1. Introduction

Disabled children are heterogenous and “have long-term physical, mental, intellectual, or sensory impairments which…may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others” [

1] (p. 2). An estimated 16% of the world’s population, approximately 240 million children worldwide, are living with a disability [

2], including about 95,000 children in New Zealand (N.Z.) [

3]. Parents of disabled children are 15 times more likely to report feeling unable to cope with their child’s needs and overwhelmed, compared to parents of non-disabled children [

4].

Family-Centred Care is widely considered the best practice in healthcare service delivery to children and families. Its core principles, such as respect for children and families, shared decision-making, and collaboration, are well established [

5,

6]. When implemented effectively, Family-Centred Care is linked to improved child health and development outcomes, as well as enhanced family engagement [

6]. A literature review by King and Chiarello [

7], exploring the practical considerations of Family-Centred Care for Cerebral Palsy children and their families, reinforces these core beliefs and highlights the importance of respect, appreciation of the family’s influence on the child’s well-being, and collaboration. However, despite general agreement on core Family-Centred Care principles, literature consistently reports challenges with implementation. Shields [

8] notes a variety of descriptions of Family-Centred Care but emphasises that very few offer specific definitions. Similarly, a scoping review of Family-Centred Care by Kokorelias et al. [

9] highlights a lack of concrete implementation strategies. These findings are echoed by Kuo et al. [

10], who note fundamental misunderstandings in how to enact Family-Centred Care in practice. Carrington et al. [

11] also report inconsistencies in how Family-Centred Care principles are applied, largely due to the heterogeneous nature of disabled children.

Despite the known benefits of Family-Centred Care, there remains a limited understanding of how these implementation challenges are experienced by the key stakeholders involved, namely families and service providers. Uniacke et al. [

12] have purported the need to better understand what families require from Family-Centred Care. As noted by Shields [

8], understanding the parents’ perspective is of utmost importance to improve processes and outcomes of services for disabled children and their families.

Health providers, such as physiotherapists, may provide valuable paediatric rehabilitation and support for disabled children and their families [

13]. However, beyond the challenges of implementing Family-Centred Care, access to and the quality of paediatric healthcare services remain key concerns [

14]. An international survey exploring the strengths and weaknesses of paediatric physiotherapy services across 47 countries by Camden et al. [

15] highlights limited resources, including lack of funding and staffing, as key factors impairing physiotherapy services. Such challenges are evident within New Zealand physiotherapy services, which experience system-level constraints due to issues such as dual funding systems, creating disparities in service access and eligibility constraints [

16]. Such resource constraints are global issues, with healthcare systems commonly facing financial pressures, underdeveloped infrastructure, and workforce shortages [

17,

18]. To improve access to quality healthcare, it is essential to understand stakeholders’ experiences to guide future initiatives. The Medical Research Council highlights the importance of co-design with stakeholders when developing a novel complex intervention [

19], and Physiotherapy New Zealand’s Person and Whānau Centred Care model similarly emphasises the importance of stakeholder involvement in service design [

20].

The purpose of this multi-method study was to explore and integrate the experiences and perceptions of healthcare service providers and service users on Family-Centred Care. Information was gathered to inform strategies to help healthcare service providers enhance the service engagement and delivery for disabled children and their families.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This research was underpinned by constructionist epistemology and relativist ontology, shaping an interpretive paradigm that recognises that knowledge is constructed through lived experience and that both participant and researcher perspectives are shaped by their unique contextual circumstances [

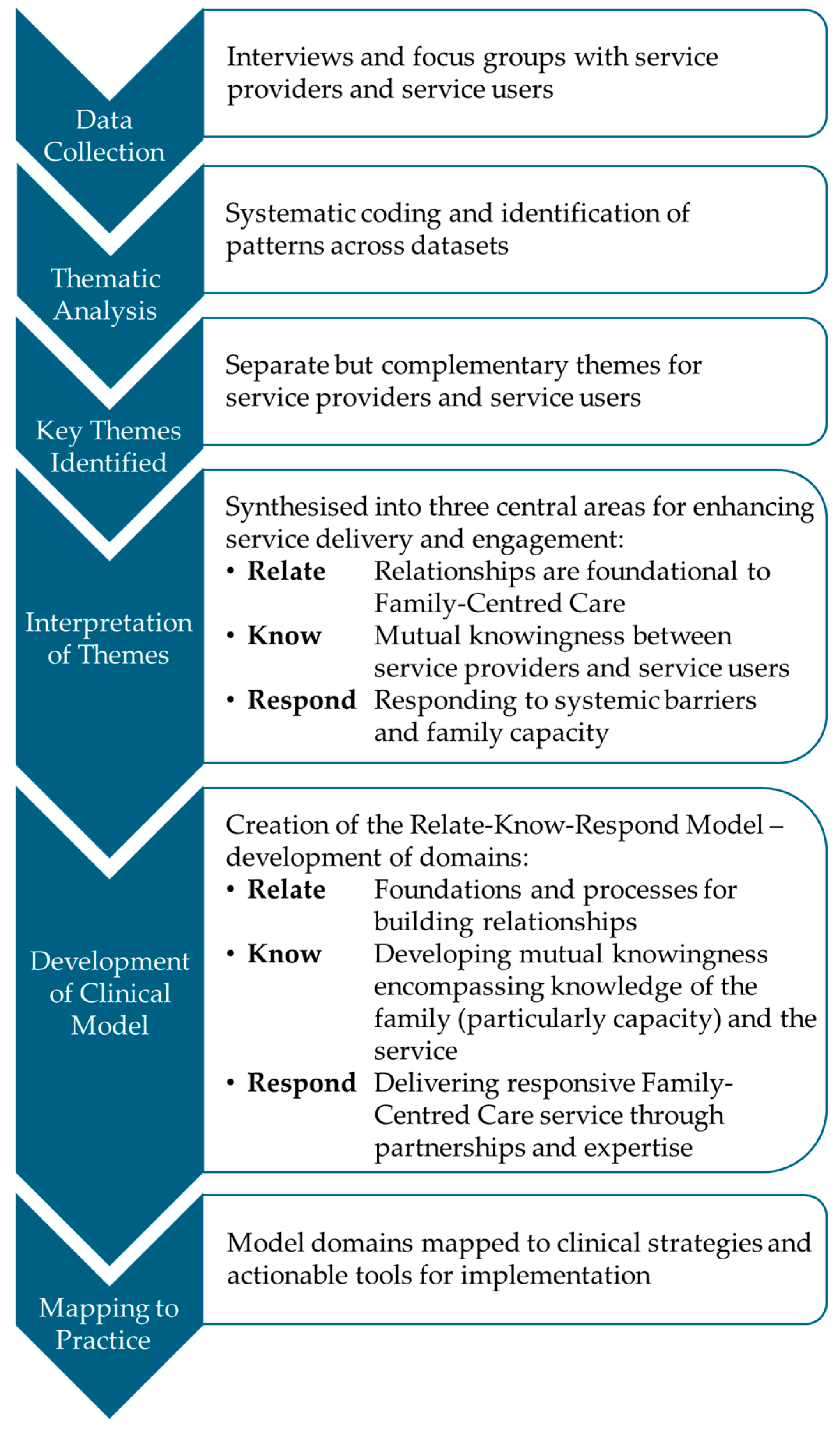

21]. The multi-disciplinary research team consisted of four academic researchers with expertise in paediatric physiotherapy, qualitative methods, social geography, and health service delivery. Reflexivity was pursued throughout the study design and analysis stages. The primary researcher also completed reflective statements prior to commencing the study and field notes after each interview. Qualitative methodologies including focus groups and one-on-one interviews are valuable ways to explore stakeholders’ perceptions, feelings and beliefs about their experiences [

22]. Semi-structured qualitative interviews and focus groups were conducted with paediatric healthcare service providers and service users. Theoretical frameworks of the International Classification of Disability and Functioning [

23] and the Social Ecological model of health [

24] guided the deductive and iterative six-phase thematic analysis as outlined by Braun and Clarke [

25]. Ethical approval was granted by the Human Ethics Committee, University of Otago (H23/014, 3 March 2023).

2.2. Recruitment

Both healthcare service providers and service users were invited to participate in the research. For the purposes of this study, service providers were defined as, and limited to, therapy service providers and support service advisors for disabled children. Whilst we acknowledge that interdisciplinary paediatric healthcare teams frequently include a wide range of allied health professionals, the inclusion of all professionals was beyond the scope of this project. Therefore, therapy service provider inclusion was limited to Physiotherapy, Occupational Therapy, Speech Language Therapy, allied health professionals, and Music Therapists. The inclusion of non-clinical support service advisors recognises these individuals as key stakeholders and reflects an understanding of health as a holistic concept, encompassing social and emotional well-being, not limited to healthcare alone.

When recruiting therapy service providers, the primary researcher directly emailed study information sheets and invitations to participate to the research teams’ well-established network of paediatric healthcare and special education service providers across New Zealand, including the professional body of Physiotherapy New Zealand Paediatric Special Interest Group and ministry-funded Te Whatu Ora Child Development Services.

When recruiting support service providers, the primary researcher directly emailed publicly available paediatric support services, including the Cerebral Palsy Society New Zealand, Parent to Parent Network, and other services identified through internet searches.

Service users included disabled children and their families. When recruiting service users, the primary researcher sent study information to the same known network of healthcare service providers and asked them to distribute the information to their family contacts. Public advertising platforms, including social media (Facebook) and public websites (Cerebral Palsy Society of NZ), were also used to increase reach.

All interested individuals contacted the primary researcher directly via email or phone, at which time further information about the study was provided and eligibility to participate was determined (

Table 1). Those who accepted the invitation to participate completed a secure online consent form and scheduled a time for either an in-person or Zoom interview with the primary researcher as determined by the participant’s preferences.

2.3. Semi-Structured Interviews and Focus Groups

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with advisor service providers and family participants to allow for in-depth exploration of individual perspectives and experiences. These one-on-one interviews acknowledged the unique context of each participant and encouraged context-specific reflection. In contrast, focus groups were conducted with therapy service providers to facilitate discussion of shared practices and explore how their varying roles within the healthcare environment were constructed.

All interviews and focus groups involved an open-questioning technique in which the precise nature of the questions was not determined in advance but depended on the way in which each interview/focus group developed, allowing for questions to generate iteratively. Semi-structured interview/focus group guides were developed for each stakeholder group by the primary researcher (L.C.). These guides were steered by the research aims and refined following consultation with the research team. The general lines of questioning included experiences of healthcare and concepts of Family-Centred Care (

Table A1).

All interviews and focus groups were Zoom video and/or audio recorded [

26] with the participant’s permission. Participant demographics were recorded on a pre-determined table and stored in Microsoft Excel [

27] on a password-protected computer only accessible to the primary researcher. At the completion of the interview/focus group, a grocery voucher was given to each family participant in recognition of their time.

Recorded interviews and focus groups were transcribed verbatim either by a professional transcription service or by the Otter AI transcription tool [

28]. Transcripts were then checked for accuracy and anonymised by the primary researcher. Participants were coded as therapists (T1–T16), advisors (A1–A9), and family members (F1–F25) to maintain confidentiality. The primary researcher used NVivo qualitative data analysis software to complete reflexive thematic analysis on each transcript, guided by Braun and Clarke’s [

25] six-phase process. This involved familiarisation with the data, systematic coding, identifying and reviewing themes, defining them clearly, and producing the thematic report. Early phases of the analysis were verified by MP, and all researchers reviewed the final themes.

3. Results

3.1. Description of Interviews and Focus Groups

3.1.1. Advisor Service Provider-Interviews

In-person interviews were conducted with nine advisor service providers from Dunedin (South Island, n = 4) and Auckland (North Island, n = 5) in New Zealand. Interview duration ranged from 58 to 88 min. Advisors represented a range of non-clinical but highly relevant sectors, supporting disabled children and their families. Their roles spanned adapted physical activity, inclusive performance, disability advocacy, community service coordination, and education. Employers included the Ministry of Education (n = 1), charitable trust support services (n = 7), and a private business support service (n = 1). Areas of focus included parent and adolescent support groups, condition-specific and general disability services, and coordination of sporting and artistic activities. Experience of each advisor in paediatric support roles ranged from between 1 and 33 years. While all advisors were interviewed within two locations, six advisors’ roles spanned regional and nationwide areas.

3.1.2. Therapist Service Provider-Focus Groups

Three in-person focus groups were conducted with a total of 16 therapists spread across New Zealand (Dunedin n = 3, Hamilton n = 6, Auckland n = 7). Focus group duration ranged from 85 to 130 min. Participants were physiotherapists (n = 10), occupational therapists (n = 4), a music therapist (n = 1), and a speech and language therapist (n = 1). Therapists worked for Te Whatu Ora (n = 6), within paediatric private practice (n = 6), at a specialist school (n = 5), for the Ministry of Education (n = 1), or a combination of these. Therapist professions represented in each focus group reflected the recruitment location, with specialist schools including a diverse mix of therapists. Therapists had been working in paediatric settings from between 6 and 30+ years and were all working in multidisciplinary teams.

3.1.3. Service User-Family Interviews

A total of 25 service users/family participants were recruited from nine different locations across New Zealand (North Island n = 15, South Island n = 10). Interview duration ranged from 57 to 135 min. A total of 13 interviews were conducted one-on-one, while six were conducted with two participants, three involving a parent and youth and three involving two parents. Interviews were either in-person at the participant’s choice of location (n = 10) or via Zoom audio-visual conferencing (n = 9). Participants included youths (n = 3), mothers (n = 18), stepmothers (n = 2), and fathers (n = 2). Ethnicities included New Zealand European/Pākeka (n = 10), Māori (n = 5), English (n = 2), Nigerian (n = 1), and Afghan (n = 2). Over half of the adult participants were not currently employed (n = 13), with nine identifying as full-time unpaid caregivers. Current and previous occupations included roles in education (n = 4), healthcare (n = 2), farming (n = 1), and community services (n = 1), public servants (n = 2), human resource managers (n = 2), and housing developers (n = 2). Adult participants were either married (n = 14), remarried (n = 2), or divorced (n = 6). All but two participants had one disabled child, and two participants had two disabled children. Participants had in total one (n = 5), two (n = 10), three (n = 4), or four children (n = 3). Two families had experienced bereavement of the child they discussed in the interview.

3.2. Thematic Analysis of Service Provider and Service User Data

‘Relationships enhance knowingness’ was identified as the overarching theme across both service provider and service user data. Participants described relationships as critical to meaningful service delivery and engagement, with mutual understanding, or knowingness, between service providers and service users being viewed as essential for success. This depth of understanding determined how well services and families fit together. Service providers and service users shared a subtheme focused on ‘individual characteristics’, though each group described these in unique ways (

Table 2). In addition, both groups of service providers identified a second subtheme related to their ‘perceptions of families’, while service users instead described a distinct subtheme focused on their ‘experiences of therapy’ (

Table 2).

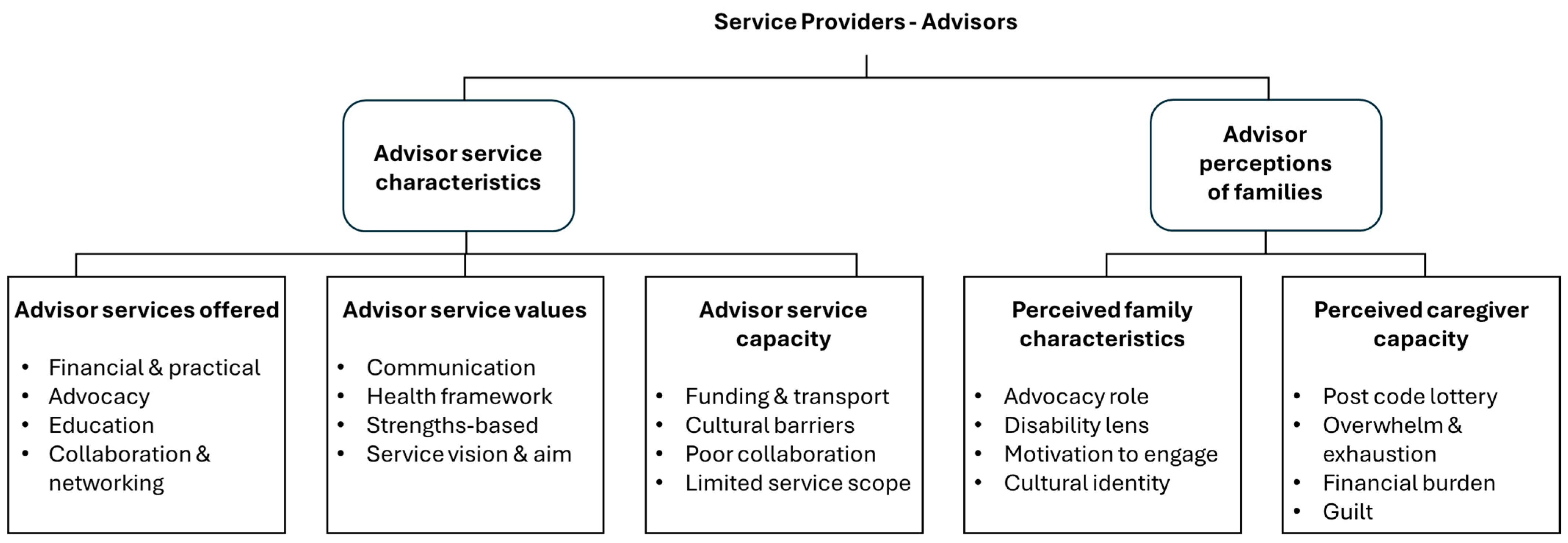

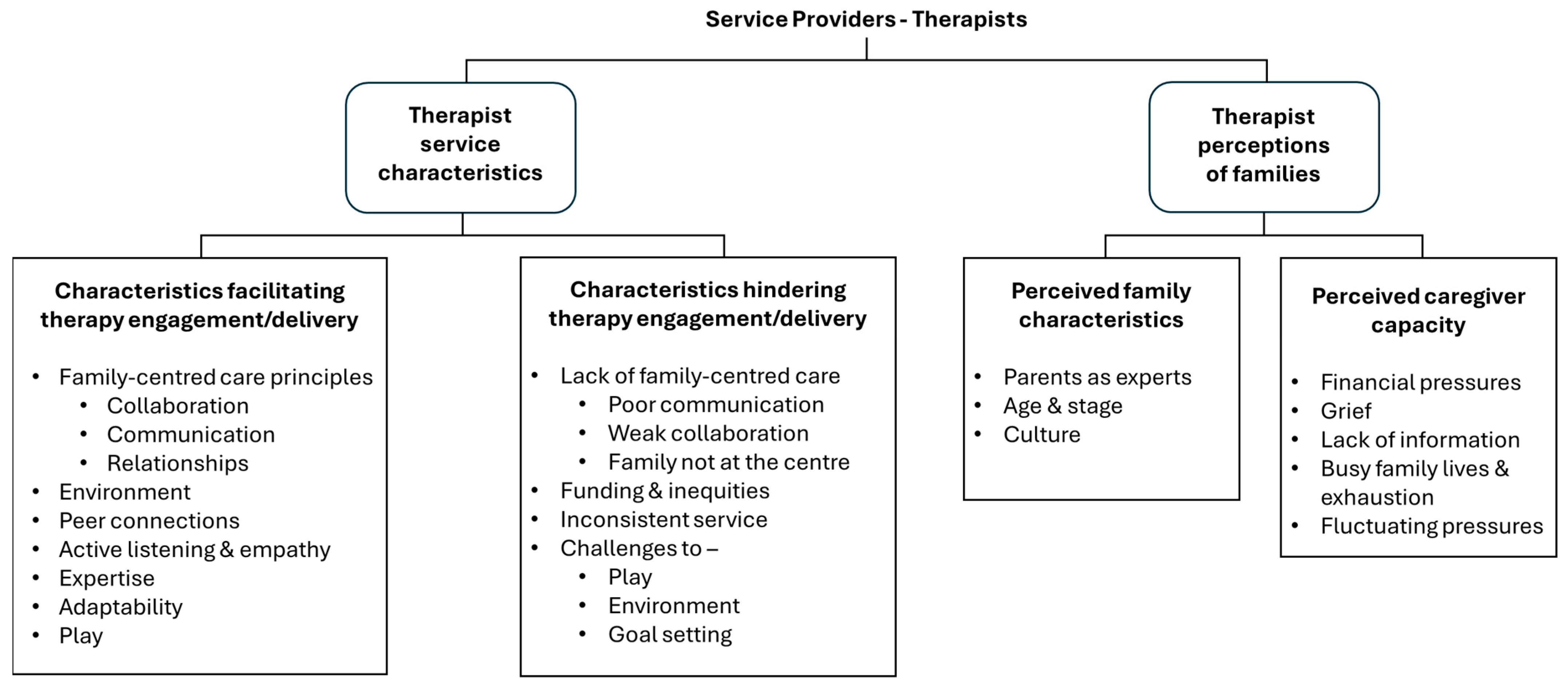

3.3. Service Provider Perspectives

Two key themes were derived from advisor and therapist service provider data: (1) service provider characteristics and (2) service provider perceptions of families. Service provider characteristics encompassed the unique systems, affiliations, and values, which shaped how advisor and therapist services interacted with disabled children and their families. Distinct differences between the characteristics of the two service provider groups reflected their unique roles (

Table 3). Service provider engagement with service users was influenced by how providers interpreted family characteristics, including their unique needs and circumstances.

3.3.1. Service Provider Characteristics

Advisors described three core service characteristics: (1) Service values, (2) Services offered, and (3) Service capacity (

Figure 1). Advisor characteristics reflected their key role in connecting families with resources and navigating complex systems and acknowledged the systemic constraints they worked within.

The advisor’s service values acted as guiding principles, which shaped the design of their services, focused on information, education, and advocacy. Examples of the advisor’s service values included open, honest and timely communication. They explained how these values helped foster strong relationships with families of disabled children and other support services. Inclusivity was another a core value, reflected in advisors’ promotion of participation in recreational activities, connections to families with lived experience of disability and links to peers in community settings. Service values were focused on holistic healthcare models and frameworks, such as the International Classification of Functioning and Disability (ICF) and Family-Centred Care, as advisors considered the needs and influences of not only the disabled child but also their family, environment and personal factors. For example, participation, a focus for many advisors, is a central component of the ICF and aligned directly with advisor service values focused on inclusion.

Advisor service capacity determined the practical limits, aims, scope, and reach of support, with systemic constraints, particularly funding challenges, being a significant factor. For example, one advisor explained that her service was only able to support young people with “primarily physical [impairments, because] there’s a limited amount of funding” (A4). Funding-related staffing and time constraints further reduced opportunities for meaningful collaboration with families and other services.

Therapists’ key characteristics reflected their role in the delivery of therapeutic services and were perceived to either facilitate or hinder service engagement and delivery (

Figure 2). Therapy provision was enhanced when therapists applied Family-Centred Care principles, particularly strong communication, collaboration, and relationship-building. These practices were supported by therapists’ personal attributes, including adaptability, expertise, and empathy. Open, non-judgemental, and strengths-based communication was essential for understanding families’ needs and forming connections. Therapists noted that these strategies meant that when “barriers and challenges [were encountered]…you’ve got that relationship, and they trust you” (T11). The use of play was a characteristic unique to therapists, with many highlighting that therapeutic play supported child development and fostered relationships by building connection with the child. Therapists acknowledged the importance of the environment and valued working in families’ homes, as this provided insight into daily life and helped them design engaging interventions based on children’s preferences, available equipment, and specific challenges. In addition, therapists recommended using a variety of communication tools, including written as well as videoed instructions, to provide visual guidance and encourage feedback from families.

As with advisors, therapists associated certain service characteristics, particularly those shaped by systemic barriers, with challenges in service engagement and delivery. Therapists expressed frustrations and concerns over disparities caused by funding, which influenced service provision, and the strict funding criteria that many disabled children struggled to meet. When reflecting on the dual funding systems in New Zealand (public health system vs. Accident Compensation Corporation levy-based insurance scheme), one therapist noted, “I think it’s difficult that there are different services for different children and different families” (T3). In addition, siloed and fragmented services contributed to poor communication and weak collaborative relationships. One therapist reflected, “If I’m really busy, I often don’t do it well, I don’t engage enough” (T9), highlighting how constrained time and resources can directly undermine relationship building. Therapists described how these issues affected their capacity and influenced their ability to deliver Family-Centred Care as intended.

3.3.2. Service Provider Perceptions of Families

Both groups of service providers described their perceptions of families to include family characteristics and the caregiver’s capacity. Family characteristics provided context about the family, such as demographics, culture, and values. While caregiver capacity determined how effectively families could navigate and access services. Service providers’ perceptions of key family characteristics were shaped by the nature of their service. Therapists focused on family characteristics that influenced their therapeutic approach, such as the age and stage of the child and the parent’s role as experts on their child and family culture. In contrast, advisors focused on family characteristics that influenced the support they offered, such as families’ beliefs about disability and motivation to engage with the service, reflecting their roles as disability advocates.

Service providers identified key factors they perceived to influence family capacity, including fluctuating pressures, busy lives, knowledge gaps, financial strain, and geographical location. These overlapping and interconnected factors were significantly impacted by systemic barriers to healthcare and collectively influenced families’ ability to engage with service providers. Therapist perspectives also focused on the impact of individual-level issues on the families’ capacity, such as the young person’s declining health. In contrast, advisors were more likely to describe system-level issues, such as financial constraints restricting families’ access to their services and variation in available resources and services across geographical regions. An advisor for a nationwide support service noted that “the ability to serve different communities is very restricted, often by where they live” (A7).

3.4. Service User Perspectives

Two themes were derived from the service user data: family characteristics and therapy experiences (

Figure 3). Family participants described their collective family characteristics and values that shaped who they were and how they identified, as well as their perceptions and experiences of the services involved with their child.

3.4.1. Service User Characteristics

Key service user characteristics were identified as family capacity, advocacy roles adopted by parents, and expressions of parental pride. These characteristics shaped families’ perceptions and experiences of healthcare while also influencing their sense of identity and unique perspectives.

Families described their capacity as being influenced by a range of dynamic factors, both singular stress events and ongoing, chronic sources of stress, whose impact and significance fluctuated over time. Factors included daily pressures, life events, emotional strain, and systemic challenges. Many families faced stress due to the time and effort associated with managing appointments, therapies, and daily caregiving with minimal support, noting that “managing the admin [istration] of all this is like a part-time job in itself” (F9). The demands on parents’ time reduced their capacity to engage in therapy and participate in other areas of life. For example, many parents had left full-time employment to become either part- or full-time caregivers and advocates for their child.

Advocacy roles assumed by families were another key family characteristic. Families were under constant pressure to advocate for their child’s health, inclusion, and well-being, which also contributed to their exhaustion and feelings of guilt. Caregivers’ ability to advocate was diminished during times of reduced capacity, influenced by fluctuating factors such as sleep deprivation, age and stage of the child, and sickness. In addition, some families reported that due to their advocacy efforts they were perceived by healthcare providers as ‘difficult parents’. Battling against such a paternalistic, medical model approach further depleted their capacity and led to advocacy fatigue. Families with relevant professional experience, in areas of education or health, often felt better equipped to navigate systems, but still experienced overwhelm.

Trauma and grief, particularly related to birth events, health mismanagement, deterioration, or child loss, left some families in ongoing states of distress, increased their mental load, and diminished their ability to manage additional demands. Feelings of isolation from their communities and a lack of understanding or support from services compounded this strain. One parent noted that “Families like ours…they’re tired from navigating an inaccessible system in an inaccessible society… [they] just want to be supported [by] someone who will scoop them up and love them and not expect too much” (F1). As one family member noted, when therapists did not fully understand their limited capacity, “the disparity between expectations and reality is going to be quite large” (F6).

Despite their challenges, the profound pride parents felt for their children was another defining family characteristic. Parents described the admiration they felt for their child’s strengths and daily accomplishments. They emphasised the joy their children brought to their family and to others through unique characteristics, including tolerance, patience, humour, happiness, resilience, problem-solving, kindness, and consistency. One parent described her daughter as “very patient, she tolerates a lot. She’s very forgiving and just accepting. It’s wonderful, [there’s] a lot to learn from [her]” (F1). Parent’s affirmations often followed recollections of distressing healthcare experiences, reflecting a strong desire for their child’s strengths and accomplishments to be recognised and valued.

3.4.2. Service Users’ Therapy Experiences

Service users described how their satisfaction in therapy was shaped by a dynamic interplay of factors, including communication, service access, therapist continuity, and the quality of relationships with providers. Satisfaction was greater when service delivery reflected Family-Centred Care principles.

Family-professional relationships based on partnership and mutual respect contributed to family alliance with therapy services and enabled open communication without fear of judgement. One parent noted, “You have to really know the family, to spend time with them and build that very…respectful, trusting, safe relationship, so that the family feel like they can be honest and won’t be judged” (F6). When long-term relationships were maintained, this consistent contact supported deeper understanding of influencing features, including culture and capacity. Families appreciated not having to continually retell their story and valued service providers who recognised their limited capacity to seek additional information. In addition, one parent explained that when services acknowledged their cultural and religious values, it was “very helpful and helped us to feel connected to the services” (F14).

Mutually respectful collaborative communication, where feedback was encouraged and adjustments made accordingly, also increased family trust in service providers. As one parent reflected, “I felt heard and believed and that’s why I trusted” (F17). Strong interprofessional communication also enhanced therapy satisfaction when families did not have to serve as intermediaries between different services. This was particularly important when children were supported by several professionals within and across systems (e.g., health and education), and problems arose when services did not share information effectively.

Families’ therapy satisfaction was also shaped by systemic factors. Families frequently reported delays in accessing appointments, equipment, or services. Parents noted, “Everything’s a waitlist in the disabled world” (F10), and “You still can’t get a [wheel] chair in a timely manner” (F2). Service limitations disrupted service continuity, resulting in tensions and a sense of abandonment, leaving families feeling “disheartened and disappointed” (F11). Disruptions were particularly evident during transition periods, such as entering or moving schools or shifting to adult health services, which families described as “no man’s land” (F16).

Funding was another persistent barrier affecting flexibility in choice of services, the type of therapy available, and even where families lived. One family relocated to a larger city to get better support and explained, “That’s why we moved to Hamilton…[we] needed more of a wraparound service” (F16). Geographic inequities, discrepancies between funders, and funding restrictions created more work and stress for the family. These issues compounded emotional and logistical burdens and negatively impacted families’ capacity and therapy satisfaction.

4. Discussion

Exploring the perspectives of healthcare service providers and service users offered valuable insight into the factors shaping their interactions, perceptions, and experiences of service delivery and utilisation within Family-Centred Care. Three critical areas were identified as central to enhancing service delivery and promoting meaningful engagement with disabled children and their families: (1) Relate—the foundational role of relationships in Family-Centred Care; (2) Know—the concept of ‘mutual knowingness’ between service providers and service users; and (3) Respond—the importance of responding to systemic barriers and family capacity. While the fundamental role of relationships in Family-Centred Care is widely recognised, the latter two areas contribute novel insight into how service providers can address both personal and systemic factors that shape family experiences of healthcare.

4.1. Relate—Relationships Are Foundational to Family-Centred Care

4.1.1. The Need for Relationships in Family-Centred Care

Moving from a purely theoretical approach to Family-Centred Care requires consistent and practical implementation in clinical practice. However, as observed in our study and others, Family-Centred Care is variably interpreted, and its principles are often inconsistently applied [

11]. The synthesis of service provider and service user perspectives reinforces the value of strong, trusting relationships as a foundation for effective Family-Centred Care, widely acknowledged as the gold standard for paediatric healthcare delivery [

6].

Our research found that strong, trusting relationships helped families to feel safe to express themselves, enabling a deep understanding of family context, preferences, capacity, and values. Honest, respectful communication and collaborative care were central to building this trust. When providers took time to actively listen and engage meaningfully, families felt heard, respected, and empowered to share their unique insights, without fear of judgement. This relational connection laid the foundation for mutual understanding between families and services.

These findings are consistent with those of partnership and shared decision-making, which are established principles of Family-Centred Care [

29,

30]. Allen et al.’s systematic review of 24 papers similarly found that strong relationships between child health practitioners and families formed the foundation of patient- and Family-Centred Care for young adults living with chronic disease and their families [

31]. Our findings reinforce that such partnerships are essential and that their impact depends on a foundation of trust, which is built through consistent respectful communication.

4.1.2. Communication and Collaboration as Pillars for Relationships

Family-Centred Care principles of communication and collaboration were identified as pivotal and interconnected concepts essential for promoting meaningful engagement in family-professional relationships. These findings are supported by existing literature highlighting effective communication as a key influencing factor for healthcare collaboration [

32] and Family-Centred Care [

9]. Similarly, a qualitative study in an educational setting by Avari et al. [

33] highlighted the importance of in-person communication with families as an essential component to building strong family-professional partnerships

Open, honest, and transparent communication was valued by all stakeholders, as it enhanced trust, reduced misunderstandings, and facilitated collaboration with other support systems. Conversely, a lack of effective collaboration and communication contributed to service gaps and fragmentation across services and breakdowns in relationships. Ineffective coordination between services disrupted continuity of care, created long waitlists, and reduced opportunities for working together, further eroding relationships.

4.1.3. Building Mutual Knowingness

To address these issues, communication and collaboration must be prioritised in both policy and practice. The American Academy of Pediatrics [

34] similarly emphasises that clear communication and shared goals are key elements of an effective team. They note that alignment between services not only enhances consistency but also encourages collaborative problem solving [

34]. Service providers should foster communication by sharing honest and transparent information about their services, including their service limitations, to build trust with the families.

Importantly, the use of play in therapy emerged as a practical, relationship-building tool. Therapists described how play helped establish rapport with children while supporting therapeutic engagement in ways that were both enjoyable and meaningful for families. Without such relationships, Family-Centred Care risks becoming superficial and difficult to implement, particularly in the face of systemic barriers.

4.2. Know—Mutual Knowingness Between Service Providers and Service Users

Trusting relationships are the foundation to ‘mutual knowingness’, a concept introduced by our research as central to the implementation of Family-Centred Care. Distinct from rapport, mutual knowingness is a relational understanding of each other’s characteristics, context, and systemic constraints, and what helps or hinders this understanding. It is an iterative process shaped by both parties’ unique attributes and the systemic barriers influencing healthcare provision, requiring a nuanced understanding of both family and service capacity.

4.2.1. Relational Understanding for Mutual Knowingness

Building mutual knowingness in practice requires that both service providers and families are willing and able to share relevant information about their characteristics and constraints. This transparency supports alignment between service roles and family needs, helping to ensure families direct their limited energy toward appropriate services. When service roles are unclear or not clearly communicated, families tend to form unrealistic expectations, leading to misunderstandings and mistrust and reduced engagement.

4.2.2. Systemic Constraints, Fragmentation and Knowingness

Systemic barriers are a significant contextual characteristic that must be understood and communicated openly. As demonstrated in this research, such barriers influence both the service’s ability to deliver care and the families’ capacity to engage. When both parties have a shared understanding of the systemic constraints affecting each other, they may be better able to temper their expectations, explore alternative approaches, and develop a deeper appreciation for the challenges involved.

Systemic barriers are examples of social determinants of health, everyday conditions, including environment and socioeconomic status, which shape an individual’s health and well-being, and contribute to health inequities [

35]. The World Health Organisation emphasises that progress must be made in reducing the barriers for people to seek and receive the care they need [

36]. In the current research, both service providers and families consistently identified funding limitations, resource constraints, and fragmented service delivery as key barriers. These led to inconsistent care, limited provider capacity, and increased burden on families.

Inconsistent funding and complex funding processes frequently caused frustration and stress for all stakeholders. These findings align with Goodyear-Smith and Aston’s review of the New Zealand health system, which notes that while government-funded accident compensation offers significant benefits to those that receive it, inequities exist because funding entitlements depend on whether a health issue is acquired through accidental injury or other causes [

37].

Most families in our research were deeply reliant on financial assistance, consistent with Allshouse et al.’s review showing that families of children with medical complexity often bear the costs of accessible transportation, home modifications, and assistive technologies [

38]. Although Allshouse et al. present the experiences of parents in the United States, similar challenges were discussed by families in this study. UNICEF has also recognised that disabled people encounter a multitude of expenses [

39]. Consistent with this, families in our study strongly valued support from providers who helped navigate funding systems or collaborated with other services to secure resources.

Systemic funding limitations also constrained service provider capacity by affecting staffing levels and working hours. As a result, a smaller number of providers were responsible for meeting growing demand and managing large caseloads, which constrained their time and undermined their ability to form strong relationships and tailor support.

Service providers held divergent perspectives on what influenced their own service capacity. Therapists tended to focus on how their service capacity was shaped by systemic constraints, such as funding and time pressures, and reflected on how these factors affected their individual-level interactions with families. In contrast, advisors emphasised the broader capacity of their service as a key determinant of service success. Therapists’ roles continued despite systemic constraints, albeit under increased demand, whereas advisor services were often dependent on specific funding streams or policy support and could cease to exist entirely without either of these. Indeed, one of the advisor services involved in this research was discontinued following the data collection due to financial instability. This structural vulnerability may explain why advisors were more likely to attribute service effectiveness, or ineffectiveness, to external factors, highlighting how systemic constraints shape service engagement and delivery at both individual and organisational levels.

Fragmentation was another consistently reported challenge. Services often operated in isolation rather than in coordinated and collaborative ways, an issue also reported by Sharma et al. [

40], leading to inefficiencies, which negatively impact patient experience and outcomes [

41,

42]. Worldwide healthcare systems face critical challenges due to a range of factors, including workforce shortages and inadequate funding contributing to a lack of sustainability [

43].

Families also described geographic inequities in service availability and accessibility, often referred to as a ‘postcode lottery’ [

44], with variability between regions and across healthcare systems hindering consistent engagement. Some families in this research shared their difficult experiences of travelling long distances or needing to move to new locations to receive appropriate services. These disruptions negatively affected mutual knowingness, as they interrupted continuity of care and required families to repeatedly build new relationships from scratch.

Transitions between services also disrupted continuity, such as moving from childhood services to school-based therapy or from paediatric to adult services. These transitions required families to build new relationships and navigate unfamiliar systems. These findings align with extensive research on education and health transitions, where poor communication, limited collaboration, and inconsistent care are common barriers [

45,

46]. In a systematic review of 57 articles, Gray et al. identified these relational disruptions as barriers for children with chronic illness transitioning from paediatric to adult healthcare [

47]. Allshouse et al. [

38] note that the extent of challenges created due to fragmented services are often only truly understood by the families who experience them.

An additional insight from our findings was the perceived invisibility of support services. These services, while highly valued by families, were often perceived as ‘supplementary’. This may reflect broader societal values that prioritise medical interventions over participation-focused supports. This invisibility contributed to a lack of service knowingness, where families could not access or fully understand poorly communicated or undervalued services. In this study, families often prioritised access to therapy, even to the detriment of their already diminished capacity. When health professionals did not collaborate with non-health support services, they may have been perceived by others to lack authority or value. Bojovic and Geiger [

48] note that under-recognition of support services can reinforce inequitable systems.

4.2.3. Knowing Family Capacity

Complexity and Fluctuation of Family Capacity

All stakeholder groups identified family capacity as a critical factor influencing engagement in Family-Centred Care. Importantly, our research illustrates that capacity, particularly that of the family, is complex and constantly fluctuating. Families emphasised their capacity was not a fixed state but varied due to several interconnected, internal and external factors, meaning their ability to engage with services changed over time.

One of the most significant contributors to fluctuating family capacity was the cumulative burden of caregiving. The physical, emotional, and financial demands of caregivers have been well documented in past literature and shown to negatively impact caregivers’ quality of life and well-being [

49,

50]. Families in this research described how caregiving responsibilities affected their sleep, mental health, relationships, and finances, leading to ongoing stress and exhaustion, reducing their capacity for additional tasks. As reported by Holland [

51], caregiving burdens are often invisible to others outside the family unit, contributing to families’ feelings of isolation and shaping many aspects of their daily lives.

In addition to the profound emotional toll of caregiving responsibilities, many parents also described the impact on their careers, which in turn affected their overall capacity. Many caregivers had reduced their formal work hours or stepped into full-time caregiving roles, the shift from employment into unpaid caregiving inevitably resulting in financial strain. This further compounded the pressure for families to advocate for adequate funding and resources to support their child. Our findings align with reports that caregivers of children with genetic conditions are more likely to leave the workforce than other caregivers, primarily due to the complexity of their caregiving responsibilities [

52]. Studies have detailed the financial consequences of unpaid caregiving across a range of age groups and health conditions [

53,

54,

55], and UNICEF [

39] notes that disability-associated costs and lost earning opportunities mean that families with disabled children have increased vulnerability to poverty.

Our research affirms an approach proposed by King et al. [

56] describing a continuum of family-oriented services with an emphasis on understanding families’ needs and enhancing their capacity. It is essential that service providers develop a deep understanding of each family’s capacity, the factors that influence it, recognise that what is possible for a family one week may not be achievable the next, and adjust responsively to these changing circumstances. Phenomenological research by Cook et al. [

57] with parents caring for disabled children supports our findings. They emphasise the need for professional awareness of psychological factors and families’ lived experiences to enhance empathy-driven Family-Centred Care and suggest a structured framework to better understand what influences families’ comfort and well-being.

Divergent Perceptions of Family Capacity

Our research identified a clear mismatch between service providers’ perceptions of family capacity and families’ lived realities. Service providers in this research often characterised families as overwhelmed or facing hardship, yet their understanding of family capacity frequently lacked the depth and specificity conveyed by families themselves. Families described additional challenges, including daily practical demands, exhaustion, stress, guilt, and emotional distress, which significantly impacted their ability to engage with services. Notably, families in our research identified several factors influencing their capacity that were not mentioned at all by service providers, including past trauma, personal relationship breakdowns, sleep deprivation, and advocacy fatigue.

Families in our study also drew attention to the cumulative effect of system navigation, the ‘time costs’ related to managing fragmented care. These findings echo reports from the Centre for Innovation and Value Research [

58] and reinforce the importance of providers understanding the invisible work families undertake. In our study, providers with lived experience offered the most empathetic insights into these complexities, suggesting that reflective practice and practice informed by such experience may help bridge this gap.

Our findings highlight the importance of providers developing a deep appreciation for the wide range of emotional and practical burdens that shape family capacity. While many of these burdens are beyond the control of individual providers, steps can still be taken to alleviate some if providers are aware of them and, at the very least, to avoid unintentionally adding to the family’s burden. When there is a disconnect between what health professionals expect families to do and what families are reasonably able to manage, this reflects a mis-conceptualisation of Family-Centred Care. Such mismatch can undermine collaboration, deplete family capacity, and risk disengagement.

Unrealistic Expectations Due to Lack of Knowingness

Our research highlighted a tension in the broad assumption that ‘parents are the experts on their child’. While intended to empower families, this notion often shifted responsibility onto parents without adequate consideration of their knowledge or capacity. Cameron [

59] similarly highlighted that professionals cannot simply transfer power to parents when the very system they operate within actively works to disempower them. In this research, therapy providers recognised caregiver ‘expertise’ as a key family characteristic and intended this recognition to convey respect. However, without a deeper understanding of each family’s context and limits, this assumption sometimes placed unrealistic expectations on parents to independently manage complex healthcare decisions beyond their capacity, reflecting a lack of mutual knowingness.

4.3. Respond—Responding to Systemic Barriers and Family Capacity

Trusted relationships and mutual knowingness are essential for understanding the systemic and practical constraints that shape family capacity and a provider’s ability to deliver care. This understanding enables providers to respond in meaningful ways that support trust and engagement, even within systemic limitations.

4.3.1. Responding to Systemic Barriers Through Advocacy and Health Navigation

As seen in this research, the need for advocacy and navigation work often arose in direct response to unmet needs and poor systemic responsiveness. Families deeply valued providers’ advocacy efforts, especially when navigating multiple service providers or during times of additional stress, such as transitions between services and increasing complexity of health needs. The advocacy ability of service providers varied and was largely dependent on their available time and knowledge regarding other providers, which in turn was shaped by their own service limitations. These findings highlight a tension between the central aims of Family-Centred Care and the systemic realities of service delivery. While advocacy is implicit in principles such as partnership, empowerment, and collaboration [

10], advocacy by professionals remains inconsistent and dependent on the service model, funding environment, and individual provider capacity.

In response to systemic complexity, health navigation has emerged as a more structured approach to support. In our research, families were not specifically asked about their interaction with health navigators; however, it appeared that in general this support was lacking. In theory, navigators are integrated into the patient’s healthcare team to provide continuity and reduce barriers in complex service systems, yet their role and responsibilities are distinct from all other providers [

60]. Whilst formal health navigator services exist in New Zealand, they are less well developed and implemented for disabled people [

61].

In New Zealand, web-based platforms like Healthify aim to fill the health navigation gap by offering online health and resource guidance [

62]. However, families are still required to proactively seek out, interpret, and act on this information. This highlights the continuing need for system-level solutions that enable both families and providers to engage more effectively and reduce avoidable stress.

4.3.2. Responding to Capacity

Responsive provision of services must align with each family’s capacity and address the factors that may influence their ability to engage, both currently and in the future. In our research, a comprehensive, iterative understanding of family capacity, including strengths, limitations, and family circumstances, enabled therapists to tailor meaningful therapies and to offer preferred locations, modelled behaviours, and practical support. By adjusting service plans and expectations to align with family realities, providers can help reduce the emotional and logistical burdens placed on families.

Responding to mutual knowingness must be a two-way process, where providers not only seek to understand a family’s capacity but also acknowledge, reflect on, and share their own service limitations. These findings are supported by a qualitative study by Lansing et al. [

63], which explored facets of trust-building within community health partnerships and highlighted the importance of relationships that embodied values of trustworthiness and transparency. Our research reinforces the view that by encouraging families to share openly and by being transparent in return, expectations can be realistically aligned, trust is promoted, and providers can ensure that support is practical and achievable.

4.3.3. Responding Through Effective Communication

Transparency between services and families requires open and honest communication, which, as discussed in earlier sections, plays a crucial role in bridging gaps created by systemic barriers and in fostering mutual knowingness. This is critical since existing literature shows that suboptimal communication in healthcare settings can have dire consequences for patients, including reduced access to care, adverse health outcomes, and unmet family expectations [

64,

65].

Communication systems are another important consideration for service providers. Avari et al. [

33] found that tailoring communication methods to align with family preferences improves information-sharing opportunities and promotes family engagement. However, the choice of communication methods must be determined on a case-by-case basis in response to the family’s preferences and capacity. As indicated by some service providers in this research, digital inequities persist within New Zealand, and not all families have access to reliable internet or devices.

4.3.4. Constraints of Service Responsiveness

Service providers described systemic constraints that limited their ability to engage with families and deliver services, with support services often disproportionately affected by disengagement due to families’ reduced capacity and challenges with visibility. Advocacy was recognised as a potential response to diminished family capacity. However, the challenges faced by both families and providers in fulfilling advocacy roles, within the context of systemic constraints and service limitations, raise a critical question of whether this role is realistically achievable. When services are aware of a family’s limitations but do not respond, they risk potentially reinforcing inequities and jeopardise trusted relationships. As seen in our study, when providers understand a family’s capacity and adapt their approach through flexible planning and simplified communication, outcomes improve. However, knowing what is required is not enough; effective implementation requires systemic support, provider training, and access to resources. Without these, the gap between knowing and responsiveness persists, highlighting the value of even small, individual-level changes as a meaningful starting point.

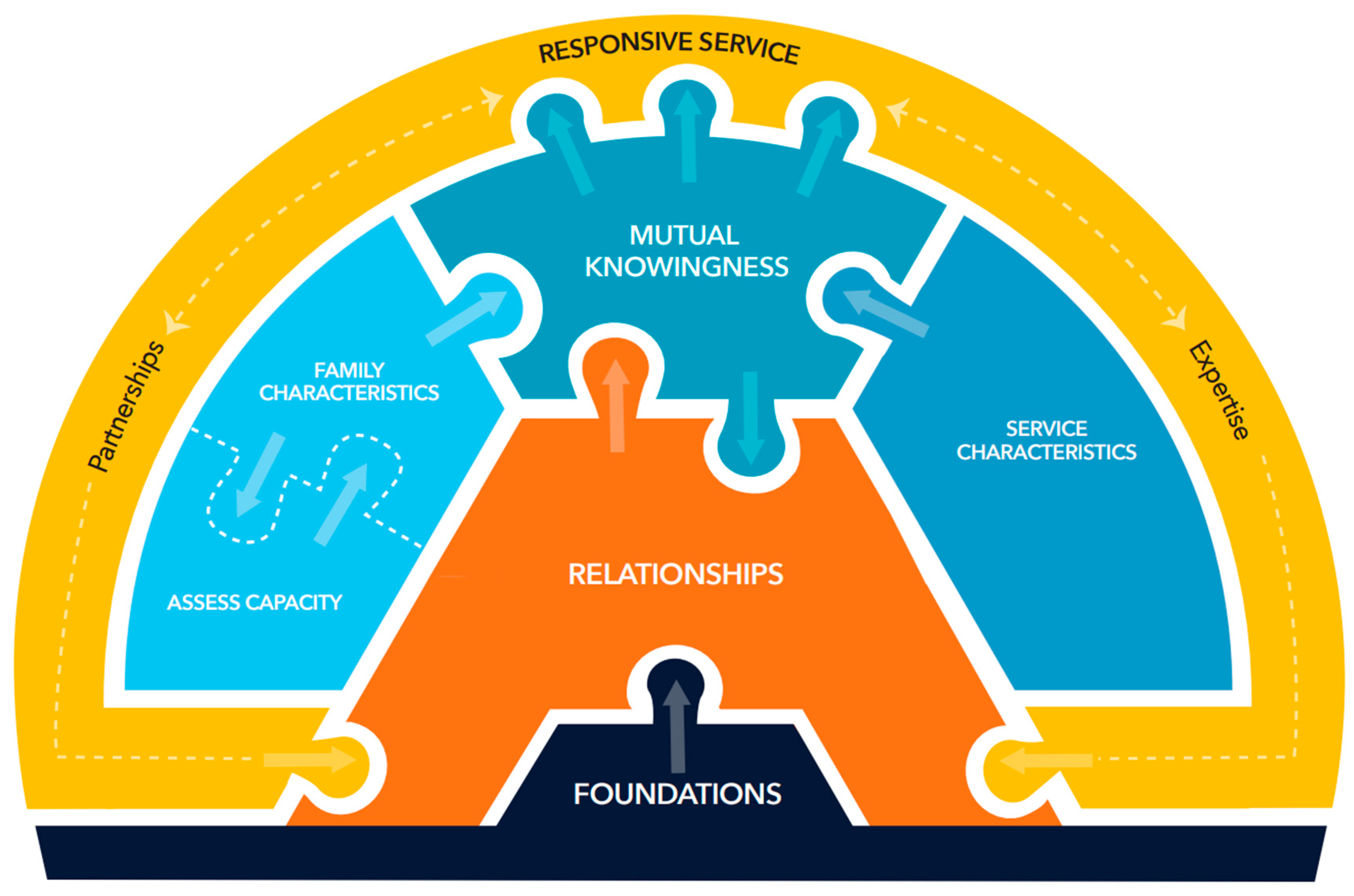

5. Clinical Implications

The findings from our research are presented as a new service delivery model, the Relate-Know-Respond Model (

Figure 4). This model is intended to guide service providers to optimise relationships and mutual knowingness to promote responsive Family-Centred service delivery for disabled young people and their families. Our model supports the well-established understanding that relationships and partnerships are central to Family-Centred Care and service delivery [

66]. In addition, we emphasise the importance of ‘knowingness’, which encapsulates the mutual understanding of capacity, roles, and systemic realities as a key factor influencing relationships and responsive care. The process of developing the Relate-Know-Respond clinical model and mapping it to practice is outlined in the

Appendix A (

Figure A1).

As seen in

Figure 4, relationships, and the building blocks of relationships, are at the heart of the model and therefore must be prioritised by service providers. As our research shows, trusting relationships can be built from simple foundations and nurtured through thoughtful intentional care. Strong relationships are fostered through welcoming, safe, and non-judgemental environments; culturally responsive care; effective communication and collaboration; active listening; and by allowing time and space for family storytelling. Relationships influence the process of ‘knowingness’, with strong relationships enabling service providers to learn about families and to share elements of their own service in return. In turn, a strong sense of mutual knowingness feeds back to reinforce the trust and ongoing development essential for effective family-professional relationships.

Mutual knowingness is dynamic and collaborative and describes the extent to which each group understands or ‘knows’ each other’s key characteristics. Since the priorities of families and service providers are determined by their key characteristics, mutual knowingness is essential for aligning services with families’ needs. Providers must have a strong awareness of their own characteristics and limitations and must clearly communicate the systemic barriers within which they operate to families. If service providers don’t understand their own capacity and/or that of the family, there is the potential for misunderstandings and unrealistic expectations, which may result in mistrust, conflict, and disengagement.

As such, service providers must understand families’ key characteristics and, most critically, have an up-to-date understanding of their fluctuating capacity. It is the service providers’ responsibility to find ways to connect with families, at their pace and within their capacity, and they must carry out regular and intentional check-ins to better understand families’ current realities. Knowingness allows providers to identify strategies that are both practical and achievable within the confines of broader systemic barriers while still being tailored to meet family needs. Effective ‘mutual knowingness’ feeds back to further shape the family-professional relationship whilst also having a direct impact on the providers’ responsive service.

Mutual knowingness contributes to the provider’s responsive service in two key domains aligned with Family-Centred Care principles. Namely, meaningful family-professional partnerships and the application of professional expertise. Providers must leverage their mutual knowingness to support families’ capacity through meaningful family-professional partnerships. Provider actions may include advocacy and service navigation, as well as Family-Centred Care processes, including shared decision-making, communication, collaboration, transparency, honesty, and continuity of care.

Professional expertise is a key element of responsive service provision. Service providers should support families with practical strategies focused on alleviating emotional and logistical concerns, such as written and videoed programmes, physical equipment, accessible resources, and planning tools. Our research suggests that provider advice should focus on enjoyable and manageable therapies built into daily routines. In addition, education, support with goal setting, future planning tools, and forecasting strategies may help families to anticipate developmental changes and mitigate concerns. When partnership and expertise strategies are implemented effectively, these domains reinforce one another and contribute to stronger family-professional relationships, bringing the process full circle. Each provider will also bring their own unique strengths to this process and operate within a different contextual environment, further shaping how these strategies are applied in practice.

Table 4 outlines actionable strategies for delivering responsive service, tailored to both the characteristics and capacity of families and the service context. The first column maps the key domains of the Relate-Know-Respond Model. The second column outlines clinical strategies aligned with each domain, highlighting focus areas for service providers. The third column lists suggested actions to operationalise each strategy, and the fourth column offers a selection of tools to support these actions in practice. Note that the tools do not align line-for-line with the suggested actions, as multiple tools may be relevant across different strategies or actions. Service providers are encouraged to consider which tools best fit their context and goals and to proactively search for additional tools to support the clinical strategies.

6. Strengths and Limitations

This research offers diverse and varied perspectives from different stakeholders of paediatric healthcare for disabled young people. The number of participants and rigorous qualitative data collection and analysis methods allowed for systematic and in-depth exploration of experiences and perceptions of all stakeholders. The clinical strategies and tools presented in this study may also hold relevance for professionals across other disciplines supporting disabled children and their families. Although the study was undertaken in New Zealand, the findings are likely to be indicative of situations elsewhere, though the presence of different structures and funding models means they may take a different form.

While this study included a range of therapy professionals, its scope did not extend to other key healthcare providers. As a result, the interdisciplinary perspective does not reflect the views of professionals such as nurses, paediatricians, or social workers, whose insight may have offered additional depth. Similarly, although young people were included, the number was small relative to adult participants; therefore, future research is needed to fully understand disabled youth’s experiences. Recruitment was primarily through existing networks and social media, which may favour more engaged individuals and potentially exclude more marginalised voices. Despite limitations, our research provides practical and relevant findings and provides a new model for service providers to understand and enhance implementation of Family-Centred Care.

7. Future Research

Two key areas for future research are evident. First, exploring the application of the Relate-Know-Respond Model and its associated clinical strategies and tools with therapeutic service providers, as included in this study. Second, examining how key themes identified here, such as knowingness and capacity, are perceived and experienced by professionals from other disciplines, including nursing and medicine. Broadening this exploration may help to strengthen interdisciplinary understanding and support for disabled children and their families and identify additional opportunities for meaningful engagement.

Play-based activities that focus on outcomes meaningful to families, such as having fun, making friends, and fostering social connections, represent a promising area for future research. Play represents a powerful and often underutilised avenue for achieving Family-Centred Care. Such activities not only align with what families value for their children but also bridge gaps between therapists and families. Framing goals around play can provide an accessible and meaningful start for collaborative goal setting, reinforcing core Family-Centred Care principles of shared decision-making and respect for family priorities.

Finally, further research is warranted to understand the influence of the medical model’s antiquated prioritisation of measurable outcomes, which marginalises families’ intuitive feelings and experiences with play.

8. Conclusions

Our research reinforces well-established concepts related to family-professional relationships and the importance of collaboration and partnerships in Family-Centred Care. We also offer novel insights into the concept of mutual knowingness and the importance of understanding family capacity. Our new Relate-Know-Respond Model is designed to support service providers, both in New Zealand and internationally, to work with families to enhance Family-Centred Care. Our model highlights that, due to the often-underappreciated fluctuating complexity of capacity, ongoing understanding and assessment are essential for service providers to truly know each family. Mutual knowingness both shapes and strengthens relationships, serving as a key step toward delivering responsive services that foster genuine partnerships and provide support through professional expertise. The knowingness process is circular, with each element building on and influencing the next. Sound knowledge about every element is critical since when one area is weak, the others are likely to falter as well.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C. and M.P.; methodology, L.C. and M.P.; software, L.C.; validation, L.C. and M.P.; formal analysis, L.C.; investigation, L.C.; data curation, L.C.; writing—original draft preparation, L.C.; writing—review and editing, L.C., L.H., C.F. and M.P.; supervision, L.H., C.F. and M.P.; project administration, L.C.; funding acquisition, L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Physiotherapy New Zealand Paediatric Special Interest Group (Professional Development Award 2023), Physiotherapy New Zealand Neurological Special Interest Group (Academic Grant 2023), and The International Organisation of Physiotherapists in Paediatrics (2023 IOPTP Research Grant).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the University of Otago (H23/014, 3 March 2023). This study was also approved by the Ngāi Tahu Research Consultation Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

Shelley Darren Design for graphics support. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Disability Language/Terminology Positionality Statement

We adopt a social–ecological lens, viewing disability as arising from interactions between people and their environments, and recognising that societal and systemic factors can disable or enable participation. Reflecting this stance and participants’ frequent social-model perspectives, we use identity-first language (e.g., ‘disabled children’) throughout, while respecting individuals’ stated preferences.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Semi-structured interview and focus group guides.

Table A1.

Semi-structured interview and focus group guides.

Service Users—

Semi-Structured Interview Topics | Example Question(s) |

| Experiences of healthcare and other services | Could you tell me about the healthcare professionals you use/have seen?

Do you access any other organisations—such as support services,

extra-curricular activities?

Can you describe a time when your family started with a new service provider that went really well? What were the best features? |

Family-Centred Care principles-

Relationships | Do you feel like the health professionals/support services really understand your child’s needs and what is most important to you? How do you know? |

| Collaboration | Can you describe the ways that different people that help your child work collaboratively with others? |

| Communication | How do you communicate with different people supporting you? What works best? |

| Co-design of services for the child | Have you been asked for feedback on how therapies (particularly at home) are going, and have things changed based on your feedback? |

| Meaningful outcomes for the child and family | How do you prioritise what is most important to your child?

What is the most important thing for your child/family to work towards with health professionals? |

| General follow-up questions | |

Service Providers (Therapists)—

Semi-Structured Interview Topics | Example Question(s) |

| Background and rapport building | |

| Experiences, knowledge and perceptions of families with disabled children | Could you tell me about your experiences working with children with disabilities?

Can you describe these children in some detail? |

| Defining and implementing family-centred healthcare services | Are there any guiding principles or frameworks that you follow?

How would you describe the term Family-Centred Care in your own words?

Do you work collaboratively with other professionals? |

| Experiences, knowledge and perceptions of barriers and facilitators to healthcare services for children with disabilities | In your experience of working with children and families, have you identified any barriers or facilitators for families to access services? |

| | From your experience, what are the main things that you feel families are seeking from their healthcare providers—what could be done better? |

| General follow-up questions | |

Service Providers (Advisors)—

Semi-Structured Focus Group Topics | Example Question(s) |

| Background and rapport building | |

| Healthcare service delivery review | In your area of work, what would you say guided, or what philosophy guides you, in how you interact with disabled children? Can you describe these children in some detail? |

| Family-Centred Care | Tell me how you use Family-Centred Care in your work? Are there elements of your service that you consider to be good examples of Family-Centred Care? How would you describe the term Family-Centred Care in your own words?

How do you think families feel about being incorporated into your sessions/care? |

| General follow-up questions | |

Figure A1.

Process of developing the Relate-Know-Respond Model and its translation to practice.

Figure A1.

Process of developing the Relate-Know-Respond Model and its translation to practice.

References

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Persons with Disabilities; The United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2007; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Seen, Counted, Included: Using Data to Shed Light on the Well-Being of Children with Disabilities. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/children-with-disabilities-report-2021/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Stats NZ. Disabilities Survey: 2013. Available online: https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/disability-survey-2013 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Ministry of Health. New Zealand Health Survey. Available online: https://www.health.govt.nz/nz-health-statistics/surveys/new-zealand-health-survey (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Almasri, N.A.; An, M.; Palisano, R.J. Parents’ perception of receiving family-centered care for their children with physical disabilities: A meta-analysis. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2018, 38, 427–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee on hospital care institute for patient-family-centered care. Patient- and family-centered care and the pediatrician’s role. Pediatrics 2012, 129, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, G.; Chiarello, L. Family-centered care for children with Cerebral Palsy: Conceptual and practical considerations to advance care and practice. J. Child Neurol. 2014, 29, 1046–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, L. What is “family-centred care”? Eur. J. Pers. Centered Healthc. 2015, 3, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokorelias, K.M.; Gignac, M.A.M.; Naglie, G.; Cameron, J.I. Towards a universal model of family centered care: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, D.Z.; Houtrow, A.J.; Arango, P.; Kuhlthau, K.A.; Simmons, J.M.; Neff, J.M. Family-centered care: Current applications and future directions in pediatric health care. Matern Child Health J. 2012, 16, 297–305. Available online: https://rdcu.be/eAmt2 (accessed on 10 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Carrington, L.; Hale, L.; Freeman, C.; Qureshi, A.; Perry, M. Family-centred care for children with biopsychosocial support needs: A scoping review. Disabilities 2021, 1, 301–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uniacke, S.; Browne, T.K.; Shields, L. How should we understand family-centred care? J. Child Health Care 2018, 22, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guralnick, M.J. Why early intervention works: A systems perspective. Infants Young Child. 2011, 24, 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, P.; Puelle, F.; Barría, R.M. Perception of the quality of physiotherapy care provided to outpatients from primary health care in Chile. Eval. Health Prof. 2020, 43, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camden, C.; Mulligan, H.; Cinar, E.; Gauvin, C.; Berbari, J.; Nugraha, B.; Gutenbrunner, C. Perceived strengths and weaknesses of paediatric physiotherapy services: Results from an international survey. Physiother. Res. Int. 2023, 28, 1358–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Blamires, J.; Foster, M. The impact of policies and legislation on the structure and delivery of support services for children with Cerebral Palsy and their families in Aotearoa New Zealand: A professional perspective. Nurs. Prax. Aotearoa New Zealand 2022, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zyl, C.; Badenhorst, M.; Hanekom, S.; Heine, M. Unravelling ‘low-resource settings’: A systematic scoping review with qualitative content analysis. BMJ Glob Health 2021, 6, e005190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Health Workforce. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-workforce?utm (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Craig, P.; Dieppe, P.; Macintyre, S.; Michie, S.; Nazareth, I.; Petticrew, M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008, 337, 979–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Physiotherapy New Zealand. Collaborative Healthcare Model Person and Whānau Centred Care. Available online: https://pnz.org.nz/pwcc/Attachment?Action=Download&Attachment_id=1032 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Green, J.; Thorogood, N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research, 2nd ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, P.; Stewart, K.; Treasure, E.; Chadwick, B. Methods of data collection in qualitative research: Interviews and focus groups. Br. Dent. J. 2008, 204, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. ICF: International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- McLeroy, K.R.; Bibeau, D.; Steckler, A.; Glanz, K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ. Q. 1988, 15, 351–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoom Video Communications, Inc. Zoom Meetings; Zoom Video Communications, Inc.: San Jose, CA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://zoom.us (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft Excel for Microsoft 365, version 2305; Microsoft Corporation: Redmond, WA, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.microsoft.com/microsoft-365/excel (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- AISense, Inc. Otter.ai.; AISense, Inc.: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2025; Available online: https://otter.ai (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Houtrow, A.J. Family-centered care and shared decision making in rehabilitation medicine. In Principles of Rehabilitation Medicine; Mitra, R., Ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century; National Academies Press: Washington, WA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, D.; Scarinci, N.; Hickson, L. The nature of patient- and family-centred care for young adults living with chronic disease and their family members: A systematic review. Int. J. Integr. Care 2018, 18, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valaitis, R.; Meagher-Stewart, D.; Martin-Misener, R.; Wong, S.T.; MacDonald, M.; O’Mara, L.; Baumann, A.; Brauer, P.; Green, M.; Kaczorowski, J.; et al. Organizational factors influencing successful primary care and public health collaboration. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avari, P.; Hamel, E.; Schachter, R.E.; Hatton-Bowers, H. Communication with families: Understanding the perspectives of early childhood teachers. J. Early Child. Res. 2023, 21, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katkin, J.P.; Kressly, S.J.; Edwards, A.R.; Perrin, J.M.; Kraft, C.A.; Richerson, J.E.; Tieder, J.S.; Wall, L.; Alexander, J.J.; Flanagan, P.J.; et al. Guiding principles for team-based pediatric care. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20171489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. WHO Releases New Guidance on Monitoring the Social Determinants of Health Equity. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/19-02-2024-who-releases-new-guidance-on-monitoring-the-social-determinants-of-health-equity?utm (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- World Health Organization. Tracking Universal Health Coverage: 2017 Global Monitoring Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Goodyear-Smith, F.; Ashton, T. New Zealand health system: Universalism struggles with persisting inequities. Lancet 2019, 394, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allshouse, C.; Comeau, M.; Rodgers, R.; Wells, N. Families of children with medical complexity: A view from the front lines. Pediatrics 2018, 141, S195–S201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF Europe and Central Asia Regional Office. Reducing Poverty Through Support for Children with Disabilities and Their Families. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/eca/stories/reducing-poverty-through-support-children-disabilities-and-their-families (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Sharma, K.M.; Jones, P.B.; Cumming, J.; Middleton, L. Key elements and contextual factors that influence successful implementation of large-system transformation initiatives in the New Zealand health system: A realist evaluation. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocks, S.; Berntson, D.; Gil-Salmerón, A.; Kadu, M.; Ehrenberg, N.; Stein, V.; Tsiachristas, A. Cost and effects of integrated care: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2020, 21, 1211–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calciolari, S.; Ortiz, L.G.; Goodwin, N.; Stein, V. Validation of a conceptual framework aimed to standardize and compare care integration initiatives: The project INTEGRATE framework. J. Interprof. Care 2022, 36, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, D.; Horn, M. Challenges to health system sustainability. Intern. Med. J. 2022, 52, 1300–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redhead, G.; Lynch, R. The unfairness of place: A cultural history of the UK’s ‘postcode lottery’. Health Place 2024, 90, 103301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Starting Strong V: Transitions from Early Childhood Education and Care to Primary Education; OECD: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]