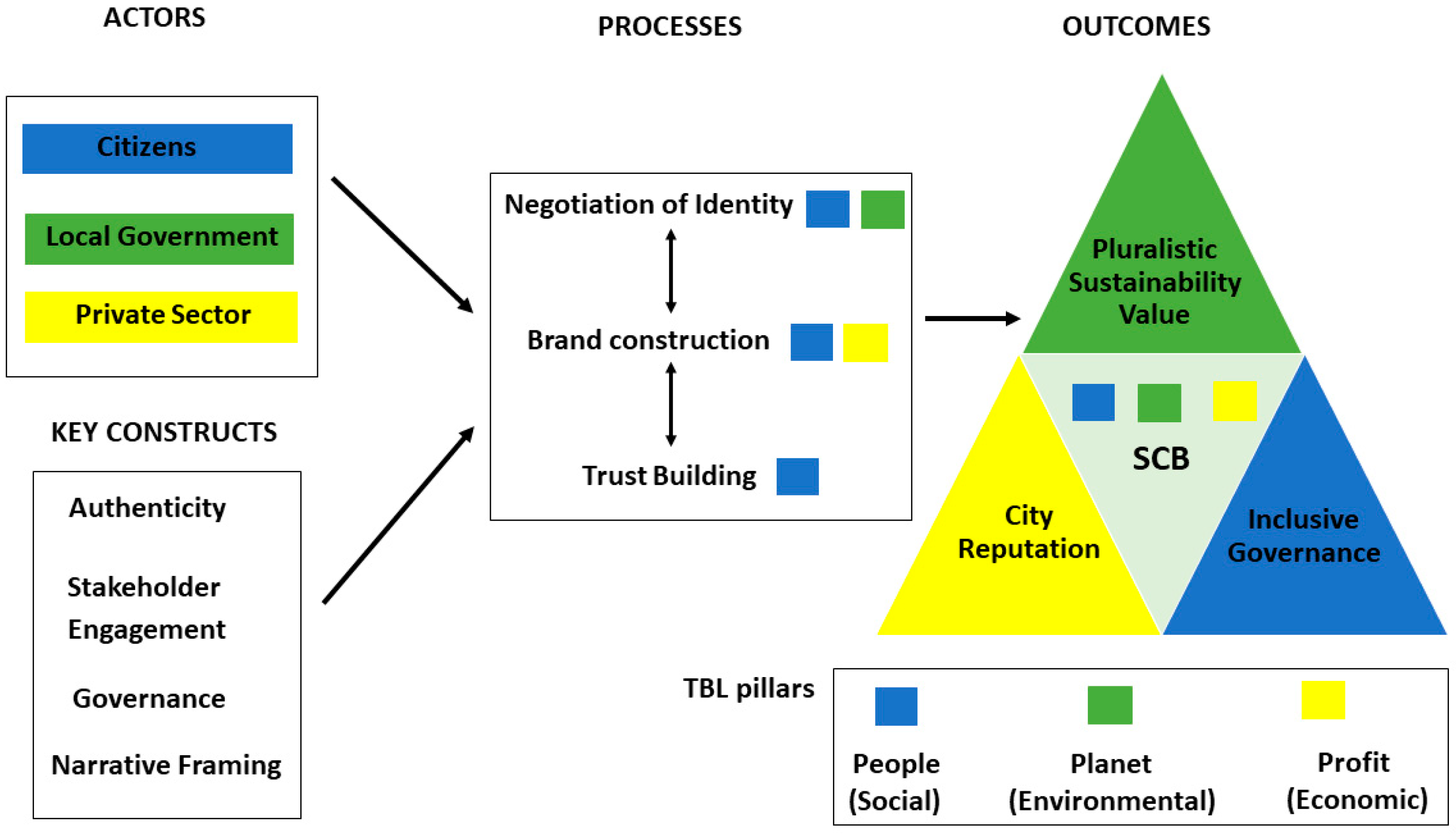

3.3. Core Dimensions of SCB

3.4. Applications and Studies in Sustainable City Branding

4. Framework for Sustainable City Branding Applied to Transport Planning

5. Evaluation of Sustainable City Branding Performance

6. Contribution and Novelty

- Explicit integration with transport planning. While earlier frameworks focus on branding or sustainability independently, our model directly links SCB with sustainable mobility as a lever for urban transformation.

- Participatory and digital dimensions. Unlike traditional frameworks, the proposed framework emphasizes citizen science, co-creation, and real-time monitoring via digital tools, ensuring responsiveness to community needs.

- Policy roadmap alignment. The framework is operationalized into a concrete multi-phase roadmap for municipal decision-makers, bridging the gap between theory and practical implementation.

7. Challenges and Risks in Sustainable City Branding

8. Research Gaps and Future Direction

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbasov, R. Cities on the Frontlines: Why Urbanization Must Adapt to the Climate Crisis. Modern Diplomacy. 2025. Available online: https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2025/03/17/cities-on-the-frontlines-why-urbanization-must-adapt-to-the-climate-crisis/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- IEA. Empowering Urban Energy Transitions; IEA: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/empowering-urban-energy-transitions (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Brundtland, G.H. Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development; Brundtland Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 1987; UN-Dokument A/42/427; Available online: http://www.un-documents.net/ocf-ov.htm (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Elkington, J. Chapter 1—Enter the Triple Bottom Line. In The Triple Bottom Line Does It All Add Up; Henriques, A., Richardson, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; Available online: https://johnelkington.com/archive/TBL-elkington-chapter.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Elkington, J. Towards the Sustainable Corporation: Win-Win-Win Business Strategies for Sustainable Development. Calif. Manage. Rev. 1994, 36, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Yu, Y.; Yang, S.; Lv, Y.; Sarker, M.N. Urban Resilience for Urban Sustainability: Concepts, Dimensions, and Perspectives. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, S.; Mahmoud, I.H.; Arlati, A. Integrated Collaborative Governance Approaches towards Urban Transformation: Experiences from the CLEVER Cities Project. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresciani, S.; Rizzo, F.; Mureddu, F. Social Innovation and Co-design for Climate Neutrality: The NetZeroCities Project. In Assessment Framework for People-Centred Solutions to Carbon Neutrality: A Comprehensive List of Case Studies and Social Innovation Indicators at Urban Level; Bresciani, S., Rizzo, F., Mureddu, F., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapucu, N.; Ge, Y.; Rott, E.; Isgandar, H. Urban resilience: Multidimensional perspectives, challenges and prospects for future research. Urban Gov. 2024, 4, 162–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucaro, A.; Agostinho, F. Urban Sustainability: Challenges and Opportunities for Resilient and Resource-Efficient Cities. Front. Sustain. Cities 2025, 7, 1556974. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/sustainable-cities/articles/10.3389/frsc.2025.1556974 (accessed on 9 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- United Nations (UN). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/70/1). 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/publications/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Arcadis. Top 5 Sustainable Cities. Available online: https://www.arcadis.com/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Aydoghmish, F.M.; Rafieian, M. Developing a comprehensive conceptual framework for city branding based on urban planning theory: Meta-synthesis of the literature (1990–2020). Cities 2022, 128, 103731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peldon, D.; Banihashemi, S.; LeNguyen, K.; Derrible, S. Navigating urban complexity: The transformative role of digital twins in smart city development. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 111, 105583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Liu, R.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y. The Fundamental Issues and Development Trends of AI-Driven Transformations in Urban Transit and Urban Space. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 126, 106422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Ma, L.; Broyd, T.; Chen, W.; Luo, H. Digital twin enabled sustainable urban road planning. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 78, 103645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukic Vujadinovic, V.; Damnjanovic, A.; Cakic, A.; Petkovic, D.R.; Prelevic, M.; Pantovic, V.; Stojanovic, M.; Vidojevic, D.; Vranjes, D. AI-Driven Approach for Enhancing Sustainability in Urban Public Transportation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omrany, H.; Mehdipour, A.; Oteng, D. Digital Twin Technology and Social Sustainability: Implications for the Construction Industry. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yue, Q.; Lu, X.; Gu, D.; Xu, Z.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, S. Digital twin approach for enhancing urban resilience: A cycle between virtual space and the real world. Perform.-Based Eng. Cityscape Resil. 2024, 3, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, E.; Schneider, M.; Somanath, S.; Yu, Y.; Thuvander, L. Sentiment and semantic analysis: Urban quality inference using machine learning algorithms. iScience 2024, 27, 110192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouhani, S.; Mozaffari, F. Sentiment analysis researches story narrated by topic modeling approach. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2022, 6, 100309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, C.; Bibri, S.E.; Longchamp, R.; Golay, F.; Alahi, A. Urban Digital Twin Challenges: A Systematic Review and Perspectives for Sustainable Smart Cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 99, 104862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logar, E. Place branding as an approach to the development of rural areas: A systematic analysis of web of science ‘geography’ literature. GeoJournal 2025, 90, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshuis, J.; González, L.R. Conceptualising place branding in three approaches: Towards a new definition of place brands as embodied experiences. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2025, 18, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshuis, J.; Klijn, E.H. City branding as a governance strategy. In The Handbook of New Urban Studies; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 92–105. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Managing Customer-Based Brand Equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croad, J.; Lincoln, A. Sustainable City Branding. In Encyclopedia of Sustainable Management; Idowu, S.O., Schmidpeter, R., Capaldi, N., Zu, L., Del Baldo, M., Abreu, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 3415–3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albino, V.; Berardi, U.; Dangelico, R.M. Smart Cities: Definitions, Dimensions, Performance, and Initiatives. J. Urban Technol. 2015, 22, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garanti, Z.; Ilkhanizadeh, S.; Liasidou, S. Sustainable Place Branding and Visitors’ Responses: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Oliveira, E.H. Place Branding in Strategic Spatial Planning: An Analysis at the Regional Scale with Special Reference to Northern Portugal. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti, J.; Çakmak, E.; Dinnie, K. The competitive identity of Brazil as a Dutch holiday destination. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2011, 7, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, L.R.; Gale, F. Sustainable city branding narratives: A critical appraisal of processes and outcomes. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2023, 16, 20–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-J. Green city branding: Perceptions of multiple stakeholders. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2019, 28, 376–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berntzen, L.; Johannessen, M.R. The Role of Citizen Participation in Municipal Smart City Projects: Lessons Learned from Norway. In Smarter as the New Urban Agenda: A Comprehensive View of the 21st Century City; Gil-Garcia, J.R., Pardo, T.A., Nam, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginesta, X.; de-San-Eugenio-Vela, J.; Corral-Marfil, J.-A.; Montaña, J. The Role of a City Council in a Place Branding Campaign: The Case of Vic in Catalonia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Y.-M.; Seo, B. Transformative city branding for policy change: The case of Seoul’s participatory branding. Environ. Plan. C 2018, 36, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juarez, L.; Metaxas, T.; Olmos, G.F. Branding Madrid as a Sustainable City: The role of Mega Projects. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 12, 235–256. [Google Scholar]

- Bisani, S.; Daye, M.; Mortimer, K. Legitimacy and inclusivity in place branding. Ann. Tour. Res. 2024, 109, 103840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão, A.; Magalhães, F. Please tell me how sustainable you are, and I’ll tell you how much I value you! The impact of young consumers’ motivations on luxury fashion. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2287786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmetyinen, A.; Nieminen, L.; Aalto, J.; Pohjola, T. Enlivening a place brand inclusively: Evidence from ten European cities. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2025, 21, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paganoni, M.C. City Branding and Social Inclusion in the Glocal City. Mobilities 2012, 7, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, C.; Mehmood, A.; Marsden, T. Co-created visual narratives and inclusive place branding: A socially responsible approach to residents’ participation and engagement. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginesta, X.; de San Eugenio, J. Rethinking Place Branding From a Political Perspective: Urban Governance, Public Diplomacy, and Sustainable Policy Making. Am. Behav. Sci. 2021, 65, 632–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.C.; Pereira, C.R.; Lopes, M.F.; Calisto, R.A.R.; Vale, V.T. Sustainable and Green City Brand. An Exploratory Review Alternate title: Marca Ciudad Sostenible y Verde. Una revisión exploratoria. Cuad. Gest. 2023, 23, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginesta, X.; Cristòfol, F.J.; Eugenio, J.S.; Martínez-Navarro, J. The Role of Future Generations in Place Branding: The Case of Huelva City. Polit. Gov. 2024, 12, 7730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulides, G.; de Chernatony, L. Consumer-Based Brand Equity Conceptualisation and Measurement: A Literature Review. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2010, 52, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyduk, H.B.B.; Okan, E.Y. Sustainable City Branding: Cittaslow—The Case of Turkey. In Global Place Branding Campaigns Across Cities, Regions, and Nations; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alp, G.Ö. Cittaslow through the lens of sustainable urban development: A comparative analysis of Italy and Türkiye cases. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2024, 11, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsolaki, A.; Metaxas, T. Multiculturalism as a factor in economic development and city branding: The case of Komotini, Greece. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2024, 21, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuculescu, L.; Luca, F.A. Developing a Sustainable Cultural Brand for Tourist Cities: Insights from Cultural Managers and the Gen Z Community in Brașov, Romania. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.S. How to brand a city to appeal to young consumers: A qualitative study. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2025; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Edelenbos, J.; de Jong, M. Between branding and being: How are inclusive city branding and inclusive city practices related? J. Place Manag. Dev. 2025, 18, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokolo, A.J. Examining Sustainable Mobility Planning and Design for Smart Urban Development in Metropolitan Areas. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Sustainable and Smart Mobility Strategy: Putting European Transport on Track for the Future. Office of the European Union, 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52020DC0789 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Acadis. Making Sustainable Choices. 2024. Available online: https://annualreport.arcadis.com/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- ISO 37120:2018; Sustainable Cities and Communities—Indicators for City Services and Quality of Life. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- ISO 37122:2019; Sustainable Cities and Communities—Indicators for Smart Cities. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- ISO 37123; Sustainable Cities and Communities—Indicators for Resilient Cities. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Venkatesh, G. A critique of the European Green City Index. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2014, 57, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 37101:2016; Sustainable Development in Communities—Management System for Sustainable Development—Requirements with Guidance for Use. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Florek, M.; Hereźniak, M.; Augustyn, A. Measuring the effectiveness of city brand strategy. In search for a universal evaluative framework. Cities 2021, 110, 103079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçak, A.I.; Akten, M. Analyzing the Effects of Urban Sustainability Assessment Tools on City Branding: YeS-TR Case. J. Archit. Sci. Appl. 2023, 8, 1034–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C. Comparisons of the City Brand Influence of Global Cities: Word-Embedding Based Semantic Mining and Clustering Analysis on the Big Data of GDELT Global News Knowledge Graph. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Christodoulou, A. Review of sustainability indices and indicators: Towards a new City Sustainability Index (CSI). Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2012, 32, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Hong, J.; Lee, S. Development of Brand Evaluation Elements in Sustainable Cities. Arch. Des. Res. 2025, 38, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIRED. IMACLIM. Available online: https://www.iamcdocumentation.eu/index.php/Model_Documentation_-_IMACLIM (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Akturan, U. How does greenwashing affect green branding equity and purchase intention? An empirical research. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2018, 36, 809–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuetze, T.; Chelleri, L. Urban Sustainability Versus Green-Washing—Fallacy and Reality of Urban Regeneration in Downtown Seoul. Sustainability 2016, 8, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J. Greenwashing: Appearance, illusion and the future of ‘green’ capitalism. Geography Compass 2024, 18, e12736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbinza, Z.E. Connecting place branding to social and governance constructs in Johannesburg, South Africa. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2024, 20, 408–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herstein, R.; Berger, R.; Jaffe, E. Five typical city branding mistakes: Why cities tend to fail in implementation of rebranding strategies. J. Brand Strategy 2014, 2, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, K.R.; Bertilsson, J.; Rennstam, J. Climate crisis as a business opportunity: Using degrowth to defamiliarize place branding for sustainability. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2025, 21, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winit, W.; Kantabutra, S.; Kantabutra, S. Toward a Sustainability Brand Model: An Integrative Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlo, O. Delivering Brand Resilience in the Digital Era. Available online: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/business-school/ib-knowledge/marketing/delivering-brand-resilience-the-digital-era/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Berga, M.; Gomes, S. Participatory Design: Bringing Users to the Design Process. Available online: https://www.imaginarycloud.com/blog/participatory-design (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Ramadhani, I.S.; Indradjati, P.N. Toward contemporary city branding in the digital era: Conceptualizing the acceptability of city branding on social media. Open House Int. 2023, 48, 666–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunkan, D.V.; Ogunkan, S.K. Exploring big data applications in sustainable urban infrastructure: A review. Urban Gov. 2025, 5, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, K. Crafting Sustainable Brand Narratives Through Immersive Technologies: The Role of Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR). In Compelling Storytelling Narratives for Sustainable Branding; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Project Type | Impact on Sustainable City Branding |

|---|---|

| 1a. Electrification of railway networks | Visually reinforce the city’s image as environmentally responsible and nature-integrated; create photo-friendly |

| 1b. Green rail corridors | Demonstrate commitment to reducing carbon emissions |

| 1c. Solar-powered railway stations | Showcases technological innovation and renewable energy leadership, appealing to green investors |

| 1d. Regenerative braking systems in trains/metros/trams | Positions the city as energy-efficient |

| 1e. Sustainable station design with green roofs and walls | Emphasizes user-centric, climate-conscious design that strengthens the city’s image as progressive and people-focused, while visibly demonstrating a commitment to green urban aesthetics and climate resilience |

| 1f. Stormwater management systems | Underlines resilience and climate adaptation are important in cities that market themselves as prepared for future environmental challenges |

| 1g. Use of recycled and sustainable materials | Conveys environmental responsibility and innovation in construction, enhancing the credibility of a city’s green brand |

| 1h. adaptive reuse of rail and road infrastructures | Narrates a story of heritage preservation, urban regeneration, and the principles of a circular economy |

| 2a. Intelligent traffic management systems (ITMS) using sensors and AI to optimize traffic light timings and reduce congestion | Positions the city as innovative and efficient in managing urban mobility and sustainability |

| 2b. Electric vehicle charging Infrastructure | Reinforces a city’s identity as clean energy-oriented |

| 2c. Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) platforms | Elevates the city’s status as a smart city, focusing on seamless, eco-friendly transportation solutions |

| 2d. Smart parking solutions to provide real-time availability of parking spaces and guide drivers to the nearest open spot | Enhances the city’s image as a tech-savvy and environmentally conscious urban hub |

| 2e. Bike and car sharing programs | Projects the city as innovative, with a focus on shared mobility and sustainable transport options |

| 2f. Smart streetlights with environmental sensors | Reinforces the city’s reputation as an environmentally conscious, smart, and sustainable place |

| KPI | Units |

|---|---|

| Social Pillar | |

| Citizen engagement levels | % of population participating in events |

| Perceived safety | survey score, e.g., (1–10) |

| Inclusivity in transport access | % of underserved neighborhoods with adequate service |

| Public transport satisfaction | survey score, e.g., (1–10) |

| Active mobility share | % of trips by transport mode |

| Environmental Pillar | |

| CO2 emissions per capita from travel | kg CO2 per capita per year |

| Green transit corridor coverage | km of corridor per 100,000 inhabitants |

| Adoption of low-emission transport modes | % of fleet that is electric/low-emission |

| Air quality improvement | µg/m3 reduction in PM2.5/NOx |

| Energy consumption per km | kWh per passenger-km |

| Economic Pillar | |

| Local green business participation | % of transport-related businesses certified green |

| Transport-related job creation | number of jobs created |

| Cost-efficiency of sustainable mobility initiatives | € per passenger-km |

| Investment in green transport infrastructure | € per year or per capita |

| Public–private partnership projects | number of initiatives |

| Governance Pillar | |

| Municipal departments adopting SCB principles | % of municipal departments |

| Projects incorporating equity considerations | % of total transport projects |

| Frequency of independent performance audits | number per year |

| Stakeholder engagement quality | survey score, e.g., (1–10) |

| Transparency in reporting | number of published reports or datasets |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vale, C.; Vale, L. Integrating Sustainable City Branding and Transport Planning: From Framework to Roadmap for Urban Sustainability. Future Transp. 2025, 5, 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040172

Vale C, Vale L. Integrating Sustainable City Branding and Transport Planning: From Framework to Roadmap for Urban Sustainability. Future Transportation. 2025; 5(4):172. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040172

Chicago/Turabian StyleVale, Cecília, and Leonor Vale. 2025. "Integrating Sustainable City Branding and Transport Planning: From Framework to Roadmap for Urban Sustainability" Future Transportation 5, no. 4: 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040172

APA StyleVale, C., & Vale, L. (2025). Integrating Sustainable City Branding and Transport Planning: From Framework to Roadmap for Urban Sustainability. Future Transportation, 5(4), 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040172