The Importance of Collaboration in Pediatric Rehabilitation for the Construction of Participation: The Views of Parents and Professionals

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

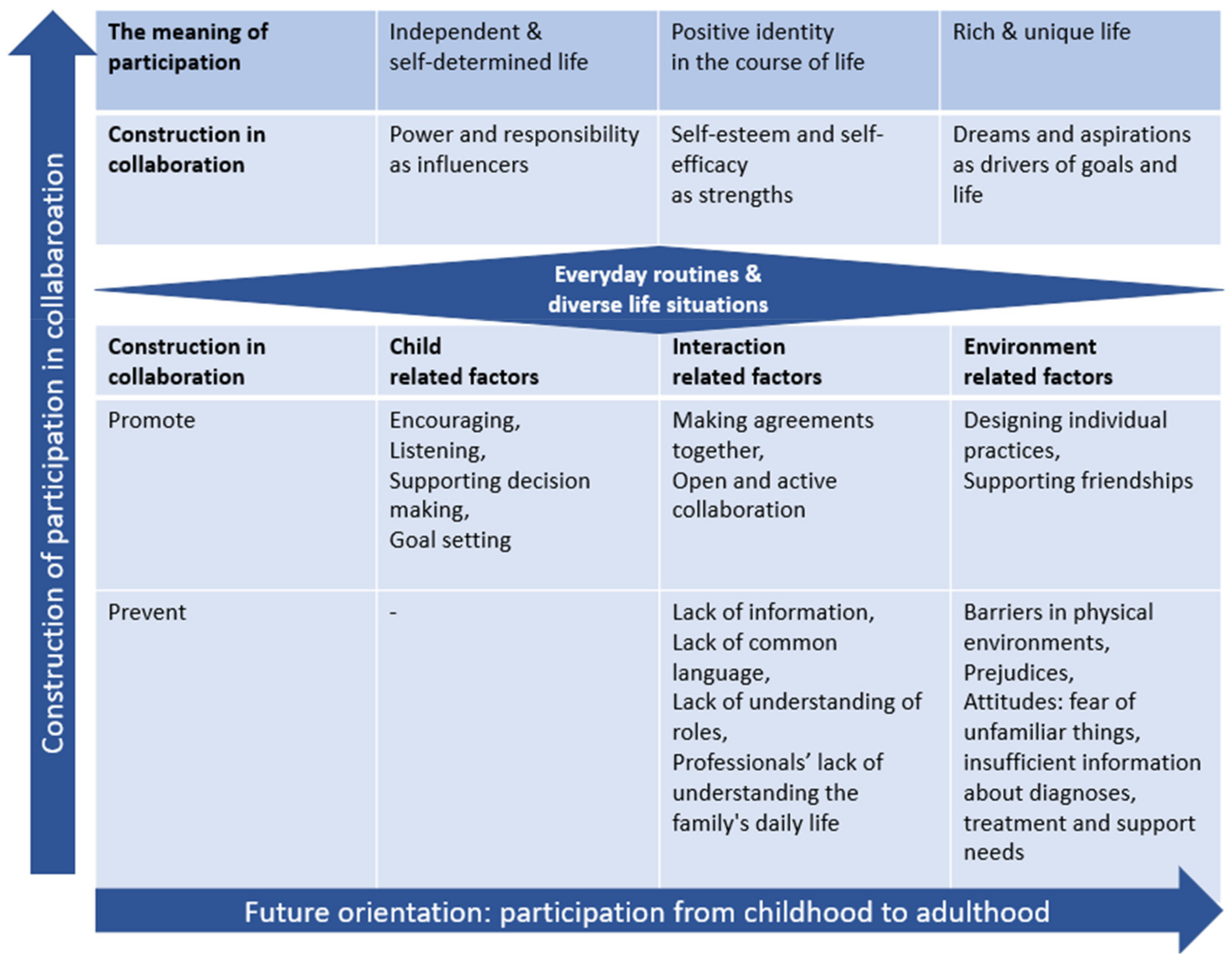

3.1. Factors Promoting the Child’s Participation in Life Situations through Adults’ Collaboration

“Adults should try to listen to children. Children’s views should be taken into account. The child can tell, if only he gets a chance.”(Teacher 1)

“I have always considered it really important to be honest with the child and to encourage the child. You are an expert in your own affairs.”(Parent 1)

“The child has to be involved in all the meetings where her issues are discussed and have an opportunity to say her own opinions, because she herself knows her own disability and needs well and tells them what is involved in her disability.”(Parent 3)

“Not so that parents do their own path, therapists and teachers their own, but parents together with others.”(Parent 5)

“Not just managing somehow in life, but to live the most diverse and rich, happy everyday life as possible.”(Parent 3)

“In both the rehabilitation and school worlds, the child should be part of the goal setting. Not just the object, but the child himself should be creating his own goals.”(Therapist 1)

“If weight training is boring in therapy for the child, then it should be considered what would be an alternative training. For example, in downhill skiing we do exactly the same thing but on skis. That child could find motivation for action. Of course, it demands a bit from all of us adults, but you don’t always have to see it through those same lenses. I feel like child’s ideas can sometimes be pretty awesome, that I’d like to try something like that.”(Therapist 1)

“Peers also give strength and alternatives to the child and adults should support friendship building.”(Teacher 2)

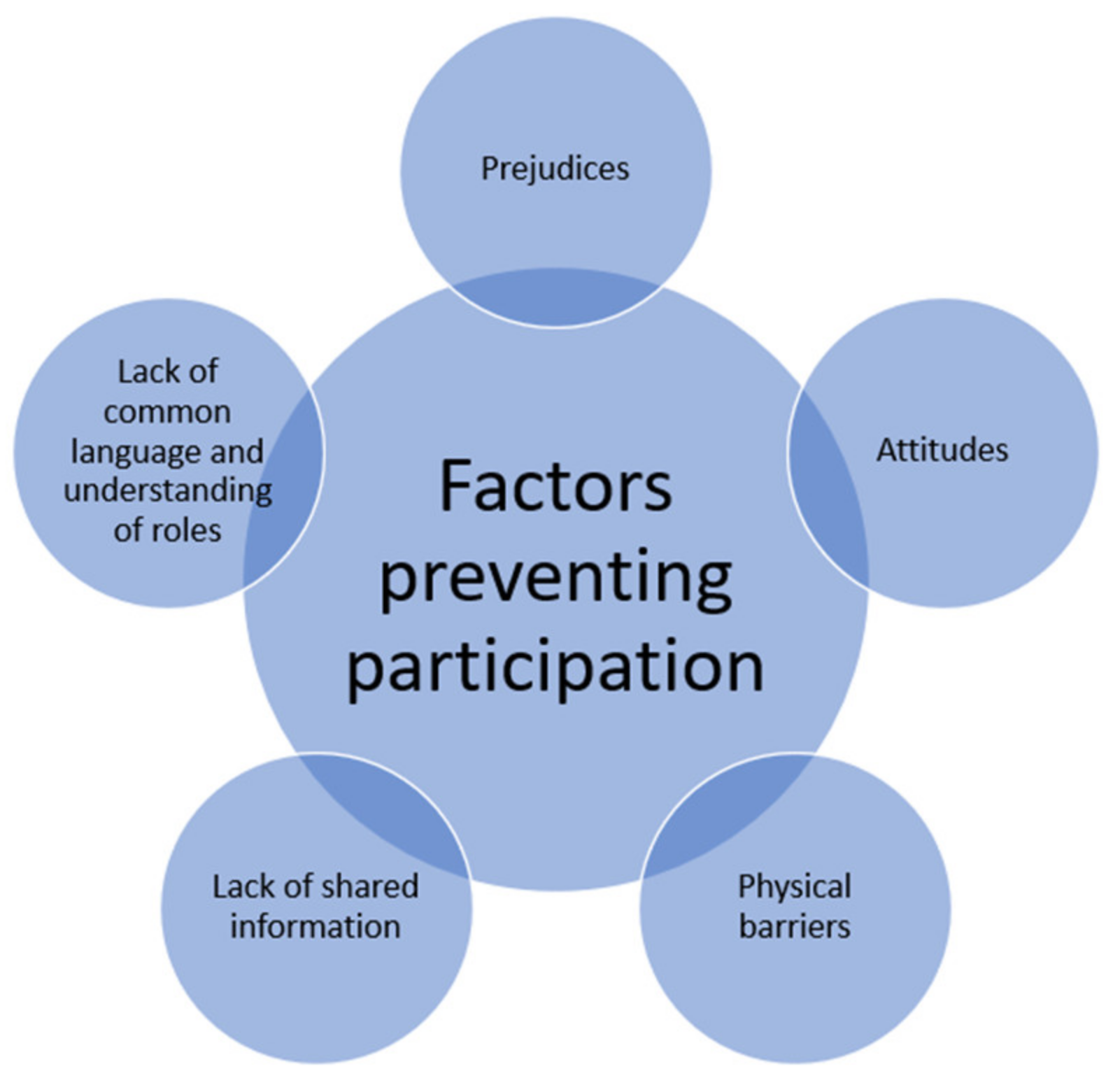

3.2. Factors Preventing the Child’s Participation in Life Situations in Adults’ Collaboration

“The one whose disability is visible is able to be directed at it and is placed in a different position. There are certainly other children out there who need special attention and special support and a different approach to getting and being able to receive the information that is passed on in class. That wheelchair does not stop a child from thinking and learning and using his head.”(Parent 5)

“Somewhere in the countryside there was a school in an old building where the toilet could only be built upstairs, so a child in a wheelchair could visit the toilet once a day only.”(Therapist 2)

“Environment has a huge affect on the child and parents. For example a clinical environment, like a hospital, may make it difficult to understand a home environment and its needs. In the home, the atmosphere is freer for the child and parents to express thoughts and ideas.”(Parent 3)

“In some situations, parents try to be more as a friend to the child, rather than be a parent. Giving too much freedom to the child, for example playing video games at anytime. That can be a problem in school or therapy sessions when the child is forbidden to do that.”(Teacher 1)

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vargus-Adams, J.N.; Majnemer, A. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) as a framework for change: Revolutionizing rehabilitation. J. Child Neurol. 2014, 29, 1030–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbaum, P.; Gorter, J. The ’F-words’ on childhood disability: I swear this is how we should think. Child Health Care Dev. 2011, 38, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dahan-Oliel, N.; Shikako-Thomas, K.; Majnemer, A. Quality of life and leisure participation in children with neurodevelopmental disabilities: A thematic analysis of the literature. Qual. Life Res. 2012, 21, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustavsson, A. About the language of Participation. In The Language of Participation; Gustavsson, A., Ed.; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 1, pp. 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Molin, M. Participation in the disability field. A conception analysis. In The Language of Participation; Gustavsson, A., Ed.; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Switzerland, 2004; Volume 1, pp. 61–80. (In Swedish) [Google Scholar]

- Imms, C.; Granlund, M.; Wilson, P.H.; Steenbergen, B.; Rosenbaum, P.L.; Gordon, A.M. Participation, both a means and an end; a conceptual analysis of processes and outcomes in childhood disability. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2016, 59, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sinclair, R. Participation in Practice: Making it Meaningful, Effective and Sustainable. Child. Soc. 2004, 18, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaby, D.; Hand, C.; Bradley, L.; DiRezze, B.; Forhan, M.; DiGiacomo, A.; Law, M. The effect of the environment on participation of children and youth with disabilities: A scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2014, 35, 1589–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vänskä, N.; Sipari, S.; Haataja, L. What is meaningful participation? Photo-elicitation interviews of children with disabilities. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2020, 40, 595–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaby, D.R.; Law, M.C.; Majnemer, A.; Feldman, D. Opening doors to participation of youth with physical disabilities: An intervention study. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2016, 83, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhardt, F.; Ullenhag, A.; Jahnsen, R.; Dolva, A.S. Perceived facilitators and barriers for participation in leisure activities in children with disabilities: Perspectives of children, parents and professionals. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2021, 28, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciver, D.; Rutherford, M.; Arakelyan, S.; Kramer, J.M.; Richmond, J.; Todorova, L. Participation of children with disabilities in school: A realist systematic review of psychosocial and environmental factors. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adair, B.; Ullenhag, A.; Keen, D. The effect of interventions aimed at improving participation outcomes for children with disabilities: A systematic review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2015, 57, 1093–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, I.; Morgan, C.; Fahey, M. State of the evidence traffic lights 2019: Systematic review of interventions for preventing and treating children with cerebral palsy. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2020, 20, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anaby, D.; Khetani, M.; Piškur, B.; van der Holst, M.; Bedell, G.; Schakel, F.; de Kloet, A.; Simeonsson, R.; Imms, C. Towards a paradigm shift in pediatric rehabilitation: Accelerating the uptake of evidence on participation into routine clinical practice. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, L. Studies of Child Perspectives in Methodology and Practice with ‘Osallisuus’ as a Finnish Approach to Children’s Reciprocal Cultural Participation. In Childhood Cultures in Transformation; Odegaard, E., Borgen, J., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, Norway, 2020; pp. 246–273. [Google Scholar]

- Isola, A.M.; Kaartinen, H.; Leemann, L.; Lääperi, R.; Schneider, T.; Valtari, S.; Keto-Tokoi, A. Mitä osallisuus on? In Osallisuuden Viitekehystä Rakentamassa; THL: Helsinki, Finland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gal, T. An ecological model of child and youth participation. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 79, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhead, M. Foreword. In A Handbook of Children and Young People’s Participation; Percy-smith, B., Thomas, N., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child; General Assembly Resolution 44/25 of 20 November 1989; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1989. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CRC.aspx (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Chiarello, L. Excellence in promoting participation: Striving for the 10Cs-client centered care, consideration on complexity, collaboration, coaching, capacity building, contextualization, creativity, community, curricular changes and curiosity. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2017, 29, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, E.; Trembley, S.; Khetani, M.; Anaby, D. The effect of child, family and environmental factors on the participation of young children with disabilities. Disabil. Health J. 2018, 11, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magill-Evans, J.; Wiart, L.; Darrah, J.; Kratochvil, M. Beginning the transition to adulthood: The experience of six families with youths with cerebral palsy. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2005, 25, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rous, B.; Meyer, C.T.; Stricklin., S.B. Strategies for supporting transitions of young children with special needs and their families. J. Early Interv. 2007, 30, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeglinsky, I.; Salminen, A.-L.; Brogren, C.E.; Autti-Rämö, I. Rehabilitation planning for children and adolescents with cerebral palsy. J. Pediatr. Rehabil. Med. 2021, 5, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grace, R.; Bowes, J. Using an ecocultural approach to explore young children’s experiences of prior-to-school care settings. Early Child Dev. Care 2011, 181, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D.W.; Shamdasi, P.N. Focus Groups: Theory and Practice, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- Palisano, R.; Rosenbaum, P.; Bartlett, D.; Livingston, M. GMFCS—Gross Motor Function Classification System; Expanded and revised; Can Child Center for Disability Research: Hamilton, ON, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, S. Focus group research. In Qualitative Research: Theory, Method, and Practice, 2nd ed.; Silverman, D., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 177–199. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, K.; Salanterä, S.; Zumstein-Shaha, M. Focus Group Interviews in Child, Youth, and Parent Research: An Integrative Literature Review. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18, 1609406919887274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millward, L. 2012 Focus groups. In Research Methods in Psychology, 2nd ed.; Breakwell, G.M., Smith, J.A., Wright, D.B., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2012; p. 616. [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S.; Kääriäinen, M.; Kanste, O.; Pölkki, T.; Utriainen, K.; Kyngäs, H. Qualitative Content Analysis: A Focus on Trustworthiness. SAGE Open 2014, 4, 2158244014522633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, G.; Alves, I.; Granlund, M. Participation and environmental aspects in education and the ICF and the ICF-CY: Findings from a systematic literature review. Dev. Neurorehabil. 2012, 15, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järvikoski, A.; Martin, M.; Autti-Rämö, I.; Härkäpää, K. Shared agency and collaboration between the family and Professionals in medical rehabilitation of children with severe disabilities. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2013, 6, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, L.; Phelan, S.; McKillop, A.; Andersen, J. Child, parent, and clinician experiences with a child-drive goal setting approach in paediatric rehabilitation. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, U.M.; Brauchle, G.; Kennedy-Behr, A. Collaborative goal setting with and for children as part of therapeutic intervention. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017, 39, 1589–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipari, S.; Vänskä, N.; Pollari, K. Lapsen Edun Toteutuminen Kuntoutuksessa. Osallistumista ja Toimijuutta Vahvistavat Hyvät Käytännöt. Sosiaali- ja Terveysturvan Raportteja 5/2017. Saatavilla Osoitteessa. 2017. Available online: https://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10138/220550 (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- King, G.; Lisa, A.; Roger Ideishi, C.; D’Arrigo, R.; Smart, E.; Ziviani, J.; Pinto, M. The Nature, Value, and Experience of Engagement in Pediatric Rehabilitation: Perspectives of Youth, Caregivers, and Service Providers. Dev. Neurorehabilit. 2020, 23, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palisano, R.J.; Chiarello, L.A.; King, G.A.; Novak, I.; Stoner, T.; Fiss, A. Participation-based therapy for children with physical disabilities. Disabil. Rehabil. 2012, 34, 1041–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vänskä, N.; Sipari, S.; Jeglinsky, I.; Lehtonen, K.; Kinnunen, A. Co-development of the CMAP Book: A tool to enhance children’s participation in pediatric rehabilitation. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participants (N = 10) | Mean Age (Range) | |

|---|---|---|

| Parents (N = 5) of three primary school children (age 8–12) | Mother (N = 3) | 42.7 (29 to 52 years) |

| Father (N = 2) | 58.0 (both were 58 years old) | |

| Professionals (N = 5) | Therapists (N = 3) (two physiotherapists and one occupational therapist) | 41.3 (35 to 49 years) |

| Teachers (N = 2) (one class teacher and one special teacher) | 28.0 (30 to 26 years) | |

| Focus Groups | Participants | Focus Group Discussion Themes |

|---|---|---|

| Interview 1. | Participants in their own groups | Participants’ perception of the child’s participation |

| Interview 2. | Participants in mixed groups | Factors promoting the child’s participation in school, home and therapy |

| Interview 3. | Participants in their own groups | Factors preventing the child’s participation in school, home, and therapy |

| Interview 4. | Participants in mixed groups | Factors of collaboration promoting participation of a child with disability |

| Interview 5. | All together | Factors of collaboration promoting participation of a child with disability working towards participation in adulthood |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kinnunen, A.; Jeglinsky, I.; Vänskä, N.; Lehtonen, K.; Sipari, S. The Importance of Collaboration in Pediatric Rehabilitation for the Construction of Participation: The Views of Parents and Professionals. Disabilities 2021, 1, 459-470. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities1040032

Kinnunen A, Jeglinsky I, Vänskä N, Lehtonen K, Sipari S. The Importance of Collaboration in Pediatric Rehabilitation for the Construction of Participation: The Views of Parents and Professionals. Disabilities. 2021; 1(4):459-470. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities1040032

Chicago/Turabian StyleKinnunen, Anu, Ira Jeglinsky, Nea Vänskä, Krista Lehtonen, and Salla Sipari. 2021. "The Importance of Collaboration in Pediatric Rehabilitation for the Construction of Participation: The Views of Parents and Professionals" Disabilities 1, no. 4: 459-470. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities1040032

APA StyleKinnunen, A., Jeglinsky, I., Vänskä, N., Lehtonen, K., & Sipari, S. (2021). The Importance of Collaboration in Pediatric Rehabilitation for the Construction of Participation: The Views of Parents and Professionals. Disabilities, 1(4), 459-470. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities1040032