Abstract

This study explores the unique realm of women’s entrepreneurial leadership within Stewart’s role demands-constraint-choice in Greece. This brings to light the underrepresented role of women entrepreneurs in the country and sets out to fill the literature gap by exploring their distinct motivations and leadership. By employing a qualitative method and conducting semi-structured interviews with Greek women entrepreneurs, this study uncovers a complex web of motivations intertwined with personal goals, sociocultural norms, and economic conditions that diverge from those in other advanced economies. Notable motivations include financial autonomy, family support, societal betterment, and personal fulfillment. The findings also provide a comprehensive understanding of the intricate interplay between entrepreneurs’ roles, motivations, and leadership decisions within socioeconomic and cultural contexts. This research enriches the broader discourse on international entrepreneurship and women’s studies, deepening our understanding of Greek women’s entrepreneurship. The practical implications of these findings offer strategies for policymakers, educators, and industry professionals to foster an environment that supports women’s entrepreneurial leadership in Greece and other emerging economies.

1. Introduction

The development of women entrepreneurs worldwide is more than a narrative of business creation; it is a story of resilience, innovation, and significant societal transformation. In the 21st century, women are reshaping the entrepreneurship landscape, redefining traditional notions of professional success in a complex, multitasking environment with digital integration. Globally, women entrepreneurs are recognized as substantial economic contributors (; ; ).

In this study, an entrepreneur is defined as an individual who initiates, organizes, and operates a business venture, taking on greater than-normal financial risk. Entrepreneurs are often seen as innovators who develop new, efficient methods and products that contribute to the economy through job creation and market competition (; ). The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) describes entrepreneurs as individuals who play a pivotal role in economic development by introducing innovations and driving employment growth, emphasizing the evolving nature of entrepreneurship in the face of global challenges, including technological advancements and sustainability concerns (; ).

The role of women as entrepreneurs is not just a matter of economic necessity but also a cornerstone of robust economic development. The () underscores the substantial contribution of women-led businesses to employment and wealth creation, a sentiment echoed by other scholars (; ). The United Nations Development Programme () observes that women-led businesses are more likely to reinvest their profits into their communities, thus bolstering social welfare. These organizations and scholars recognize that women entrepreneurs bring unique products and services, fostering innovation and diversity in the marketplace.

Despite navigating the demanding milieu of multitasking between family, business demands, and social and business constraints, they are challenging traditional business norms despite having a lack of resources, mainly access to finances. Researchers have highlighted how women balance multiple roles and redefine their success beyond conventional metrics. Despite this progress, traditional barriers persist (; ; ; ). There are persistent challenges, including multitasking demands, constraints, unavoidable choices that must be made, and restricted access to essential resources (; ; ; ) as well as restrictions arising from gender norms () and/or from the absence of the rule of law which women find difficult to deal with ().

Additionally, the perpetuation of the glass ceiling in various sectors is evident in research (; ; ), illustrating that women’s entry into traditionally male-dominated domains has not entirely dismantled systemic barriers. Other scholars (; ) have underscored that women struggle to access limited financial resources, marketing expertise, and support services, including business networks and digital technology. The () underscores the substantial contribution of women-led businesses to employment and wealth creation, a sentiment echoed by other scholars (; ; ). The United Nations Development Programme () observes that women-led businesses are more likely to reinvest their profits in their communities, thus bolstering social welfare. These organizations and scholars recognize that women entrepreneurs bring unique products and services, fostering innovation and diversity in the marketplace.

In an era of digital business transformation, women entrepreneurs face another challenge akin to their male counterparts: specific skills that are imperative for entrepreneurial success. The () reports that digital literacy and innovation are critical for entrepreneurs. Such skills are significant for women entrepreneurs, recognizing the existence of subtle yet impactful deterrents to their entrepreneurial activities, which stem from the challenges and barriers they face, whether as IT professionals or entrepreneurs in the digital technology sector, especially considering the gender-biased nature of existing entrepreneurship research and the noted underrepresentation and theoretical oversight of gender in entrepreneurship.

Restricted women entrepreneurship is recorded in both developing and developed countries. One of the developing countries in which this is true is Greece. Gender inequality, not only regarding entrepreneurial activity, is a lingering issue in Greece, which adds complexity to assuming entrepreneurial leadership. The role of women entrepreneurs in Greece extends beyond mere economic contributions; they are vital agents of innovation and social change. This paper aims to understand the performance of those Greek women who became entrepreneurs by analyzing their behavior using Stewart’s demand, constraints, and choices (DCC) framework. This understanding can lead to the development of effective policies to support these women entrepreneurs.

However, there are gaps in the extant literature on women entrepreneurs in Greece. A notable dearth of comprehensive research has focused on specific demands, constraints, and choices (DCC). Gender disparities in entrepreneurship often receive scant research attention, which is exacerbated in countries with economic austerity (; , ). This lack of focused research impedes the development of effective policies to support these women entrepreneurs. Gender inequality, a lingering issue in Greece, adds complexity to these challenges. The role of women entrepreneurs in Greece extends beyond mere economic contributions, as they are vital agents of innovation and social change.

This research aims to systematically explore and elucidate the complex motivations, challenges, and leadership dynamics of women entrepreneurs in Greece. Through a qualitative analysis of semi-structured interviews with these entrepreneurs, the study seeks to uncover how personal goals, sociocultural norms, and economic conditions uniquely influence their entrepreneurial journeys compared to other advanced economies. The primary objectives are to identify the key drivers of entrepreneurship among Greek women, the barriers they face within the socio-economic framework, and how these factors influence their leadership styles and business strategies. By addressing these aspects, the research intends to contribute to the broader discourse on international entrepreneurship and gender studies, offering insights that can inform targeted policy reforms and support mechanisms to enhance the entrepreneurial ecosystem for women in Greece and similar socio-economic environments.

This study adopts a discovery-oriented approach, intentionally designed to explore the multifaceted phenomena of women’s entrepreneurship in Greece without the constraints of pre-defined hypotheses. This methodological choice is predicated on the recognition that the entrepreneurial landscape for women in Greece is underexplored, and that the existing literature may not adequately capture these entrepreneurs’ unique challenges and motivations. By employing an exploratory framework, this research aims to generate a grounded understanding of the complex interplay between personal goals, sociocultural influences, and economic factors, allowing for the emergence of new insights and patterns. This approach is particularly suited to this study’s aim to inform policy by uncovering nuanced realities and providing a rich, empirical basis for developing targeted interventions. Furthermore, this research builds upon the prior work of one of the authors on women entrepreneurs in Kazakhstan (). It complements an ongoing investigation in Ireland focused on the same topic. The ultimate objective of the lead researcher is to undertake a multi-country comparative analysis, addressing a significant gap in the existing literature on women’s entrepreneurial ecosystems across diverse sociocultural contexts. Such comparative studies are sparse, yet they hold the potential to uncover critical insights into the nuanced challenges and opportunities that women entrepreneurs face in varying national environments. Preliminary results for the ongoing research in Ireland are available at https://hdl.handle.net/2144/48678 (accessed on 4 August 2024). Efforts to address these challenges, as well as policy interventions to promote gender equality in entrepreneurship, mentorship programs, and initiatives to increase access to financing and resources for women-led businesses, exist (; ; ). Similarly, further research on Greek women entrepreneurs’ challenges regarding role demands, constraints, and choices is critical for several reasons. Like many similar economies, Greece has witnessed a growing interest in promoting women’s entrepreneurship through economic empowerment and gender equality (; ; ; ; ). However, Greece’s unique sociocultural and economic context, influenced by traditional gender roles and economic fluctuations, demands a nuanced understanding of Greek women entrepreneurs’ challenges (; ). The scarcity of research on their unique needs and challenges, particularly in the face of gender inequality, remains a glaring gap.

Investigating these challenges can inform targeted policy interventions and support mechanisms tailored to the Greek context, thereby fostering an environment conducive to women’s success as entrepreneurs. Moreover, given the significance of entrepreneurship in economic recovery and development, particularly in post-crisis Greece, shedding light on the DCC issues faced by Greek women entrepreneurs is crucial for harnessing the untapped potential of this demographic and contributing to sustainable economic growth in the country.

This study explores the evolving roles of women entrepreneurs and the persistent barriers they face, delving into the lives and challenges of women entrepreneurs in Greece, a group whose significance is often overshadowed by broader economic narratives. With their diverse approaches to DCC, these women entrepreneurs stand at the crossroads of gender inequality and economic revitalization. However, their impact in Greece is particularly profound, although insufficiently explored, in the unique tapestry of the country’s economic and social landscape. This study seeks to bridge this gap through targeted research and policy recommendations to harness the potential of women entrepreneurs in Greece.

This study examines women’s entrepreneurial leadership in Greece. It establishes a foundation by providing an introduction that places the study in the context of entrepreneurship and gender studies, emphasizing the research goals and unique features of the Greek environment. The literature review section summarizes previous studies, discusses their theoretical foundations, and pinpoints the areas the study seeks to address. The methodology section outlines the qualitative approach, explaining the data gathering and analysis methods that support the study’s empirical findings. The findings section details the results and analysis of the research and examines how they enhance the comprehension of women entrepreneurs’ drives and decision-making patterns in Greece. Discourse combines these perspectives with existing research to explain the consequences of theory and application. In the conclusion section, the paper outlines the main contributions, recognizes the limitations, and proposes directions for future research, thus demonstrating the importance of the study for both the academic and practical aspects of women’s entrepreneurship.

2. Literature Review

New studies indicate that women participate in entrepreneurship in unique ways compared with men, revealing similar trends (; ; ; ; ; ). Women business owners launch enterprises for various purposes, such as breaking free from poverty and achieving autonomy (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ). A recurring discovery is that women frequently begin their businesses to balance work and personal life and have more influence over their schedules (; ; ; ). Women are also more inclined to launch businesses in industries that reflect their beliefs, such as social or environmental issues than men (; ; ; ; ). Nevertheless, women entrepreneurs continue to require assistance with significant obstacles, such as restricted financing and connections, which can impede their development and accomplishments (; ).

It is crucial to emphasize that the percentage of women employees is higher in industries with low productivity, profitability, and growth potential than in those with more men (; ). This disparity is not just a statistic but a pressing issue that needs to be addressed. On a global scale, women entrepreneurs have fewer income prospects than men. Women’s participation in the workforce is lower than men’s; when employed, they typically receive lower pay and are more inclined to participate in less lucrative activities than men. On average, women-led companies display inferior economic results, with reduced dimensions, decreased profitability, and slower progression rates (; ; ). Nonetheless, some recent evidence from low- and medium-income countries suggests that female management and female ownership can positively impact access to finance (see, for example, ). The main reason for these variations in economic results is the separation of sectors, with women typically working in the retail, small businesses, and specific service industries. It is imperative to recognize the importance of gender diversity in industries and take steps to address these issues.

With poverty prevalent in many parts of the world, researchers must explore what encourages individuals to start and maintain businesses to improve their living standards. In emerging markets, women frequently see entrepreneurship as the primary option for securing employment (). Women entrepreneurs may face obstacles due to prejudice or preconceived notions based on gender, affecting their image in the eyes of investors, clients, and other parties (; ). Nevertheless, despite these obstacles, women’s entrepreneurship has the potential to contribute substantially to the economic growth of these nations. Factors like the drive to generate income, achieve autonomy, and foster personal growth motivate women to pursue entrepreneurship (; ; ).

According to the (), () report, the motivations driving women to start businesses differ across countries and can be influenced by the scale of the business. Women entrepreneurs frequently encounter numerous challenges, including limited access to finance, constrained market opportunities, and insufficient social support (; ; ; ). Research indicates that married women with young children are more likely to establish businesses than seek traditional employment (; ; ). This tendency is often driven by financial necessity, a push factor, which may also encompass a desire for a better work-life balance and dissatisfaction with previous employment (; ; ). However, studies suggest that push and pull factors motivate women entrepreneurs in developed and developing nations (; ; ).

Women entrepreneurs contribute to economic growth through business establishments and maintenance. The () data, as depicted in Table 1, offers a comprehensive view of entrepreneurial activities across various European countries, including Greece, North America, and Israel. It provides a valuable resource for understanding the entrepreneurial landscape in these regions compared with Greece.

Table 1.

Greece’s entrepreneurial activity is comparable to that of European countries, the U.S., Canada, and Israel. (SOURCE: Adapted by the authors from ’s () report data.

Table 1 summarizes Greece’s position relative to countries with higher entrepreneurship activity.

- Aspiring Entrepreneurs: In Greece, 10.9% of adults were identified as aspiring entrepreneurs, which is lower than the European average of 14.4%. Countries such as Croatia (27.9%) and Latvia (24.6%) showed significantly higher percentages, suggesting a more vibrant entrepreneurial intent among the adult population.

- Nascent Entrepreneurs: Greece’s percentage of nascent entrepreneurs is 3.2%, which is lower than the European average of 5.3%. Countries such as Sweden (6.1%) and Italy (5.3%) have higher proportions, indicating greater entrepreneurial activity.

- New Business Owners: At 2.4%, Greece’s new business owner percentage is below the European average of 3.3%. This suggests a relatively lower transition rate from aspiring to actual business ownership than that in other European countries.

- Early-stage entrepreneurs (TEA): Greece’s TEA rate is 5.5%, which is below the European average of 8.4%. This indicates that the overall environment in Greece may be less conducive to entrepreneurship or that fewer individuals progress from nascent to early-stage entrepreneurship.

- Owner-Managers: Greece stands out, with 14.7% of adults being owner-managers, significantly higher than the European average of 6.8%. This suggests a relatively high level of small business or self-employment activity, which may reflect necessity-driven entrepreneurship due to the economic factors in Greece.

While Greece shows a higher proportion of owner-managers, it lags significantly in nascent, new business, and early-stage entrepreneurial activities compared to European countries with more vibrant entrepreneurial ecosystems. This stark contrast highlights potential areas for policy intervention to foster a more supportive environment for new entrepreneurial ventures in Greece.

There is a notable lack of comprehensive studies on women entrepreneurs in emerging and advanced economies, including Greece, who exhibit entrepreneurial leadership and are motivated by innovation and opportunities (; ; ). Most existing research centers on women entrepreneurs from community-based or disadvantaged groups. Nonetheless, studies have identified common traits among women entrepreneurs, such as a tendency towards risk aversion, difficulties in securing substantial financial resources, varying levels of motivation and education, the drive to start businesses, access to decision-making support, and effective use of networks (; ). Investigating women’s entrepreneurship in Greece could provide significant insights into this field by highlighting the importance of contextual factors as critical analytical elements.

2.1. Women and Entrepreneurial Leadership

Inadequate recognition of the nexus between entrepreneurship and leadership has significantly shaped the study and depiction of gender in entrepreneurship research. Many scholars have engaged in discourse on the interplay between gender and entrepreneurship, often presenting femininity and entrepreneurship as opposing constructs deeply embedded in entrepreneurial identity (; ). Moreover, the public’s perception often links successful entrepreneurship with masculine traits, leading to an incomplete comprehension of the field (; ).

In this study, entrepreneurial leadership is defined as the process of identifying opportunities and driving business ventures to achieve transformational progress within dynamic and uncertain market environments (; ). It combines traditional leadership functions, including vision formulation and team motivation, with entrepreneurship’s innovative, risk-taking spirit. This leadership style is not confined to startup scenarios but applies to corporate settings where leaders harness opportunities for innovation and growth.

In the context of women entrepreneurs, this definition expands to include the specific challenges and opportunities women leaders face. Women entrepreneurs often navigate additional layers of complexity, such as balancing gender expectations and overcoming institutional and cultural barriers that disproportionately affect their leadership and entrepreneurial activities. Entrepreneurial leadership among women frequently involves business innovation, advocacy, and change management that challenge the status quo and foster inclusivity in the business ecosystem. This dual focus underscores women’s entrepreneurial leadership as both a catalyst for business innovation and a transformative force for societal and cultural shifts within and beyond the marketplace (; ; ).

Entrepreneurial leadership plays a vital role in the success of businesses by promoting creative thinking, taking risks, and motivating others toward a common goal (; ). As per the 2022 report from the GEM, entrepreneurial leadership is vital for fostering innovative, high-growth companies and aiding job growth and economic advancement. Entrepreneurial leaders possess a unique talent for identifying and exploiting market opportunities. They frequently deeply comprehend what customers require and can promptly modify their offerings to meet these requirements (; ). Consequently, they frequently lead to pioneering new and emerging markets. They are recognized for their strong commitment to social and environmental responsibility and are motivated to establish enterprises that positively influence society. This is crucial in the current climate, in which consumers are more interested in sustainable and socially responsible businesses (; ; ; ).

The lack of awareness of the intersection of entrepreneurship and leadership has significantly impacted how gender is examined and expressed in entrepreneurship research. Many researchers have developed arguments about entrepreneurship and gender, often portraying womanhood and entrepreneurship as opposing discourses based on the perspective of entrepreneurial identity (; ). Some researchers have also noted that public opinion is typically associated with successful entrepreneurship with male qualities rather than women qualities, leading to an incomplete understanding of the field (; ). Women frequently act as influential role models, shaping and conveying collective expectations, incentives, and responsibilities (), which fosters a positive organizational climate (; ). Their presence promotes creativity and innovation (; ), teamwork (), and continuous learning and collaboration (; ; ).

2.1.1. Women’s Leadership Behavior in Startups

The existing literature delves into the gendered nature of leadership roles. It highlights how culturally constructed expectations of women’s behaviors and attitudes have institutionalized organizational gender distinctions (). Women leaders and entrepreneurs navigate and counteract these expectations in their leadership roles (). While individual-level characteristics are recognized as the primary enablers of entrepreneurship, little research explains how individuals make themselves influential leaders, and the context plays a crucial role in shaping perceptions of effective leadership ().

Traditional views emphasize personal attributes as primary determinants in examining entrepreneurship, especially in startups. However, recent research has underscored the importance of gender in understanding leadership and entrepreneurship dynamics (; ; ). These studies suggest that contextual influences such as societal norms, organizational culture, and industry expectations are critical in shaping perceptions of effective leadership.

Further research is needed to explore how women entrepreneurs can develop leadership skills within entrepreneurial ventures and how they can develop leadership skills (). Leadership roles often emerge through context-driven communication amid significant changes, necessitating support from various stakeholders and alignment with environmental frameworks. Role perceptions are influenced by the demands and constraints placed on individuals, which affect their discretionary choices in these roles (; ).

Discretion within a role hinges on an individual’s perceived capabilities and ability to shape their responsibilities and boundaries (; ). Thus, leadership encompasses multiple facets, including attitudes toward content, structure, function, and overarching social context. Both individual and situational factors significantly influence the decision-making processes at all levels (; ). Despite extensive research, there is still a need for comprehensive models, which are holistic frameworks that consider all relevant individual and contextual factors in assessing leadership effectiveness, particularly concerning women entrepreneurs.

2.1.2. Women’s Entrepreneurial Context in Greece

The women’s participation rate in the Greek labor market declined from the 1960s until the beginning of the 1990s, as the number of women who worked in the agricultural sector decreased following the sector’s contraction. Since the 1990s, women’s participation in the labor market has increased following the expansion of the public sector and the need for two sources of income per household. Despite the increase in women’s participation rate in the labor market, this is still low, about 48% in Q1-2024 for women over 25 years old (), compared to other high-income economies, including most EU member states. Women have a very high unemployment rate and, when employed, usually work in low- and medium-skilled jobs rather than in management positions (; ). On average, from 2006 to 2020, the percentage of women employed in management positions (either as entrepreneurs or as dependent employees) in the non-farm private sector stood at 6%, compared to over 10% for men. More women than men worked as dependent employees. On average, from 2006 to 2020, 70.6% of women worked as dependent employees, while the percentage for men was 59.5%. The proportion of self-employed employees, entrepreneurs in the sense used in this study, stood at 12.7% for men and 6% for women. According to the General Commercial Register of all active companies in Greece, known as GEMI, men are involved in some managerial/ownership roles in 70.6% of companies registered with GEMI, with women being involved in the remaining 29.4% ().

Women’s entrepreneurship in Greece is mainly of the necessity type more than it is for men () and is increasingly characterized by involvement in agro-food, tourism, and creative industries, leveraging local traditions and cultural heritage to foster business growth () and is primarily involved in business-to-consumer activities (). The ICAP-CRIF report on women’s entrepreneurship in Greece for 2022 shows that women will lead the most in micro and small enterprises (). The importance of women’s entrepreneurial roles has emerged in the literature because entrepreneurship is recognized as a significant tool for improving employability. Entrepreneurship provides a domain for women to build and sustain their economic empowerment by developing skills, finding jobs, working flexibly, achieving work–life balance, and generating income. Entrepreneurship, leadership, and networking impact women’s venture performance but not without challenges (; ).

Greek women entrepreneurs have emerged as particularly pivotal figures. Despite numerous economic challenges, including the impact of the financial crisis, these women have developed small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and have emerged as leaders (; ; ). In Greece, women-led businesses play a crucial role in spurring economic recovery, especially in critical sectors, such as tourism, retail, and services (; ; ). Pivotal challenges include balancing familial responsibilities with business demands, often exacerbated by traditional gender roles that influence women’s business participation and entrepreneurial identity. Networks and digital competencies also play crucial roles, with e-skills being essential for leveraging tourism and agro-food opportunities. Despite these barriers, women entrepreneurs in Greece demonstrate resilience, contributing to local economies and community development (; ).

In urban settings, Greek women entrepreneurs often engage in the technology and service industries, leveraging higher educational levels and urban infrastructure to launch startups and innovative ventures (). Networking is pivotal, with women leveraging formal and informal networks for support and growth opportunities (; ). Despite progress, societal expectations and traditional gender roles persist as barriers, necessitating policy interventions to enhance women’s entrepreneurial activities ().

Financial access is another significant hurdle, with gender biases affecting women’s ability to secure funding from traditional banking systems and venture capitalists (; ). Programs supporting women’s entrepreneurship, especially in STEM fields, are crucial for increasing women’s participation in higher-growth sectors (). Moreover, the role of education and lifelong learning in equipping women with the necessary entrepreneurial skills is emphasized in Greek policy circles, highlighting the need for targeted educational programs to foster entrepreneurial mindsets among women (; ).

2.2. The Stewart’s Role Demands-Constraints Choice Model

() introduced the demand constraint choice (DCC) model to offer a comprehensive framework for analyzing jobs in three significant ways. The model examines the behaviors of individuals in managerial positions as they perform their duties, with their choices categorized as either discretional or prescribed, depending on their perception of the demands and constraints of their roles. The minimum core of required tasks, activities, duties, and responsibilities that managers must perform is called the demand. At the same time, constraints are internal and external factors that limit what the role holder can do.

Applying ’s () DCC framework to entrepreneurship, particularly for analyzing the intricacies of women’s entrepreneurial leadership, offers a comprehensive approach to understanding the complex interplay between individual agency and structural factors in the entrepreneurial context. Conceptualized initially to assess managerial roles, the DCC framework’s adaptability lies in its foundational premise that external demands, internal constraints, and the strategic choices available to the role-holder shape professional roles. These elements are critically pronounced in entrepreneurship, as entrepreneurs must navigate a volatile market landscape and limited resources and make strategic decisions that directly influence business outcomes and sustainability. By repurposing the DCC framework to study entrepreneurial leadership, this study underscores the unique decision-making processes of entrepreneurs who, unlike traditional managers, often operate within less structured and rapidly changing environments. This adaptation allows for a deeper understanding of how gender influences these dynamics, thereby enriching the discourse on gendered entrepreneurship and providing nuanced insights into the barriers and opportunities faced by women entrepreneurs. The framework’s flexibility to accommodate these entrepreneurial specificities thus enhances its applicability and provides a robust analytical tool for exploring the multifaceted nature of entrepreneurial leadership.

According to the DCC model, the interplay between role demands and constraints offers opportunities for choices, which are behaviors that the role holder can adopt. Role behavior reflects an individual’s response to perceived messages and understanding of their job requirements. Role expectations create demands and constraints for the role-holder, and their behavior offers insight into the degree of compliance with these expectations. Stewart argued that leadership effectiveness is determined by the applicability of the role holder’s choices in a given situation. The three options described by Stewart included highlighting certain job factors, delegating tasks, and managing job boundaries.

The DCC model encompasses the various demands and constraints experienced by leaders at different levels, including the micro, meso, and macro levels (; , ). Recent research on women entrepreneurs in Kazakhstan (; ) offers several relevant and influential insights for the current study on Greek women entrepreneurs. The study conducted in Kazakhstan examines the interplay of gender, leadership, and entrepreneurship within a specific cultural and economic context, highlighting how macro, meso, and micro factors shape women’s entrepreneurial experiences. This conceptual framework, especially the application of ’s () role demands-constraints-choices (DCC) model, provides a structured way of understanding how these factors interact in different cultural settings.

For the Greek context, this approach can enrich the understanding of how societal norms, economic conditions, and individual traits influence Greek women entrepreneurs. Notably, the emphasis on the relational and social construction aspects of leadership seen in the Kazakhstan study can guide a nuanced exploration of how Greek women negotiate leadership and entrepreneurship within their societal constraints and opportunities. Thus, adopting a similar model could help identify unique challenges and drivers for women entrepreneurs in Greece, leading to more tailored policy recommendations and interventions.

Furthermore, the model emphasizes the importance of contextual awareness for leadership effectiveness. Greek women entrepreneurs encounter multifaceted challenges related to demand, constraints, and choices (DCC), significantly impacting their entrepreneurial endeavors (). These challenges are shaped by sociocultural, economic, and institutional factors that are deeply rooted in Greece’s societal structures. The intersection of traditional gender roles and the business environment often places Greek women entrepreneurs in a difficult position as they navigate entrepreneurial and domestic responsibilities.

The demand placed on women entrepreneurs often manifests as a heightened expectation of balancing their professional duties with caregiving and household responsibilities. This balancing act is particularly burdensome, as women must frequently mobilize familial resources to manage these dual roles (). In Greece, this demand became even more pronounced during the persistent financial crisis and austerity measures, which exacerbated socio-economic challenges (; ). The increased stress and time constraints from juggling these responsibilities can limit women’s ability to focus entirely on their businesses.

In addition to these demands, women entrepreneurs in Greece face various constraints that hinder their progress. Access to financial resources, technology, and networks remains limited, making it difficult for women to grow businesses (). Furthermore, gender biases and discrimination, particularly in securing credit and venture capital, further intensify these challenges (; ). These constraints create significant barriers to entry and growth for women in the entrepreneurial space.

Furthermore, societal norms and expectations are critical in shaping the choices available to Greek women entrepreneurs. Gender stereotypes often restrict women’s ability to pursue specific industries or scale their businesses, as societal perceptions of gender-appropriate roles and industries influence entrepreneurial decision-making (). These societal expectations can deter women from pursuing opportunities that may be perceived as unconventional by their gender (; ), thus limiting the scope of their entrepreneurial endeavors. Greek women entrepreneurs face complex challenges stemming from the demand to balance multiple roles, constraints of limited access to resources, and societal limitations imposed on their choices. Addressing these issues requires a comprehensive approach that considers the intersection of gender, culture, and economics in Greece’s entrepreneurial landscape.

2.3. Women-Led Entrepreneurism in Greece

The scene of women-led entrepreneurship in Greece is defined by an intricate mix of socio-economic factors, cultural impacts, and changing policy settings. Although Greek women entrepreneurs continue to encounter obstacles, such as restricted financial access, gender stereotypes, and the need to juggle family responsibilities alongside business obligations, they are increasingly crucial in driving economic innovation and societal transformation. Women’s unique perspectives and skills have a transformative impact in various sectors, such as the technology, services, and agro-food industries, driving business growth and community development. This change represents a bright future for entrepreneurship in Greece.

However, women entrepreneurs in Greece face difficulties in their journeys to success. Sex disparities are continuously maintained by systemic barriers, emphasizing the critical necessity for specific policy interventions and supportive measures. These actions are essential for improving the entrepreneurial environment in Greece, making it more welcoming and supportive for women entrepreneurs. An examination of the motivations, obstacles, and impacts of women entrepreneurs in Greece, intending to enhance comprehension of their involvement and influence across the wider European entrepreneurial environment, is needed.

Challenges Faced by Greek Women Entrepreneurs

Women-led businesses have been found to perform better than businesses led by men (). However, two issues are important here: first, what are the challenges faced by women entrepreneurs, and second, what are the challenges that women who do not become entrepreneurs face? When women leading businesses in Greece are asked about the most significant challenges they face, balancing business and family demands appears to be the one challenge that stands out (). The second challenge arises from gender biases, and the third challenge relates to unequal pay between men and women. Women entrepreneurs fear they will fail significantly more than men. While this is true for the OECD average, the percentage of women is as high in Greece () as it is for men. Women also report more difficulty finding funding, leading to fewer business ventures. The reasons behind the difficulty in finding funding are the more limited network of contacts women have, the fact that women entrepreneurs are, in general, younger and more risk averse (), the lack of information by women or their misinformation regarding funding opportunities and lack of time. The current startup funding system puts women entrepreneurs at a clear disadvantage, as shown in Table 2, depicting a gender gap comparison of women entrepreneurs across Europe, North America, and Israel. Women are found to avoid venture capitalists for funding and to especially avoid banks as they consider the latter immoral and think they would not be positive towards a demand for funds (). Women appear more willing to ask for funds from smaller funding organizations with a social orientation, EU funding, or participation in business competitions.

Table 2.

Gender gap comparison of women entrepreneurs across Europe, North America, and Israel. (SOURCE: Adapted by the authors from ’s () report data.

A potential source of information to address the second issue mentioned above, the challenges of women who did not become entrepreneurs, is a survey by ELSTAT (). Data from this survey suggest that only 8.0% of women, compared to 11.2% of men, report they prefer to work as self-employed rather than dependent employees. Around 47% of both women and men report that the main reason for not working as self-employed but as dependent employees is financial insecurity. Around 28.4% of women and 31.0% of men report a lack of funding as the main reason for not pursuing self-employment. Finally, 8.4% of women and 7.5% of men report that being self-employed would entail too much stress, responsibilities, or risk. Of those working as self-employed, 36.2% of women and 26.9% of men state they would instead work as dependent employees. There is no difference in the main reason put forward by men and women as the explanation for why they decided to become self-employed. Around a quarter of respondents reply that they are continuing the family business, 19% of women and 21% of men report that this is the typical pattern in the occupation they are following, 15% of women and 12% of men state they could not find a job as employees, and finally, 15% of women and 17% of men report that an attractive opportunity to work as self-employed arose.

A potential source of information to address the second issue mentioned above, the challenges faced by women who did not become entrepreneurs, is a survey by ELSTAT (). Data from this survey suggest that only 8.0% of women, compared with 11.2% of men, report that they prefer to work as self-employed rather than dependent employees. Approximately 47% of both women and men report that the main reason for not working as self-employed but as dependent employees is financial insecurity. Approximately 28.4% of women and 31.0% of men reported a lack of funding as the main reason for not pursuing self-employment. Finally, 8.4% of women and 7.5% of men reported that being self-employed would entail too much stress, responsibility, or risk. Of those working as self-employed, 36.2% of women and 26.9% of men stated that they would work as dependent employees. There was no difference in the main reason put forward by men and women as an explanation for why they decided to become self-employed. Around a quarter of respondents replied that they are continuing the family business; 19% of women and 21% of men report that this is the typical pattern in the occupation they are following, 15% of women and 12% of men state that they could not find a job as employees, and 15% of women and 17% of men reported that an attractive opportunity to work as self-employed arose.

Entrepreneurship is a critical driver of global economic growth and innovation. Table 2 () shows gender disparities in this sector, which can be observed across Europe, North America, and Israel. Regarding early-stage entrepreneurship, individuals in their nascent stages of establishing a business have a pervasive gender gap, where men’s participation typically surpasses that of women. For instance, the average participation rate for men in European countries is 10.0%, compared with 6.9% for women, resulting in a gender ratio of 1.4:1. Greece exhibits a smaller gender gap in early-stage entrepreneurship, with a gender ratio of 1.4:1, which aligns with the European average, but is noteworthy for its relatively high women participation rate compared to countries like Latvia and Croatia, where the disparities are much more significant.

The data are similar for owner-managers of established businesses that have been operating for a significant period and have a stable customer base, showing a pattern of gender disparity. Nevertheless, Greece showed a different trend in this category. It presents a high rate of women participation in established businesses at 12.4%, contrasting its rate for early-stage entrepreneurs, suggesting that while fewer women may start businesses in Greece, those who are more likely to sustain and manage them successfully compared to the average trend in other European countries. For example, Germany shows a more significant disparity in established businesses than in early startups, with very high gender ratios. Expanding the analysis to include international comparators, such as Canada, Israel, and the United States, it becomes clear that these countries also exhibit higher rates of men as early-stage entrepreneurs, with gender ratios similar to or slightly lower than the European average. Nevertheless, Greece’s position is relatively strong when comparing the rate of women’s participation in established businesses, suggesting a potentially more supportive environment for them, as entrepreneurs, to scale up their enterprises.

The pattern observed in Greece, as evidenced by the ’s () data in Table 2, indicates that while initial gender barriers exist in entrepreneurship, the environment becomes more conducive for women as businesses mature. This trend underscores the urgent need for targeted policy interventions to support women entrepreneurs in the early stages of business creation. Initiatives may include access to capital, specific mentorship programs, and networking opportunities tailored to address the unique challenges faced by women. Bankers and investors increasingly see the need to open access to women entrepreneurs’ financing as an ethical and social action and a catalyst for intelligent economics.

3. Research Methods and Approach

This study’s research methodology is grounded in a social constructionist perspective and interpretive epistemology () to explore the motivations driving Greek women to become entrepreneurs. Specifically, it investigates how they navigate the challenges posed by entrepreneurship in Greece, using Stewart’s DCC model. This methodological approach also seeks to understand entrepreneurial leadership as a gendered construct, positing that the perceptions and experiences of women entrepreneurial leaders are socially constructed through contextualized choices and constraints (). A purposive snowball sampling technique was employed utilizing LinkedIn to identify women entrepreneurs in Greece who referred to other women entrepreneurs. A total of 36 women entrepreneurs managing startups, microenterprises, and small enterprises were selected to obtain comprehensive insights into the perceptions and experiences of women leaders in Greece’s entrepreneurial landscape (Table 3). The selection criteria were driven by the central research question: What motivates women’s entrepreneurship in Greece, and how do they cope with their leadership challenges? This question is crucial for understanding the unique experiences of Greek women entrepreneurs and their role in the country’s entrepreneurial landscape.

Table 3.

Profile of Greek women entrepreneurs interviewed.

3.1. Sample Selection

Two researchers, one native Greek fluent in the language and familiar with the local culture, interviewed women entrepreneurs. The criteria for selection included ownership of an entrepreneurial venture and ensuring differentiation from other business activities. Participants must actively engage in leadership roles and self-identify as entrepreneurs, whether leading startups, operating as sole proprietors, or as part of leadership teams focused on business improvement and innovation. This study aimed to understand women’s abilities to develop and execute ideas within their leadership contexts. Additionally, participants were required to have at least three years of experience in management positions.

The inclusion criterion requiring a minimum of three years of entrepreneurial experience for this study’s participants is deliberate and scientifically grounded. This threshold aligns with the extant literature suggesting that entrepreneurs typically begin to encounter and navigate a full cycle of business operations—including financial planning, market fluctuations, and operational challenges—after the initial years of establishment. For instance, research indicates that businesses often face the ‘liability of newness’ where survival rates dramatically improve after surpassing the three-year mark (). This period allows entrepreneurs to move beyond initial start-up phases and experience substantive strategic, operational, and managerial challenges. Focusing on women entrepreneurs who have surpassed this critical early phase provides richer insights into sustained entrepreneurial activities, resilience, and strategic decision-making, thus offering a more robust understanding of the enduring factors influencing women’s entrepreneurship in Greece. This approach ensures that our findings reflect the experiences of entrepreneurs who have demonstrated some level of stability and continuity, which is essential for informing effective policy interventions and support mechanisms tailored to the actual long-term needs of this demographic. Only those actively leading in entrepreneurial environments were eligible for the semi-structured interviews.

3.2. Semi-Structured Interviews and Data Gathering

Written informed consent and consent signatures were obtained from all participants before the semi-structured interviews began. The consent form, available in a double-column format in English and Greek, clearly outlined that the interviews were noninvasive and posed no risk to the participants. It also stated that participants could withdraw from the interview at any time without any consequences. The confidentiality and anonymity of each participant were rigorously maintained to ensure that personal identifiers were removed entirely from the transcripts and analyses. This study did not require approval from an institutional review board (IRB), as the interview questions strictly pertained to business practices and decision-making processes, not personal or sensitive topics.

Semi-structured in-depth interviews (see Appendix A for questions used) were chosen as the primary data collection method because of their capacity to elicit detailed and rich narratives (; ). These narratives, embedded in the tradition of social construction, are suitable for comprehending the complexities of high-level positions (). Conducted in the spring of 2024, each interview lasted for approximately 60 to 90 min. The interview protocol was based on a literature review led by researchers with prior experience with similar studies. Stewart’s DCC model was used as a framework and was explained to the participants during the interviews. Instead of direct questions about job demands and responsibilities, the participants reflected on the nature of their responsibilities and accountability levels. Similarly, job constraints regarding obstacles, challenges, and daily work are discussed. Participants also considered their activity choices in light of demands and constraints, discussing why they chose certain activities and how they implemented them.

The bilingual researcher, well-versed in cultural nuances, played a crucial role in facilitating effective probing, clarification, and feedback during the interviews. Participants willing to be interviewed were asked qualitative questions to deepen their understanding of the identified themes and trends. Most interviews were conducted, recorded, and transcribed via Zoom, whereas others were conducted in person. Post-transcription, the data were coded and analyzed using Microsoft Excel and NVivo, highlighting and grouping frequently recurring responses. Data preparation included question verification, editing, coding, transcription, cleaning, and data adjustment to select the analysis strategy. The bilingual researcher translated and re-typed the interview notes into English when necessary, as many interviewees had a great domain of the English language. This process ensured that the original meaning of the interviewees’ comments was preserved, which was a necessary step during the coding and categorization process.

4. Data Analysis and Findings

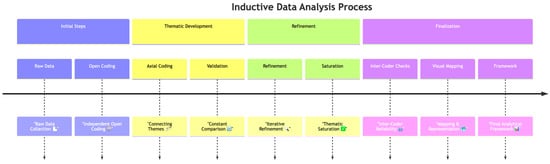

This study adopts an inductive approach to data analysis through the following general steps: gathering data, tabulating it, cleaning and formatting it, coding, grouping, visualizing it, correlating when appropriate, explaining, and drawing conclusions (). In the interest of more detailed methodological transparency in this inductive approach, several rigorous procedures were implemented to ensure the validity and reliability of the coding and classification processes. Firstly, a two-step coding process was employed. In the initial phase, open coding was conducted by multiple coders independently to categorize raw data into discrete themes based on their manifest content. This was followed by axial coding, where connections between these themes were identified and categorized into broader categories, facilitating the development of a comprehensive analytical framework. A constant comparison method was used to validate the coding scheme, and codes were frequently revisited and refined as new data were analyzed. This iterative process continued until thematic saturation was achieved, ensuring a robust data classification. In addition, inter-coder reliability checks were conducted, involving multiple researchers in the coding process to compare and resolve discrepancies in the thematic interpretations, thereby enhancing the validity of the coding process. Moreover, visual mapping techniques were used to represent the analytical scheme, including a detailed coding process flowchart, from raw data through to thematic categorization and the final interpretive framework. This visual representation, included in Figure 1, aids in clarifying the analytical process. The colored sequential diagrams and small icons highlight the phases of this research’s inductive data analysis process. It provides a clear, traceable path from data collection to conclusion, thus improving transparency and facilitating reader comprehension.

Figure 1.

Inductive data analysis process adopted in this research. Source: generated by the authors through Diagramingai.com.

A vital aspect of this process is the use of Stewart’s DCC model, a widely recognized and reliable tool, to analyze semi-structured interview data and identify common themes. This investigation aimed to identify common patterns in the demands, constraints, and choices among the various work experiences of participants in leading and making decisions in their businesses. Codenames were provided to interviewees to maintain their anonymity. The data coding process consisted of three steps: first, organizing by themes and spotting recurring ones; second, analyzing and categorizing the themes through axial coding; and third, reviewing using Stewart’s DCC model to pinpoint lower-level codes. The main categories focused on role demand, constraint, and choice, structured within Stewart’s DCC model to categorize lower-level codes.

Examining the data shows how role demands, constraints, and choices impact the leadership positions of women entrepreneurs in Greece. These three dimensions illustrate the dynamic and interconnected relationships within the leadership framework of women entrepreneurs. Figure 2 shows a word cloud created from the semi-structured interviews and the main themes in the interviewees’ minds. The Figure visually indicates the importance of challenges, constraints, and debt for many interviewees.

Figure 2.

Main themes arising from the semi-structured interviews with Greek women entrepreneurs. Source: word cloud generated by the authors.

In this study of Greek women entrepreneurs, the thematic analysis highlighted several critical themes centered on the dual pressures of professional business and funding commitments and family responsibilities, including the challenges associated with parenting, childcare, gender issues, and family. Although derived from a small sample, the findings suggest that these themes cannot be generalized but indicate significant trends. Greek women entrepreneurs often navigate complex roles, balancing business development with gender identity, inclusion, and familial duties, driven by a need for jobs, business opportunities, funding, and entrepreneurship. Their entrepreneurial endeavors serve multiple purposes: securing income, self-actualization, reaching out to their dreams, and providing for their families, mainly supplementing household income. This multifaceted engagement reflects a collective orientation that surpasses mere personal success by integrating business pursuits, familial obligations, and self-actualization into a unified analytical framework. This synthesis often restricts the convergence of personal and professional interests, highlighting ongoing efforts to actively manage these domains.

Moreover, these women demonstrate a pronounced commitment to work-life balance, embodying leadership roles that carefully consider professional advancements and preserve family relationships. This approach emphasizes the delicate balance between maintaining entrepreneurial ambitions and ensuring family well-being, reflecting the broader sociocultural dynamics in Greece. Their ability to balance these roles benefits their families and positively impacts Greek society.

4.1. Stewart’s DCC Framework Analysis

Stewart’s DCC model was adopted as an analytical lens to address the embodiment of leadership by women entrepreneurs in Greece and the influence of role demands, constraints, and choices on their leadership experience. While Stewart’s DCC model was developed concerning the demands, constraints, and choices faced by job holders, this is adapted here to consider the same dimensions regarding entrepreneurial leaders as also conducted by (). In this instance, the demands are not set by the employer but by the market or society and are prerequisites for the activity to be viable and succeed.

4.1.1. Role Demands

The leadership literature has not focused much on leader efficacy, especially regarding the demands and challenges women leaders face in business. This is somewhat unexpected since effective leadership necessitates elevated levels of agency and confidence. The interviewees underscored the profound significance of practical leadership demands, affirming their pivotal role in shaping leadership effectiveness. These demands, which are diverse in nature and scope, are primarily influenced by the ability to overcome obstacles and achieve success, a finding consistent with previous studies (). Notably, making progress toward a specific objective emerged as one of the most crucial demands, which often relied on opinions, partnerships, and the support of their spouses or business partners:

- -

- When I got married, I was over 40 years old, and I tried for many years to get pregnant. I lost the baby, and later, I was not able to get pregnant. At the same time, my husband lost his job and had a heart attack, and there was a lot of pressure and stress for me. I had to manage the finances and be strong for my family and company. (Interviewee 29)

- -

- I graduated from law school with my husband, and the first couple of years in the industry, we realized it was not for us. We are very creative, and we decided to open our own business. We make flower arrangements for weddings, baptizing, and other occasions and favorites such as wedding and baptizing favors. We started the business with our savings. We didn’t even look for any government help. (Interviewee 26)

- -

- [When managing demands] I consult with my husband. He has a background in economics, and I try to save as much as I can to use the funds to expand my business. (Interviewee 2)

- -

- As co-founders, we each have our niche in the business and consult with each other. However, my full-time job is to work for a German company, and I live part-time there. I get many ideas from Germany since they are more advanced than Greece. (Interviewee 4)

- -

- I’ve been trying every year to set my goals and assess our firm in the last few years. I bring this to my partner’s attention during our meetings, and we are trying some common decisions. Half of the firm currently does Criminal law, and the other half does corporate law. (Interviewee 16)

Interviewees highlighted the relevance of effectively managing challenging situations in their leadership positions, a topic that resonates deeply with leadership, organizational behavior, and business management. According to (), leaders who grapple with high role demands often experience increased stress and burnout, which can impair their decision-making skills and hinder effective team communication. The burden of numerous requests can also lead to role overload, impeding a leader’s ability to think strategically and plan in the long term (). The ability of leaders to effectively address challenges equips them with providing reliable perspectives on emerging situations and proposing practical frameworks for individuals in organizations and business owners (; ). This relevance is underscored by existing research, particularly in environments that are undergoing financial, investment, and socio-economic changes, as observed in Greece.

- -

- My goals are not going to be easy for my personal life because most of my free time will be invested in the business. I am also obligated to be with my kid, so I have to balance two careers and family. (Interviewee 12)

- -

- Funding from the government [to meet our demands] is completely useless in our case. (Interviewee 5)

- -

- Balancing family and both jobs is hard, as my mental health is the last I take care of. (Interviewee 17)

- -

- [The major demand and challenge] It was COVID-19, and meeting people was difficult, and I was alone. We were introducing something new to Greek and Swiss society, and conveying our vision was a challenge. (Interviewee 5)

- -

- My biggest personal challenge [in coping with demands] would be putting myself last. My mental health and physical health will soon need to be taken care of. I work 15 h a day, and it’s taking a toll on me. (Interviewee 16)

Interviewees revealed a broad perception of role demands, encompassing financial and non-financial returns on their business investments. Interviewees exemplified this perspective by emphasizing the interconnection between non-financial returns, demands, and overall performance.

- -

- Cash flow has been the biggest challenge. I didn’t have any stable clients. (Interviewee 15)

- -

- If they want me to go to their office, I go; otherwise, I rent a space. There are many places in Athens that I can rent by demand. (Interviewee 13)

- -

- I had to take the leap and leave my steady income and full-time job. My only regret is that I didn’t do it earlier. There was too much pressure, and I did it just to have a steady income. (Interviewee 6)

The interviewees viewed their role demands positively through effective leadership, which involved incorporating leadership traits, processes, and intentional behaviors to improve growth opportunities for leaders, followers, and organizations in various settings. In line with previous research, positive leadership has been found to enhance the environment, procedures, or result in its area of influence (; ). Noticeably, the feeling of responsibility towards supporters, partners, and stakeholders was crucial in linking role expectations and the pursuit of self-fulfillment among the participants. Positive leadership, in its conditional nature, is based on the virtues of flourishing within an organization and society. The findings of this study argue that the interviewee’s leadership actions function as the engine for positive organizational change, bridging the gap between individual virtues and organizational virtuousness and creating a feedback loop among both. To develop a positive organization, they had to make positive assumptions among (and about) their coworkers, a critical factor that instills optimism and hope in the organizational development process. This positive outlook positively impacts their business partners, employees’ personal and professional development, and clients. It balances favorable formal and informal conditions at work between business success, altruism, and service to the community. To do so, it is a sine qua non factor that, as an example of positive leaders, fostered their personal development by exercising virtues and developing practical wisdom. In this way, they give their followers a vision of the end towards the common good and set their organization towards their goals and dreams, dealing with demanding situations as they come ():

- -

- Someone came to my clinic without money to pay for their childcare. I didn’t charge them and also gave them some free medication. I learned that we must have a big heart and be human first, and money will come. That person had told their boss, who happened to be someone in the government. When I was in a meeting, they took me aside and thanked me for giving services to people that can’t afford them. It meant a lot to me because the patient had appreciated more than I thought. (Interviewee 7)

- -

- I try to be the best in my business. I strive for perfection. We have a constant clientele and strive to have new products and services. I try to keep the same employees. I educate myself and my employees. (Interviewee 3)

In this study, entrepreneurs’ resilience is defined as the ability of participants to successfully handle and adjust to obstacles, failures, and difficulties faced in their ever-changing businesses. It involves handling, bouncing back from, and reacting positively to entrepreneurship challenges, unpredictability, and setbacks. Resilience includes mental and emotional strength, determination, and a flexible mindset that allows entrepreneurs to recover from challenges, gain insights from their experiences, and maintain their dedication to entrepreneurial challenges (). One interviewee mentioned how difficult it was to try to coach a member of her team, deal with resistance (and possibly a generational gap), and then let the team member go to protect the business goals, vision, and business culture, highlighting the role of resilience in the learning process of entrepreneurship ().

- -

- There was a challenging case with a colleague of mine who was young and talented; she became very aggressive and uncaring. That was a challenge, and I’m very protective over young lawyers. She changed her style of clothing. It was very difficult in court, and she was not dressed professionally, showing more skin than a normal businesswoman. I spoke with her, and she told me that I was too old-fashioned. The new generation wants to look stylish on top of being smart. Her style looked inappropriate, and the image of our firm was in question. I had to discuss it with her, but she didn’t hear anything. She didn’t want to hear, and she was giving me a hard time, and everyone and I had to fire her. I learned from that that our intentions could be the best, but the other person might not understand them. At times, we have to make choices that are hard but necessary. (Interviewee 19)

The findings on role demands in this study highlight two important themes that need further exploration in the context of women entrepreneurs in Greece. They emphasize the critical role of emotional intelligence in helping entrepreneurs succeed; building trust, interpersonal communication, and inspiration are crucial skills for navigating today’s complex business environments. It emphasizes moving away from leadership based only on skills to provide current value from past accomplishments.

Additionally, these findings highlight the importance of women entrepreneurs in utilizing their interpersonal skills in their leadership positions. In today’s complex business environment, emotional intelligence, trust building, effective communication, and inspiration are essential relational traits. In contrast to competency-based leadership, these relational qualities are geared toward offering fresh and more fitting methods for future results.

- -

- We are the only girls who work, and we have hired cousins because we trust them. Since we can’t afford security cameras and the stores are small, we are more comfortable with family employees that we trust. (Interviewee 23)

- -

- Society is very backward here. They ask how you will take this seriously when you are a mother, and you have a full-time job. They show a lack of trust in women. (Interviewee 30)

- -

- … the vendors were writing my last name as a guy’s name and using my husband’s last name. So, instead of [name omitted], they were writing [name omitted] and my husband’s last name. I was laughing because I thought they didn’t know or it was a typo, but I might as well have expected a man to have this line of business. (Interviewee 28)

- -

- I have surrounded myself with partners and suppliers who respect me. However, with new partners and suppliers, I feel they do not take me seriously and give me doubts. I felt that with the company after we signed the contract, he started saying things in an abstract way. “If I explain it to you, you won’t understand it anyway,” I asked him to explain it to me on the business level because I would not hire them if I knew how to do coding. He was talking to me in a diminishing way, like calling me Sofaki, which is a name you call someone who is 1–5 years old. I stopped working with him. I fired the company that made me feel small and created a toxic environment. I made sure the new company knew the reason I fired the other one so this issue would not happen again! ((Interviewee 9)

While it can be assumed that spouses’ have a positive attitude and somewhat favorable impact on their wives’ entrepreneurship success, these quotes reveal that some women may not be fully aware of men’s influence and control. In a society where masculinity dominates, male supremacy and unequal gender power dynamics are common, even when women believe they are valued and influenced by their partners’ backing. This societal context underscores the urgency of addressing these issues. Women reject the notion that they are in a hidden state of submissiveness towards their spouses and are seen as objects of male attraction (; ).

4.1.2. Role Constraints

Interviewers believed that grasping the intricacies of role constraints in Stewart’s DCC framework could be difficult. The entrepreneurs who were interviewed found it challenging to articulate the constraints of their businesses because of the complex and constantly evolving nature of the limitations. Role constraints encompass various factors, such as organizational structures, interpersonal dynamics, and societal expectations, which are intricate and interconnected. Women entrepreneurs, particularly in demanding settings such as Greece, find it challenging to grasp the full extent of these constraints and their effects on their responsibilities. Their families’ expectations, societal norms, lack of experience, evolving business landscapes, and the absence of robust government policies influenced their entrepreneurial efforts, which contributed to the complexities these entrepreneurs deal with in understanding business requirements, funding opportunities, and taxation while handling their responsibilities in their tasks.

- -

- The hours worked were overwhelming at times. I had no options as in the beginning; it was just me. I sucked it up and worked. (Interviewee 25)

- -

- The market is big, but the pond is small. At times, you have to pick and choose not just your wins but also your losses. (Interviewee 27)

- -

- Building a bigger clinic with more offices was challenging because I had to choose a location away from the city’s center. Not many places outside of the center have good buildings and are more residential. I had to rent a house and turn it into a clinic. I learned that everything is possible as long as you are creative. (Interviewee 12)

- -

- The government should be more supportive and have more lenient rules on loans or business loans; that way, young professionals like me can have a better start-up. (Interviewee 18)

- -

- [Regarding looking for government assistance]... No, initially, I did not. I had no idea where to look… (Interviewee 24)

- -

- The government can be helpful with funds. Technology is very critical now, kids like smartboard practices and interaction. If I could have funds, I would update that sooner and faster. Training and coaching for business ideas and how we can improve. (Interviewee 28)

Greek women entrepreneurs often feel that they need more support to create a shared understanding with different stakeholders in their enterprises. This shared experience of challenges, as identified by recent research (; ), is a unifying factor among entrepreneurs in Greece. Difficulties can arise from cultural, organizational, or interpersonal factors, impacting the overall success of communication and collaboration in an entrepreneurial setting. They consistently emphasized the crucial significance of effective teamwork, underlining the importance of team dynamics and collaboration to tackle these limitations.

- -

- My neighbors of the older generation look at me weirdly, but kids my age always support me and often come to help me without pay. They just want me to be successful, so I guess it’s an older-generation thing. (Interviewee 11)

- -

- I have good help from my managers, and they support my dreams. (Interviewee 9)

- -

- Society is not an issue when developing a business. As of now, I have not faced that as a challenge. No one cares in my line of business because most are women, and we all support each other. (Interviewee 1)

From the perspective of role constraints, these interviews highlighted how leadership can adjust to a constantly evolving entrepreneurship environment. The Greek business landscape is becoming increasingly intricate and unpredictable. The obstacles that Greek women entrepreneurs and their businesses must overcome include technological advancements, market dynamics, and regulatory alterations. Nevertheless, the crucial adaptive and flexible leadership shown is essential for maintaining business success and continuity, providing confidence in the resilience of the business environment amid rapid changes.

Interviewees recognized the limitations of leadership actions when their established frameworks became overly rigid. Resistance to change is a significant obstacle to implementing a new business model, typically seen in startups and small businesses. These results agree with ’s () point of view and support current scholars’ opinions (; ), emphasizing role constraints’ fluid and dynamic characteristics. These constraints can limit specific options but also allow for other possibilities. The results indicate that these women entrepreneurs, utilizing their strategic mindset and business expertise, are willing to take calculated risks when they need to explore other options. Moreover, they combine fresh possibilities with their current business skills when assessing how best to adapt to the current business environment and cope with risk.

- -

- Risk management and any future perspectives for either clients or services. (Interviewee 1)

- -

- I analyze their risk management and the urgency of their business. I see their portfolio size as well. (Interviewee 13)

- -

- There is a market for diversity, but the older generation will never change in our area. The younger generation is slowly making changes and participating. (Interviewee 14)

As argued, Greek women entrepreneurs often perceive their businesses as integral facets of their lives, serving as conduits for self-actualization. They strive to configure their enterprises to facilitate mutual reinforcement and synergy between business and family roles. Recent research supports these findings, underscoring the continued significance of businesses in the lives of women entrepreneurs (; ). Echoing the sentiments of the interviewees, the principal constraints encountered by these women entrepreneurs in Greece revolve around a lack of shared meanings, insufficient resources, and inflexible contextual frameworks. Recent studies have elaborated on these challenges, shedding light on women entrepreneurs’ evolving constraints in Greece, such as the impact of changing societal expectations and economic conditions. Despite the progress made thus far regarding women’s entrepreneurship, it is clear that more active measures should be taken, focusing on financing end education. In particular, education is crucial because it may help change bias against women. Implementing policies for women entrepreneurs will help enhance women’s entrepreneurship, decrease unemployment, promote gender equality, and remove bias against women entrepreneurs and their obstacles (; ).

4.1.3. Role Choices

The interview data analysis revealed the interviewees’ subtle decision-making processes, explicitly highlighting the distinct difficulties and strategic factors they encountered in Greece. These women skillfully navigate various role options and carefully create alternatives that may not always be easily noticeable to outside observers. The complexity of these choices comes from meticulous consideration of role demands, recognition of role constraints, and evaluation of their believed potential for originality and innovation to determine a feasible path ahead. Women entrepreneur leaders in Greece demonstrate their entrepreneurial leadership skills by choosing the best options in uncertain and challenging situations, a concept well-documented in the current literature (; ). The results clearly show that women in Greece who hold entrepreneurial leadership positions make choices and decisions based on demand and constraints, which aligns with previous research in the field (; ).

In this context, role choice typically involves advocating for specific options that underscore the deliberate and strategic decision-making inherent in women’s leadership in business. Furthermore, the interviewees exhibited adaptability by employing a variety of soft and hard skill behaviors, adjusting them to specific contextual and situational factors, and balancing family, business opportunities, and stakeholders’ interests. This adaptability aligns with the intricate nature of entrepreneurial leadership and is corroborated by existing research (; ). In doing so, they confront the challenges accompanying their positions and contribute to shaping the evolving narrative of women’s leadership in business, thereby highlighting the captivating complexity of their decision-making.

- -