A Laboratory Set-Up for Hands-On Learning of Heat Transfer Principles in Aerospace Engineering Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

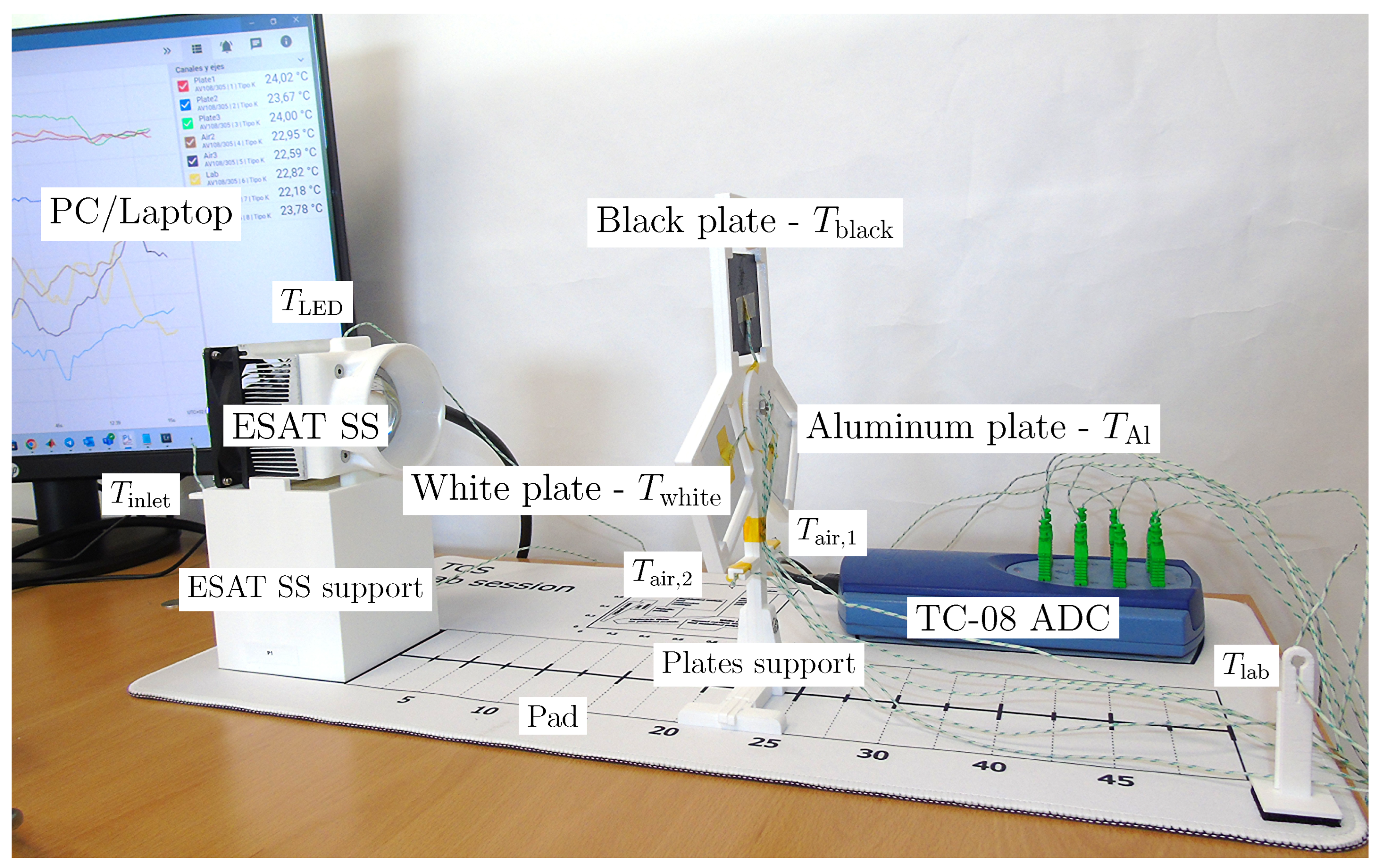

2. Experimental Set-Up

2.1. Aluminum Plates

2.2. ESAT Sun Simulator

2.3. Thermocouples

2.4. Analog-to-Digital Converter and Laptop

3. Concept and Planning of the Laboratory Session

- (30 min) Introduction and preparation of set-up:This includes the connection of thermocouples to the associated channels of the TC-08 ADC and introduction of the associated calibration. Thermocouple readings will be calibrated beforehand so that students simply need to enter the appropriate correction in the PicoLog software.

- (30 min) Thermal characterization of ESAT Sun simulator:Thermocouples will be used to measure the temperature evolution of the ESAT Sun simulator and inlet air of the cooling fan. These data allow estimation of the steady-state temperature of the LED and the heat transfer coefficient that characterizes the convective cooling of the LED–fan system. In the remainder of the session, the characteristic steady-state temperature of the light source will be used as a reference to monitor its adequate functioning.

- (20 min) Radiative heating of the plates at minimum distance from ESAT Sun simulator:Experiments will start by heating the aluminum plates to their maximum expected temperature. In this configuration, the LED–plate radiative interaction is maximized, and the absorptivity can be estimated as well as an initial guess for the emissivity.

- (60 min) Successive experiments at increasing LED–plate distance:The distance between the ESAT Sun simulator and the plates will be increased, and the plate temperature will be allowed to reach a steady state each time. The evolution of the temperature across all experiments will allow for an improved estimate of the emissivity of the plates.

- (30 min) Data processing and estimate of thermo-optical properties:Once completed, all data will be processed to obtain estimates of the heat transfer coefficient of the cooling fan and the thermo-optical properties of the plates.

- (10 min) Wrap-up and concluding remarks.

4. Physical Modeling

4.1. Simplified Model of the ESAT Sun Simulator

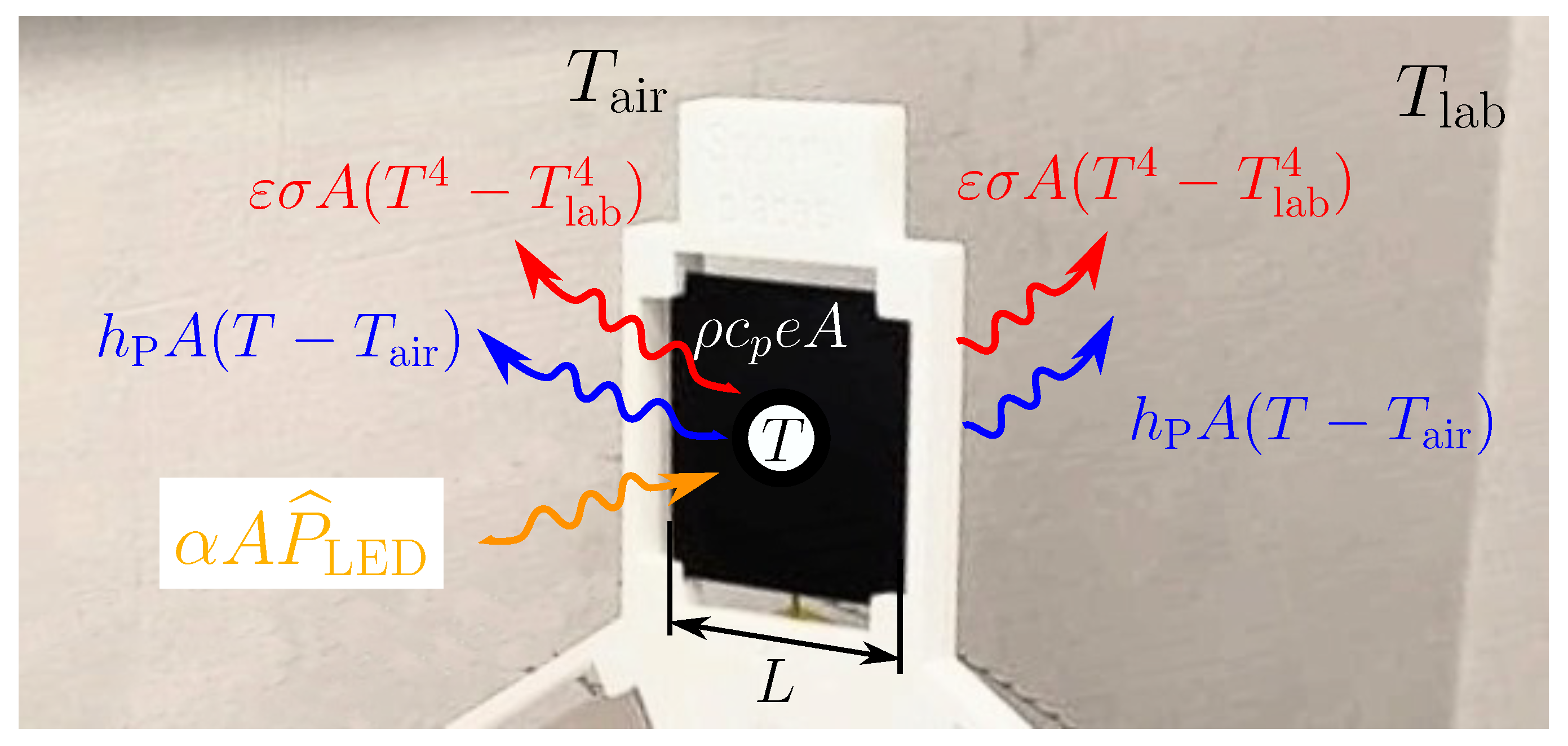

4.2. Simplified Model for the Plates Set-Up

- –

- Exchange with the ESAT Sun simulator:The ESAT Sun simulator emits radiation in the visible spectrum (with a correlated color temperature of ∼6000 K; see Section 4.3) so that the quantity of heat absorbed by the plate iswhere is the absorptivity, is the plate area, and is the average power per surface area received by the plate. The modeling of is described in Section 4.3.

- –

- Radiative exchange with the laboratory:The plate, at temperature T, emits and receives radiation from its surroundings (i.e., the laboratory) primarily along its front and rear surfaces of area A. The difference in heat transferred (to the plate) is given bywhere is the infrared emissivity, W/(m2 K4) is the Stefan–Boltzmann constant, is the temperature of the laboratory, and the factor of 2 accounts for the front and rear plate surfaces.Note that despite the fact that the plate is treated as a gray body with , the radiative interaction with the laboratory can be simplified to that occurring between ideal black bodies. The surface resistance of the laboratory is considered negligible compared with that of the plate since .

- –

- Convective exchange with the surrounding air:As in the case of the ESAT Sun simulator, the plate exchanges heat with the surrounding air along its front and rear surfaces. Using Newton’s law of cooling, this heat can be written aswhere is the convective heat transfer coefficient and is the temperature of the air. In Section 4.4, we describe the estimate of , based on empirical correlations. These correlations already account for the conductive heat exchange with the surrounding air.Note that the effect of the air flow generated by the LED fan on the air surrounding the plates is neglected. This is justified by the fact that fan-driven convection flow exits the dissipator laterally, i.e., horizontally and parallel to the plane of the plates. Furthermore, the minimum distance between the plates and the ESAT light source is cm (see Section 4.3), while the characteristic viscous length is . For the air flow in the fan, we estimate cm, which is several orders of magnitude smaller than ; see Section 2.

4.2.1. Energy Balance and Equilibrium Temperature of the Plate

4.2.2. Estimate of Thermo-Optical Properties

4.3. Modeling the LED–Plate Radiative Interaction

4.4. Heat Transfer Coefficient of Natural Convection

5. Results

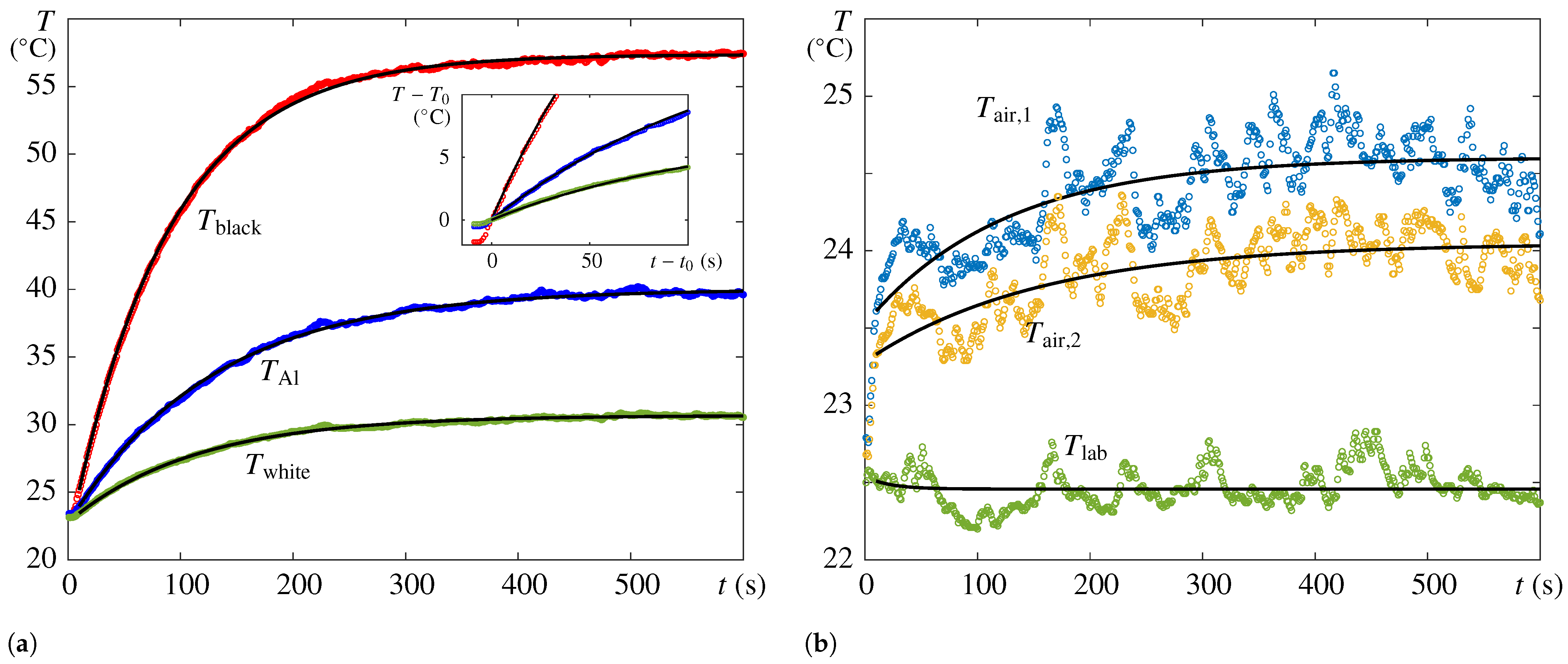

5.1. Thermal Characterization of the ESAT Sun Simulator

5.2. Radiative Heating of the Plates at the Minimum Distance from the ESAT Sun Simulator

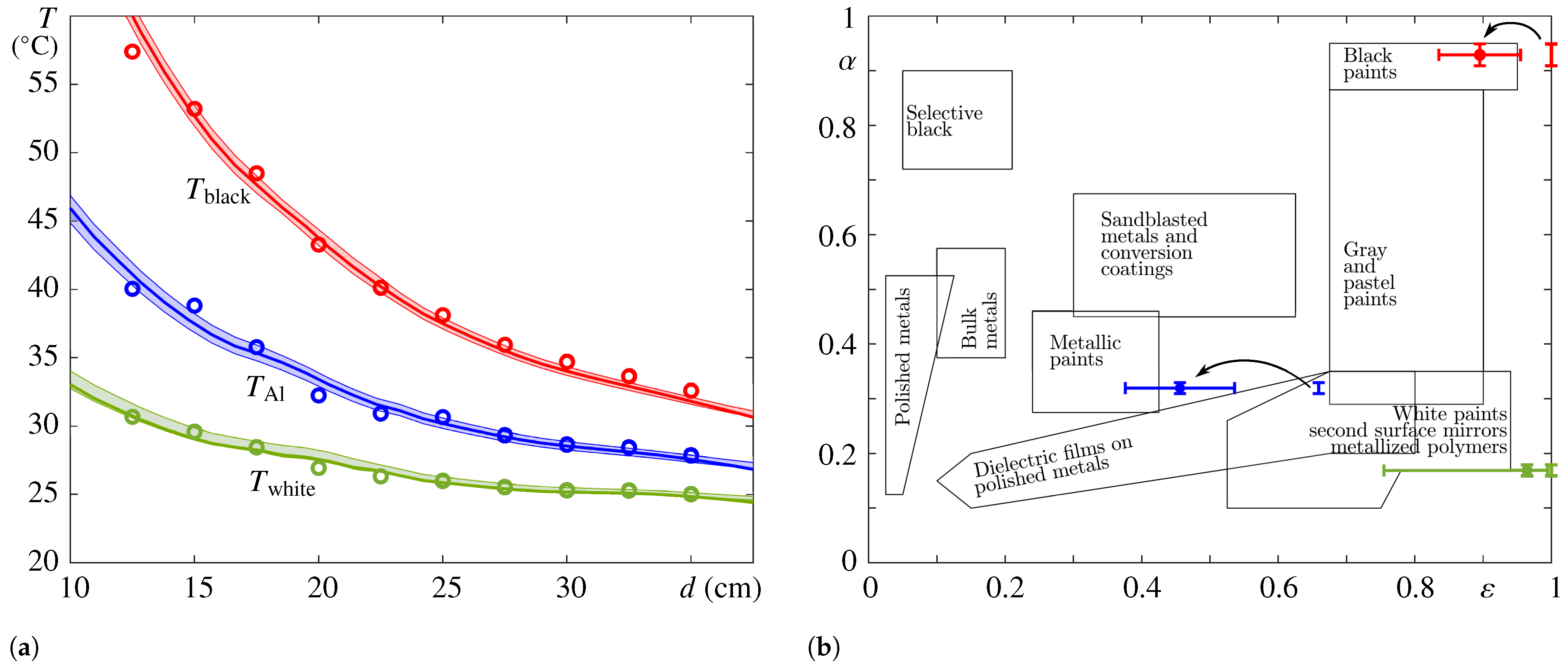

5.3. Successive Experiments at Increasing LED–Plate Distance

5.4. Data Processing and Estimate of Thermo-Optical Properties

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prince, M. Does Active Learning Work? A Review of the Research. J. Eng. Educ. 2004, 93, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Fernández, D.; Ezquerro, J.M.; Rodríguez, J.; Porter, J.; Lapuerta, V. Motivational Impact of Active Learning Methods in Aerospace Engineering Students. Acta Astronaut. 2020, 165, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diller, T.; Bairaktarova, D. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Individual Hands-on Workshops in Heat Transfer Classes to Specific Student Learning Outcomes. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2024, 40, 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, R.; Friedrich, M.; Groß, P.; Kühne, H. Hands-on keyboard: The multifunctional tutorial for teaching and practical training of space-technology at the Berlin University of Technology. Acta Astronaut. 1995, 35, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spearrin, R.M.; Bendana, F.A. Design-build-launch: A hybrid project-based laboratory course for aerospace engineering education. Acta Astronaut. 2019, 157, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.; Laverón-Simavilla, A.; del Cura, J.M.; Ezquerro, J.M.; Lapuerta, V.; Cordero-Gracia, M. Project based learning experiences in the space engineering education at Technical University of Madrid. Adv. Space Res. 2015, 56, 1319–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders-Smits, G.N.; de Graaff, E. The development of integrated professional skills in aerospace, through problem-based learning in design projects. In Proceedings of the 2003 American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference & Exposition, Nashville, TN, USA, 22–25 June 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kuswadi, S.; Nuh, M. Effective Intelligent Control Teaching Environment Using Challenge Based Learning. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Symposium on Electronics and Smart Devices (ISESD), Bandung, Indonesia, 29–30 November 2016; pp. 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, M.; Crusat, X. Work in progress: The innovation journey: A challenge-based learning methodology that introduces innovation and entrepreneurship in engineering through competition and real-life challenges. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Athens, Greece, 26–28 April 2017; pp. 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Maya, M.; Garcia, M.; Britton, E.; Acuna, A. Play lab: Creating social value through competency and challenge-based learning. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education, Oslo, Norway, 7–8 September 2017; pp. 710–715. [Google Scholar]

- Membrillo-Hernandez, J.; de Ramírez-Cadena, M.J.; Caballero-Valdes, C.; Ganem-Corvera, R.; Bustamante-Bello, R.; Benjamin-Ordoñez, J.A.; Elizalde-Siller, H. Challenge-based learning: The case of sustainable development engineering at the Tecnológico de Monterrey, Mexico City campus. Int. J. Eng. Pedagogy IJEP 2017, 8, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Mendoza, R.; Cruz-Matus, L.; Vazquez-Lepe, E.; Rios, H.; Cabeza-Azpiazu, L.; Siller, H.; Ahuett-Garza, H.; Orta-Castañon, P. Towards a disruptive active learning engineering education. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain, 18–20 April 2018; pp. 1251–1258. [Google Scholar]

- Félix-Herran, L.C.; Rendon-Nava, A.E.; Nieto-Jalil, J.M. Challenge based learning: An I semester for experiential learning in Mechatronics Engineering. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2019, 13, 1367–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessels, I.; Rueb, J.; Gess, C.; Deicke, W.; Ziegler, M. Is research-based learning effective? Evidence from a pre–post analysis in the social sciences. Stud. High. Educ. 2021, 46, 2595–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maktoumi, A.; Al-Ismaily, S.; Kacimov, A. Research-based learning for undergraduate students in soil and water sciences: A case study of hydropedology in an arid-zone environment. Int. J. Educ. Lit. Stud. 2016, 10, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguez, J.; Neri, L. Research-based learning: A case study for engineering students. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2019, 13, 1283–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawley, E.F.; Malmqvist, J.; Östlund, S. Rethinking Engineering Education: The CDIO Approach, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Crawley, E.F.; Niewoehner, R.J.; Koster, J.N. North American Aerospace Project: CDIO in Aerospace Engineering Education. In Proceedings of the 48th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting, Including the New Horizons Forum and Aerospace Exposition, Orlando, FL, USA, 4–7 January 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, J.E.; Treagust, D.F. Engineering education—Is problem-based or project-based learning the answer? Australas. J. Eng. Educ. 2003, 3, 2–16. [Google Scholar]

- Salgado Sánchez, P.; López-Fernández, D.; Fernández, J.; Ezquerro, J.; Rodríguez, J.; Del Cura, J.; Lapuerta, V. Challenge-based learning and concurrent engineering in aerospace engineering education. In Proceedings of the 15th International Technology, Education and Development Conference, Valencia, Spain, 8–10 March 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tomita, N.; Aizawa, H.; Sugie, T.; Nagamoto, Y.; Yamamoto, K. Hands-on education system using water rocket. Acta Astronaut. 2007, 61, 1072–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaram, S.; Hansen, G.; Keller, F.; Vervaecke, R.J. Project-based introduction to aerospace engineering course: A model rocket. Acta Astronaut. 2010, 66, 1526–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piattoni, J.; Magrin, L.; Majo, F.D.; Folta, D.; Zich, R.; Ciani, M. Plastic CubeSat: An innovative and low-cost way to perform applied space research and hands-on education. Acta Astronaut. 2012, 81, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E-USOC, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. Theia Space—Educational Nanosatellite Initiative. 2025. Available online: https://www.theia.eusoc.upm.es/ (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Salgado Sanchez, P.; Tinao, I.; Ezquerro, J.M.; Fernandez, J.; Rodriguez, J.; Bello, A.; Olfe, K. Educational nanosatellites for hands-on learning in aerospace engineering education. In Proceedings of the 15th International Technology, Education and Development Conference, Valencia, Spain, 8–10 March 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, U.; Bravo, L.; Gligor, D.; Olfe, K.; Bello, A.; Ezquerro, J.M.; Rodriguez, J.; Salgado Sanchez, P. Attitude Control Research with Educational Nanosatellites. In Proceedings of the 4th Symposium on Space Educational Activities, Barcelona, Spain, 27–29 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Olfe, K.S. ESAT Three-Axis ADCS Implementation. In Proceedings of the 15th PEGASUS Student Conference, Glasgow, UK, 10–12 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, A.; Olfe, K.S.; Rodriguez, J.; Ezquerro, J.M.; Lapuerta, V. Experimental Verification and Comparison of Fuzzy and PID Controllers for Attitude Control of Nanosatellites. Adv. Space Res. 2023, 71, 3613–3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezquerro, J.M.; Bello, A.; Salgado Sánchez, P.; Laverón-Simavilla, A.; Lapuerta, V. The Thermocapillary Effects in Phase Change Materials in Microgravity experiment: Design, preparation and execution of a parabolic flight experiment. Acta Astronaut. 2019, 162, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezquerro, J.M.; Salgado Sánchez, P.; Bello, A.; Rodríguez, J.; Lapuerta, V.; Laverón-Simavilla, A. Experimental evidence of thermocapillarity in phase change materials in microgravity: Measuring the effect of Marangoni convection in solid/liquid phase transitions. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 113, 104529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado Sanchez, P.; Ezquerro, J.M.; Gligor, D.; Martinez, U.; Fernandez, J.; Tinao, I. The “Effect of Marangoni convection on heat transfer in Phase Change Materials” experiment, from a student project to the International Space Station. In Proceedings of the 4th Symposium on Space Education Activities, Barcelona, Spain, 27–29 April 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, J.; Laverón-Simavilla, A.; Bou-Ali, M.; Ruiz, X.; Gavalda, F.; Ezquerro, J.; Salgado Sánchez, P.; Martínez, U.; Gligor, D.; Tinao, I.; et al. The “Effect of Marangoni Convection on Heat Transfer in Phase Change Materials” experiment. Acta Astronaut. 2023, 210, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado Sanchez, P.; Ezquerro, J.M.; Porter, J.; Fernandez, J.; Rodriguez, J.; Tinao, I.; Lapuerta, V.; Laveron-Simavilla, A.; Ruiz, X.; Gavalda, F.; et al. The effect of thermocapillary convection on PCM melting in microgravity: Results and expectations. In Proceedings of the 72nd International Astronautical Conference (IAC), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 25–29 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Salgado Sanchez, P.; Ezquerro, J.M.; Fernandez, J.; Rodriguez, J. Thermocapillary effects during the melting of phase change materials in microgravity: Heat transport enhancement. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 163, 120478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado Sanchez, P.; Ezquerro, J.M.; Fernandez, J.; Rodriguez, J. Thermocapillary effects during the melting of Phase Change Materials in microgravity: Steady and oscillatory flow regimes. J. Fluid Mech. 2021, 908, A20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varas, R.; Salgado Sánchez, P.; Porter, J.; Ezquerro, J.; Lapuerta, V. Thermocapillary effects during the melting in microgravity of phase change materials with a liquid bridge geometry. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2021, 178, 121586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borshchak Kachalov, A.; Salgado Sánchez, P.; Martínez, U.; Ezquerro, J.M. Preliminary Design of a Space Habitat Thermally Controlled Using Phase Change Materials. Thermo 2023, 3, 232–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borshchak Kachalov, A.; Salgado Sánchez, P.; Mollah, M.T.; Ezquerro, J.M.; Spangenberg, J.; Seta, B. Numerical Analysis of Coaxially 3D Printed Lunar Habitats: Integrating Regolith and PCM for Passive Temperature Control. Microgravity Sci. Technol. 2025, 37, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongil, C.; Martínez, U.; Salgado Sánchez, P.; Borshchak Kachalov, A.; Ezquerro, J.M.; Olfe, K. Laboratory Experiments on Passive Thermal Control of Space Habitats Using Phase-Change Materials. Thermo 2024, 4, 461–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S.; Eddy, S.L.; McDonough, M.; Smith, M.K.; Okoroafor, N.; Jordt, H.; Wenderoth, M.P. Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 8410–8415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakasuka, S.; Sako, N.; Sahara, H.; Nakamura, Y.; Eishima, T.; Komatsu, M. Evolution from Education to Practical Use in University of Tokyo’s Nano-Satellite Activities. Acta Astronaut. 2010, 66, 1099–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayorova, V. Integration of Educational and Scientific–Technological Areas During the Process of Education of Aerospace Engineers. Acta Astronaut. 2011, 69, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Fernández, D.; Raya, L.; Ortega, F.; Garcia, J.J. Project Based Learning Meets Service Learning on Software Development Education. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2019, 35, 1436–1445. [Google Scholar]

- Pico Technology. Pico TC-08 USB Thermocouple Data Logger. 2025. Available online: https://www.picotech.com/data-logger/tc-08/thermocouple-data-logger (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- IEC62471; Photobiological Safety of Lamps and Lamp Systems—Part 7: Light Sources and Luminaires Primarily Emitting Visible Radiation. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- E408; Standard Test Methods for Total Normal Emittance of Surfaces Using Inspection-Meter Techniques. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- E903; Standard Test Method for Solar Absorptance, Reflectance, and Transmittance of Materials Using Integrating Spheres. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- Incropera, F.P.; DeWitt, D.P.; Bergman, T.L.; Lavine, A.S. Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer, 6th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gnielinski, V. New equations for heat and mass transfer in turbulent pipe and channel flow. Int. Chem. Eng. 1976, 16, 359–368. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, R.C.; Wood, D.H.; Pahlevani, M. An experimental and numerical study of forced convection heat transfer from rectangular fins at low Reynolds numbers. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 163, 120418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traceable by Cole-Parmer. Dual-Display Traceable Light Meter. Available online: https://www.traceable.com/3252-traceable-dual-display-light-meter.html (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Berman, S.S. Energy efficiency consequences of scotopic sensitivity. J. Illum. Eng. Soc. 1990, 19, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Internationale de l’Éclairage (CIE). The Basis of Physical Photometry; Number 084-1989 in CIE Publication; CIE: Vienna, Austria, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, S.W.; Chu, H.H.S. Correlating equations for laminar and turbulent free convection from a vertical plate. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1975, 18, 1323–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachikawa, S.; Nagano, H.; Ohnishi, A.; Nagasaka, Y. Advanced Passive Thermal Control Materials and Devices for Spacecraft: A Review. Int. J. Thermophys. 2022, 43, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henninger, J. Solar Absorptance and Thermal Emittance of Some Common Spacecraft Thermal Control Coatings; Technical Report NASA-RP-1121; National Aeronautics and Space Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Liles, K.; Amundsen, R. NASA Passive Thermal Control Engineering Guidebook; Technical Report; National Aeronautics and Space Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, J.P.M. Radiation in the coffee cup. Phys. Educ. 2024, 60, 015011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberlercher, H.; Kreiter, C.; Krumphals, I.; Gloessl, A.; Berndt, A.; Straeußnigg, E.; Seriano, C.V.; Klinger, T. Remote-Controlled Laboratory for Thermal Radiation Investigations with Technical and Didactic Innovations. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), London, UK, 22–25 April 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

| Distance | cm | 12.5 | 15 | 17.5 | 20 | 22.5 | 25 | 27.5 | 30 | 32.5 | 35 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black, | °C | 57.4 | 53.2 | 48.5 | 43.3 | 40.1 | 38.1 | 35.9 | 34.7 | 33.6 | 32.6 |

| Error | °C | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| Metal, | °C | 40.0 | 38.8 | 35.8 | 32.3 | 30.9 | 30.7 | 29.3 | 28.6 | 28.4 | 27.9 |

| Error | °C | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| White, | °C | 30.7 | 29.6 | 28.4 | 26.9 | 26.3 | 26.0 | 25.5 | 25.3 | 25.3 | 25.0 |

| Error | °C | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| Air black | °C | 24.3 | 25.0 | 25.1 | 24.5 | 24.3 | 24.6 | 24.3 | 24.3 | 24.4 | 24.3 |

| Error | °C | 0.23 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| Air aluminum, | °C | 24.5 | 25.2 | 25.3 | 24.8 | 24.5 | 24.8 | 24.5 | 24.6 | 24.8 | 24.7 |

| Error | °C | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| Air white, | °C | 24.0 | 24.7 | 24.9 | 24.2 | 24.2 | 24.3 | 24.1 | 24.0 | 24.0 | 23.9 |

| Error | °C | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| Lab, | °C | 22.5 | 22.4 | 22.5 | 24.9 | 22.6 | 22.7 | 22.6 | 22.7 | 23.1 | 23.0 |

| Error | °C | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.13 |

| Black | Aluminum | White | |

|---|---|---|---|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salgado Sánchez, P.; Lebrón, A.R.; Borshchak Kachalov, A.; Oviedo, Á.; Porter, J.; Laverón Simavilla, A. A Laboratory Set-Up for Hands-On Learning of Heat Transfer Principles in Aerospace Engineering Education. Thermo 2025, 5, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/thermo5040045

Salgado Sánchez P, Lebrón AR, Borshchak Kachalov A, Oviedo Á, Porter J, Laverón Simavilla A. A Laboratory Set-Up for Hands-On Learning of Heat Transfer Principles in Aerospace Engineering Education. Thermo. 2025; 5(4):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/thermo5040045

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalgado Sánchez, Pablo, Antonio Rosado Lebrón, Andriy Borshchak Kachalov, Álvaro Oviedo, Jeff Porter, and Ana Laverón Simavilla. 2025. "A Laboratory Set-Up for Hands-On Learning of Heat Transfer Principles in Aerospace Engineering Education" Thermo 5, no. 4: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/thermo5040045

APA StyleSalgado Sánchez, P., Lebrón, A. R., Borshchak Kachalov, A., Oviedo, Á., Porter, J., & Laverón Simavilla, A. (2025). A Laboratory Set-Up for Hands-On Learning of Heat Transfer Principles in Aerospace Engineering Education. Thermo, 5(4), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/thermo5040045