Strategies for Increasing Accessibility and Equity in Health and Human Service Educational Programs: Protocol for a National, Mixed Methods Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview

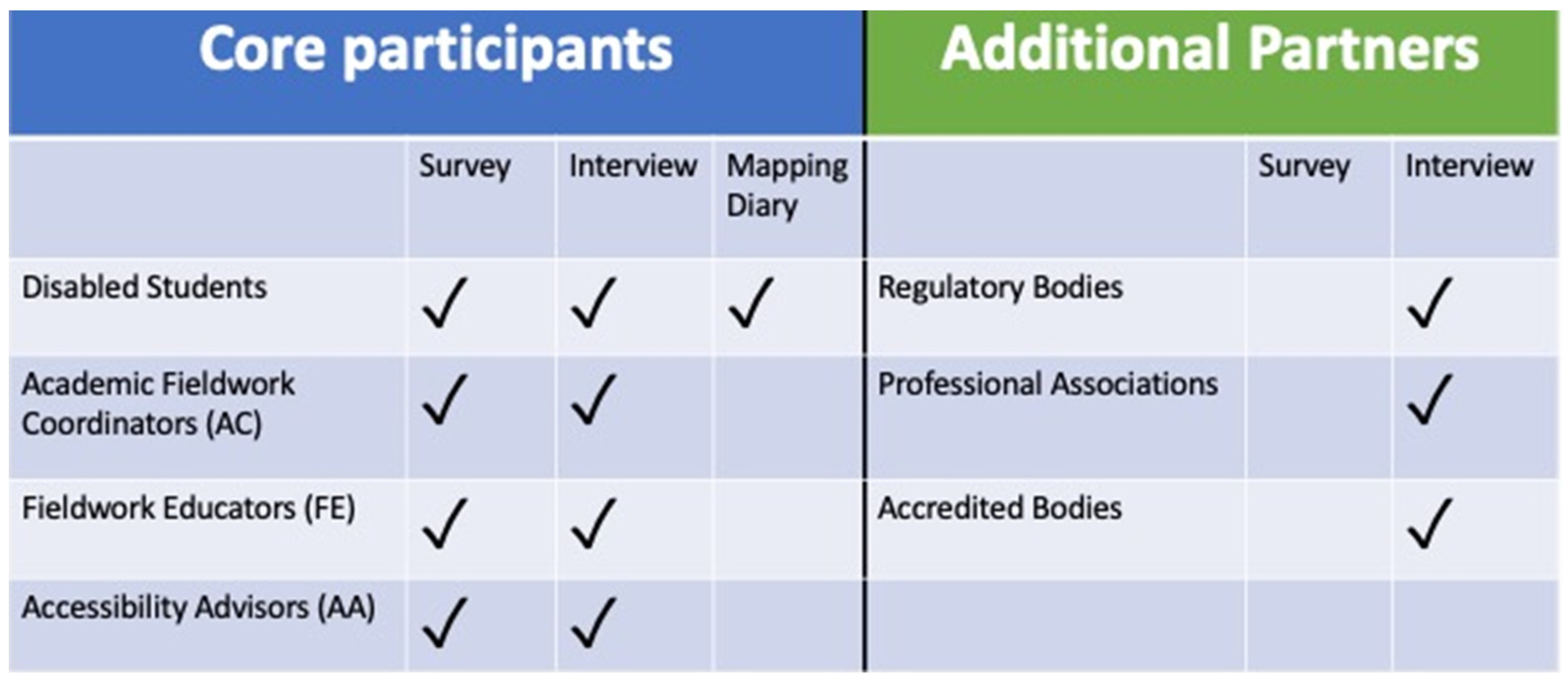

2.2. Participants and Eligibility Criteria

2.2.1. Core Participants

- o

- Disabled learners: Current learners or up to a year after completion of the program who self-identify as living with disability and/or learners requiring accommodations in fieldwork.

- o

- Academic Fieldwork Coordinators (ACs): The person at a university program who oversees fieldwork aspects of the curriculum and finds suitable fieldwork sites for learners in their program to attend. They are often university faculty members. AC is the term we use to cover a broad range of related (or alternate) terminology such as fieldwork coordinator, field coordinator, field education coordinator, academic fieldwork coordinator, program coordinator for practicum and academic coordinator of clinical education.

- o

- Fieldwork Educators (FEs): The person at a fieldwork site who is a practicing HHS professional who supervises learners during fieldwork. FE is the term we use to cover a broad range of related (or alternate) terminology such as preceptor, supervisor, field placement supervisor, practicum supervisor, professional practice educator, faculty advisor and clinical instructor.

- o

- University Accessibility Advisors (AAs): Accessibility Advisors are employed by universities to support learners seeking and receiving accommodations. They are legally required to recommend and confirm accommodations for learners that require them.

2.2.2. Eligibility

- To be eligible to participate, ACs, FEs and AAs need to be in their respective roles for at least six months.

2.2.3. Professional Partners

- o

- Regulatory bodies or colleges: These are typically provincial bodies that regulate their respective professions with a mandate to serve the public. They are responsible for overseeing the professional standards, requirements and conditions for licensing. Examples of potential participants will include the Registrar, Chief Executive Officer, Deputy registrar, Managers or chairs of committees.

- o

- Professional Associations: both provincial and national associations representing practitioners from their respective professions. They represent and work on behalf of their members and profession. Examples of potential participants will include the Chief Executive Officer, Chief professional practice department, membership department officer or chairs of committees.

- o

- Accreditation Bodies: These bodies accredit or approve university programs for their respective professions. Accreditation is mostly done by professional associations. Examples of potential participants will include the Commissioners of the accreditation body, or chairs of committees.

2.3. Tools and Measures for Data Collection

2.3.1. Online Surveys

2.3.2. Semi Structured Interviews

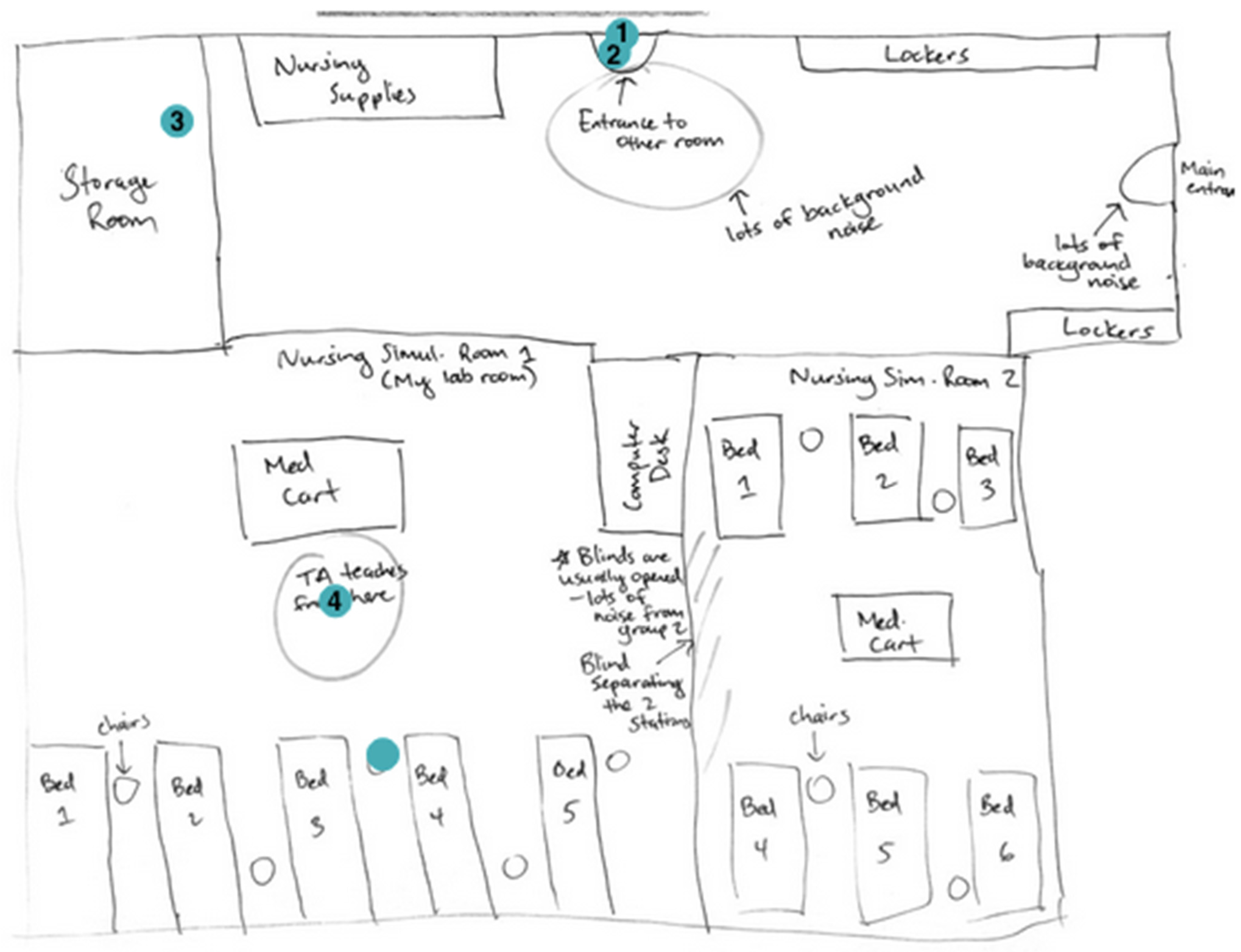

2.3.3. Online Mapping Diary

2.4. Procedure

2.4.1. Recruitment and Consent

Core Participants

- Survey Recruitment

- o

- Learner recruitment: Learners receive the study invite via email from their respective ACs. Student Associations (national groups and associations within universities) and student Facebook groups are also sent invites with a link to the learner survey.

- o

- AC recruitment: Emails with invite letters and consent form attachments are sent out to relevant programs and departments in 61 Canadian universities to forward to their ACs. ACs with publicly available email addresses posted on university websites are also directly emailed. The invite also include the learner and FE invites and ACs are asked to forward them on to relevant individuals and cohorts.

- o

- FE recruitment: FEs receive the study invite via email from the university program for which they supervise learners. Additionally, all regulatory bodies and national associations of participating professions are asked to distribute the study invite to their memberships, and to advertise on their social media platforms (Facebook and Twitter), e-bulletins and newsletters. Finally, we send direct study invites via email to FE listings provided by a few professional associations where members had given permission to be contacted for research purposes. The invites included a link to the FE survey.

- o

- AA recruitment: Accessibility offices in 16 Canadian universities that offer at least three of the 10 targeted HHS professions and had publicly available email addresses posted on their university websites, are emailed the study invite and consent form. Additionally, all members sent the study invite and consent forms to the accessibility offices in their respective universities (N = 10). The invites include a link to the AA survey. Altogether, 26 universities are approached.

- o

- Consent: In addition to attaching the consent forms to all invites, the consent form is also linked at the start of the survey and participants have the opportunity to download it if they wish. Finally, at the end of the survey participants are informed that by submitting the survey they consent to participate in this portion of the study.

- Post-Survey Interview and Online Mapping Diary Recruitment

Professional Partners Recruitment

2.4.2. Honoraria

2.5. Data Analysis

2.5.1. Quantitative Data Analysis

- o

- Comparing AC, FE and AA participants who identify as having a disability and those who do not have a disability: nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test will be for non-normally distributed dependent variables. Parametric t-test will be used for normally distributed dependent variables.

- o

- Comparing professional programs: nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA test will be for non-normally distributed dependent variables. One way Analysis of Variance will be used for normally distributed dependent variables.

- o

- Comparing between men and women: nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test will be for non-normally distributed dependent variables. Parametric t-test will be used for normally distributed dependent variables.

- o

- For dichotomous dependent variables (e.g., Awareness of existing procedures regarding fieldwork accommodations) we will run cross tabulation and chi square.

- o

- For Likert scale dependent variables (e.g., perceived usefulness of FW accommodations), we will use Kruskal–Wallis one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) test for non-normally distributed dependent variables, and One way ANOVA for normally distributed dependent variables.

- o

- For repeated measures dependent variables, (e.g., Perceptions about the ability of disabled learners to attain five different core competencies and skills), for non-normally distributed dependent variables we will conduct a nonparametric test that allows control for individual variability in responses called the Friedman test. A post-hoc analysis would then be conducted using the Nemenyi test to see if any significant differences between the different types of competencies were identified from the Friedman test above. For normally distributed data we will use Multiple ANOVA with repeated measures.

2.5.2. Qualitative Data Analysis

Composite Narratives

2.5.3. The Online Mapping Diary Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meeks, L.M.; Herzer, K.R. Prevalence of Self-Disclosed Disability Among Medical Learners in U.S. Allopathic Medical Schools. JAMA 2016, 316, 2271–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brault, M.W. Americans with Disabilities: 2010. The United States Census Bureau 2012. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2012/demo/p70-131.html (accessed on 5 October 2018).

- Eickmeyer, S.M.; Do, K.D.; Kirschner, K.L.; Curry, R.H. North American medical schools’ experience and approaches to the needs of learners with physical and sensory disabilities. Acad. Med. 2012, 87, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreland, C.J.; Meeks, L.M.; Nahid, M.; Panzer, K.; Fancher, T.L. Exploring accommodations along the education to employment pathway for deaf and hard of hearing healthcare professionals. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, S.; Fuentes, K.; Ragunathan, S.; Lamaj, L.; Dyson, J. Ableism within health care professions: A systematic review of the experiences and impact of discrimination against health care providers with disabilities. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 45, 2715–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iezzoni, L.I. Why increasing numbers of physicians with disability could improve care for patients with disability. AMA J. Ethics 2016, 18, 1041–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, R.C.; Warr, R.S.; Zhao, J. Do pro-diversity policies improve corporate innovation? Financ. Manag. 2018, 47, 617–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, S.K.; Horwitz, I.B. The effects of team diversity on team outcomes: A meta-analytic review of team demography. J. Manag. 2017, 33, 987–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezsö, C.L.; Ross, D.G. Does female representation in top management improve firm performance? A panel data investigation. Strat. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 1072–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, V.; Layton, D.; Prince, S. Diversity Matters; McKinsey & Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Human Resources and Skills Development Canada. Employment. In 2010 Federal Disability Report: The Government of Canada’s Annual Report on Disability Issues; Human Resources and Skills Development Canada: Gatineau, QC, Canada, 2010; Chapter 4; pp. 39–53. [Google Scholar]

- Association of American Medical Colleges. AAMC Amicus Curiae Brief in Fisher v. University of Texas; Association of American Medical Colleges: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Beagan, B.L.; Chacala, A. Culture and diversity among occupational therapists in Ireland: When the occupational therapist is the “diverse” one. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2012, 75, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OHRC. Guidelines on Accessible Education. 2004. Available online: http://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/resources/Guides/AccessibleEducation/pdf (accessed on 5 October 2018).

- College of Nurses of Ontario. Requisite Skills and Abilities for nursing practice in Ontario. 2012. Available online: https://www.cno.org/globalassets/docs/reg/41078-skillabilities-4pager-final.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2023).

- College of Nurses of Ontario. Nursing Education Program Approval Guide. 2019. Available online: https://www.cno.org/globalassets/3-becomeanurse/educators/nursing-education-program-approval-guide-vfinal2.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2023).

- Shrewsbury, D.; Mogensen, L.; Hu, W. Problematizing medical students with disabilities: A critical policy analysis. Med. Educ. 2018, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clouder, L.; Adefila, A.; Jackson, C.; Opie, J.; Odedra, S. The discourse of disability in higher education: Insights from a health and social care perspective. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 79, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delisa, J. Physicians with disabilities: Why aren’t there more of them? N. J. Med. Sch. Pulse 2006, 4, 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, J.; Dearnley, C.; Walker, S.; Walker, L. The preparation and practice of disabled health care practitioners: Exploring the issues. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2014, 51, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, B.; Baptiste, S.; Dhillon, S.; Kravchenko, T.; Stewart, D.; Vanderkaay, S. The Experience of student occupational therapists with disabilities in Canadian universities. Int. J. High. Educ. 2014, 3, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, M.M.; Smith, S.; Barnett, S.; Pearson, T.A. What are the benefits of training deaf and hard-of-hearing doctors? Acad. Med. 2013, 88, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, S.; Dieppe, P.; Chambers, R.; MacDonald, R. Equality for people with disabilities in medicine. BMJ 2003, 327, 882–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal-Boylan, L.; Guillett, S.E. Work experiences of RNs with physical disabilities. Rehabil. Nur. 2008, 33, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal-Boylan, L. End the Disability Debate in Nursing: Quality Care is Fact. Insight into Diversity. Available online: www.insightintodiversity.com (accessed on 1 May 2013).

- Oulette, A. Patients to peers: Barriers and opportunities for doctors with disabilities. Nev. Law J. 2013, 13, 645–667. [Google Scholar]

- Bulk, L.Y.; Easterbrook, A.; Roberts, E.; Groening, M.; Murphy, S.; Lee, M.; Ghanouni, P.; Gagnon, J.; Jarus, T. We are not anything alike”: Marginalization of health professionals with disabilities. Disabil. Soc. 2017, 32, 615–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterbrook, A.; Bulk, L.; Ghanouni, P.; Lee, M.; Opini, B.; Roberts, E.; Parhar, G.; Jarus, T. The legitimization process of learners with disabilities in health and human service educational programs in Canada. Disabil. Soc. 2015, 30, 1505–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterbrook, A.; Bulk, L.Y.; Jarus, T.; Hahn, B.; Ghanouni, P.; Lee, M.; Groening, M.; Opini, B.; Parhar, G. University gatekeepers’ use of the rhetoric of citizenship to relegate the status of learners with disabilities in Canada. Disabil. Soc. 2019, 34, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarus, T.; Krupa, T.; Mayer, Y.; Battalova, A.; Bulk, L.Y.; Lee, M.; Nimmon, L.; Robert, E. Negotiating Legitimacy and Belonging: Disabled learners’ and Practitioners’ experience. Med. Educ. 2023, 57, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulk, L.Y.; Tikhonova, J.; Gagnon, J.M.; Battalova, A.; Mayer, Y.; Krupa, T.; Lee, M.; Nimmon, L.; Jarus, T. Disabled healthcare professionals’ diverse, embodied, and socially embedded experiences. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2020, 25, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, K.; James, C.; Mackenzie, L. The practice placement education experience: An Australian pilot study exploring the perspectives of health professional learners with a disability. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2006, 69, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, I.; Khanlou, N.; Ermel, R.E.; Sherk, M.; Simmonds, K.K.; Balaquiao, L.; Chang, K.Y. Students who identify with a disability and instructors’ experiences in nursing practice: A scoping review. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 19, 91–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langørgen, E.; Kermit, P.; Magnus, E. Gatekeeping in professional higher education in Norway; ambivalence among academic staff and placement supervisors towards learners with disabilities. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 24, 616–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartman, I.; Touchie, C.; Condon, K. Testing Accommodations: Environmental Scan Report; Medical Council of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tee, S.; Cowen, M. Supporting learners with disabilities—Promoting understanding amongst mentors in practice. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2012, 12, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, E.; Jarus, T.; Mayer, Y.; Zaman, S.; Mira, F.M.; Boniface, J.; Boucher, M.; Bulk, L.Y.; Chen, S.; Drynan, D.; et al. Professional placement as a unique challenge for learners with disabilities in health and human service educational programs. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabel, S.L.; Miskovic, M. Discourse and the containment of disability in higher education: An institutional analysis. Disabil. Soc. 2014, 29, 1145–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennals, P.; Fossey, E.; Howie, L. Postsecondary Study and Mental Ill-Health: A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Research Exploring Students’ Lived Experiences. J. Ment. Health 2015, 24, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolmage, J.T. Academic Ableism—Disability and Higher Education; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, N.R. Political disclosure: Resisting ableism in medical education. Disabil. Soc. 2019, 35, 389–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burghardt, M.; Edelist, T.; Schormans, A.F.; Yoshida, K. Coming to Critical Disability Studies: Critical Reflections on Disability in Health and Social Work Professions. Can. J. Disabil. Stud. 2021, 10, 23–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodley, D. Dis/entangling critical disability studies. Disabil. Soc. 2013, 28, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shildrick, M. Critical disability studies: Rethinking the conventions for the age of postmodernity. In Routledge Handbook of Disability Studies; Watson, N., Roulstone, A., Thomas, C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 30–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gieseking, J.J. Where We Go From Here: The Mental Sketch Mapping Method and Its Analytic Components. Qual. Inq. 2013, 19, 712–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamraie, A. Mapping Access: Digital Humanities, Disability Justice, and Sociospatial Practice. Am. Q. 2018, 70, 455–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickell, K. ‘Mapping’ and ‘doing’ critical geographies of home. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2012, 36, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, L.; Mullarkey, S.; Reavey, P. Building visual worlds: Using maps in qualitative psychological research on affect and emotion. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2020, 17, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinreb, A.R.; Rofè, Y. Mapping feeling: An approach to the study of emotional response to the built environment and landscape. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2013, 30, 127–145. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, K. Making Sense of Place: Mapping as a Multisensory Research Method. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, R. The use of composite narratives to present interview findings. Qual. Res. 2019, 19, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauwels, L.; Mannay, D. The SAGE Handbook of Visual Research Methods, 2nd ed.; Pauwels, L., Mannay, D., Eds.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Profession | Aud 1 | SLP 2 | DH 3 | Den 4 | MD 5 | Nur 6 | OT 7 | PT 8 | Psych 9 | SW 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province | |||||||||||

| BC | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 6 | |

| Alberta | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | |

| Saskatchewan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| Manitoba | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| Ontario | 2 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 16 | 5 | 5 | 11 | 15 | |

| Québec | 1 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 5 | |

| New Brunswick | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| NL | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Nova Scotia | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| PEI | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total numbers per Profession | 5 | 12 | 4 | 10 | 17 | 47 | 14 | 15 | 32 | 36 | |

| Learner Survey | FE Survey | AC Survey | AA Survey | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Capacity | ||||

| (a) Recent trends in the numbers of learners requesting accommodations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| (b) Fieldwork staff and support at the university | ✓ | |||

| 2. Procedures | ||||

| (a) Awareness and perceptions of existing procedures regarding fieldwork | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| (b) Time spent on communications regarding accommodations before, during and after fieldwork | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| (c) Practices and preferences regarding time spent planning for least and most complex fieldwork accommodations | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| (d) Current practices, preferences and satisfaction regarding the involvement of other professional partners in the fieldwork accommodation process | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 3. Accommodations | ||||

| (a) Types and/or number of fieldwork accommodations received/provided/ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| requested—and the perceived usefulness of those accommodations | ||||

| 4. Accountability/preparedness | ||||

| (a) Evaluation of the effectiveness of fieldwork accommodations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| (b) Confidence and satisfaction with one’s own experiences with accommodations in fieldwork and academic settings | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| (c) AAs’ knowledge of fieldwork sites and supporting learners living with disabilities | ✓ | |||

| (d) Awareness, preferences and/or perceived usefulness of available training, education or resources regarding fieldwork accommodations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 5. Perceptions and attitudes | ||||

| (a) Evaluation of the effectiveness of fieldwork accommodations | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| (b) Confidence and satisfaction with one’s own experiences with accommodations in fieldwork and academic settings | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 6. Impacts of current broken systems | ||||

| (a) Disabled learners’ confidentiality, emotional energy spent and costs and burdens experienced in relation to accommodations in fieldwork and academic settings | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| (b) Contexts surrounding potential or actual fieldwork breakdown/fails | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| (c) Delayed fieldwork accommodation requests and consequences | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 7. Demographic information | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jarus, T.; Stephens, L.; Edelist, T.; Katzman, E.; Holmes, C.; Kamenetsky, S.; Epstein, I.; Zaman, S. Strategies for Increasing Accessibility and Equity in Health and Human Service Educational Programs: Protocol for a National, Mixed Methods Study. Disabilities 2024, 4, 444-458. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4030028

Jarus T, Stephens L, Edelist T, Katzman E, Holmes C, Kamenetsky S, Epstein I, Zaman S. Strategies for Increasing Accessibility and Equity in Health and Human Service Educational Programs: Protocol for a National, Mixed Methods Study. Disabilities. 2024; 4(3):444-458. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4030028

Chicago/Turabian StyleJarus, Tal, Lindsay Stephens, Tracey Edelist, Erika Katzman, Cheryl Holmes, Stuart Kamenetsky, Iris Epstein, and Shahbano Zaman. 2024. "Strategies for Increasing Accessibility and Equity in Health and Human Service Educational Programs: Protocol for a National, Mixed Methods Study" Disabilities 4, no. 3: 444-458. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4030028

APA StyleJarus, T., Stephens, L., Edelist, T., Katzman, E., Holmes, C., Kamenetsky, S., Epstein, I., & Zaman, S. (2024). Strategies for Increasing Accessibility and Equity in Health and Human Service Educational Programs: Protocol for a National, Mixed Methods Study. Disabilities, 4(3), 444-458. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4030028