Augmentative and Alternative Communication Strategies for Learners with Diverse Educational Needs in African Schools: A Qualitative Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

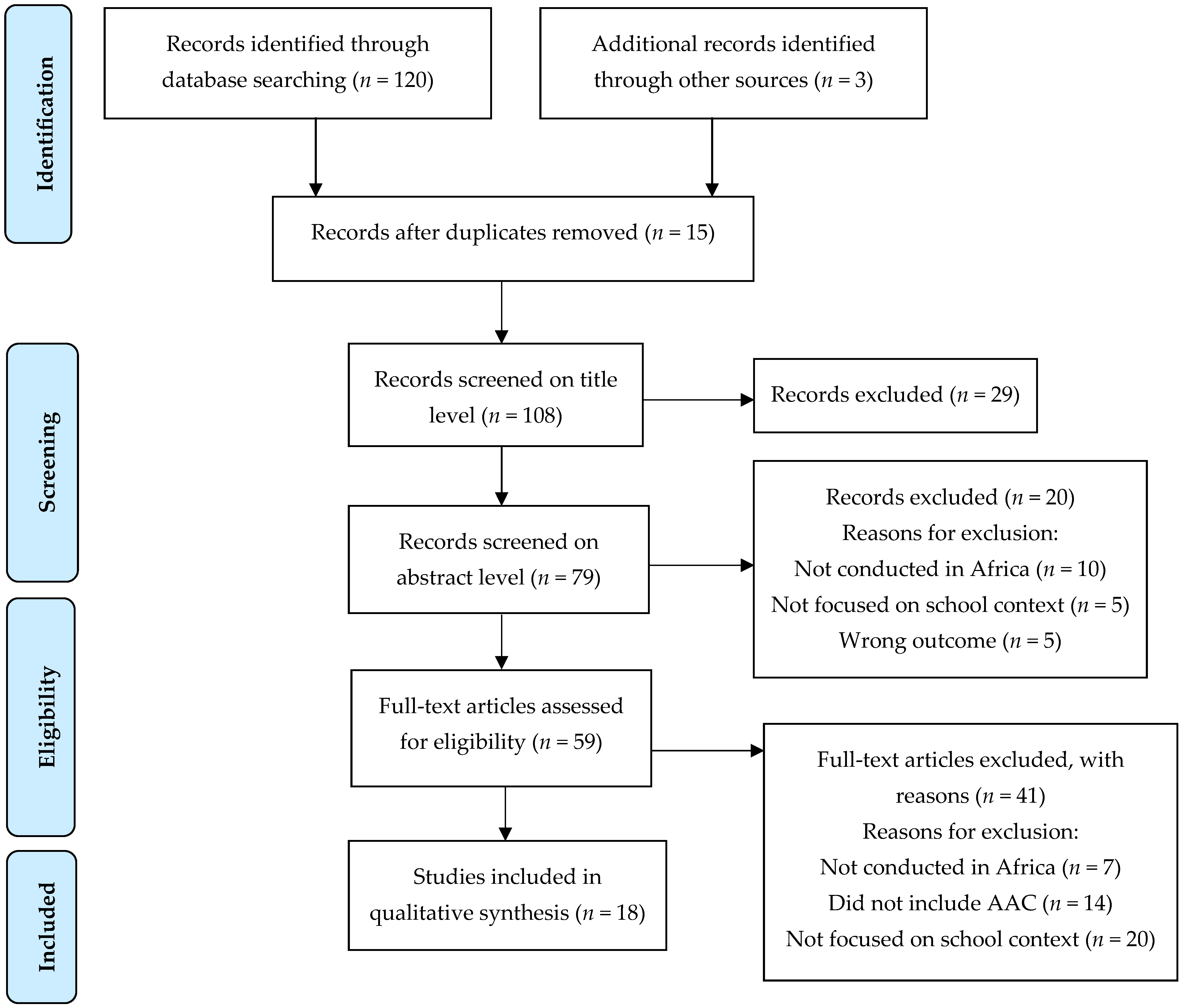

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identifying Relevant Studies and Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection, Search Terms, and Database Searches

- Studies on human participants and reviews.

- Material published between 1980 and July 2024, as the inception of the field of AAC was in 1980 [27].

- Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method research designs were included.

- Studies published in English.

- Peer-reviewed gray literature (published conference proceedings and reports were included, while book chapters, dissertations, websites, and newspapers were excluded due to the absence of peer review of unpublished literature for the qualitative literature review’s pre-determined inclusion criteria) [28].

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

- The authors familiarized themselves with the data and focused on data reduction through triangulation.

- The authors hand-coded the data.

- Themes were determined through inductive coding (a bottom–up approach using data content to determine codes).

- The identified themes were reviewed.

- Themes were defined and named.

- The thematic analysis process concluded with the production of a report.

3. Results

3.1. Summarizing and Reporting the Data

3.1.1. Demographics

3.1.2. Reported Strategies

AAC Strategy or System

Classroom Instruction Strategies

Learning Process

Participant Proficiency

3.1.3. Maintenance of AAC Use and Outcomes

3.2. Trustworthiness

4. Discussion

4.1. Demographics

4.2. Reported Strategies

4.2.1. AAC Strategy or System

4.2.2. Classroom Instruction Strategies

4.2.3. Learning Process

4.2.4. Participant Proficiency

4.3. Maintenance and Outcomes

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAC | Augmentative and Alternative Communication |

| ADHD | Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder |

| CCN | complex communication needs |

| CP | cerebral palsy |

| OT | occupational therapist |

| PCS | Picture Communication Symbols |

| PECS | Picture Exchange Communication System |

| PT | physiotherapist |

| SLT | speech–language therapist |

| UNCRPD | United Nations Charter for the Rights of Persons with Disabilities |

References

- Creer, S.; Enderby, P.; Judge, S.; John, A. Prevalence of People Who Could Benefit from Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) in the UK: Determining the Need. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2014, 51, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichle, J.; Simacek, J.; Wattanawongwan, S.; Ganz, J. Implementing Aided Augmentative Communication Systems with Persons Having Complex Communicative Needs. Behav. Modif. 2019, 43, 841–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simacek, J.; Pennington, B.; Reichle, J.; Parker-McGowan, Q. Aided AAC for People with Severe to Profound and Multiple Disabilities: A Systematic Review of Interventions and Treatment Intensity. Adv. Neurodev. Disord. 2018, 2, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacker, R.E.; Meadan, H.; Terol, A.K. Siblings Supporting the Social Interactions of Children Who Use Augmentative and Alternative Communication. Am. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2023, 32, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tönsing, K.M.; Dada, S. Teachers’ Perceptions of Implementation of Aided AAC to Support Expressive Communication in South African Special Schools: A Pilot Investigation. Augment. Altern. Commun. 2016, 32, 282–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beukelman, D.; Light, J. Augmentative and Alternative Communication: Supporting Children and Adults with Complex Communication Needs; eTextbooks for Students; Paul H Brookes Publishing: Towson, MD, USA, 2020; p. 588. [Google Scholar]

- Kuyler, A.; Johnson, E.; Bornman, J. Unaided Communication Behaviours Displayed by Adults with Severe Cerebrovascular Accidents and Little or No Functional Speech: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2022, 57, 403–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornman, J.; Waller, A.; Lloyd, L.L. Background, Features, and Principles of AAC Technology. In Principles and Practices in Augmentative and Alternative Communication; Routledge: London, UK, 2024; pp. 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- Romski, M.; Sevcik, R.A.; Barton-Hulsey, A.; Whitmore, A.S. Early Intervention and AAC: What a Difference 30 Years Makes. Augment. Altern. Commun. 2015, 31, 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohue, D.; Bornman, J. The Challenges of Realising Inclusive Education in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Educ. 2014, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terblanche, C.; Pascoe, M.; Harty, M. Challenges, Perceptions and Implications of AAC Use in South African Classrooms: An Exploratory Focus Group Study. Child Lang. Teach. Ther. 2022, 41, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldabas, R. Barriers and Facilitators of Using Augmentative and Alternative Communication with Students with Multiple Disabilities in Inclusive Education: Special Education Teachers’ Perspectives. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2021, 25, 1010–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dada, S.; Murphy, Y.; Tönsing, K. Augmentative and Alternative Communication Practices: A Descriptive Study of the Perceptions of South African Speech-Language Therapists. Augment. Altern. Commun. 2017, 33, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norrie, C.S.; Waller, A.; Hannah, E.F. Establishing Context: AAC Device Adoption and Support in a Special-Education Setting. ACM Trans. Comput. Hum. Interact. 2021, 28, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Fonte, M.A.; Boesch, M.C.; Young, R.D.; Wolfe, N.P. Communication System Identification for Individuals with Complex Communication Needs: The Need for Effective Feature Matching. In International Review of Research in Developmental Disabilities; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 57, pp. 171–228. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD); Retrieved from UN Treaty Collection; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, E.D.; Kurin, K.; Atkins, K.L.; Cook, A. Identifying Implementation Strategies to Increase Augmentative and Alternative Communication Adoption in Early Childhood Classrooms: A Qualitative Study. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 2023, 54, 1136–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kangas, M.; Antti, K.; Leena, K. A qualitative literature review of educational games in the classroom: The teacher’s pedagogical activities. Teach. Teach. 2017, 23, 451–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacono, T.; Douglas, S.N.; Garcia-Melgar, A.; Goldbart, J. A Scoping Review of AAC Research Conducted in Segregated School Settings. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2022, 120, 104141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttiah, N.; Gormley, J.; Drager, K.D.R. A scoping review of Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) interventions in Low-and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs). Augment. Altern. Commun. 2022, 38, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dada, S.; Wylie, K.; Marshall, J.; Rochus, D.; Bampoe, J.O. The Importance of SDG 17 and Equitable Partnerships in Maximising Participation of Persons with Communication Disabilities and Their Families. Int. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2023, 25, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kestenbaum, B. Population, Exposure, and Outcome. In Epidemiology and Biostatistics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Basic Education (DBE). South African Schools Act 84. Gov. Gaz. Repub. S. Afr. 1996, 377, 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- McDougall, J.; Wright, V.; Rosenbaum, P. The ICF Model of Functioning and Disability: Incorporating Quality of Life and Human Development. Dev. Neurorehabilit. 2010, 13, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, H.; Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.M.; McInerney, P.; Soares, C.B.; Parker, D. An Evidence-Based Approach to Scoping Reviews. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2016, 13, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNaughton, D.; Light, J. What We Write About When We Write About AAC: The Past 30 Years of Research and Future Directions. Augment. Altern. Commun. 2015, 31, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benzies, K.M.; Premji, S.; Hayden, K.A.; Serrett, K. State-of-the-Evidence Reviews: Advantages and Challenges of Including Grey Literature. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2006, 3, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco, D.; Altman, D.; Moher, D.; Boutron, I.; Kirkham, J.J.; Cobo, E. Scoping Review on Interventions to Improve Adherence to Reporting Guidelines in Health Research. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avidnote. Avidnote (Version 1) [Computer Software]. Avidnote. Available online: https://avidnote.com/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Can I Use TA? Should I Use TA? Should I Not Use TA? Comparing Reflexive Thematic Analysis and Other Pattern-Based Qualitative Analytic Approaches. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2021, 21, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alant, E.; Moolman, E. Blissymbol Learning as a Tool for Facilitating Language and Literacy Development. S. Afr. J. Educ. 2001, 21, 339–343. [Google Scholar]

- Alant, E.; Zheng, W.; Harty, M.; Lloyd, L. Translucency Ratings of Blissymbols over Repeated Exposures by Children with Autism. Augment. Altern. Commun. 2013, 29, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornman, J.; Alant, E. Nonspeaking Children in Schools for Children with Severe Mental Disabilities in the Greater Pretoria Area: Implications for Speech-Language Therapists. S. Afr. J. Commun. Disord. 1996, 43, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dada, S.; Granlund, M.; Alant, E. A Discussion of Individual Variability in Activity-Based Interventions Using the Niche Concept. Child Care Health Dev. 2007, 33, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dada, S.; Huguet, A.; Bornman, J. The Iconicity of Picture Communication Symbols for Children with English Additional Language and Mild Intellectual Disability. Augment. Altern. Commun. 2013, 29, 360–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiger, M. Using Cultural Resources to Build an Inclusive Environment for Children with Severe Communication Disabilities: A Case Study from Botswana. Child. Geogr. 2010, 8, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heslop, J.; Mophosho, M. Communication Strategies Used by Specialised Preschool Teachers for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder in South Africa. Allied Health Sch. 2021, 2, 20–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.; Bornman, J.; Tönsing, K.M. An Exploration of Pain-Related Vocabulary: Implications for AAC Use with Children. Augment. Altern. Commun. 2016, 32, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laher, Z.; Dada, S. The Effect of Aided Language Stimulation on the Acquisition of Receptive Vocabulary in Children with Complex Communication Needs and Severe Intellectual Disability: A Comparison of Two Dosages. Augment. Altern. Commun. 2023, 39, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilienfeld, M.; Alant, E. The Social Interaction of an Adolescent Who Uses AAC: The Evaluation of a Peer-Training Program. Augment. Altern. Commun. 2005, 21, 278–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, A.; Bornman, J. Using Key-Word Signing to Support Learners in South African Schools: A Study of Teachers’ Perceptions. Augment. Altern. Commun. 2022, 38, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naudé, T.; Dada, S.; Bornman, J. The Effect of an Augmented Input Intervention on Subtraction Word-Problem Solving for Children with Intellectual Disabilities: A Preliminary Study. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2022, 69, 1988–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tönsing, K.M.; Dada, S.; Alant, E. Teaching Graphic Symbol Combinations to Children with Limited Speech During Shared Story Reading. Augment. Altern. Commun. 2014, 30, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, J.; Geiger, M. The Effectiveness of the Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): A South African Pilot Study. Child Lang. Teach. Ther. 2010, 26, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uys, C.J.E.; Harty, M. Narrowing the Gap: Using Aided Language Stimulation (ALS) in the Inclusive Classroom. S. Afr. J. Occup. Ther. 2007, 37, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Bijl, C.; Alant, E.; Lloyd, L. A Comparison of Two Strategies of Sight Word Instruction in Children with Mental Disability. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2006, 27, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Niekerk, K.; Tönsing, K. Eye Gaze Technology: A South African Perspective. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2015, 10, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyngäs, H.; Kääriäinen, M.; Elo, S. The Trustworthiness of Content Analysis. In The Application of Content Analysis in Nursing Science Research; Kyngäs, H., Mikkonen, K., Kääriäinen, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, C.; Dada, S. The Effect of AAC Training Programs on Professionals’ Knowledge, Skills and Self-Efficacy in AAC: A Scoping Review. Augment. Altern. Commun. 2024, 41, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegler, H.; Pless, M.; Blom Johansson, M.; Sonnander, K. Caregivers’, Teachers’, and Assistants’ Use and Learning of Partner Strategies in Communication Using High-Tech Speech-Generating Devices with Children with Severe Cerebral Palsy. Assist. Technol. 2021, 33, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, H.; Hanigan, T.; Lovatt, F. Supporting Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) in Classrooms: Sustainable Supports within the Education Context. J. Clin. Pract. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2024, 26, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, S.; Metzger, E. Barriers to Learning for Sustainability: A Teacher Perspective. Sustain. Earth Rev. 2023, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeremy, J.; Spandagou, I.; Hinitt, J. Teacher–Therapist Collaboration in Inclusive Primary Schools: A Scoping Review. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2024, 71, 593–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R.; Schimke, E.; Mathew, A.; Scarinci, N. Interprofessional Practice between Speech-Language Pathologists and Classroom Teachers: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 2023, 54, 1358–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potvin, A.S.; Boardman, A.G.; Scornavacco, K. Professionalizing Teachers through a Co-Design Learning Framework. Teach. Dev. 2023, 27, 630–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, A.M.; Doyle, C.; Gaffy, E.; Batchelor, F.; Polacsek, M.; Savvas, S.; Dow, B. Co-Designing a Dementia-Specific Education and Training Program for Home Care Workers: The ‘Promoting Independence through Quality Dementia Care at Home’ Project. Dementia 2022, 21, 899–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanley, E.; Dalton, C.; Lehane, E.; Martin, A.-M. Communication Partners’ Perceptions of Their Roles and Responsibilities in the Design, Planning and Use of Augmentative and Alternative Communication with Individuals with Severe or Profound Intellectual Disability: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 2025, 53, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, Y.; McCleary, M.; Smith, M. Instructional Strategies Used in AAC Direct Interventions with Children to Support Graphic Symbol Learning: A Systematic Review. Child Lang. Teach. Ther. 2018, 34, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer Anwar, R.; Hart Barnett, J.E. AAC in AACtion: Collaborative Strategies for Special Education Teachers and Speech-Language Pathologists. Interv. Sch. Clin. 2024, 60, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education. Education White Paper 6: Special Needs Education: Building an Inclusive Education and Training System. Available online: https://www.vvob.org/files/publicaties/rsa_education_white_paper_6.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Department of Basic Education. Policy on Screening, Identification, Assessment and Support (SIAS); Department of Basic Education, Sol Plaatje House: Pretoria, South Africa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tönsing, K.M.; Soto, G. Multilingualism and Augmentative and Alternative Communication: Examining Language Ideology and Resulting Practices. Augment. Altern. Commun. 2020, 36, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simasiku, L. The Impact of Code Switching on Learners’ Participation during Classroom Practice. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2016, 4, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock-Utne, B. Language-in-Education Policies and Practices in Africa with a Special Focus on Tanzania and South Africa. In Third International Handbook of Globalisation, Education and Policy Research; Zajda, J., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 609–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PEO Approach | Criteria | Rationale | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population (P) | School-aged learners (children from the age of five to the age of 17) | A child must be at least five years old or become six in June of the year they enter grade 1 [24]. | Learners between the ages of 5 and 17 years. | Children younger than five years or older than 17 years were excluded from the review. |

| Learners with diverse educational needs who are candidates for AAC | The World Health Organization (WHO) states that disability can be experienced in three dimensions: a person’s body structure and function, including anatomical and physiological impairments and mental functioning [25]. Anatomical and physiological impairments refer to a learner’s health condition [25]. | Learners with diverse educational needs include learners with heterogeneous health conditions. The following are health conditions that contribute to communication difficulties for learners: Physical impairments: including cerebral palsy (CP), neuromuscular diseases, etc. Sensory impairments: Vision and hearing impairments, including sensory integration difficulties. Neurodiversity: autism spectrum disorder; Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD); and intellectual, behavioural, and learning impairments (dyslexia). | Learners without disabilities were excluded. | |

| Mainstream schools or special schools | No schools are excluded, as learners with diverse educational needs are also situated in both mainstream and special schools. | Both public and private mainstream and special schools were included. | No schools were excluded. | |

| Exposure (E) | Types of AAC strategies/systems used in the classroom | Both unaided and aided AAC support the social–academic inclusion of learners with diverse educational needs [20]. | Unaided AAC includes eye movement, facial expressions, vocalizations, body movements, gestures, and signs. Aided AAC, consisting of strategies including non-speech-generated technology (e.g., picture boards, Pragmatic Organization Dynamic Display books, etc.), and speech-generating technology (e.g., Go Talk, phone, or iPad with software), will be included. | Studies that focused on oral communication or sign language only were excluded. This is because spoken and sign language are linguistic systems that can be utilized independently from AAC and are rule-based systems [6]. |

| Outcome (O) | Success of the performance | Classroom instruction strategies: Teaching strategies used by communication partners in the classroom. Learning process: Activity or opportunity through which learners and teachers acquire new knowledge, skills, or attitudes. Participant proficiency: Capacity building in learners. | Studies were included if they focused on AAC strategies used in school-related activities and teacher reports on AAC strategies used in school-related activities. | Studies on symbol design, vocabulary selection for AAC systems, and teachers’ and professionals’ attitudes or perceptions of AAC were excluded. |

| Demographics | Reported Strategies | Maintenance Factors | Outcomes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference and Country | Aim | Study Design | Population | |||

| Alant and Moolman [33] (South Africa) | To investigate the learning of Blissymbols by preschoolers with Down syndrome. | Quantitative small-group design | Participants: Preschoolers with Down syndrome (n = 4; 4.7–7 years old) Language: Afrikaans (n = 4) Context: Special schoolPreschool Communication partner: Teacher | AAC strategy/system Aided AAC:

|

|

|

| Alant et al. [34] (South Africa) | To investigate whether the degree of translucency rated by children with autism spectrum disorder changed as a result of repeated exposures to Blissymbols. | Quantitative within-subject design | Participants: Learners with autism spectrum disorder (n = 22; 6–8 years old) Languages: Afrikaans (n = 10) English (n = 5) African languages (n = 7) Context: Special school Communication partner: Researcher (SLT); Teacher | AAC strategy/system: Aided AAC:

Unaided AAC:

|

|

|

| Bornman and Alant [35] (South Africa) | To establish the prevalence of non-speaking children enrolled in schools for children with severe mental disabilities in the greater Pretoria metropolitan substructure by compiling a profile regarding their functioning in different skill areas (cognitive, motor, sensory, communication, and social). | Quantitative survey | Participants: 412 children with a severe intellectual disability (n = 412; 3–12 years old) Language: Not specified Context: Special schools Communication partner: Teachers | AAC strategy/system: Aided AAC:

|

|

|

| Dada et al. [36] (South Africa) | To explore the niche concept and its application in explaining the variation between individuals in activity-based interventions. | Quantitative, single-subject, multiple-probe design with four participants | Participants: Children with cerebral palsy (n = 3) and Down syndrome (n = 1); between 8.1 and 12.1 years old. Language: Not specified Context: Special school Communication partner: Researcher | AAC strategy/system: Aided AAC:

|

|

|

| Dada et al. [37] (South Africa) | (a) To examine the frequency with which the PCS were selected as target symbols and non-target PCS. (b) To explore the factors that might contribute to errors. (c) To determine the correlation between the participants’ scores on English vocabulary measures and their accuracy in selecting target PCS. | Quantitative non-experimental descriptive design | Participants: Children with a mild intellectual disability (n = 30; 12–15 years old) Language: isiZulu (n = 22) Sepedi (n = 3) Setswana (n = 3) Sesotho (n = 1) isiXhosa (n = 1) Context: Special school Communication partner: Researcher (SLT) | AAC strategy/system: Aided AAC:

|

|

|

| Geiger [38] (Botswana) | To describe the first cycle of an ongoing, long-term action research study, which focuses on valuable resources within several southern African cultures in order to foster inclusive environments where children with little or no functional speech can participate communicatively. | Quantitative case study | Participants: Child with CP (n = 1; seven years) Language: Setswana Context: Residential rehabilitation center that provides classroom instruction programs Communication partner: Teacher Researcher (SLT) Grandmother | AAC strategy/system: Aided AAC:

|

|

|

| Heslop and Mophosho [39] (South Africa) | To expand our understanding of the communication strategies used by teachers of pre-schoolers with autism spectrum disorder in Johannesburg, South Africa. | Qualitative descriptive interviews | Participants: Teachers (n = 5) Languages: Not specified Context: Special schoolPreschool Communication partner Children with autism spectrum disorder between the ages of 3–5.11 years | AAC strategy/system: Aided AAC:

|

|

|

| Johnson et al. [40] (South Africa) | To identify how professionals identify pain in children with cerebral palsy and how these children communicate their pain. | Qualitative descriptive focus groups | Participants: Teachers (n = 38) Languages: Not specified Context: Special school Communication partner: Children with CP | AAC strategy/system: Aided AAC:

|

|

|

| Laher and Dada [41] (South Africa) | To determine and compare the acquisition of receptive vocabulary items during implementation of aided language stimulation with dosages of 40% and 70%, respectively. | Quantitative adapted alternating treatment design | Participants: Children with a severe intellectual disability (n = 6; 8–13 years) Languages: Not specified Context: Special school Communication partner: Researcher (SLT) | AAC strategy/system: Aided AAC:

|

|

|

| Lilienfield and Alant [42] (South Africa) | To determine the effect of a peer-training program on the interaction patterns of an adolescent who used AAC. | Quantitative descriptive single-case study; observational data collection via video; and pre- and post-intervention measures | Participant: A child with CP (n = 1; 15 years and 2 months) Languages: Not specified Context: Special school Communication partner: Peers | AAC strategy/system: Aided AAC:

|

|

|

| McDowell and Bornman [43] (South Africa) | To determine the perceptions of special education teachers in South Africa regarding using KWS. | Quantitative descriptive paper-based survey | Participants: Teachers (n = 101) Language: Not specified Context: Special schools Communication partner: Children with CCN | AAC strategy/system: Aided AAC:

Unaided AAC:

|

|

|

| Naudé et al. [44] (South Africa) | To describe the effect of an augmented-input intervention in facilitating change, combine, and compare subtraction word problems in children with intellectual disabilities. | Quantitative multiple baseline experimental design across behaviors | Participants: Children with an intellectual disability (n = 7; 8–12.11 years) Languages: English Context: Special school Communication partner: Researchers (SLT and audiologist) | AAC strategy/system: Aided AAC:

|

|

|

| Tönsing and Dada [5] (South Africa) | To understand the barriers and facilitators in supporting students using aided AAC for expression, this study aimed to assess the provision and implementation of communication boards in classrooms in special schools across six districts in a metropolitan area in South Africa, and to explore teachers’ perceptions of factors influencing AAC implementation. | Concurrent mixed methods | Participants: Teachers (n = 27) Languages: Not specified Context: Special schools (preschool and foundation phase (grade 1–3)) Communication partner: Children with CCN | AAC strategy/system: Aided AAC:

|

|

|

| Tönsing et al. [45] (South Africa) | To determine if an intervention strategy targeting two-symbol combinations, which uses a hierarchy of prompts during shared story reading, can facilitate the production of both target and non-target graphic symbol combinations in response to picture stimuli (not used in the story) by children with limited speech. | Quantitative single-subject multiple-probe design across three types of semantic relations | Participants: Children with CCN (n = 4; 6.5–10.8 years) Languages: English Context: Special school Communication partner: Researcher (SLT) | AAC strategy/system: Aided AAC:

|

|

|

| Travis and Geiger [46] (South Africa) | To determine the effect of PECS on the frequency of requesting and commenting behavior and length of verbal utterances in two children with autism spectrum disorder. | Mixed research design: quantitative (single-subject multiple-baseline design) and qualitative components | Participants: Children with autism spectrum disorder (n = 2; 9.6–9.10) Language: English Context: Special school Communication partners: Teachers and class assistants | AAC strategy/system: Aided AAC:

|

|

|

| Uys and Harty [47] (South Africa) | To increase teachers’ knowledge and skill regarding the use of aided language stimulation in inclusive classrooms. | Quantitative two-phase training program including pre-test and post-test designs | Participants: Teachers (n = 78); 2 SLTs (n = 2) Language: Afrikaans English Setswana Context: Mainstream school and preschool (inclusive classroom) Communication partner: Children with CCN and typical learners | AAC strategy/system: Aided AAC:

|

|

|

| Van der Bijl et al. [48] (South Africa) | To compare two strategies of sight word instruction in children with moderate to severe mental disability. | Quantitative pre-test–post-test comparison group design with a withdrawal period | Participants: Children with intellectual disability (n = 33) Languages: Afrikaans Context: Special school Communication partner: Teacher | AAC strategy/system: Aided AAC:

|

|

|

| Van Niekerk and Tönsing [49] (South Africa) | To provide a broad perspective on factors that facilitate communication and participation in preliterate children using electronic AAC systems accessed through eye gaze. | Qualitative case study | Participants: Children with CP (n = 2; 7 and 9 years) Language: Afrikaans English Context: Special school Communication partners: Parents and teachers | AAC strategy/system: Aided AAC:

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuyler, A.; Ledwaba, G.R.; Clasquin-Johnson, M.G.; Motitswe, J.M.C.; Gouws, E.; Mashau, T.I.; Chauke, M.; Johnson, E. Augmentative and Alternative Communication Strategies for Learners with Diverse Educational Needs in African Schools: A Qualitative Literature Review. Disabilities 2025, 5, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5020059

Kuyler A, Ledwaba GR, Clasquin-Johnson MG, Motitswe JMC, Gouws E, Mashau TI, Chauke M, Johnson E. Augmentative and Alternative Communication Strategies for Learners with Diverse Educational Needs in African Schools: A Qualitative Literature Review. Disabilities. 2025; 5(2):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5020059

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuyler, Ariné, Gloria R. Ledwaba, Mary G. Clasquin-Johnson, Jacomina M. C. Motitswe, Emile Gouws, Tshifhiwa I. Mashau, Margaret Chauke, and Ensa Johnson. 2025. "Augmentative and Alternative Communication Strategies for Learners with Diverse Educational Needs in African Schools: A Qualitative Literature Review" Disabilities 5, no. 2: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5020059

APA StyleKuyler, A., Ledwaba, G. R., Clasquin-Johnson, M. G., Motitswe, J. M. C., Gouws, E., Mashau, T. I., Chauke, M., & Johnson, E. (2025). Augmentative and Alternative Communication Strategies for Learners with Diverse Educational Needs in African Schools: A Qualitative Literature Review. Disabilities, 5(2), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5020059