Ozone Pollution and Urban Greening

Abstract

1. Introduction

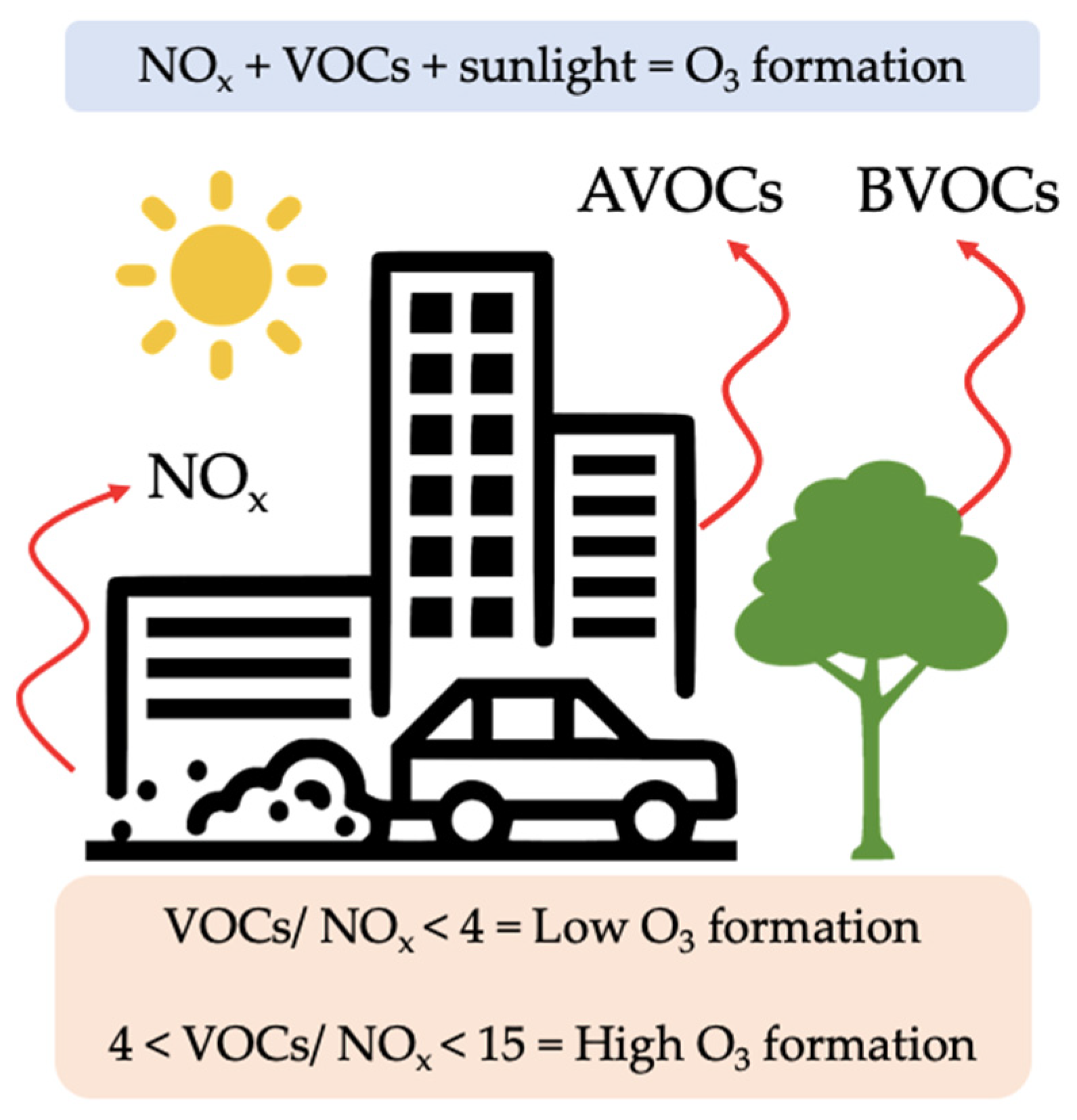

2. Mechanisms of Ozone Formation and Removal

3. Effectiveness and Limitations of Urban Greening

3.1. The Choice of Plant Species

3.2. The Choice of Plant Site and Nature-Based Solution

4. Urban Planning and Management Considerations

4.1. Actions on the Urban Environment

4.2. Actions on the Urban Policy

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cheesman, A.W.; Brown, F.; Artaxo, P.; Farha, M.N.; Folberth, G.A.; Hayes, F.J.; Heinrich, V.H.A.; Hill, T.C.; Mercado, L.M.; Oliver, R.J.; et al. Reduced Productivity and Carbon Drawdown of Tropical Forests from Ground-Level Ozone Exposure. Nat. Geosci. 2024, 17, 1003–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Strode, S.A.; Liang, Q.; Oman, L.D.; Colarco, P.R.; Fleming, E.L.; Manyin, M.E.; Douglass, A.R.; Ziemke, J.R.; Lamsal, L.N.; et al. Change in Tropospheric Ozone in the Recent Decades and Its Contribution to Global Total Ozone. JGR Atmos. 2022, 127, e2022JD037170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Li, T.; Zhou, Y.; Zong, L.; Wang, M.; Xie, Z.; Ho, H.C.; Gao, M.; et al. Substantially Underestimated Global Health Risks of Current Ozone Pollution. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anenberg, S.C.; Mohegh, A.; Goldberg, D.L.; Kerr, G.H.; Brauer, M.; Burkart, K.; Hystad, P.; Larkin, A.; Wozniak, S.; Lamsal, L. Long-Term Trends in Urban NO2 Concentrations and Associated Paediatric Asthma Incidence: Estimates from Global Datasets. Lancet Planet. Health 2022, 6, e49–e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malashock, D.A.; DeLang, M.N.; Becker, J.S.; Serre, M.L.; West, J.J.; Chang, K.-L.; Cooper, O.R.; Anenberg, S.C. Estimates of Ozone Concentrations and Attributable Mortality in Urban, Peri-Urban and Rural Areas Worldwide in 2019. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 054023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southerland, V.A.; Brauer, M.; Mohegh, A.; Hammer, M.S.; Van Donkelaar, A.; Martin, R.V.; Apte, J.S.; Anenberg, S.C. Global Urban Temporal Trends in Fine Particulate Matter (PM2·5) and Attributable Health Burdens: Estimates from Global Datasets. Lancet Planet. Health 2022, 6, e139–e146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sicard, P.; Agathokleous, E.; Anenberg, S.C.; De Marco, A.; Paoletti, E.; Calatayud, V. Trends in Urban Air Pollution over the Last Two Decades: A Global Perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 160064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhao, B.; Weschler, C.J. Assessing the Influence of Indoor Exposure to “Outdoor Ozone” on the Relationship between Ozone and Short-Term Mortality in U.S. Communities. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Seo, J.H.; Weon, S. Visualizing Indoor Ozone Exposures via O-Dianisidine Based Colorimetric Passive Sampler. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 460, 132510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslanoğlu, R.; Kazak, J.K.; Szewrański, S.; Świąder, M.; Arciniegas, G.; Chrobak, G.; Jakóbiak, A.; Turhan, E. Ten Questions Concerning the Role of Urban Greenery in Shaping the Future of Urban Areas. Build. Environ. 2025, 267, 112154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Qian, H. A Comprehensive Review of the Environmental Benefits of Urban Green Spaces. Environ. Res. 2024, 252, 118837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erell, E. Urban Greening and Microclimate Modification. In Greening Cities; Tan, P.Y., Jim, C.Y., Eds.; Advances in 21st Century Human Settlements; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 73–93. ISBN 978-981-10-4111-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrini, F.; Fini, A.; Mori, J.; Gori, A. Role of Vegetation as a Mitigating Factor in the Urban Context. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raihan, A. A Review on the Role of Green Vegetation in Improving Urban Environmental Quality. Eco Cities 2024, 4, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeland, S.; Moretti, M.; Amorim, J.H.; Branquinho, C.; Fares, S.; Morelli, F.; Niinemets, Ü.; Paoletti, E.; Pinho, P.; Sgrigna, G.; et al. Towards an Integrative Approach to Evaluate the Environmental Ecosystem Services Provided by Urban Forest. J. For. Res. 2019, 30, 1981–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reklaitiene, R.; Grazuleviciene, R.; Dedele, A.; Virviciute, D.; Vensloviene, J.; Tamosiunas, A.; Baceviciene, M.; Luksiene, D.; Sapranaviciute-Zabazlajeva, L.; Radisauskas, R.; et al. The Relationship of Green Space, Depressive Symptoms and Perceived General Health in Urban Population. Scand. J. Public Health 2014, 42, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Berg, M.; Wendel-Vos, W.; Van Poppel, M.; Kemper, H.; Van Mechelen, W.; Maas, J. Health Benefits of Green Spaces in the Living Environment: A Systematic Review of Epidemiological Studies. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 806–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, V.; Bamkole, O. The Relationship between Social Cohesion and Urban Green Space: An Avenue for Health Promotion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Xie, G.; Gao, J.; Yang, Y. The Cooling Effect of Urban Green Spaces as a Contribution to Energy-Saving and Emission-Reduction: A Case Study in Beijing, China. Build. Environ. 2014, 76, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, M.B. The Value of Urban Green Infrastructure and Its Environmental Response in Urban Ecosystem: A Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 4, 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Buccolieri, R.; Gromke, C.; Di Sabatino, S.; Ruck, B. Aerodynamic Effects of Trees on Pollutant Concentration in Street Canyons. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 5247–5256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzky, A.C.; Sandén, H.; Karl, T.; Fares, S.; Calfapietra, C.; Grote, R.; Saunier, A.; Rewald, B. The Interplay Between Ozone and Urban Vegetation—BVOC Emissions, Ozone Deposition, and Tree Ecophysiology. Front. For. Glob. Change 2019, 2, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolverton, B.C.; Mcdonald, R.C.; Watkins, E.A. Foliage plants for removing indoor air pollutants from energy-efficient homes. Econ. Bot. 1984, 38, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.H.; Hill, A.C. Absorption of Gaseous Air Pollutants By a Standardized Plant Canopy. J. Air Pollut. Control. Assoc. 1973, 23, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Wang, J.; Mathur, R.; Wang, S.; Sarwar, G.; Pleim, J.; Hogrefe, C.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Wong, D.C.; et al. Impacts of Aerosol Direct Effects on Tropospheric Ozone through Changes in Atmospheric Dynamics and Photolysis Rates. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 9869–9883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soni, V.; Singh, P.; Shree, V.; Goel, V. Effects of VOCs on Human Health. In Air Pollution and Control; Sharma, N., Agarwal, A.K., Eastwood, P., Gupta, T., Singh, A.P., Eds.; Energy, Environment, and Sustainability; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 119–142. ISBN 978-981-10-7184-3. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, S.; Guenther, A.; Faiola, C. Effects of Anthropogenic and Biogenic Volatile Organic Compounds on Los Angeles Air Quality. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 12191–12201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, T.; Price, S.; Bowler, D.; Hookway, A.; King, S.; Konno, K.; Richter, R.L. How Effective Is ‘Greening’ of Urban Areas in Reducing Human Exposure to Ground-Level Ozone Concentrations, UV Exposure and the ‘Urban Heat Island Effect’? An Updated Systematic Review. Environ. Evid. 2021, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonn, B.; Von Schneidemesser, E.; Butler, T.; Churkina, G.; Ehlers, C.; Grote, R.; Klemp, D.; Nothard, R.; Schäfer, K.; Von Stülpnagel, A.; et al. Impact of Vegetative Emissions on Urban Ozone and Biogenic Secondary Organic Aerosol: Box Model Study for Berlin, Germany. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 176, 827–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaerth, H.L.; Silva, S.J.; Li, Y. Characterizing Ozone Sensitivity to Urban Greening in Los Angeles Under Current Day and Future Anthropogenic Emissions Scenarios. JGR Atmos. 2023, 128, e2023JD039199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedow, J.M.; Ainsworth, E.A.; Li, S. Plant Biochemistry Influences Tropospheric Ozone Formation, Destruction, Deposition, and Response. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2021, 46, 992–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Situ, S.; Hao, Y.; Xie, S.; Li, L. Enhanced Summertime Ozone and SOA from Biogenic Volatile Organic Compound (BVOC) Emissions Due to Vegetation Biomass Variability during 1981–2018 in China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2022, 22, 2351–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, N. On the Role of Plant Volatiles in Anthropogenic Global Climate Change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 8563–8569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasooriya, V.M.; Ng, A.W.M.; Muthukumaran, S.; Perera, B.J.C. Green Infrastructure Practices for Improvement of Urban Air Quality. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 21, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.J.; Hirabayashi, S.; Doyle, M.; McGovern, M.; Pasher, J. Air Pollution Removal by Urban Forests in Canada and Its Effect on Air Quality and Human Health. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calfapietra, C.; Morani, A.; Sgrigna, G.; Di Giovanni, S.; Muzzini, V.; Pallozzi, E.; Guidolotti, G.; Nowak, D.; Fares, S. Removal of Ozone by Urban and Peri-Urban Forests: Evidence from Laboratory, Field, and Modeling Approaches. J. Environ. Qual. 2016, 45, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, S.; Agrawal, M. Effect of Ozone on Physiological and Biochemical Processes of Plants. In Tropospheric Ozone and Its Impacts on Crop Plants; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 65–113. ISBN 978-3-319-71872-9. [Google Scholar]

- Calfapietra, C.; Fares, S.; Manes, F.; Morani, A.; Sgrigna, G.; Loreto, F. Role of Biogenic Volatile Organic Compounds (BVOC) Emitted by Urban Trees on Ozone Concentration in Cities: A Review. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 183, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivatt, P.D.; Evans, M.J.; Lewis, A.C. Suppression of Surface Ozone by an Aerosol-Inhibited Photochemical Ozone Regime. Nat. Geosci. 2022, 15, 536–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, W.P.L. Development of Ozone Reactivity Scales for Volatile Organic Compounds. Air Waste 1994, 44, 881–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierravanti, A.; Fierravanti, E.; Cocozza, C.; Tognetti, R.; Rossi, S. Eligible Reference Cities in Relation to BVOC-Derived O 3 Pollution. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 28, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicard, P. Ground-Level Ozone over Time: An Observation-Based Global Overview. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2021, 19, 100226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiol, M.; Agostinelli, C.; Formenton, G.; Tarabotti, E.; Pavoni, B. Thirteen Years of Air Pollution Hourly Monitoring in a Large City: Potential Sources, Trends, Cycles and Effects of Car-Free Days. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 494–495, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anav, A.; De Marco, A.; Friedlingstein, P.; Savi, F.; Sicard, P.; Sitch, S.; Vitale, M.; Paoletti, E. Growing Season Extension Affects Ozone Uptake by European Forests. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 669, 1043–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fares, S.; Conte, A.; Alivernini, A.; Chianucci, F.; Grotti, M.; Zappitelli, I.; Petrella, F.; Corona, P. Testing Removal of Carbon Dioxide, Ozone, and Atmospheric Particles by Urban Parks in Italy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 14910–14922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicard, P.; De Marco, A.; Dalstein-Richier, L.; Tagliaferro, F.; Renou, C.; Paoletti, E. An Epidemiological Assessment of Stomatal Ozone Flux-Based Critical Levels for Visible Ozone Injury in Southern European Forests. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 541, 729–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogt, J.; Gillner, S.; Hofmann, M.; Tharang, A.; Dettmann, S.; Gerstenberg, T.; Schmidt, C.; Gebauer, H.; Van De Riet, K.; Berger, U.; et al. Citree: A Database Supporting Tree Selection for Urban Areas in Temperate Climate. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 157, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.Y.C.; Tsui, J.K.Y.; Chen, F.; Yip, W.-K.; Vrijmoed, L.L.P.; Liu, C.-H. Effects of Urban Vegetation on Urban Air Quality. Landsc. Res. 2011, 36, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirabayashi, S.; Kroll, C.N.; Nowak, D.J.; Endreny, T.A. I-Tree Eco Dry Deposition Model Descriptions, Version 1.5; i-Tree Tools: Syracuse, NY, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.itreetools.org/documents/60/i-Tree_Eco_Dry_Deposition_Model_Descriptions_V1.5.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Fares, S.; Alivernini, A.; Conte, A.; Maggi, F. Ozone and Particle Fluxes in a Mediterranean Forest Predicted by the AIRTREE Model. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 682, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzini, J.; Hoshika, Y.; Carrari, E.; Sicard, P.; Watanabe, M.; Tanaka, R.; Badea, O.; Nicese, F.P.; Ferrini, F.; Paoletti, E. FlorTree: A Unifying Modelling Framework for Estimating the Species-Specific Pollution Removal by Individual Trees and Shrubs. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 85, 127967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicard, P.; Agathokleous, E.; De Marco, A.; Paoletti, E. Ozone-Reducing Urban Plants: Choose Carefully. Science 2022, 377, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, B.B.; Nissim, W.G.; Manzini, J.; Scartazza, A.; Labra, M.; Hoshika, Y.; Sicard, P.; Zaldei, A.; De Marco, A.; Paoletti, E. The Role of Urban Forests in Tackling Air and Soil Pollution in Italian Cities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 113, 129066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmond, J.A.; Williams, D.E.; Laing, G.; Kingham, S.; Dirks, K.; Longley, I.; Henshaw, G.S. The Influence of Vegetation on the Horizontal and Vertical Distribution of Pollutants in a Street Canyon. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 443, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromke, C.; Ruck, B. Influence of Trees on the Dispersion of Pollutants in an Urban Street Canyon—Experimental Investigation of the Flow and Concentration Field. Atmos. Environ. 2007, 41, 3287–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.; McNulty, S.; Wang, P. The Mitigation Strategy of Automobile Generated Fine Particle Pollutants by Applying Vegetation Configuration in a Street-Canyon. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 274, 122941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicard, P.; Agathokleous, E.; Araminiene, V.; Carrari, E.; Hoshika, Y.; De Marco, A.; Paoletti, E. Should We See Urban Trees as Effective Solutions to Reduce Increasing Ozone Levels in Cities? Environ. Pollut. 2018, 243, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gourdji, S. Review of Plants to Mitigate Particulate Matter, Ozone as Well as Nitrogen Dioxide Air Pollutants and Applicable Recommendations for Green Roofs in Montreal, Quebec. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 241, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perivoliotis, D.; Arvanitis, I.; Tzavali, A.; Papakostas, V.; Kappou, S.; Andreakos, G.; Fotiadi, A.; Paravantis, J.A.; Souliotis, M.; Mihalakakou, G. Sustainable Urban Environment through Green Roofs: A Literature Review with Case Studies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getter, K.L.; Rowe, D.B. The Role of Extensive Green Roofs in Sustainable Development. Hortscience 2006, 41, 1276–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbid, Y.; Richard, C.; Sleiman, M. Towards an Experimental Approach for Measuring the Removal of Urban Air Pollutants by Green Roofs. Build. Environ. 2021, 205, 108286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, D.B. Green Roofs as a Means of Pollution Abatement. Environ. Pollut. 2011, 159, 2100–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraldi, R.; Neri, L.; Costa, F.; Facini, O.; Rapparini, F.; Carriero, G. Ecophysiological and Micromorphological Characterization of Green Roof Vegetation for Urban Mitigation. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 37, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Wang, D.; Ye, Q.; Zhang, J.; Liu, M.; Liu, H.; Yu, K.; Wang, Y.; Hou, E.; Zhong, B.; et al. Stomatal Responses of Terrestrial Plants to Global Change. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, J.; Ingwers, M.; McGuire, M.A.; Teskey, R.O. Stomatal Conductance Increases with Rising Temperature. Plant Signal. Behav. 2017, 12, e1356534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselmo-Moreira, F.; Da Silva Pedrosa, G.; Da Silva, I.L.; Do Nascimento, A.; Dos Santos, T.C.; Catharino, E.L.M.; Gomes, E.P.C.; Borbon, A.; Fornaro, A.; De Souza, S.R. Biogenic Volatile Organic Compound (BVOC) Emission Profiles from Native Atlantic Forest Trees: Seasonal Variation and Atmospheric Implications in Southeastern Brazil. Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 104, 128645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirasteh-Anosheh, H.; Saed-Moucheshi, A.; Pakniyat, H.; Pessarakli, M. Stomatal Responses to Drought Stress. In Water Stress and Crop Plants; Ahmad, P., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 24–40. ISBN 978-1-119-05436-8. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z.; Yuan, X.; Fares, S.; Loreto, F.; Li, P.; Hoshika, Y.; Paoletti, E. Isoprene Is More Affected by Climate Drivers than Monoterpenes: A Meta-analytic Review on Plant Isoprenoid Emissions. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 1939–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peñuelas, J.; Staudt, M. BVOCs and Global Change. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forestry Serving Urbanised Societies: Selected Papers from the Conference Held in Copenhagen, Denmark, from 27 to 30 August 2002; IUFRO European Regional; Konijnendijk, C.C., Schipperijn, J., Hoyer, K.K., Eds.; IUFRO world series; International Union of Forestry Research Organizations: Vienna, Austria, 2004; ISBN 978-3-901347-49-8. [Google Scholar]

- Rötzer, T.; Moser-Reischl, A.; Rahman, M.A.; Grote, R.; Pauleit, S.; Pretzsch, H. Modelling Urban Tree Growth and Ecosystem Services: Review and Perspectives. In Progress in Botany Vol. 82; Cánovas, F.M., Lüttge, U., Risueño, M.-C., Pretzsch, H., Eds.; Progress in Botany; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 82, pp. 405–464. ISBN 978-3-030-68619-2. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, D.J.; Hirabayashi, S.; Bodine, A.; Greenfield, E. Tree and Forest Effects on Air Quality and Human Health in the United States. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 193, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo, F.J.; Kroeger, T.; Wagner, J.E. Urban Forests and Pollution Mitigation: Analyzing Ecosystem Services and Disservices. Environ. Pollut. 2011, 159, 2078–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Churkina, G.; Grote, R.; Butler, T.M.; Lawrence, M. Natural Selection? Picking the Right Trees for Urban Greening. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 47, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. Air Quality in Europe: 2020 Report; Publications Office: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Grange, S.K.; Lee, J.D.; Drysdale, W.S.; Lewis, A.C.; Hueglin, C.; Emmenegger, L.; Carslaw, D.C. COVID-19 Lockdowns Highlight a Risk of Increasing Ozone Pollution in European Urban Areas. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 4169–4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicard, P.; Pascu, I.-S.; Petrea, S.; Leca, S.; Marco, A.D.; Paoletti, E.; Agathokleous, E.; Calatayud, V. Effect of Tree Canopy Cover on Air Pollution-Related Mortality in European Cities: An Integrated Approach. Lancet Planet. Health 2025, 9, e527–e537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament & Council of the European Union Regulation (EU) 2024/1991 of 24 June 2024 on Nature Restoration and Amending Regulation (EU) 2022/869. 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1991/oj/eng (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Konijnendijk, C.C. Evidence-Based Guidelines for Greener, Healthier, More Resilient Neighbourhoods: Introducing the 3–30–300 Rule. J. For. Res. 2023, 34, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, M.A.; Marco, A.D.; Anav, A.; Sorrentino, B.; Paoletti, E.; Manzini, J.; Hoshika, Y.; Sicard, P. The 3–30–300 Rule Compliance: A Geospatial Tool for Urban Planning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2025, 261, 105396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anav, A.; Sorrentino, B.; Collalti, A.; Paoletti, E.; Sicard, P.; Coulibaly, F.; Manzini, J.; Hoshika, Y.; De Marco, A. Meteorological, Chemical and Biological Evaluation of the Coupled Chemistry-Climate WRF-Chem Model from Regional to Urban Scale. An Impact-Oriented Application for Human Health. Environ. Res. 2024, 257, 119401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sicard, P.; Coulibaly, F.; Lameiro, M.; Araminiene, V.; De Marco, A.; Sorrentino, B.; Anav, A.; Manzini, J.; Hoshika, Y.; Moura, B.B.; et al. Object-Based Classification of Urban Plant Species from Very High-Resolution Satellite Imagery. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 81, 127866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Low-BVOC-Emitting Species | High-BVOC-Emitting Species |

|---|---|

| Lindens (Tilia × europaea; Tilia cordata; Tilia platyphyllos) | Oaks (Quercus ilex; Quercus pubescens; Quercus petraea) |

| Maples (Acer campestre; Acer platanoides; Acer pseudoplatanus) | Willows (Salix alba; Salix babylonica) |

| Hornbeams (Ostrya carpinifolia; Carpinus betulus) | Eucalypts (Eucalyptus glaucescens; Eucalyptus globulus) |

| Ash trees (Fraxinus excelsior; Fraxinus angustifolia) | Poplars (Populus nigra; Populus alba; Populus tremula) |

| Recommendation | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Select low-BVOC, high O3-removal species. | Reduce O3 formation in the air and maximize O3 removal by species. |

| Use green roofs to supplement trees. | Add pollutant removal capacity, especially where tree planting is limited. |

| Irrigate plants. | No drought stress reduces BVOC emissions and increases stomatal O3 uptake. |

| In planting, consider the tree position. | Trees do not have to reduce ventilation in the city, e.g., do not plant tall trees along street canyons. |

| Avoid heavy pruning. | The lower the leaf biomass, the lower the O3 uptake and BVOC emissions, but pruning stress stimulates BVOC emissions. |

| Maintain good plant health. | Plants under stress emit more BVOCs. |

| Cool the air. | O3 formation increases with increasing temperature. |

| Incorporate into pollutant emission reduction policies. | Balances the effects of BVOC and NOx on O3 formation. |

| Respect the 3-30-300 rule. | Provide direct health benefits to the city inhabitants. |

| Target an average of 30% tree cover in a city. | Reduce the negative impacts of air pollution on human health. |

| Consider both private and public trees. | Support wise management of all urban green areas. |

| Tailor greening to local conditions. | Consider climate, pollution sources, and urban layout. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paoletti, E.; Sicard, P.; Marco, A.D.; Moura, B.B.; Manzini, J. Ozone Pollution and Urban Greening. Stresses 2025, 5, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/stresses5040065

Paoletti E, Sicard P, Marco AD, Moura BB, Manzini J. Ozone Pollution and Urban Greening. Stresses. 2025; 5(4):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/stresses5040065

Chicago/Turabian StylePaoletti, Elena, Pierre Sicard, Alessandra De Marco, Barbara Baesso Moura, and Jacopo Manzini. 2025. "Ozone Pollution and Urban Greening" Stresses 5, no. 4: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/stresses5040065

APA StylePaoletti, E., Sicard, P., Marco, A. D., Moura, B. B., & Manzini, J. (2025). Ozone Pollution and Urban Greening. Stresses, 5(4), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/stresses5040065