2.1. Generation Z’s Consumer Behavior and the Impact of Social Environment

Generation Z represents a transformative demographic segment that is reshaping the landscape of consumer behavior (

Salam et al., 2024). As digital natives, Gen Z individuals have been raised in a world dominated by instant connectivity, mobile technologies, and real-time information exchange (

Kara & Min, 2024). These conditions have not only influenced their attitudes toward consumption but have also redefined the social frameworks within which their behaviors are developed and expressed. Among the most critical forces shaping Gen Z’s consumer decision-making process is the social environment, an expansive and fluid network of peers, communities, digital platforms, and cultural norms that operate as both information sources and behavioral regulators (

Ding & Jiang, 2023). To synthesize the literature, prior studies converge on the idea that Gen Z’s purchasing intentions cannot be understood in isolation but are embedded in a broader social ecosystem. Several constructs consistently emerge across the literature as central to understanding Gen Z’s behavior: social capital bonding, social capital bridging, perceived social pressure, electronic word of mouth (e-WOM), and indirect peer effects. These constructs provide the theoretical and empirical foundation of this study and are further developed in the following subsections. By systematically connecting these constructs to established theories, we clarify how they interrelate and why they form the basis for our hypotheses. One of the most defining characteristics of Gen Z consumers is their socially embedded decision-making (

Bowo & Marthalia, 2024). Unlike previous generations who relied heavily on personal experience, advertising, or expert opinion, Gen Z places substantial value on the opinions, behaviors, and expectations of their social networks (

Harari et al., 2023). This generation views consumption not solely as a means of fulfilling practical needs, but as a mode of self-expression and social signaling (

Theocharis & Tsekouropoulos, 2025). As such, purchase decisions often reflect a desire for social inclusion, identity affirmation, or alignment with perceived peer values. Central to this dynamic is the influence of peer groups, which serve as key referents in the decision-making process (

Djafarova & Foots, 2022). Friends, classmates, online followers, and even acquaintances within digital communities contribute to a continuous stream of feedback, recommendations, and subtle pressures that inform how Gen Z perceives products, brands, and trends (

Kahawandala & Peter, 2020). In many cases, these influences are internalized as normative expectations, leading individuals to favor choices that conform with the preferences and behaviors of their immediate or extended social circle (

Jacobsen & Barnes, 2020). This mechanism is particularly pronounced in contexts involving visible or culturally symbolic products, such as technology, fashion, or lifestyle goods.

The social environment for Gen Z is inherently digital (

Angmo & Mahajan, 2024). Platforms like Instagram, TikTok, Snapchat, and YouTube function not only as entertainment outlets but as powerful ecosystems of influence where consumer identities are shaped and negotiated. These platforms foster communities of interest where like-minded individuals exchange information, experiences, and evaluations (

Dabija et al., 2019). Importantly, these interactions are not passive; Gen Z users are both consumers and content creators, generating reviews, tutorials, unboxing videos, and visual narratives that others use as reference points (

Tata et al., 2023). As a result, the boundary between personal opinion and public influence becomes increasingly blurred, elevating the significance of peer-generated content in shaping consumer attitudes. In this context, electronic word of mouth (e-WOM) emerges as a crucial force (

Masakazu et al., 2025). Gen Z is particularly responsive to e-WOM because it is perceived as authentic, relatable, and credible (

Natalia & Aprillia, 2025). Unlike traditional advertisements, peer reviews and shared experiences carry emotional weight and a sense of trustworthiness that resonate with this generation’s desire for transparency and realness (

Kurnaz & Duman, 2021). Positive e-WOM can rapidly increase interest in a product, while negative e-WOM can damage a brand’s reputation, often irreversibly in a short time span (

Feitosa & Barbosa, 2020). This heightened sensitivity to peer opinion underscores the socially mediated nature of Gen Z’s consumer decisions.

Beyond direct peer influence, indirect social effects also play a significant role. Concepts like “friend of a friend” illustrate how even weak social ties—people with whom one has limited direct interaction—can influence attitudes and behavior through shared content, mutual likes, or algorithm-driven exposure on social platforms (

Kushwaha, 2021). These indirect relationships contribute to what is referred to in theory as social capital bridging, enabling individuals to access diverse opinions and product information that might not circulate within their immediate peer group (

Elkhwesky et al., 2024). This form of influence is particularly effective in introducing Gen Z consumers to new or niche products that are gaining momentum in specific online communities (

Francis & Hoefel, 2018). The impact of social norms and pressures further extends to perceived social pressure, where individuals feel compelled to act in ways that align with the expectations of their network. For Gen Z, this can manifest in trends such as “fear of missing out” (FOMO), which drives them to engage with products, experiences, or content that are gaining popularity among peers (

Deliana et al., 2024). This phenomenon can intensify the urgency to adopt newly launched products, attend particular events, or affiliate with certain brands, not out of personal preference, but out of a perceived need to stay socially relevant (

Serravalle et al., 2022).

Additionally, Gen Z tends to view their consumer identity as a reflection of personal and collective values, such as sustainability, inclusivity, and social responsibility (

Pradhan et al., 2023). These values are often reinforced through their social environment, as peers reward brands and behaviors that align with ethical or progressive ideals (

Dabija et al., 2019). In turn, brands that are perceived as socially tone-deaf or inauthentic can face swift backlash, amplified through rapid peer-to-peer communication and public discourse on social media (

Gomes et al., 2023). In this way, the social environment not only informs preferences but also sets behavioral standards for what is considered acceptable or desirable in consumption. Moreover, the interactivity of Gen Z’s social environment means that the influence process is rarely one-directional (

Ghosh et al., 2024). Peer influence is both given and received, and Gen Z individuals often take on the role of micro-influencers within their own networks (

Kahawandala & Peter, 2020). Their ability to shape the opinions of others, even within a small circle, reinforces a sense of agency and participatory ownership in brand narratives and product communities. This bidirectional influence loop creates a highly dynamic environment in which behaviors and attitudes evolve in response to ongoing social interaction (

Manley et al., 2023). In conclusion, Gen Z’s consumer behavior is deeply embedded within a networked social context where peers, digital communities, and cultural norms collectively shape the ways in which products are evaluated, adopted, and shared. The impact of the social environment is profound, influencing not only the formation of attitudes and intentions but also the emotional and symbolic meaning that consumers attach to their consumption choices (

Angmo & Mahajan, 2024). For marketers and researchers, this underscores the importance of understanding Gen Z not just as individual decision-makers but as socially situated actors, whose behaviors are inseparable from the dynamic and collaborative environments they inhabit.

2.2. Newly Launched Technological Products and Gen Z

The emergence of newly launched technological products, such as smartphones, wearables, AI-driven devices, and smart home solutions, has transformed the landscape of consumer behavior, particularly among Generation Z. This generational cohort represents a digitally native population that has grown up immersed in technology, mobile connectivity, and real-time digital interaction (

Kim et al., 2022). As such, their consumption habits, information-seeking behavior, and decision-making processes differ significantly from those of previous generations (

Theocharis et al., 2025). When it comes to the adoption of new technologies, peer influence and the surrounding social environment play pivotal roles in shaping Gen Z’s attitudes, perceptions, and ultimately their purchasing behavior (

Priporas et al., 2017). Gen Z consumers display a distinctive relationship with technology (

Jaciow & Wolny, 2021). For them, newly released products are not only tools for functionality but also vehicles for social expression, identity building, and group affiliation (

Francis & Hoefel, 2018). The adoption of technological innovations often goes beyond utilitarian motives; it is frequently tied to their need for connectedness, digital fluency, and visibility within their peer networks. As digital natives, Gen Z is not merely passive in their interactions with technology, they actively co-create brand meaning and product value through participation in online communities, content creation, and peer dialogue (

Lee, 2021). What distinguishes Gen Z’s engagement with newly launched products is the immediacy of their responses and their reliance on peer validation. Early adoption is often influenced not just by product features, but by what is seen and shared in social networks (

Cheung et al., 2021). Unboxing videos, peer reviews, influencer content, and social media trends serve as key decision-making tools (

Thangavel et al., 2022). The speed with which this generation processes and reacts to new releases also increases the pressure on brands to continuously innovate and maintain cultural relevance. A product’s “newness” often serves as a social signal, indicating tech-savviness, trend awareness, and group belonging (

Dabija & Lung, 2018).

Moreover, Gen Z places a high value on authenticity and personalization in technological products (

Lamba & Malik, 2022). They are more likely to adopt new technology if it aligns with their personal identity, values, or lifestyle (

Jaciow & Wolny, 2021). For example, a wearable fitness tracker may appeal not just for its functionality but because it signals a health-conscious identity within a social group. Similarly, a smartphone brand may be chosen not solely for technical specs, but because of the narrative it conveys through branding and peer usage. At the same time, digital literacy allows Gen Z to critically assess technological innovations (

Puiu et al., 2022). They actively research, compare, and evaluate new products, while they often turning to peer-generated content rather than traditional advertising (

Dadvari & Do, 2019). This behavior amplifies the role of peer dynamics, as shared experiences, reviews, and recommendations carry more weight when they come from trusted individuals within one’s social circle. The credibility of information is therefore deeply rooted in perceived social proximity rather than brand authority. In essence, newly launched technological products function as both functional tools and social artifacts for Gen Z. Their value is shaped not only by what the product does but by how it is presented, shared, and talked about within digital communities. Peer dynamics play a fundamental role in this process, as adoption becomes a socially negotiated act that reflects and reinforces one’s place within a digitally connected generation.

2.3. Theoretical Background Development and Variable Selection

The study of consumer behavior, particularly among Generation Z and in relation to newly launched technological products, necessitates a thorough understanding of the social, psychological, and marketing mechanisms that influence purchasing intentions. Unlike descriptive accounts, this section provides a structured theoretical synthesis by linking each construct to established frameworks, thereby reinforcing the rationale for our hypotheses. Drawing from established theoretical frameworks—namely Social Capital Theory, Relationship Marketing Theory, the Theory of Reasoned Action, and the Theory of Planned Behavior, the conceptual foundation of the research is built to explain the mechanisms through which social and peer dynamics influence Generation Z’s purchase intentions. These frameworks offer a multidimensional perspective that connects individual attitudes, perceived social norms, relational networks, and behavioral control to consumer decision-making. This synthesis highlights three central mechanisms: (a) social capital bonding and bridging as the relational basis of influence, (b) perceived social pressure and e-WOM as communication and normative channels, and (c) purchase intention as the behavioral outcome shaped by these inputs. Integrating these theories allows us to move beyond fragmented findings and present a more coherent explanatory framework.

Social Capital Theory is rooted in the idea that social networks function as vital resources, facilitating access to information, trust, support, and opportunities through interpersonal and group-based interactions (

Kasim et al., 2022;

H. Zhang et al., 2020). Within this perspective, individuals are not isolated decision-makers but socially embedded actors whose behaviors are shaped by the structures and relationships they participate in. This theoretical lens is particularly relevant in digital environments, where interaction and visibility are integral to consumption behavior. Social capital manifests primarily through two forms (bonding and bridging) each playing a complementary role in shaping consumer perceptions and behavioral intentions. Bonding social capital involves strong, emotionally charged ties among close connections such as family or intimate peers (

Ahmad et al., 2023a;

Hoda et al., 2023). These relationships foster trust and shared values, reinforcing group norms and encouraging behaviors such as brand loyalty and repeated purchases. For Generation Z consumers, the influence of close peer networks is significant. When new technological products are endorsed within these circles, the likelihood of adoption increases due to emotional alignment and social belonging (

Pang et al., 2021;

Radaelli et al., 2024).

Bridging social capital, on the other hand, refers to weaker, more diverse ties that span social, demographic, or interest-based boundaries (

Dhar et al., 2024;

Perry et al., 2022). These connections enable access to new ideas, perspectives, and innovations. In digital consumer spaces, this form of capital is often activated through interactions with influencers, brand communities, or acquaintances on social media. It fosters discovery and curiosity, particularly relevant to the adoption of novel technological products that thrive on early exposure and trend diffusion (

Kalra et al., 2021;

Yuan et al., 2021). The co-existence of bonding and bridging ties generates a dynamic consumer ecosystem where trust and familiarity intersect with novelty and expansion. Consumers, especially from Gen Z, navigate between intimate peer influence and broader online discourse, leveraging both emotional support and informational diversity to shape their decisions (

Degli Antoni & Grimalda, 2024). Participation in digital brand communities is one manifestation of this dual social structure. Users engage with peer-generated content, shared identity, and interactive discussions not only to gather information but also to affirm their place within the group (

Munawar & Siddiqui, 2020;

Jeong et al., 2021). Activities such as writing reviews, posting branded content, or commenting on product experiences become expressions of social capital, driven by mutual trust and relational investment (

Li et al., 2024). This behavior frequently takes the form of electronic word of mouth (e-WOM), an informal communication process that carries substantial weight in digital decision-making environments (

Levy et al., 2024). Building on the foundation of social capital, perceived social pressure emerges as a more individualized mechanism through which social expectations influence behavior. It refers to the internalized sense of what others expect and accept, shaping one’s choices within their immediate or extended network (

Simons et al., 2021;

Dhar & Bose, 2023). For Generation Z, who are highly active in social media and attuned to peer dynamics, this influence is especially salient. The pressure to adopt popular brands, stay up to date with new tech, or conform to group standards is often magnified by online exposure and algorithm-driven visibility (

Gani et al., 2024;

Salazar et al., 2013;

Luo et al., 2020). The phenomenon becomes evident when individuals purchase products, such as new smartphone models or wearable devices, not solely for their functionality but to align with perceived group norms or avoid social exclusion (

Hu et al., 2019).

The Theory of Planned Behavior conceptualizes perceived social pressure—termed subjective norms—as a core predictor of behavioral intentions (

Bastian et al., 2017). Reference groups including peers, family, and digital communities influence individual behavior, particularly when those groups are perceived as trustworthy or influential (

Khare, 2023). This pressure arises from both interpersonal sources (e.g., direct peer recommendations) and external sources (e.g., media endorsements, influencer opinions) (

Wolske et al., 2020). Contextual strength also plays a role. In clearly defined situations—such as the anticipation of peer scrutiny—individuals are more likely to conform. In more ambiguous situations, social pressure may act more subtly, but still guides behavior in identity-related consumption contexts (

Exline et al., 2012;

Singh et al., 2020). For Generation Z, navigating this balance often leads to purchases influenced by group alignment rather than personal need alone (

Yang et al., 2021). Electronic word of mouth adds another layer to this dynamic, functioning as both a communication mechanism and a relational expression. It involves user-generated, informal content such as reviews, testimonials, or posts about products and services shared on social platforms or review sites (

Chatzipanagiotou et al., 2023;

Kusawat & Teerakapibal, 2024). This communication is not constrained by geography or time, making it especially powerful for Gen Z consumers who actively engage with online content before making purchase decisions (

Bu et al., 2021;

Sharma et al., 2024). e-WOM draws strength from both bonding and bridging social capital. Trusted peers enhance group cohesion and loyalty, while broader networks foster awareness and trial behavior for lesser-known products or emerging brands (

Ahmad et al., 2023b;

Yuan et al., 2021).

Relationship Marketing Theory complements this view by interpreting e-WOM as a channel through which relational trust and brand commitment are built over time (

Le & Ryu, 2023). Positive experiences shared online not only strengthen consumer–brand bonds but also influence wider audience perceptions. The credibility and tone of user reviews, along with their volume and perceived usefulness, are crucial determinants of consumer trust and decision-making (

Akoglu & Ozbek, 2024;

Hanks et al., 2024;

D’Acunto et al., 2023). For Generation Z, the act of engaging with such content is not only informational but performative, reinforcing their identity within digital communities and shaping their social presence (

Leong et al., 2022;

Ngo et al., 2024). The notion of the “friend of a friend” offers a compelling extension of this logic. While lacking direct interpersonal ties, these connections often exert meaningful influence through perceived credibility and shared network context (

Jackson & Rogers, 2007;

Lin et al., 2023). This type of indirect influence aligns with bridging social capital and is particularly influential in e-WOM settings, where information shared by a mutual acquaintance carries more weight than an anonymous source (

Tajvidi et al., 2020). Such dynamics are further amplified on platforms that encourage visible interaction (likes, comments, shares) enabling peer influence to travel across extended networks in what has been termed “social ripple effects” (

Goodreau et al., 2009). This facilitates viral dissemination of product endorsements and brand experiences, often leading to behavioral alignment even without direct contact between original sender and final receiver (

Montgomery et al., 2020;

Rossini et al., 2021). Brands that successfully activate these extended ties can dramatically increase their reach, credibility, and impact within Generation Z audiences (

Aichner et al., 2021;

Muliadi et al., 2024).

To understand the underlying decision-making process, psychological models such as the Theory of Reasoned Action provide further depth. According to this theory, behavior is driven by intention, which in turn is shaped by both individual attitudes and perceived social norms (

Ajzen & Kruglanski, 2019;

Mital et al., 2018). In the case of Gen Z consumers, favorable attitudes toward a product combined with strong peer endorsement increase the likelihood of purchase. The Theory of Planned Behavior expands on this by adding perceived behavioral control, whether the individual believes they can perform the behavior given potential constraints (

Ajzen, 1991;

Ajzen & Schmidt, 2020). These models highlight that even when social and personal factors align, actual behavior is moderated by access to resources, situational confidence, and capability. In light of these frameworks, purchase intention emerges as the key outcome variable—shaped by social capital, perceived social pressure, and the dynamics of e-WOM and indirect peer influence. These interconnected factors provide a comprehensive explanation of Generation Z’s consumption patterns in a digitally mediated environment, particularly when it comes to the adoption of newly introduced technological products. Rather than being isolated drivers, each component contributes to a multifaceted ecosystem where decision-making is continuously shaped by social interaction, relational cues, and psychological expectations. The relationship between these variables and their theoretical underpinnings is summarized in the following

Table 1.

The integration of these variables creates a robust model for examining the behavior of Gen Z consumers in the context of newly introduced technological products. The theoretical background provides clear justification for exploring the role of both direct and indirect social influences, marketing relationships, and psychological drivers in shaping consumer intention.

2.4. Product Type as a Moderator in the Relationship Between Social and Peer Influences and Purchase Intention

Consumers make countless decisions on a daily basis, which has sparked interest in studying consumer behavior, the motivations behind certain choices, and the factors that influence them—as is the case in this dissertation. In general, it has been found that the level of involvement mentally triggered before the consumption of different products or brands varies, and as a result, products have been classified into two categories: high-involvement and low-involvement products (

Abdel Wahab et al., 2023). Low-involvement products refer to items purchased more frequently, with little effort, and often impulsively, while high-involvement products require more time investment and information search prior to selection (

Liu & Yu, 2024). To clarify, examples of low-involvement products include food items, whereas laptops can be considered high-involvement products (

Wang et al., 2023). Nevertheless, each generation, with its unique characteristics, may redefine such classifications. According to

Y. Zhang et al. (

2024), purchases of low-involvement products are often based on heuristic choices or mental shortcuts such as familiarity, recommendations, or optimal pricing. In contrast, high-involvement products are often purchased to support an individual’s image or self-perception (

Lim et al., 2023).

R. Kumar et al. (

2023) viewed involvement as a goal-directed motivation that indicates how personally relevant a product is to the consumer, based on how well it reflects their self-concept (

Palla et al., 2023). However, the level of consumer involvement in a particular product category or brand may vary, as the drivers of involvement differ (

Stokburger-Sauer et al., 2012).

Regarding the categorization of products based on involvement, there is disagreement about which product categories are most capable of engaging consumers (

Tassiello et al., 2021). Specifically, most researchers have argued that it is easier to engage consumers with high-involvement products, as consumers tend to connect with and form emotional attachments to these products to a greater extent (

H. Kumar & Srivastava, 2022). However,

Gong et al. (

2023) contend that a high level of involvement is not limited exclusively to high-involvement products. As

Y. Zhang et al. (

2024) conclude, low-involvement products are rarely explored and are merely suggested for future research, resulting in a lack of knowledge about their potential to generate consumer involvement. The level of involvement, in general, is influenced by three categories of factors: personal, situational, and physical (

Palla et al., 2023). First, the personal factor refers to the consumer’s inherent value system and needs that motivate them to purchase a product (

Wang et al., 2023). The situational factor relates to circumstances that temporarily increase the importance and interest in a product. Lastly, the physical factor refers to differences in the product’s characteristics that stimulate interest (

Loureiro et al., 2023). Involvement can affect consumer behavior and is linked to personal relevance, interest, and the consumer’s level of motivation (

Lim et al., 2023). Therefore, it can be said that product involvement is a complex concept positioned between consumers and their behavior, and it can influence the purchasing decision-making process (

Xu et al., 2023).

A key category for technological products, particularly due to the high price of some of them, is their classification as luxury goods. The fundamental idea behind this approach is that for a product or brand to be classified as luxury, it must be associated with certain characteristics such as high quality, high price, superior performance, and authenticity (

Chan & Northey, 2021).

Shankar and Jain (

2021) link luxury with selective or limited distribution, brand image association, and extreme evaluations of quality and price. This definition aligns with that of

Jain (

2022), who states that luxury refers to products that meet the highest standards within a product category. An alternative approach is offered by

Aycock et al. (

2023), who consider luxury as part of a continuum in which consumers determine where the ordinary ends and where prestige begins. Products are perceived as prestigious because they possess certain features, many of which are linked to luxury (

F. Yu & Zheng, 2022). Prestige products must offer ultimate quality and value, be distributed in a limited way, and be available only to consumers willing to pay a high price (

Fazeli et al., 2020).

Jain (

2021) argues that luxury brands are associated with high price, quality, esthetics, rarity, and specialization. Additionally,

Aprillia et al. (

2019) note that the foundation of luxury consumption lies in innovation and culture, alongside quality and high price. According to

Guzzetti et al. (

2021), luxury brands are most commonly identified by features such as high quality, price, rarity, prestige, and authenticity, while also incorporating non-necessity and the provision of symbolic and emotional value. Finally, price plays a decisive role in the definition of luxury (

S. Yu et al., 2018). For example, a high price is often perceived as inherently linked to luxury, with this perception based either on the product’s absolute value or in comparison to other luxury or non-luxury products (

Xu et al., 2023). Luxury products or services are typically expensive, both in absolute and relative terms (

Aycock et al., 2023).

2.5. Hypotheses Development

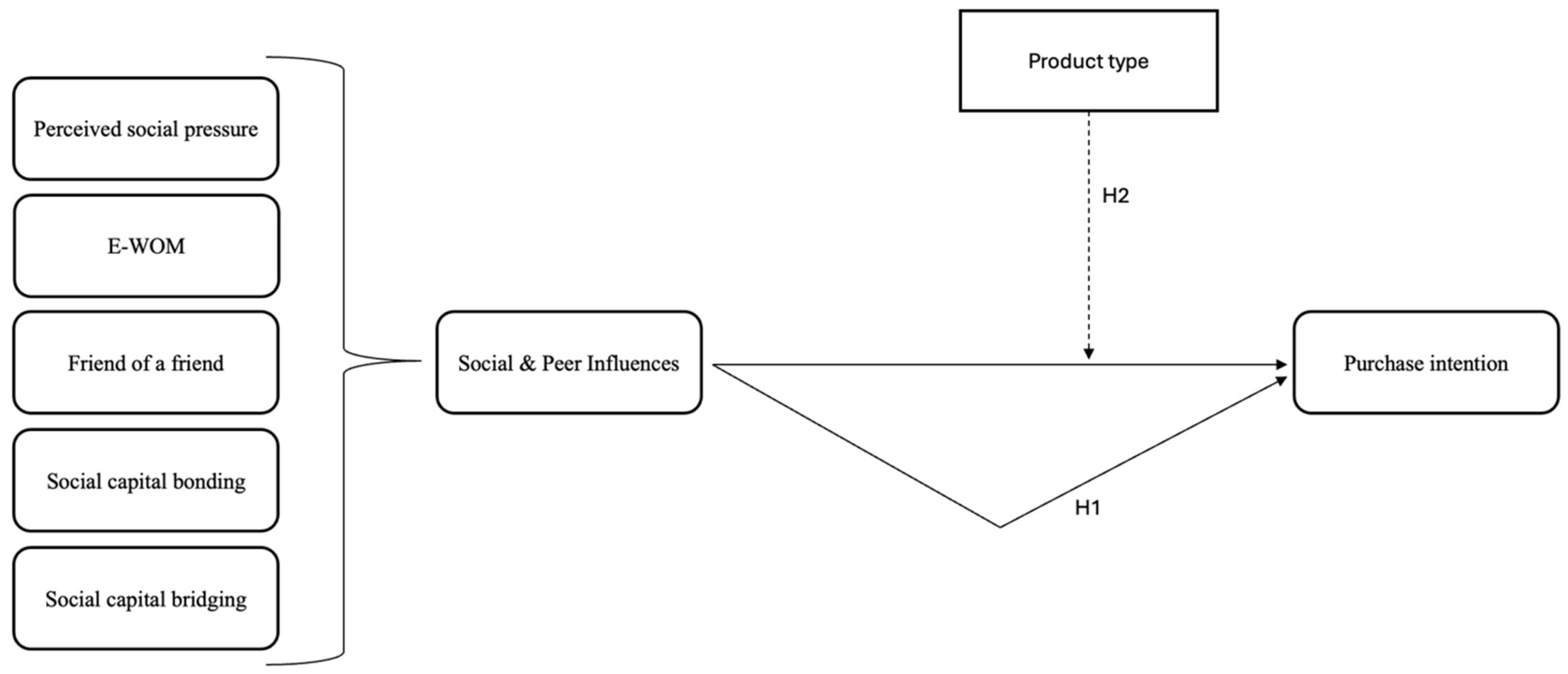

Based on the above theoretical synthesis, we explicitly formulate the study’s hypotheses. The first hypothesis is grounded in Social Capital Theory, Relationship Marketing Theory, and the Theory of Planned Behavior, which collectively predict that peer dynamics and social mechanisms will directly affect Gen Z’s purchasing intentions.

H1. Social and peer influences positively affect the purchase intention of Gen Z regarding newly launched technological products.

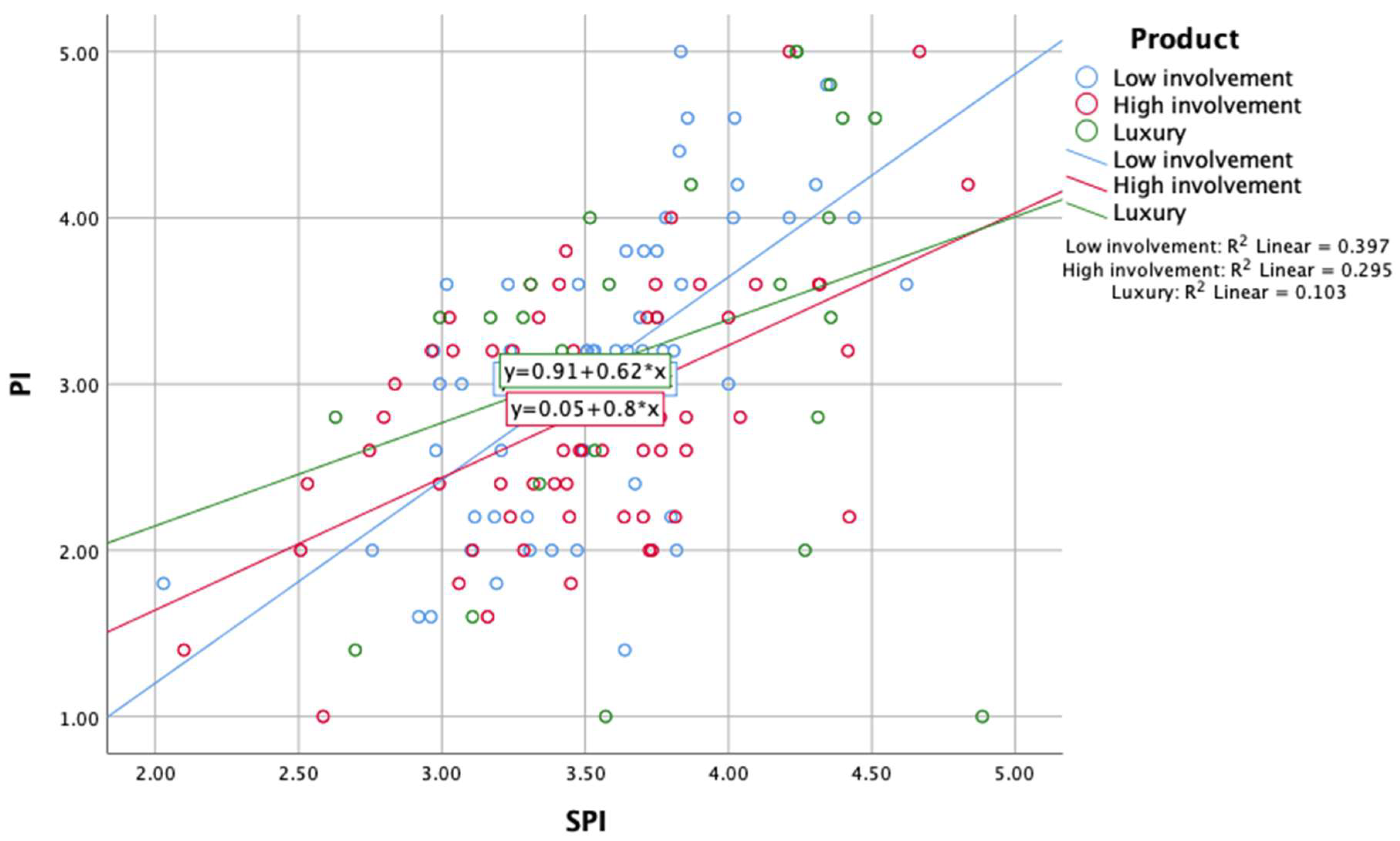

The second hypothesis builds on product involvement and luxury consumption literature, suggesting that product type may alter the strength of social influence on purchasing behavior.

H2. Product type moderates the relationship between social and peer influences and purchase intention of Gen Z regarding newly launched technological products.

While H1 establishes the fundamental relationship between social and peer influences and purchase intention, it is equally important to recognize that this relationship may not be uniform across all product types. This consideration is addressed through H2. Specifically, product type may significantly alter the strength or direction of social influence on Gen Z’s intention to purchase. For instance, the influence of peers may be more pronounced when it comes to low or high involvement products (

Ajzen, 2020;

N. Kumar et al., 2022). By testing the moderating role of product type, H2 seeks to refine our understanding of how contextual factors shape the social dynamics of consumer decision-making and offers a more nuanced application of the theoretical model presented in

Figure 1. Together, H1 and H2 provide a theoretically grounded model that clarifies how social and peer dynamics operate as antecedents of purchase intention, while product type functions as a contextual moderator. This structuring reinforces the literature review by moving from synthesis to testable hypotheses, thereby addressing both theoretical reasoning and empirical focus.