Micro-Mobility Safety Assessment: Analyzing Factors Influencing the Micro-Mobility Injuries in Michigan by Mining Crash Reports

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Crash Data

2.2. Crash Diagrams Preprocessing

2.3. K-Fold Cross-Validation

2.4. AlexNet CNN Architecture

2.5. Micro-Mobility Crash Variables

2.6. Random Forest (RF)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. AlexNet CNN Model Configuration and Performance Metrics

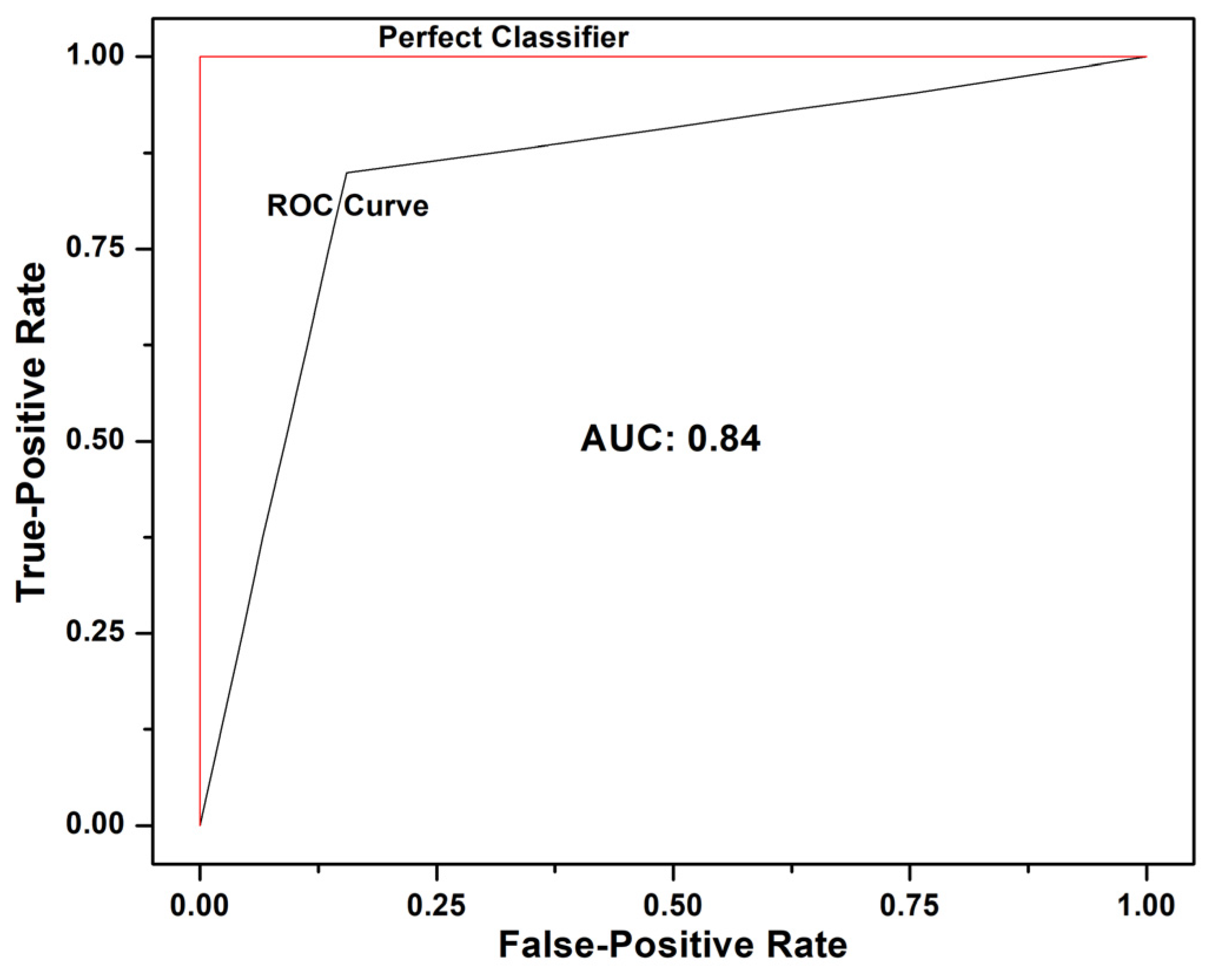

3.2. RF Model Configuration and Validation

3.3. Decision Rules from the RF Model

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pérez-Zuriaga, A.M.; Dols, J.; Nespereira, M.; Garcia, A.; Sajurjo-de-No, A. Analysis of the consequences of car to micromobility user side impact crashes. J. Saf. Res. 2023, 87, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Du, B.; Zheng, Z.; Shen, J. Space sharing between pedestrians and micro-mobility vehicles: A systematic review. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2023, 116, 103629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferenchak, N.N.; Marshall, W.E. Traffic safety for all road users: A paired comparison study of small & mid-sized US cities with high/low bicycling rates. J. Cycl. Micromobil. Res. 2024, 2, 100010. [Google Scholar]

- Jaber, A.; Csonka, B. Towards a sustainable and safe future: Mapping bike accidents in urbanized context. Safety 2023, 9, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, P.; Berloco, N.; Coropulis, S.; Intini, P.; Ranieri, V. Analysis of E-Scooter Crashes in the City of Bari. Infrastructures 2024, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, J.; Niska, A.; Forsman, Å. Injured cyclists with focus on single-bicycle crashes and differences in injury severity in Sweden. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2022, 165, 106510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anke, J.; Ringhand, M.; Petzoldt, T.; Gehlert, T. Micro-mobility and road safety: Why do e-scooter riders use the sidewalk? Evidence from a German field study. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2023, 15, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Zhang, X. Injury severity analysis of single-vehicle and two-vehicle crashes with electric scooters: A random parameters approach with heterogeneity in means and variances. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 195, 107408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C.; Ackerman, E.; Fan, B.; Bigham, J.; Carrington, P.; Fox, S. Accessibility and the crowded sidewalk: Micromobility’s impact on public space. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference, Virtual, 28 June–2 July 2021; pp. 365–380. [Google Scholar]

- Goralzik, A.; König, A.; Alčiauskaitė, L.; Hatzakis, T. Shared mobility services: An accessibility assessment from the perspective of people with disabilities. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2022, 14, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Ma, Q.; Wang, Z.; Cai, Q.; Xie, K.; Yang, D. Safety of micro-mobility: Analysis of E-Scooter crashes by mining news reports. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2020, 143, 105608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Green, E.; Chen, M.; Souleyrette, R.R. Identifying secondary crashes using text mining techniques. J. Transp. Saf. Secur. 2020, 12, 1338–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwayu, K.M.; Kwigizile, V.; Lee, K.; Oh, J.-S. Discovering latent themes in traffic fatal crash narratives using text mining analytics and network topology. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 150, 105899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qawasmeh, B.; Oh, J.S.; Kwigizile, V.; Qawasmeh, D.; Al Tawil, A.; Aldalqamouni, A. Analyzing Daytime/Nighttime Pedestrian Crash Patterns in Michigan Using Unsupervised Machine Learning Techniques and their Potential as a Decision-Making Tool. Open Transpl. J. 2024, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, A.; Ariff, N.M.; Bakar, M.A.A.; Roslan, A. Classification of driver injury severity for accidents involving heavy vehicles with decision tree and random forest. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, M.; Lan, L.; Zahid, M.; Jamal, A. A comparative study of machine learning classifiers for injury severity prediction of crashes involving three-wheeled motorized rickshaw. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 154, 106094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Chen, H.; Zhang, G.; Wang, X. Deep learning-based applications for safety management in the AEC industry: A review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, M.; Aguado, A. Feature Extraction and Image Processing for Computer Vision; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- O’Mahony, N.; Campbell, S.; Carvalho, A.; Harapanahalli, S.; Hernandez, G.V.; Krpalkova, L.; Riordan, D.; Walsh, J. Deep learning vs. traditional computer vision. In Advances in Computer Vision: Proceedings of the 2019 Computer Vision Conference (CVC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 25–26 April 2019, Volume 11; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 128–144. [Google Scholar]

- Alzubaidi, L.; Zhang, J.; Humaidi, A.J.; Al-Dujaili, A.; Duan, Y.; Al-Shamma, O.; Santamaría, J.; Fadhel, M.A.; Al-Amidie, M.; Farhan, L. Review of deep learning: Concepts, CNN architectures, challenges, applications, future directions. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 1–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.-W.; Zhang, J. Feature extraction and image retrieval based on AlexNet. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Digital Image Processing (ICDIP 2016), Chengu, China, 20–22 May 2016; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2016; pp. 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- MTCF. Michigan Traffic Crash Facts (MTCF). Available online: https://www.michigantrafficcrashfacts.org/ (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Calhoun, B.C.; Uselman, H.; Olle, E.W. Development of Artificial Intelligence Image Classification Models for Determination of Umbilical Cord Vascular Anomalies. J. Ultrasound Med. 2024, 43, 881–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qawasmeh, B.S. Safety Assessment for Vulnerable Road Users Using Automated Data Extraction with Machine-Learning Techniques. Ph.D. Thesis, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Samir, S.; Emary, E.; El-Sayed, K.; Onsi, H. Optimization of a pre-trained AlexNet model for detecting and localizing image forgeries. Information 2020, 11, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, A.; Kornblith, S.; Schmidt, L. Does progress on ImageNet transfer to real-world datasets? Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C.; Yang, J.J. Effectiveness of resampling methods in coping with imbalanced crash data: Crash type analysis and predictive modeling. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 159, 106240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skryjomski, P.; Krawczyk, B. Influence of minority class instance types on SMOTE imbalanced data oversampling. In First International Workshop on Learning with Imbalanced Domains: Theory and Applications; Pmlr: Skopje, Macedonia, 2017; pp. 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Boateng, E.Y.; Otoo, J.; Abaye, D.A. Basic tenets of classification algorithms K-nearest-neighbor, support vector machine, random forest and neural network: A review. J. Data Anal. Inf. Process. 2020, 8, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, S.; Sahin, E.K. Comparison of tree-based machine learning algorithms for predicting liquefaction potential using canonical correlation forest, rotation forest, and random forest based on CPT data. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2022, 154, 107130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.M.; Cliff, A.; Romero, J.; Shah, M.B.; Jones, P.; Gazolla, J.G.F.M.; A Jacobson, D.; Kainer, D. Evaluating the performance of random forest and iterative random forest based methods when applied to gene expression data. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 3372–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonlau, M.; Zou, R.Y. The random forest algorithm for statistical learning. Stata J. 2020, 20, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaggle. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com (accessed on 8 June 2024).

- Wang, S.-H.; Xie, S.; Chen, X.; Guttery, D.S.; Tang, C.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y.-D. Alcoholism identification based on an AlexNet transfer learning model. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 454348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaiarasi, P.; Rani, P.E. A comparative analysis of AlexNet and GoogLeNet with a simple DCNN for face recognition. In Advances in Smart System Technologies: Select Proceedings of ICFSST 2019; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 655–668. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, I.; Goyal, G.; Chandel, A. AlexNet architecture based convolutional neural network for toxic comments classification. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 34, 7547–7558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Tawil, A.; Almazaydeh, L.; Qawasmeh, D.; Qawasmeh, B.; Alshinwan, M.; Elleithy, K. Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Algorithms for Email Phishing Detection Using TF-IDF, Word2Vec, and BERT. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2024, 81, 3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardalaç, F.; Akmal, H.; Ayturan, K.; Acharya, U.R.; Tan, R.-S. Fetal Status Classification Based on Feature Elimination and Hyperparameter Optimization Using Cardiotocographic Data. SSRN 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mali, N.; Restrepo, F.; Abrahams, A.; Ractham, P. Implementation of mars metrics and Mars charts for evaluating classifier exclusivity: The comparative uniqueness of binary classifier predictions. Softw. Impacts 2022, 12, 100259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muppalaneni, N.B.; Ma, M.; Gurumoorthy, S.; Kannan, R.; Vasanthi, V. Machine learning algorithms with ROC curve for predicting and diagnosing the heart disease. In Soft Computing and Medical Bioinformatics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Nembrini, S.; König, I.R.; Wright, M.N. The revival of the Gini importance? Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3711–3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houten, R.V.; Kwigizile, V.; Oh, J.S.; Mwende, S.; Qawasmeh, B. Effective Pedestrian/Non-Motorized Crossing Enhancements Along Higher Speed Corridors; No. SPR-1734; Michigan. Dept. of Transportation, Research Administration: Lansing, MI, USA, 2023.

- Prati, G.; Pietrantoni, L.; Fraboni, F. Using data mining techniques to predict the severity of bicycle crashes. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2017, 101, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Yu, J.; Chen, Y.; Ma, C.; Ye, X.; Chen, J. Factors associated with the severity of motor vehicle crashes involving electric motorcycles and electric bicycles: A random parameters logit approach with heterogeneity in means. Transp. Res. Rec. 2023, 2677, 691–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yitzhak Acosta-Carrascal, H. Gender-Based Motivations for Usage and Avoidance of Shared Micro-Mobility During Night-Time in Stockholm, Sweden. Master’s Thesis, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, 2023. Available online: https://diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1825417&dswid=-5395 (accessed on 8 June 2024).

- Karpinski, E.; Bayles, E.; Sanders, T. Safety analysis for micromobility: Recommendations on risk metrics and data collection. Transp. Res. Rec. 2022, 2676, 420–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Layer Type | Output Shape | Number of Filters | Kernel Size | Stride |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input | 227 × 227 × 3 | - | - | - |

| Convolutional 1 | 55 × 55 × 96 | 96 | 11 × 11 | 4 |

| Max Pooling 1 | 27 × 27 × 96 | - | 3 × 3 | 2 |

| Convolutional 2 | 27 × 27 × 256 | 256 | 5 × 5 | 1 |

| Max Pooling 2 | 13 × 13 × 256 | - | 3 × 3 | 2 |

| Convolutional 3 | 13 × 13 × 384 | 384 | 3 × 3 | 1 |

| Convolutional 4 | 13 × 13 × 384 | 384 | 3 × 3 | 1 |

| Convolutional 5 | 13 × 13 × 256 | 256 | 3 × 3 | 1 |

| Max Pooling 3 | 6 × 6 × 256 | - | 3 × 3 | 2 |

| Fully Connected 1 | 4096 | - | - | - |

| Fully Connected 2 | 4096 | - | - | - |

| Fully Connected 3 | 1000 | - | - | - |

| Variables | Variables Code | Values | Fatal/Serious Injury | Minor/No Injury | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Crash Characteristics | Weekend | Weekend | 1 = Weekend | 213 | 239 | 452 |

| 2 = Weekday | 329 | 393 | 722 | |||

| Intersection | Intersection | 1 = Intersection | 329 | 432 | 761 | |

| 2 = Midblock | 213 | 200 | 413 | |||

| Wet Pavement | WetPav | 1 = Yes | 59 | 81 | 140 | |

| 2 = No | 483 | 551 | 1034 | |||

| Nighttime | Nighttime | 1 = Yes | 140 | 164 | 304 | |

| 2 = No | 402 | 468 | 870 | |||

| Truck/Bus involved | TruckBus | 1 = Yes | 19 | 16 | 35 | |

| 2 = No | 523 | 616 | 1139 | |||

| Work Zone Present | WorkZonePrsnt | 1 = Yes | 9 | 6 | 15 | |

| 2 = No | 533 | 626 | 1159 | |||

| High SpeedLimit | HighSpeedLimit | 1 = “≥40 MPH” | 184 | 190 | 374 | |

| 2 = “<40 MPH” | 358 | 442 | 800 | |||

| Signal control | Signal_control | 1 = Yes | 207 | 257 | 464 | |

| 2 = No | 335 | 375 | 710 | |||

| Stop control | Stop_control | 1 = Yes | 129 | 178 | 307 | |

| 2 = No | 413 | 454 | 867 | |||

| Yield control | Yield_control | 1 = Yes | 9 | 5 | 14 | |

| 2 = No | 533 | 627 | 1160 | |||

| Uncontrolled | Uncontrolled | 1 = Yes | 197 | 192 | 389 | |

| 2 = No | 345 | 440 | 785 | |||

| Driver Characteristics | Driver Sex | driverSex | 1 = Male | 347 | 383 | 730 |

| 2 = Female | 195 | 249 | 444 | |||

| Driver age | Driverage_Lessthan25 | 1 = Yes | 85 | 92 | 177 | |

| 2 = No | 457 | 540 | 997 | |||

| Driverage_between25_60 | 1 = Yes | 253 | 279 | 532 | ||

| 2 = No | 289 | 353 | 642 | |||

| Driverage_geaterthan60 | 1 = Yes | 204 | 261 | 465 | ||

| 2 = No | 338 | 371 | 709 | |||

| Driver Distracted By | driverDistractedBy | 1 = Yes | 191 | 234 | 425 | |

| 2 = No | 351 | 398 | 749 | |||

| Driver Violator | driverViolator | 1 = Yes | 242 | 345 | 587 | |

| 2 = No | 300 | 287 | 587 | |||

| Driver Hazardous Action | driverHazdAction_carelessDriving | 1 = Yes | 39 | 45 | 84 | |

| 2 = No | 503 | 587 | 1090 | |||

| driverHazdAction_Disobeyded_TCD | 1 = Yes | 42 | 67 | 109 | ||

| 2 = No | 500 | 565 | 1065 | |||

| driverHazdAction_Failed_to_yield | 1 = Yes | 166 | 239 | 405 | ||

| 2 = No | 376 | 393 | 769 | |||

| Driver Intent | driverIntent_GoingStraight | 1 = Yes | 246 | 278 | 524 | |

| 2 = No | 296 | 354 | 650 | |||

| driverIntent_TurningLeft | 1 = Yes | 66 | 81 | 147 | ||

| 2 = No | 476 | 551 | 1027 | |||

| driverIntent_TurningRight | 1 = Yes | 113 | 162 | 275 | ||

| 2 = No | 429 | 470 | 899 | |||

| driverIntent_Stopped_on_road | 1 = Yes | 66 | 66 | 132 | ||

| 2 = No | 476 | 566 | 1042 | |||

| driverIntent_Backing | 1 = Yes | 10 | 15 | 25 | ||

| 2 = No | 532 | 617 | 1149 | |||

| driverIntent_Changing_Lanes | 1 = Yes | 41 | 30 | 71 | ||

| 2 = No | 501 | 602 | 1103 | |||

| Micro-mobility Device | Bicycle | Bicycle | 1 = Yes | 497 | 593 | 1090 |

| 2 = No | 45 | 39 | 84 | |||

| e_scooter | e_scooter | 1 = Yes | 25 | 20 | 45 | |

| 2 = No | 517 | 612 | 1129 | |||

| Wheelchair | Wheelchair | 1 = Yes | 14 | 13 | 27 | |

| 2 = No | 528 | 619 | 1147 | |||

| Skateboard | Skateboard | 1 = Yes | 6 | 6 | 12 | |

| 2 = No | 536 | 626 | 1162 | |||

| Micro-mobility Rider (MR) Characteristics | MR Sex | MSex | 1 = Male | 429 | 513 | 942 |

| 2 = Female | 113 | 119 | 232 | |||

| MR age | Mage_Lessthan25 | 1 = Yes | 219 | 226 | 445 | |

| 2 = No | 323 | 406 | 729 | |||

| Mage_between25_60 | 1 = Yes | 219 | 281 | 500 | ||

| 2 = No | 323 | 351 | 674 | |||

| Mage_geaterthan60 | 1 = Yes | 104 | 125 | 229 | ||

| 2 = No | 438 | 507 | 945 | |||

| MR Distracted By | MDistractedBy | 1 = Yes | 149 | 166 | 315 | |

| 2 = No | 393 | 466 | 859 | |||

| MR Violator | MViolator | 1 = Yes | 220 | 194 | 414 | |

| 2 = No | 322 | 438 | 760 | |||

| MR Hazardous Action | MHazdAction_Improper_lane_use | 1 = Yes | 91 | 93 | 184 | |

| 2 = No | 451 | 539 | 990 | |||

| MHazdAction_Disobeyded_TCD | 1 = Yes | 92 | 84 | 176 | ||

| 2 = No | 450 | 548 | 998 | |||

| MHazdAction_Failed_to_yield | 1 = Yes | 74 | 69 | 143 | ||

| 2 = No | 468 | 563 | 1031 | |||

| Micro-mobility Crash (MC) Location | MC Location | M_on_the_road | 1 = Yes | 491 | 557 | 1048 |

| 2 = No | 51 | 75 | 126 | |||

| M_on_the_shoulder | 1 = Yes | 20 | 20 | 40 | ||

| 2 = No | 522 | 612 | 1134 | |||

| M_in_bicycle_lane | 1 = Yes | 9 | 18 | 27 | ||

| 2 = No | 533 | 614 | 1147 |

| #Epoch | Learning Rate | Fold | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F-Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training Outputs | 10 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.8260 | 0.8516 | 0.7723 | 0.8100 |

| 2 | 0.7517 | 0.8033 | 0.6981 | 0.7470 | |||

| 3 | 0.7724 | 0.8236 | 0.7252 | 0.7713 | |||

| 4 | 0.8258 | 0.8583 | 0.7925 | 0.8241 | |||

| 5 | 0.8323 | 0.8609 | 0.8087 | 0.8340 | |||

| Mean | 0.80 | 0.84 | 0.76 | 0.80 | |||

| Validation Outputs | 10 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.8065 | 1.0000 | 0.7500 | 0.8571 |

| 2 | 0.8710 | 0.9444 | 0.8500 | 0.8947 | |||

| 3 | 0.8065 | 0.7770 | 0.8750 | 0.8231 | |||

| 4 | 0.8065 | 0.9444 | 0.7727 | 0.8500 | |||

| 5 | 0.8065 | 1.0000 | 0.7500 | 0.8571 | |||

| Mean | 0.82 | 0.93 | 0.80 | 0.86 | |||

| No. | Decision Rule | Prediction | %Frequency | Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | If [Bicycle = 1 & M_in_bicycle_lane = 1 & driverHazdAction_Disobeyded_TCD = 2 & MViolator = 2] | Minor/No Injury | 9.1 | 0.000 |

| 2 | If [Bicycle = 1 & M_in_bicycle_lane = 2 & driverHazdAction_carelessDriving = 1 & MViolator = 2] | Fatal/Serious Injury | 12.5 | 0.000 |

| 3 | If [Nighttime = 1 & M_on_the_shoulder = 1 & HighSpeedLimit = 1 & Mage_between25_60 = 1] | Fatal/Serious Injury | 6.2 | 0.000 |

| 4 | If [M_on_the_road = 1 & HighSpeedLimit = 2 & driverDistractedBy = 2 & Mage_between25_60 = 1] | Minor/No Injury | 3.1 | 0.000 |

| 5 | If [Intersection = 1 & M_on_the_road = 1 & Driverage_geaterthan60 = 1 & Mage_between25_60 = 2] | Fatal/Serious Injury | 4.7 | 0.000 |

| 6 | If [M_in_bicycle_lane = 2 & Uncontrolled = 1 & Mage_between25_60 = 1 & MDistractedBy = 1 & MHazdAction_Failed_to_yield = 1] | Fatal/Serious Injury | 1.6 | 0.000 |

| 7 | If [driverViolator = 1 & MSex = 2 & MDistractedBy = 2 & MHazdAction_Failed_to_yield = 1 & TruckBus = 1] | Fatal/Serious Injury | 7.8 | 0.125 |

| 8 | If [HighSpeedLimit = 2 & driverHazdAction_Disobeyded_TCD = 1 & driverIntent_Changing_Lanes = 1 & e_scooter = 1 & WorkZonePrsnt = 1] | Fatal/Serious Injury | 0.700 | 0.125 |

| 9 | If [Uncontrolled = 1 & driverSex = 1 & driverHazdAction_Disobeyded_TCD = 1 & MHazdAction_Failed_to_yield = 1] | Fatal/Serious Injury | 6.2 | 0.250 |

| 10 | If [M_on_the_road = 1 & driverSex = 2 & driverDistractedBy = 2 & driverViolator = 1] | Minor/No Injury | 10.9 | 0.273 |

| 11 | If [M_on_the_road = 1 & Driverage_geaterthan60 = 2 & Mage_geaterthan60 = 1 & Bicycle = 1 & TruckBus = 1] | Fatal/Serious Injury | 9.4 | 0.308 |

| 12 | If [driverViolator = 1 & Mage_geaterthan60 = 1 & MHazdAction_Failed_to_yield = 1] | Fatal/Serious Injury | 14.1 | 0.312 |

| 13 | If M_on_the_road = 1 & Driverage_Lessthan25 = 1 & driverHazdAction_Disobeyded_TCD = 1 & e_scooter = 1] | Fatal/Serious Injury | 23.4 | 0.333 |

| 14 | If [Intersection = 1 & WetPav = 1 & Nighttime = 1 & Signal_control = 1 & driverIntent_TurningLeft = 1 & Mage_Lessthan25 = 1 | Fatal/Serious Injury | 1.6 | 0.333 |

| 15 | If [M_on_the_road = 1 & driverViolator = 2 & e_scooter = 1] | Minor/No Injury | 12.5 | 0.385 |

| 16 | If [M_on_the_road = 1 & Driverage_Lessthan25 = 1 & driverSex = 1 & driverDistractedBy = 1 & e_scooter = 1] | Fatal/Serious Injury | 3.1 | 0.400 |

| 17 | If [M_on_the_road = 1 & Driverage_Lessthan25 = 1 & driverSex = 1 & driverDistractedBy = 2 & e_scooter = 1] | Minor/No Injury | 6.2 | 0.417 |

| 18 | If [driverDistractedBy = 1 & driverIntent_TurningRight = 1 & MViolator = 2 & Wheelchair = 1] | Fatal/Serious Injury | 17.2 | 0.429 |

| 19 | If [driverDistractedBy = 2 & driverIntent_TurningRight = 1 & MViolator = 2 & Wheelchair = 1] | Minor/No Injury | 1.6 | 0.435 |

| 20 | If [Intersection = 1 & driverIntent_TurningLeft = 1 & MViolator = 1 & MHazdAction_Improper_lane_use = 1] | Fatal/Serious Injury | 3.1 | 0.444 |

| 21 | If [HighSpeedLimit = 2 & driverDistractedBy = 2 & Mage_Lessthan25 = 1 & TruckBus = 2] | Minor/No Injury | 20.3 | 0.446 |

| 22 | If [HighSpeedLimit = 2 & Stop_control = 1 & Driverage_between25_60 = 1 & driverIntent_TurningLeft = 1 & MViolator = 1 & Skateboard = 1] | Fatal/Serious Injury | 4.7 | 0.462 |

| 23 | If [Yield_control = 1 & driverIntent_Changing_Lanes = 1 & Mage_geaterthan60 = 1] | Fatal/Serious Injury | 3.1 | 0.500 |

| 24 | If [Nighttime = 1 & MHazdAction_Failed_to_yield = 1 & Bicycle = 1] | Fatal/Serious Injury | 7.8 | 0.500 |

| 25 | If [M_on_the_shoulder = 1 & HighSpeedLimit = 1 & Bicycle = 1] | Fatal/Serious Injury | 14.1 | 0.523 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qawasmeh, B.; Oh, J.-S.; Kwigizile, V. Micro-Mobility Safety Assessment: Analyzing Factors Influencing the Micro-Mobility Injuries in Michigan by Mining Crash Reports. Future Transp. 2024, 4, 1580-1601. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp4040076

Qawasmeh B, Oh J-S, Kwigizile V. Micro-Mobility Safety Assessment: Analyzing Factors Influencing the Micro-Mobility Injuries in Michigan by Mining Crash Reports. Future Transportation. 2024; 4(4):1580-1601. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp4040076

Chicago/Turabian StyleQawasmeh, Baraah, Jun-Seok Oh, and Valerian Kwigizile. 2024. "Micro-Mobility Safety Assessment: Analyzing Factors Influencing the Micro-Mobility Injuries in Michigan by Mining Crash Reports" Future Transportation 4, no. 4: 1580-1601. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp4040076

APA StyleQawasmeh, B., Oh, J.-S., & Kwigizile, V. (2024). Micro-Mobility Safety Assessment: Analyzing Factors Influencing the Micro-Mobility Injuries in Michigan by Mining Crash Reports. Future Transportation, 4(4), 1580-1601. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp4040076