1. Introduction

Population aging and digital transformation are the two important trends of society, where digital transformation can become a potential solution for resolving the issues arising from population aging [

1]. Transferring many physical travel activities to online offers the modern travel process significant opportunities to become more flexible and service oriented [

2]. Digital tools and the Internet provide passengers with more travel options, especially in air travel. As an industry that prioritizes innovation, the air transport industry is a pioneer in applying digital technologies and relevant tools to its services and products [

3]. These digital tools bring changes such as online ticketing and self-check-in to the industry.

However, the question is whether older passengers are willing to accept these changes. Although an increasing number of older adults, especially young-old ones, are integrating digital tools into their daily lives, air travel activities such as check-in and security screening still pose considerable challenges. These processes sometimes require technological proficiency, which may be limited among older individuals, particularly those with declining cognitive or physical abilities. The use of digital technologies, such as mobile check-in apps, automated kiosks, and biometric gates, can help streamline these procedures, reduce waiting times, and improve efficiency. However, it is essential to assess whether these digital tools truly meet the needs of older passengers as effectively as they do for younger populations.

Older passengers often prioritize factors such as accessibility, health and safety, user-friendliness, and convenience in their travel experiences [

4,

5,

6]. Satisfying their travel demands and needs can improve older passenger satisfaction and has the potential to encourage repeat air travel, which may support broader social and economic sustainability goals by promoting inclusive air travel and increasing long-term customer retention for the aviation industry.

This study explores older passengers’ attitudes, behavior, and evaluations of digital air travel, as well as the impact of digital technologies on this demographic, using China as a case study. Due to physical and health-related limitations that often restrict independent travel among the oldest age groups, the research specifically focuses on the young-old demographic (ages 50–64), who are more likely to travel independently and engage with digital systems. A structured survey was conducted to assess older passengers’ attitudes and behavior patterns towards digital air travel. Drawing upon the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), this study provides a comprehensive analysis of how perceived usefulness, ease of use, and behavioral intentions influence older passengers’ adoption of digital technologies. Finally, the results are used to assess whether digital technology can act as a sustainable motivator for continued air travel among this population and to offer practical recommendations for improving accessibility and long-term adoption.

3. Research Method

3.1. Sampling

The main research method in this study is a questionnaire survey conducted among passengers primarily living or working in mainland China [

22]. Participants were recruited using a random sampling method via an online portal. China was selected as a case study due to its vast market, which, in terms of area and population, is comparable to a continent. Also, according to the World Health Organization (2025), ‘China has one of the fastest-growing aging populations in the world.’ [

23]. Additionally, as one of the world’s largest and fastest-growing aviation markets [

24], China provides an ideal setting to examine the impact of digital tools on older air passengers.

To analyze the digital impact on older passengers’ travel behavior, all participants were over 50 years old. This age limit was chosen because the minimum retirement age in China is 50 years old [

25]. Furthermore, passengers aged 65 and above often require additional support and may face challenges traveling independently, which can restrict their interaction with digital technologies in the context of air travel. Therefore, targeting individuals aged 50 to 64 for sampling in this study is reasonable. A total of 301 responses were collected, with 256 being valid. In China, the number of people choosing to travel by high-speed rail significantly surpasses those opting for air travel. For example, in 2023, the number of Chinese people transported by air (619.58 million) was approximately 16.84% of those transported by railway (3.68 billion) [

26,

27]. Moreover, this study aims to investigate the air travel behavior of older passengers, a group that is much smaller in number compared to younger generations. Therefore, this volume of collected data is as expected and reasonable.

Since the study’s primary aim is to examine how older passengers evaluate digital tools’ influence on their air travel, it is essential to focus on those who already possess at least a basic level of digital competency. As such, the online survey method also functioned as a screening tool, ensuring the inclusion of participants relevant to the study’s research focus. Among all the valid responses, the gender distribution was 52.0% female, 47.2% male, and 0.8% prefer not to say, indicating no significant gender bias.

Table 1 shows the summary statistics of respondents.

3.2. Research Scope and Sampling Limitation

The use of an online survey as the primary data collection method inevitably restricted participation to older passengers with access to and basic familiarity with digital technologies. While this introduces a sampling bias, it was also a necessary methodological choice aligned with the study’s focus on digital air travel. The research specifically aimed to assess how older passengers engage with and evaluate digital services in air travel. Therefore, targeting respondents who are at least minimally digitally literate ensured that the data collected were both relevant and meaningful to the study’s objectives. In this context, the online survey served not only as a data collection tool but also as a screening mechanism to identify individuals within the older demographic who have had some interaction with digital platforms.

Nonetheless, this approach may limit the generalizability of the findings. Older passengers who are less digitally engaged, such as those with limited internet access, low digital literacy, or no prior experience with air travel, are likely underrepresented. As such, the study may not fully capture the barriers faced by the most digitally excluded segments of the older population. Future research could address this gap by incorporating additional methods, such as in-person interviews or paper-based surveys, which would enable broader demographic representation and enrich the understanding of digital exclusion.

Based on classifications from the World Health Organization [

23] and demographic trends in China, older passengers were classified into two groups: young-old (50–64 years old) and old-old (65+ years old). National transportation data indicate that passengers aged 65 and above represent the smallest proportion of total air travelers, as well as the lowest increasing rate compared to other age groups [

28]. As many old-old passengers may require additional assistance from family members or airport staff due to physical limitations or health-related concerns, this can significantly shape their travel behavior and reduce their engagement with independent digital tools. This targeted sampling produced 301 responses, with 256 valid, which is appropriate for an exploratory study but limits representativeness. The study does not capture the perspectives of digitally excluded or “old-old” (65+) passengers, which should be addressed in future research. The sample (

n = 256) represents only digitally literate ‘young-old’ passengers and is not nationally representative of China’s older population. Future work should use stratified and larger samples covering diverse regions.

Given these circumstances, this study focuses on the younger segment of the older demographic, the young-old, who are more likely to travel independently and interact with digital services during their journey. This focus ensures that the research aligns with the study’s aim of evaluating how digital tools impact the travel behavior and attitudes of older passengers who are functionally able to use such technologies.

3.3. Procedure

Based on the main research aim of this study, the questionnaire consists of two parts. Part 1 includes participants’ demographic information, such as gender, travel purpose, and travel frequency. Part 2 focuses on participants’ experiences and evaluations of current digital air travel tools. It includes questions about their satisfaction with these tools, their desired features, and their overall impressions. This section aims to assess how well existing digital tools meet the needs of older passengers and identifies areas for improvement. The main questions cover the following:

Travel behavior: Participants’ travel behavior at various stages of their journey.

Attitude towards digital tools: Participants’ attitudes towards the use of digital air travel tools.

Future intentions: Participants’ intentions regarding the use of digital air travel tools and their sustainable choice of air travel in the future.

The research aim is central to the question design, and all questions were developed considering the literature review and background.

3.4. Data Analysis

The data analyzed in this study were primarily collected through the survey. Since the development, the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) have been widely used in travel-related research to analyze and predict passenger behavior and intentions regarding technology [

29]. TAM is used to assess user acceptance of new e-technologies or e-services, focusing on the relationship between users’ beliefs about a technology’s usefulness and their willingness to use it [

30]. TAM constructs of perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU) were operationalized through a set of survey items covering specific travel stages (flight booking, check-in, security, luggage claim, after-services). Participants evaluated these items using multiple-choice questions, and their responses were converted to unit percentage (UP, %) scores. The TPB analysis applied a hybrid deductive–inductive approach. Survey responses were coded into meaning units (MUs) and mapped to TPB’s core constructs: attitudes (ATTs), subjective norms (SNs), and perceived behavioral control (PBC). This approach ensured internal construct validity by cross-referencing TAM and TPB outcomes. To strengthen the measurement of constructs, the TAM and TPB scales were further evaluated for reliability and validity. For the TAM, perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU) were each measured by multiple indicators across travel stages (booking, check-in, security, baggage claim, after-services). For TPB, attitudes (ATTs), subjective norms (SNs), and perceived behavioral control (PBC) were assessed using meaning units (MUs) coded from open-ended responses. For reliability testing, internal consistency was assessed through Cronbach’s alpha. The TAM constructs demonstrated high reliability, with α = 0.84 for PU and α = 0.81 for PEOU. Similarly, TPB constructs showed satisfactory levels: ATT (α = 0.78), SN (α = 0.76), and PBC (α = 0.82). All construct levels exceeded the 0.70 threshold, generally regarded as acceptable in behavioral studies, confirming that the items consistently measured the intended constructs.

For validity testing, the construct validity was examined using exploratory factor analysis (EFA). The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (0.79) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (p < 0.001) indicated that the data were suitable for factor analysis. Factor loadings showed that survey items clustered strongly on their intended constructs, supporting both convergent and discriminant validity. In addition, triangulation across TAM and TPB confirmed that constructs aligned theoretically: for example, high PU and PEOU corresponded with positive attitudes (ATTs) and stronger behavioral intentions. Content validity was further supported by adapting established TAM/TPB items from prior studies in transport and technology adoption research.

As shown in

Figure 1, the two key factors in TAM are perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU), which are crucial for identifying the barriers to technology adoption and developing relevant strategies. In this study, the unit percentage (UP, %) was used to measure the degrees of PU and PEOU.

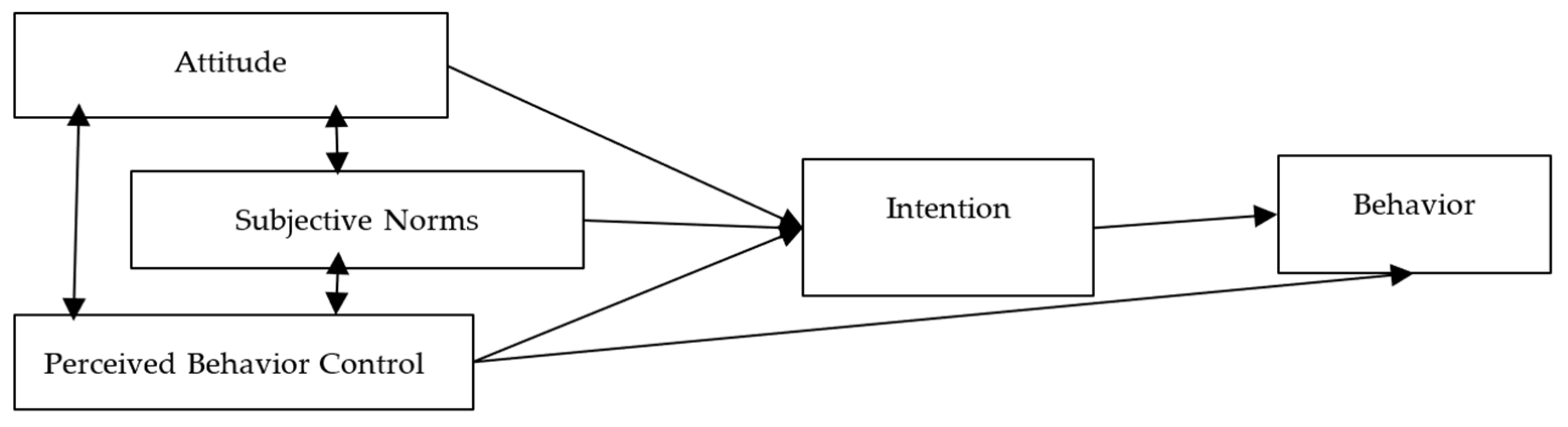

Additionally, TPB believes that people’s behavior can be predicted and has a strong relation to their attitudes (ATTs), subjective norms (SNs), and perceived behavior control (PBC) [

32].

Figure 2 shows a basic approach to using TPB.

To identify the sustainable use intentions of older passengers regarding digital air travel products and services, this study first identified and summarized their travel behavior patterns. The TAM was then used to assess their acceptance of digital air travel tools, proposing relevant strategies for air transport companies to address any acceptance barriers. Following this, a qualitative application of the TPB was employed to understand and identify behavioral intentions among older passengers. Finally, a prediction was made to forecast the likelihood of older passengers in China continuing to choose air travel, driven by the adoption of digital air travel tools.

3.5. Correlation and Regression Analysis

Goodwin and Leech [

34] highlight that correlation is a widely applied statistical method across various disciplines, particularly in research, to evaluate the effectiveness and reliability of studies. They emphasize that understanding simple correlation is crucial, as it forms the basis for grasping more advanced statistical techniques. Similarly, Taylor [

35] explains that correlation analysis is extensively utilized to identify relationships between two variables and assess the strength of these relationships, whether strong or weak. Mukaka [

36] notes that the choice of the correlation coefficient depends on the type of variables being analyzed. Xiao et al. [

37] describe correlation analysis as a data exploration method that reveals the degree of association between one dependent variable and multiple others in large datasets. They also outline three primary types of correlation coefficients: Pearson, Spearman, and Kendall. Taylor [

35] delves deeper into Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient, commonly referred to as RRR, which can indicate positive, negative, or no correlation. An RRR value close to ±1\pm 1 ± 1 denotes a strong linear relationship, while zero suggests no relationship. A positive correlation indicates that both variables increase together, whereas a negative correlation shows an inverse relationship. Mukaka [

36] further asserts that correlation coefficients cannot determine causation or establish dependent and independent variable relationships. They propose a “rule of thumb” for interpreting correlation coefficients based on a scale commonly cited in the research literature, helping to categorize the strength of correlations observed in the data (

Table 2).

According to Mukka [

36], a Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient is expressed as ϱ, which represents the population parameter, and r represents the sample statistics. The Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient is normally used when both variables, which are studied, are normally distributed. The Pearson coefficient is affected by extreme values, whereby there is a tendency for the strength of the relationship to be overestimated or to be weakened; hence, it is irrelevant when either or both variables are normally distributed. In order to calculate the correlation between the two variables

x and

y, the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient is represented by an equation as such:

Xiao et al. [

37] described the Pearson’s correlation coefficient equation, which was described by Mukka [

36], that the correlation coefficient r range must be between −1 and 1 so that it is able to determine the magnitude and direction of the relationship between a pair consisting of two variables [

36].

Regression analysis is a widely utilized method in market research, enabling researchers to examine the relationship between one independent variable and a dependent variable. This technique is commonly applied in various domains, such as marketing, where it can determine outcomes like sales performance. Compared to other analytical techniques, regression analysis offers superior insights by highlighting the significance of independent variables in relation to a dependent variable and facilitating predictive capabilities. Additionally, it allows for the comparison of variable effects across different scales, such as the impact of price changes [

38].

As this is an exploratory study, descriptive statistics were used to examine patterns. No inferential testing was conducted, which limits causal interpretation. Future research should employ methodological triangulation (e.g., interviews, focus groups) and rigorous statistical techniques (e.g., factor analysis, regression) to verify these findings. In addition, the unit percentage (UP, %) represents the proportion of respondents who selected each option and is used here as a simple descriptive indicator, and the future work should also replace this with validated scales and inferential modelling.

The results of this analysis offer clear guidelines for enhancing older passengers’ satisfaction with air travel, potentially encouraging their repeat air travel. Additionally, these outcomes provide the air transport industry with valuable insights for developing strategies that support sustainable travel for older passengers, contributing to both social and economic sustainability.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Passenger Travel Behavior Pattern and Technology Acceptance

Analyzing passengers’ travel behavior is a priority in the decision-making process of air transport companies [

39]. Passenger behavior and preferences are crucial drivers of improvement and growth in the air transport sector, significantly shaping the industry’s development trajectory. This section explores the relationship between older passengers’ travel behavior and their use of digital air travel tools, as well as their acceptance of these existing digital tools.

4.1.1. Flight Selection

Passengers’ travel behavior has a deep impact on the air transport industry’s strategy development and decision-making processes. Analyzing the primary factors influencing flight selection is the first step in understanding older passengers’ travel behavior, as illustrated in

Figure 3.

Airfare remains the primary factor influencing passengers’ flight selection. Over the past few decades, ticket prices have consistently been the most significant determinant of passengers’ flight choices [

40,

41,

42,

43], and older passengers are no exception. Other important factors, such as the number of flight stops, flight time and duration, airport location, and mode of land transport, are also highly ranked. It is from the seventh rank onward that these older passengers began to consider digital-related factors in their flight selection. Compared to traditional factors such as airfare and flight time, digital-related aspects, which account for approximately 17.0% of total responses, are not yet the primary influences on older passengers’ travel behavior in China. Among the digital-related factors, online check-in and digital passes are the most significant. These paperless services contribute to reducing waste within air transport, supporting the industry’s environmental sustainability efforts.

4.1.2. Pre-Airport Stage

This sub-section delves into the analysis of passengers’ travel behavior across different travel stages. Additionally, the analysis identifies the travel stages where digital factors have the most significant impact on older passengers in China.

Table 3 presents the behavior of older passengers when purchasing flight tickets, with respondents having the option to select more than one answer. If the percentage of responses favoring digital tools exceeds those preferring physical or manual channels, the ATT can be confirmed as positive.

Table 2 shows the flight ticketing behavior of older passengers, challenging the common belief that older individuals prefer physical stores for their bookings. Since the 1980s, the introduction of global distribution systems by air transport companies revolutionized the ticketing processes, with online ticketing becoming a key component in enhancing competitiveness and providing new experiences for passengers [

44]. In this context, online distribution systems are among the earliest digital services adopted globally in the air travel sector, including in China. Over the decades, as online distribution matured, a significant portion of young-old passengers in China now book their flight tickets through online platforms, as shown in

Table 2.

However, despite the prevalent use of online ticketing platforms among these passengers, understanding the reasons behind their choices is crucial for air transport companies looking to embrace digital transformation.

Table 3 presents the main reasons participants made their booking choices from the PEOU perspective, with respondents able to select more than one answer.

As shown in

Table 2, the number of young-old passengers who reported their ability to use online ticketing platforms during air travel ranked in first place.

Table 3 further reveals that the score of PEOU is 95.3. Respondents identified unfamiliarity with using online distribution platforms and concerns about their reliability as the main barriers to utilization. Among these, unfamiliarity with use is the most significant issue, affecting more than half of the respondents. Given that the majority of respondents were able to use online distribution platforms for booking flights,

Table 4 also highlights the perceived benefits of using digital ticketing platforms. This analysis exclusively considers responses pertaining to digital ticketing platforms, with participants allowed to select multiple answers.

Time saving and convenience are recognized as the most significant benefits of digital air travel tools, with UP scores of 74.9 and 75.9, respectively. Additionally, cost saving is ranked as the third most important benefit, with a UP score of 60.3. As shown in

Table 3, security also emerges as a key factor influencing older passengers in China to opt for digital platforms.

Other essential steps before passengers’ departure include checking flight and airport information.

Table 5 shows the results of how older passengers in China completed these activities, with more than one answer that could be selected for these questions.

It is evident that young-old passengers in China have a relatively high acceptance rate of using digital tools to support their air travel at the pre-airport stage. The number of respondents indicated that using digital tools to check flight and airport information ranked first place. Given that China is one of the world’s leading mobile markets, with 99.9% of users accessing the Internet and searching for information via their mobile phones [

45,

46], it is not surprising that digital tools have become the preferred choice for older passengers to check air travel-related information. According to

Table 6, the score of PEOU is 91.4. These responses highlighted that the main reasons limiting older passengers’ use of digital tools to check pre-airport information are uncertainty about the availability of these tools and unfamiliarity with their use. Similar to the findings in

Table 3, unfamiliarity with use is the predominant factor. Therefore, clearer instructions and increased advertisements provided by relevant air transport companies or travel agencies may further boost the number of older passengers using digital tools for air travel in this stage.

Table 6 also shows the benefits that respondents believed digital air travel tools offer in these travel stages. Only responses related to the use of digital tools are included in this analysis, and respondents could select more than one answer. The top two benefits that these older passengers identified with digital tools during the pre-airport stage are time saving and convenience, with UP scores of 75.1 and 72.2, respectively. Cost saving and security are also noted benefits, highlighting some of the key features of digital tools. Despite some responses indicating that these tools are difficult to use or lack adequate instructions, the number of such responses is relatively small. These issues can be addressed by improving the promotion of use and providing clearer guidance. Overall, the top benefits identified, which are time saving, convenience, and cost saving, underscore the advantages of digital travel tools. Consequently, older passengers’ ATTs towards using digital air travel tools in the pre-airport stage are largely positive, and their intention to use these tools in the future is relatively high.

4.1.3. Pre-Flight Stage

In the pre-airport stage, most digital air travel tools used by passengers are mobile phone based. Consequently, there may be differences between the TAM results for the pre-airport stage and the pre-flight stage, as this stage includes a greater variety of in-airport digital facilities rather than just mobile-phone-based tools.

Table 7 presents the results of passengers’ behavior in completing pre-flight activities. Participants could select more than one answer for each question.

Similar to the pre-airport stage, digital air travel tools maintained a relatively high score for checking travel-related information in this stage. However, the usage rates of these digital tools during flight check-in and boarding processes decline across all types of digital tools. There is an increase in the number of respondents using physical channels in this stage compared to the pre-airport stage. As shown in

Table 8, the score for PEOU drops to 88.6 at this travel stage. Additionally, unfamiliarity with use remains the primary reason limiting older passengers’ use of digital air travel tools.

Table 8 also highlights the PU of pre-flight digital air travel tools, which considers responses pertaining to digital air travel tools. Participants were allowed to select multiple answers. As shown in

Table 8, time saving and convenience remain the most significant perceived benefits identified by these older passengers, with both factors scoring above 70. Additionally, compared to

Table 6, the UP of cost saving has slightly decreased, while the UP of security has increased in this stage. Moreover, as many airports now recommend using automatic security check channels, the analysis of passengers’ ATTs and behavior related to security checks was included in TPB.

Table 9 presents respondents’ behavior during customs processes.

For respondents who have had an international trip before, 45.5% confirmed using manual counters for passport control during their overseas travels. Approximately 40% of respondents utilized automatic facilities for this process, while only 15% reported using mobile passport control Apps, which have not been widely implemented in many countries. Thus, approximately half of the respondents used digital tools for passport control activities. As shown in

Table 10, the score of PEOU continues to decline, dropping to 84. The primary factor limiting the use of digital air travel tools is increasingly identified as unfamiliarity of use, a trend attributed to more self-service facilities and fewer mobile Apps in airport activities.

Table 10 also shows the PU of digital air travel tools used in passport control processes. The analysis only considers responses related to using digital travel tools during travel, and participants were allowed to select more than one answer. As shown in

Table 10, the UP of time saving has increased by nearly 6 points compared to other in-airport activities. Digital tools significantly enhance efficiency and help passengers save time, addressing one of the key pain points of international air travel. Overall, the ATTs of young-old passengers towards digital air travel tools in this stage remains positive, with more than half expressing an intention to use these tools. However, the number of passengers finding it difficult to use digital tools has increased compared to the numbers in the pre-airport stage. To improve the experience, there is a need for more comprehensive user instructions and promotional efforts, particularly for self-service facilities at airports. Enhancing these aspects will help address the challenges older passengers face and improve their evaluation of digital air travel tools.

4.1.4. In-Flight and After-Flight Stages

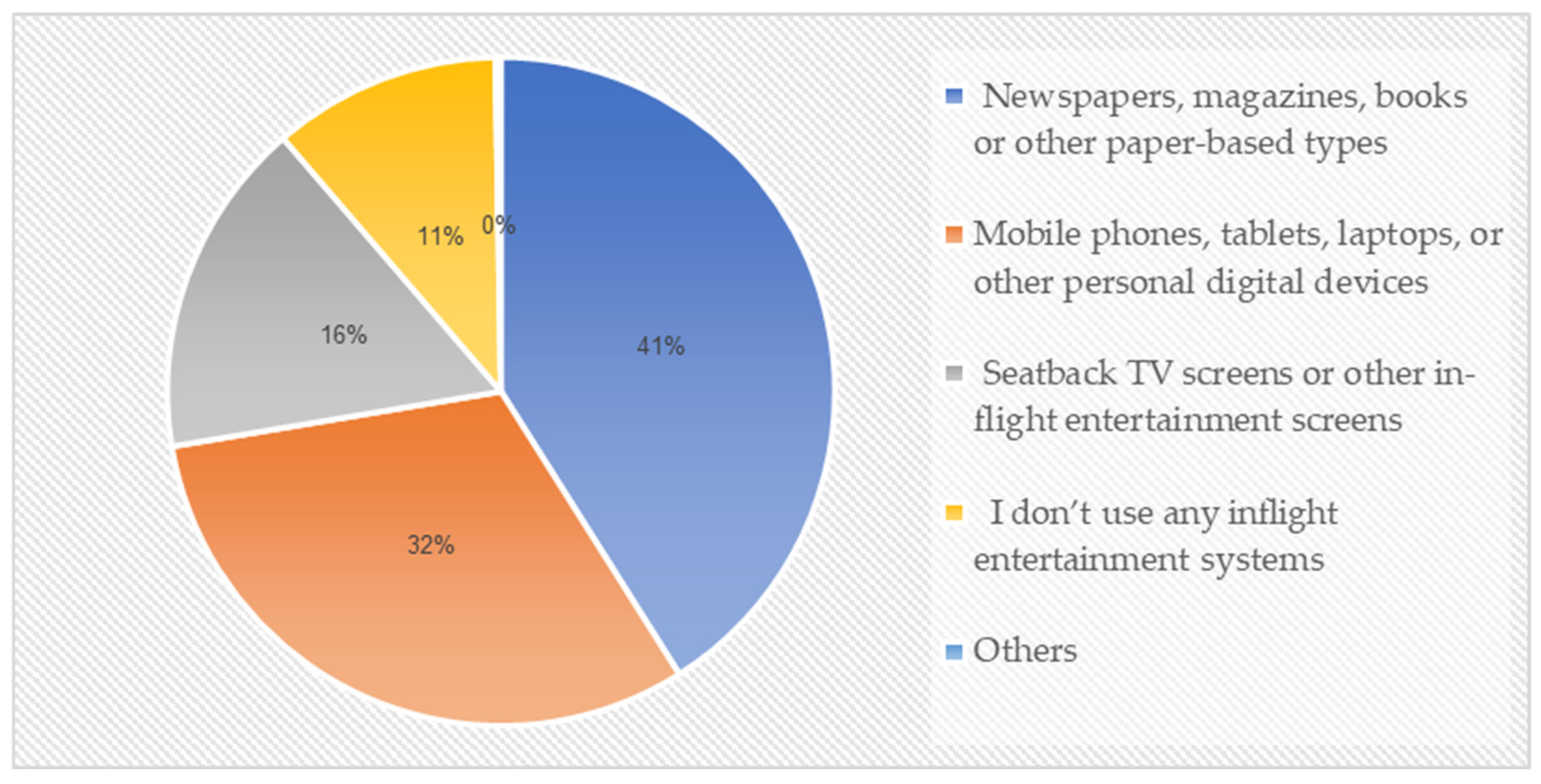

During the in-flight stage, the ATTs of older passengers towards in-flight entertainment was investigated, with respondents allowed to select multiple options. As shown in

Figure 4, the majority of older passengers preferred paper-based entertainment during their flights. Only 16% reported using seatback TV screens, and 11% did not use any in-flight entertainment systems. This indicates that the ATT towards in-flight entertainment is relatively low compared to other air travel activities and processes.

Table 11 shows the results of older passengers’ behavior in completing after-flight activities, especially focusing on the luggage claim process. Participants could select more than one answer for each question.

Most responses indicate that older passengers tend to use information display systems at airports to check luggage claim information, surpassing the use of digital air travel tools in this stage. Compared to earlier travel stages, the percentage of older passengers using digital tools for after-flight activities has decreased. In this stage, options related to using digital air travel tools are ranked second and third, respectively. Although ATTs towards these tools still can be confirmed as somewhat positive, the intention to use them is weaker compared to earlier stages of travel. Consequently, young-old passengers’ intentions regarding these choices are further analyzed and presented in

Table 12 and

Table 13.

It is evident that time saving and convenience remain the top two benefits of using digital air travel tools, with UPs of 84.8 and 70.9, respectively. However, the usage rate of these tools in the after-flight stage has decreased compared to the rates in the earlier stages. Therefore, there is a need to analyze why older passengers are less likely to use digital tools in this stage. As shown in

Table 13, many non-digital users found airport information display screens more convenient and time efficient. Additionally, some respondents expressed concerns about potential extra fees associated with digital tools, as they were unclear about fee structures in these tools. The primary issue appears still to be insufficient promotion of use and a lack of user instructions for digital tools. In

Table 12, the PEOU score is 86.4 in this stage. However, with a lower usage rate of digital tools in the after-flight stage, older passengers’ intention to use these tools is not as high as it is in other stages. Both unfamiliarity with use and uncertainty about availability may limit their use. To address this, developing more user-friendly and useful digital tools for the after-flight stage can enhance the acceptance rate and improve overall passenger experience.

4.1.5. After-Airport Stage

In the holistic air travel process, the after-airport stage is typically the final phase, involving land transport from the airport to the destination and after-service activities. Although this stage is sometimes not considered part of air travel in the conventional air travel process, it is crucial to investigate ATTs towards using digital air travel tools during this stage, as it directly impacts the passenger’s overall travel experience.

Figure 5 presents respondents’ attitudes towards using digital tools for land transport, which are related to their air trips, with respondents having the option to select multiple answers.

With the rapid development of mobile technology and government support, mobile car-sharing services are growing quickly and have become a significant trend in China [

47]. As indicated in

Figure 5, responses related to using digital methods to complete this activity constitute the majority, with only 16% of respondents opting for non-digital methods to check relevant land transport information. This outcome aligns with the current transport market trend in China, reflecting a positive ATT towards digital tools in this travel stage.

After-services represent another crucial aspect that influences passengers’ overall experiences, potentially affecting the reputation and even the viability of air transport companies.

Figure 6 shows responses about using digital channels for after-services, with participants allowed to select more than one answer for this question.

As shown in

Figure 6, the top three channels that respondents used to access after-services are Apps, phone calls, and official websites. Notably, only 1% of respondents had never used after-services before, and a mere 11% of responses were related to using non-digital channels to file complaints or obtain other after-services. This indicates that older passengers have a predominantly positive ATT towards using digital tools for after-services.

4.1.6. Overall Air Travel

In the previous sections, ATTs and TAM were employed to analyze older passengers’ travel behavior patterns and their acceptance of technology in air travel.

Figure 7 presents the respondents’ beliefs about which travel stages have been most deeply impacted by digital technologies, assessing and proving the accuracy and objectivity of the analysis in

Section 4.1.

Table 14 summarizes the results of ATTs and TAM from an overall perspective and should be analyzed in conjunction with

Figure 7.

Analyzing

Figure 7 and

Table 14 can help assess whether the analysis of passengers’ behavior and technology acceptance aligns with their perceptions of how digital technologies have influenced different travel stages. This holistic approach ensures that the conclusions drawn from the ATT and TAM analysis are well-supported.

Figure 7 shows that respondents believed the pre-airport and pre-flight travel stages were most deeply impacted by digital technologies and tools, which aligns with the ATT and PEOU results discussed in previous sub-sections. The percentages of respondents who selected the other three stages are significantly lower compared to those who chose the pre-airport and pre-flight stages. Interestingly, despite the high usage of digital tools for land transport activities, respondents felt that digital technology had the least impact on the after-airport stage.

As highlighted in

Table 14, the overall ATT is confirmed as generally positive. The average PEOU score of 89.14 indicates that most young-old passengers find current digital air travel tools easy to use. The top three benefits identified by respondents, which are time saving, convenience, and cost-saving, reflect the key features of digital tools. Consequently, older passengers, especially young-old passengers, in China show a positive intention to use digital air travel tools in future air trips, as evidenced by the above findings.

As older passengers value factors such as accessibility, user-friendliness, and convenience [

4,

5,

6], enhancing the development and promoting more user-friendly digital tools could further improve their satisfaction with air travel, thereby increasing their loyalty and likelihood of continuedly choosing air travel in the future. This, in turn, supports the sustainable air travel behavior of older passengers, which is crucial for helping air transport companies achieve social and economic sustainability development. Building on the results from the ATT and TAM analysis, the next section analyzes the collected data using TPB.

4.2. Applying TPB to Understand Older Passengers’ Air Travel Behavior

In qualitative TPB analysis, a hybrid deductive and inductive approach can be used. As per Zoellner et al. [

43], the deductive approach involves using TPB’s predefined coding constructs to analyze the data, while the inductive approach includes generating new themes or sub-themes from the meaning units (MUs). MUs are segments of text that convey a specific central meaning, serving as a fundamental element in qualitative analysis [

48]. In this study, meaning units were identified and coded by analyzing the relevant survey responses. The identified meaning units were then linked back to TPB’s predefined coding constructs, which are ATT, SN, and PBC. Finally, the total number of MUs was calculated and analyzed to generate the results of TPB.

Although the TPB analysis confirmed largely positive attitudes and strong intention to adopt digital tools, it is important to note that self-reported intention does not always translate into actual behavior. A small share of respondents (8%) stated they would prefer not to use digital tools in the future, despite reporting occasional current use. This gap may be explained by limited confidence, health concerns, or fear of technical issues. Future research could address this intention–behavior gap through longitudinal designs or observational methods (e.g., tracking actual tool usage across journeys) to strengthen the predictive validity of the TPB model in this context.

Table 15 shows the structure of the TPB analysis, including the themes and numbers of MUs. As respondents could select more than one answer to certain questions, the total number of MUs was counted based on the number of mentions.

4.2.1. ATT

As shown in

Table 14, more than half of respondents held a positive attitude towards using digital air travel tools, with the number of 819 MUs identified. The top three themes within these positive themes are time saving, convenience, and cost saving, which align with the TAM results. Additional positive themes include high-tech support (no. of MUs = 80), security and safety (no. of MUs = 73), and high accuracy of information (no. of MUs = 73). The theme of a less interrupted experience is mentioned the least, with only 18 MUs.

In addition to 55 MUs reflecting a neutral attitude, there are 450 MUs related to negative attitudes towards using digital air travel tools. The most frequently mentioned negative theme is uncertainty about available services, with 155 MUs. This is followed by a lack of user instructions (no. of MUs = 71) and inaccuracy of information (no. of MUs = 69). Non-functional features and additional costs incurred are the least mentioned negative themes, with 16 MUs and 15 MUs, respectively.

4.2.2. SN

Most respondents reported that they would use digital air travel tools due to airlines or airports promoting their use and suggestions, with 515 MUs reflecting this behavior. For example, as discussed in

Section 4.1, many airports are encouraging passengers to use automated security check channels. The majority of older passengers indicated that they would like to follow this recommendation and use the suggested relevant digital facilities. Only 72 MUs are related to not following airlines’ or airports’ recommendations. These respondents expressed concerns that, despite the recommendations, unfamiliarity with the tools and potential technical issues could lead to longer processing times. Additionally, some respondents indicated health-related concerns as a reason for not following the suggested use of digital air travel tools and facilities.

4.2.3. PBC

When respondents were asked what would make them confident and comfortable using digital air travel tools, the most frequently mentioned factor was the availability of useful and extra functions, with 257 MUs. A large portion of responses also highlighted the importance of clear and accurate information (no. of MUs = 197) and clear user instructions (no. of MUs = 194). Additionally, many respondents indicated that a passenger-centric design and strong personal information protection increased their confidence and ease of use with these digital tools and facilities. Moreover, 69 MUs are related to the availability of discounts as a contributing factor. Conversely, there are 83 MUs reflecting a lack of confidence or comfort with using digital air travel tools.

4.2.4. Intention

Most of these older passengers expressed a positive intention to use or continue using digital air travel tools in their trips. However, a small percentage of respondents (8.0%) indicated they would prefer not to use these tools in the future. These respondents believed that digital tools would be difficult to use and would complicate their air travel experience. On the other hand, most older passengers stated that their willingness to use digital air travel tools could be further enhanced by clearer user instructions and more accurate information provided.

The results of qualitative TPB analysis indicate that young-old passengers in China generally tend to use digital air travel tools, with most holding a positive attitude. Additionally, if air transport companies increase the promotion of use and provide clear recommendations, a majority of young-old passengers are likely to follow these suggestions and use relevant digital tools during their air travels. The top three factors that enhance older passengers’ confidence and ease of use are the availability of useful and extra functions (no. of MUs = 257), clear and accurate information (no. of MUs = 197), and clear user instructions (no. of MU = 194). These findings suggest that air transport companies can initially take actions on these aspects to encourage greater use of digital air travel tools among older passengers. By expanding the use of digital tools, air transport companies can achieve better aviation waste management through paperless services, reduce human errors, and enhance operational efficiency. Meanwhile, older passengers can enjoy fewer interruptions, greater convenience, and even lower travel costs. This mutual benefit contributes to more sustainable air travel for both air transport companies and older passengers in the future.

While most TPB studies rely on quantitative approaches, this study fills the gap between the analysis of passenger behavior and the use of qualitative TPB. Despite some limitations, such as sample size and age group distribution, the study provides strong evidence of the usefulness and effectiveness of qualitative TPB in the digital air travel domain. It offers valuable insights into the travel behavior of older passengers in a developing country like China. Future research could involve additional focus groups to further evaluate and validate the findings from this study.

4.3. The Result of Correlation and Regression Analysis

The Pearson correlation analysis of TAM and TPB constructs with behavioral intention (BI) reveals several important patterns that underscore the central role of perceived usefulness (PU) while also highlighting nuanced relationships among constructs (

Table 16).

The inferential analysis of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) constructs provides a more nuanced understanding of the determinants of behavioral intention (BI) to adopt digital applications in air travel among older passengers. The Pearson correlation analysis shows that perceived usefulness (PU) has the strongest direct association with BI (r = 0.161), indicating that the more passengers who recognize digital tools as beneficial, the more likely they are to intend to adopt them in future travel. Although modest in strength, this finding aligns with TAM theory, which posits usefulness as a central determinant of intention. Perceived ease of use (PEOU) demonstrated virtually no relationship with BI (r = 0.008), suggesting that ease of interaction with technology does not meaningfully influence adoption intentions in this demographic. This may reflect that once a baseline of digital literacy is achieved, the perceived benefits of the technology outweigh concerns about usability. Attitude (ATT) and perceived behavioral control (PBC) were also positively related to BI (r = 0.086 and r = 0.127, respectively), though these associations were weak, implying that more favorable evaluations of digital tools and a stronger sense of control are only minor contributors to intention in this context. More noteworthy were the intercorrelations among the independent constructs. PU correlated strongly with ATT (r = 0.546) and PBC (r = 0.578), while ATT and PBC also correlated highly with one another (r = 0.592). These relationships confirm that older passengers who perceive digital applications as useful are also more likely to evaluate them favorably and feel confident in their ability to use them. At the same time, PEOU displayed negative correlations with PU (r = −0.389), ATT (r = −0.309), and PBC (r = −0.258). This unexpected result may stem from the operationalization of PEOU in this study, which was based on reverse-coded negative experiences. It suggests that respondents who reported more difficulties with digital tools also tended to acknowledge their usefulness and maintain positive attitudes, which could reflect a subgroup of engaged but critical users or measurement artefacts requiring refinement in future studies.

The regression analysis further clarifies these relationships by modeling BI as a function of PU, PEOU, ATT, and PBC. Results reveal that PU is the only statistically significant predictor of BI (β ≈ 0.06, p ≈ 0.045), reinforcing its central role in explaining older passengers’ intentions. In contrast, PEOU (β ≈ 0.05, p = 0.22), ATT (β ≈ −0.006, p = 0.85), and PBC (β ≈ 0.027, p = 0.46) did not reach statistical significance. The regression intercept (≈3.43, p < 0.001) indicates that even without explanatory predictors, baseline BI is moderately high in this sample, reflecting a general openness to adopting digital tools. However, the overall explanatory power of the model is limited, with an adjusted R2 of approximately 0.03, meaning that the included constructs account for only approximately 3% of the variance in BI. While modest, this level of explanatory power is not uncommon in exploratory studies using single-item or count-based operationalization of constructs. The combination of correlation and regression results underscores that PU remains the dominant factor influencing adoption intentions, while ease of use, attitudes, and perceived control appear less impactful in this particular demographic and context. Taken together, these findings affirm the theoretical primacy of usefulness within TAM, highlight the importance of refining construct measurement for older passenger populations, and point to the need for richer models in future research that incorporate additional contextual and psychosocial variables to capture a broader spectrum of influences on digital adoption behavior.

4.4. Predicting Repeat Travel Behavior of Older Passengers

Based on

Section 4.1 and

Section 4.2, it is evident that young-old passengers in China have a generally positive attitude towards using digital air travel tools, with a strong intention to continue using these tools in the future. In this section, the digital impact on these passengers’ repeat travel behavior was analyzed, as shown in

Table 17.

As shown in

Table 17, over 80% of respondents confirmed that their continued choice of air travel would be positively influenced by the use of digital air travel tools. This positive evaluation aligns with the results of the TAM and TPB analyses. On the other hand, only 2.4% of respondents believed that digital air travel tools would not encourage them to choose air travel in the future, with some even indicating that the increased use of digital tools could reduce their willingness to travel by air. Additionally, approximately 16.4% of older passengers indicated that digital air travel tools would neither increase nor decrease their willingness to continue choosing air travel in the future. Therefore, the relationship between the use of digital air travel tools and older passengers’ repeat air travel behavior is identified as positive, with digital technology acting as a motivator for continued air travel among older passengers.

5. Conclusions and Limitations

This study focused on the “young-old” cohort (50–64 years) as they represent the majority of independently traveling older passengers in China and are more likely to engage with digital tools. However, this excludes the “old-old” group (65+), who often require personal assistance and may face stronger physical, cognitive, or digital barriers. This limitation may constrain the generalizability of our conclusions to the wider older population. Nearly 17% of respondents identified digital-related factors as their primary consideration when choosing flights. Among various digital services and products, online check-in and digital passes have been identified as the most significant ones. The overall ATTs of older passengers towards digital air travel tools has been confirmed as generally positive, despite some respondents expressing a neutral ATT during specific travel stages, such as the in-flight stage.

The average score for perceived ease of use is 89.14 across the entire travel process, with respondents showing greater confidence in using mobile-phone-based air travel tools. The top benefits identified included time savings, convenience, and cost savings. This indicates that older passengers, particularly young-old passengers in China, generally have a positive intention to use digital air travel tools. However, additional assistance may be required by some older passengers due to challenges like unfamiliarity with the tools and uncertainty about the availability of the tools during certain travel stages. Increased promotion of use and clear user instructions could serve as key drivers to enhance older passengers’ intention and willingness to use digital air travel tools.

Moreover, more than 60% of respondents confirmed a positive ATT in the TPB analysis, and approximately 5% held a neutral ATT. The top three themes identified in the TPB analysis, time saving, convenience, and cost saving, align with the PEOU results in the TAM analysis. Similar to the findings in TAM, the top negative themes identified in TPB are uncertainty of availability, lack of clarity in the process, and inaccuracy of information.

Additionally, over 87% of respondents indicated that they would be more likely to follow air transport companies’ recommendations to use digital air travel tools, highlighting the importance of promoting the use and assistance from these air transport companies again. Improved functions, clear and accurate information, and enhanced design have been identified as the top three factors that can increase older passengers’ confidence and comfort in using digital air travel tools in the future.

With continued improvements and targeted promotion of use, older passengers in China are likely to become increasingly willing to use digital air travel tools. Over 80% of respondents confirmed that digital technology influenced their continued choice of air travel, indicating that digital tools positively impact older passengers’ sustainable travel behavior. As more older passengers adopt digital tools, benefiting from time and cost savings, convenience, and an enhanced travel experience, their satisfaction towards air travel is predicted to increase. This, in turn, will generate long-term economic and social benefits for the air transport industry.

Furthermore, the growing number of digital users will contribute to a reduction in aviation waste and improved process efficiency, enhancing environmental sustainability in the air transport industry and society by improving waste management and reducing environmental impact. Thus, the digital impact not only enhances older passengers’ travel experiences but also strengthens the air transport industry’s viability. Ultimately, the sustainable travel behavior of passengers and the air transport industry’s sustainable operations will contribute to shared sustainability development, as illustrated in

Figure 8.

The inferential analyzes provided further evidence for the centrality of perceived usefulness in predicting older passengers’ digital adoption. Correlation results indicated that usefulness was most strongly, albeit modestly, associated with behavioral intention, while ease of use, attitude, and perceived control showed only weak relationships. Regression analysis confirmed perceived usefulness as the only statistically significant predictor of intention, highlighting that practical value rather than usability considerations primarily drives digital adoption in this demographic.

The results of this study filled the gap in research between older passengers’ air travel behavior and the impact of digital air travel tools. However, there are two limitations to consider. Firstly, the study primarily focused on young-old passengers, which limited the sample size and potentially narrowed the scope of the findings. Secondly, the study was conducted solely within the context of China, which restricts the generalizability of the results to other regions or populations.

To address these limitations, future research could involve a broader range of age groups to generate an understanding of digital air travel tool usage across different demographics. These findings are based on cross-sectional self-reported data, so causality cannot be inferred, and sustainable long-term behavior cannot be confirmed. Future longitudinal studies are recommended. Moreover, future research also should incorporate this older cohort using mixed methods (e.g., interviews, assisted surveys) to better capture their needs and to assess whether targeted interventions could support their digital adoption. Additionally, expanding the study to other national contexts would provide a more global understanding of older passengers’ sustainable digital air travel behavior.