Abstract

Purpose: In Ireland, the complex needs of people with Spina Bifida and/or Hydrocephalus (SB and/or H) are treated across primary care and tertiary specialist services. Traditionally, there has been much variation in how primary care services are delivered. To increase equity, ‘Progressing Disability Services for Children and Young People’ is a policy which is being implemented to reconfigure children’s services into multidisciplinary teams, for all disabilities. These changes, and an apparent discontinuity of support in the transition to adult services, requires further research exploring service delivery processes. Method: This study explored parents’ perspectives of support services for people with SB and/or H. Eight parents of people with SB and/or H participated in semi-structured interviews which were transcribed and analysed using thematic analysis. Results: Six themes were generated: (1) Difficulty accessing services; (2) Impact of waiting lists; (3) Onus on parents; (4) Importance of communication; (5) Reduced service provision following the implementation of ‘Progressing Disability Services’; and (6) Lack of adult services. Conclusions: While the service redesign for people with SB and/or H and their families is still in the implementation stage, this research contributes to the evolution of these changes by identifying the enhancing aspects such as effective communication and the inhibiting aspects including a parent’s perception of increased responsibility for supporting their family member and barriers in access to services.

1. Introduction

Ireland has one of the highest rates of pregnancies affected by Neural Tube Defect (NTD) in the world [1]. In 2011, the incidence was 1.17 per 1000 births; almost half of which were diagnosed with Spina Bifida (SB) [2]. Given the high prevalence and complex needs of this group it is necessary to ensure holistic and adequate support services across the lifespan [3]. In Ireland, children’s disability services are currently being reconfigured [4] and it is therefore timely to conduct research into the public support services for people with Spina Bifida and/or Hydrocephalus as these changes unfold.

Spina Bifida and/or Hydrocephalus (SB and/or H) has a persistent and pervasive multi-systemic effect on physical, neurocognitive, social and psychological functioning of the affected individuals [5,6]. Depending on the level of the lesion on the spinal cord, individuals present with various co-morbidities [7], regular monitoring of which is required to prevent life-threatening complications [2,8,9]. In addition, qualitative and retrospective cohort evidence suggests that people with SB and/or H experience greater instances of social exclusion and depression in comparison to their peers [10,11]. Individuals with SB and/or H and their caregivers may also be challenged by heavy physical and emotional care-giving demands [12]. There is a need for ongoing support from diagnosis as parents and families require early practical and emotional assistance to reduce the carer burden [13].

Considering the complex needs of this group, a wide range of specialists including neurosurgeons, urologists, orthopaedic surgeons, nurse specialists, psychologists, occupational therapists and physiotherapists are recognised as being most important in the support of people with SB and/or H [6,13,14]. Despite few studies evaluating its effectiveness, cost or quality, the multidisciplinary clinic remains the model of healthcare delivery for children with SB and/or H [15]. Specialist neurosurgical and multi-disciplinary services are provided in a national clinic located in Dublin; however, these services are only accessible for people up to eighteen years old [13]. Local healthcare services have generally been inconsistent with discrepancies between children and adult services. In some areas, specialised therapy services and supports are offered, to both adults and children, by voluntary organisations. However, this is not uniform across the country.

Traditionally, local health services for children with disabilities in Ireland have been delivered differently across the country [16], as they tend to cater to people with specific diagnoses, resulting in discrepancies when children have different types of disabilities [17]. As part of Progressing Disability Services for Children and Young People, the Health Service Executive aims to reconfigure the services [13] to achieve a national, uniform approach to delivering health services within primary care to children, regardless of their disability or location [4].

The implementation of Progressing Disability Services also demonstrates a move towards family-centred interdisciplinary community teams focused on collaborative working [18], which is consistent with research that suggests a coordinated family-centred approach is associated with parental perceptions of better services [19]. Furthermore, it is in line with the European recommendations for early childhood intervention [20] and common practice in Germany and the United Kingdom [4].

Both parents and service providers have expressed concern regarding the implementation of Progressing Disability Services. For relatively rare conditions, like SB and/or H, the proposed new multi-disciplinary teams, named Disability Network Teams, may not encounter enough cases for professionals to develop or maintain sufficient knowledge of their client’s complex needs and thus they will need to be supported by specialist services [13,14,21]. Parents of children with SB and/or H value specialist knowledge of the disability-specific services rather than generic multi-disciplinary teams and have expressed anxiety and confusion regarding the reconfiguration [13].

Due to advances in neurosurgery, urology, orthopaedics, and rehabilitation, long-term survival for people with SB and/or H has increased dramatically over the past 25 years [12,22]. Today, up to 85% of children born with SB and/or H survive into adulthood [2,12]. Adults with SB and/or H require ongoing person-centred, interdisciplinary support in conjunction with comprehensive medical and surgical management [23]. Similar to the original structure of the children’s services, the services for adults with disabilities varies greatly throughout the country [16], even though people with complex health care needs such as SB and/or H are known to have better health outcomes when accessing primary care services that were accessible and family-centred [24]. Furthermore, there appears to be a discontinuity of support during the transition to adulthood; specialised adult care centres are rare [25]. There is currently no specialist multi-disciplinary service for adults with SB and/or H in Ireland, despite the presence of growing international evidence to support its use [23]. Additionally, the use of a multidisciplinary clinic model across the lifespan is supported by the guidelines for SB healthcare services [26], and the loss of specialist care during the transition into adulthood does have risks, such as failure to maintain adequate follow up after the cessation of specialist care [27]. This may reflect what happens once children in Ireland move into the adult services.

Previous research has identified health and therapy needs as well as the availability of services for children with SB and/or H in Ireland and how this compared to international best practice [13]. This study includes both child and adult services. The aim of this study was to explore parents’ perspectives of support services for people with SB and/or H to gain a more in-depth understanding of the aspects that inhibit or enhance the services for people with SB and/or H. As health and social care services are evolving in Ireland, this research provides an opportunity to obtain the perspective of the service-users in evaluating these changes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This qualitative research was informed by phenomenology which is used to describe particular phenomena as lived experience [28,29]. Phenomenology and thematic analysis are closely aligned and historically linked, therefore phenomenology was used as an overarching theoretical framework to inform the analysis, rather than phenomenology in a more traditional sense to explore the parents’ lived experiences [30]. The study sought to understand those experiences from the perspective of those who have direct experience [31], through first-person accounts [32]. Describing and understanding how people make sense of their lives through an exploration of their unique perspectives is central to the philosophy of qualitative methodology [33].

Data analysis was conducted using Braun and Clarke’s six phases of thematic analysis [34]. Thematic analysis was deemed most appropriate for this research as it allows the researcher to identify and analyse patterns or themes in qualitative data [34]. Braun and Clarke [34] describe thematic analysis as a method independent of theory and epistemology, therefore it is a useful and flexible research tool for providing a detailed account of the data regardless of theoretical approach. This research is reported according to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) [35].

2.2. Participant Recruitment

Ethical approval was granted by the Faculty of Education and Health Sciences, University of Limerick Research Ethics Committee (EHS_2016_04_06). A convenience sample of parents of people with SB and/or H was recruited via the Mid-West Spina Bifida and Hydrocephalus Association and the Spina Bifida and Hydrocephalus Ireland (SBHI) membership. Recruitment invitations were sent out via their email database and social media. The researchers also attended the SBHI national conference to recruit participants.

Parents of both children and adults were recruited so as to gather a broad perspective of the support services across the lifespan. While parents of young children would be able to offer their perspective of the current children’s support services, it was thought that parents of older children and adults would offer a perspective of the previous support service structure, transitions to the new structure and the adult services. The study was open to all parents, however, only mothers volunteered. Eight mothers contacted the researchers and were provided with detailed information about the nature, purpose, benefits and risks of the research project via post or email. Participants were informed that given the small community of people affected by SB in Ireland, complete anonymity may not be possible but that all identifiable details would be removed from the transcripts. The participants returned signed consent forms in person or via post prior to participation.

2.3. Data Collection

Data were collected via semi-structured interviews, lasting approximately 1 h. Parents were initially invited to partake in face-to-face interviews, however, due to limited parent availability the parents were given the option of telephone interviews. The interview guide was drawn from a political Activities of Daily Living (pADL) framework [36,37].

Five interviews were completed in person and three were completed via telephone. Both face-to-face and telephone interviewing are considered to be advantageous in terms of providing rich qualitative accounts [38]. While it can be more difficult to develop rapport over the phone rather than in person, telephone interviews are particularly useful when a sample is geographically dispersed [38], as was the case in this study. Interviews took place at a time convenient for the participant and all parents who took part in face-to-face interviews opted to come to the University of Limerick. Each interview was audio recorded and later transcribed verbatim. Field notes were also taken by the researcher during and following each interview.

2.4. Data Analysis

The six-phase process of thematic analysis includes familiarisation with the data, coding, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes and writing-up [34]. Familiarization of the data was step 1 and was accomplished by the first author (MB) transcribing the interviews verbatim, reading the transcripts while actively searching for patterns and noting initial observations [34]. Initial coding was performed using NVivo software where code names were applied and particularly rich selections of text were highlighted by MB. Following the coding and collation of data, the codes were sorted into potential themes, which was then discussed at a peer debriefing with the corresponding author and principal investigator (RJG). This was done using post-it notes as visual aids to organize the codes into themes and to ultimately create a thematic map to represent the primary analysis and connections between concepts for discussion between RJG and MB. The themes were then tested and reviewed by looking at whether the themes reflected a compelling and accurate representation of the data [39]. At this point, some concepts and themes, generally related to the complex needs of the condition, were excluded as they were not linked to the research question. Before write-up, the remaining themes were named and defined by writing a detailed analysis of each theme and a refinement of each theme continued into the writing phase with all three authors involved in finalizing them [34].

A number of measures were taken to enhance the rigor of the research by addressing the components of trustworthiness: credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability [33]. Firstly, to ensure credibility, reflexivity and a critical examination of the researcher’s role was vital throughout the research process from planning to write-up [33,40]. During the study, the first author engaged in reflexive writing and discussion with co-authors, to generate awareness about their own actions, feelings and perceptions [41,42]. In addition, the coding and initial analysis were peer reviewed regularly with the second author acting as research supervisor. Transferability and dependability were addressed by outlining a transparent and dense description of the participants and the research process from the beginning of the study [40,43]. Confirmability was achieved by establishing the aforementioned components of trustworthiness [44] and creating an audit trail of field notes and analytical memos throughout the analysis to trace key decisions made and to review the process by which the themes were formed [43,45].

3. Results

All those who expressed an interest were eligible for inclusion. Eight mothers were interviewed. Six were mothers of children and two were mothers of adults. Information about the participants and characteristics of their children are provided in Table 1. Pseudonyms have been used to maintain the privacy of the participants.

Table 1.

Parents and characteristics of people with Spina Bifida and Hydrocephalus.

Five of the eight parents were involved in Dublin-based specialist services though lived outside of Dublin. Each parent spoke very highly of these services and three parents remarked that they were happy to travel for effective, specialist services. The following findings reflect the integrated experiences communicated throughout the study. Findings largely reflect the experiences with local services rather than specialist services. Six broad themes emerged from the thematic analysis of interviews: Difficulty accessing services, Impact of waiting lists, Onus on parents, Importance of communication, Reduced service provision following the implementation of ‘Progressing Disability Services’ and Lack of services for adults.

- (1)

- Difficulty accessing services

All parents discussed the difficulties faced when accessing services. We choose the word ‘difficulty’ here as it represents the barriers, disparity, struggles and reluctance accessing services, which reflects the narratives. Parents expressed feeling uninformed about the available services, unsure of how to access services or reluctant to access supports.

One parent expressed their initial reluctance for assessing support systems, with concerns about the future:

“I suppose, I dislike the possible future. But, I kind of like that as well. I was very reluctant to join the local branch for the first year, or I didn’t want to know anybody else, because I didn’t want to see what she could be like. But, since we have joined, we haverealised that the support systems that were around for the adults when they were children are much worse in the past than what they are now.”(Ellen)

One parent discussed the lack of consistent and sufficient information being provided by professionals:

“You know so it’s [service] not consistent. You’d be ringing up and it’s the best kept secret. That’s what I call it ‘The best kept secret’. Unless you say ‘I know this child that has received that brand of [wheel] chair, blah, blah blah’, they will tell you that [wheel] chair is not available. So, like, the onus is on the parents to find out everything.”(Claire)

The difficulties mentioned were predominantly in relation to preventative or therapeutic treatment. In the face of acute illness like urinary tract infection, such barriers were not an issue as emergency services were said to be easily accessible. Several parents remarked that once they overcame the barriers to accessing services, the quality of the service was very high:

“Once you get into a service it seems to be brilliant, it’s just knowing that one is there in the first place and then knowing how to access it. Once you’ve kind of overcome those two hurdles, everything is hunky. So it’s not the service as such you can complain about, it’s the getting to it.”(Catherine)

One parent commented on how good the early intervention services are, but expressed concern as her child got older and became an adult:

“Early intervention is great, it’s fantastic, I couldn’t believe it, it’s everybody, you’ve access to everybody and you do, there’s somebody there but it stops then, its stops. I have a massive fear for when (Sean) get to 16, because as bad as it is now, the services are far better for children than they are adults. What happens there, again go back to that, if you had a co-ordinator that is there, that you had somebody.”(Rachel)

The lack of clear and consistent information about the available services and how to access those services were perceived as significant concerns for parents when engaging with the support services.

- (2)

- Impact of waiting lists

Some parents felt that the presence of lengthy waiting lists for services and assistive technology had a significantly negative impact on their child’s development and level of participation in everyday life. One parent said:

“I know down the line… if she needs a chair and we have to order a wheelchair that can be a quite lengthy process… if the kids are waiting that would slow down their development and their interaction because, you know, they can’t get around as much.”(Ciara)

Another parent, with similar concerns, reported that limited services and waiting lists have already affected the progression of their child’s scoliosis:

“I’m at that stage, like, what is the point, you know. I mean, his spine is curved… He hasn’t had someone look at his spine in about 4 years… and we’re waiting for the appointment for the scoliosis doctor who we’ll be waiting for about 2 or 3 years, at that stage we’ll be nearly going into the adult services and that’s very hit and miss.”(Claire)

The presence of long waiting lists and the potential effect they have on development leaves parents feeling frustrated and discouraged from engaging with the services.

- (3)

- Onus on parents

All parents discussed their responsibility of caring for their child with SB and/or H and the diversity of needs.

One parent spoke about the invisible nature of her son’s SB as he has a low spinal lesion and that sometimes internal infections can be missed:

“(Sean) …he’s running, he’s jumping, he’s walking, so he’s defying all odds really. He’s completely incontinent, he’s got a lot of kidney problems. But physically he’s quite well… But even in terms of school he’s no different to any of the other kids’, there’s things he has to do differently but he’s not singled out by looking at him. Em, but sometimes it might be easier if he was. Because you actually miss out on things, you’re not, I think when you present, “Presenting well” is probably my most hated term in medical terms and everything because it’s what every single clinician will say and even on the reports we get from [name of hospital] “presents well, presents well”. Presents well is the reason we have kidney problems, because on the face of it everything looks well it’s what happens inside and to me that’s the biggest downfall of the whole thing.”(Rachel)

The complex needs of people with SB and/or H meant that some parents have to give up work or reduce their hours in order to care for their children:

“I have no idea how I would even manage going back to work… because she has hydrocephalus, you have to watch for shunt failure… whoever is minding her would have to be fully trained in watching for signs, watching for symptoms.”(Ciara)

In the Disability Network Teams, parents are given home programmes and taught the skills to work with their children on a daily basis. While some parents welcomed being included in the treatment of their child, others questioned the practicality of the approach. In families where both parents are working, parents discussed the pressure to find time to give the level of care that is expected from the service providers and professionals:

“In the [Disability Network Team] where they explained the whole process of…this parent led therapy… I was like great but the vast majority of households- there’s two people working in them… I think that the level of care that is put onto parents is unattainable and, you know, there is an enormous amount of work. Every therapy we seem to go to, I seem to get homework to do with Shane, constantly. And it will be like ‘just 20 min a day’ and when you add it all up there actually isn’t enough hours in the day.”(Alice)

Certain aspects of the services, such as a perception that more was expected of parents with regards to home programmes, caused parents to feel added strain.

- (4)

- Importance of communication

Communication was consistently highlighted as an important motivating factor for continuing to engage with the services. Parents discussed the importance of being provided with reassurance and action plans from professionals and being able to contact professionals in times of emergency or uncertainty. When asked about the most important aspect of the services, one parent said:

“Em, I suppose, it sounds really corny, but the communication… I would say the open communication is one of the best things, I think, or the most important things.”(Alice)

This point was reiterated by another parent emphasising the importance of having reassurance a telephone call away. Parents attending the Disability Network Teams praised the co-ordination of the services in terms of communication. Being assigned a contact person was noted as valuable for communicating plans and progress to other services:

“In the [Disability Network Team]… we have a single link person… which is great. That’s the person you see most regularly, in our situation, that’s the physiotherapist. There’s a formal meeting with the parents… with whoever your link person is, and somebody else and they write down your plan… So that is really advantageous to have that as well that you can give to people who provide care outside of the service like even for [the specialist clinic]… I think that’s brilliant like.”(Alice)

Having open, effective and consistent communication between professionals and parents was seen as a positive aspect of the services.

- (5)

- Reduced service provision following implementation of ‘Progressing Disability Services’

Of the eight parents, only two had experienced the introduction of the new Progressing Disability Services structure and transition to the Disability Network Teams. One parent discussed the differences in the services since introducing the teams. She highlighted a dramatic decrease in the provision of services for her child, however, her main concern was the lack of specialist knowledge from the professionals since creating this network service for all disabilities:

“Actually, his OT said to me, when I asked a few questions about hydrocephalus ‘Oh, I don’t know anything about hydrocephalus.’ Well, you see this is my whole point in progressing disabilities. What good are you to me when you don’t know nothing about it?... you can’t create a service that’s not there out of nothing. That’s what’s happened and unfortunately our children’s health is suffering… Progressing disabilities just isn’t working on the ground.”(Claire)

The same parent was able to articulate similar concerns of other parents relating to the amount of services provided by the Disability Network Teams:

“I thought [the services] were brilliant up to 2010, em, and after 2010 they because non-existent and not only for Jack because I’m involved with a few parents groups and things like that and it seems across the board that people are not getting the services that kids need.”(Claire)

This reflected concerns from other parents about the frequency and level of intervention being offered to children from the Disability Network Teams.

- (6)

- Lack of services for adults

Both of the parents of adults and one parent of a teenager discussed their frustration around the lack of specialist adult services. One parent described the stress she experienced due to the lack of services available for her son:

“I found that stressful because as a parent you intervene with the services and you try to get as much as you can from the services for your child… you’re trying to prevent all these further illnesses from occurring… then you get to eighteen and all these services fall apart. It’s like a waste of services… it just is a complete disaster really.”(Mary)

Parents described the loss of expert knowledge and uncertainty of future services as a source of worry. One parent talked about her reliance on private specialist services as well as therapy services offered by charitable organisations. When faced with difficulty accessing adequate local children’s services, a third parent spoke about their frustration in dealing with the services as her child gets older. She discussed being frustrated and unmotivated to fight for services now knowing that it will become even more difficult when her child turns eighteen:

“Well, I would be on the frustration end of it now, I’m not gone to the stage of ‘What’s the point?’ because the way the [Disability Network Team] is now and then when he comes to the adult services which is even more of a chore.”(Claire)

A common view amongst parents was that the time and effort spent getting their child into the child’s services was lost as the services essentially disappear once the child becomes an adult.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore parents’ perspectives of support services for people with SB and/or H to gain a more in-depth understanding of the aspects that inhibit and enhance these services. The findings indicated that difficulty in accessing services, frustration with waiting lists and the responsibility placed on parents were inhibiting aspects of the services. These inhibiting aspects were reported across the old and revised structures of the services for people with SB and/or H. Effective communication was seen as an enhancing aspect of all services. In particular, parents greatly valued the Disability Network Teams’ approach to communication. Although not all parents had experienced the transition to the Disability Network Teams, those who had expressed their concern over the lack of specialist knowledge and the reduction in frequency of services. The findings of this study also indicated a frustration over the lack of specialist services for adults and concerns about the future of adult services. In relation to these findings, the implementation of Progressing Disability Services, communication, responsibility on parents, and the adult services will be discussed in further detail.

The Progressing Disability Services programme and implementation of the Disability Network Teams is in line with the policy recommendations of the European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education for providing uniform access to early childhood intervention [20]. Qualitative accounts have praised the benefits of early intervention; however, parents have expressed disappointment regarding the reduced frequency of therapy for children as they get older [13]. The lack of specialist knowledge among professionals in the local teams, as well as increased waiting periods identified by parents in this study reflect similar qualitative findings by Governey et al. [13]. The same research stipulated that children with SB and/or H represent only about 5% of a therapist’s active caseload [13], thus impacting on the level of specialism and priority in the service.

While there were concerns about the overall programme, there were also positive responses about aspects of the Disability Network Team. The National Reference Group on the implementation of the Progressing Disability Services programme recommended that, in line with international practice, Disability Network Teams have a key-worker within the team to oversee the coordination of a child’s care, to provide a single point of contact for the family and to organise reviews [18]. This is seen as essential when a child is receiving intervention from a number of agencies including the specialist services [18]. In the current study, a key clinical message is about the role that clear and coordinated communication played in satisfaction with service delivery for parents of people with SB and/or H. In the current and previous service design, parents of people with SB and/or H valued being able to contact trusted professionals for reassurance and information. In particular, the parents of children cited the use of a key-worker in the Disability Network Teams as a facilitating factor for engaging with the services.

The use of a key-worker is supported by collaborative research which engaged both service users and practitioners to determine ‘best practice’ statements for children with complex needs [46]. In a literature review of key-worker systems, a UK based study found that having a key-worker led to improvements in quality of life, reduced levels of parental stress, parent empowerment and better relationships with the services [47]. The review also indicated that a key-worker approach has the capacity to significantly improve services [47]. In agreement with previous research, the current study highlights key-workers as being advantageous in supporting parents to develop plans and co-ordinate care with other services. The use of a key-worker ensures a family-centred model of care [48] and allows the service to focus on the needs of the child and their family rather than the needs of the service [47].

Qualitative research has found that long-term care required by children with SB and/or H can negatively impact the primary caregiver’s health and well-being [49] as well as the family [13]. Parents report struggling against inaccessible environments and inadequate support systems, which should be supportive of them [50]. Delivery of services in a family-centred manner promotes partnerships with parents which is essential in ensuring families are respected and supported [51]. This differs from the traditional child-centred approach where parents’ perspectives were often ignored or they were simply told what to do by practitioners [52]. An interesting finding in the current study was that although services appeared to be family-centred, there was a notable responsibility on parents to co-ordinate care and to complete several home programmes on a daily basis. This finding principally came from parents who were accessing the Disability Network Teams.

The provision of home programmes has been described as a functional and family-centred approach to therapy encompassing parent participation [53,54]. However, with waiting lists, limited resources and access to services, home programmes sometimes become an alternative to one-to-one service provision [52]. Furthermore, previous exploration of parent perceptions of family-centred services implied that parents often prefer not to participate due to limited expertise and often do not comply with home programmes due to competing responsibilities [55,56]. Although parents in this study did not report non-compliance, they did report feeling that there were not enough hours in the day, especially when both parents were working. Contrary to the evidence which supports the use of family-centred services in increasing carer involvement [53], this research highlights the possibility that family-centred care may not always be appropriate depending on the needs of the family and the presence of competing demands.

Moreover, the lack of specialist services for adults with SB and/or H is of major concern for parents. All parents expressed satisfaction with the care provided by the specialist services for their children, however, once individuals turned eighteen they were unable to attend specialist clinics. Research in Canada found that young adults with SB and/or H accessed medical services and were admitted to hospital at a much higher rate than the general population, citing limited access to expert care as a contributing factor [25]. The results of this study, while limited, support the need for ongoing access to expert or specialist services for adults with SB and/or H. More in-depth research with regard to transition and availability of appropriate adult services would be beneficial. Furthermore, the number of children who are now surviving well into adulthood [2] is justification enough for ensuring a continuity of specialist care across the lifespan.

Canadian research suggests that the development of more structured outpatient services with stronger links between primary and tertiary care and a coordinated system of care to support people with SB would considerably reduce hospitalisations [25]. Coordination of care is highly recommended to facilitate a transition into the adult services [12]. It is recommended that service users and their families are taught to co-ordinate their own care to ensure self-sufficiency in adulthood [26]. Parent reports of difficulty accessing services, and in particular not knowing about services, suggests that parents or individuals with SB and/or H in Ireland may not be supported to coordinate their own care.

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

With regard to limitations, this study reflects the viewpoint of mothers within a small and heterogeneous sample of participants, therefore it may not be possible to generalise findings across the population. Due to the heterogeneity of need in this group and the discrepancy of services provided around the country, each parent’s experience of the service provision is unique to their situation. In addition, recruiting a convenience sample through the Mid-West and national SBHI associations may have limited the sample to members of these associations excluding parents of people with SB and/or H who are not linked to any voluntary body.

By interviewing parents, this study obtained the perspective of the parent as a service-user and, by proxy, the perspective of their child as a service-user. There were strengths and limitations to this approach. It allowed for an exploration of the services across the lifespan, however, there are likely to be differences between adults and children in their experiences and understanding of the services [57], and ideally data would have been collected from both parties [58]. A strength of this study was the commitment to enhance its rigour throughout [33] as well as adherence to the principles of phenomenology [29,31,32]. As outlined in the methods section, trustworthiness was achieved through reflexivity, description of the process, keeping an audit trail of analysis and presenting rich representations of the data in this article.

4.2. Recommendations for the Future

The Progressing Disability Services programme is still in the implementation stages in many areas [4], therefore this research can help to contribute to its evaluation and influence future service development. This research can inform current service-delivery particularly in terms of continuing to develop effective communication pathways in multi-disciplinary teams, ensuring that services reduce parent-stress and facilitate care-coordination that empowers the service-user and their families. In conjunction with previous research, this study has highlighted the need for clinicians and policy makers to understand how caring for a child with a disability affects the well-being of parental caregivers. Adequate supports need to be put in place [48] including critically examining the use of the family-centred model. Therapeutic intervention should be embedded within everyday tasks to ease caregiving strain [51] and family circumstances should be considered so that parents are not overwhelmed by the volume of work.

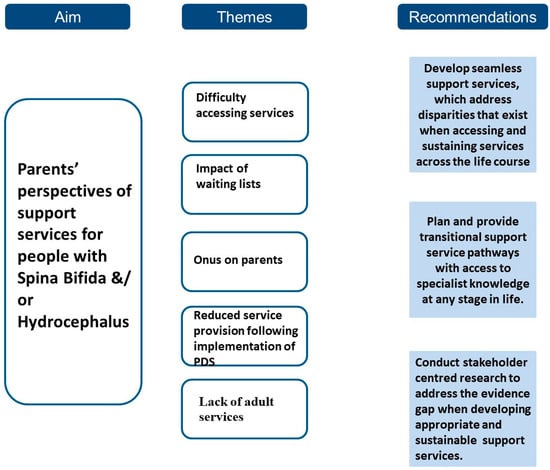

Finally, in considering the restructuring of services, the value of specialist knowledge for complex conditions like SB and/or H needs to be better considered. Access to specialist knowledge and clinicians for optimal management of SB and/or H complications allows both children and adults with SB and/or H to maximize their function and quality of life [12,23]. Furthermore, access to specialist adult services is essential in maintaining health and managing co-morbidities across the lifespan. This is the first study to explore the experiences of interacting with adult services for people with SB and/or H in Ireland. In order to gain a complete picture of the services, further investigation is warranted. Future research should engage service users, service providers and policy developers in order to gain a more comprehensive analysis of Irish healthcare support services for people with SB and/or H and to contribute to the development of sustainable support service strategies for people with SB and/or H across the lifespan. Participatory research methods are recommended in order to maximise user involvement in developing SB and/or H specific services [59] alongside population-based studies comparing outcomes for people with SB and/or H according to different service provision models. Figure 1 presents an overview of the study aim, themes and recommendations.

Figure 1.

Overview of Study: aim, findings and recommendations.

5. Conclusions

Spina Bifida is a complex, life-long condition that requires continuous multi-disciplinary support as well as access to specialist medical and surgical intervention [23]. While the move towards a reconfiguration of children’s services is in line with international practices of equity in service delivery, it is not without its challenges. Exploring the perspectives of parents of people with SB and/or H adds valuable understanding of the service impact on families. In short, access to specialist knowledge and communication are enhancing aspects of the services and greatly valued by this group. In contrast, difficulty accessing services, lack of specialist knowledge and the responsibility placed on parents are the main inhibiting aspects of the services. As the services continue to evolve in Ireland, this research adds to the literature informing current and future service planning and practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.J.G. and M.B.; methodology, R.J.G. and P.B.; validation, M.B., R.J.G. and P.B.; formal analysis, M.B., P.B. and R.J.G.; investigation, M.B. and R.J.G.; resources, R.J.G.; data curation, M.B. and R.J.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B., P.B. and R.J.G.; writing—review and editing, M.B., P.B. and R.J.G.; visualization, R.J.G.; supervision, R.J.G. and P.B.; project administration, R.J.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Faculty of Education and Health Sciences, University of Limerick Research Ethics Committee University of Limerick (V94 T9PX) (EHS_2016_04_06).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to participant consent restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all those who participated in this study. Thank you to the organizations for acting as gatekeepers in recruitment for this study and MSc Occupational Therapy (Professional Qualification) student for assistance with data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

References

- Report of the Scientific Committee of the Food Safety Authority of Ireland: Update Report on Folic Acid and the Prevention of Birth Defects in Ireland. Food Safety Authority of Ireland. 2016. Available online: https://www.fsai.ie/publications_folic_acid_update/ (accessed on 2 April 2017).

- McDonnell, R.; Delany, V.; O’Mahony, M.T.; Mullaney, C.; Lee, B.; Turner, M.J. Neural tube defects in the Republic of Ireland in 2009-11. J. Public Health 2015, 37, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, C.; Brodie, L.; Dicker, J.; Steinbeck, K. Development of health support services for adults with spina bifida. Disabil. Rehabil. 2011, 33, 2381–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Progressing Disability Services for Children and Young People. Health Service Executive (HSE). 2016. Available online: http://www.hse.ie/progressingdisabilityservices/ (accessed on 10 March 2017).

- Holmbeck, G.N.; Devine, K.A. Psychosocial and family functioning in spina bifida. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2010, 16, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brustrom, J.; Thibadeau, J.; John, L. Care coordination in the spina bifida clinic setting: Current practice and future direc-tions. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2012, 26, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barf, H.; Post, M.W.M.; Verhoef, M.; Jennekens-Schinkel, A.; Gooskens, R.H.J.M.; Prevo, A.J.H. Restrictions in social participation of young adults with spina bifida. Disabil. Rehabil. 2009, 31, 921–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liptak, G.S.; Garver, K.; Dosa, N.P. Spina Bifida Grown Up. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2013, 34, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alriksson-Schmidt, A.I.; Thibadeau, J.K.; Swanson, M.E.; Marcus, D.; Carris, K.L.; Siffel, C.; Ward, E. The Natural History of Spina Bifida in Children Pilot Project: Research Protocol. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2013, 2, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicianno, B.E.; Kinback, N.; Bellin, M.H.; Chaikind, L.; Buhari, A.M.; Holmbeck, G.N.; Zabel, T.A.; Donlan, R.M.; Collins, D.M. Depressive symptoms in adults with spina bifida. Rehabil. Psychol. 2015, 60, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, N.; Church, P.; Lyons, J.; McPherson, A.C. A qualitative exploration of the experiences of children with spina bifida and their parents around incontinence and social participation. Child Care Health Dev. 2015, 41, 954–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.G.; Kusminsky, M.; Foley, S.M.; Hobbs, N.; Queally, J.T.; Bauer, S.B.; Kaplan, W.J.; Weitzman, E.R. Strategic directions for transition to adulthood for patients with spina bifida. J. Pediatr. Neurol. 2013, 11, 211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Governey, S.; Culligan, E.; Leonard, J. The Health and Therapy Needs of Children with Spina Bifida in Ireland; Temple Street Childrens’ University Hospital: Dublin, Ireland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Oakeshott, P.; Hunt, G.M.; Poulton, A.; Reid, F. Expectation of life and unexpected death in open spina bifida: A 40-year complete, non-selective, longitudinal cohort study. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2009, 52, 749–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liptak, G.S.; Samra, A. Optimizing health care for children with spina bifida. Dev. Dis. Res. Rev. 2010, 16, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Services for People with Disabilities. Citizen Information Board. 2016. Available online: http://www.citizensinformation.ie/en/health/health_services/health_services_for_people_with_disabilities/health_services_for_people_with_intellectual_physical_or_sensory_disabilities.html (accessed on 8 April 2017).

- Progressing Disabilities Services for Children [Internet]. Inclusion Ireland. 2017. Available online: http://www.inclusionireland.ie/content/page/progressing-disabilities-services-children (accessed on 8 April 2017).

- Report of the National Reference Group on Multidisciplinary Disability Services for Children Aged 5–18. Health Service Executive (HSE). 2009. Available online: http://www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/4/disability/progressingservices/reportsguidancedocs/refgroupmultidisciplinarydeiservchildren.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2017).

- King, G.; King, S.; Rosenbaum, P.; Goffin, R. Family-centered caregiving and well-being of parents of children with disabilities: Linking process with outcome. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 1999, 24, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Early Childhood Intervention (ECI): Key Policy Messages. European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education. 2013. Available online: https://www.european-agency.org/sites/default/files/early-childhood-intervention-key-policy-messages_ECI-policypaper-EN.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2017).

- Progressing Disability Services for Children and Young People: Guidance on Specialist Supports. Health Service Executive (HSE). 2015. Available online: https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/4/disability/progressingservices/GSS.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2017).

- Kaufmann Rauen, K.; Sawin, K.J.; Bartelt, T. Transitioning adolescents and young adults with a chronic health condition to adult healthcare–an exemplar program. Rehabil. Nurs. 2013, 38, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Khan, F.; Amatya, B.; Ng, L. Rehabilitation Outcomes in Persons with Spina Bifida: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Rehabil. Med. 2015, 47, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homer, C.J.; Klatka, K.; Romm, D.; Kuhlthau, K.; Bloom, S.; Newacheck, P.; Van Cleave, J.; Perrin, J. A Review of the Evidence for the Medical Home for Children With Special Health Care Needs. Pediatr 2008, 122, e922–e937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, N.L.; Anselmo, L.A.; Burke, T.A. Youth and young adults with spina bifida: Their utilization of physician and hos-pital services. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 95, 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merkens, M.J. (Ed.) Guidelines for Spina Bifida Health Care Services throughout the Life Span, 3rd ed.; Spina Bifida Association Professional Advisory Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, B.A.; Terbrock, A.; Winters, N. Disbanding a multidisciplinary clinic: Effects on the health care of mye-lomeningocele patients. Pediatr. Neurosurg. 1994, 21, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streubert, H.J.; Carpenter, D.R. Qualitative Research in Nursing: Advancing the Humanistic Imperative; Lip-Pincott: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hesse-Biber, S.N.; Leavy, P. The Practice of Qualitative Research, 2nd ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascal, J.; Johnson, N.; Dore, C. The lived experience of doing phenomenology: Perspectives from beginning health science postgraduate researchers. Qual. Soc. Work 2010, 10, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapp, T. Understanding phenomenology: The lived experience. Br. J. Midwifery 2008, 16, 308–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammell, K.W.; Carpenter, C. Introduction to qualitative research in occupational therapy and physical therapy. In Using Qualitative Research: A Practical Introduction for Occupational and Physical Therapists; Hammell, K.W., Carpenter, C., Dyck, I., Eds.; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 40–52. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronenberg, F.; Algado, S.S.; Pollard, N. Occupational Therapy without Borders: Learning from the Spirit of Survivors; Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gowran, R.J.; Kennan, A.; Marshall, S.; Mulcahy, I.; Mhaille, S.N.; Beasley, S.; Devlin, M. Adopting a Sustainable Community of Practice Model when Developing a Service to Support Patients with Epidermolysis Bullosa (EB): A Stakeholder-Centered Approach. Patient Patient-Centered Outcomes Res. 2014, 8, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, C. Real World Research, 2nd ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Teaching thematic analysis: Overcoming challenges and developing strategies for effective learning. Psychologist 2013, 26, 120–121. [Google Scholar]

- Krefting, L. Rigor in Qualitative Research: The Assessment of Trustworthiness. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 1991, 45, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darawsheh, W. Reflexivity in research: Promoting rigour, reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int. J. Ther. Rehabil. 2014, 21, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhart, M. Representing qualitative data. In Handbook of Complementary Methods in Education Research, 3rd ed.; Green, J.L., Camilli, G., Elmore, P.B., Eds.; American Educational Research Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; pp. 567–581. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, H.; Smith, J. Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research. Évid. Based Nurs. 2015, 18, 34–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, E.; Magilvy, J.K. Qualitative Rigor or Research Validity in Qualitative Research. J. Spéc. Pediatr. Nurs. 2011, 16, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsburgh, D. Evaluation of qualitative research. J. Clin. Nurs. 2003, 12, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, B.; Cummings, J.; Cooper, L. An exploration of best practice in multi-agency working and the experiences of families of children with complex health needs. What works well and what needs to be done to improve practice for the future? J. Clin. Nurs. 2007, 16, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liabo, K.; Newman, T.; Stephens, J. A Review of Key Worker Systems for Children with Disabilities and Development of Information Guides for Parents, Children and Professionals–Summary; Welsh Centre for Learning Disabilities and Barnardo’s eds. Welsh Office for Research and Development; National Assemby of Wales: Cardiff, UK, 2001.

- Mukherjee, S.; Beresford, B.; Sloper, P. Unlocking Key Working: An Analysis and Evaluation of Key Worker Services for Families with Disabled Children; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 1999; ISBN 186134208X. [Google Scholar]

- Grosse, S.D.; Flores, A.L.; Ouyang, L.; Robbins, J.M.; Tilford, J.M. Impact of Spina Bifida on Parental Caregivers: Findings from a Survey of Arkansas Families. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2009, 18, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville-Jan, A. The Problem With Prevention: The Case of Spina Bifida. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2005, 59, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Liptak, G.S.; Orlando, M.; Yingling, J.T. Satisfaction with primary health care received by families of children with devel-opmental disabilities. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2006, 20, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novak, I.; Cusick, A. Home programmes in paediatric occupational therapy for children with cerebral palsy: Where to start? Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2006, 53, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M.; Darrah, J.; Pollock, N. Family-centred functional therapy for children with cerebral palsy: An emerging practice model. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 1998, 18, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franck, L.S.; Callery, P. Re-thinking family-centred care across the continuum of children’s healthcare. Child Care Health Dev. 2004, 30, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcuri, G.G.; McMullan, A.E.; Murray, A.E.; Silver, L.K.; Bergthorson, M.; Dahan-Oliel, N.; Coutinho, F. Perceptions of family-centred services in a paediatric rehabilitation programme: Strengths and complexities from multiple stakeholders. Child Care Health Dev. 2015, 42, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinojosa, J.; Anderson, J.; Strauch, C. Pediatric Occupational Therapy in the Home. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 1988, 42, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Eiser, C.; Morse, R. Can parents rate their child’s health-related quality of life? Results of a systematic review. Qual. Life Res. 2001, 10, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmingsson, H.; Ólafsdóttir, L.B.; Egilson, S.T. Agreements and disagreements between children and their parents in health-related assessments. Disabil. Rehabil. 2016, 39, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lidström, H.; Lindskog-Wallander, M.; Arnemo, E. Using a Participatory Action Research Design to Develop an Application Together with Young Adults with Spina Bifida. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2015, 217, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).