Abstract

A rest–pause (RP) technique involves performing one or more repetitions at high resistance to failure, followed by a short rest before performing one or more repetitions. These techniques can affect neuromuscular conditions and fatigue by changing the rest time between repetitions. This study compared the effect of 12 weeks of RP and traditional resistance training (TRT) on myokines (myostatin (MSTN), follistatin (FLST) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1)) and functional adaptations. The study recruited 29 men between the ages of 20 and 30 who had performed resistance training for at least 6 to 12 months. Participants were randomly divided into three groups: RP, TRT, and control; resistance training was performed 3 days per week for 12 weeks. The training methods of the two groups were largely similar. The results showed that RP increased IGF-1 and FLST/MSTN more than the TRT group (% change = 19.04, % change = 37.71), and only the RP and TRT groups had significant changes in the FLST/MSTN ratio compared to the control group (p < 0.001 and p = 0.02, respectively). In addition, FLST levels increased and MSTN decreased in the RP and TRT groups, but the rate of change in FLST was significant in the RP and TRT groups compared to the control group (p = 0.002 and p = 0.001, respectively). Leg press and bench press strength, and arm and thigh muscular cross-sectional area (MCSA) increased more in the RP group than in the others, and the percentage of body fat (PBF) decreased significantly. The change between strength and MCSA was significant (p ≤ 0.05), and the PBF change in RP and TRT compared to the control (ES RP group = 0.43; ES TRT group = 0.55; control group ES = 0.09) was significant (p = 0.005, p = 0.01; respectively). Based on the results, the RP training technique significantly affects strength and muscle hypertrophy more than the TRT method, which can be included in the training system to increase strength and hypertrophy.

1. Introduction

The various resistance training systems are divided into high volume and high intensity, which trainers and athletes commonly use. In these methods, the traditional techniques derived from advanced training are often used, and the new relaxation techniques are derived from advanced training. Each technique works with different volumes, strengths, frequencies, and rest periods. Traditional methods are the most common training methods. In this method, the athlete increases the weight in each set and completes the exercise with maximum strength. This method is used during strength and hypertrophy. The RP method is also the most popular training method today. Today, recreational and professional athletes regularly use the RP technique, which includes short rest periods between low, high repetitions [1]. This method involves lifting a specific weight to exhaustion (usually 10–12 reps) followed by short sets (3–4 sets) of high intensity (85–90% of 1RM) and short periods of rest (10–12 reps at 12 s.) and low frequency (2 to 5 repetitions) until complete physical exhaustion [2]. According to Paoli et al., RP training methods have been shown to use more energy and may require more energy than traditional resistance training (TRT) [3].

The metabolic stress of RP and the emphasis on the phosphogenic and glycolytic energy systems may differ from traditional multiset training [1]. For example, in the RP protocol, the exercise is performed initially at 80% 1RM, followed by subsequent sets in 20 s intervals for a total of 18 reps; about 8–12 reps of 80% 1RM in the first set will cause failure [4] in the phosphogene and glycolytic system for energy transfer. Since muscle phosphocreatine (PCr) levels can recover quickly [5], a 20 s interval after the first set allows for a relative PCr synthesis that makes it easier to perform more repetitions in the training set. These repetitions again (up to a total of 18) increase the level of metabolic load (from the first) and stimulate the expression of hypertrophy in the muscle [6].

Resistance training increases muscle mass [7], volume exercise [8], and the number of steps performed [9] in most healthy individuals; it is a characteristic of the physical training response used in training [10,11]. Muscle growth and hypertrophy caused by resistance training affect many factors, including myogenic regulatory factor (MRF), transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) such as myostatin (MSTN) and follistatin (FLST), and endocrine and paracrine growth hormone (GH) and insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1), whose metabolic activity increases protein synthesis and stimulates muscle fiber hypertrophy. MSTN is expressed and secreted in muscle cells, which is less expressed and secreted in various tissues such as the brain and adipose tissue, and has functions such as inhibiting the hypertrophic growth of muscle cells and the prevention of proliferation of these cells (inhibition of hyperplastic growth) [12]. FLST is a glycoprotein expressed and secreted in almost all mammalian tissues, especially skeletal muscle. The main function of FLST is to suppress the effects of TGF-β family proteins, including MSTN. In the case of FLST, the MSTN cannot connect to its receiver and functionality [13].

The effect of RP training on hormonal changes has not been investigated. Based on the evidence that RP training can achieve better metabolic response and repair than TRT, we hypothesize that RP training can significantly affect hormonal adjustments, strength and muscle hypertrophy. Therefore, to clarify the benefits of this technique and to solve the hormonal and functional confusion, this study aims to evaluate the effect of 12 weeks of RP and TRT on muscle activity and myokines in men.

2. Results

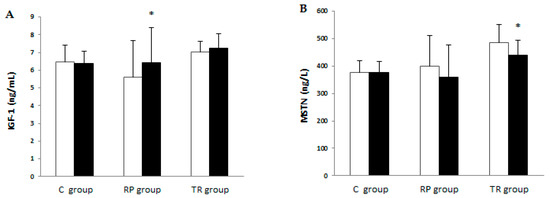

The descriptive characteristics of the subjects are RP group: age (years) = 25.64 ± 4.35, height (cm) = 176.10 ± 7.20, body mass (kg): 81.42 ± 12.53; TRT group: age (years) = 26.19±3.27, height (cm) = 180.70 ± 5.05, body mass (kg): 80.57±13.33; control group: age (years) = 24.39 ± 4.11, height (cm) = 174.88 ± 8.38, body mass (kg): 80.17 ± 19.56. According to the results of Figure 1, the levels of IGF-1, FLST and the ratio of FLST to MSTN increased significantly after 12 weeks of RP resistance training (ES = 0.41, p = 0.03; ES = 1.00, p = 0.001; ES = 1.40, p = 0.001; respectively), MSTN levels decreased but the changes were not significant (ES = 0.33, p = 0.07); In addition, in the RP group, strength of upper-body, lower-body, thigh and arm MCSA and SMM increased, and PBF decreased; the changes observed after 12 weeks of training were significant (ES = 2.03, p < 0.001; ES = 2.35, p < 0.001; ES = 1.38, p < 0.001; ES = 1.53, p < 0.001; ES = 0.25, p = 0.02; ES = 0.43, p = 0.02; respectively, Table 1).

Figure 1.

Changes in hormonal responses to resistance program (IGF-1 (A), MSTN (B), FLST (C), FLST/MSTN (D)). TR: traditional, RP: rest–pause, C: control, MSTN: myostatin, FLST: follistatin, IGF-1: insulin-like growth factor-1, EF: effect size. * denotes significant differences between baseline and post-testing values (p ≤ 0.05); # denotes significant differences between the RP and TR groups with the C group. (p ≤ 0.05).

Table 1.

Changes in body composition, muscle strength and hypertrophy in response to 12-week training intervention (mean ± SD).

As shown in Figure 1, changes in MSTN, FLST, and the ratio of FLST to MSTN were significant in the TRT group (ES = 0.73, p = 0.03; ES = 1.77, p < 0.001; ES = 2.63, p < 0.001; respectively), but although IGF-1 levels increased after 12 weeks of training, the observed changes were not significant (ES = 0.29, p = 0.57). According to the results of Table 1, changes in upper- and lower-body muscle strength, thigh and arm MCSA, BMI, SMM and PBF were significant after 12 weeks of TRT (ES = 1.77, p < 0.001; ES = 1.32, p < 0.001; ES = 0.70, p < 0.001; ES = 0.93, p < 0.001; ES = 0.20, p = 0.09; ES = 0.27, p = 0.01; ES = 0.55, p = 0.001, respectively). In addition, the observed changes were not significant in the control group (p > 0.05).

As depicted in Figure 1, the most remarkable alterations in IGF-1 levels were observed in the RP group, but the differences were insignificant (%Change = 19.04, p = 0.1). Additionally, the MSTN levels decreased in all three groups of patients with RP, TRT, and a control group, but the differences between the groups were insignificant (%Change = −10.08; %Change = −8.37; %Change = −0.32; respectively, p = 0.1). Conversely, FLST levels increased in the RP and TRT groups (%Change = 21.05 and %Change = 19.55; respectively) and these increases were significant compared to the control group (p = 0.002 and p = 0.001; respectively). The findings indicated that the largest increase in the FLST/MSTN ratio was in the RP group (%Change RP group = 37.71; %Change TRT group = 31.78; %Change control group = 0.27), and the changes in the RP and TRT groups were significant compared to the control group (p < 0.001; p = 0.02; respectively, Figure 1).

Upper- and lower-body muscle strength in the RP group increased more than the other groups, and the changes were significant in all groups (RP group upper-body: %Change = 74.90; RP group lower-body: %Change = 63.79; TRT group upper-body: %Change = 63.54; TRT group lower-body: %Change = 51.19; control group upper-body: %Change = −0.69; control group lower-body: %Change = 1.78; p< 0.006) (Table 1). Additionally, the increase rate in the thigh and arm MCSA in the RP group was higher than the other two groups, and the intergroup changes in all three groups were significant (RP group: thigh MCSA %Change = 32.86; arm MCSA %Change = 33.80; TRT group: thigh MCSA %Change = 17.72; arm MCSA %Change = 19.36; control group: thigh MCSA %Change = −0.25; arm MCSA %Change = −0.21; p < 0.05). Table 1 demonstrates that SMM levels increased in both the RP and TRT groups (a change of 3.48 and 4.58%, respectively); however, the increase in the TRT group was greater and was significant when compared to the control group (p = 0.02). Additionally, the differences in PBF levels between the RP and TRT groups and the control group were significant (p = 0.005 and p = 0.01, respectively). Contrastingly, there were no significant differences in BMI levels between the groups (p = 0.67) (Table 1).

3. Discussion

This study compared the effect of 12 weeks of RP versus TRT on muscle activity and myokines (MSTN, FLST, and IGF-1) in active men. The study showed that the practice of RP increases muscle strength and upper-body and lower-body MCSA and reduces PBF compared to the TRT. Furthermore, IGF-1 levels increased in the RP group, while MSTN levels decreased in the TR group, but the difference between the two groups was insignificant. Changes in FLST levels in the RP and TRT groups were significant compared to the control group. Moreover, the greatest increase in the FLST/MSTN ratio was observed in the RP group, with changes in the PR and TRT groups.

Resistance training stimulates muscle growth by increasing the positive effects of muscle growth and by suppressing the negative effects by increasing hypertrophy and hyperplasia. The rate of release of myokine and factors regulating muscle growth affect the volume and strength of the muscles involved in the activity [14]. Due to the loss of muscle mass and the expansion of protein synthesis, the main cause of muscle hypertrophy is stimulated [15]. The interest of these proteins is a signaling system that leads to a positive balance of myogenic factors such as FLST, Myo-D and c-fos, and a negative balance of myostatic factors such as MSTN. As a result, a good balance of the hypertrophic process is brought about by increasing the synthesis of synthetic proteins and the increase in the penetration of satellite cells by cells [16]. On the other hand, the intensity or level of resistance produced during resistance training can also affect motor unit activation. The number and type of active motor units also affect the level of secreted myokines and their autocrine and paracrine functions [17].

The current study showed that the RP training increased IGF-1 levels more than the TRT group, but the observed differences were not significant. In addition, FLST levels increased in both groups to a similar extent, but the changes in the control group were not significant. In addition, MSTN levels decreased in the RP and TRT groups, but the rate of decrease was not significant. The ratio of FLST to MSTN in the RP group was higher than in the others, and the differences between the groups in the RP and TRT were different compared to the controls. To date, no studies have investigated the effects of PR training on IGF-1, FLST, or MSTN levels. Some researchers have suggested that using different methods of resistance training can lead to a better anabolic environment and improve the effect of training on muscles [1,18,19,20]. For example, a drop set increases the metabolic stress due to the large number of consecutive repetitions performed [19,20]. In addition, by extending the time spent at high loads, RP can help to increase the workload [1,2]. Girman et al. [21] found no difference in GH between cluster and TRT in a group of trained men. Slow movement increases GH more than tempo movement, and tempo also plays an important role [22].

The RP system involves first lifting a fixed load to exhaustion (usually 10–12 repetitions) followed by subsequent sets using short rest intervals (10–20 s) [2]. The recommended amount of rest varied between repetitions in different studies. Increased mechanical stress (i.e., the time spent under stress associated with heavy loads) and metabolic stress (i.e., the accumulation of metabolites in the muscle, muscle hypoxia, and changes in the local myogenic factors) caused by the RP system can lead to an increase in muscle mass or strength by increasing the number of fibers used or by altering the release of myokin and the expansion of cells versus TRT [1,2,6,20]. Additionally, differences in amplitude of repetition may lead to a greater advantage for the glycolytic pathway in the RP group, which in turn may lead to greater muscle fiber swelling and metabolic stress, which appears to promote anabolism [6].

RP technique is one of the functional systems of the comprehensive high-intensity training (HIT) system [2]. HIT can increase testosterone, cortisol [22,23,24] and the testosterone-to-cortisol ratio [25,26]. The results of Elliott et al. showed that HIT increases plasma FLST in inactive subjects [27]. Regarding the role of MSTN and FLST in the response to resistance training, studies have shown that MSTN plasma levels decrease after several weeks of resistance training, whereas FLST concentrations increase after resistance training [28,29,30]. Activated muscle mass is a key determinant of endocrine anabolic hormone responses to resistance training [31,32]. Mourkioti et al. showed that FLST levels increase depending on the volume of active muscle groups [33]. In this study, an attempt was made to activate more muscle mass during the training session through primary movement. The present study attempted to activate muscle volume in training sessions using the main movements. These exercises significantly increased follistatin in both training groups. Myokine production can vary depending on various factors, including diet, lifestyle, medication, circadian rhythm, and several other factors [34]. It is possible that some of these influencing factors influenced the results of the current study, as they were considered part of the study’s limitations, in addition to controlling the subjects’ nutrition (a food recall questionnaire was used), assessing their familiarity and skills related to RP implementation and movement speed (tempo).

HIT increases the activation of signaling pathways associated with contractile proteins, thereby increasing myokine levels [16]. In our study, training RP as a HIT also increases the ratio of FLST to MSTN. Resistance training-induced muscle hypertrophy can be achieved by altering the balance of muscle protein synthesis, increasing molecular stimulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and Ca+2 signaling pathways, and inhibiting protein degradation pathways and apoptosis (such as forkhead boxes) to realize protein O (FOXO) [17]. MSTN and FLST in these processes are significant; FLST is essential for forming, growing, and developing muscle fibers [35]. Elevated FLST is a powerful agonist that stimulates all signaling pathways for protein synthesis and inhibits protein degradation pathways [35]. A significant increase in FLST stimulates all signaling pathways involved in protein synthesis and suppresses protein breakdown [35]. Further, FLST stimulates satellite cells, essential for muscle repair and development [16].

In addition to the role of FLST in the development of muscle tissue, it affects increasing bone growth and density by increasing osteoblastic activity and decreasing osteoclastic activity [36]; as well, its role in increasing fat metabolism and reducing fat stores has been reported [37]. However, an important part of the myogenic mechanisms of FLST is due to its function in suppressing members of the TGF-β family, especially MSTN [35]. FLST directly disrupts the function of MSTN by reducing levels of the free protein MSTN as well as by binding to its specific receptor, and it indirectly reduces the function of other members of the TGF-β family by activating certain mediators [35]. The mechanism of action of MSTN is the same as that of bidirectional FLST because, unlike FLST, it disrupts all intracellular anabolic pathways and protein synthesis by activating many SMAD proteins. Similar to FOXO, all catabolic processes are accelerated, eventually leading to muscle tissue atrophy [38]. Furthermore, MSTN receptors in adipose and bone tissue cells indicate the opposite function of MSTN to FLST in these tissues [37]. Thus, small changes in the levels of these myokines can play a role in the process of muscle and bone development as well as metabolic balances in the body [37]. Studies have shown that exogenously increasing FLST levels or suppressing MSTN gene expression, which causes a significant increase in fast-twitch fibers compared with slow-twitch fibers, promotes muscle hypertrophy. As a result of high-intensity training, fast-twitch motor units are more active, resulting in higher muscle myokines and myogenic factors [17,38]. On the other hand, previous research has shown exercise-induced muscle hypertrophy. This growth is dependent on levels of hormones such as GH, IGF-1, testosterone and cortisol, which are affected by how intensely and vigorously an exercise is performed [39].

Resistance training with higher intensity loads produces greater growth hormone levels than resistance training with lower intensity loads, which depends on the type of exercise (cardio vs. strength), how much work is done in a particular number of repetitions, and the muscle group being exercised [39]. Additionally, the exercise at a high frequency using lighter weights results in larger GH responses than working out at a slower pace with heavier weights [39]. Growth and tissue repair increase GH levels, which activate anabolic growth factors such as PI3K and IRS-1/2 [39]. Different factors affect hormonal adaptations, including exercise pattern, intensity, duration, tempo, and muscle group volume. This study investigated RP for the first time in the context of hormonal changes, with an increased ratio of IGF-1 and FLST to MSTN observed in both RP and TRT (higher in RP). Furthermore, MSTN was reported to have decreased (more so in TRT). However, drawing definitive conclusions from these results is difficult, and thus, more research is needed.

The results showed that changes in upper-body and lower-body strength, thigh and arm MCSA, SMM and PBF were significant in RP and TRT groups after 12 weeks of training. Upper- and lower-body muscle strength, and arm and thigh MCSA in the RP group increased more than in other groups; between-group changes were significant. The changes in PBF levels in the RP and TRT groups compared to the control group were significant. In addition, SMM increased in both groups, but significant changes were observed in the TRT group compared to the control group. The upper-body and lower-body strength increased a lot in the RP group (ES = 2.03, ES = 2.35; respectively); this could have been due to poor technique and lack of motivation at the start of the training protocol. Training for 12 weeks can improve people’s movement technique and increase their self-confidence and motivation. Additionally, the metabolic and hormonal responses associated with muscle failure provide a significant stimulus for strength and neuromuscular adaptations during RP training [2]. Regular training also leads to more physiological and neurological adaptations in recreational athletes, which is why their records can increase at the end of the training protocol. In this regard, we can refer to the study of Enes et al. [40], who found that RP produces a greater increase in muscle strength than TRT. After a 12-week resistance training program involving hypertrophic intensity, Oliver et al. found that trained men in the cluster training group had greater strength and power than those in the TRT group [41]. In contrast to these results, some studies [1,42] did not find a significant difference in muscle strength between the RP and TRT groups. According to Prestes et al., RP training is an effective method for building upper-body and lower-body muscle strength recreationally. The increased strength in the RP training was equivalent to the TRT [1]. In addition, Korak et al. in their study stated that while changes in strength and neural activation did not differ between groups, 1RMs increased in both groups [42]. Some studies have shown an increase in the strength of recreational and non-recreational athletes in both RP and traditional multi-set training systems [43,44].

In addition, Gantois et al. stated that RP and TRT to muscular failure would further reduce countermovement jump height and perceive more training load than non-failure training. RP system to muscular failure leads to higher acute neuromuscular dysfunction. RP non-failure had no effect on neuromuscular function and reduced training load and metabolic stress compared to other trials [45]. Regarding the increase in muscle hypertrophy, the results of Prestes et al. [1] and Korak et al. [42] were in line with the results of the present study. Prestes et al. showed that the RP system achieved better results in thigh muscle hypertrophy. They stated this because trainers often change training techniques in programs to continue to increase strength and muscle mass [1]; thus, if maximizing muscle endurance, hypertrophy, and time efficiency [2] are of primary importance, then the RP technique should be used instead of the TRT technique [1]. In addition, Korak et al. concluded that RP increases hypertrophy more than the TRT group. The RP system should be used if the training goal is to increase hypertrophy [42]. The pauses used in a set in RP training allow for some PCr to be regenerated.

However, studies have shown that complete re-synthesis of PCr after high-intensity training sessions may require ≥170 s [46]. It is possible that some PCr resynthesis occurred at this time. This can delay fatigue and increase muscle strength during RP training [42]. Although the underlying mechanisms are not well understood, it is speculated that more mechanical work will alter signaling pathways related to ribosome biogenesis and muscle protein synthesis [47,48], which ultimately increases muscular mass. Resistance training includes mechanical stimuli and is a decisive factor that increases skeletal muscle growth. This increase is caused by increased expression of IGF-1 or mechanical growth factor (MGF) protein, which leads to activation of successive signaling cascades PI3K and phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1) and Akt. After this, Akt activates two independent pathways: mammalian target point of rapamycin (mTOR) and glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β), which play a key role in skeletal muscle hypertrophy [49]. Resistance training increases resting metabolic rate (RMR) and sleeping metabolic rate (SMR). Resistance training also increases energy expenditure and decreases respiratory quotient (RQ) during rest and sleep 24 h after training. This decrease in RQ indicates greater reliance on fat as a fuel source [50]. Wang et al. stated that the energy expenditure associated with one kilogram of muscle tissue is approximately 13 kcal/day, and one kilogram of fat is approximately 4.5 kcal/day [51]. Therefore, energy expenditure seems to be an essential weight management strategy to protect against muscle tissue loss and, thus, better maintain RMR [50]. Hormonal changes are also associated with reduced body fat [52]. Due to the further increase in IGF-1 and the ratio of FLST to MSTN in the RP group, a further increase in muscle strength and hypertrophy can be justified. This training system can probably have more effects than the TRT system, but more research is needed to draw more accurate conclusions.

The present study had various limitations, including the time it took for subjects to get accustomed to and trained with the RP system. Furthermore, nutrition during training as well as circadian sleep of the subjects were assessed with questionnaires but were not regulated. Participants in this experiment were recreational athletes, and their initial skill level was relatively low. Consequently, techniques demonstrated by participants at the start of trials had to be corrected through meticulous training and monitoring. An advantage of amateur athletes is that neural changes leading to improved performance can be achieved within a few weeks, resulting in more adaptation than those who are already trained.

4. Materials and Methods

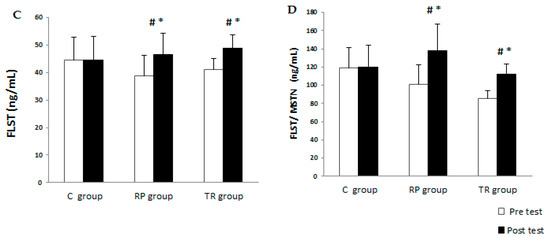

The study included thirty 20- to 30-year-old men who were not regularly active in the last year. They had to be in good physical and mental health. There were also no dietary supplements or medications that affected amino acid metabolism—especially beta blockers, beta agonists, calcium channel blockers, or corticosteroids. In addition to medical examinations for diseases or smoking habits, all participants were required to pass further tests. Following successful screening, subjects signed an informed consent form and were assigned to one of three groups (n = 10): RP, TRT and control (Figure 2). In accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration, the experiment was approved by IR.SSRC.REC.1400.060 of the Sports Science Research Institute.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of the study. TRT: traditional resistance training, RP: rest–pause, 1RM: one repetition maximum, myostatin: MSTN, follistatin: FLST, insulin-like growth factor-1: IGF-1.

4.1. Research Design

At an initial meeting with all participants and trainers, the goals and procedure of the study were clarified, while forms regarding the purpose and process of research were distributed. In addition, a medical questionnaire was provided. Subsequently, directions on performing RP training were given, and registered data included age, height (Seca, Germany), weight (Seca, Germany), body mass index (BMI), and other functional indicators. Strength tests (1RM) for each subject were performed according to methods by Niewiadomski et al. [53] and Barbalho et al. [54]. Muscle hypertrophy was calculated following Knapik et al.’s [55] as well as Heymsfield et al.’s [56] equations. Body composition was measured with the help of bioelectrical impedance analysis (InBody270, Korea). Plasma levels of MSTN, FLSF and IGF-1 were also checked before and after training through blood samples taken 48 h prior and post-training; however one of the control groups had to be excluded due to lack of cooperation in the second sampling stage. A control group had to be excluded because of poor cooperation during the second stage of blood sampling.

4.2. Procedure

The subjects were randomly divided into three groups each advised to follow the recommended diet while participating in a 12-week training period. Before commencing the training sessions, warm-up exercises lasting 5 min usually occurred, followed by stretching of every muscle (6–10 s). Each group was trained on alternating even and odd days three days per week. The movements selected involved: machine leg extension, leg press, machine lying leg curl, cable pull-down, seated cable row, dumbbell curl, barbell curl (for the first session), bench press, incline bench press, barbell shoulder press, dumbbell military press, cable push-down and barbell lying triceps extension (for the second), with the program for third session mirroring that of the first. The training programs of the two groups were identical in volume.

4.3. TRT Program

In the TRT, for each movement, 3 sets × 10 repetitions and in total 30 repetitions with an intensity of 70% 1RM, for the first to third week; 3 sets × 8 repetitions, a total of 24 repetitions with an intensity of 75% 1RM, for the fourth to sixth week; 3 sets × 6 repetitions and a total of 18 repetitions with 80% 1RM for the seventh to ninth week; 3 sets × 4 repetitions with a total of 12 repetitions with 85% 1RM, for the tenth to twelfth week with 2 min rest between sets, and 3 min were considered between different exercises (Table 2).

Table 2.

Training program for 12 weeks.

4.4. RP Resistance Training Program

RP involves several mini-sets. In the RP method, a fixed volume-load is prescribed and subsequent failure mini-sets are performed as required with short intra-set rest intervals (e.g., 30 s) after an initial failure mini-set (typically 10–12 repetitions). In this study, the RP technique was performed: athletes began training with 70% 1RM and continued training until complete muscle failure occurred. After 30 s of rest, they next performed mini-sets with rest intervals of 30 s to reach the number of repetitions in the TRT with the same intensity of activity (30 repetitions). The exercise was performed the same way from the fourth to the sixth weeks, with the rest period reduced to 25 s and intensity increased to 75% 1RM, and the repetitions were continued until the number of repetitions in the TRT were reached at the same intensity. From the seventh to the ninth week, the exercise intensity was adjusted to 80% of 1RM, followed by a 20 s pause, and continued at that intensity until 18 repetitions in TRT were completed. After the tenth and twelfth weeks, the intensity was increased to 85% 1RM, which reduced the time between short sets to 15 s, and the exercise was continued until a 12-repetition TRT was reached with the same intensity (Table 2).

4.5. Assessing the 1RM

Following the introduction and preparation of the subjects with different resistance exercises, the subjects were taken to a gym where they determined their 1RM for all selected stations using the Niewiadomski et al. method [53]. Thus, in order to prevent and minimize injury, subjects walked on the treadmill for five minutes in a low-intensity mode for general warm-up and then started performing eight repetitions with 50% 1RM (estimated approximately) for specific body warming. After one minute of rest, the subject performed three repetitions with an intensity of 70% of an estimated 1RM. After a 3 min rest, the subject repeated 3 to 5 attempts for 1RM. Barbalho et al. used a similar method to determine 1RM [54]. They provided a 3 to 5 min rest between each attempt and added 5% to the load.

4.6. Assessment of Muscle Hypertrophy

Muscular hypertrophy of the lower body was estimated by assessing the muscular cross-sectional area (MCSA) of the thigh based on the Knapik et al. equation using the following formula [55]:

Thigh MCSA (cm2) = 0.649 × ((CT/π − SQ)2 − (0.3 × dE)2)

CT: circumference thigh (cm), π: 3.14, SQ: skinfold quadriceps (cm), dE: distance epicondyles (cm).

Arm circumference by a tape measure (Iran) and a caliper (Harpenden, England) were used to measure the skinfold on the anterior midline of the thigh, and a caliper (Calsize, China) was used to measure the distance between the internal and external epicondyles of the femur.

Muscular hypertrophy of the upper body was also calculated by assessing the MCSA of the arm, using the equation of Heymsfield et al. [56]:

Arm MCSA (cm2) = π ((CA/2 π) − (TA/2))2 − 5.5

CA: circumference arm (cm), π: 3.14, TA: triceps skinfold arm (cm)

The arm circumference was measured by a tape measure, and skinfold of the triceps by a caliper.

4.7. Nutrient Intake and Dietary Analysis

The subjects were instructed on how to modify their diet following the recommendations of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, the Dietitians of Canada, and the American College of Sports Medicine. These recommendations distribute macronutrients (55–65% of total calories from carbohydrates, approximately 35% of total calories from fats and approximately 10–15% of total calories from protein) [50]. Except for these instances, subjects were instructed not to alter their diet during training. A questionnaire for a 3-day food recall (2 regular days and 1 off) was employed to assess caloric intake. Participants were instructed to document their diet for three days before the start of the program and for three days following the program’s final week of. Calories, carbohydrates, fats, and proteins consumed were calculated.

Each food item in the diet was analyzed in the program (Master diet pro, Iran) that is used to analyze diet data, the number of calories consumed was calculated, and the amount of energy from proteins, fats, and carbohydrates was compared using paired samples t tests. The results of Table 3 confirmed that no dietary changes occurred prior to or following the training period. Additionally, the lack of control over the subjects’ nutrition during the study was one of the limitations of the present investigation.

Table 3.

Dietary daily intake assessed for the groups (mean ± SD).

4.8. Assessment of Biochemical Indicators

Laboratory blood collection specialists took five milliliters of blood from the brachial vein from each subject on an empty stomach (between 8:00 and 9:00 in the morning). Blood samples were collected in test tubes with EDTA anticoagulant and centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 10 min, and serum samples were kept at −70 °C for subsequent measurements. Plasma levels of MSTN, FLST and IGF-1 were assessed by ELISA Kit to measure human myokines from the German company (ELISA, ZellBio GmbH, Ulm, Germany), for MSTN, FLST and IGF-1 by ELISA method according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The sensitivity was 0.02 ng/mL for IGF-1, 1 ng/mL for FLST, and 9 ng/L for MSTN.

4.9. Statistical Analysis

The distribution of each variable was evaluated via the Shapiro–Wilk test in order to verify that their distribution was normal. The paired samples t-test was employed to compare the pre- and post-test results in the two groups. The statistical significance of the results was evaluated using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA that took baseline values as a covariate). This allowed for the identification of potential interactions between time × group. Multiple comparisons were performed using the LSD (post hoc analysis) procedure after the results were obtained. All differences between the groups were examined more thoroughly via effect sizes (ES) (Cohen’s d). The magnitude of the ES statistics was considered trivial <0.20; small 0.20–0.50; moderate 0.50–0.80; large 0.80–1.30; and very large >1.30 [57]. For each variable, a percentage change score was calculated ((post—pre)/pre × 100). Statistical significance was designated at p ≤ 0.05 for these analyses. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

5. Conclusions

The RP training technique has a greater effect on strength and muscle hypertrophy than TRT, which can be incorporated into a training system to increase strength and hypertrophy. It seems that this training system can be employed to create more effective training than TRT for individuals. However, additional research is needed on the effects of the RP system versus the TRT system regarding hormonal adaptations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, H.A.; formal analysis, investigation, original draft preparation, M.K; writing—review and editing, M.K., H.A. and J.M.; supervision, H.A. and J.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the biochemistry laboratory of Mehr-e Chehel Sotun in Isfahan city for technical assistance of this work. We also gratefully appreciate the participants involved in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

References

- Prestes, J.; Tibana, R.A.; de Araujo Sousa, E.; da Cunha Nascimento, D.; de Oliveira Rocha, P.; Camarço, N.F.; de Sousa, N.M.; Willardson, J.M. Strength and muscular adaptations after 6 weeks of rest-pause vs. traditional multiple-sets resistance training in trained subjects. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, S113–S121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, P.; Robbins, D.; Wrightson, A.; Siegler, J. Acute neuromuscular and fatigue responses to the rest-pause method. J. Sci. Med. Sport. Med. Aust. 2012, 15, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paoli, A.; Moro, T.; Marcolin, G.; Neri, M.; Bianco, A.; Palma, A.; Grimaldi, K. High-Intensity Interval Resistance Training (HIRT) influences resting energy expenditure and respiratory ratio in non-dieting individuals. J. Transl. Med. 2012, 10, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimano, T.; Kraemer, W.J.; Spiering, B.A.; Volek, J.S.; Hatfield, D.L.; Silvestre, R.; Vingren, J.L.; Fragala, M.S.; Maresh, C.M.; Fleck, S.J.; et al. Relationship between the number of repetitions and selected percentages of one repetition maximum in free weight exercises in trained and untrained men. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2006, 20, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stull, G.A.; Clarke, D.H. Patterns of recovery following isometric and isotonic strength decrement. Med. Sci. Sports 1971, 3, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, B.J. Potential mechanisms for a role of metabolic stress in hypertrophic adaptations to resistance training. Sports Med. 2013, 43, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grgic, J.; Mcllvenna, L.C.; Fyfe, J.J.; Sabol, F.; Bishop, D.J.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Pedisic, Z. Does aerobic training promote the same skeletal muscle hypertrophy as resistance training? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2018, 49, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, B.J.; Ogborn, D.; Krieger, J.W. Effects of resistance training frequency on measures of muscle hypertrophy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 1689–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, J.W. Single vs. multiple sets of resistance exercise for muscle hypertrophy: A meta-analysis. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2010, 24, 1150–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, Y. Lateral specificity in resistance training: The effect of bilateral and unilateral training. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 1997, 75, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, Y. Relationship between the modifications of bilateral deficit in upper and lower limbs by resistance training in humans. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 1998, 78, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-J.; Lee, Y.-S.; Zimmers, T.A.; Soleimani, A.; Matzuk, M.M.; Tsuchida, K.; Cohn, R.D.; Barton, E.R. Barton, Regulation of muscle mass by follistatin and activins. Mol. Endocrinol. 2010, 24, 1998–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiroki, E.; Abe, S.; Iwanuma, O.; Sakiyama, K.; Yanagisawa, N.; Shiozaki, K.; Ide, Y. A comparative study of myostatin, follistatin and decorin expression in muscle of different origin. Anat. Sci. Int. 2011, 86, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motevalli, M.S.; Dalbo, V.J.; Attarzadeh, R.S.; Rashidlamir, A.; Tucker, P.S.; Scanlan, A.T. The Effect of Rate of Weight Reduction on Serum Myostatin and Follistatin Concentrations in Competitive Wrestlers. Int. J. Sports. Physiol. Perform. 2015, 10, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandri, M. Signaling in Muscle Atrophy and Hypertrophy. Physiology 2008, 23, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murach, K.; Bagley, J. Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy with Concurrent Exercise Training: Contrary Evidence for an Interference Effect. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 1029–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, B. The Mechanisms of Muscle Hypertrophy and Their Application to Resistance Training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2010, 24, 2857–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, B. The use of specialized training techniques to maximize muscle hypertrophy. Strength Cond. J. 2011, 33, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, J.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Kikuchi, N.; Nakazato, K. Effects of drop set resistance training on acute stress indicators and long-term muscle hypertrophy and strength. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2018, 58, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, H.; Kubota, A.; Natsume, T.; Loenneke, J.P.; Abe, T.; Machida, S.; Naito, H. Effects of drop sets with resistance training on increases in muscle CSA, strength, and endurance: A pilot study. J. Sports Sci. 2018, 36, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girman, J.C.; Jones, M.T.; Matthews, T.D.; Wood, R.J. Acute effects of a cluster-set protocol on hormonal, metabolic and performance measures in resistance-trained males. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2014, 14, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goto, K.; Ishii, N.; Kizuka, T.; Kraemer, R.R.; Honda, Y.; Takamatsu, K. Hormonal and metabolic responses to slow movement resistance exercise with different durations of concentric and eccentric actions. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2009, 106, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilian, Y.; Engel, F.; Wahl, P.; Achtzehn, S.; Sperlich, B.; Mester, J. Markers of biological stress in response to a single session of high-intensity interval training and high-volume training in young athletes. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2016, 116, 2177–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peake, J.M.; Tan, S.J.; Markworth, J.F.; Broadbent, J.A.; Skinner, T.L.; Cameron-Smith, D. Metabolic and hormonal responses to isoenergetic high-intensity interval exercise and continuous moderate intensity exercise. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 307, E539–E552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahl, P.; Mathes, S.; Achtzehn, S.; Bloch, W.; Mester, J. Active vs. passive recovery during high-intensity training influences hormonal response. Int. J. Sports Med. 2014, 35, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urhausen, A.; Gabriel, H.; Kindermann, W. Blood hormones as markers of training stress and overtraining. Sports Med. 1995, 20, 251–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, B.T.; Herbert, P.; Sculthorpe, N.; Grace, F.M.; Stratton, D.; Hayes, L.D. Lifelong exercise, but not short-term high-intensity interval training, increases GDF11, a marker of successful aging: A preliminary investigation. Physiol. Rep. 2017, 5, e13343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K.S.; Kambadur, R.; Sharma, M.; Smith, H.K. Resistance training alters plasma myostatin but not IGF-1 in healthy men. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2004, 36, 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negaresh, R.; Ranjbar, R.; Habibi, A.; Mokhtarzade, M.; Fokin, A.; Gharibvand, M. The effect of resistance training on quadriceps muscle volume and some growth factors in elderly and young men. Adv. Gerontol. Uspekhi Gerontol. 2017, 30, 880–887. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, M.; Schober-Halper, B.; Oesen, S.; Franzke, B.; Tschan, H.; Bachl, N.; Strasser, E.M.; Quittan, M.; Wagner, K.H.; Wessner, B. Effects of elastic band resistance training and nutritional supplementati on muscle quality and circulating muscle growth and degradation factors of institutionalized elderly women: The Vienna Active Ageing Study (VAAS). Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2016, 116, 885–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, K.; Nagasawa, M.; Yanagisawa, O.; Kizuka, T.; Ishii, N.; Takamatsu, K. Muscular adaptations to combinations of highand low-intensity resistance exercises. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2004, 18, 730–737. [Google Scholar]

- Gotshalk, L.A.; Loebel, C.C.; Nindl, B.C.; Putukian, M.; Sebastianelli, W.; Newton, R.U.; Häkkinen, K.; Kraemer, W.J. Hormonal responses of multiset versus single-set heavy-resistance exercise protocols. Can. J. Appl. Physiol. 1997, 22, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourkioti, F.; Kratsios, P.; Luedde, T.; Song, Y.-H.; Delafontaine, P.; Adami, R.; Parente, V.; Bottinelli, R.; Pasparakis, M.; Rosenthal, N. Targeted ablation of IKK2 improves skeletal muscle strength, maintains mass, and promotes regeneration. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 2945–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenz, T.; Rossi, S.G.; Rotundo, R.L.; Spiegelman, B.M.; Moraes, C.T. Increased muscle PGC-1alpha expression protects from sarcopenia and metabolic disease during aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 20405–20410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilson, H.; Schakman, O.; Kalista, S.; Lause, P.; Tsuchida, K.; Thissen, J.P. Follistatin induces muscle hypertrophy through satellite cell proliferation and inhibition of both myostatin and activin. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 297, E157–E164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, S.; Metter, E.J.; Ferrucci, L.; Roth, S.M. Activin-type II receptor B (ACVR2B) and follistatin haplotype associations with muscle mass and strength in humans. J. Appl. Physiol. 2007, 102, 2142–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, B.; Febbraio, M. Muscles, exercise and obesity: Skeletal muscle as a secretory organ. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2012, 8, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Shafey, N.; Guesnon, M.; Simon, F.; Deprez, E.; Cosette, J.; Stockholm, D.; Scherman, D.; Bigey, P.; Kichler, A. Inhibition of the myostatin/Smad signaling pathway by short decorin-derived peptides. Exp. Cell Res. 2016, 341, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbé, C.; Kalista, S.; Loumaye, A.; Ritvos, O.; Lause, P.; Ferracin, B.; Thissen, J.P. Role of IGF-I in follistatin-induced skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 309, E557–E567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enes, A.; Alves, R.C.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Oneda, G.; Perin, S.C.; Trindade, T.B.; Prestes, J.; Souza-Junior, T.P. Rest-pause and drop-set training elicit similar strength and hypertrophy adaptations compared with traditional sets in resistance-trained males. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 46, 1417–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, J.M.; Kreutzer, A.; Jenke, S.; Phillips, M.D.; Mitchell, J.B.; Jones, M.T. Acute response to cluster sets in trained and untrained men. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2015, 115, 2383–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korak, J.A.; Paquette, M.R.; Brooks, J.; Fuller, D.K.; Coons, J.M. Effect of rest-pause vs. traditional bench press training on muscle strength, electromyography, and lifting volume in randomized trial protocols. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017, 117, 1891–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, M.D.; Rhea, M.R.; Alvar, B.A. Applications of the dose-response for muscular strength development: A review of meta-analytic efficacy and reliability for designing training prescription. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2005, 19, 950–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhea, M.R.; Alvar, B.A.; Burkett, L.N.; Ball, S.D. A meta-analysis to determine the dose response for strength development. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantois, P.; Fonseca, F.D.S.; de Lima-Júnior, D.; Costa, M.D.C.; Costa, B.D.D.V.; Cyrino, E.S.; Fortes, L.D.S. Acute effects of muscle failure and training system (traditional vs. rest-pause) in resistance exercise on countermovement jump performance in trained adults. Isokinet. Exerc. Sci. 2021, 29, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seynnes, O.R.; Boer, M.D.; Narici, M.V. Early skeletal muscle hypertrophy and architectural changes in response to high-intensity resistance training. J. Appl. Physiol. 2007, 102, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammarström, D.; Øfsteng, S.; Koll, L.; Hanestadhaugen, M.; Hollan, I.; Apró, W.; Whist, J.E.; Blomstrand, E.; Rønnestad, B.R.; Ellefsen, S. Benefits of higher resistance-training volume are related to ribosome biogenesis. J. Physiol. 2020, 598, 543–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, V.C.; de Salles, B.F.; Trajano, G.S. Volume for muscle hypertrophy and health outcomes: The most effective variable in resistance training. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atherton, P.J.; Babraj, J.A.; Smith, K.; Singh, J.; Rennie, M.J.; Wackerhage, H. Selective activation of AMPK-PGC-1α or PKB-TSC2-mTOR signaling can explain specific adaptive responses to endurance or resistance training-like electrical muscle stimulation. FASEB J. 2005, 19, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sword, D.O.; Carolina, S. Exercise as a Management Strategy for the Overweight and Obese: Where Does Resistance Exercise Fit in? Strength Cond. J. 2013, 35, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ying, Z.; Bosy-Westphal, A.; Zhang, J.; Heller, M.; Later, W.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Müller, M.J. Evaluation of specific metabolic rates of major organs and tissues: Comparison between men and women. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2011, 23, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allman, B.; Morrissey, M.C.; Kim, J.-S.; Panton, L.B.; Contreras, R.J.; Hickner, R.; Ormsbee, M.J. Fat metabolism and acute resistance exercise in trained women. J. Appl. Physiol. 2019, 126, 739–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niewiadomski, W.; Laskowska, D.; Gąsiorowska, A.; Cybulski, G.; Strasz, A.; Langfort, J. Determination and Prediction of One Repetition Maximum (1RM): Safety Considerations. J. Hum. Kinet. 2008, 19, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbalho, M.; Gentil, P.; Raiol, R.; Del Vecchio, F.B.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Coswig, V.S. High 1RM Tests Reproducibility and Validity are not Dependent on Training Experience, Muscle Group Tested or Strength Level in Older Women. Sports 2018, 6, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapik, J.J.; Staab, J.S.; Harman, E.A. Validity of an anthropometric estimate of thigh muscle cross-sectional area. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1996, 28, 1523–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymsfield, S.B.; McManus, C.; Smith, J.; Stevens, V.; Nixon, D.W. Anthropometric measurement of muscle mass: Revised equations for calculating bone-free arm muscle area. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1982, 3, 680–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988; pp. 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).