Flowing Towards Restoration: Cissus verticillata Phytoremediation Potential for Quebrada Juan Mendez in San Juan, Puerto Rico

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site of Local Watershed

2.2. Study Species Collection and Acclimation

2.3. Phytoremediation Experiment

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Water Quality in Juan Mendez Creek (JMC)

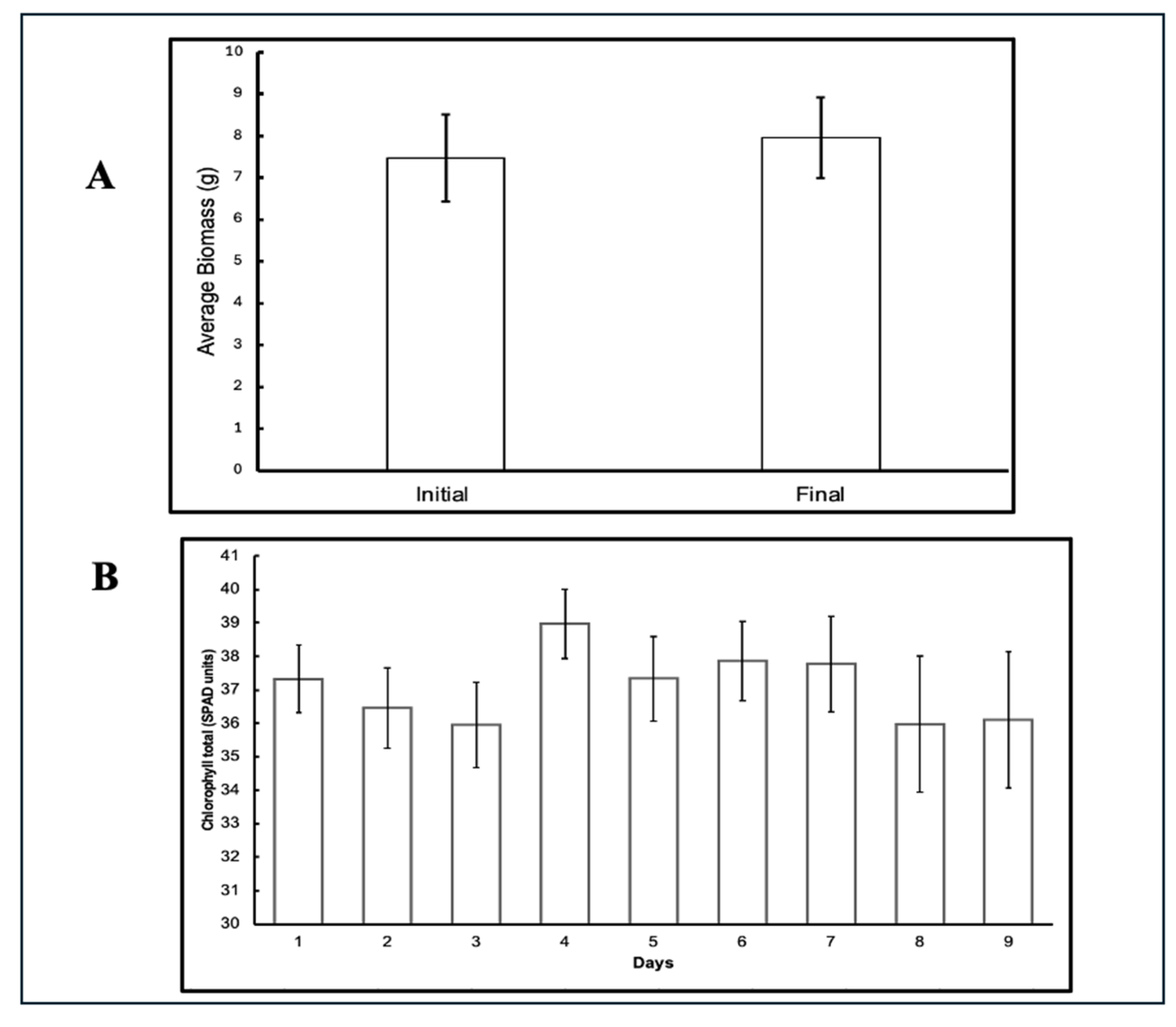

3.2. Plant Growth and Stress

3.3. Mechanisms of Translocation of Cadmium and Lead

3.4. Phytoextraction of Cadmium and Lead

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Freeman, L.A.; Corbett, D.R.; Fitzgerald, A.M.; Lemley, D.A.; Quigg, A.; Steppe, C.N. Impacts of urbanization and development on estuarine ecosystems and water quality. Estuaries Coasts 2019, 42, 1821–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Cui, E.; Sun, H. Temporal and spatial variations in the relationship between urbanization and water quality. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 13646–13655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, W.; Ni, P.; Chen, Y.; Gao, Y.; Li, S.; Zhan, A. Biological consequences of environmental pollution in running water ecosystems: A case study in zooplankton. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 1483–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GESAMP. Protecting the Oceans from Land-Based Activities: Land-Based Sources and Activities Affecting the Quality and Uses of the Marine, Coastal and Associated Freshwater Environment (GESAMP Reports and Studies No. 71); United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2001; Report No.: 71; Available online: http://www.gesamp.org/publications/protecting-the-oceans-from-land-based-activities (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Mallin, M.A.; Williams, K.E.; Esham, E.C.; Lowe, R.P. Effect of human development on bacteriological water quality in coastal watersheds. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 1047–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carle, M.V.; Halpin, P.N.; Stow, C.A. Patterns of watershed urbanization and impacts on water quality. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2005, 41, 693–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafi, S.M. Environmental Pollution; Atlantic Publishers & Distributors: New Delhi, India, 2005; Available online: https://books.google.com.pr/books?hl=en&lr=&id=bd8UxaeRFmgC&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=land+contamination+shafi+2005&ots=fbJJOahos-&sig=oYus661i9Qz8N9CDg3lxpTKtSU0&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Ali, H.; Khan, E.; Ilahi, I. Environmental chemistry and ecotoxicology of hazardous heavy metals: Environmental persistence, toxicity, and bioaccumulation. J. Chem. 2019, 2019, 6730305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidon, N.B.; Szabó, R.; Budai, P.; Lehel, J. Trophic transfer and biomagnification potential of environmental contaminants (heavy metals) in aquatic ecosystems. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 340, 122815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffries, T.C.; Schmitz Fontes, M.L.; Harrison, D.P.; Van-Dongen-Vogels, V.; Eyre, B.D.; Ralph, P.J.; Seymour, J.R. Bacterioplankton dynamics within a large anthropogenically impacted urban estuary. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 6, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quero, G.M.; Cassin, D.; Botter, M.; Perini, L.; Luna, G.M. Patterns of benthic bacterial diversity in coastal areas contaminated by heavy metals, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchounwou, P.B.; Yedjou, C.G.; Patlolla, A.K.; Sutton, D.J. Heavy metal toxicity and the environment. EXS 2012, 101, 133–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Agents Classified by the IARC Monographs; World Health Organization: Lyon, France, 2025; Volume 1–138, Available online: https://monographs.iarc.who.int/agents-classified-by-the-iarc/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Shalan, M.G.; Mostafa, M.S.; Hassouna, M.M.; El-Nabi, S.E.H.; El-Refaie, A. Amelioration of lead toxicity on rat liver with vitamin C and silymarin supplements. Toxicology 2005, 206, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.N.D.; Marion, M.; Denizeau, F.; Jumarie, C. Cadmium-induced apoptosis in rat hepatocytes does not necessarily involve caspase-dependent pathways. Toxicol. In Vitro 2006, 20, 1331–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurer-Orhan, H.; Sabır, H.U.; Özgüneş, H. Correlation between clinical indicators of lead poisoning and oxidative stress parameters in controls and lead-exposed workers. Toxicology 2004, 195, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, C.L.M.; Havstad, S.; Ownby, D.R.; Peterson, E.L.; Maliarik, M.; McCabe, M.J.; Barone, C.; Johnson, C.C. Blood lead level and risk of asthma. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 900–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caserta, D.; Graziano, A.; Lo Monte, G.; Bordi, G.; Moscarini, M. Heavy metals and placental fetal-maternal barrier: A mini-review on the major concerns. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2013, 17, 2198–2206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Saleh, I.; Shinwari, N.; Mashhour, A. Heavy metal concentrations in the breast milk of Saudi women. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2003, 96, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salt, D.E.; Smith, R.D.; Raskin, I. Phytoremediation. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 1998, 49, 643–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkorta, I.; Hernández-Allica, J.; Becerril, J.; Amezaga, I.; Albizu, I.; Garbisu, C. Recent findings on the phytoremediation of soils contaminated with environmentally toxic heavy metals and metalloids such as zinc, cadmium, lead, and arsenic. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2004, 3, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R.K.; Herat, S.; Tandon, P.K. Phytoremediation: Role of Plants in Contaminated Site Management. In Environmental Bioremediation Technologies; Singh, S.N., Tripathi, R.D., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangahu, B.V.; Abdullah, S.R.S.; Basri, H.; Idris, M.; Anuar, N.; Mukhlisin, M. A review on heavy metals (As, Pb, and Hg) uptake by plants through phytoremediation. Int. J. Chem. Eng. 2011, 939161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.B.A.N.; Dushenkov, V.; Motto, H.; Raskin, I. Phytoextraction: The use of plants to remove heavy metals from soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1995, 29, 1232–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaboudi, K.A.; Ahmed, B.; Brodie, G. Phytoremediation of Pb and Cd contaminated soils by using sunflower (Helianthus annuus) plant. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2018, 63, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, P.; Yang, Q.W.; Wang, H.B.; Shu, W.S. Phytoextraction of heavy metals by eight plant species in the field. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2007, 184, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Introduction to Phytoremediation; National Risk Management Research Laboratory: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2000; Report No.: EPA/600/R-99/107. Available online: http://www.clu-in.org/download/remed/introphyto.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Futughe, A.E.; Purchase, D.; Jones, H. Phytoremediation using native plants. In Phytoremediation; Shmaefsky, B., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, E.J.; Cánovas, M.; Gálvez, M.E.; Montofré, Í.L.; Keith, B.F.; Faz, Á. Evaluation of the phytoremediation potential of native plants growing on a copper mine tailing in northern Chile. J. Geochem. Explor. 2017, 182 (Pt B), 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi Kouhi, S.M.; Moudi, M. Assessment of phytoremediation potential of native plant species naturally growing in a heavy metal-polluted saline–sodic soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 10027–10038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, M.J.; Pignata, M.L. Lead accumulation in plants grown in polluted soils: Screening of native species for phytoremediation. J. Geochem. Explor. 2014, 137, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keellings, D.; Hernández Ayala, J.J. Extreme rainfall associated with Hurricane Maria over Puerto Rico and its connections to climate variability and change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 2964–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmaier, K.; Burlando, P.; Perona, P. Mechanisms of vegetation uprooting by flow in alluvial non-cohesive sediment. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2011, 15, 1615–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penfound, W.T. The role of vines in plant communities. Adv. Front. Plant Sci. 1966, 17, 187–192. [Google Scholar]

- Gökbayrak, Z.; Dardeniz, A.; Arıkan, A.; Kaplan, U. Best duration for submersion of grapevine cuttings of rootstock 41B in water to increase root formation. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2010, 8, 607–609. [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo-Rodríguez, P. Vines and climbing plants of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. In Contributions from the United States National Herbarium; Smithsonian Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; Volume 51, pp. 396–401. [Google Scholar]

- Hummes, A.P.; Bortoluzzi, E.C.; Tonini, V.; da Silva, L.P.; Petry, C. Transfer of copper and zinc from soil to grapevine-derived products in young and centenarian vineyards. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2019, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Juan Bay Estuary Partnership. Juan Mendez Creek Restoration Project; Estuario: San Juan, Puerto Rico, 2024; Available online: https://estuario.org (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Estuario de la Bahía de San Juan. Monitoreo Bacteriológico de Playas y Lagunas; Estuario de la Bahía de San Juan: San Juan, Puerto Rico, 2025; Available online: https://estuario.org/enterococos/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- EPA Method 1664A; Oil and Grease, n-Hexane Extractable Material (HEM) by Extraction and Gravimetry. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-08/documents/method_1664a_1999.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- EPA Method 353.2; Determination of Nitrate-Nitrite Nitrogen by Automated Colorimetry. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1993. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-08/documents/method_353-2_1993.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Standard Methods 4500-P A, B, E; Phosphorus. American Public Health Association, American Water Works Association, Water Environment Federation: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- EPA Method 200.7; Determination of Metals and Trace Elements in Water and Wastes by Inductively Coupled Plasma–Atomic Emission Spectrometry. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1994. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/esam/method-2007-determination-metals-and-trace-elements-water-and-wastes-inductively-coupled (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Chiquillo, K.L. (University of Puerto Rico, Rio Piedras, San Juan, Puerto Rico). Personal communication, 26 July 2024.

- Valderrama-Landeros, L.; Camacho-Cervantes, M.; Velázquez-Salazar, S.; Villeda-Chávez, E.; Flores-Verdugo, F.; Flores-de-Santiago, F. Detection of an invasive plant (Cissus verticillata) in the largest mangrove system on the eastern Pacific coast—A remote sensing approach. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2025, 33, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos, S. (Estuario, San Juan, Puerto Rico); Chiquillo, K.L. (University of Puerto Rico, Rio Piedras, San Juan, Puerto Rico). Personal communication, 25 March 2024.

- Badrul Hisam, N.I.; Zakaria, M.Z.; Azid, A.; Abu Bakar, M.F.; Samsudin, M.S. Phytoremediation process of water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica) in absorbing heavy metal concentration in wastewater. J. Agrobiotechnol. 2022, 13, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Lead and Copper Rule; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/dwreginfo/lead-and-copper-rule (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. National Primary Drinking Water Regulations; Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/national-primary-drinking-water-regulations (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Percival, G.C.; Keary, I.P.; Noviss, K. The potential of a chlorophyll content SPAD meter to quantify nutrient stress in foliar tissue of sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus), English oak (Quercus robur), and European beech (Fagus sylvatica). Arbor. Urban. For. 2008, 34, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. Visualizing fit and lack of fit in complex regression models with predictor effect plots and partial residuals. J. Stat. Softw. 2018, 87, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, J.C.; Bates, D.M. Nonlinear mixed-effects models: Basic concepts and motivating examples. In Mixed-Effects Models in S and S-PLUS; Statistics and Computing; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 273–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schielzeth, H.; Dingemanse, N.J.; Nakagawa, S.; Westneat, D.F.; Allegue, H.; Teplitsky, C.; Réale, D.; Dochtermann, N.A.; Garamszegi, L.Z.; Araya-Ajoy, Y.G. Robustness of linear mixed-effects models to violations of distributional assumptions. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2020, 11, 1141–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenth, R.V. Least-squares means: The R package lsmeans. J. Stat. Softw. 2016, 69, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Puerto Rico, Department of Natural and Environmental Resources. Puerto Rico Water Quality Standards Regulation, as Amended in August 2022. Resolution No. 9079. 2022. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2014-12/documents/prwqs.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Orosco, M.; Merley, P. Evaluación de Plantas Arvenses de Reproducción Asexual Adaptadas al Cultivo de Cacao Para uso en Programa de Fitorremediación; Universidad UTE, Facultad de Ciencias de la Ingeniería a Industrias, Carrera De Ingeniería Ambiental y Manejo de Riesgos Naturales: Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, 2022; 65p, Available online: https://repositorio.ute.edu.ec/entities/publication/cc6480c5-b589-4784-8444-bfdde29b148a (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Soto Hidalgo, K.T.; Carrión-Huertas, P.J.; Kinch, R.T.; Betancourt, L.E.; Cabrera, C.R. Phytonanoremediation by Avicennia germinans (black mangrove) and nano zero valent iron for heavy metal uptake from Cienaga Las Cucharillas wetland soils. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2020, 14, 100363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannelli, M.A.; Pietrini, F.; Fiore, L.; Petrilli, L.; Massacci, A. Antioxidant response to cadmium in Phragmites australis plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2002, 40, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.S.; Chang, L.W. Heavy metal phytoremediation by water hyacinth at constructed wetlands in Taiwan. J. Aquat. Plant Manag. 2004, 42, 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Jiang, W.; Liu, C.; Xin, C.; Hou, W. Uptake and accumulation of lead by roots, hypocotyls and shoots of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea L.). Bioresour. Technol. 2000, 71, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, Z.; Arooj, F.; Ali, S.; Zaheer, I.E.; Rizwan, M.; Riaz, M.A. Phytoremediation of landfill leachate waste contaminants through floating bed technique using water hyacinth and water lettuce. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2019, 21, 1356–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tin Win, D.; Myint Myint, T.; Sein, T. Lead removal from industrial waters by water hyacinth. AU J. Technol. 2003, 6, 187–192. [Google Scholar]

- Sêkara, A.; Poniedziaek, M.; Ciura, J.; Jêdrszczyk, E. Cadmium and lead accumulation and distribution in the organs of nine crops: Implications for phytoremediation. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2005, 14, 509–516. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Phytoremediation Resource Guide; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development, National Risk Management Research Laboratory: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2000. Available online: https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPURL.cgi?Dockey=10002SEE.TXT (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Drobnik, J.; Barroncas de Oliveira, A. Cissus verticillata (L.) Nicolson and C.E. Jarvis (Vitaceae): Its identification and usage in the sources from 16th to 19th century. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 171, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haokip, N.; Gupta, A. Phytoremediation of chromium and manganese by Ipomoea aquatica Forssk. from aqueous medium containing chromium–manganese mixtures in microcosms and mesocosms. Water Environ. J. 2020, 35, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rane, N.R.; Swapnil, M.P.; Vishal, V.C.; Suhas, K.K.; Rahul, V.K.; Jyoti, P.J.; Sanjay, P.G. Ipomoea hederifolia rooted soil bed and Ipomoea aquatica rhizofiltration coupled phytoreactors for efficient treatment of textile wastewater. Water Res. 2016, 96, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izinyon, C.; Rawlings, A. Assessment of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) for phytoremediation of motor oil contaminated soil. Niger. J. Technol. 2013, 32. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | EPA Limit a | Average | Standard Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) | - | 28.70 | ±0.39 |

| pH | 6.0–9.0 | 7.00 | ±1.81 |

| Humidity (%) | - | 68.63 | ±2.82 |

| Dissolved Oxygen (mg/L) | >5.0 | 5.29 | ±0.32 |

| Conductivity (SPC) | <1000 | 0.23 | ±0.04 |

| Salinity (PPT) | <500 | 0.11 | ±0.02 |

| Oil and Grease (mg/L) | 50 | 2.60 | ±0.20 |

| Nitrate and Nitrite (mg/L) | 1.7 | 1.22 | ±0.31 |

| Total Phosphorus (mg/L) | 0.16 | 0.19 | ±0.03 |

| Lead—Total (mg/L) | 0.009 | BDL | BDL |

| Cadmium- Total (mg/L) | 0.008 | BDL | BDL |

| (a) Response variable: Cadmium | |||||

| Numerator DF | Denominator DF | F-value | p-value | ||

| Intercept | 1 | 12 | 10.194175 | 0.0077 | |

| Tissues | 2 | 12 | 9.009338 | 0.0041 | |

| (b) Tukey’s post hoc test: Cadmium | |||||

| estimate | SE | df | T-ratio | p-value | |

| Leaves–Roots | −1130.4 | 302 | 12 | −3.747 | 0.0073 |

| Leaves–Stems | −44.3 | 302 | 12 | −0.147 | 0.9882 |

| Roots–Stems | 1086.1 | 302 | 12 | 3.601 | 0.0094 |

| (a) Response variable: Lead | |||||

| Numerator DF | Denominator DF | F-value | p-value | ||

| Intercept | 1 | 12 | 32.48594 | 0.00001 | |

| Tissues | 2 | 12 | 30.42134 | 0.0001 | |

| (b) Tukey’s post hoc test: Lead | |||||

| estimate | SE | df | T-ratio | p-value | |

| Leaves–Roots | −868 | 127 | 12 | −6.829 | 0.0001 |

| Leaves–Stems | −19 | 302 | 12 | −0.150 | 0.9878 |

| Roots–Stems | 848 | 302 | 12 | 6.679 | 0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Velázquez, S.; Hidalgo, K.S.; Rivas, M.C.; Burgos, S.; Chiquillo, K.L. Flowing Towards Restoration: Cissus verticillata Phytoremediation Potential for Quebrada Juan Mendez in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Conservation 2025, 5, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation5040069

Velázquez S, Hidalgo KS, Rivas MC, Burgos S, Chiquillo KL. Flowing Towards Restoration: Cissus verticillata Phytoremediation Potential for Quebrada Juan Mendez in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Conservation. 2025; 5(4):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation5040069

Chicago/Turabian StyleVelázquez, Sofía, Keyla Soto Hidalgo, Monica C. Rivas, Sofía Burgos, and Kelcie L. Chiquillo. 2025. "Flowing Towards Restoration: Cissus verticillata Phytoremediation Potential for Quebrada Juan Mendez in San Juan, Puerto Rico" Conservation 5, no. 4: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation5040069

APA StyleVelázquez, S., Hidalgo, K. S., Rivas, M. C., Burgos, S., & Chiquillo, K. L. (2025). Flowing Towards Restoration: Cissus verticillata Phytoremediation Potential for Quebrada Juan Mendez in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Conservation, 5(4), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation5040069