1. Introduction

This paper has four authors, but is generally presented by the first author (MAB) as the auto-ethnographer, in the first person. The second and third authors (ML and IQ) conducted many of the interviews, in collaboration with MAB. The fourth author (CAB) is the scribe, the data analyst and the “under-labourer” in the Hobbesean model of critical realist research pioneered by Roy Bhaskar, [

1], providing an ethical and logical underpinning of the research from an Islamic perspective. This research uses a novel or pioneering combination of methodologies in the field of business, in that it links critical realism (describing the “reality” of a situation with an initially critical eye, in order to hypothesise layers of meaning, and the proposed “real” causal mechanisms) with the role of “personal ethnography’, in that the first author offers significant insights into the process of understanding directions for future change (‘morphogensis’) from his personal experience of the business institutions and their environments which he is describing.

Work–Life Balance (WLB) policies, which involve state- and employer-provided benefits for employees through various motivations (e.g., profit-making entrepreneurship; public relations image; desire to recruit and retain well-qualified women; government policy and regulation; trade union pressures; feminist lobbying; and conformity to cultural tradition, as in some Islamic societies) are recent and controversial developments, and worthy of integrative reviews [

2,

3]. Exploring these issues in a focus on the cultural influences on WLB policy, this paper offers the findings of qualitative research on the nature and delivery of WLB benefits in two semi-public telecommunications companies, using semi-structured, qualitative interviews with 20 managers and 42 employees in telecommunication organisations in Gaza, Palestine, using a critical realist methodology in a series of qualitative interviews using standardised methodologies [

4,

5].

Critical realism adopts the ontology that the social world is real, and not socially constructed: but the nature of that reality is a matter for value judgement, hypothesis and speculation, which is best explored by qualitative methods. Critical realism has been applied with success in various business settings [

6,

7], and has been applied in the fields of education and social services, from contrasted value perspectives (e.g., Muslim and Catholic) [

8,

9,

10]. In applying critical realism in the present case study research, we have used the “under-labouring” principles of Islamic feminism, based on the writings of key Islamic feminists [

11], and the American feminist Judith Butler [

12,

13]. Butler (like Abu-Lughod [

14]) rejects Western critiques of Muslim women’s “oppression”, defending the assertion of traditional Islamic values, rituals and dress in cultures East and West, as part of a newly-developing and powerful Islamic women’s movement. “Under-labouring” is a value-based, Lockean concept which critical realism uses as a guiding thread which informs the logic and epistemology of a critical realist research perspective.

Autoethnography: In addition, MAB has used the perspective of

autoethnography [

15] to provide a qualitative, value-based account of a social structure enduring both high stress and an emerging Islamic feminism as women manage two distinct role sets, in family and work. The methodologies of autoethnography are now well-established [

16] and have been used successfully in Palestine [

17].

2. WLB and Gender

Women’s right to choose salaried work outside of their family home is central to understanding the nature and development of WLB, since an increasing number of economically active women in all cultures now typically continue to assume more family responsibilities than their male partners [

18,

19,

20]. The nature and quality of WLB policies are a central issue in feminist arguments on adequate policies for “working women’, which can reflect a variety of structural, political and value factors in different cultures [

21].

Chandra concluded in 2012 [

22] that for many in cultures both East and West, the purpose of WLB was to engender “a better life and for improving the well-being of the family”; but identifies the pressures of balancing work and family life in ways which can differ markedly between Eastern (e.g., MENA) and Western cultures [

22,

23,

24]. Lewis et al. [

25] and Kalemci and Tuzun [

26] both identify gender stereotyping and discrimination in Western organisations as being less overt than in non-Western countries, which are frequently more influenced by “traditional” cultural values-compared with the “secular” West [

27,

28].

Traditionally in Arabic countries, it is women who have been responsible for organising care for children (and for husbands and elderly parents), receiving little support from men in such roles [

29,

30]. This pattern of life is well understood in Arab organisations, who, traditionally at least, “tread carefully” in initiating policy changes (such as WLB benefits) which primarily benefit women [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. However, new concepts of “Arab masculinity” are emerging as women’s educational achievements increase, and male Arab leaders have carefully, slowly, but inevitably, recognised the employment equity of women. This seems to have evolved as a slow but enduring cultural change in the national self-concept of Arab nations [

8].

In some contrast, the concept of WLB in Western studies has usually involved individual satisfaction in multiple life roles, and the abilities of individuals to balance and manage simultaneously two or more aspects of life, including work, family and personal roles. For this purpose, various WLB policies have been developed in Western countries, such as part-time working, term-time working, childcare benefits and maternity leave [

34]. The various WLB policies offered by Western organisations may be classified under three main headings: Flexible WLB Practices; Leave Arrangement Practices; and Childcare Practices [

36,

37] (

Table 1).

Among the research questions addressed is the extent to which Western findings on WLB provision are relevant for an Arabic country, and the degree to which cultural context is important in the development of WLB policies in, for example, large telecommunication organisations, which often have significant international investment or interest, and management guidance. A key question is the degree of responsiveness of employers in Arabic cultures to the implementation of various WLB policies and practices, in the light of both local economic factors and the general norms which guide economic and business practices in particular Islamic cultures [

38].

Theoretical model The model emerging from this review is that there are several interacting factors influencing the type, quality and changing nature of WLB benefits in the developing economies of Islamic countries. Firstly, market forces only partially influence the kind and quality of WLB benefits in Arabic organisations, in contrast with those in the West. In Western (non-Muslim) cultures, the company’s concern with supporting women employees may also to some degree reflect union pressures (which are also quite active and independent of government and political parties in Palestine [

39,

40]) and politically-driven government regulations. In Islamic cultures, including Palestine, a company’s provision of WLB benefits will likely reflect generally accepted religious principles (e.g., the values of Islam), which influences the employer’s theologically-grounded benevolence, and the desire of the employer to present themselves as an “ethical” company, which treats both employees and customers well [

41]. It appears, too, from previous research that the introduction of human resource management policies by Western investors in Arab countries may transcend the commercial decisions of particular organisations, and may adapt to the culture, politics and religion of Arabic culture [

42,

43,

44]. The present study explores and develops existing knowledge and theories on the possible relationships between macro-level conditions and developments in HRM policies within organisations, Work Life Balance (WLB) policies, in an Arabic context.

3. The Context of the Current Study: Gaza, the West Bank and Palestine

Palestine is an Arab nation, whose population is more than 90 percent Muslim. Much of Palestine’s daily life has been controlled, directly or indirectly, by Israel, which has dominated Palestine since the war of 1967. Following an uprising against Israeli rule in 1987, large parts of Gaza’s infrastructure, trade and industry were disrupted or destroyed, and there have been severe economic problems, made worse by Israel’s intermittent warfare against Gaza between 2008 and 2022.

The two parts of Palestine, the Gaza Strip and West Bank, are geographically divided and under continued sanction, banned from free trade with each other and with Israel, and exports and imports to and from other countries are also often blocked [

45]. From 2011, more than 250,000 Palestinians were barred from working in the Israeli labour market, and the unemployment rate reached 26% in the West Bank and 33% or more in the Gaza Strip in 2011 [

4]. The male unemployment rate in Gaza had almost certainly increased to well over 50% by 2021, although accurate figures are hard to obtain [

46]. However, this UN Report estimates that the formal poverty level in Gaza increased from 44% in 2007 to 63% in 2017, largely due to lack of employment and inward investment. Data for Gaza and the West Bank suggested that about 17% of women were employed outside of their homes in 2021, plus an unknown but important number of women entrepreneurs [

45,

46]. Almost certainly, the female unemployment rate in Gaza is higher than in the West Bank of Palestine [

47].

Gaza (population 2.1 million+, living in 365 square Km of “the Gaza strip”) has one of the world’s highest population densities, so that the almost-annual warfare imposed on Gaza each year as part of the interminable blockade results in heavy casualties on civilian populations who have nowhere to escape [

48,

49,

50,

51]: around 3150 individuals (including 711 minors, and 345 women) in Gaza were killed by Israeli attacks between 2009 to 2022. In the same period, Gaza’s attempted defence resulted in 47 Israeli deaths (no women or minors were killed) [

52]. Between 2007–2018, Israeli action resulted in the destruction of Gazan infrastructure (buildings, hospitals, schools, etc., damaged or destroyed), plus a loss of economic development through blockaded of imports and exports, and deterred foreign investment amounting to an estimated US

$16.7 billion economic loss, with unknown losses to due to frustrated economic development [

47].

5. The Character of Business Enterprise and HRM Practice in Gaza, and in Other Muslim Countries

Palestine, like many Arab countries, is characterised by a “polychronic” culture [

60]. Individuals generally live in a relaxed manner, in which formal bonds of role and status are fluid rather than rigid (but subject to Islamic norms of interpersonal conduct, and the ethics of “modesty” guiding self-presentation and relationships between genders). Even within the workplace, roles, customs and norms from the wider society also often prevail. Individuals in Palestine (as in other Arab countries) feel less pressure to achieve high efficiency at work, which consequently makes the integration between personal and working lives both fluid and challenging for Western models, in which WLB practices are often premised on a rigid separation of work and family life [

61].

Intertwined with this Arabic cultural pattern are the ethics of business, which prevail in most Muslim-majority cultures [

62]. The religion of Islam informs a comprehensive system of values and ethical behaviours, and governs all aspects of life including the relations between individuals, and within society as a whole [

63,

64]. Being a Muslim involves accepting the Five Pillars of faith: acknowledging the power, wisdom and greatness of Allah; accepting the final message given by Allah to the Final Prophet, Muhammad; reciting the five daily prayers;

zakat—giving a prescribed portion of wealth and assets to charity, in order to create a comprehensive welfare system; fasting for a month during Ramadan; and if health and means allow, making pilgrimage to Makkah [

65].

The ethics of business enterprise in Islam are, ideally, based on Qu’ranically derived Shari’a law principles: “Shari’a is neither socialist nor capitalist: it takes a middle position between the two, and emphasises the common good (maslahah).”—Esposito and Delong-Bas, [

39] (p. 250). In such economic enterprises, Islamic “moderation and modesty” should ensure that “success” is balanced between several goals: doing good to the community (the zakat principle of giving); using resources wisely; not accepting interest on the giving or receiving of loans; not producing or marketing products which are harmful to health or the environment; and ensuring that profits made are distributed equitably with employees, and with the wider community—not to some remote group of international investors [

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71]. Given such an Islamic grounding of business enterprise, Work–Life Balance and HRM policies in Arabic and Muslim cultures are likely to have a special character, which international business has to appreciate for purposes of successful joint business enterprises.

In economically developing MENA countries, and this is likely also the case in Gaza, concern about income and overt power in organisations is a vital focus for men. However, at present, Palestine is enduring a highly stressed economic situation, and the job market for both genders is limited [

72]. Given this, along with some other cultural factors of men traditionally “rejecting” child care roles (and therefore neglecting associated WLB benefits), accessing Western-style WLB in the two Gazan organisations studied would hypothetically, for men, have low salience. Men would likely be looking for policy implementation which would increase income levels and enhance general welfare systems and which would effectively subsidize income and provide family support, such as overtime working systems, assistance with family health insurance and quality educational programmes for children.

6. WLB, Trade and Professional Unions, and Palestinian Labour Law

Large organisations in Palestine operate under the guidance of the Palestinian Labour Law, reformed in 2005 and regularly updated [

73], which applies to both Gaza and the West Bank. Several labour law regulations advise on (but may not require) the adoption of WLB practices, including paid maternity and child care leave for women (usually 3 months), with mothers also having the right to take unpaid child care leave for an additional year. However, according to the main trade unions in Gaza, there is still a need for further development, especially with respect to the limited application of flexible WLB policies by smaller firms. There are several unions representing the health care, industry, telecommunications and banking sectors [

74]. As in many Western countries, WLB “regulations” are often advisory rather than compulsory, and only larger or more progressive organisations offer WLB benefits which come near to providing for the union-supported aspirations of women who seek permanent executive, managerial or professional positions [

75].

The Palestinian Authority has tried to establish regulations which ensure the provision of basic rights of the workforce, including the right to maternity leave and breast-feeding hours before and after work, in all sectors of the economy (it is customary in Arab cultures for children to be breast-fed for their first two years). Compliance with such basic practices might not be the same as in other Arabic countries, since, whatever the guiding principles concerning family welfare derived from Islam, implementation is usually at the discretion of the owners or managers of organisations. Governments do not usually monitor “non-compliance’, and the adoption of WLB benefits seems, by and large, to be both voluntary and culturally specific in Arab countries previously studied [

76,

77].

In Palestine, there is some evidence that trade unions play a relatively strong role in the adoption of WLB practices, particularly in the larger organisations. This is so because of the growth of specialised unions in sectors such as telecommunications and finance, although the actual influence of unions on workplace conditions and rewards in Palestine has not been systematically studied. These unions have an important political and social function, protecting workers despite the fact that the economy of Palestine remains weak, with a ten percent decline in national wealth over a decade. Most unions and professional associations in Palestine which have support from the workforce (employed and unemployed) concentrate on primary issues such as job creation, job retention by employers and financial rewards (wage and salary levels), rather than on the implementation of other work-related practices and benefits.

In many Western countries, increased competition for skilled workers has resulted in businesses adopting WLB practices in order to attract and retain workers, particularly those with high levels of skills in relatively short supply [

78,

79]. In the case of Palestine, the current study had expected to find only a moderate relationship between the need to retain skilled employees and the provision of WLB practices, except for workers with special technical skills in limited supply. Thus, companies in Europe (as well as in the telecommunication organisations in Palestine which we report on below) may be motivated to provide benefits in order to recruit employees in a relatively competitive environment for skilled labour. This practice may be influential in international organisations seeking employees with a high levels of English proficiency, IT skills, and telecommunication and engineering backgrounds—such individuals still remain in short supply in Palestine. This may place women with such qualifications into a position of relative power within the employee/employer relationship, if they possess skills required by such organisations to compete effectively on a national and global basis.

Despite the economic and security pressures on Gaza, we expected that research would show that the general influences of Arab society, culture and practices would produce a more relaxed and even generous approach to WLB, due to the fluidity and interchange of the roles of work and home activity. This factor, combined with the unique skills sets possessed by women, may modify power relationships, enabling women to exert pressure on employers to provide family-friendly conditions [

62]. This apparent progress of Palestinian women is described, for example, in the comparative MENA study of El Feki et al. [

80].

7. Research Methods

In order to gain both an in-depth and critical realist understanding of the perceptions of employers and employees on how the implementation, adoption and administration of WLB policy are applied, the longitudinal case study strategy is a fruitful way of approaching a novel research topic, in which an unfolding and changing reality becomes embedded in the researcher’s values and perceptions [

81], and may be combined with an auto-ethnographic study which is particularly appropriate in Arabic cultures such as Palestine [

82]. Combined with these qualitative approaches to understanding, purposive sampling of employers and employees was used in two case studies in the telecommunications sector over the period 2015 to 2021, interviewing senior and middle managers as well as a cross-section of employees. The researcher had a particular focus on female employees, who hypothetically were those most likely to need and to use WLB benefits in relation to family and child care. During this period, the researcher tried to obtain a deeper and sympathetic understanding of “the quiet revolution”, which has involved the emergence of a class of Muslim women who are successful professionals, managers and entrepreneurs, and are accepted and supported in these roles by husbands and by male colleagues [

20,

49].

The two largest telecommunications companies in Gaza, Palestine, were approached, and agreed to participate. These two companies are “semi-private” in that half of shares are owned by the government, with the remaining stock being held by private organisations and international investors. Both companies have a strong public profile and are known for their apparently progressive human resource policies regarding their relatively high proportion of female employees. Both companies have also received subsidies and telecommunication equipment from European entrepreneurs such as Ericsson, who continued to support the Gazan companies even when communication centres and signal towers were destroyed by intermittent warfare.

It is relevant to observe that Israel has complete control of any equipment (e.g., mobile phones and their technical supports imported into Gaza.) This has led a critical policy group to comment: “Communications infrastructure in Palestine has become a tool of repression: restrictions on Palestinian mobile companies mean that Israeli companies reap profits from Palestinian customers, while Israel benefits from the resulting surveillance capacity and propaganda tools.” [

83]. Communication networks in Gaza are entirely controlled by Israel, and only in 2021 was an Israeli-owned 3G signal allowed, meaning that international calls are still not possible. Israel has listening capacity for all mobile calls made in Gaza, which may be a useful security or control strategy.

The findings presented in this article result from the analysis of 62 interviews (with 20 managers and 42 employees), including 23 women (37 per cent) and 39 men (63 per cent), which broadly reflects the percentage of gender distribution in the Palestinian telecommunication sector, but is somewhat higher than that in the general Palestinian workforce [

84]. As of 2022, all ten senior managerial positions in PalTel were held by males. No special sampling frame was used, but as many managers as possible were approached, and groups of employees in Gaza were recruited on an opportunistic basis. None of those approached declined to be interviewed. All open-ended interviews were recorded in Arabic by male researchers, who were business studies researchers at a Gazan university, with one subsequently being a researcher at a European business school. The setting of the interviews (a private room on company premises) and the clear approval of senior management for the study implied the expectation that responses would favour the companies’ reputation and prestige. This implies an implicit “conservative bias” in responses—but many employers seemed to be both frank and critical in their comments on company policies and actions of their colleagues regarding WLB policies.

The private interviews were carried out across most of the directorates of the telecommunication companies, including senior management: VPs, and heads of HR, financial, procurement, marketing and IT departments. Employees, both junior and senior, came from a range of staff: administrative officers, salespeople, accountants, IT, HR people and others. A number of the employees interviewed had either supervisory or managerial responsibilities, but in our interviews, we sought their views from the perspective of being a collaborative member of the company, rather than as managers as such. Management clearly expected that the interviews would show the most positive features of their organisation, although in the interviews, we recorded both positive and negative views and experiences. All interviewees were guaranteed anonymity. The recorded and transcribed fieldwork interviews (in Arabic) were translated to English and further transcribed, coded and analysed according to the methodological guidelines of King [

85], and of Bryman and Bell [

86] for the thematic analysis of qualitative data by an independent researcher.

The interviews involved a semi-structured approach, ensuring that the issue of WLB policies was central, although participants were not constrained in terms of raising other employment issues they thought to be relevant and important [

4,

87]. The semi-structured interview covered the most important interview questions within the limited time available with senior management. In adopting such a non-directive approach we asked interviewees to define for themselves what constituted the reasons for adopting WLB policies within their organisation. Consistent with a critical realist model of research [

6], we did not make initial hypotheses on reasons for adopting WLB policies.

The

Critical Realist research approach records and analyses values identified in the research process, but does not necessarily accept existing theories concerning causality in social structures: rather, this approach seeks to identify and understand the sub-layers of meaning and motivation involved in the adoption of WLB policies, such as religious and cultural values. Thus, we allowed participants in their own way to explain the meanings and “sense” regarding assumed reasons behind the deployment of WLB policies. Our analysis results from the idiosyncratic explanations of our respondents and our own understanding of WLB policies which emerges from the participants’ perceptions of their working environment. At this stage of the research, we aimed to obtain a holistic picture of each organisation, and found that human relations within them were complex and multi-layered, with separate and sometimes conflicting epistemologies, which required a critical realist appraisal and understanding: “Critical realism… does not assume reality to be a single, observable, measurable, determinable layer whose actions and events are independent of the mind nor a single layer that is understandable through exploring experiences and perspectives. Critical realism assumes reality to have multiple layers containing structures and mechanisms that influence the observable and what can be experienced. It is the exploration of these structures and mechanisms that provides the basis for exploration of reality using critical realism.” (Daracott, p. 1) [

86].

Following the qualitative, critical realist approach [

6] we made no initial hypotheses on the nature and use of WLB policies, although, of course, the researcher’s implicit value premises (for example, in favour of Muslim women’s equality) were often manifest in intuitively identifyng the meaning and primacy of the structures identified. We allowed participants in their own way to explain the meaning and sense with which they regarded WLB policies and benefits. Our analysis and speculations result from the idiosyncratic explanations of our respondents and the researcher’s changing understanding of WLB policies which emerged from the participants’ perceptions of their working environment, as well as from our own changing consciousness of the struggles of women, based on his personal experience and the principal researcher’s evolving “autoethnographic” perspective [

50].

The critical realist (CR) research framework was also used as a guide to “codes for analysis”. Certain significant themes derived from the initial interviews were used both in later interviews and for coding the data within concepts such as: “Islamic beliefs of the individual” and “family situation’. After intensive reading and rereading of data transcripts, many more codes were applied to the transcription of the interviews, which segmented the data according to their similarities and sub-groupings [

85,

86,

87,

88].

8. Results and Discussion

Analysis of salient codes indicated that managers in both companies cited six main reasons on why their companies adopted WLB policies. These were: (1) Social and cultural factors; (2) Regulations of government; (3) Needs of women employees; (4) Competitors’ policies and the need to recruit skilled personnel; (5) International networking; and (6) The pressures of labour unions. The emergence of social and cultural factors and international networking are new findings, and are discussed below in more detail. These six factors and their impact on the adoption of WLB policies are listed in the following table, which highlights the sometimes-contrasted opinions of managers and employees (

Table 2).

“Strong” in the above table means that the majority of managers and employees agreed on the postulated relationship. “Weak” means, that a minority (or indeed, very few) agreed on the relationship. The symbol “-” is used when there were no participants mentioning the relationship. Regarding the impact of social factors, Palestine is

polychronic in nature [

60,

89], in that most individuals do not clearly separate external work and their social life and interactions. Both companies, for example, had adjusted their policies in order to accommodate these cultural factors: ”It is normal in Palestine for people, whether they are managers or employees, to have visitors or to speak to family and friends on the phone during working hours. It is accepted and common in most of organisations.” (e.g., Manager 10 and Employee 24).

The data suggest, too, that the adoption of social policies may, as in Western organisations, also derive from a “benchmark’, whereby organisations follow what has already been established in the marketplace [

90,

91]. Otherwise, as Manager 5 stated: “The organisation becomes outside of the accepted mode of acting”, which might not be acceptable for employees. The social and management practices of the companies studied (MobileCom and PalTel) are a potential challenge for international management, and while management does not prohibit the acts derived from these cultural norms, it establishes some regulations on how they should be applied: “You can manage and control the intrusion of private life into the workplace, but it is difficult to avoid because it is common in the entire society. People have little respect for working time and are used to integrating their personal life into their working life.” (e.g., Manager 16).

This quotation highlights

the cultural system of Palestine (probably similar across the Arab world), in which people frequently place their private life and the demands of family as equal to the demands of their work. This is the norm within this Arabic cultural context and almost certainly would not accord with expectations in a Western context. Moreover, even if religious practices conflict with the requirements of working time, such as ritual washing (

wudu) and praying two times a day for around 40 min in total in the working day, the organisation has little choice but to grant such entitlements [

64]. “We are a Muslim society…Prayer and Hajj for example, are compulsory policies for all Muslims and they are obliged to follow these policies in order to fulfil their religious duties. They are very common in most of the organisations and it would be a shame to prevent someone to have them.” (e.g., Employee 18, and Manager 12). Thus, any employee undertaking the Hajj pilgrimage will be salaried for the weeks this takes, in addition to annual leave.

Government regulations were identified as another reason for adopting certain WLB policies, and this was certainly the case for the leave policies: the adoption of most of the leave policies is related to the rules and the regulations of the Palestinian Labour Law (most participants). This is consistent with studies in Western countries [

92]. Labour laws certainly influence the structure of HR policies and strategies of the Palestinian companies studied: leave policies are derived from the regulations of the labour law. This can be seen in the employment contracts, HR policies and other documents where such policies are highlighted according to Palestinian labour law. (Managers 1 and 5). Working hours, length of holidays and contractual work were aligned with the guidelines of Palestinian labour law. However, with regard to flexible policies, in contrast to many Western nations, their existence in the telecommunication companies was not prescribed by government. Ministries in Palestine establish many regulations, auditing systems and inspectors of employment conditions [

43]. However, the progress of labour law enactment is slow, reflecting various economic and political circumstances, unlike Western countries such as Germany or Sweden, whose policies the government in Gaza seeks to copy, with appropriate cultural modifications [

93,

94]. However, in the development of parental leave, Palestinian labour law guidance did fit the unpaid leave format which the government recommended: “The organisation complies with government rules and regulations and the changes introduced in 2005 which give women a right to reserve their place at work for a year after giving birth.” (Employee 14/Manager 10).

This policy of granting unpaid parental leave for up to a year is, apparently, the result of social and cultural changes such as an increase in the female workforce, a decrease in the influence and use of extended family culture, and pressure from women’s non-profit organisations—many women graduates in Gaza are sought after by the NGOs which deliver education, health care and social support [

42,

93].

Contrasted viewpoints emerged regarding relationships between the adoption of WLB practices and pressures and advocacy by labour unions. According to most managers, the labour union has a strong membership, conducting a vigorous lobby together with other unions in Palestine [

95,

96,

97,

98]. The relevant unions also tend to work co-operatively with the tele-communications industry, generally seen as “model” employers. This meant, according to most managers, that union pressure on this particular sector of industry, was necessarily minimal: “The Labour Union only manages and runs social activities in the organisation. Obliging the organisation to provide additional benefits to the employees is not their focus… No, I don’t think benefits shave been introduced, such as “financial and flexible policies” because of the labour union… I think management has introduced them to assist women and to the benefit of the organisation.” (Managers 3 and 10).

The voice of the workers represented by labour unions was expressed strongly (according to most women) only with regard to social and family activities. This would be in line with several Western studies that also emphasised the limited voice of labour unions in organisations insofar as WLB initiatives were concerned [

95,

96]. As many managers observed in the two companies, because they offered policies which individuals would in any case demand, the role of the labour union within the organisation was limited: “What are the labour unions going to discuss? Every benefit that the employees can think of is available. Employees here are receiving a greater number of benefits than in any other workplace. What is the maximum benefit on the agenda of the labour unions? They are less than what the organisation itself offers.” (Manager 8).

Certainly, the initiatives of the management were responsible for the adoption of many WLB policies, in order to assist with organisational strategies and objectives. The labour union had a limited voice in this respect, and the employees’ views were often consistent with those of managers. The employees, however, believed in addition that the labour union played a vital role in raising interest in and the adoption of certain WLB policies: “The labour union played a role in improving the workplace environment, and this is mainly reflected in financial WLB policies and study leave, but we cannot say that MobileCom adopted leave or childcare policies because of the pressure of the union. (Employee 2). The Union had been active for about six years, and most employees felt that the Union has shown a significant pressure in improving financial policies, study leave, and other benefits. It is up to the company whether they consider us or not... but I agree it was fundamentally the decision of the management rather than our voice.” (Employee 13).

According to nearly half of employees, the role of the labour union was now quite strong: “We have now a union body in the organisation that has a strong relationship with other unions, and most employees are members and work under its umbrella…the union played a strong role in the negotiation process with management and if they don’t agree about some issues, they have the power to suspend work or call us to go on strike.” (Member of the labour union, Employee 18). The voice of the labour union appears, according to employee accounts, to have contributed to or indirectly supported the enhancement of WLB benefits within the organisation, in a co-operative endeavour in consultation with management. This finding is different from studies in Western countries [

99]. In Palestine, government and non-profit organisations have tolerated or even encouraged the role of labour unions and the extent of union pressure on the marketplace, since they offered a range of welfare services even when they cannot effectively use labour law to protect wages and employment security [

42]. The presence of women as members of the labour union committee in the two organisations studied also appears to have strengthened the negotiations of women to achieve better leave and childcare policies. Nevertheless, because of some cultural factors, including a paternalist management style (discussed later), the relative positions of managers and employees showed some tensions.

International collaboration and networking emerged in the research as a reason for adopting WLB practices. Networking did not emerge as a strategic alliance, and MobileCom and PalTel had no specific partnerships with any international organisation, although they were totally dependent on Israel to access the signal network for connecting calls. Participants in the study emphasised that an increased awareness and adoption of some leave WLB and childcare policies was associated with co-operation and networking with major European providers of telephone equipment: “Many of our management team visit these international organisations and vice versa, to learn about the latest developments in different fields…the leave policy that offers men holidays to look after their wives are derived from our experience with companies such as Eriksson…It is also from the current CEO who also has work experience at NASA.” (Manager 6 and Employee 18).

International experiences and collaboration have enabled the two companies to import knowledge (and visiting advisors) from Western countries. This appears to have had an impact upon employment strategies, and some WLB policies are associated with this influence. These contextual features, and the unique international style of a particular company, influenced the adoption of certain WLB policies: “The networking with international organisations requires a high level of standards and proficiency to enable us to interact and communicate with them. Without this capability level in respect to the management system the organisation would remain outside of this type of collaboration or any network.” (Manager 3)

This finding is in line with earlier studies [

60,

100,

101] on changes in organisational policy designed to fit in with cultural differences within the various regional offices of international organisations. To have a working model that plays a role as part of an international organisation, it seems necessary that the two Palestinian companies should offer such benefits: “Additionally, every year an international organisation such as H-GROUP, acts as a consultant in MobileCom.” (Employee 4). This group offered advice on how to develop working arrangements in, for example, departments such as HRM: “H-GROUP was improving the system of promotion, leave policies and childcare services.” (Employee 14 and Manager 4). Thus, both companies played a role in the development of both their own and internationally derived WLB policies: “It should be noted that the existence of paternity leave policies for men does also exist in some organisations in Palestine, especially the international ones like the UN, UNDP and the Arab Bank.” (Manager 3). This offers some evidence that international factors have had an impact on WLB policies. This policy is neither required by Palestinian law [

74], nor was it in high demand in a masculine-oriented Arabic culture, according to the interviews and fieldwork for the present study.

Various insights emerged from the findings concerning the relationship between competition in the market and the adoption of WLB policies. Most of the managers stated: “The adoption of any policy in our organisation relies on our strategy and employee demands rather than from any pressure deriving from competitors in the market. We are innovative. (e.g., Manager 5). Increasing financial policies, childcare and family holidays have been the organisation’s strategy for a long time, but we adopted them three years ago in order to compensate workers for their performance during the year.” (e.g., Manager 8).

The “generous” WLB policies at MobileCom (including child care support) arose ostensibly from the organisation’s own initiatives to improve the working conditions of their employees. External pressure, such as the introduction of WLB policies as a response to changes in the competition for labour, was usually downplayed by management. This finding is in line with a few studies conducted in Western countries [

99]. Several employees, however, did stress that the adoption of financial WLB policies was also due to the competition for high-quality workers, and the entrance of new companies in the market: “Why did the organisation adopt family holiday this year? We asked about it three years ago, and only now has it been adopted… and why were many managers asked to sign a contract with the organisation guaranteeing that they will not leave the organisation for at least five years; this is due to the entrance of new competitors in the marketplace.” (Employee 16).

There are new telecommunication companies emerging in Gaza, along with an increase in non-profit institutions which all offer a competitive salary and fewer working hours for well-qualified women graduates with proven experience. Given the increasing competition for skilled labour, and an increase in opportunities for the well-qualified to find employment through emigration, it is not surprising to see a growing focus on adopting WLB policies to retain good employees. This finding is in line with studies in both Western and developing countries [

100,

101]. Several employees also observed: “Current provisions such as, financial and flexible policies are in place because of the high concern about retention, and sometimes attraction of employees… If you are flexible, you will retain and keep people in workplace, especially the highly skilled males and females in the workforce.” (Employees 4 and 10).

Flexible and childcare policies appeared to be vital for the two companies, in order for them to compete with other institutions in attracting and retaining well-qualified female employees. Given cultural and religious pressures, women in Arab society are probably more attracted to public organisations and to any organisation that offers limited working hours to enable them to fulfil parallel family commitments, for reasons grounded in cultural patterns and religious values (which, in Arabic societies, are strongly intertwined). Thus, organisations may feel obliged for cultural and religious reasons to apply favourable WLB policies for their female workforce.

In the present study, there is a clear relationship between the presence of women in the workforce and the provision of various WLB policies in both companies: “It is the consideration of women, which is behind the adoption of many policies of WLB.” (Most of the participants). This response was consistent throughout, and was especially emphasised with regard to childcare provision, flexible hours and leave policies (e.g., following the birth of a child). This is in line, too, with several studies from Western countries [

102]. Thus, in Gaza, an increasing number of married women have exerted pressure on their employer to provide excellent WLB policies: “About six years ago the childcare policy was adopted by the organisation. Before that, we did not have these benefits. I am sure that this was because the number of women at MobileCom was low at that time. The policies are the result of an increase in the number of women employed, and especially married women who were choosing to leave permanently, have babies.” (Manager 1).

When Arab women marry, they used, in previous decades, to stay home, or work where they had limited working hours [

103]. However, now with pressures from implicit, “everyday Arab feminism” [

104,

105], organisations now feel pressured to increase WLB facilities in the workplace to fulfil the needs of female employees. Several women in the present study observed that the women workforces have the power to negotiate and discuss their needs with managements: “As women, we have put forward a proposal, with supporting documents, to indicate the level of difficulties encountered, in our meetings with management. They were respectful and appreciative with respect to our demands.” (e.g., Employee 17). This female workforce clearly had the power to try and negotiate and potentially obtain the policies they seek in order to satisfy personal and family requirements. This could be due to the shortage of highly skilled employees, and also to the existence of labour unions that support the female workforce.

9. General Conclusions

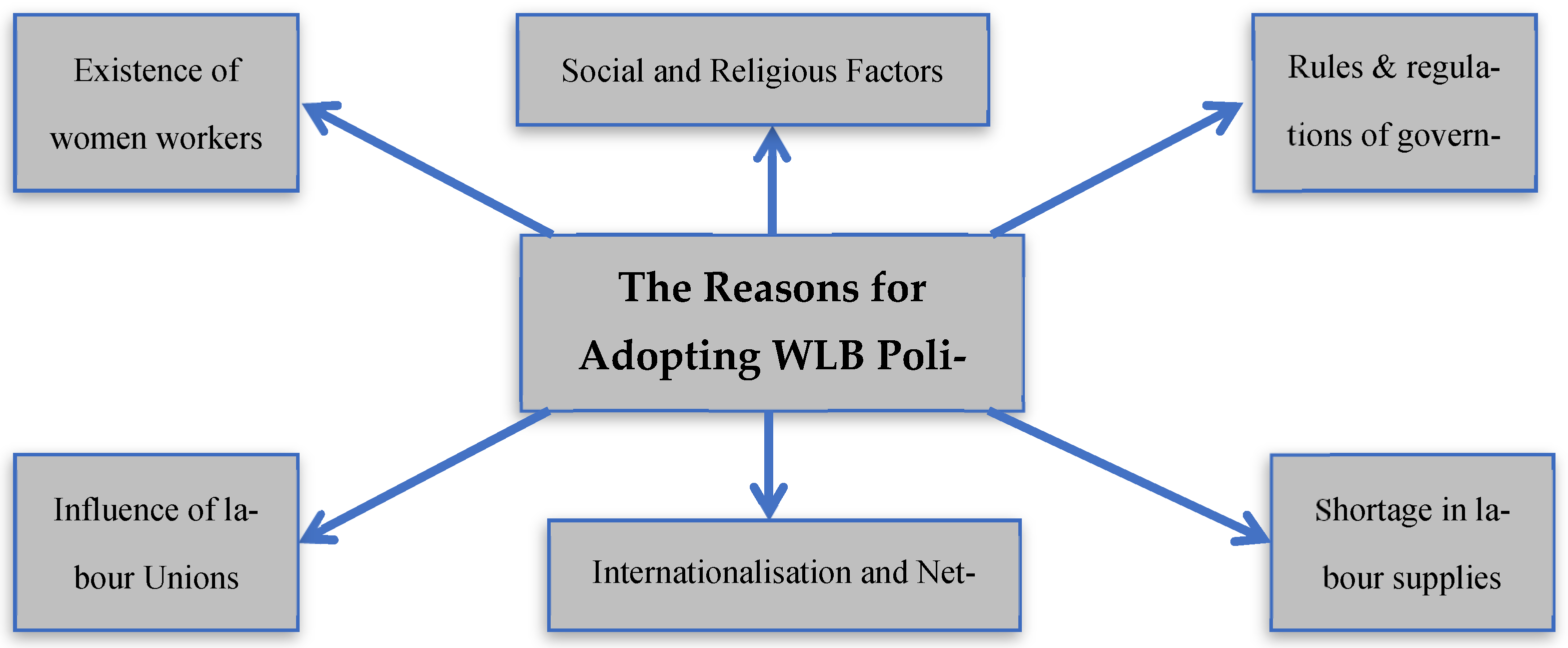

This study has examined some of the declared reasons behind the adoption of several WLB practices, compared with the many reasons behind such adoption in Western organisations—including regulations of government; the pressure of labour unions; the extent of women participating in the workforce; and cultural and religious factors. According to the evidence from this study, Islamic values and a cultural pattern of social relationships in Palestine, in broad terms, and the continued blockade of Gaza in particular, have played a major role in the emergence and adoption of a number of WLB policies in the organisations, which are particularly helpful to women (and also for men, including stress leave for employees who have been bereaved or wounded by intermittent warfare, and grants for relocation or rebuilding when warfare has destroyed homes). Additionally, networking with international organisations has also influenced the “importation” of certain WLB policies into the organisation. These factors, along with others which play a role in the adoption of WLB policies in telecommunication organisations in Palestine, are outlined in the following diagram (

Figure 1).

This diagram incorporates several key factors which may interact with one another in influencing WLB adoption, including international and networking factors which have quite a strong influence, according to the interview evidence. Overall, the organisations offered important WLB policies because of religious and cultural factors which were not intrinsically beneficial for organisations, such as receiving personal visitors and using phones for personal use for quite lengthy periods during office hours. Understanding the social and religious obligations which employers feel the need to accept will be valuable guides to multinational companies investing in, and setting up businesses in, Arabic countries.

The current findings also point to the importance of understanding and considering different levels of general social, cultural and religious systems of any society for understanding the reasons underlying the need to adopt particular HR policies within a nation. Misunderstanding some factors could lead to significant difficulties in multinational development. What is impressive from the accounts of managers and employees is the stoic determination of the two companies to “carry on” under conditions of blockade and warfare in providing significant WLB benefits, including those which were particularly helpful to women. Most impressive were the actions of the two employers in providing financial assistance and the rehabilitation of injured and bereaved employees resulting from Gaza’s intermittent warfare with Israel, and assistance for war-damaged house repairs. Similar kinds of findings emerged, too, in a parallel study of schools and teachers who assisted injured and bereaved parents and children following episodes of warfare [

50], and indicate the Islamic principle of

zakat (charity for all) being absorbed into organisational and WLB policies.

This research supports some previous Western studies on the importance of the percentage of female employees [

106] and the role of government [

92] in explaining the diffusion of WLB programmes. This is an interesting finding, given that both institutional and cultural factors are markedly different from those in Western settings. In fact, in Palestine, the female workforce impacted significantly on company practices, probably more so than in organisations in the Western context, notwithstanding the smaller percentage of women in the workforce. This is likely due to cultural factors concerning the female workforce, with societal norms which traditionally have pressured well-educated women not to give up homemaking and child care roles, even when they occupy work roles outside of the home. Without some flexibility in the WLB system, valuable women (who, in the telecom industry, have marketable skills and experience) might leave the workforce permanently.

This research has identified the most salient or manifest factors which influence organisational WLB adoption in two case studies in the telecommunications industry over a 5-year period in a developing country, and offers the potential for extending existing knowledge of the relationship between macro level conditions and developments in HRM policies within organisations: the development of WLB policies is not limited to a business case philosophy (based solely on profit motives) but also involves institutional pressures within specific cultural contexts, which are important for international investors to understand and co-operate with. The study interviews, and our parallel ethnographic understanding of change and stress in Gaza, provides detailed information about the context and the stance of various interlocutors concerning WLB practices. There is, in fact, no previous case study research on organisational WLB practices in Palestine, and few studies of any kind which have employed a detailed case study or ethnographic methodology in describing work organisation and practices in any Arabic society. This study, therefore, offers the basis for further research on the most salient factors determining organisational WLB adoption in developing countries in the Middle East.

Additionally, this study has identified some cultural factors which researchers may take into consideration when investigating aspects of business and marketing in Palestine, and in other Arab and developing countries. This research, for example, has identified the residual but continued importance of the paternalistic cultural style or “Fatherhood system”, and the influence and charisma of individual, nominally prestigious male figures in society and business enterprises, which has implications for research in other Arab contexts. Male Palestinian managers who construed their world in this style failed, however, to adequately present the power of labour unions and market competition as reasons for the adoption of WLB policies. Many managers presented different reasons behind such adoption when interviewed by the researchers (i.e., not the “real” reasons, from a critical realist understanding of the structure of business). This seems to be a common reconstruction of knowledge in Arab cultures, since such frankness (or the dawning of understanding) might undermine their presentation of personal power (and traditional male dignity) in the organisation, and in society.

Although this study offers deeper insights into the phenomena of WLB policies in the Palestinian telecommunication sector, the findings remain uncertain without further research (for which the present study may be a valuable starting point), on the generalisability of the findings beyond purely Arab contexts. Although this qualitative enquiry has provided satisfactory data to expand on some existing theories, the findings of the study should be read within a context that is “relatively” unique: further research could be carried out in different settings, which might contribute to the acquisition of a deeper understanding of WLB issues.

Overall, the present research and the available studies reviewed have indicated that there are issues of organisational culture, social, culture and religious issues in specific countries, which are stronger than the directions of government, or of the profit-driven demands of the market. Given this, research on WLB’s nature and delivery needs to be replicated on a country-by-country basis.

10. Critical Realism and Autoethnography: Morphogenesis and Value Change

According to Daracott [

86], critical realism involves identifying “multiple layers of reality” involving complex interactions by individuals and strata in a process in which social change is achieved through “morphogenesis” [

9,

10], the exchange of value-based ideas by actors whose roles and voices have varying degrees of power in the relevant interactions. Thus, (for example) the genesis of WLB policies involves value-based interactions by actors with differing degrees of power, differing goals, and differing perceptions and understanding of how change can be achieved. In the present research, the writer has focused on the changing roles of women and their achievement of new and more powerful roles (e.g., as employees in developing companies), in ways which serve their dual career needs as “strong family managers” who successfully transfer these skills into organisational goals [

63]. In this qualitative research the principal researcher has adopted the strategy of personal ethnography (describing the research setting as a participant “insider”), informed by value premises reflecting both religion and nationalism.

This

autoethnographic approach may be particularly relevant for Palestine, in which a beleaguered social structure copes both with external attacks and internal change. My values and my approach to research have been strongly influenced by a critical incident in 2008 (described in detail by my partner, Wesam Abubaker [

50]). For 10 days, myself, my wife and our 2-year-old son were trapped in the rubble of our bombed house in Gaza. Here, as we sheltered beneath a kitchen table, my wife nursing our just-born second son, we survived 10 days of intermittent rocket barrage with little food or water, and no sanitation. Experiencing and contemplating this trauma has caused MAB to reorient himself in favour of pacifism (as did Abuelaish [

107] in 2011, when an Israeli tank killed his three children in Gaza).

MAB’s experience has led him to contemplate a future in which women and men (in Islam, and everywhere else) have equal power and equal opportunities in every sphere of society. His values as a researcher in Gaza reflect this “paradigm shift”, so that he has become an auto-ethnographer, a researcher with embedded values and moral purpose which are quite different from those of previous generations of Arab men. The researcher (MAB) experienced a “trauma of emotion” [

108] which resulted in a new consciousness of self and others, becoming an acutely sensitive observer of men and women in his culture. Alam [

82] commends the emergence of this new role of an “insider-ethnographer” who works for extended periods in complex Muslim organisations: “… the notion of field is not static but actively evolves as the research progresses. The field of research varies, at times even expands to sites which were not thought of earlier… ethnography fits well into the Muslim contexts as it unlocks aspects of life-worlds which are difficult to be captured by other methods of social inquiry.” (p. 4) This approach marries well with the understanding of social research offered by critical realism, and its approach to radical social change [

1].

Following Bhaskar, Frederiksen and Kringelum [

5] offer five key ways (italicised below) in which a critical realist understanding can be deployed in organisational research:

First: Applied critical realist ontology enables the researcher to delineate the phenomenon under study. In the present study we try and identify the structures (and the individual actors and their values) which surround and influence how WLB benefits are perceived and negotiated in the telecommunications sector of Gaza.

Second: Critical realism provides a meta-theoretical framing of the interplay between structures and actors that unfolds over time. The study has spanned the period 2014 to 2021, in which economic development in Gaza has been under travail. Remarkably, the two telecommunication companies have survived and continue to operate business and employment practices which generally meet Islamic requirements for ethical business practices. Within this framework there are interactions which reflect changing ideas of how power is exercised, and how women employees should be recruited, regarded and rewarded. Using WLB policy as a marker for these changes, we see how these policies reflect changes in the values of the wider social structure.

Third: Applied critical realist methodology offers explanatory value through the interplay of multiple empirical aspects. Various actors and agents at the level of the state, welfare laws, trade union pressures, employers’ conformity to public and private religious norms, desire for profit and prestige, international generosity, support and investment, the “masculine” desire of managers to be esteemed, the “feminine” desire of women to be rewarded and supported in their dual roles, as successful employees and as successful family managers, and the quite rapidly changing norms concerning male hegemony in the Arab world—all of these interact and address one another in “morphogenetic dialogue’, in which changes in values, power, status and prestige occur subtly (but often powerfully) in creating new social realities which influence organisational WLB policy and practice. The important changes have been those initiated by the subtle but determined activity of upwardly mobile women, acting within the general framework of Islamic normative behaviour.

Fourth: Applied critical realist epistemology accentuates the interpretative role of the researcher in developing knowledge. This is where the role of the individual researcher as auto-ethnographer has demonstrable importance. The researcher’s accounts of structures, and how individuals within those structures appear to undertake various roles, offer a perspective on levels of meaning, and the potentials for change.

Fifth: Critical realism bridges the gap between local and general knowledge. This account of the evolution of WLB policy and practice in a small nation enduring intermittent warfare offers insights into changes in business ethics and practices in the Arab world. The account should also offer useful insights and guides for international investors who partner with MENA organisations in the practice of business and commercial services, especially that are concerned with granting employment rights and benefits for female employees.

The researcher offers a case history from his ethnographic research which illustrates important social changes in the Arab world, in which Islam (e.g., through Shari’a law changes [

109]) act to acknowledge the equality of women with men, in a Qu’ranically derived manner: “Aminah was one of five adult siblings who live in a matrilocal dwelling (unusual but not rare in Gaza, where destruction of housing stock means that traditional patrilocal dwellings are often not available). All of the siblings are graduates, but only one of the three female siblings had outside employment (in telecoms). Approving this “outside” employment was a group-decision decided by her siblings, and they and her mother and sisters took on the role of child-carers for Aminah’s three children. However, her unemployed husband became resentful and violent, so he was expelled from the extended-family housing by the women, with limited access to his children. This decision was upheld by a local Shari’a court.” The point of this case history is to illustrate how multiple changes in structures, values and attitudes interact in producing crucial developments in previously conservative cultures. It also supports Abu-Lughod’s arguments (2010 and 2013) for ethnographic research which rejects Western stereotypes of “oppressed” Muslim women.

The researchers follow the inspirational, pacifist feminism of the American Jewish scholar Judith Butler [

12,

13,

110,

111], who, like Abu-Lughod [

14,

29], is fiercely critical of Western feminist stereotypes of the weakness of “oppressed” Muslim women. Butler [

111] describes the suffering of Gazan women as a dignifying experience, and she offers a rapprochement between Arab and Jewish feminists in her pacifist arguments for women-led solutions to international conflicts, such as that between Palestine and Israel [

110,

111]. Inspired by Butler’s ideas, we have used her writings as the intellectual “under-labourer” in our critical realist analysis.

There are clearly limitations to this research approach. As with many qualitative designs, it may be difficult for future researchers to replicate, and the results obtained may not be generalizable beyond a small number of Arabic countries. Parallel quantitative and qualitative studies should be undertaken in order to paint the fullest picture of ways forward for WLB policies and international investment, for a broader range of Arabic (and other) nations.