Quantifying the Diversity of Normative Positions in Conservation Sciences

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Elaboration of a Typology of Normative Positions About Human–Nature Relationships

3. Results

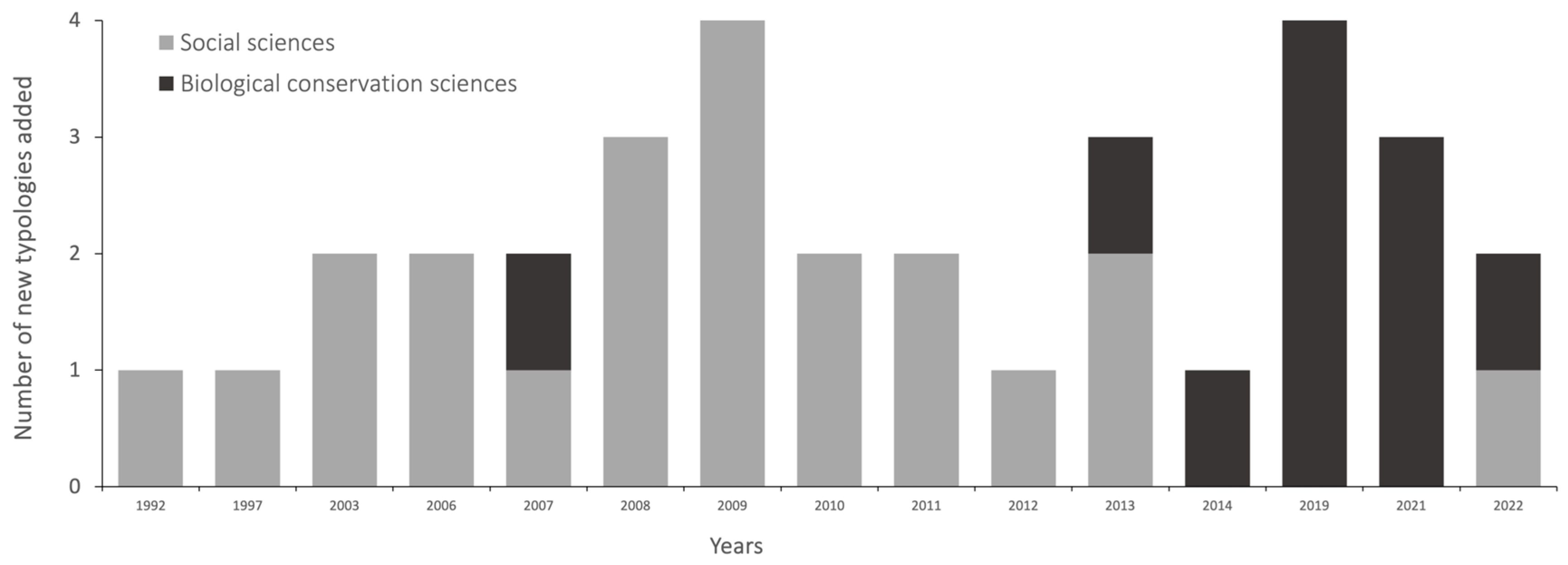

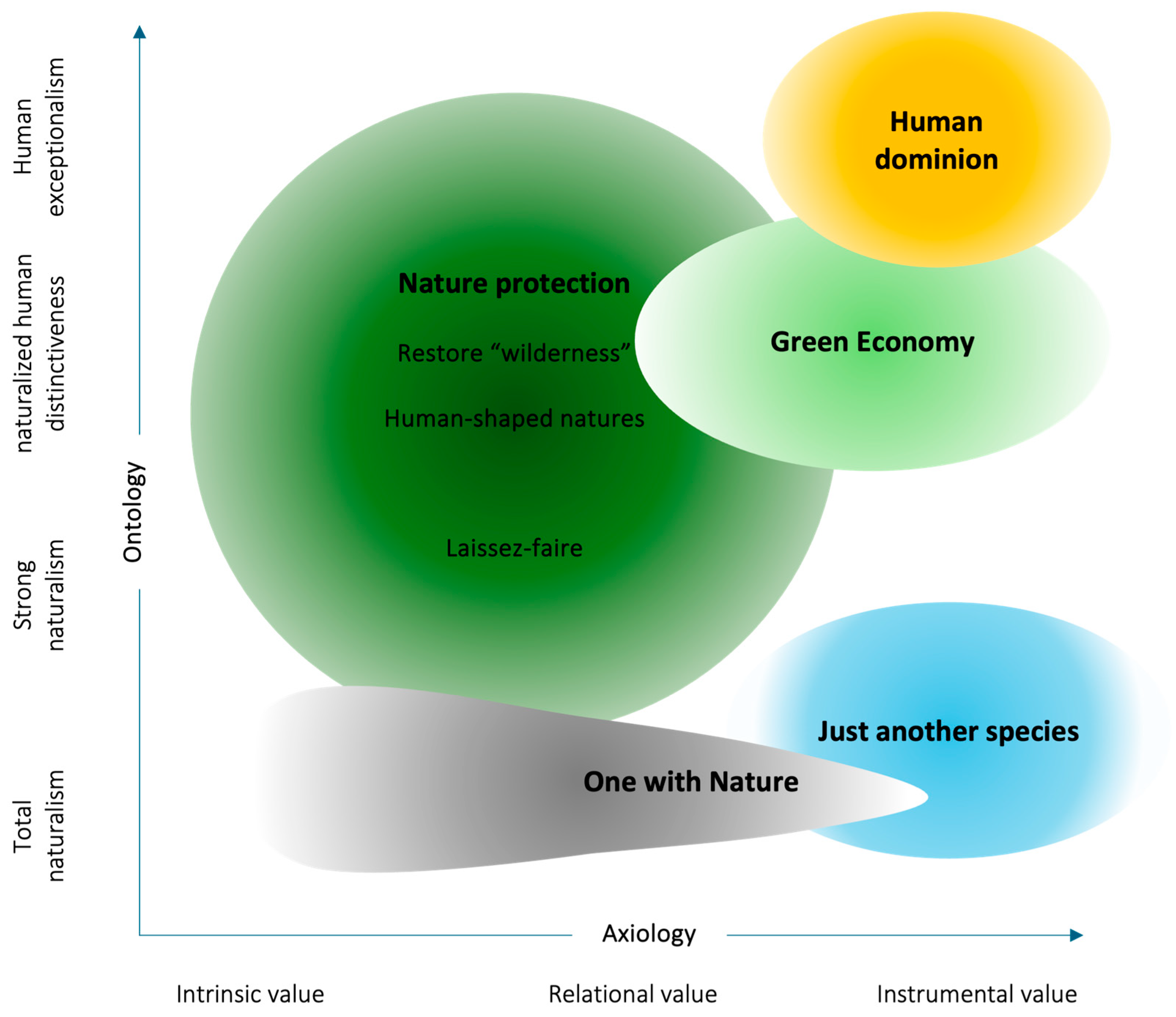

3.1. Pre-Existing Typologies and Dimensions of Human–Nature Interactions

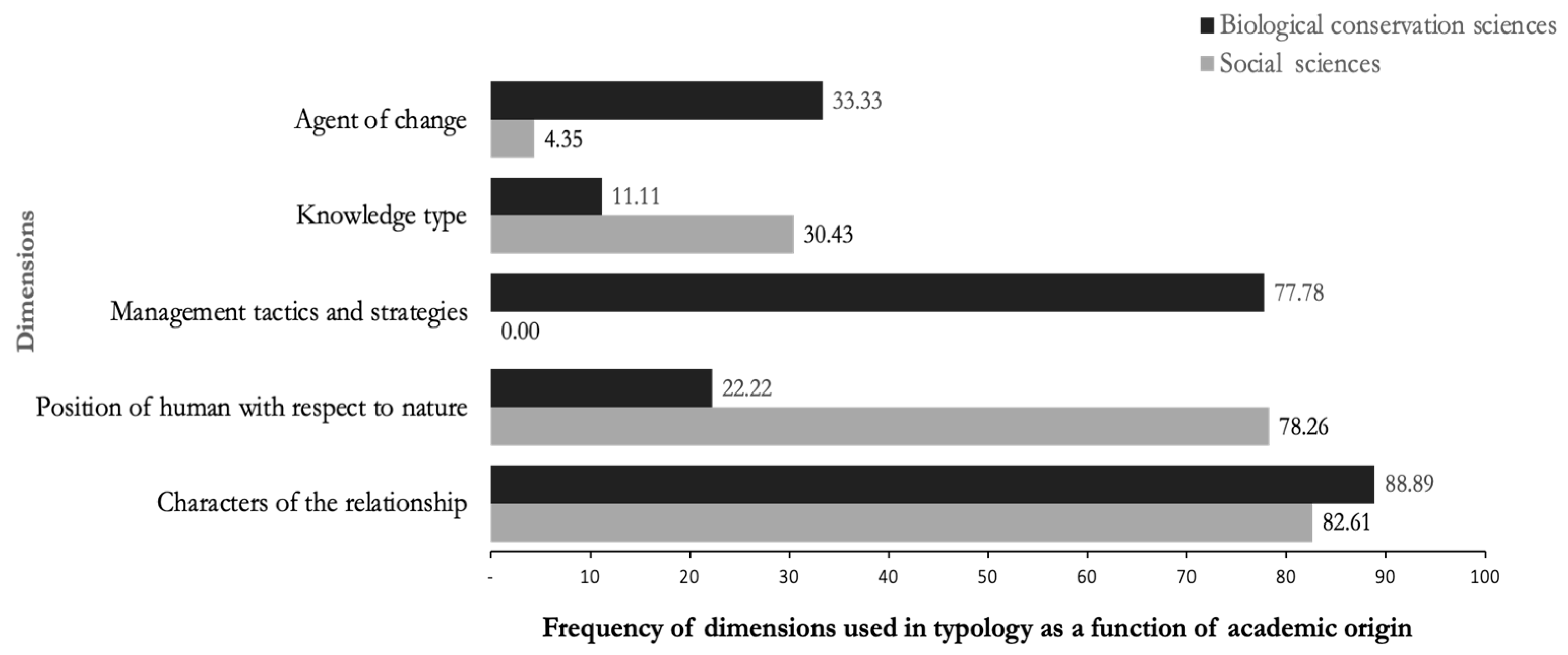

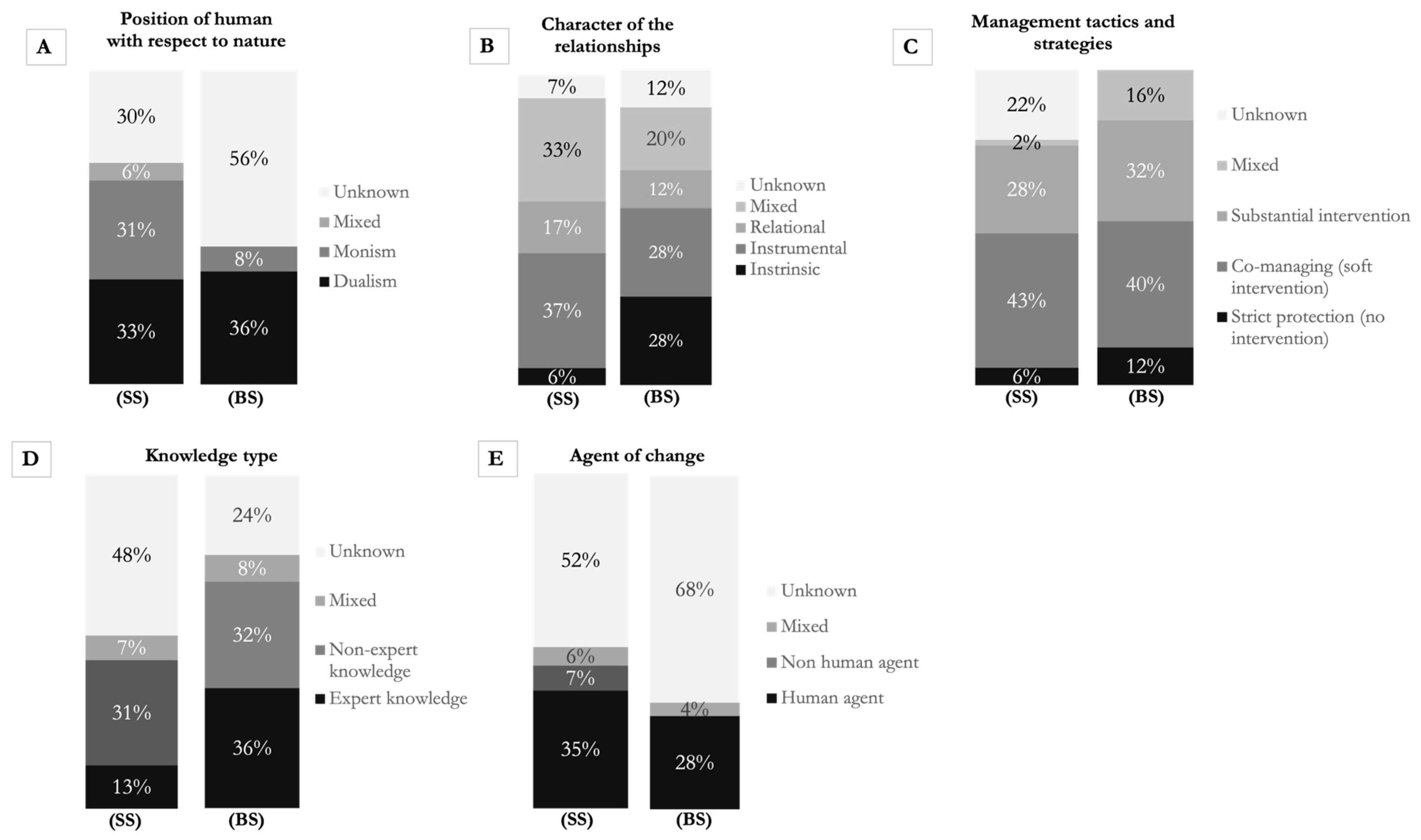

3.2. Value-States Within and Across Dimensions

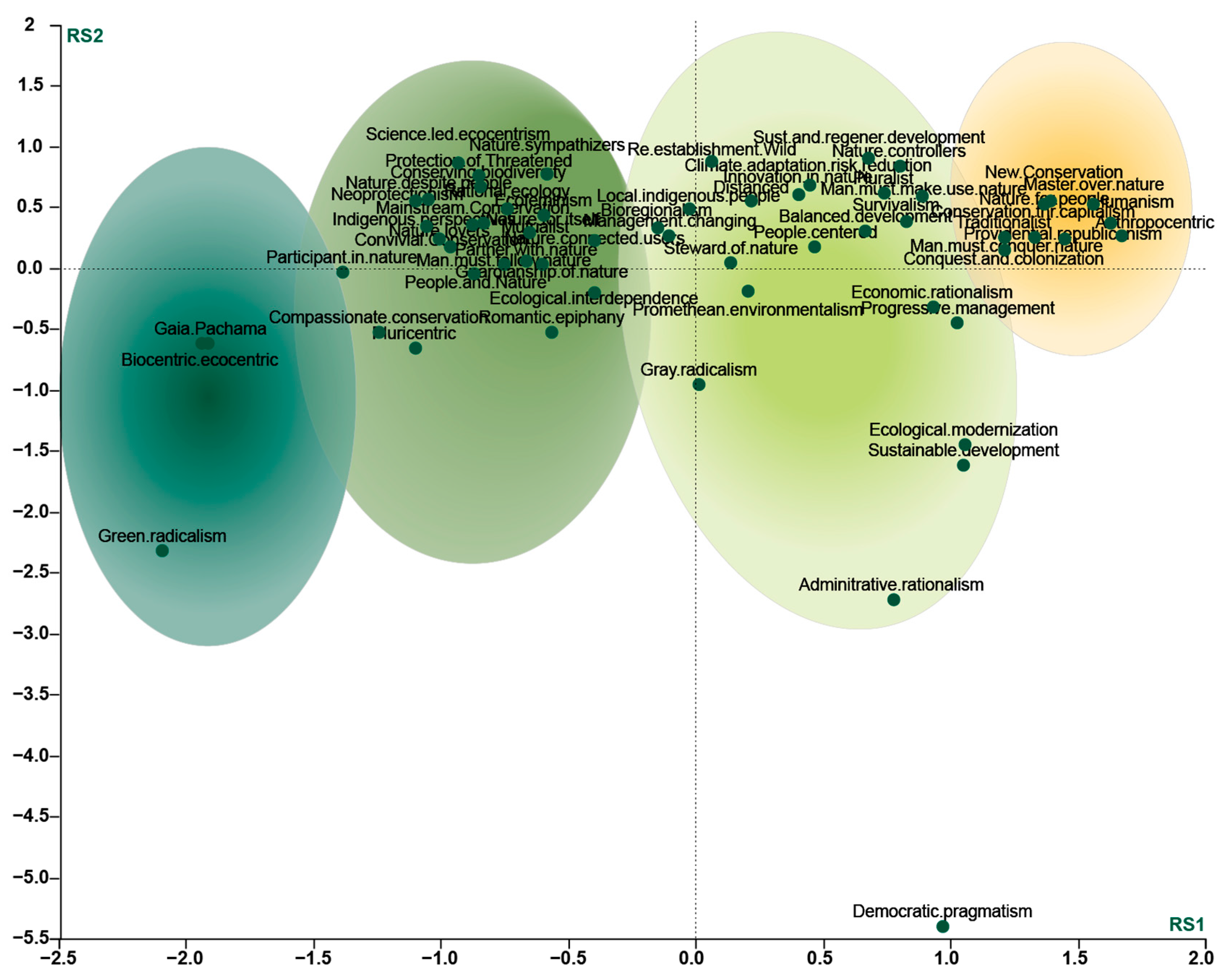

3.3. A Typology of the Normative Positions About Human–Nature Relationships

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chapman, M.; Satterfield, T.; Chan, K.M.A. How value conflicts infected the science of riparian restoration for endangered salmon habitat in America’s Pacific Northwest: Lessons for the application of conservation science to policy. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 244, 108508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, G.C.; Söderqvist, T.; Aniyar, S.; Arrow, K.; Dasgupta, P.; Ehrlich, P.R.; Folke, C.; Jansson, A.; Jansson, B.-O.; Kautsky, N.; et al. The value of nature and the nature of value. Science 2000, 289, 395–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascual, U.; Balvanera, P.; Díaz, S.; Pataki, G.; Roth, E.; Stenseke, M.; Watson, R.T.; Başak Dessane, E.; Islar, M.; Kelemen, E.; et al. Valuing nature’s contributions to people: The IPBES approach. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 26–27, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wienhues, A.; Luuppala, L.; Deplazes-Zemp, A. The moral landscape of biological conservation: Understanding conceptual and normative foundations. Biol. Conserv. 2023, 288, 110350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Riper, C.J.; Browning, M.H.; Becker, D.; Stewart, W.; Suski, C.D.; Browning, L.; Golebie, E. Human-nature relationships and normative beliefs influence behaviors that reduce the spread of aquatic invasive species. Environ. Manag. 2019, 63, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbrugge, L.N.; Van den Born, R.J.; Lenders, H. Exploring public perception of non-native species from a visions of nature perspective. Environ. Manag. 2013, 52, 1562–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPBES. Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; Brondízio, E.S., Settele, J., Diaz, S., Ngo, H.T., Eds.; IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2019; p. 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPBES (IPBES Secretariat). Methodological Assessment Report on the Diverse Values and Valuation of Nature of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; Balvanera, P., Pascual, U., Christie, M., Baptiste, B., González-Jiménez, D., Eds.; IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buscher, B.; Fletcher, R. The Conservation Revolution: Radical Ideas for Saving Nature Beyond the Anthropocene; Verso Books: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.; Gomez-Baggethun, E.; Quaas, M.; Rozzi, R.; Tauro, A.; Faith, D.P.; Kumar, R.; O’Farrell, P.; Pascual, U. Plural values of nature help to understand contested pathways to sustainability. One Earth 2024, 7, 806–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obura, D.O.; Katerere, Y.; Mayet, M.; Kaelo, D.; Msweli, S.; Mather, K.; Harris, J.; Louis, M.; Kramer, R.; Teferi, T. Integrate biodiversity targets from local to global levels. Science 2021, 373, 746–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascual, U.; Adams, W.M.; Díaz, S.; Lele, S.; Mace, G.M.; Turnhout, E. Biodiversity and the challenge of pluralism. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 4, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; De Vries, W.; De Wit, C.A. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büscher, B.; Fletcher, R. Towards convivial conservation. Conserv. Soc. 2019, 17, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koltko-Rivera, M.E. The psychology of worldviews. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2004, 8, 3–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, J.; Jafferally, D.; Ingwall-King, L.; Mendonca, S. Indigenous Knowledge. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, 2nd ed.; Kobayashi, A., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 211–215. [Google Scholar]

- Soulé, M.E.; Lease, G. Reinventing Nature?: Responses to Postmodern Deconstruction; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Pascual, U.; Balvanera, P.; Anderson, C.B.; Chaplin-Kramer, R.; Christie, M.; González-Jiménez, D.; Martin, A.; Raymond, C.M.; Termansen, M.; Vatn, A. Diverse values of nature for sustainability. Nature 2023, 620, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias-Arévalo, P.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Martín-López, B.; Pérez-Rincón, M. Widening the evaluative space for ecosystem services: A taxonomy of plural values and valuation methods. Environ. Values 2018, 27, 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.; O’Farrell, P.; Kumar, R.; Eser, U.; Faith, D.; Gomez-Baggethun, E.; Harmáčková, Z.V.; Horcea-Milcu, A.-I.; Merçon, J.; Quaas, M.; et al. The role of diverse values of nature in visioning and transforming towards just and sustainable futures. In Methodological Assessment Report on the Diverse Values and Valuation of Nature of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; Christie, M., Balvanera, P., Pascual, U., Baptiste, B., González-Jiménez, D., Eds.; IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, B.; Soulé, M.E.; Terborgh, J. New conservation’or surrender to development. Anim. Conserv. 2014, 17, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaepfer, M.A. Do non-native species contribute to biodiversity? PLoS Biol. 2018, 16, e2005568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skandrani, Z. From “what is” to “what should become” conservation biology? Reflections on the discipline’s ethical fundaments. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2016, 29, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulé, M. The “New Conservation”. Conserv. Biol. 2013, 27, 895–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matulis, B.S.; Moyer, J.R. Beyond Inclusive Conservation: The Value of Pluralism, the Need for Agonism, and the Case for Social Instrumentalism. Conserv. Lett. 2017, 10, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajeva, G. Assessing the values of nature to promote a sustainable future. Nature 2023, 620, 735–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kareiva, P.; Marvier, M. What is conservation science? BioScience 2012, 62, 962–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvier, M. New conservation is true conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2014, 28, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brockington, D.; Duffy, R. Capitalism and Conservation; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Büscher, B.; Dressler, W.; Fletcher, R. Nature Inc.: Environmental Conservation in the Neoliberal Age; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, R. Failing Forward: The Rise and Fall of Neoliberal Conservation; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Spash, C.L. Conservation in conflict: Corporations, capitalism and sustainable development. Biol. Conserv. 2022, 269, 109528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbedomon, R.C.; Salako, V.K.; Schlaepfer, M.A. Diverse views among scientists on non-native species. NeoBiota 2020, 54, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, S.; Clement, S. Novel decisions and conservative frames. In Governing the Anthropocene: Novel Ecosystems, Transformation and Environmental Policy; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Germany, 2021; pp. 97–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, R.J.; Arico, S.; Aronson, J.; Baron, J.S.; Bridgewater, P.; Cramer, V.A.; Epstein, P.R.; Ewel, J.J.; Klink, C.A.; Lugo, A.E. Novel ecosystems: Theoretical and management aspects of the new ecological world order. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2006, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaepfer, M.A.; Lawler, J.J. Conserving biodiversity in the face of rapid climate change requires a shift in priorities. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2023, 14, e798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skandrani, Z.; Lepetz, S.; Prévot-Julliard, A.-C. Nuisance species: Beyond the ecological perspective. Ecol. Process. 2014, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, D.M. Disagreement or denialism? “Invasive species denialism” and ethical disagreement in science. Synthese 2021, 198, 6085–6113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiaşu, R.C.; Tindale, C.W. Logical fallacies and invasion biology. Biol. Philos. 2018, 33, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagoff, M. Environmental harm: Political not biological. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2009, 22, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sax, D.F.; Schlaepfer, M.A.; Olden, J.D. Identifying key points of disagreement in non-native impacts and valuations. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2023, 38, 501–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koudenburg, N.; Kashima, Y. A polarized discourse: Effects of opinion differentiation and structural differentiation on communication. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2022, 48, 1068–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandbrook, C.; Fisher, J.A.; Holmes, G.; Luque-Lora, R.; Keane, A. The global conservation movement is diverse but not divided. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descola, P. Beyond Nature and Culture; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey, B. Understanding conflicting views in conservation: An analysis of England. Land Use Policy 2021, 104, 105362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryzek, J.S. The Politics of the Earth: Environmental Discourses; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2022; p. 304. [Google Scholar]

- Flint, C.G.; Kunze, I.; Muhar, A.; Yoshida, Y.; Penker, M. Exploring empirical typologies of human–nature relationships and linkages to the ecosystem services concept. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 120, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mace, G.M. Whose conservation? Science 2014, 345, 1558–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purdy, J. American natures: The shape of conflict in environmental law. Harv. Environ. Law Rev. 2012, 36, 170–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chevene, F.; Doleadec, S.; Chessel, D. A fuzzy coding approach for the analysis of long-term ecological data. Freshw. Biol. 1994, 31, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dray, S.; Dufour, A.-B. The ade4 package: Implementing the duality diagram for ecologists. J. Stat. Softw. 2007, 22, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, R.C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- De Castro, E.V. Cosmological deixis and Amerindian perspectivism. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 1998, 4, 469–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, B.; Porter, C. We Have Never Been Modern; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Betz, N.; Helmuth, B.; Coley, J.D. Conceptualizing human–nature relationships: Implications of human exceptionalist thinking for sustainability and conservation. Top. Cogn. Sci. 2023, 15, 357–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essl, F.; Lenzner, B.; Bacher, S.; Bailey, S.; Capinha, C.; Daehler, C.; Dullinger, S.; Genovesi, P.; Hui, C.; Hulme, P.E. Drivers of future alien species impacts: An expert-based assessment. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 4880–4893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPBES. Summary for Policymakers of the Methodological Assessment Report on the Diverse Values and Valuation of Nature of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; Pascual, U., Balvanera, P., Christie, M., Baptiste, B., González-Jiménez, D., Anderson, C.B., Athayde, S., Barton, D.N., Chaplin-Kramer, R., Jacobs, S., et al., Eds.; IPBES: Bonn, Germany, 2022; p. 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomo, I.; Locatelli, B.; Otero, I.; Colloff, M.; Crouzat, E.; Cuni-Sanchez, A.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; González-García, A.; Grêt-Regamey, A.; Jiménez-Aceituno, A. Assessing nature-based solutions for transformative change. One Earth 2021, 4, 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.C. Re-conceptualizing the role(s) of science in biodiversity conservation. Environ. Conserv. 2021, 48, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, S.; Kenter, J.O. Making intrinsic values work; integrating intrinsic values of the more-than-human world through the Life Framework of Values. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 1247–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccaro, I.; Beltran, O.; Paquet, P.A. Political ecology and conservation policies: Some theoretical genealogies. J. Political Ecol. 2013, 20, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, B. Streitfall Natur: Weltbilder in Technik-und Umweltkonflikten (Clashes on Nature—Worldviews in Technological and Environmental Conflicts); Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Meske, M. “Natur Ist für Mich Die Welt”: Lebensweltlich Geprägte Naturbilder von Kindern (“Nature is the World for Me”: Children’s Images of Nature Impressed by Their Environment); Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot, M.; Drenthen, M.; De Groot, W.T. Public visions of the human/nature relationship and their implications for environmental ethics. Environ. Ethics 2011, 33, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teel, T.L.; Manfredo, M.J. Understanding the diversity of public interests in wildlife conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2010, 24, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinhückelkotten, S.; Nietzke, H. Consciousness of Nature 2011 (ZA5079; Version 1.0.0) [Data Set]; GESIS: Cologne, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, N.; Wallner, A.; Hunziker, M. The change of European landscapes: Human-nature relationships, public attitudes towards rewilding, and the implications for landscape management in Switzerland. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 2910–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Groot, M.; de Groot, W.T. “Room for river” measures and public visions in the Netherlands: A survey on river perceptions among riverside residents. Water Resour. Res. 2009, 45, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunka, A.D.; De Groot, W.T.; Biela, A. Visions of nature in Eastern Europe: A Polish example. Environ. Values 2009, 18, 429–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Born, R.J.; de Groot, W.T. The authenticity of nature: An exploration of lay people’s interpretations in the Netherlands. In New Visions of Nature; Drenthen, M., Keulartz, F., Proctor, J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Born, R.J. Rethinking nature: Public visions in the Netherlands. Environ. Values 2008, 17, 83–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buijs, A.E.; Fisher, A.; Rink, D.; Young, J.C. Looking beyond superficial knowledge gaps: Understanding public representations of biodiversity. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Manag. 2008, 4, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berghöfer, U.; Rozzi, R.; Jax, K. Local versus global knowledge: Diverse perspectives on nature in the Cape Horn Biosphere Reserve. Environ. Ethics 2008, 30, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büscher, B.; Whande, W. Whims of the winds of time? Emerging trends in biodiversity conservation and protected area management. Conserv. Soc. 2007, 5, 22–43. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26392870 (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Fischer, A.; Young, J.C. Understanding mental constructs of biodiversity: Implications for biodiversity management and conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2007, 136, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bögeholz, S. Nature experience and its importance for environmental knowledge, values and action: Recent German empirical contributions. Environ. Educ. Res. 2006, 12, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Born, R.J. Implicit philosophy: Images of relationships between humans and nature in the Dutch population. In Visions of Nature. A Scientific Exploration of People’s Implicit Philosophies Regarding Nature in Germany, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom; Van den Born, R.J.G., Lenders, R.H.J., de Groot, W.T., Eds.; LIT Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2006; pp. 63–83. [Google Scholar]

- de Groot, W.; van den Born, R.J. Visions of nature and landscape type preferences: An exploration in The Netherlands. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 63, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Yoshino, R. Diversity patterns of attitudes toward nature and environment in Japan, USA, and European nations. Behaviormetrika 2003, 30, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R. The value of life: Biological diversity and human society. J. Wildl. Manag. 1997, 61, 1443–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osherenko, G. Human/nature relations in the Arctic: Changing perspectives. Polar Rec. 1992, 28, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Peterson, G.D.; Cheung, W.W.; Ferrier, S.; Alkemade, R.; Arneth, A.; Kuiper, J.J.; Okayasu, S.; Pereira, L.; Acosta, L.A. Towards a better future for biodiversity and people: Modelling Nature Futures. Glob. Environ. Change 2023, 82, 102681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronon, W. The Trouble with Wilderness; or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature. In Environmentalism: Critical Concepts; Pepper, D., Revill, G., Webster, F., Eds.; W. W. Norton & Co: New York, NY, USA, 1995; Volume 2, pp. 69–90. [Google Scholar]

- Skandrani, Z. Considering the socio-ecological co-construction of nature conceptions as a basis for urban environmental governance. J. Geogr. Nat. Disasters 2016, 6, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Rethinking Wilderness; Broadview Press: Peterborough, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, G. Éthiques de la Nature; The Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J. The ecology of human–nature interactions. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2020, 287, 20191882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storlie, T. Person-Centered Communication with Older Adults: The Professional Provider’s Guide; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, C.N. Progress developing the concept of other effective area-based conservation measures. Conserv. Biol. 2024, 38, e14106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkes, F.; Usher, P.J. Sacred knowledge, traditional ecological knowledge & resource management. Arctic 2000, 53, 198. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn, E. How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, A.; Salleh, A.; Escobar, A.; Demaria, F.; Acosta, A. Pluriverse: A Post-Dev. Dictionary; Tulika Books: New Dehli, India, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Dimension | Values-States from the Literature | Consolidated Value-States |

|---|---|---|

| Position of humans with respect to nature (ontology) | Human exceptionalism, Total naturalism, Naturalized human distinctiveness; Strong naturalism, Dominion (master of nature), Stewardship of nature, Egalitarian, Reverence to nature, Biophobia (fear of nature), Biophilia, Unconcerned | Monism, Dualism, Mixed, Unknown |

| Character of the relationship between humans and nature (axiology) | Intrinsic value (living with), Instrumental value (living in/from), Relational value (living as) | Intrinsic, Instrumental, Relational, Mixed, Unknown |

| Management tactics and strategies (pragmatism) | No human intervention (strict protection), Light intervention, Directed intervention, Biotechnology, Pristine nature, Nature with some alteration, Domestic nature | Substantial intervention, Co-management (soft intervention), Strict protection (no intervention), Mixed, Unknown |

| Knowledge type (epistemology) | Technical, Scientific, Indigenous, Democratic (lay people) | Expert knowledge, Non-expert knowledge, Mixed, Unknown |

| Agents of change (agency) | Market, Government, Corporate, People | Human agent, Non-human agent, Mixed, Unknown |

| Nr | Names of Normative Positions within Each Typology | Dimensions | Reference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | Ax | P | E | Ag | |||

| 1 | Survivalism; Promethean environmentalism; Administrative rationalism; Democratic pragmatism; Economic rationalism; Sustainable development; Ecological modernization; Green radicalism; Gray radicalism |  |  |  |  |  | [46] |

| 2 | Anthropocentric; Bio/ecocentric; Pluricentric |  |  |  |  |  | [57] |

| 3 | Conserving biodiversity—reducing degradation; Local and indigenous people; Biodiversity-friendly development; Climate adaptation and disaster risk reduction |  |  |  |  |  | [58] |

| 4 | Management of changing; Innovation in nature; Protection of threatened; Re-establishment of wild nature |  |  |  |  |  | [45] |

| 5 | Nature for itself; Nature despite people; Nature for people; People and nature; Peoples and natures |  |  |  |  |  | [59] |

| 6 | Mainstream conservation; Neo-protectionism; New conservation; Convivial conservation |  |  |  |  |  | [14] |

| 7 | People-centered; Science-led ecocentrism; Conservation through capitalism |  |  |  |  |  | [43] |

| 8 | Living from nature; Living in nature; Living with nature; Living as nature |  |  |  |  |  | [60] |

| 9 | Master over nature; Steward of nature; Partner with nature; Participant in nature |  |  |  |  |  | [5] |

| 10 | Nature for itself; Nature despite people; Nature for people; People and nature |  |  |  |  |  | [48] |

| 11 | Animism; Totemism; Analogism; Naturalism |  |  |  |  |  | [44] |

| 12 | Fortress conservation; Co-managing conservation; Neoliberal conservation |  |  |  |  |  | [61] |

| 13 | Identity discourse; Utilitarian discourse; Alternative discourse |  |  |  |  |  | [62] |

| 14 | Providential republicanism; Progressive management; Romantic epiphany; Ecological interdependence |  |  |  |  |  | [49] |

| 15 | Biocentric nature conservists; Non-reflected nature unionists; Unsure esthets; Family affected heritage of nature; Media oriented nature-dissociates |  |  |  |  |  | [63] |

| 16 | Master; Guardian; Partner; Participant |  |  |  |  |  | [64] |

| 17 | Traditionalist (mastery); Pluralist (domination + mutualism); Mutualist (egalitarian); Distanced |  |  |  |  |  | [65] |

| 18 | Master of nature; Partner of nature; Nature is superior; Conservation oriented; Unconcerned; Nature connected; Use oriented; Uninterested; Distanced |  |  |  |  |  | [66] |

| 19 | Nature-connected users; Nature-sympathizers; Nature controllers; Nature lovers |  |  |  |  |  | [67] |

| 20 | Master over nature; Guardianship of nature; Companionship with nature; Participant in nature |  |  |  |  |  | [68] |

| 21 | Conqueror of nature; Steward of nature; Spiritual participant in nature |  |  |  |  |  | [69] |

| 22 | Master over nature; Steward of nature; Partner with nature; Participant in nature |  |  |  |  |  | [70] |

| 23 | Master over nature; Partner with nature; Steward of nature; Participant in Nature |  |  |  |  |  | [71] |

| 24 | Humans as part of nature; Humans as participants in nature; Humans as responsible managers; Humans as separate from nature; Humans as stewards; Humans as enemies; Humans as users and engineers |  |  |  |  |  | [72] |

| 25 | Embedded relationship with nature; Cultivating relationship; Changing relationship; Resource-use relationship; Intellectual relationship; No direct relationship; Esthetic relationship |  |  |  |  |  | [73] |

| 26 | Neoliberal conservation; Bioregional conservation; Hijacked conservation |  |  |  |  |  | [74] |

| 27 | Humans as potential enemies of nature; Humans as users of nature; Humans as active managers of nature |  |  |  |  |  | [75] |

| 28 | Esthetic; Social; Instrumental–scientific; Ecological–scientific (investigative) |  |  |  |  |  | [76] |

| 29 | Master over nature; Steward of nature; Active partner with nature; Romantic partner with nature; Participant in nature |  |  |  |  |  | [77] |

| 30 | Man the adventurer and exploiter of nature; Man responsible for nature; Man the participant in nature |  |  |  |  |  | [78] |

| 31 | Man must follow nature; Man must make use of nature; Man must conquer nature |  |  |  |  |  | [79] |

| 32 | Utilitarian; Naturalistic; Ecologistic–scientific; Esthetic; Symbolic; Humanistic; Moralistic; Dominionistic; Negativistic |  |  |  |  |  | [80] |

| 33 | Conquest and colonization; Balanced development; Sustainable development; Rational ecology; Ecofeminism; Indigenous perspectives |  |  |  |  |  | [81] |

| Frequency (out of 33) | 27 | 20 | 8 | 9 | 5 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gbedomon, R.C.; Salako, K.V.; Delorme, D.; Schlaepfer, M.A. Quantifying the Diversity of Normative Positions in Conservation Sciences. Conservation 2025, 5, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation5030038

Gbedomon RC, Salako KV, Delorme D, Schlaepfer MA. Quantifying the Diversity of Normative Positions in Conservation Sciences. Conservation. 2025; 5(3):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation5030038

Chicago/Turabian StyleGbedomon, Rodrigue Castro, Kolawolé Valère Salako, Damien Delorme, and Martin A. Schlaepfer. 2025. "Quantifying the Diversity of Normative Positions in Conservation Sciences" Conservation 5, no. 3: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation5030038

APA StyleGbedomon, R. C., Salako, K. V., Delorme, D., & Schlaepfer, M. A. (2025). Quantifying the Diversity of Normative Positions in Conservation Sciences. Conservation, 5(3), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation5030038