Abstract

Despite the substantial increase in the access of people with disabilities to higher education, university institutions continue to be an exclusive environment for people with intellectual disabilities. This paper aims to present a training programme for the employment and university inclusion of young people with intellectual disabilities at the Pablo de Olavide University in Seville, Spain, under the title “Training for the employment and autonomous life of people with intellectual disabilities”, which was launched in the academic year 2017–2018 and has already completed four editions. The programme includes a hybrid training system with specific university training oriented towards employment and autonomy together with inclusive training in subjects of various university degrees. The training is provided by interdisciplinary university lecturers together with support staff specialised in intervention with people with intellectual disabilities who come from experienced community associations. Other components of the experience include internships in companies, individualised academic tutoring of students, family accompaniment, and community inclusion with the use of the university residence as accommodation. Cognitive accessibility and new technologies are not lacking as supports in the process. This work shows the assessment of the fundamental actors of this experience during the four years of its development, and as a conclusion, it shows a high overall satisfaction with the programme and the radical change observed in the lives of people with intellectual disabilities after their time at the university.

1. Introduction

In a decade, attention to students with disabilities has become a quality standard in the framework of the European Higher Education Area. The National Agency for Quality Assessment and Accreditation includes several aspects related to equal opportunities for students with disabilities in the evaluation and verification of official degrees in Spain. Despite this, universities do not offer the same opportunities to all students with disabilities. People with intellectual disabilities are mostly excluded from the higher education environment.

Recent studies focus on analysing the barriers to achieving the degree of educational inclusion that the non-disabled population achieves [1,2,3,4]; others have focused on access to university studies [5,6,7] or in the attitude of teachers [8], among others. Nowadays, a new trend towards the analysis of positive conditioning factors is beginning [9] which allows the foundations for good performance to be laid.

Since the 1960s and 1970s, public authorities began to assume responsibilities regarding special education [10]. The educational development of people with intellectual disabilities in the Spanish environment can take place in Special Education Centers, segregated from the rest of the students without disabilities, or in ordinary centers with specialized support and inclusive experiences. However, the legislation bets on the principle of normality and inclusion since 2013 [11], encouraging the presence of students in regular centers [12]. In particular, in 2018, the UN alerted Spain that in order to comply with the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities regarding the objectives of inclusive education, special places should be replaced by places in regular schools (More information: https://www.ohchr.org/sp/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=23135&LangID=S, accessed on 22 October 2021).

The different educational levels range from four to twelve years of age with kindergarten and primary education, followed by secondary education up to 16 years of age. All these levels are compulsory and free of charge. However, at the European level, Spain has one of the highest rates of people with disabilities with a low level of education (65.7), surpassed only by Portugal (84.8) and Turkey (86.2) [13]. This means that more than a third of the working-age population with disabilities have primary education (19.1%), obligatory secondary education (59.5%), or no education at all [4,5]. Thus, only 16.9% have higher education, including vocational training and university [13], compared to 36.29% for the non-disabled population [13].

In Spain, Vocational Training is a regulated option of the educational system that, through official qualifications of between 1300 and 2000 h and of various levels (basic vocational training, specific vocational training of intermediate, and higher grade and specialization courses), has the objective of labor insertion with an important role of internships in companies [14]. However, people with intellectual disabilities have difficulties in accessing the system, and those who access it do so at the basic training level. Although vocational training is a primary axis of their itinerary, some studies show the need to develop complementary programs to expand and enrich the educational response in terms of job training [15].

Several experiences show that the training of people with intellectual disabilities in the university environment in general professional skills, with a degree issued by a university, has a positive impact on their autonomy and personal growth and their employability in different business sectors [16]. These experiences aim, on the one hand, to broaden the educational responses for labor market insertion, but fundamentally to investigate formulas for the access of people with intellectual disabilities to higher education. However, although there is an offer of public funding for vocational training, the educational system has not consolidated the financing of these training proposals in universities, depending on funding from entities such as the Once Foundation (Web: https://www.fundaciononce.es/es/que-hacemos/universidad-y-discapacidad, accessed on 22 October 2021).

At the university level, there is once again a large difference between undergraduate and postgraduate students, as shown in the Universia Report [17]. Currently, more than twenty-one thousand people with disabilities are studying at Spanish universities. Of these, more than eighty-five percent are undergraduate students, which means that there are 1.5% of students with disabilities out of the total student body. In postgraduate and Master’s programmes, at present, only 8.87% of the total number of students are with disabilities, which would represent 1% of the total number of postgraduate and Master’s students. Finally, 631 people with disabilities in Spain are currently studying for a doctorate, which represents 0.8% of the total number of students with disabilities at this level of education.

The distribution according to gender is balanced between men and women, although there is a greater presence of men. As for the type of disability, physical or organic disability (30.4%) is predominant, followed by intellectual or developmental disabilities (11.8%) and sensory disability (10%); the least predominant are psychosocial or mental health disabilities (3.9%), although there is a high percentage of students (44%) whose disability is not contemplated in the previous categories or is not recorded.

Although the Universia Report [17] gives a breakdown of the population with intellectual disabilities, there are no data from official sources that show the reality of this student body at the university level. In the case of the National Institute of Statistics, in its study <<The employment of people with disabilities>>, no data are presented on the higher education of people with intellectual disabilities, revealing, in the words of Yerga, Díaz, and Sánchez [18], the predisposition to find people with disabilities at levels between illiteracy, primary, and secondary education. Not surprisingly, in this same statistical series, we can see how there is an increase in the educational level of people with intellectual disabilities since, in 2009, only 26.4% reached secondary education and training and labour insertion programmes, while in 2018, these data increased to 38.9%.

Some experiences, such as the On Campus programme at the University of Alberta in Canada [19], pioneer in programs that use the university as a training environment, have served as a model for job training programs for people with intellectual disabilities at the international level [20]. Moreover, the Think College Initiative at Boston University, the Hill’s Up Program, Flinders University in Adelaide (Australia), or Trinity College at the University of Dublin [20,21] support the use of the University as an inclusive learning environment and show the programmatic and academic options. In the Spanish context, there is the Autonomous University of Madrid with its Promentor Program [22] or the “Todos somos Campus” program of the University of Murcia [23] with financing from the European Social Fund and the ONCE Foundation. With different financing, but with the same objectives, are the Universidad Pontificia de Comillas with the Demaos Project, the Capacitas program of the Universidad Católica San Antonio de Murcia, or the Universidad de La Coruña with the program called Espazo Compartido (Shared Space).

In Spain, experiences developed by the Autonomous University of Madrid, the University of Comillas, or the University of A Coruña, provide comparative conclusions, both on the use of the University as an inclusive learning environment for people with disabilities and with opportunities to improve employability [20]. Although these experiences have been approached from existing vocational training models, they show that the university is a privileged environment for interaction with peers and restoration of self-esteem, for students with poor success in vocational training programs in the educational system. These experiences have been nurtured as a result of the extension of inclusion initiatives in Spanish universities by the ONCE Foundation programme, and have been showing their success in empowering people with intellectual functional diversity [24].

On a qualitative level, Díaz-Jiménez, Terrón-Caro, and Muñoz [21] analysed how these experiences developed in the last decade have favoured changes in students with intellectual disabilities that have had repercussions on their socio-family environment. The authors highlighted the importance of treating students with intellectual disabilities as adult human beings, a practice sometimes little contemplated in the different environments in which they have been developing.

Faced with this reality, and with the aim of advancing the inclusion of people with disabilities in the university environment, increasing the number of people with disabilities with higher education and promoting their professional inclusion in technical and qualified jobs, the Unidiversity Programme of the ONCE Foundation was created with European Social Funds. Framed in compliance with article 24 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and with the fulfilment of goals 4, 8, and 17 of the Sustainable Development Agenda, the first call for applications arose in 2017, in which different universities competed for its implementation. At present, with the start of the 2021–2022 academic year, more than thirty universities and thousands of young people are participating.

This research focuses on the programme developed at the Universidad Pablo de Olavide, in Seville, Spain. This university has been participating in the ONCE Foundation’s Unidiversity programme since its inception in 2017. For its proper development, it has specialised teaching staff and two collaborating entities: Down Seville (Web: https://www.downsevilla.org/, accessed on 22 October 2021) and Paz y Bien (Web: https://pazbien.org/, accessed on 22 October 2021), both specialised in the care and promotion of people with intellectual disabilities.

The project at the Pablo de Olavide University of Seville presented here is a University Extension Diploma, specifically in a Degree called “Training for employment and autonomous life of people with intellectual disabilities” (FEVIDA, Web: https://www.upo.es/fevida/, accessed on 22 October 2021). It has 30 credits, with a total of 225 h in functional, humanistic, and professional subjects. In addition, it has 100 h of supported internships in companies.

In order to promote the inclusion of FEVIDA students in the university environment, on the one hand, inclusive subjects are developed, and on the other, a week of community immersion at the Flora Tristán University Residence. The inclusive subjects are undergraduate subjects from different faculties which FEVIDA students attend, as agreed, all or some classes, in order to get to know specific undergraduate subjects and foster relations between undergraduate and FEVIDA students. On the other hand, the community immersion week at the Flora Tristán University Residence is an experience of autonomous living for a week in which FEVIDA students live completely independently and for this purpose, they have reference students who live in the residence throughout the year.

The purpose of this paper is not to illustrate a model that fills the gaps in the Spanish vocational training system, the assessment of which would be a matter for another analysis, but to show the evidence that the university context can play a role in academic and personal development, a key to the future employability of people who have not usually had access to this stage of the education system.

The following is a longitudinal analysis of the programme’s quality assessments, with a focus on how the COVID-19 pandemic situation has influenced these editions.

2. Methodology of the Training Experience

The objectives of this programme are: (1) to involve the University in the social inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities through training and the improvement of their employability; (2) to provide university training to young people with intellectual disabilities focused on improving their autonomy, their humanistic training, and their labour preparation; (3) to provide these young people with the necessary skills to increase their possibilities of labour insertion, accessing jobs in the modality of employment with support; (4) to provide inclusive experiences and normalisation within the University Community; (5) to facilitate a comprehensive and personalised training so that young people with intellectual disabilities can participate as full members of their community, and (6) to collect continuous information that serves to improve the academic quality of the degree.

The recruitment process is carried out in coordination with associations of people with intellectual disabilities (regular partners of the program). The fundamental access requirement is to present an official certificate of intellectual disability equal to or greater than 33% officially recognized by the competent body of the autonomous community; as well as being between 18 and 29 years old and registered in the national youth guarantee system (public institution for the promotion of youth employment). The selection is made through an in-depth interview with the candidate and his or her selection family. In this interview, social and academic skills, motivation for the course, and specialized support needs are evaluated.

This degree is taught face-to-face on the Campus of the public University Pablo de Olavide of Seville, with five days a week of classes preferably in the morning and located in a classroom of those destined for the Faculty of Social Sciences and those located in areas of great concurrence and passage of students of the Degrees. The pandemic has forced a strategy of blended learning methodology, which accommodates the future health regulations that, at State, Autonomous, or University level, may arise due to COVID-19. In this way, students will be able to continue their studies in order to meet the planned objectives and complete the teaching credits. Nonetheless, it is absolutely advisable to maintain attendance in order to work on the necessary competences and skills. For this purpose, the Universidad Pablo de Olavide has a virtual platform. In addition, the programme is open to the use of other new technologies that facilitate communication and learning through digital teaching innovation. The fact that the on-campus classes are located on campus allows students to participate in university life, establishing collaborative synergies with the degrees of the Faculty of Social Sciences, the Faculty of Experimental Sciences, the Faculty of Business Sciences, and the Faculty of Sports Sciences, as well as others that may be added. These synergies will also be established with the different cultural and social services of the university, such as the radio programme, the volunteer service, the gender classroom, the Service of Attention to Functional Diversity, and the Cultural Extension Service.

The teaching activity is carried out by university lecturers from different disciplines, although mainly linked to the Social Sciences. Together with these, the programme has support staff specialised in the labour insertion of people with intellectual disabilities from the aforementioned specialised external entities.

Specifically, the programme incorporates:

- -

- Universal Learning Design and cognitive accessibility: teaching will be inclusive and with experiences of inclusion with university degrees, with a didactic approach capable of responding to the training needs of all students with a design of accessible activities and materials, with the use of tablet devices for each student that allows accessibility to the virtual classroom. In addition, the teaching materials are adapted for easy reading.

- -

- Flexible groupings: teaching is adapted to the characteristics of the participants, so that general content is taught to the general group and other content will be developed in smaller groups depending on the need for a practical and flexible dynamic to meet the needs of the students.

- -

- Tutorial actions, from a person-centred approach: students have a reference academic tutor with the function of accompanying and guiding students and their families during the course. There is also access to the University’s Virtual Classroom and the Blackboard Ultra Collaborate tool, which allows online tutoring.

- -

- Family accompaniment workshops. Three annual family accompaniment sessions are planned. These are face-to-face workshops for monitoring and working on priority issues for family members.

- -

- Cooperative learning: interaction with students from the Faculty of Social Sciences and other faculties of the UPO, as well as with guest students at the Flora-Tristán Residence Hall, allowing them to carry out academic, social, and cultural activities together: peers in degree subjects; technological references (for ICT support), and community references (companions who support them during their stay at the residence hall).

- -

- Training seminars with guest speakers who are specialists in the specific employment topics of the programme.

- -

- Employment with support when carrying out work placements, with each student being supported by one of the programme’s technicians, so that they can experience the placements in a way that is adapted to their needs and abilities, making progress in the achievement of objectives and new challenges.

- -

- There is a map of collaborating entities for the internships in companies that expands in each edition, adapting to the needs, tastes, and skills of the students. The professional opportunities after completing this degree will be all those specific jobs for people with disabilities in public and private companies that require a basic technical level, as well as any ordinary job in public and private companies that need auxiliary jobs, mainly in the service sector.

- -

- Inclusion in degree courses. Following the commitment of the teaching staff of some subjects of some Olavide degree courses, the map of available subjects is offered and a supply-demand adequacy plan is developed with the student body. With a person-centred approach, affinities and preferences are worked on and each student with a disability chooses the degree subjects to take during their stay at the university.

- -

- The programme carries out business awareness-raising actions, holding an annual Inclusive Business Meeting. The aim of this event is to inform the business community about the objectives of the programme, to raise awareness among the business community about the employability of people with disabilities and to reward inclusive entities that have managed to generate value in their companies by providing work placements for people with intellectual disabilities from the FEVIDA programme. The aim is to recognise the work of these entities that contribute to the practical training of students with intellectual disabilities and that are internship centres for this degree of the Universidad Pablo de Olavide. For this reason, a distinctive plaque as an inclusive company is awarded to the new work experience centres that are joining the FEVIDA programme.

- -

- Awareness-raising and training day for the university community on the empowerment, employment and autonomous life of people with intellectual disabilities through university studies, in which students from previous editions and their families, as well as collaborating entities, share their experiences with actors from the university community in a conference format and training proposals.

With regard to the training contents, Table 1 details the subjects that make up the training.

Table 1.

FEVIDA subjects.

Regarding people with intellectual disabilities, the four editions that have been developed so far (2017–2018, 2018–2019, 2019–2020, and 2020–2021) have allowed access to 66 young people with moderate or mild intellectual disabilities—The first has a cognitive delay and a slight affectation in the sensorimotor field that slows learning, but is not exclusive. The person with moderate intellectual disability needs more support to develop his/her autonomy and learning. Of all the students, 56% are women and 44% are men. With regard to age, 46% of the sample (30 people) are aged between 19 and 22, followed by 30% aged between 27 and 30 (20 people), and finally the age group with the least representation is aged 23 to 26 with a total of 16 people, which represents 24% of the student body.

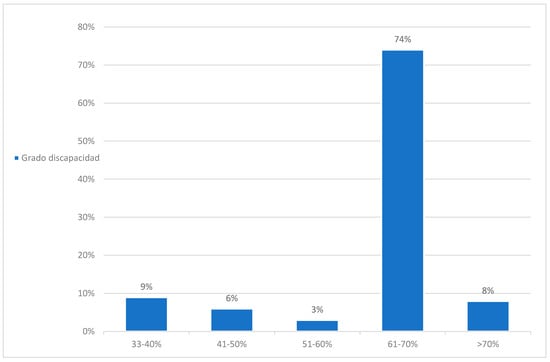

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the degree of recognised disability (official Spanish scale), which ranges from 33% to 89%. The majority of students are in the 61% to 70% disability range, which includes specifically 49 people. The following figure shows the representation of the degree of disability of all the students in the sample. However, on some occasions, this intellectual disability was accompanied by visual impairment, specifically in two cases. There is also a high frequency of students diagnosed with autism spectrum syndrome.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the sample according to the degree of disability. Source: own elaboration.

Regarding the previous educational level of the students at the time of the start of the project, the majority had Compulsory Secondary Education, 39% of the total, followed by studies in Vocational Training or Intermediate Degrees, with a representation of 23%. On the other hand, 17% of the pupils had a basic or primary education diploma, 12% had studied in an Initial Vocational Qualification Programme, and 9% had obtained the ESO diploma through other types of programmes.

3. Excellent Evaluation of the Experience

The evaluation of the programme is approached from a methodological, quantitative, and qualitative complementarity. The quantitative approach allows us to generalise results in a broad way and to obtain a broad view of the phenomenon to be studied, among others. The qualitative methodology allows us to know in greater depth the causes of the changes that occur in the Pablo de Olavide University as an inclusive learning environment, allowing us a better contextualisation of the environment or environment and a more natural and holistic view of the phenomenon to be studied, among many other aspects [20]. The process has been developed in several phases: establishment of the analytical framework; design of the instruments; data collection; data analysis; and preparation of the report and dissemination of the results. The techniques used to collect the data included quality satisfaction questionnaires for family members, pupils, and teachers, group interviews with family members and pupils and individual interviews.

Each year, the opinion of the programme’s stakeholders (students with and without disabilities, teachers and family members) regarding the implementation of the training programme has been taken into account by means of quality surveys carried out at the end of each academic year. These surveys measure six dimensions (1) objectives and content, (2) methodology, (3) teaching, (4) material and teaching aids, (5) usefulness, and (6) overall evaluation of the course and are designed by the university for all the continuing education programmes that it offers in order to analyse the achievement of the general and specific objectives of the programme.

Upon longitudinal analysis of the results of these surveys among the 66 students who have participated in the training in its four editions, 2017–2021 courses, two series have been differentiated to detect the possible influence by the health emergency situation caused by COVID-19. On the one hand, the 2017–2018 and 2018–2019 academic years were compared to the 2019–2020 and 2020–2021 academic years, the former being interrupted by the emergency situation and the latter having taken place during the emergency situation.

From the observations (open-ended questions that provide a qualitative view) of the questionnaires, the degree lecturers indicate as positive aspects of the experience the possibility of sharing time with the students, the inclusion in subjects of other degrees of the university, and the excellent disposition and motivation of the students in the training sessions. On the other hand, they point out the difficulties of online training during the confinement due to the pandemic.

Likewise, non-disabled undergraduate students who have shared classrooms with students with intellectual disabilities understand that inclusive education for all students is a priority, a right, and an obligation in a fair and democratic model of society. As students, they need to receive information about all kinds of diversity and different supports. The greatest interest is shown in attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder, disruptive impulse control and behavioural disorders, and cognitive functional diversity. In order to favour inclusion in the classroom, they mainly propose to create collaborative work activities among students and flexible activities that can be carried out by all students.

In general, the degree of satisfaction with the experience of including students from the FEVIDA programme in the degree course that they have taken is: 78.9% very satisfied, followed by 21.1% who are satisfied. Below are some testimonies from non-disabled students pursuing university degrees.

“I have personally learned many things from talking to them. The kids I have worked with see life with more optimism, they go to class with much more enthusiasm than the rest and they participate much more. Something as simple as putting the camera in the classroom, they don’t care, but the rest of us didn’t. I already thought that we have more to learn than that. I already thought that we have more to learn from them than they have to learn from us, but thanks to this year’s course, I have been able to prove it”.(Student of the Faculty of Social Sciences, academic year 2020–2021)

“Since I was lucky enough to volunteer with people with functional diversity, I began to really empathise and to value all the good aspects that these incredible people can bring to us. Being able to share moments with the students of FEVIDA has been a magnificent experience from which I have been able to learn a lot from them, my colleagues, who have made the classes more enjoyable and above all have given us great moments and a lot of information necessary to know about them and what they feel as people. I am very grateful to have been part of this beautiful subject and adventure”.(Student of the Faculty of Social Sciences, academic year 2020–2021)

“Learning for a future” (Student of the Faculty of Sports Science, academic year 2020–2021)

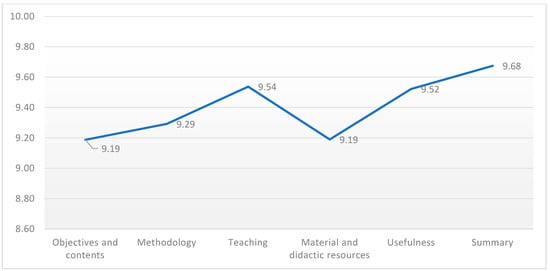

Regarding the assessment of students with intellectual disabilities (n = 66), a longitudinal analysis through arithmetic averages allows us to know the overall satisfaction of students in the four editions. As can be seen in Figure 2, all the items obtain a score higher than 9 but, on average, the overall evaluation of the course and the teaching are the most highly valued. Thus, the knowledge of the teaching staff, the activities carried out in class and the tasks sent home, and the resolution of the doubts raised were rewarded.

Figure 2.

Student assessment of four editions (frequency analysis) Source: own elaboration (n = 66; descriptive statistics, mean).

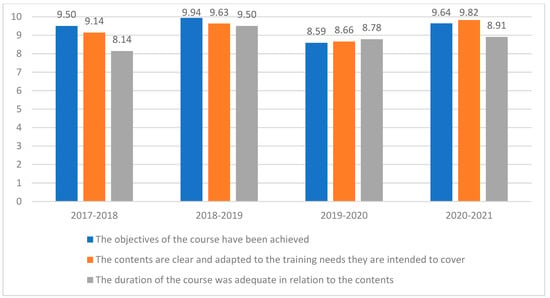

In general, students with intellectual disabilities show a high level of satisfaction with the programme. On the other hand, the achievement of the objectives and contents set out in a privately funded degree is, to a large extent, a form of justification. However, Figure 3 shows that these objectives have been met in all editions, although there is a difference between the time of the pandemic of COVID-19 (academic years 2019–2020 and 2020–2021) and the other two editions. The lowest overall evaluations with respect to the objectives are found in the 2019–2020 academic year, possibly due to the change of modality due to the pandemic, a fact that has improved considerably in the 2020–2021 academic year due to the increased capacity for foresight in the face of the combination of face-to-face and online modality.

Figure 3.

Objectives and contents of the university programme in all four editions. Source: own elaboration (n = 66).

There is a constant drop in scores when talking about the duration of the course, a fact that the students show constantly in all editions, as the programme lasts one academic year and they demand two or more years at the university.

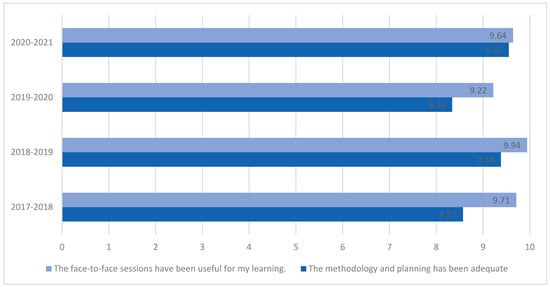

In terms of methodology, there are two moments with low scores: the first and the third edition. This may be explained by the inexperience in the development of the programme, initially, and by the appearance of the emergency situation due to COVID-19 in the third edition. In terms of the usefulness of the face-to-face sessions, a slight decrease can be observed in the editions that have coexisted with COVID-19, more marked in the third edition. Figure 4 shows in detail the constant in terms of the usefulness of face-to-face sessions and the variance in methodology and planning.

Figure 4.

Evaluation of the methodology in the four editions. Source: own elaboration (n = 66).

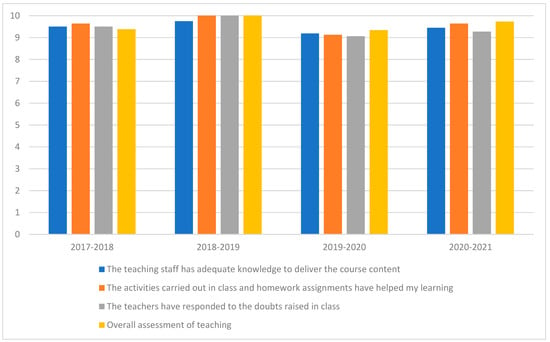

The evaluation of the teaching allows us to know how the information is reaching the students; thus, each year’s specific training is carried out for the teaching staff with the intention of improving the way in which classes are taught and communications are established between the teaching staff and the students, always in the interest of promoting an inclusive environment. Figure 5 shows how there is greater satisfaction with the different aspects related to teaching in the first, second, and fourth editions, while the third edition is affected, possibly due to the occurrence of COVID-19 and the change of modality from face-to-face to online.

Figure 5.

Assessment of teaching in the four editions. Source: own elaboration (n = 66).

As can be seen in the figure above, in the second edition, the overall satisfaction is 9.94. The worst average is for the 2019–2020 academic year, with an average of 9.18 in all the sections referring to teaching, although when asked about the overall assessment of the teaching, the mark obtained is 9.34, which is in line with the rest of the editions, especially the first one.

The second best evaluation was given to the fourth edition, which obtained an average score of 9.52, compared to the 9.51 of the first edition.

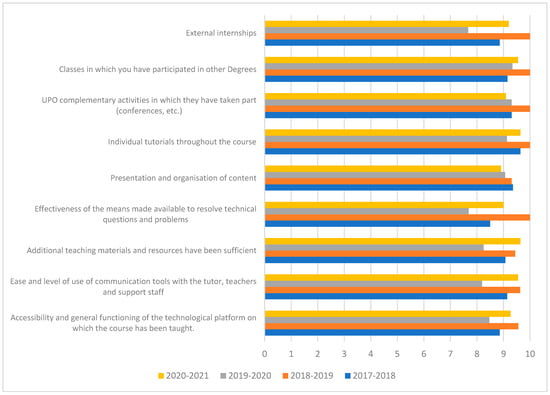

On the other hand, the evaluation of the material and didactic resources includes a number of specifications that allow us to analyse possible specific improvements for the development of the programme.

The most highly valued elements are the individual tutorials throughout the course, which obtained an average of 9.60 in the four editions, reaching a score of 10 in the second edition. This is followed by the classes of other degrees in which you have participated, which, although in the second edition obtained a 10, in the third and fourth editions increased with respect to the first edition, coinciding with the incorporation of new degrees from different faculties as the project is consolidated within the university.

With regard to the material and didactic resources in Figure 6, the elements with the lowest score are those related to the effectiveness of the resources made available to students to resolve doubts and technical problems, with an average score of 8.80. On the other hand, the external placements carried out obtained an average mark of 8.93 in the four editions. With regard to external placements, in the editions with a health emergency situation due to COVID-19, it was impossible to carry them out, thus specialised workshops were given to acquire the skills and knowledge that would have been developed in these placements. However, due to the special characteristics of the 2019–2020 academic year, in which it was decided to postpone the placements for three months, but finally it was not possible to carry them out, the score obtained was the lowest of the entire evaluation: 7.67. On the other hand, and in equal conditions, without external internships in companies, the students of the fourth edition evaluate this employability workshop with a 9.20.

Figure 6.

Evaluation of the material and didactic means in the four editions. Source: own elaboration (n = 66).

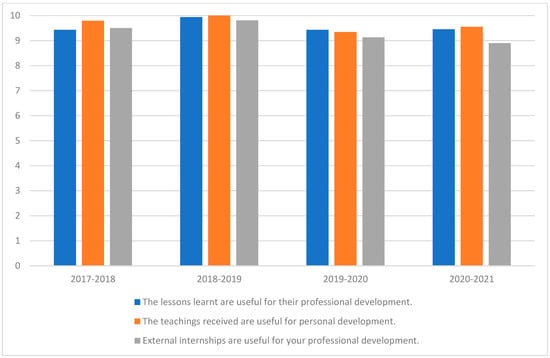

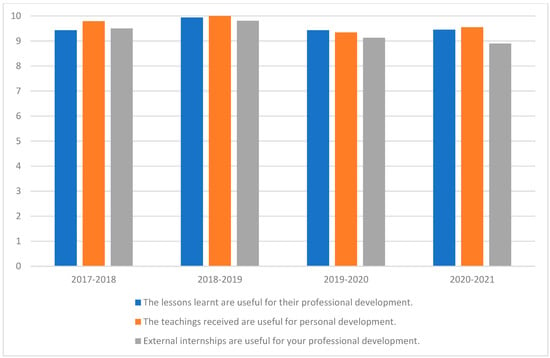

On the other hand, the usefulness perceived by the students for their professional development and their personal training shows the need and capacity of promotion of young people with intellectual disabilities. Again, although the valuation on the usefulness for their professional development is higher than 9 in all the cases, in the first and third edition, there is a decrease of this (9.43). Regarding the usefulness for personal training, there is a decrease in the evaluation in the third and fourth edition with respect to the first two editions.

As can be seen in Figure 7, in line with the above, the usefulness of external placements for professional development is considerably lower in the fourth edition than in previous editions, and a decrease can also be observed in the third edition. Both were possibly influenced by the implementation of employability workshops instead of external placements in companies.

Figure 7.

Evaluation of usefulness in the four editions. Source: own elaboration (n = 66).

Finally, although at this point, we have already obtained an overview of the specific changes and considerations of the different editions based on the students’ evaluations, Figure 8 below shows the high overall satisfaction of the students in the four editions, which increases from the first to the second, and from the third to the fourth, respectively.

Figure 8.

Overall evaluation of the course of all four editions. Source: own elaboration.

The first and third editions have shared some coincidences throughout these results that could be explained, as previously expressed, by the start of the project and the pandemic situation, respectively, always with the capacity for improvement in subsequent editions.

If we take into account the qualitative evaluation such as the interviews, the results obtained have been very satisfactory for each and every one of the agents who have participated directly or indirectly in the course, among which we can point out: the teaching staff, the students, and their families. In particular, the students have shown great interest throughout the process due to the repercussions that the programme has had on their lives.

In order to show the evolution and the students’ perception of the programme, we will rely on the speeches presented by the students themselves in some of the group interviews.

Since the beginning of the course, they have managed to establish social links not only with the students on the course, but also with the university community as a whole, creating a strong sense of belonging to the university: “we are now part of the UPO, and I am happy” (Participant 1), which shows the achievement of one of the main objectives of the programme, which is “To provide inclusive experiences and normalisation within the University Community”.

Likewise, the relationships that they have established with their classmates have allowed them to feel free to be themselves and to show all their weaknesses, fears, insecurities, strengths, etc. “I opened my heart and let out everything I had to let out” (Participant 2), without being afraid of being judged or being limited by the barriers that disability, society, relatives…, impose on them:

“Disability often sets limits for us, and sometimes it doesn’t […] but often we set limits for ourselves…”.(Participant 2)

“[…] the family also sometimes, your own family […]”.(Participant 7)

“[…] societies put them on us and make us believe that we can’t”.(Participant 6)

In this line, the development of the course has achieved another of the proposed general objectives, which is “to provide university training to young people with intellectual disabilities focused on improving their autonomy, their humanistic training and their labour preparation”. Even before starting the training, the students had high expectations in relation to personal autonomy, as 93.3% of them considered that they would be more autonomous once the programme was finished. They assured that the course would help them “to look for a job and to be able to be autonomous”.

These expectations have been fulfilled. Their participation in FEVIDA has contributed to their empowerment:

“Look, I’ve managed to get to university”, you didn’t think that you yourself set limits and say “I’m going to university…” but look, you say to yourself “I’m here, so it must be because I can”.(Participant 6)

It has also helped them to break down the fears and barriers they had imposed on themselves,

“Because apart from having several fields open it also gives you that dream to say and ok, I am here at university, and I am here studying and for the achievement that you have done for many years of your life and you face a fear that you had never thought about until you actually get to the place and the time will come to say here we are, here we are going to study and here we are going to learn new things”.(Participant 2)

It is for this reason that one of the items most highly valued by the students in the final questionnaire was “the teaching received is useful for personal training”.

In relation to the objective “To provide these young people with the necessary skills to increase their chances of finding employment, accessing jobs in the supported employment modality”, we must point out that the results have been very satisfactory. All the students have carried out external internships in different entities or specific employability seminars to achieve the objectives of these internships.

During these internships or seminars, the students have managed to acquire competences related to: social and labour commitments, management of information about labour resources, or critical analysis of employment opportunities and life options. This is why the students have highly valued these internships and seminars.

The students value the training received at the University very positively, as it will allow them to “acquire autonomy and more qualifications, more curriculum, more aggregate, more things to get hired” (Participant 3).

This vision has positively influenced their self-concept, making them feel more capable and empowered, not only to work, but also to live independently:

“[…] apart from meeting a lot of people from the university, well you are learning to live on your own and that is very important”.(Participant 1)

After this experience, they feel that they have “more self-confidence” (Participant 6). In most cases, before starting the course, the students did not see themselves as being able to live independently; however, after the experience of one of the activities organised within the framework of FEVIDA, which consisted of living for a week in a university residence with other students, it has meant a change in their perception “a barrier that I have broken is the fear of living alone” (Participant 1).

However, for many of the students, the implementation of this training has not only favoured their autonomy and self-concept in complex issues such as independence from the family home, but it has also helped them to face everyday life situations that they did not dare to face before. For example, some students had never used public transport without being accompanied by another person to supervise them, but from the beginning of the course, many of them had to face this situation “I come alone” (Participant 5).

These advances have favoured not only the pupils, but also the family. Firstly, as pupils feel more autonomous, they have demanded more freedom in the family nucleus “I believe that parents have to be aware that although we are their children, their children grow up” (Participant 7), claiming that personal space and independence that they had not had until now. Secondly, feeling that they are capable of carrying out certain activities that they previously considered impossible and seeing that their family supports them and trusts them has significantly improved their self-esteem:

“I think that the best thing that we are going to have for me is to live alone in the residence, in the Flora de Tristán, I think that is the most important thing for me, because I have seen that my mother trusts me to live alone”.(GD Participant 1)

In turn, the family also considers that the experience has been very positive due to the impact that it has had on the students, as shown by the data collected in the questionnaire given to the families: “I consider the implementation of this programme at the University to be very important and of great benefit. It has made great progress in the people with disabilities who have attended the course”. However, they are of the opinion that the duration has not been adequate as “it would be advisable to extend the rest time and they could stay for more years” and in particular, they have pointed out some specific activities that should be developed for a longer period of time; among them, we highlight the experience in the student residence “I should have more time” (Participant 5) […] “Or do another course, but with more time” (Participant 7). This idea, shared by both pupils and families, is one of the lowest rated items, as we have seen above.

On the other hand, students also request more dedication to tasks related to getting out of the classroom, “one day we have to go on an excursion” (GD Participant 4), and interact with other people in the university community “we ourselves would do an event here so that all the people from the university know about us, and so that we have more contact with people from the university, with teachers who give other types of classes” (Participant 2).

Although there are certain issues that need to be improved, such as the length of the course, overall, the experience has been very satisfactory in both operational and substantive terms.

4. Discussion

Programmes such as the one developed at the Pablo de Olavide University, according to Díaz, Terrón, and Muñoz [21], show that these initiatives provide opportunities for the acquisition of academic excellence, personal development, and the acquisition of democratic values, as well as respect for the human rights of the undergraduate students who participate and the teaching staff involved. In relation to this statement, we can observe the high valuation of students with intellectual disabilities regarding teaching (9.61) and individual tutorials (9.60), as well as the usefulness of teaching for their personal (9.67) and professional training (9.56). The classes shared with other degrees (9.51) and the face-to-face FEVIDA classes (9.61) are also highly rated, and both are fundamental to progress towards an inclusive higher education environment.

As has been proven in the four editions, the University can become an important agent of social inclusion, as it allows for the sharing of spaces for training, socialisation, learning, and growth between students with and without disabilities, and increases the options for mutual enrichment in the university community in particular and the transmission of the value of respect for diversity to society in general.

The limitations of the study are mainly due to the methodology used, as it could be complemented by qualitative interviews in which proposals for improvement could be obtained from the students themselves. However, as these interviews have been carried out through individual tutorials and family workshops, this limitation gives rise to the possibility of a new study that compares, with the same longitudinal character, the discourses of pupils and families with the programme’s quality data.

Future research is also pending on the differentiation in the entry into the labour market of graduates within and without the context of the pandemic, as there are studies that already warn of the serious employment consequences for this population in the coming years [25]. Although the issue of transportation and mobility is not specifically addressed in these programs, based on the results, the autonomous movement of students has turned out to be a significant variable. Therefore, it is suggested to incorporate it in other studies and research as well as in university programs as an element of independent living.

Hosting these programs in universities in the medium and long term improves the academic, work, and life skills of people with intellectual disabilities; the specific preparation and empowerment of people with intellectual disabilities in universities who have lived with peers, improves their employability in the face of an employer who values the level achieved.

Although this program is a hybrid model, a part of specific training only for students with intellectual disabilities and other inclusive in which students with intellectual disabilities are integrated in subjects of degrees with students without intellectual disabilities, they are still experimental actions, since it is not regulated as usual and with public funding in a stable manner, which generates uncertainty regarding the right of this group to access all levels of education according to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

With these programmes, the University can become an important agent of social inclusion, as it allows the sharing of spaces for training, socialisation, learning, and growth between students with and without disabilities, and for this reason, programmes that take students with intellectual disabilities to higher education are essential, since this is a still very limited space in the educational pathway.

5. Conclusions

A large number of Spanish public universities are developing experiences that allow access to university for this population group, and although a network of inclusive universities is being created, and strategies and objectives are shared, each university is developing proposals based on university autonomy, subsidised by projects from private entities. The first challenge is to consolidate these inclusive strategies in public systems.

For this purpose, the impact of the programmes is being evaluated and in general, on the part of people with intellectual disabilities and their families, there is a great satisfaction with the teaching staff and the overall assessment of the project. This satisfaction is also very high on the part of the teaching staff involved in the programme.

After the implementation of four editions of the Training for employment and autonomous living of people with cognitive functional diversity (FEVIDA) programme, the students of this degree have managed to establish social links, not only with the students of the course, but also with the university community as a whole, creating a strong sense of belonging to the university. Before starting the course, the students had high expectations in relation to personal autonomy, expectations that have been fulfilled given the level of empowerment acquired and the high valuation they have shown of the teaching received [21].

The improvement of employability has been made possible through external internships in various public and private entities. Doing internships as a university student has had a positive influence on their self-concept, making them feel more capable and empowered, not only to work, but also to live autonomously outside the family environment, and they are now able to face everyday situations that they did not even consider before. In addition, it has allowed around 30% of the graduates to be employed one year after completing the program, according to the short-, medium-, and long-term follow-up period carried out, which is recorded in the project’s own reports.

The progress has benefited the families who consider the experience very positive, perceiving in a short period of time important changes in their sons and daughters, and the non-disabled students who have had the opportunity to share the classroom with students with intellectual disabilities. They consider the initiative as an opportunity for academic excellence, personal development, and acquisition of democratic values, as well as respect for human rights.

The experience of the FEVIDA programme at the Pablo de Olavide University analysed in this article, as well as the appropriate development of the Unidiversity Programme at the national level, in which our experience is framed, support the need for these programmes to be anchored in the structures of universities as bridges towards full inclusion in official undergraduate studies in the higher education area.

Author Contributions

The following is a breakdown of the specific tasks carried out by each author: Conceptualization: R.M.D.-J., T.T.-C. and M.D.Y.-M.; Methodology, T.T.-C. and R.M.D.-J.; Validation, R.M.D.-J.; Formal analysis, T.T.-C. and M.D.Y.-M.; Research, T.T.-C.; Draft preparation, M.D.Y.-M.; Writing, revision and editing, R.M.D.-J.; Visualization, T.T.-C.; Supervision, Project Management and Acquisition of funds, R.M.D.-J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

UNIDIVERSITY Program, university training programs for employment aimed at young people with intellectual disabilities registered in the National Youth Guarantee System, funded by the ONCE Foundation and co-financed by the European Social Fund to support employment under the Youth Employment Operational Program (POEJ). Managed by the Pablo de Olavide University Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The ethical review and approval for this study was waived, because it is a program endorsed by the Graduate Commission of the Pablo de Olavide University in a session of 28 April 2021, as the University’s Own Degree Program and in This context, all subjects gave informed consent for inclusion before participating in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. As this was a non-interventional study, all participants were informed to guarantee their anonymity, the purpose of the research, how their data would be used and the non-existence of associated risks.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because it could compromise the privacy of the participant.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Castellana Rosell, M.; Sala Bars, I. La Universidad ante la Diversidad en el aula [The University and Diversity in the Classroom]. Aula Abierta 2005. Available online: https://redined.educacion.gob.es/xmlui/handle/11162/4370 (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- Alcantud, F. La integración de los alumnos con nee en los estudios superiores [The integration of students with disabilities in higher education]. M. López & R. Carbonell (coords.). In La integración educativa y social. Jornadas Nacionales “Veinte años después de la LISMI” [Educational and social integration. National Conference "Twenty years after LISMI".]; Ariel: Barcelona, Spain, 2005; pp. 137–160. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, A.R.; Arregui E, Á.; García-Ruiz, R. La atención a la diversidad en la universidad: El valor de las actitudes [Attention to diversity at university: The value of attitudes]. Rev. Española Orientación Psicopedag. 2014, 25, 44–61. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3382/338232571004.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodríguez Díaz, S.; Cano Esteban, A. Discapacidad y Políticas Públicas. La Experiencia Real de los Jóvenes con Discapacidad en España [Disability and Public Policies. The Real Experience of Young People with Disabilities in Spain]; La Catarata: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Castro de Paz, J.F.; y Abad Morillas, M. La incorporación a los estudios superiores: Situación del alumnado con discapacidad [Entry to higher education: The situation of students with disabilities]. Qurriculum Rev. Teoría Investig. Práctica Educ. 2009, 22, 165–188. [Google Scholar]

- De la Red, N.; De la Puente, R.; Gómez MD, C.; Carro, L. El Acceso a Los Estudios Superiores de Las Personas con Discapacidad Física y Sensorial [Access to Higher Education for People with Physical and Sensory Disabilities]; Secretariado de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Valladolid: Valladolid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nava-Caballero, E.M. El acceso y la integración de los estudiantes con discapacidad en la Universidad de León [The access and the integration of the students with dissability of Leon’s University]. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2012, 23, 293. Available online: https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/RCED/article/download/40030/38468 (accessed on 22 October 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martínez Martín, M.; Bilbao León, M. Los Docentes de la Universidad de Burgos y su Actitud Hacia las Personas con Discapacidad [Teachers at the University of Burgos and Their Attitude towards People with Disabilities]. Siglo Cero 2013, 50–78. Available online: http://riberdis.cedd.net/handle/11181/3770 (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- Ramírez Morera, M. Las condiciones asociadas a la experiencia de éxito universitario de las mujeres con discapacidad [The conditions associated with the experience of university success of women with disabilities, Doctoral Thesis, Repositorio Institucional de la Universidad, San José de Costa Rica 2021. Available online: https://www.kerwa.ucr.ac.cr/handle/10669/83159 (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- Jiménez Lara, A.; Huete García, A. Políticas públicas sobre discapacidad en España. Hacia una perspectiva basada en los derechos [Public policies on disability in Spain. Towards a rights-based perspective]. Política Soc. 2010, 47, 137–152. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11181/6138 (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- Organic Law 8/2013, of December 9, 2013, for the Improvement of Quality [LOMCE] (Spain). Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/2013/BOE-A-2013-12886-consolidado.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- Organic Law 3/2020, of December 29, Amending Organic Law 2/2006, of May 3, 2006, on Education [LOMLOE] (Spain). Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/2020/12/29/3 (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- Observatorio Sobre Discapacidad y Mercado de Trabajo en España (2021) Educación y Formación Profesional [Observatory on Disability and the Labour Market in Spain (2021) Education and Vocational Training]. Available online: https://www.odismet.es/banco-de-datos/3educacion-y-formacion-profesional (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- Brunet, I.; Zavaro, R.B. El modelo de formación profesional en España [The vocational training model in Spain]. Rev. Int. Organ. 2017, 18, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Conte, E.; Delgado-Pastor, L. Un estudio sobre la eficacia en la estructuración de los apoyos en formación profesional para jóvenes con discapacidad intellectual [A study on the effectiveness of structuring support in vocational training for young people with intellectual disabilities]. Siglo Cero. Rev. Española Sobre Discapac. Intelect. 2017, 47, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Díaz-Jiménez, R.M. (dir) Universidad inclusiva. Experiencias con Personas con Diversidad Funcional Cognitiva [Inclusive University. Experiences with People with Cognitive Functional Diversity]; Pirámide: Madrid, Sapin, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fundación Universia. Estudio Sobre el Grado de Inclusión del Sistema Universitario Español Respecto de la Realidad de la Discapacidad [Study on the Degree of Inclusion of the Spanish University System with Regard to the Reality of Disability] (V). 2021. Available online: https://www.fundacionuniversia.net/content/dam/fundacionuniversia/pdf/estudios/V%20Estudio%20Universidad%20y%20Discapacidad%202019-2020%20%20(Accesible).pdf (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- Yerga-Míguez, M.D.; Díaz-Jiménez RY Sánchez-Márquez, I. Capítulo 7. Diversidad funcional cognitiva en la educación superior. Hacia modelos de inclusión en grados universitarios [Chapter 7. Cognitive functional diversity in higher education. Towards models of inclusion in university degrees]. In Educar Para Construir Sociedades Más Inclusivas. Retos y Claves de Futuro [Educating to Build More Inclusive Societies. Challenges and Keys to the Future]; Terrón Caro, T., Ed.; Narcea, S.A. Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, P.; Skinner, L. Inclusive Education: Seven Years of Practice. Dev. Disabil. Bull. 1994, 22, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Cerrillo Martín, R.; Izuzquiza Gasset, D.; Egido Gálvez, I. Inclusión de jóvenes con discapacidad intelectual en la Universidad [Inclusion of young people with intellectual disabilities in the University]. Rev. Investig. Educ. 2013, 11, 41–57. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/4733943.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- Díaz-Jiménez, R.M.; Terrón-Caro, T. Muñoz, R. Universidad y alumnado con diversidad funcional cognitiva. Herramientas para la inclusión en la educación superior [University and students with cognitive functional diversity. Tools for inclusion in higher education]. In Universidad Inclusiva. Experiencias con Personas Con Diversidad Funcional Cognitiva [Inclusive University. Experiences with People with Cognitive Functional Diversity]; Diaz-Jiménez, R.M., Ed.; Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero, P.; Gasset, D.; y García, A. Inclusive education at a Spanish University: The voice of students with intellectual disability. Disabil. Soc. 2020, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmonte, M.L.; Mirete, L.; Galián, B. Evaluación de la pertinencia del título universitario “Todos Somos Campus” dirigido a personas con discapacidad intelectual [Evaluation of the relevance of the university degree “Todos Somos Campus” aimed at people with intellectual disabilities]. Rev. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2020, 95, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Sampieri, R.; Torres, C.P.M. Metodología de la Investigación; McGraw-Hill Interamericana: México DF, Mexico, 2018; Volume 4, pp. 310–386. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, P. Will Disabled Workers Be Winners or Losers in the Post-COVID-19 Labour Market? Disabilities 2021, 1, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).