Assessment of Infrastructure and Service Supply on Sustainable Urban Transport Systems in Delhi-NCR: Implications of Last-Mile Connectivity for Government Policies

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Research Motivation

1.3. Objectives

1.4. Research Questions

- RQ1: How do infrastructure and service delivery influence the effectiveness of SUTS in Delhi-NCR, particularly in relation to LMC?

- RQ2: What are the key infrastructural and service-related gaps that hinder seamless LMC to major public transit systems like the Delhi Metro Rail?

1.5. Significance of the Study

- Uncovering latent inefficiencies and inequities in current LMC systems.

- Providing empirical insights that can inform metro station area planning and TOD implementation.

- Supporting the design of inclusive, multimodal mobility solutions that address the needs of women and elderly, differently abled, and low-income populations.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Global Perceptions of LMC

2.2. Policy Framework for Transportation System for Indian Context

2.3. An Outline of LMC and SUTS Concept

2.4. Challenges and Barriers to LMC

- Ref. [134] investigated the integration of metro systems with e-rickshaw networks in Kolkata, finding that formalizing feeder services through licensing and designated stands reduced transfer times by 18% and improved commuter satisfaction scores by 0.4 points on a 5-point scale. The authors emphasize governance coordination between municipal authorities and metro corporations as a precondition for sustainable LMC.

- Ref. [135] developed a multi-criteria evaluation framework for LMC in Bengaluru, incorporating accessibility, intermodality, safety, and environmental impact. Using Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) weighting, they identified safety and reliability as the most influential factors for commuters, accounting for 42% of the total decision weight.

- Ref. [136] examined the performance of last-mile bicycle sharing programs integrated with the Delhi Metro. They found that stations with better protected cycling lanes and real-time bike availability information had 27% higher adoption rates compared to stations without such facilities. The study underlines the role of NMT infrastructure in enhancing LMC quality.

2.5. Analytical Approaches in LMC Research

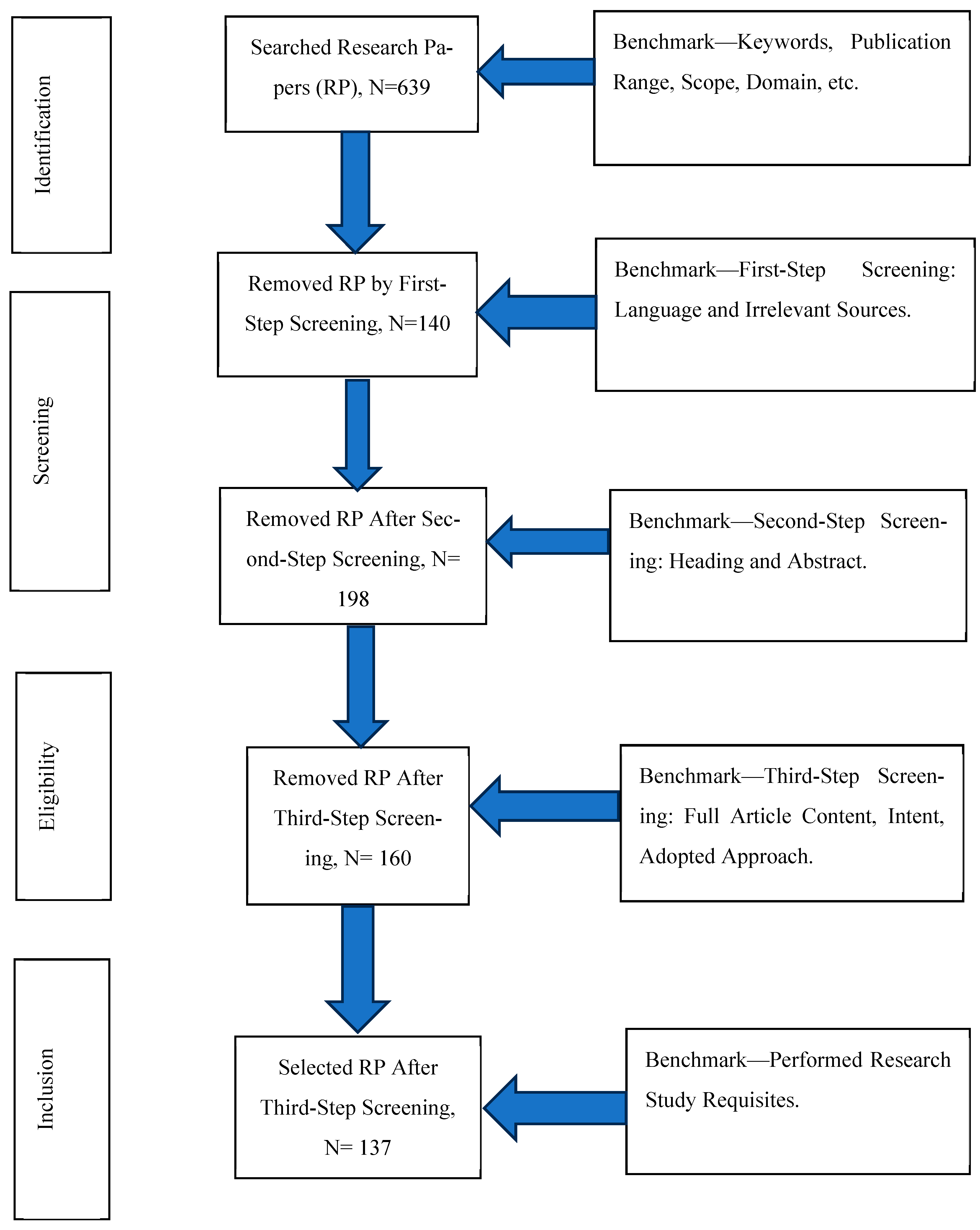

3. Research Methodology

Research Design

- A detailed understanding of spatial and infrastructural characteristics of LMC zones;

- Ground-level insights from public transport users;

- Evaluation of transport services and amenities using measurable indicators;

- Policy recommendations tailored to real-world conditions.

4. Case Study Approach

4.1. Data Collection Methods

4.1.1. Primary Data Collection

- (a)

- Demographic and Travel Characteristics of Respondents

- (b)

- Field Observation and Infrastructure Survey

4.1.2. Secondary Data Collection

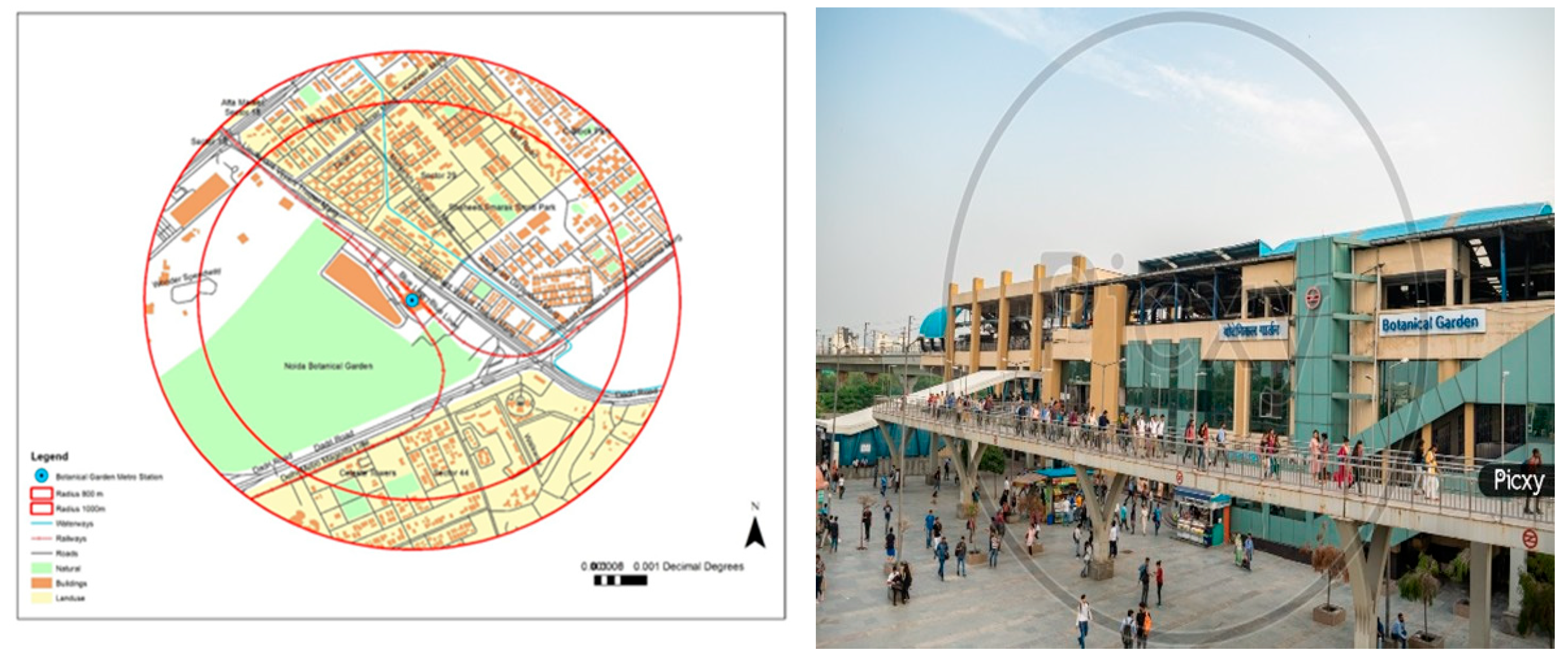

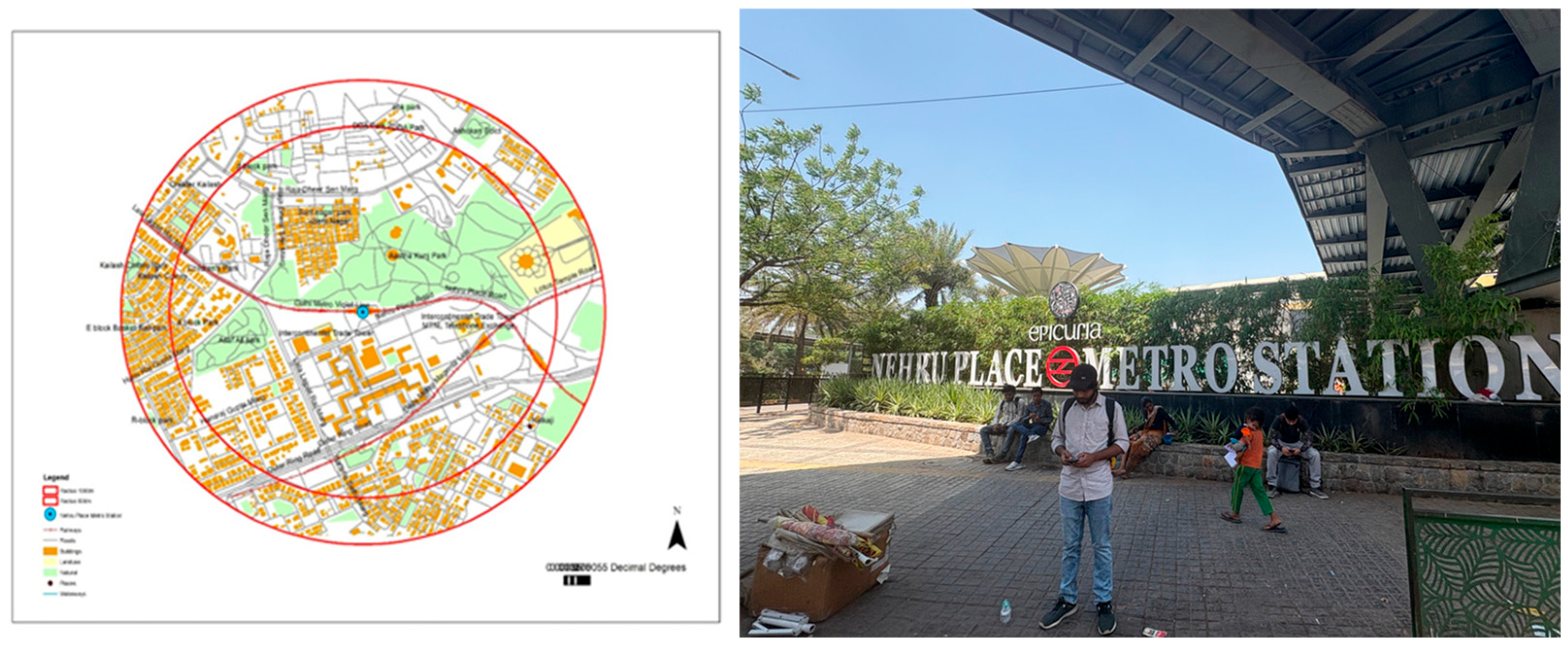

4.2. Spatial Analysis

4.3. Station-Wise Comparative Analysis

- (a)

- Thematic Analysis Descriptive—open-ended user responses and qualitative field observations were coded into recurring themes such as convenience, safety, affordability, and service reliability. This provided interpretative depth beyond quantitative metrics.

- (b)

- Descriptive Statistics—statistical summaries highlighted differences in demographic profiles, travel purposes, last-mile mode choices, and expenditure patterns across the two stations. Cross-tabulations and frequency distributions facilitated a nuanced understanding of user segments.

- (c)

- Infrastructure Scoring Matrix—a standardized scoring framework assessed station performance across multiple LMC indicators such as walkability, affordability, accessibility, safety, and integration. Results indicated that Nehru Place scored higher in IPT availability but lagged in pedestrian comfort, whereas Botanical Garden performed better in safety and infrastructure quality, based on the infrastructure scoring matrix using standardized indicators across five thematic pillars as represented in Table 3.

- (d)

- SWOT Analysis—a structured SWOT framework captured strategic strengths (e.g., high IPT availability), weaknesses (e.g., encroachment and bottlenecks), opportunities (e.g., app-based shared mobility), and threats (e.g., rising congestion) for each station represented in Table 4.

4.4. Comparative Statistical Analysis of LMC Indicators

4.4.1. Statistical Analysis (RP-01) of LMC Indicators for Nehru Place Metro Station

- The strong correlation between accessibility and inclusivity (0.90) confirms the design and infrastructure-driven inclusivity principle—stations with wide footpaths, ramps, and continuous pedestrian networks naturally enable gender-sensitive and accessible facilities.

- The weak correlations with intermodality (0.20) and service availability (0.25) indicates that physical access improvements alone do not guarantee operational integration. In other words, a well-designed approach to universal access must be complemented by systemic improvements in IPT integration and last-mile services.

- The moderate correlation with safety (0.35–0.40) suggests that safe, accessible routes encourage more walking and NMT adoption, but improvements in street lighting and CCTV are equally necessary to fully realize benefits.

4.4.2. Statistical Analysis (RP-01) of LMC Indicators for Botanical Garden Metro Station

- The extremely strong correlation between accessibility and inclusivity (0.95) reinforces the critical role of barrier-free infrastructure in promoting universal access. This indicates that improvements such as wide walkways, tactile paths, and ramps are highly linked to inclusive measures for differently abled users and gender-sensitive design.

- The weak correlation of accessibility with intermodality (0.15) and service availability (0.20) signals a clear disconnect between physical access and multimodal integration or service reliability. While users can access the station easily, their ability to seamlessly transfer to other modes (e-rickshaws, feeder buses, etc.) remains insufficient without better scheduling and wayfinding systems.

- The moderate correlation between service Availability and intermodality (0.40) suggests that improvements in feeder services and shared mobility options can significantly enhance multimodal connectivity. However, the low values across other pairs point toward systemic gaps.

- Safety shows only weak-to-moderate correlations with other indicators (0.25–0.30), indicating that current safety measures (lighting, surveillance, and public visibility) are not strongly aligned with accessibility or inclusivity improvements. To ensure last-mile adoption, safety interventions—such as woman-friendly IPT services and CCTV coverage—must complement physical access upgrades.

4.4.3. Statistical Analysis (RP-02) of LMC Indicators for Nehru Place Metro Station

- The strongest RP-02 correlation is with service availability (r = 0.40). A practical takeaway is that tightening operational reliability (predictable e-rickshaws/feeder buses, orderly pick-up bays, crowd management, etc.) can meaningfully lift perceived safety/comfort.

- Accessibility (r = 0.30) and intermodality (r = 0.35) exhibit complementary but secondary effects on safety: well-lit, obstruction-free footpaths and clearer interchange cues help people feel safer, yet operations still matter more.

- Inclusivity (r = 0.25) rises with safety but only weakly. Universal design upgrades (tactile paving, ramps, priority seating) should be advanced in parallel rather than be assumed to “ride along” with safety works.

4.4.4. Statistical Analysis (RP-02) of LMC Indicators for Botanical Garden Metro Station

- All RP-02 correlations are weak and positive (r = 0.20–0.30)—unlike Nehru Place, operational/service fixes by themselves are unlikely to move safety perceptions much.

- Accessibility’s correlation with inclusivity is very strong (r = 0.95), but accessibility/inclusivity were barely connected to intermodality/service (r = 0.15–0.25). In short, excellent infrastructure ≠ safe feeling when interchange/curbside spaces are chaotic.

- Uplifting safety at Botanical Garden likely hinges on qualitative environment controls (crowd management, enforcement, and surveillance coverage in high-conflict curb zones), not just “more service.”

4.4.5. Comparative Insights Across Stations

4.5. Ethical Considerations

- Respondents were informed about the purpose of the study and gave verbal consent before participating in the survey.

- Anonymity and confidentiality of user data were ensured.

- Sensitive questions (e.g., safety, harassment, etc.) were asked with caution and with an opt-out clause.

4.6. Research Limitations and Future Recommendations

5. Conclusions and Discussion

- Infrastructural Gaps: These include discontinuous or encroached footpaths, lack of pedestrian crossings, poor lighting, absence of universal access features (e.g., ramps for persons with disabilities), and insufficient signage for modal integration. At Nehru Place, the lack of gender-sensitive infrastructure significantly discouraged women from using public transit during non-peak hours.

- Service Gaps: Key deficiencies were found in unregulated IPT services, such as infrequent or unreliable feeder bus operations and lack of fare or schedule integration between the metro and last-mile modes. Furthermore, last-mile service availability after 9 PM was extremely limited at some locations, contributing to gendered mobility constraints.

- Governance and Institutional Barriers: Weak coordination among transport, urban planning, and municipal authorities further exacerbates the issue. Absence of centralized data sharing, fragmented service provision, and unclear responsibilities among agencies often delay or derail improvement efforts. These gaps collectively erode the user experience, reduce trust in public systems, and disproportionately affect vulnerable groups including women, the elderly, and low-income commuters.

5.1. Interpretation and Policy Recommendations

5.1.1. Accessibility (Indicator I)

- Prioritize continuous, obstacle-free pedestrian pathways and tactile guidance systems within 500–800 m catchment zones.

- Implement universal design standards in alignment with MoHUA’s TOD guidelines, including ramps, level crossings, and shade structures.

- Strengthen integration between metro access points and feeder nodes through clear, barrier-free pedestrian linkages.

5.1.2. Safety and Comfort (Indicator II)

- Conduct a station-area safety survey under frameworks like Safe Access to Transit.

- Install CCTV surveillance, panic buttons, and adequate lighting in IPT zones, pedestrian underpasses, and interchange points.

- Promote gender-sensitive design through clear sightlines, public seating, and informal surveillance via active street edges.

5.1.3. Intermodality (Indicator III)

- Establish dedicated IPT bays and micro-mobility zones within TOD influence areas to minimize conflicts between modes.

- Implement common mobility platforms for real-time scheduling and payment integration across metro, e-rickshaws, and feeder buses.

- Introduce wayfinding signage and interchange optimization to reduce transfer friction and improve user convenience.

5.1.4. Service Availability (Indicator IV)

- Deploy AI-based demand-responsive scheduling for IPT and feeder services to reduce waiting times during peak hours.

- Ensure 24 × 7 service coverage in high-demand corridors and provide real-time service alerts via digital platforms.

- Integrate feeder service performance indicators into metro operational dashboards for accountability.

5.1.5. Inclusivity (Indicator V)

- Enforce universal accessibility norms in all station precinct upgrades, including tactile paving, step-free access, and priority seating zones.

- Develop gender-responsive station plans incorporating well-lit, active, and socially monitored spaces.

- Integrate affordability measures, such as differential pricing for disadvantaged groups or last-mile subsidy schemes for low-income commuters.

5.1.6. Integrated Policy Outlook

- Universal Infrastructure Readiness: Mandatory inclusion of universal design and inclusive planning in TOD influence zones.

- Operational and Service Innovations: Dynamic fleet management, integrated ticketing, and safety-driven service standards.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Survey Questionnaire

- Section A: Accessibility (Indicator I)

| Indicator | Attributes/Statements | Strongly Disagree (1) | Disagree (2) | Neutral (3) | Agree (4) | Strongly Agree (5) |

| Footpath width and continuity | Footpaths are wide enough and continuous without breaks or obstructions. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Availability of ramps | Ramps are available and comply with standard gradient (1:12). | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Pedestrian crossings | Zebra crossings and signalized crossings are available and safe. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

- Section B: Safety And Comfort (Indicator II)

| Indicator | Attributes/Statements | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Street lighting | Adequate and functional street lighting is available at night. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Crowd management | Queuing systems and barriers effectively manage crowd during peak hours. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| CCTV surveillance | CCTV cameras are present and operational in key areas for safety. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

- Section C: Intermodality (Indicator III)

| Indicator | Attributes/Statements | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Integration with IPT | Intermediate Public Transport (auto, rickshaw, e-rickshaw) is easily accessible near station. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Signage clarity | Directional signage is clear, bilingual, and easy to follow. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Feeder bus connection quality | Feeder buses are frequent, punctual, and easily available during peak hours. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

- Section D: Service Availability (Indicator IV)

| Indicator | Attributes/Statements | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Frequency of last-mile services | Last-mile services are available at short intervals (minimal waiting time). | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Service coverage zones | Services cover a wide area, reaching most residential and commercial locations nearby. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Fare integration | Single/unified ticketing system for metro and last-mile services is available. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

- Section E: Inclusivity (Indicator V)

| Indicator | Attributes/Statements | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Gender-sensitive infrastructure | Separate waiting areas or women-only compartments/services are available. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Facilities for differently abled | Wheelchair-friendly paths and tactile flooring are provided for differently abled users. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Availability of seating areas | Adequate benches and shaded waiting spaces are provided for user convenience. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

Appendix B. Abbreviations

| S. No | Abbreviation | Description |

| 1. | LMC | Last-Mile Connectivity |

| 2. | NCR | National Capital Region |

| 3. | SUTS | Sustainable Urban Transport Systems |

| 4. | PTS | Public Transport Systems |

| 5. | BRT | Bus Rapid Transit |

| 6. | IPT | Intermediate Public Transport |

| 7. | TOD | Transit-Oriented Development |

| 8. | MoHUA | Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs |

| 9. | MRTS | Mass Rapid Transit Systems |

| 10. | PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis |

| 11. | RP | Research Papers |

| 12. | NUTP | National Urban Transport Policy |

| 13. | NMT | Non-Motorized Transport |

| 14. | ITS | Intelligent Transport Systems |

| 15. | XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

| 16. | DEA | Data Envelopment Analysis |

| 17. | GPS | Global Positioning System |

| 18. | GIS | Geographic Information System |

| 19. | QGIS | Quantum Geographic Information System |

| 20. | DTC | Delhi Transport Corporation |

| 21. | HUDA | Haryana Urban Development Authority |

| 22. | CCTV | Closed Circuit Television |

| 23. | WoS | Web of Science |

References

- Nations, U. World Urbanization Prospects; United Nations: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chandramauli, C. Census of India 2011: Provisional Population Totals: Urban Agglomerations and Cities; Retrieved September; Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner: New Delhi, India, 2011; Volume 7, p. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mogno, C.; Wallington, T.J.; Palmer, P.I.; Hakkim, H.; Sinha, B.; Sinha, V.; Steiner, A.L.; Sharma, S. Impact of electric and clean-fuel vehicles on future PM2. 5 and ozone pollution over Delhi. Environ. Res. Commun. 2024, 6, 075018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, D.; Huizenga, C. Implementation of sustainable urban transport in Latin America. Res. Transp. Econ. 2013, 40, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Harsha, V.; Subramanian, G.H. Evolution of urban transportation policies in India: A review and analysis. Transp. Dev. Econ. 2021, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K. Review of urban transportation in India. J. Public Transp. 2005, 8, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangiaracina, R.; Perego, A.; Seghezzi, A.; Tumino, A. Innovative solutions to increase last-mile delivery efficiency in B2C e-commerce: A literature review. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2019, 49, 901–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, C.M.; Bartels, S.A.; Purkey, E.; Neely, A.H.; Bisung, E.; Collier, A.; Dutton, S.; Aldersey, H.M.; Hoyt, K.; Kivland, C.L.; et al. Last mile research: A conceptual map. Glob. Health Action 2021, 14, 1893026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramulu, D.; Sankar, K.; Randhawa, A. Challenges of transit-oriented development (TOD) in Indian cities. Inst. Town Plan. India J. 2021, 18, 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, B.H.; Sidhu, B.K.; Kumari, N. Sustainable cities in India: A governance challenge. In International Yearbook of Soil Law and Policy 2018; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 27 February 2019; pp. 29–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ramji, A.; Venugopal, S. Creating a sustainable mobility ecosystem in India: Vision 2030. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference (ITEC-India), Bengaluru, India, 17–19 December 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gössling, S.; Neger, C.; Steiger, R.; Bell, R. Weather, climate change, and transport: A review. Nat. Hazards 2023, 118, 1341–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Advani, M.; Sharma, N.; Pandey, A. Vehicle Registration Dynamics in India Across the COVID-19 Timeline; IntechOpen: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Pellicelli, G.; Rossetti, S.; Caselli, B.; Zazzi, M. Urban regeneration as an opportunity to redesign Sustainable Mobility. Experi-ences from the Emilia-Romagna Regional Call. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 60, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, U.; Singh, A. Structural design and construction using energy analytical modelling for sustainability: A review. Int. J. Adv. Technol. Eng. Explor. 2024, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, F.; Comi, A. Providing dynamic route advice for urban goods vehicles: The learning process enhanced by the emerging technologies. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 62, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzarini, B.; Kollosche, I.; Roca, E.; Wybraniec, B.; Garola, À.; Ortiz, A.; Vidal, M. Creating a future that overcomes the digital divide through Scenario Building: Strategies for inclusive public transport in the Barcelona Metropolitan Area. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 1523–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranieri, S.; Duronio, F.; Villante, C.; D’Ovidio, G. Enabling technologies assessment for reducing Italian LPT emissions on short and long-term time frames. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 69, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, G.; Le Pira, M.; Inturri, G.; Ignaccolo, M.; Pluchino, A. A simulation-optimization approach to solve the first and last mile of mass rapid transit via feeder services. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 69, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaev, A.; Elkanova, E.; Malov, A.; Dzyuban, V.; Epkhiev, O.; Dudina, O.G.; Okhotnikov, I.; Pavlova, S. Sociological aspect of the city transport infrastructure management strategy. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 63, 2289–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisi, T.; Basbas, S.; Skoufas, A.; Kaltsidis, A.; Tesoriere, G. The impact of COVID-19 is not gender neutral: Regional scale changes in modal choices in Sicily. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 69, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiglione, M.; De Vincentis, R.; Nigro, M.; Rega, V. Bike Network Design: An approach based on micro-mobility geo-referenced data. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 62, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashant, A.; Dev, M. Modeling departure time choice of metro passengers: A case study of Delhi metro. Transp. Re-Search Procedia 2023, 72, 933–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korbee, D.; Naderer, G.; Fournier, G. The potential of automated minibuses in the socio-technical transformation of the transport system. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 2936–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.; Schmalz, U.; Cook, A.; Bolic, T.; Zareian, E.; Pilon, N.; Pérez, V.; Gendrot, C.; Laplace, I.; Arich, P. Future multimodal mobility scenarios within Europe. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 1869–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, Á. Lessons on transport equity from the CIVITAS ECCENTRIC project: Results in Madrid. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.C.; Dias, T.G. START: Sustainable transport awareness recommendation tool. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 4065–4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassar, E. Evaluating Mobility as a Service for sustainable travel among young adults. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 4159–4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, S.; Schildorfer, W.; Aigner, W.; Thonhofer, E.; Neubauer, M. How can a digital twin sustainably enhance integration and service quality for road authorities? Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 3909–3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisi, T.; Cocuzza, E.; Ignaccolo, M.; Inturri, G.; Tesoriere, G.; Canale, A. Detailing DRT users in Europe over the last twenty years: A literature overview. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 69, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoufas, A.; Campisi, T.; Basbas, S.; Tesoriere, G. Evaluation of the Perceived Pedestrian Level of Service in the post COVID-19 era: The case of Thessaloniki, Greece. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 69, 528–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fistola, R.; Gallo, M.; La Rocca, R.A. Micro-mobility in the “Virucity”. The Effectiveness of E-scooter Sharing. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 60, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šipuš, D.; Domeny, I.; Dolinayová, A.; Abramović, B. Equity fare system: Ranking of transport development criteria in integrated passenger transport. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 74, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, A.; Diana, M. Understanding micro-mobility usage patterns: A preliminary comparison between dockless bike sharing and e-scooters in the city of Turin (Italy). Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 62, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisi, T.; Ticali, D.; Ignaccolo, M.; Tesoriere, G.; Inturri, G.; Torrisi, V. Factors influencing the implementation and deployment of e-vehicles in small cities: A preliminary two-dimensional statistical study on user acceptance. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 62, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medved, D.; Blažinić, D.; Galijan, V.; Antolović, N. Evolution of data sources for integrated data-driven urban mobility man-agement. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 64, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubelíny, O.; Kubina, M.; Varmus, M. Building Smart Mobility in the City of Žilina. Transp. Res. Procedia 2024, 77, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruque, S.; Fonzone, A.; Fountas, G. Explaining expected non-shared and shared use of driverless cars in Edinburgh. Trans-Portation Res. Procedia 2022, 62, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šurdonja, S.; Otković, I.I.; Deluka-Tibljaš, A.; Campisi, T. Simplified model of children-pedestrian crossing speed at signalized crosswalks. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 69, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolarova, V.; Nobis, C.; Nägele, S. Towards a resilient and attractive future public transport: Insights from a study on public transport usage patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 2992–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawieska, J.; Archanowicz–Kudelska, K. Challenges behind sustainable schools commutes: Qualitative approach in the urban environment of XXIst century. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 2189–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipe, R.P.; Heath, A. Impacts of Implementing Mobility as a Service in Urban Areas—A Systematic Literature Review. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londoño, G.; Lozano, A. Universal accessibility and multimodal calm traffic on secondary streets to reduce pedestrian and vehicular conflicts. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 71, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsigdinos, S.; Paraskevopoulos, Y.; Tzouras, P.; Bakogiannis, E.; Vlastos, T. Rethinking road network hierarchy towards new accessibility perspectives. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 69, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgarra, V.; Meta, E.; Saporito, M.R.; Persia, L.; Usami, D.S. Improving sustainable mobility in university campuses: The case study of Sapienza University. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 60, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foltin, P.D.; Nagy, P.D.; Ondryhal, P.D. Using Big Data Analysis in increasing transportation infrastructure resilience. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 74, 1508–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinelli, M.; Gallo, M. An integrated bus transit service for demand-responsive urban public transport. Transp. Res. Procedia 2024, 78, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, A. Co-design of public spaces for pedestrian use and soft-mobility in the perspective of communities reappropriation and activation. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 60, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stępniak, M.; Gkoumas, K.; dos Santos, F.M.; Grosso, M.; Pekár, F. Recent trends and progress in public transport innovation in the scope of European research projects. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 4295–4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Tapia, M.; Sawady, T.; Alvarado, A.; Crespo, R.; Estrada, M.; Julio, B. Spatial allocation of polling places considering urban mobility applied to Santiago, Chile. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 71, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushakov, D.; Dudukalov, E.; Shmatko, L.; Shatila, K. Artificial Intelligence as a factor of public transportations system devel-opment. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 63, 2401–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, S.; Attard, M. Policies to promote cycling in Southern European island cities: Challenges and solutions from three ‘starter’cycling cities. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 60, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulgêncio, R.; Ferreira, M.C.; Abrantes, D.; Coimbra, M. Restart: A route planner to encourage the use of public transport services in a pandemic context. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 62, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokhan, S.; Nadeina, L.; Garov, S.; Sarandev, A. Public transport as a means of socialization of people with limited mobility. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 63, 1067–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivashova, V.; Chvalun, R.; Nadtochiy, Y.; Kalashova, A.; Surov, D. Assessing the satisfaction of residents with the work of public transport–regional experience. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 63, 1229–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yekimov, S.; Dosmuratova, E.; Chernyaev, A.; Meerson, A.; Korneeva, E.; Krayneva, R.; Nikitina, N.; Taskinbaikyzy, Z. The im-portance of the forecast of the number of inhabitants of the Czech Republic as a basis for the effective development of the transport industry. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 63, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.B.; Goyani, J.; Arkatkar, S.; Joshi, G. Modeling the effect of motorized two-wheelers and autorickshaws on crossing con-flicts at urban unsignalized T-intersections in India using surrogate safety measures. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 62, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cerrud, C.A.; de la Mota, I.F. Methodology for public passenger transport in developing countries: A survey. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 71, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augusto, P.M.; Santos, C.; Galvão, P. The Sustainable Mobility Model of Cascais. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 3933–3939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamcarz, P.; Droździel, P.; Gzik, A.; Rybicka, I.; Droździel, P. Characteristics of urban transport users and their level of satisfaction with transport services. A longitudinal study of passengers in Lublin city in 2018 and 2020. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 74, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnee, R.; Kroichvili, N.; Chrenko, D.; Kriesten, R. How Can Sustainable Business Models and Innovative Value Chains Ac-celerate the Transformation of Electric Vehicles? Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 70, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoulaki, M.; Christoforou, Z.; Gioldasis, C.; Roumeliotis, S. An experimental study on pedestrian movement in railway station. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 2526–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, R.; Monzón, A. Sustainable e-commerce urban distribution in LEZ areas: A greening Metro-based solution (M4G: Metro for Goods). Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 3363–3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.S.; Dev, M. Challenges of successful non-motorized transport infrastructure in Indian cities. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 1982–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusikka, T.; Eckhardt, J.; Hakkarainen, M. Moving beyond MaaS with ecosystemic way of work. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 1755–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelman, V.; Korchatov, A.; Carmel, R. Safety-related behaviours of e-cyclists on urban streets: An observational study in Israel. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 60, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetturi, D.; Tiboni, M.; Maternini, G.; Barabino, B.; Ventura, R. Kinematic performance of micro-mobility vehicles during braking: Experimental analysis and comparison between e-kick scooters and bikes. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 69, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazzini, M.; Lantieri, C.; Vignali, V.; Simone, A.; Dondi, G.; Luppino, G.; Grasso, D. Comparison between different territorial policies to support intermodality of public transport. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 60, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Prada, D.; Blanch-Fortuna, A.; Barrado-Rodrigo, J.A.; Vázquez-Seisdedos, L.; López-Santos, O.; El Aroudi, A.; Mar-tinez-Salamero, L. Electrical architecture for ultrafast charging station. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 70, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokhan, S.; Nadeina, L.; Eshiev, A.; Osmonov, O.; Musabayeva, K. Assessment of social and transport mobility for persons with severe impairments in urban environment. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 63, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.; Dubey, M. Interaction of public autonomous vehicles with stochastic driving modes on Indian roads. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 1824–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, R.N.; Mátrai, T. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in the demand for urban transportation in Budapest. Trans-Portation Res. Procedia 2022, 62, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, S.P.; de Sousa, J.P.; de Sousa, J.F. Designing urban mobility policies in a socio-technical transition context. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 62, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo, C.; Sgambati, S. Active mobility in historical centres: Towards an accessible and competitive city. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 60, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bartolomeo, S.; Caggiani, L.; Ottomanelli, M. An equity indicator for free-floating electric vehicle-sharing systems. Trans. Res. Procedia 2023, 69, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorko, G.; Neradilová, H.; Molnár, V.; Fabianová, J.; Michalik, P.; Linková, X. Analysis of the selected tram lines operation during the tram lines modernization project in the city of Košice-the case study. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 74, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghetti, F.; Longo, M.; Mazzoncini, R.; Somaschini, C. Preliminary evaluation of infrastructure and mobility services in mega-event: The Italian case study. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 69, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemardelé, C.; Baldó, A.; Aniculaesei, A.; Rausch, A.; Conill, M.; Everding, L.; Vietor, T.; Hegerhorst, T.; Henze, R.; Mátyus, L.; et al. The LogiSmile Project-Piloting Autonomous Vehicles for Last-Mile Logistics in European cities. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 71, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, M.; Borghetti, F.; Giuffrida, N.; Le Pira, M.; Longo, M.; Ignaccolo, M.; Inturri, G.; Maja, R. The” 15-minutes station”: A case study to evaluate the pedestrian accessibility of railway transport in Southern Italy. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 69, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquart, H.; Schicketanz, J. Experiences of safe and healthy walking and cycling in urban areas: The benefits of mobile methods for citizen-adapted urban planning. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 60, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yannis, G.; Oikonomou, M.; Papatzikou, E.; Petraki, V.; Chaziris, A.; Vlahogianni, E.; Papadakos, P. Traffic impacts of innovative traffic and parking arrangements in Athens, Greece. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 2487–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahti, J.; Heino, I.; Lusikka, T. The Concept of Urban Mobility Innovation Environment for Data-Driven Service Development. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 1792–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boo, E.; Sanvicente, E.; Ramos, É.M.; Chavardes, C.; Lombardi, D.; Gagliardi, G.; Hilmarcher, T. Understanding mobility profiles and e-kickscooter use in three urban case studies in Europe. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 3893–3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delponte, I.; Costa, V. Ligurian Internal Areas and Demand Responsive Transport: An innovative approach to tackle social exclusion and to re-design sustainable accessibility. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 69, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esztergár-Kiss, D.; Kerényi, T. Defining mobility packages by using city specific parameters and user groups: A case study. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 62, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, N.; Fazio, M.; Le Pira, M.; Inturri, G.; Ignaccolo, M. Connecting university facilities with railway transport stations: The case of Catania. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 60, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavory, S.S.; Trop, T.; Shiftan, Y. Sustainable self-organized ridesharing initiatives as learning opportunities. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 69, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajec, P.; Tuljak-Suban, D.; Slapnik, V. Micro-depots site selection for last-mile delivery, considering the needs of post-pandemic parcel recipients. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 69, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawood, E.N.; Fiorello, D.; Christidis, P. Mobility patterns after the pandemic: A survey in 20 European cities. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pribula, D.; Zitrický, V.; Kendra, M. Micromobility as a feeder for railway passenger transport. Transp. Res. Procedia 2024, 77, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candiani, M.; Malucelli, F.; Pascoal, M.; Schettini, T. Optimizing the integration of express bus services with micro-mobility: A case study. Transp. Res. Procedia 2024, 78, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhardt, M. Who is willing-to-pay for sustainable last mile innovations? Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 69, 910–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Ciommo, F.; Rondinella, G.; Foldesi, E.; Bánfi, M.G.; Giorgi, S.; Hueting, R.; Basu, S.; Delaere, H.; Keseru, I. When an Inclusive Universal Design Starts by the Data Collection Methods. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 2968–2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanne, M.; Twrdy, E.; Beškovnik, B. Sustainable transport solution in the coastal area in the framework of interurban mobility. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 2464–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryblia, M.; Boulinaki, E.; Tsoutsos, T. Assessment of Mobility Measures to Overcome Mobility Poverty and Orientate Towards Resilient Planning. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 1877–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedhoff, B.; Ramne, B.; Alias, C.; van Hassel, E.; Martens, S.E.; zum Felde, J.; Samuel, L. Elevating the logistics resilience of the Rhine-Alpine Corridor with the help of innovative vessel and cargo handling concepts. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 1998–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasopoulou, A.; Deijkers, T.; Ozkan, B.; Turetken, O. Exploring the Links of Mobility-as-a-Service Platform Functionalities. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 3672–3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioldasis, C.; Valero, Y.; Christoforou, Z. Modeling personal mobility device movement under mixed traffic conditions. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 3901–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radović, R.; Marasović, I.; Čačković, V.; Pleština, D.; Keresteny, D.; Anić, Z. The concept of a data aggregation platform in the function of a decision-making system for urban mobility management. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 64, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirdavani, A.; Muzyka, S.; Vandervoort, V.; Van Hoye, S. Application of building information modeling (BIM) for transportation infrastructure: A scoping review. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 73, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigro, M.; Castiglione, M.; Colasanti, F.M.; De Vincentis, R.; Liberto, C.; Valenti, G.; Comi, A. Investigating potential electric mi-cromobility demand in the city of Rome, Italy. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 62, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carboni, A.; Pirra, M.; Costa, M.; Kalakou, S. Active mobility perception from an intersectional perspective: Insights from two European cities. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 60, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boglietti, S.; Ghirardi, A.; Zanoni, C.T.; Ventura, R.; Barabino, B.; Maternini, G.; Vetturi, D. First experimental comparison between e-kick scooters and e-bike’s vibrational dynamics. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 62, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scerri, K.; Attard, M. Assessing perceptions of pedestrian-focused intervention in a car-dependent European island. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 69, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezgeta, D.; Čaušević, S.; Mehanović, M. Challenges of physical and digital integration TEN-T networks in Southeast European countries. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 64, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisi, T.; Tesoriere, G.; Skoufas, A.; Zeglis, D.; Andronis, C.; Basbas, S. Perceived pedestrian level of service: The case of Thes-saloniki, Greece. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 60, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, G.; Ribeiro, P.; Arsenio, E. Determinants of shared e-scooters usage in the city of Braga: Results from a mobility survey and trip data analysis. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 4002–4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromule, V.; Vilciņš, K.; Yatskiv, I.; Pēpulis, J. Digitalization in coach terminal: Riga case study. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 4223–4230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papas, T.; Basbas, S.; Campisi, T. Urban mobility evolution and the 15-minute city model: From holistic to bottom-up approach. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 69, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignaccolo, M.; Inturri, G.; Cocuzza, E.; Giuffrida, N.; Le Pira, M.; Torrisi, V. Developing micromobility in urban areas: Network planning criteria for e-scooters and electric micromobility devices. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 60, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, M.; Friedrich, B. Investigating spatial behaviour in different types of shared space. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 60, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballini, C.; Corazza, M.V.; Delponte, I. Turin, Rome and Genoa: Comparison of the level of maturity of three large Italian cities towards Mobility as a Service. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 69, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musolino, G.; Rindone, C.; Vitale, A.; Vitetta, A. Pilot survey of passengers’ preferences in mobility as a service (maas) scenarios: A case study. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 69, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venezia, E. Equity issues and road pricing tools: Empirical evidence. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 69, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caselli, B.; Carra, M.; Rossetti, S.; Zazzi, M. Exploring the 15-minute neighbourhoods. An evaluation based on the walkability performance to public facilities. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 60, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaix, C.; Di Ciommo, F. Workshop Synthesis: Understanding the mobility decision process: Revealing attitudes, motivations, and intentions. Transp. Res. Procedia 2024, 76, 644–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauer, A.; Dias, T.G.; de Sousa, J.P.; de Athayde Prata, B. Configurations and features of demand responsive transports. Transp. Res. Procedia 2024, 78, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmann, D.; Scharfe, R.; Trick, J.S.; Friedrich, B. Empirical Investigation of Dwell Times in Ridepooling Systems. Transp. Res. Procedia 2024, 78, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naborowski, C. Institutional work for sustainable mobility: Creating and disrupting practices, norms, and values in the case of Mobility as a service. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 3569–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarašūnienė, A.; Česnulaitis, D. The application of sustainable mobility and multimodality opportunities based on the example of Vilnius city. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 4366–4373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagiltseva, J.; Vasilenko, M.; Kuzina, E.; Drozdov, N.; Parkhomenko, R.; Prokopchuk, V.; Skichko, E.; Bagiryan, V. The economic efficiency justification of multimodal container transportation. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 63, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno-González, J.; Burrieza-Galán, J.; Cantú-Ros, O.G.; Livingston, C.; Penazzi, S.; Buire, C.; Marzuoli, A.; Delahaye, D. Air-rail timetable synchronisation for seamless multimodal passenger travel: A case study for Valencia-Lanzarote door-to-door Journeys. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 71, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushakov, D.; Dudukalov, E.; Mironenko, E.; Shatila, K. Big data analytics in smart cities’ transportation infrastructure modern-ization. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 63, 2385–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, A.; Smolokurov, E.; Bolshakov, R.; Parshin, V. Problems and prospects for the development of urban airmobility on the basis of unmanned transport systems. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 68, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurrì, S.; Santacaterina, E.; Guarrera, M.; Dalla Chiara, B. Driving modal shift on low-traffic railway lines through technological innovation: A case study in Piedmont (Italy) including hydrogen fuel-cells as an alternative. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 69, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkiya, E.; Maksimov, A.; Mamedov, A. Socio-cultural aspects of communicative interaction in the modern field of public urban transport. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 63, 2347–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dömény, I.; Dolinayová, A. Impact of Significant Discounts for Low-Income Groups of Passengers in Railway Transport on the Development of Transport Performances. Transp. Res. Procedia 2024, 77, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xenou, E.; Ayfantopoulou, G.; Giannaki, M.; Royo, B. SPROUT case studies: Assessing future mobility scenarios by following a city-led consequence analysis framework-the case of Budapest and Tel Aviv city. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khabarov, V.I.; Khabarova, O.G. Efficiency of labor resources use and issues of transport supply and demand development in large cities and agglomerations. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 61, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolgova, E.; Koroleva, E.; Bolgov, S. Smart transport in a smart city: European and Russian development management track. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 63, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yannis, G.; Chaziris, A. Transport system and infrastructure. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 60, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comi, A.; Sassano, M.; Valentini, A. Monitoring and controlling real-time bus services: A reinforcement learning procedure for eliminating bus bunching. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 62, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, N.; Molter, A.; Pilla, F.; Carroll, P. Feasibility of a simplified index to improve active mobility infrastructure based on digital survey: The case of Dublin. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 2309–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilahun, N.; Thakuriah, P.V.; Li, M.; Keita, Y. Transit use and the work commute: Analyzing the role of last mile issues. J. Transp. Geogr. 2016, 54, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Kathuria, A. Heterogeneity in passenger satisfaction of bus rapid transit system among age and gender groups: A PLS-SEM Multi-group analysis. Transp. Policy 2023, 141, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y. Development of a non-contact mobile screening center for infectious diseases: Effects of ventilation improvement on aerosol transmission prevention. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 87, 104232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewedairo, K.; Chhetri, P.; Jie, F. Estimating transportation network impedance to last-mile delivery: A Case Study of Maribyrnong City in Melbourne. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2018, 29, 110–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanuri, C.; Venkat, K.; Maiti, S.; Mulukutla, P. Leveraging innovation for last-mile connectivity to mass transit. Transp. Res. Procedia 2019, 41, 655–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, C.J. Measuring the quality of the first/last mile connection to public transport. Res. Transp. Econ. 2020, 83, 100949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snigdha Nangia, C.; Kumar, M. A review of attributes to reinventing public transport pertaining to urban mobility as sustainable solution. (2022). In Proceedings of the 9th Zero Energy Mass Custom Home International Conference, ZEMCH 2022, Bangalore, India, 3–5 November 2022; pp. 144–152. [Google Scholar]

- Snigdha Nangia, C.; Kumar, M. A Critical Review on Transitopia of Tomorrow as a Solution of the Transit System to Stimulate the Use of Public Transportation to Make Cities Liveable. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Trends and Recent Advances in Civil Engineering, Noida, India, 20–21 August 2022; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 303–314. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Category | Botanical Garden (Nos.) | Nehru Place (Nos.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 208 | 200 |

| Female | 177 | 185 | |

| Age Group | 18–24 years | 108 | 96 |

| 25–34 years | 138 | 147 | |

| 35–44 years | 77 | 85 | |

| 45+ years | 62 | 57 | |

| Occupation | Student | 85 | 69 |

| Service/Job | 162 | 169 | |

| Business/Self-employed | 77 | 85 | |

| Homemaker/Other | 61 | 62 | |

| Monthly Household Income | <₹25,000 | 77 | 69 |

| ₹25,000–₹50,000 | 131 | 135 | |

| ₹50,000–₹75,000 | 100 | 108 | |

| >₹75,000 | 77 | 73 | |

| Travel Purpose | Work/Business | 177 | 185 |

| Education | 69 | 61 | |

| Leisure/Shopping | 100 | 108 | |

| Other | 39 | 31 | |

| Usual Last-Mile Mode | E-rickshaw | 135 | 135 |

| Auto-rickshaw | 100 | 100 | |

| Walk | 77 | 77 | |

| Cycle/Bike | 38 | 38 | |

| Public Bus | 35 | 35 |

| Nehru Place TOD Zone | Botanical Garden TOD Zone | |

|---|---|---|

| Location/Metro Line | Violet Line (Line 6), Nehru Place, South Delhi. | Blue Line (Line 3) which connects Dwarka in Delhi to Noida City Centre in Noida. |

| Connectivity | Nehru Place metro station connects two or more different metro lines, allowing passengers to transfer between them. | Botanical metro station serves as an important transportation hub, connecting Noida with other parts of Delhi and the NCR. |

| Station Typology | Nehru Place metro Serves as an interchange station in Delhi Metro, as an interchange point between the Violet Line (Line 6) and the Magenta Line (Line 8) of the Delhi Metro network. | Botanical metro station also serves as an interchange station with the Aqua Line of the Noida Metro. This interchange allows passengers to switch between the Blue Line and the Aqua Line, enhancing connectivity within Noida. |

| Land Use | Nehru Place metro station is surrounded by a major commercial and business center in Delhi. The area is known for its IT markets, shopping complexes, and office spaces. | Botanical metro station is surrounded by residential areas, commercial complexes, educational institutions, and parks. It serves as a convenient transportation option for people living or working in the vicinity. |

| Catchment Area/TOD ZONE |  |  |

| Parameter | Indicator | Nehru Place (5) | Botanical Garden Score (5) | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accessibility (Indicator I) | Footpath width and continuity | 4.2 | 4.5 | 4.35 |

| Availability of ramps | 4.0 | 4.4 | 4.20 | |

| Pedestrian crossings | 4.1 | 4.3 | 4.20 | |

| Inclusivity (Indicator II) | Gender-sensitive infrastructure | 2.3 | 2.8 | 2.55 |

| Facilities for differently abled | 2.0 | 2.6 | 2.30 | |

| Availability of seating/waiting areas | 1.9 | 2.5 | 2.20 | |

| Safety and Comfort (Indicator III) | Street lighting | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.65 |

| Crowd management | 2.2 | 2.9 | 2.55 | |

| CCTV surveillance | 2.0 | 2.6 | 2.30 | |

| Intermodality (Indicator IV) | Integration with IPT | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.25 |

| Signage clarity | 2.1 | 2.4 | 2.25 | |

| Feeder bus connection quality | 1.8 | 2.2 | 2.00 | |

| Service Availability (Indicator V) | Frequency of last-mile services | 4.0 | 4.3 | 4.15 |

| Service coverage zones | 4.1 | 4.4 | 4.25 | |

| Fare integration | 4.0 | 4.2 | 4.10 |

| Metro Station | Nehru Place | Botanical Garden |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths | Proximity to commercial hub, good IPT presence | Strong intermodal integration, wider walkways, active CCTV, TOD surroundings |

| Weaknesses | Poor lighting, weak universal access, gender-insensitive design, crowding | Fare affordability issues, lack of shaded walkways in certain zones |

| Opportunities | Smart redesign of footpaths; integrated fare systems; female safety audits | MaaS platforms, expanded feeder coverage |

| Threats | Unchecked encroachment, user shift to private modes | Overcrowding due to TOD growth; pricing barriers for low-income groups |

| (a) | |||||

| Accessibility Indicator I | Safety and Comfort Indicator II | Intermodality Indicator III | Service Availability Indicator IV | Inclusivity Indicator V | |

| Accessibility Indicator I | 1 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.90 |

| Safety and Comfort Indicator II | 0.30 | 1 | 0.35 | 0.40 | 0.25 |

| Intermodality Indicator III | 0.20 | 0.35 | 1 | 0.45 | 0.20 |

| Service Availability Indicator IV | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.45 | 1 | 0.30 |

| Inclusivity Indicator V | 0.90 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 1 |

| (b) | |||||

| Accessibility Indicator I | Safety and Comfort Indicator II | Intermodality Indicator III | Service Availability Indicator IV | Inclusivity Indicator V | |

| Accessibility Indicator I | 1 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.95 |

| Safety and Comfort Indicator II | 0.25 | 1 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.20 |

| Intermodality Indicator III | 0.15 | 0.30 | 1 | 0.40 | 0.15 |

| Service Availability Indicator IV | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.40 | 1 | 0.25 |

| Inclusivity Indicator V | 0.95 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choudhary, S.; Singh, D.P.; Kumar, M. Assessment of Infrastructure and Service Supply on Sustainable Urban Transport Systems in Delhi-NCR: Implications of Last-Mile Connectivity for Government Policies. Future Transp. 2025, 5, 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040134

Choudhary S, Singh DP, Kumar M. Assessment of Infrastructure and Service Supply on Sustainable Urban Transport Systems in Delhi-NCR: Implications of Last-Mile Connectivity for Government Policies. Future Transportation. 2025; 5(4):134. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040134

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoudhary, Snigdha, D. P. Singh, and Manoj Kumar. 2025. "Assessment of Infrastructure and Service Supply on Sustainable Urban Transport Systems in Delhi-NCR: Implications of Last-Mile Connectivity for Government Policies" Future Transportation 5, no. 4: 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040134

APA StyleChoudhary, S., Singh, D. P., & Kumar, M. (2025). Assessment of Infrastructure and Service Supply on Sustainable Urban Transport Systems in Delhi-NCR: Implications of Last-Mile Connectivity for Government Policies. Future Transportation, 5(4), 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040134