1. Introduction

Conservation of any animal depends upon an understanding of the biology of that species and the threats that human society poses to that species, whether those be habitat loss, overharvest, disruption of the food chain, or climate change. The American black bear (

Ursus americanus) is present in large numbers in many areas of North America [

1] and is spreading into new areas. Simultaneously, people have expanded their urbanized footprint into bear habitats, and negative interactions between bears and humans have increased, often to the detriment of bears [

2]. This has led to demands for the elimination of bears from portions of their range. There is a need to better understand the behavior of black bears and their ability to communicate to help reduce these negative interactions and calls for elimination.

Bears have long been a source of fear in human society [

3]. People today are afraid of bears because of a long history of negative stories and stereotypes that portray bears as dangerous killers [

4,

5,

6]. In addition, people are unable to interact peacefully with bears because they do not know how bears communicate. It is much like meeting a person in a faraway country who speaks another language. Without communication, interactions can quickly escalate into misunderstandings and then violent confrontations. Many actions of humans, such as putting out food in the form of bird feeders, unsecured garbage, and unprotected chicken coops, act as attractants to bears. Such behavior leads to conflicts since people are unaware that they are inviting bears onto their properties. With over 600,000 bears in North America [

7], it is critical that people learn how bears communicate to avoid sending an “open invitation” to bears searching for anthropogenic food sources [

8,

9]. A better understanding of bear communication will improve conservation efforts.

Our understanding of the social system of bears, and the corresponding communication that supports that social system, has developed slowly in the literature. Based on their solitary habits, Lorenz [

10], Krott [

11], and Ewer [

12] suggested that bears did not have consistent social communication. While Rausch [

13] and Jonkel [

14] considered bears solitary, they recognized that bears were social during the breeding season and that females with cubs were a social unit. Stonorov and Stokes [

15] documented the social behavior and communication of Alaskan brown bears (

Ursus arctos) at concentrated food sources. Pruitt [

16] recognized that when young captive black bears were social, communication was frequent and necessary. She documented communication associated with play and aggression, and Jordon [

17] documented threat behavior and communication in a single pair of captive black bears. Stonorov and Stokes [

15] and Egbert and Stokes [

18] documented social behavior and communication in Alaskan brown bears congregating at salmon rivers. Herrero [

19] documented the social behavior and communication of black bears at a garbage dump. Stringham [

20] presented ethograms of body language and the motivations of brown bears. In our study, we clarified the communication behavior of black bears within the context of their natural behaviors and social interactions. While past studies were of limited duration and relied on limited observations, we were able to perform a longitudinal study that allowed us to further describe the forms of communication in bears.

Kilham and Spotila [

21] documented that the American black bear has a social structure based on a matrilineal hierarchy, thereby implying that black bears must have a system of communication to maintain that hierarchy. Penteriani et al. [

22,

23,

24] recently quantified brown bear marking behavior on trees and visual signaling with body color patches, indicating that they exhibit social communication. Knowledge of the system of communication of black bears will allow people to interact with these animals in a more rational manner and defuse many bear–human conflicts, resulting in an improved appreciation of and coexistence with bears and leading to improved bear conservation.

The objective of this study was to quantify the vocal and non-vocal behaviors of black bears and describe their communication system. This was a descriptive study that relied on detailed behavioral observations carried out in the field. We carried out this study in three phases, in which we observed bears and recorded their behaviors under natural conditions for a period of 24 years.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study area was 132 km

2 of northern hardwood forest comprising red oak (

Quercus rubra), beech (

Fagus grandifolia), sugar maple (

Acer saccharum), red maple (

Acer rubrum), white ash (

Fraxinus americana), white birch (

Betula papyrifera), and yellow birch (

Betula alleghanienses), with patches of softwoods, including red spruce (

Picea rubens), eastern white pine (

Pinus strobus), hemlock (

Tsuga canadensis), and balsam fir (

Abies balsamea). It was located in west central New Hampshire in the eastern and western halves of the Lyme and Dorchester townships, respectively. Smarts Mountain, at 987 m above sea level, is the highest peak and is surrounded by several smaller hills and ridges. There were four major ponds and numerous wetlands in the study area that provided fruit from various shrubs, including blueberry (

Vaccinium spp.), huckleberry (

Vaccinium spp.), mountain holly (

Ilex montana), winterberry (

Ilex verticillata), nannyberry (

Viburnum lentago), and dogwood (

Cornus spp.). Logging throughout the area created early successional habitats containing raspberries (

Rubus spp.) and blackberries (

Rubus spp.), and the decaying wood and sunlight increased the production of ants (Formicidae), wasps (Vespidae), and grubs (Coleoptera). Acorns, beech nuts, fruit from shrubs, and larvae from ants and other insects provided food for bears [

25].

In addition to black bears, other common mammals in the area included white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), moose (Alces alces), bobcats (Lynx rufus), coyotes (Canis latrans), raccoons (Procyon lotor), eastern gray squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis), snowshoe hares (Lepus americanus), red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), gray foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus), porcupines (Erethizon dorsatum), fishers (Pekania pennanti), chipmunks (Tamias striatus), and white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus). Some of these animals (deer, chipmunks, mice, and squirrels) eat the same food as black bears, i.e., acorns and berries, but do not affect the availability of that food for bears. Moose eat vegetation and do not compete with bears. A bobcat or coyote could theoretically prey on a lone bear cub, but we have not seen any data to suggest that this happens. Raccoons, foxes, porcupines, and fishers do not compete with bears.

2.2. Methods

This research took place over a 24-year period, during which the senior author (B. K.) carried out the study in three phases.

2.2.1. Phase One

In the first phase (1998–2007), B. K. spent 750 h walking with and observing black bear cubs from three litters that he raised from infancy. Bear cubs were brought to B. K. by the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department (NHFGD) to receive care and rehabilitation for subsequent return to the wild. The bears were very young, orphaned at ages ranging from 7–12 weeks, when still in their natal dens, so they had no experience with their biological mothers outside the winter den. Cubs were bottle-fed until they were able to eat natural foods and live in a natural enclosure (2 ha). Then, B. K. documented the behavior of the cubs, both in the natural enclosure and while walking them untethered in the forest several times a week. This was done to give cubs experience in a natural environment and expose them to the scent and signs of wild bears [

8,

9]. Bear cubs followed B. K., climbed on stumps and logs, chased each other, and wrestled in the leaves. They stayed near B. K. and mouthed vegetation while exploring the forest. He made observations on the free-ranging cubs in the rehabilitation program, documenting their first reactions to their natural environment and their olfactory behavior, vocalizations, marking behavior, foraging behavior, interactions with the other bear cubs and other animals, responses to their own scent, and responses to the scent of wild bears. Additionally, he spent over 1000 h walking with two wild female bears, from yearlings to adulthood. He documented his observations with field notes in waterproof notebooks, photographs, and videos. All rehabilitated bears were released into the wild at approximately 18 months of age, and most were not part of later studies. Behaviors documented by rehabilitated bears under natural conditions during the first component of the study were prepared by B. K. in order to carry out the second and third phases of this study. His observations were validated by video recordings of the bears’ behavior and by two independent observers.

2.2.2. Phase Two

In the second phase (1998–2015), B. K. spent 800+ h observing the behavior of radio-collared bears. In 1998, he fitted a rehabilitated bear, SQ, with an adjustable VHF collar that could be taken on and off without sedating the bear [

8,

9]. Because SQ was habituated to his presence, B. K. was able to observe her behavior at close range in natural habitats for up to five hours at a time, including intraspecific social interactions, foraging, scent marking, and tracking of other bears. As a part of a cooperative study with the NHFGD, B. K. also tracked 40 wild female bears over a 24-year period with telemetry and GPS tracking collars (Telemetry Solutions, Lotek 7000 ms and Lotek M, and Vectronic Aerospace Vertex Lite-Iridium). He observed social interactions with other bears but could not always identify the wild bears. He would provide the bears with a small food reward, then walk with them as they foraged, scent-marked, and tracked other bears. There were no reports of the bears in the study becoming dependent on human food. He documented his observations with field notes, photographs, and videos. Data were written in pencil in waterproof field notebooks, and later in an Apple iPad, before being transferred to a desktop computer. Rogers and Wilker [

26], DeBruyn [

27], Stringham [

28], and Fredriksson [

29] used similar methods in their studies, in which they observed bears in the wild and recorded their behavior. Kilham’s observations were validated by video recordings of the bears’ behavior and by two independent observers.

2.2.3. Phase Three

The third phase of the study was centered on an observation site. Here, B. K. observed and documented social interactions among wild bears from 2007–2021. He spent 1.5 h per day for 3600 days observing wild bears interacting at the observation site. There were 1 to 12 bears at the site at any given time. He had access to wild bears during the second and third phases of the study because these bears accepted his presence and appeared to act naturally during observation periods. Bears acted the same as when he encountered wild bears in the forest. Kilham took advantage of the habituation of the bears to his presence to observe their behavior. He followed the approach of participant observation commonly used in animal behavior field studies since the classic research of Goodall [

30] and Schaller [

31]. Bejder et al. [

32] reviewed the use and misuse of habituation in describing wildlife responses to anthropogenic stimuli.

Kilham chose direct observations of bears over the use of game/field cameras in order to observe the behavior and interactions of bears in real time and to observe many behaviors over a wider field of view, which would not be recorded by still or video cameras in fixed locations. B. K. documented his observations using field notes in waterproof notebooks, photographs, and videos. Later, he recorded data on an iPad. Data were transferred to a desktop computer. The identity of each bear was recorded, and the bear that was the signaler was noted, as was the bear that was the recipient of the signal. The time and duration of the action were also recorded, along with the length of the observation periods. His observations were validated by video recordings of the behavior of the bears and by seven independent observers, including the co-authors of this paper.

The observation site was on private property, approximately 2 km from the nearest road and 1 km from the nearest human residence. Bears were provided with corn (approximately 1.5 kg/bear) in 5–10 individual piles, spaced 5–60 m apart and located 3–40 m from the observation vehicle. Any bear that visited the site had access to corn. Food was distributed in a manner to minimize competition and conflict over food. Bears fed on different piles of corn, and there were usually unused piles available. B. K. made observations most evenings from 1 April–30 November for periods averaging 1.5 h. The duration of observation was recorded each day, along with data on the identity of the bear, its action, and the time of the behavior. Observation areas and other concentrated food sources (such as salmon rivers or garbage dumps for bears) have been used for behavioral studies on bears [

19,

33], dolphins [

34], and chimpanzees [

35,

36]. While the feeding of bears by the general public is generally illegal in most states in the United States, it was approved for this study under a scientific permit issued by the NHFGD because of the valuable data that could be collected on bear behavior.

Bears were identified using distinguishing features and characteristics, including facial markings, head and body shape, body length, color patterns on muzzles, behaviors, scars, tears in ears, white chest patches, ear tags, limps, and radio collars [

15,

19,

24]. Pedigree was determined using personal knowledge of cubs and mothers from birth and microsatellite DNA using eleven polymorphic markers [

21]. The personal knowledge and genetic analysis provided a consistent pedigree.

2.3. Classification of Behaviors

Bears communicated with vocalizations, olfactory behavior, marking behavior, body language, and emotional expressions. We used the term “automatic communication” to mean “communication done without conscious thought or volition, as if mechanically or from reflex”. It involved zero-order intentionality, i.e., a signal produced as a reaction to a stimulus with no intention of communicating a goal. It was clear to the observer that there was no goal, and the communication did not involve first-order intentionality. We defined “intentional communication” to mean “the action was done on purpose with an aim in mind”. That is, the action was goal-directed and involved first-order intentionality. It involved signals produced with the intention of communicating a cognitive goal that modifies a recipient’s behavior. The bear performed audience checking to see the recipient’s state of visual attention, response waiting by pausing and waiting for a response, and goal persistence, in which she continued to signal or intensified her signals when the recipient did not respond. These classifications follow Dennett [

36] and Eleuteri et al. [

37]. We are limited in our ability to “prove” that communication behavior was automatic or intentional because this study was descriptive and did not test pre-established hypotheses/predictions. Our observations led us to interpret the behaviors as appearing to be automatic or intentional. Our data provide a basis for future experimental studies that can test hypotheses in wild bears.

2.4. Bear Capture and Handling

In Phase Two of this study, wild bears were captured using barrel traps (0.6 × 1.8 m) baited with dry corn to be used in the telemetry study. All trapping efforts occurred after obtaining written landowner permission. Under the guidance of our veterinarian, we sedated bears using ketamine/xylazine (ketamine 4–16 mg/kg + xylazine 2–8 mg/kg (ket: 200 mg/mL; xyl: 100 mg/mL)) [

38,

39] with a jab stick. Then, a telemetry collar was placed around the neck. Collar maintenance was performed during winter den checks in conjunction with the NHFGD, where bears were immobilized with Telazol (6 mg/kg) administered with a jab stick. All vital rates, including heart and respiration rates, pulse, capillary refill time, and rectal temperature, were monitored during immobilization. Bears were tagged with numbered stainless steel ear tags (National Band and Tag company).

2.5. Permits and Animal Care

The NHFGD provided Scientific Research and Rehabilitation permits each year, as well as the cubs for research, rehabilitation, and release into the wild. Permits covered all aspects of this study over the entire study period and were renewed annually. All handling of animals was conducted within the guidelines of handling research animals of the American Society of Mammalogists [

40] and was approved by the NHFGD.

3. Results

Bears communicated with vocalizations, olfactory behavior, marking behavior, body language, and emotional expressions. During the study, B. K. made several serendipitous observations of bear behavior that provided additional data on communication. The behaviors reported in this paper were observed many times during an observation season, with some observed almost every day. In order to provide quantitative context to our observations, we sampled the data for 2008–2014 and provided the figures of these observations in the results.

3.1. Vocalizations

There were 13 types of vocalizations documented, ranging from a soft chirp to a roar (

Table 1). The chirp was a soft “uh” sound made by the male to his mate or the female to her cubs. A “num, num, num” sound was made by a cub when it did not want to share food with another cub. A “gulp” was generated in the throat and used with body language by females to manage and direct cubs (

Video S1) and by males around females during mating season. The other vocalizations all had their own contexts.

During the period from 2008 to 2014, B. K. recorded the gulp vocalization 130 times; the gulp with chirp six times; the gulp with false charge six times; the gulp calling cubs down from trees 21 times; huff and huffing190 times; huh, huh, huh 23 times; num, num, num six times; mew mew 23 times; mm, mm, mm two times; roar 23 times; humming one time; a chirp 31 times; an undulating moan 25 times; and a moan of recognition 63 times.

There were also non-vocal open-mouth behaviors. A “yawn” occurred when the bear was relaxed and tired, and the tongue often extended out and curled (nine times in 2008–2014). A “nervous yawn” was when the bear lowered its head and dropped the lower jaw to open the mouth. That occurred in tense situations, such as when another bear approached too close and expressed dominance or was a perceived threat (

Figure 1). The same occurred with the approach of an unknown human. “Jawing” occurred when two bears faced each other with open mouths in close proximity and was routinely observed. It occurred in multiple situations, including a solicitation of friendship, sharing food, cub play in stand-up wrestling, or a male and female getting acquainted during mating season (

Figure 2).

3.2. Olfactory Behavior

Olfactory behavior provided information about the environment and other bears. It was most easily observed in cubs because cubs often exaggerated behavior. It ranged from a slow lick to opening and closing the mouth while inhaling and exhaling air (

Table 2). In the slow lick, the tongue came out and stuck to an object, lifting scent with saliva and transferring it back into the mouth to the papilla of the vomeronasal organ (VNO) in the palate of the roof of the mouth. Behaviors associated with olfaction, such as audible sniffs, slow licks, and olfactory huffs, often occurred in combination (

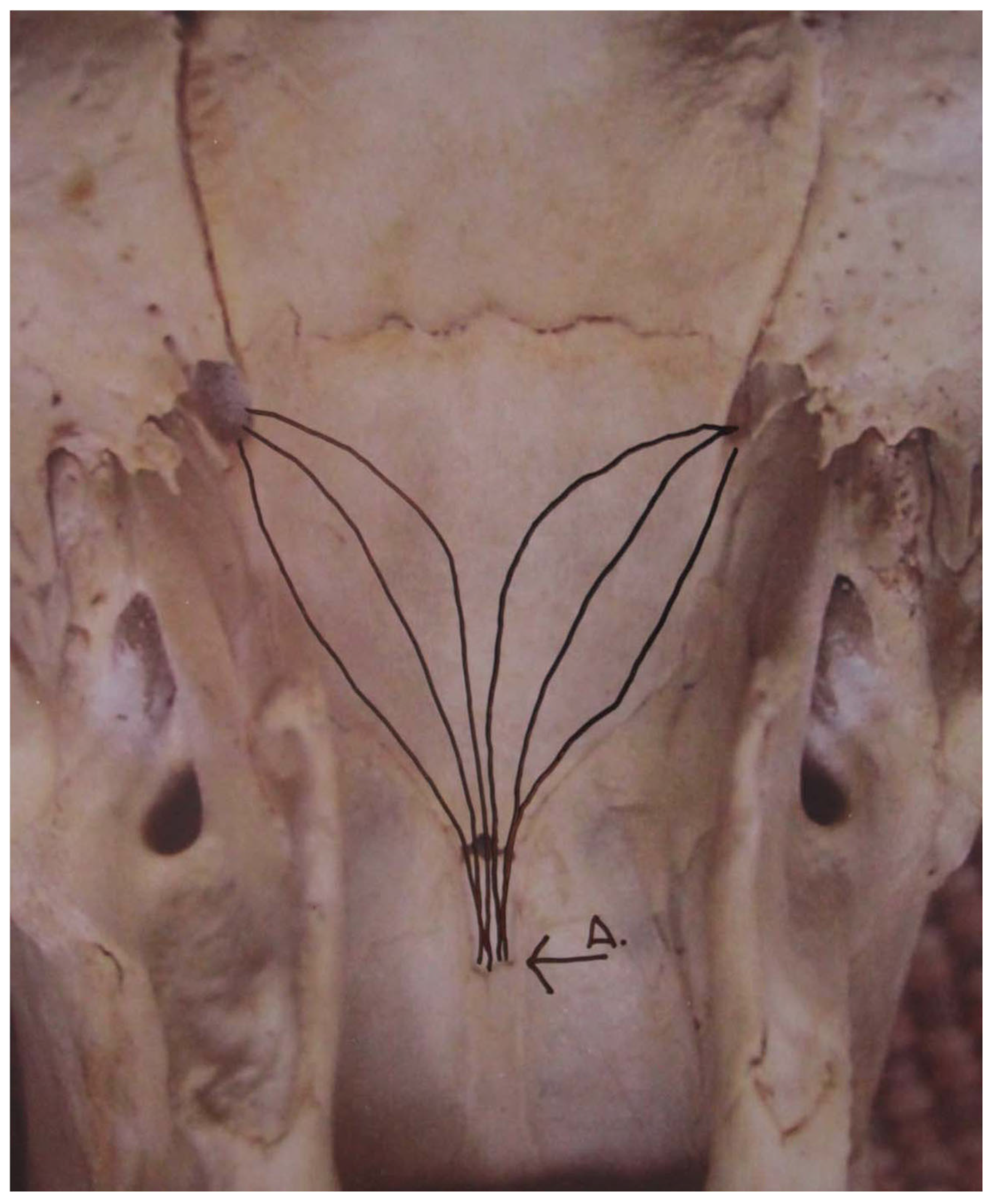

n = 453). In adult bears, the same behavior occurred but was very subtle and often hard to observe. When a bear encountered a scent in the air, it exhaled air from its mouth, closed its mouth, and drew air back into the nostrils, where the air now contained scent molecules. The aromatic molecules pass over the sensory nerves of an accessory vomeronasal organ (AVNO), which has been termed the Kilham Organ [

8] (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Bears lifted the scent from the air or vegetation (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). The open-mouth grin occurred when a male was following an estrous female (

Video S2), where the male was opening and closing its mouth, expelling moist air from its lungs such that it picked up airborne scents, monitoring the female’s condition of estrus.

3.3. Marking Behavior

Black bears intentionally marked their environment in eight different ways, ranging from a simple chin rub to a stiff-legged walk (

Table 3). A stiff-legged walk (SLW) was a visual warning to another bear or a human. It left a mark in the soil that was recognized by other bears through both visual and olfactory senses. From 2008 to 2014, B. K. recorded SLWs by adult bears 206 times. He observed SLWs with marking with urine (M/U) (

n = 18); marking with scat (M/S) (

n = 24); marking with both urine and scat (

n = 5); with walking over sapling (WOS) (

n = 69); and SLW with a false charge (

n = 9). He also observed a full back rub (FBR) (

n = 374); mark with semen (

n = 8); chin rub (

n = 36); and side rub (

n = 44). While walking cubs, he observed SLW (

n = 307); WOS (

n = 50); M/U (

n = 268); and M/S (

n = 62). Walking over a sapling (WOS), a bear deposited a scent, and when the sapling popped back up, it served as an olfactory antenna (

Video S3—sapling as an olfactory antenna). Marking with scat was differentiated from defecating as it was performed in response to a scent, in a specific location (e.g., center of a trail), in conjunction with other behaviors such as SLW, and acted to identify the bear’s presence. Scats were later smelled by other bears, obtaining information about which bear deposited the scat.

Unintentional marking also occurred during routine travel as a bear deposited its scent on anything that its fur, feet, or any part of its body touched. These marks made the bear’s movements transparent to other bears. B. K. observed other bears following scent trails that were 48+ h old. For example, when B. K. walked cubs through the forest, they would detect scents on objects by sniffing, licking, or using an olfactory huff wherever a scent was deposited on any leaf, twig, branch, or on the ground (n = 17). Cubs followed the trail left by another bear. For example, when they found a fresh apple scat left by a wild bear, they followed its trail back to the orchard where the bear had fed (n = 6).

3.4. Body Language

Black bears communicated with each other using 16 types of body language (

Table 4). These included walking toward another bear with eyes on the subject, exhibiting dominance to take away food or displace the individual, chasing and/or treeing to establish rank or run off a male, and charging and false charging. B. K. observed each of these behaviors 100+ times (

Video S4—chasing cubs up a tree, and

Video S5—false charge). He also observed additional behaviors relating to mating, for which there were limited sample sizes (

n = 29) (

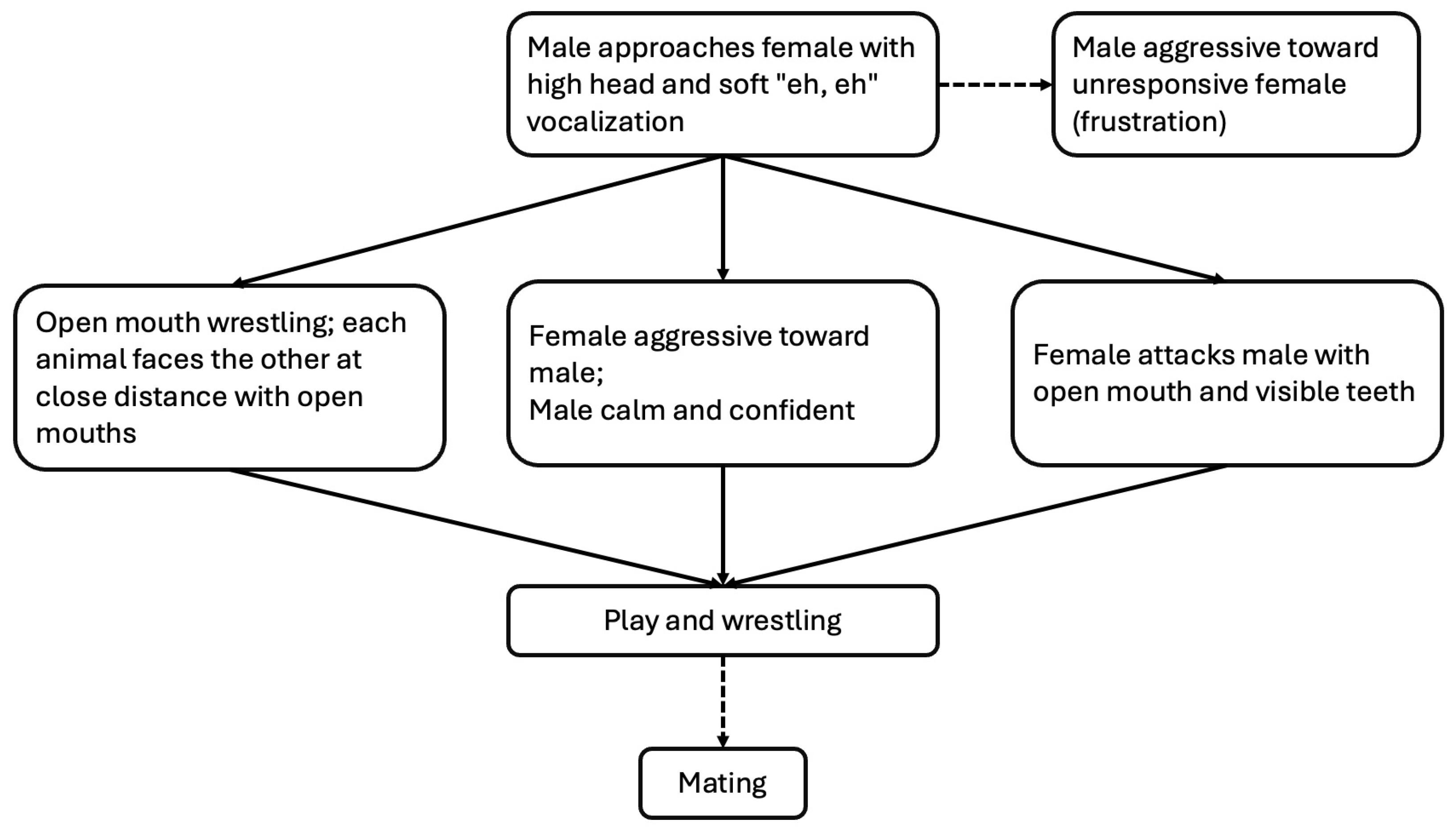

Figure 7).

Communication was the key to successful mating behavior in black bears. Mating behavior in black bears was symbolically aggressive between females and males (

Figure 7), but actually aggressive between males. Mating often involved play and wrestling. Males approached females with quiet vocalizations, and females often responded with an open mouth. While females acted aggressively towards males and wrestling occurred, there was no actual biting or harm done. Males remained calm and appeared confident. Males showed frustration if the females were unreceptive. Males used aggressive behaviors towards other males when competing for a female.

3.5. Automatic Communication

We observed that black bears showed a range of emotional communication via facial expressions, including aggravation, happiness, and solicitation (

Figure 8—aggravated face, and

Figure 9—happy face). A bear with ears pinned back showed aggression, and ears cocked forward indicated focused intention. When distressed, a bear would often generate an undulating moan. For example, a cub when treed by its mother during weaning would loudly moan. The intensity of vocalizations and actions appeared to change with the apparent emotional state of the animal. These expressions and sounds appeared to us to be automatic and appeared to involve zero-order intentionality.

3.6. Intentional Communication

Body language appeared to be a form of first-order intentional communication. In over 100 different observations, false charges signaled different meanings. Some appeared to delay confrontation until communication took place. Some appeared to be more aggressive as a threat. For example, when B. K. approached an unknown bear with cubs, the sow false-charged, circled, and examined his back trail before returning to her cubs. By remaining still and speaking softly, B. K. communicated a lack of threat and observed the group for two hours without further confrontation. False charge behavior also occurred as a request for more food, as a warning of being too close, and as a request to leave during an interaction (

Video S5). There was varied intensity to false charges, ranging from a simple bow to a highly aggressive bluff charge. In some cases, a false charge occurred as a result of approaching thunderstorms or in response to an airborne scent of an approaching bear before the bear appeared.

Several times, black bears appeared to intentionally communicate with B. K. in what appeared to be goal-directed or first-order intentionality. For example, in March of 2002, he visited a bear at her winter den; she approached him and tried to take his gloves. He thought she was just interested in them as novel play objects for her cubs. He took them away. The bear crossed 3 m of snow and started raking the few available beech leaves toward the den. Then B. K. looked in the den and saw that snow had blown in and the cubs were sitting on a bed of ice. He realized that it was bedding that she needed and gave her his fleece jacket, which she took into the den. He returned the next day with a half bale of hay, which she promptly pulled into the den. It is possible that the bear was communicating with him about her need for bedding for her den.

3.7. Additional Observations

B. K. made serendipitous observations while he had access to bears freely behaving in their natural environment. They provided insights into black bear behavior and pointed to future studies that can be done with black bears in the wild.

3.8. Deception

Bears apparently used behavior to deceive B. K. in examples of what may be first-order intentionality. For example, in 1998, bear SQ brought her cubs to him in the forest for the first time when they were 5 months old. They looked at him and panicked, running and going up the nearest tree. They continued to show their fear by chomping and making undulating moans in the treetop. In this context, SQ regarded him as a threat to her cubs. When he walked up to her, she would sit at the base of a tree and look up as she normally did, indicating that her cubs were up that tree. However, there were no cubs up that tree, and after searching, he found the cubs up a tree several hundred feet away. We interpreted that as intentional behavior.

In another example, when SQ was a sub-adult, she deceived B. K. and bit him, changing his behavior. Normally, he would approach her and call out to her. She would appear and walk directly toward him, a form of body language that was aggressive (

Table 4). She would modify her action with an appeasement vocalization (a repetitive “Mm, Mm, Mm”;

Table 1), indicating that she was not aggressive. On one occasion, she deceived him with the same modifier. SQ was having an aggressive interaction with an unknown bear up a large white pine tree. The encounter was loud and out of sight, and as B. K. approached, he broke a large stick, causing the unknown bear to jump out of the tree and run off. SQ came down and followed the other bear’s scent a short distance, then returned to B. K. She approached him directly, making the soft “Mm, Mm, Mm” of a friendly approach. When she got to him, she stood bipedally and greeted him nose-to-nose, which is how bears greet each other, then she pinned her ears back and bit him on the upper arm, leaving a bruise. He interpreted her behavior to indicate that she was disturbed because he had interfered in her interaction with the other bear. However, she modified the bite so as not to cause real injury. She then dropped to her feet and followed him, making the moan of reconciliation, which was similar to the appeasement vocalization, apparently making up for punishing him. In this case, he was deceived by her approach because her intentions were unknown. However, she then acted to repair the broken communication. He interpreted her actions to be goal-directed and that her signals indicated first-order intentionality. These observations suggest that the bears were intentionally deceiving B. K. Future studies are needed to investigate this further.

3.9. Social Learning

Black bears conditioned other bears to respond to their scent by punishment, such as chasing a bear up a tree and then marking the area with scent, indicating that scent was a signal of dominance. The information from vocal, olfactory, and physical marking behavior was used with conditioning to establish the meaning of the signals.

Female black bears conditioned their cubs to follow their instructions (a mix of gulp and chirp vocalizations (

Table 1) and body language (

Table 4)). “Gulping” while walking towards a tree would get her cubs to climb a tree. The “gulping” vocalization would rally the cubs, and walking towards the tree would show her intent. If there was imminent danger, the intensity of the “gulps” would increase, and her actions would reflect her concern. Cubs learned from these situations and began to respond to threats themselves. B. K. observed these behaviors more than 300 times.

When a female wanted her cubs to come down from a tree, she stood at the base of the tree, looking up at her cubs while making the “gulp” vocalization. The “gulp” got their attention, and her position or body language communicated her intention to have them come down. When she wanted them to follow her, she “gulped” while walking away. In each case, the vocalization got the cubs’ attention, and different body actions and intensities communicated different messages. Female bears actively conditioned their cubs on how to respond. For example, B. K. observed a female bear turning and false-charging her cubs, sending them back up a tree when they attempted to follow her away from the tree. He observed this behavior in other female bears as well (

n = 117) (

Video S4).

4. Discussion

We documented two distinct types of communication used by black bears in this study. One appeared to be an automatic response of the central nervous system and involved zero-order intentionality. The other appeared to be intentional and involved first-order or goal-directed intentionality [

36]. These were interpretations of the observed behaviors and were not based on experimental data. Automatic communication included facial expressions, ear movements, some forms of body language, and the intensity of vocalizations and various moans. Intentional communication included the chomping of teeth, huffing, swatting, false charging, and various vocalizations. Intentional communication appeared to be deliberate, including mechanically generated sounds and actions that were used to inform, deceive, or bluff, ultimately influencing the actions of the recipient. Intentional behaviors appeared to be gestures, as discussed by Grund et al. [

41] and described in African elephants (

Loxodonta africana) by Eleuteri et al. [

37] and chimpanzees (

Pan troglodytes) by Hobaiter and Byrne [

42]. The bear appeared to perform audience checking to see the recipient’s state of visual attention, response waiting by pausing and waiting for a response, and goal persistence in which she continued to signal or intensified her signals when the recipient did not respond. These behaviors appeared to be used to influence the behavior of other bears, as discussed by Rendall et al. [

43].

The problem of intentional signaling has been of interest to biologists for many years, and in 1991, Hauser and Nelson [

44] concluded that predictive signaling involves signals that accurately reveal information about subsequent behavior by the signaler and that intentional signaling implies that complex mental processes guide the behavior of the animal. It is now assumed that higher orders of intentionality involve some recognition of the signaler’s own mental state as well as that of the audience, resulting in the capacity of the actor to successfully communicate its own intentions to the audience [

45]. Criteria to measure intentional communication involve the signal being directed to particular recipients, the sensitivity of the signaler to the attentional state of the recipient, manipulation of the attention state of the recipient, monitoring the response of the recipient, and persistence in the production of the signal until the desired goal is met [

46]. All these criteria appeared to be met by the bears in our study. Bears appeared to use intentional behaviors to maintain interpersonal relationships and to intentionally communicate with other bears and humans. Bears appeared to use intentional communication to repair failed communication and for deception and social conditioning. Further research is needed to quantify those behaviors in an experimental context in natural or semi-natural environments, as was recently done for African elephants [

37].

Communication is fundamental to the maintenance of an animal population [

47]. It is hypothesized that animals living in a more complex social environment exhibit more signals and more complex signals than animals in a simpler social environment [

48]. The black bears in our study live in a complex social society under a matrilineal hierarchy [

21]. Therefore, it is not surprising that they exhibited a complex communication system. Brown bears in the Cantabrian Mountains of northwestern Spain also exhibit a sophisticated system of communication, including olfactory and visual communication focused on the debarking of focal trees and recognition of the marking patches of color that differ on individual bears [

22,

23,

24]. The literature provides several anecdotal examples of black bear and brown bear communication [

17,

19,

49,

50,

51]. Most of those observations document various forms of behavior, including false charging, chasing, and huffing. Our black bears communicated with vocal signals, olfactory signals, body language, pantomime, and ear, eye, mouth, and facial expressions. These forms of complex communication allowed the maintenance of a complex social structure [

21] that needs to be taken into account when conservation measures are developed.

Even a single observation in nature can play an important role in understanding behavior. Schaller [

52] was able to determine important aspects of the food habits of Himalayan black bears (

Selenarctos thibetanus) from a short-term study of only 17 bears. Our results demonstrate the value of the “behavioral habituation” methodology in animal behavior studies. An important component of such studies is for the researcher to partake in the life of the animals without disrupting normal behavior. B. K. was able to do this because he had access to known and unknown bears through his relationship with an individual that he had raised from an early age.

There is always a concern when a study is performed where the animals are habituated to the investigator. However, the behavioral habituation method has been shown to provide access to animal populations so that observations of behavior can be made that would otherwise be unavailable [

30,

31]. In our study, only one bear at the observation site was a rehabilitated bear, SQ. The other bears were all wild. Independent observers reported that when B. K. was present at the site, the bears did not visually react to him. When another human approached the bears, they all retreated into the forest. The behaviors observed in Phases 1 and 2 were the same as those observed in Phase 3 at the observation site. The observation site allowed for more concentrated activity among the bears and more observations of communication. It is not possible to compare the behaviors of the bears pre- and post-observation because the social interactions of the bears could not be readily observed without the observation site. The observations made from wild bears encountered in the forest were consistent with the behavior of bears at the observation site. The vocal and non-vocal behaviors of the cubs walked by B. K. in the forest were the same as those observed in the bears at the observation site. There were no ethical or conservation concerns in the use of the observation site. In fact, since many states allow hunters to use bait sites to hunt bears, it was a positive action to keep the bears near the observation site so that they did not go to bait sites. It will be interesting for future investigators to use remote sensing, AI, and more experimental approaches to further investigate the communication of bears.

Conservation Implications

Conservation assumes that any animal has the right to continue to exist based on its own self-worth. If people have a better understanding of bears, they are more likely to support conservation measures to protect bears in their natural habitats. With over 600,000 black bears in North America, more humans are living in proximity to black bears. Black bears have a myriad of ways in which they communicate with other bears and people. These complex social behaviors can be used to guide the behavioral management of black bears. Based on our data on black bear communication, human–bear conflicts can be reduced and defused through behavioral modifications on the part of people. In most cases, conflicts are not caused by “problem bears” but “problem people” who fail to manage food attractants and do not understand bear behavior. Shifting conflict mitigation measures from bears to humans may reduce bear conflict incidents [

53]. Interactions with bears can be reduced by eliminating food sources, particularly given that black bears share food sources with other bears [

21]. Bears assume that anthropogenic foods made available in residential areas are available for sharing. Eliminating or securing anthropogenic food sources (e.g., bird feeders, garbage, poultry, pet foods, etc.) represents the most efficient way to deter bears from human-occupied areas. That approach has already been used to reduce bear–human conflict in Yellowstone National Park [

54,

55] and should be part of any conservation plan.