How Superhero Characters Shape Brand Alliances and Leverage the Local Brand: The Evidence from Indonesia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

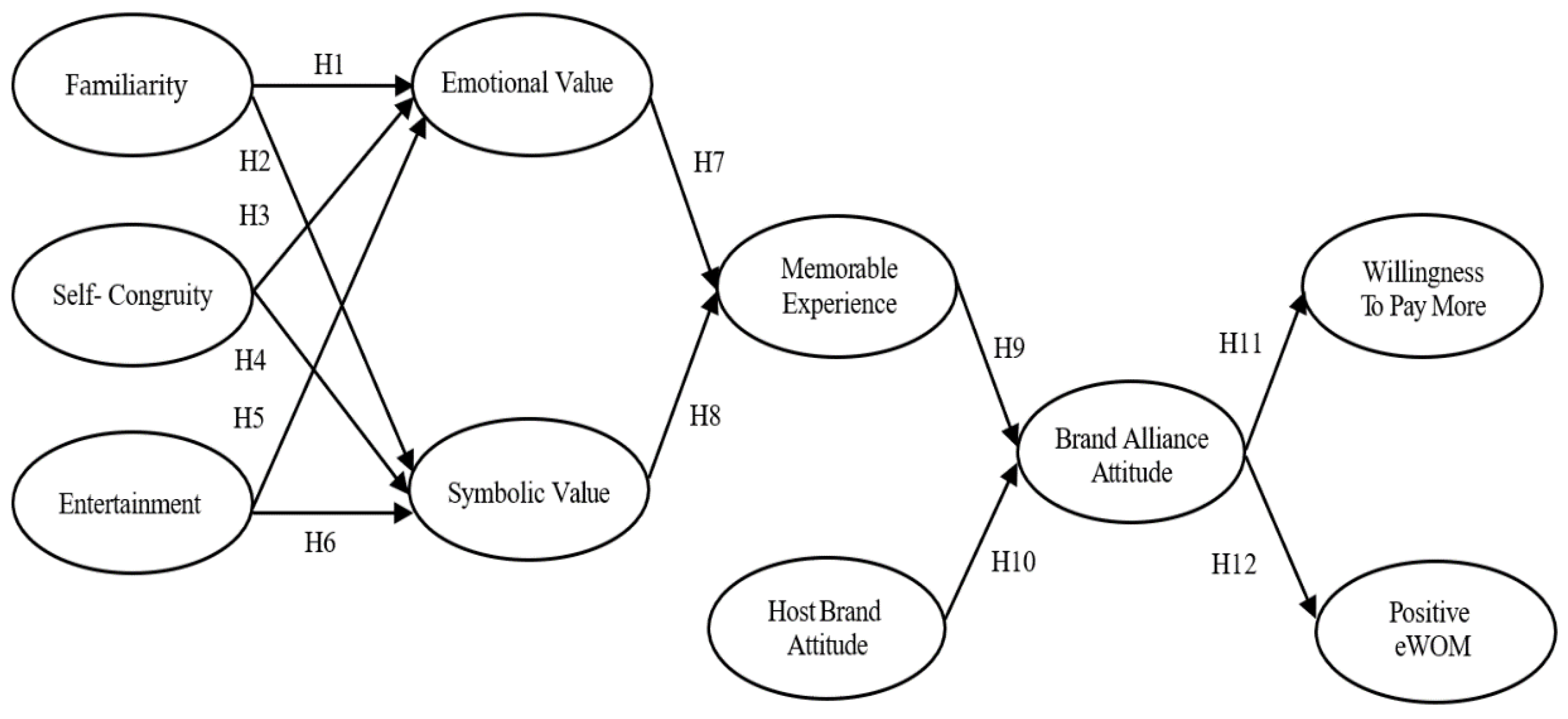

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. Emotional Value and Symbolic Value

3.2. Memorable Experience

3.3. Brand Alliance Attitude

4. Methods

4.1. Participants

4.2. Measurement

4.3. Analysis

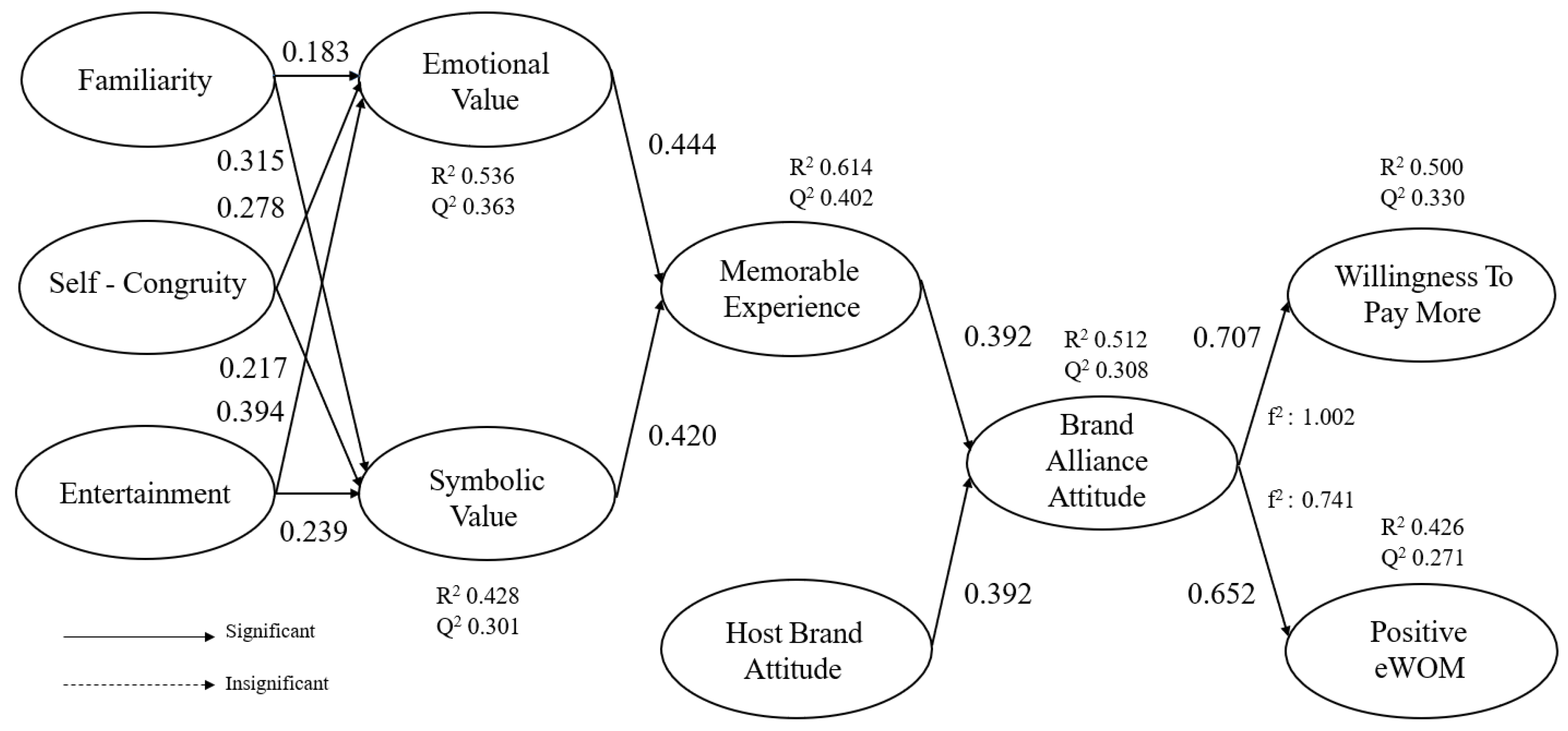

5. Results

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eury, M.; Misiroglu, G.; Sanderson, P. Superhero. Definition, Names, Movies, History, and Facts. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/art/superhero (accessed on 6 November 2021).

- Hammonds, K. The Globalization of Superheroes: Diffusion, Genre, and Cultural Adaptations. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021; ISBN 9780190228613. [Google Scholar]

- Beaty, B. Superhero Fan Service: Audience Strategies in the Contemporary Interlinked Hollywood Blockbuster. Inf. Soc. 2016, 32, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becko, L. Consumption of Superheroes: The Performances of Fans as Strategies of Involvement. Panic Discourse Interdiscip. J. 2019, 1, 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V. The Superhero Symbol: Media, Culture and Politics. New Rev. Film. Telev. Stud. 2021, 19, 112–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.; College, D. Strategic Brand Management, 4th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Atuahene-Gima, K.; Patterson, P.G. The Impact of Managerial Attitudes on Technology Licensing Performance. Eur. J. Mark. 1992, 26, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licensing International. The 2020 Global Licensing Industry Study; Licensing International Commissioned Brandar Consulting, LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Statista Leading Merchandise Licensors Worldwide 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/294111/leading-organizations-in-licensed-merchandise-worldwide/ (accessed on 8 November 2021).

- Bluemelhuber, C.; Carter, L.L.; Lambe, C.J. Extending the View of Brand Alliance Effects: An Integrative Examination of the Role of Country of Origin. Int. Mark. Rev. 2007, 24, 427–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Yan, R. Does Brand Partnership Create a Happy Marriage? The Role of Brand Value on Brand Alliance Outcomes of Partners. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 67, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johan Lanseng, E.; Erling Olsen, L. Brand Alliances: The Role of Brand Concept Consistency. Eur. J. Mark. 2012, 46, 1108–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonin, B.L.; Ruth, J.A. Is a Company Known by the Company It Keeps? Assessing the Spillover Effects of Brand Alliances on Consumer Brand Attitudes. J. Mark. Res. 1998, 35, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgarth, C. Evaluations of Co-brands and Spill-over Effects: Further Empirical Results. J. Mark. Commun. 2004, 10, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmig, B.; Huber, J.-A.; Leeflang, P. Explaining Behavioural Intentions toward Co-Branded Products. J. Mark. Manag. 2007, 23, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riley, D.; Charlton, N.; Wason, H. The Impact of Brand Image Fit on Attitude towards a Brand Alliance. Manag. Mark. 2015, 10, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ma, B.; Cheng, F.; Bu, J.; Jiang, J. Effects of Brand Alliance on Brand Equity. J. Contemp. Mark. Sci. 2018, 1, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, K.K.; Keller, K.L. The Effects of Ingredient Branding Strategies on Host Brand Extendibility. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammoh, B.S.; Voss, K.E.; Chakraborty, G. Consumer Evaluation of Brand Alliance Signals. Psychol. Mark. 2006, 23, 465–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruekert, R.W.; Ashkay, R.R. Brand Alliances as Signals of Product Quality. Available online: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/brand-alliances-as-signals-of-product-quality/ (accessed on 9 November 2021).

- Hegner, N.; Peixoto, G. NHH Brage: Can Brands Have Superheroes? A Study Investigating the Effects of Brand Alliances with Superhero Characters on the Evaluation of the Host Brand; Norwegian School of Economics: Bergen, Norway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Quan, H. The Relationship among Food Perceived Value, Memorable Tourism Experiences and Behaviour Intention: The Case of the Macao Food Festival. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2019, 19, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H. The Antecedents of Memorable Tourism Experiences: The Development of a Scale to Measure the Destination Attributes Associated with Memorable Experiences. Tour. Manag. 2014, 44, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. The Experiential Aspects of Consumption: Consumer Fantasies, Feelings, and Fun. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. Welcome to the Experience Economy. Available online: https://hbr.org/1998/07/welcome-to-the-experience-economy (accessed on 7 November 2021).

- Brakus, J.J.; Schmitt, B.H.; Zarantonello, L. Brand Experience: What Is It? How Is It Measured? Does It Affect Loyalty? J. Mark. 2009, 73, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yodpram, S.; Intalar, N. Conceptualizing EWOM, Brand Image, and Brand Attitude on Consumer’s Willingness to Pay in the Low-Cost Airline Industry in Thailand. Proceedings 2020, 39, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismagilova, E.; Rana, N.P.; Slade, E.L.; Dwivedi, Y.K. A Meta-Analysis of the Factors Affecting EWOM Providing Behaviour. Eur. J. Mark. 2021, 55, 1067–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, A. The Impact of Brand Familiarity, Customer Brand Engagement and Self-Identification on Word-of-Mouth. South Asian J. Bus. Stud. 2020, 10, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Brady, J.T. Consumers Willingness to Pay More for Character Licensed Merchandise. Master’s Thesis, Graduate School of Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Paasovaara, R.; Luomala, H.; Sandell, M. The Effects of Brand Familiarity and Consumer Value—Brand Symbolism (In) Congruity on Taste Perception. In The Customer is NOT Always Right? Marketing Orientationsin a Dynamic Business World; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 754–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aw, E.C.-X.; Flynn, L.R.; Chong, H.X. Antecedents and Consequences of Self-Congruity: Replication and Extension. J. Consum. Mark. 2019, 36, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, M.; Thapa, B. The Influence of Self-Congruity, Perceived Value, and Satisfaction on Destination Loyalty: A Case Study of the Korean DMZ. J. Herit. Tour. 2018, 13, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C.; Lin, Y.-C. What Drives Live-Stream Usage Intention? The Perspectives of Flow, Entertainment, Social Interaction, and Endorsement. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmashhara, M.G.; Soares, A.M. Entertain Me, I’ll Stay Longer! The Influence of Types of Entertainment on Mall Shoppers’ Emotions and Behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2019, 37, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, K.-W. The Antecedents and Consequences of Golf Tournament Spectators’ Memorable Brand Experiences. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tongeren, D.R.; Hibbard, R.; Edwards, M.; Johnson, E.; Diepholz, K.; Newbound, H.; Shay, A.; Houpt, R.; Cairo, A.; Green, J.D. Heroic Helping: The Effects of Priming Superhero Images on Prosociality. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolbec, P.-Y.; Chebat, J.-C. The Impact of a Flagship vs. a Brand Store on Brand Attitude, Brand Attachment and Brand Equity. J. Retail. 2013, 89, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Choe, J.Y.; Kim, H.M.; Kim, J.J. The Antecedents and Consequences of Memorable Brand Experience: Human Baristas versus Robot Baristas. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Cao, Z. Is Brand Alliance Always Beneficial to Firms? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovic, I.; Bossink, B.A.G.; van der Sijde, P.C.; Fong, C.Y.M. Why Are Consumers Willing to Pay More for Liquid Foods in Environmentally Friendly Packaging? A Dual Attitudes Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodrigue, C.S.; Biswas, A. Brand Alliance Dependency and Exclusivity: An Empirical Investigation. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2004, 13, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Chen, H. Impact of Consumers’ Corporate Social Responsibility-related Activities in Social Media on Brand Attitude, Electronic Word-of-mouth Intention, and Purchase Intention: A Study of Chinese Consumer Behavior. J. Consumer Behav. 2019, 18, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismagilova, E.; Slade, E.; Rana, N.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K. The Effect of Characteristics of Source Credibility on Consumer Behaviour: A Meta-Analysis. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- BPS Badan Pusat Statistik. Available online: https://www.bps.go.id/pressrelease/2021/01/21/1854/hasil-sensus-penduduk-2020.html (accessed on 7 November 2021).

- World Bank. World Bank Indonesia Overview: Development News, Research, Data. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/indonesia/overview#1 (accessed on 7 November 2021).

- Global Research, Insights & Analytics INSEAK Brand Health Check Indonesia; Warner Bros. Entertainment: Burbank, CA, USA, 2021; pp. 1–54.

- Fishbein, M. A Behavior Theory Approach to the Relations between Beliefs about an Object and the Attitude toward the Object; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Longwell, G.J. Managing Brand Equity: Capitalizing on the Value of a Brand Name: David A. Aaker, The Free Press, New York (1991). J. Bus. Res. 1994, 29, 247–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Managing Customer-Based Brand Equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. Kotler On…. Manag. Decis. 1991, 29, 4961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, B. Experiential Marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 15, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer Perceptions of Price, Quality, and Value: A Means-End Model and Synthesis of Evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Cofman, K.P. Perceived Quality: How Consumers View Stores and Merchandise. In Quality and Value in the Consumption Experience: Phaedrus Rides Again; Jacoby, J., Olson., J.C., Eds.; D.C. Heath and Company: Lexington, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Sheth, J.N.; Newman, B.I.; Gross, B.L. Why We Buy What We Buy: A Theory of Consumption Values. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer Perceived Value: The Development of a Multiple Item Scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; Macinnis, D.J.; Priester, J.; Eisingerich, A.B.; Iacobucci, D. Brand Attachment and Brand Attitude Strength: Conceptual and Empirical Differentiation of Two Critical Brand Equity Drivers. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hunt, S.A.; Miller, K.A. The Discourse of Dress and Appearance: Identity Talk and a Rhetoric of Review. Symb. Interact. 1997, 20, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Moore, W.L. Feature Interactions in Consumer Judgments of Verbal versus Pictorial Presentations. J. Consum. Res. 1981, 8, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, W.; Hutchinson, J.W.; Moore, D.; Nedungadi, P. Brand Familiarity and Advertising: Effects on the Evoked Set and Brand Preference. ACR N. Am. Adv. 1986, 13, 637–642. [Google Scholar]

- Alba, J.W.; Hutchinson, J.W. Dimensions of Consumer Expertise. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 13, 411–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, R.J.; Allen, C.T. Competitive Interference Effects in Consumer Memory for Advertising: The Role of Brand Familiarity. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beggan, J.K.; Brown, E.M. Association as a Psychological Justification for Ownership. J. Psychol. 1994, 128, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J.L.; Kostova, T.; Dirks, K.T. The State of Psychological Ownership: Integrating and Extending a Century of Research. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2003, 7, 84–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Choi, J.K.; Han, W.H.; Kim, J.H. The Influence of Users’ Spatial Familiarity on Their Emotional Perception of Space and Wayfinding Movement Patterns. Sensors 2021, 21, 2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.S.; Hass, C.J.; Fawver, B.; Lee, H.; Janelle, C.M. Emotional States Influence Forward Gait during Music Listening Based on Familiarity with Music Selections. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2019, 66, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirgy, M.J. Self-Concept in Consumer Behavior: A Critical Review. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennis, B.M.; Pruyn, A.T.H. You Are What You Wear: Brand Personality Influences on Consumer Impression Formation. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 634–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kressmann, F.; Sirgy, M.J.; Herrmann, A.; Huber, F.; Huber, S.; Lee, D.-J. Direct and Indirect Effects of Self-Image Congruence on Brand Loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frías-Jamilena, D.M.; Castañeda-García, J.A.; Del Barrio-García, S. Self-Congruity and Motivations as Antecedents of Destination Perceived Value: The Moderating Effect of Previous Experience. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bosshart, L.; Macconi, I. Media Entertainment; Centre for the Study of Communication and Culture: Santa Clara, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- McKee, A.; Collis, C.; Nitins, T.; Ryan, M.; Harrington, S.; Duncan, B.; Carter, J.; Luck, E.; Neale, L.; Butler, D.; et al. Defining Entertainment: An Approach. Creat. Ind. J. 2014, 7, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B. The Millennial Consumer in the Texts of Our Times: Experience and Entertainment. J. Macromark. 2000, 20, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S.S.; Kim, W.; Lee, M.J. The Impact of Advertising on Patrons’ Emotional Responses, Perceived Value, and Behavioral Intentions in the Chain Restaurant Industry: The Moderating Role of Advertising-Induced Arousal. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M.J. The Entertainment Economy: How Mega-Media Forces Are Transforming Our Lives; Penguin: London, UK, 1999; ISBN 9780140281750. [Google Scholar]

- Sit, J.; Merrilees, B.; Birch, D. Entertainment-seeking Shopping Centre Patrons: The Missing Segments. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2003, 31, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cupchik, G. The Role of Feeling in the Entertainment=Emotion Formula. J. Media Psychol. Theor. Methods Appl. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M.B.; Raney, A.A. Entertainment as Pleasurable and Meaningful: Identifying Hedonic and Eudaimonic Motivations for Entertainment Consumption. J. Commun. 2011, 61, 984–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Niehm, L.S. The Impact of Website Quality on Information Quality, Value, and Loyalty Intentions in Apparel Retailing. J. Interact. Mark. 2009, 23, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarantonello, L.; Schmitt, B.H. Using the Brand Experience Scale to Profile Consumers and Predict Consumer Behaviour. J. Brand Manag. 2010, 17, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaus, P.; Maklan, S. Towards a Better Measure of Customer Experience. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2013, 55, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coelho, F.J.F.; Bairrada, C.M.; de Matos Coelho, A.F. Functional Brand Qualities and Perceived Value: The Mediating Role of Brand Experience and Brand Personality. Psychol. Mark. 2020, 37, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-S.; Shin, D.-J.; Koo, D.-W. The Influence of Perceived Service Fairness on Brand Trust, Brand Experience and Brand Citizenship Behavior. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2603–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedmann, K.-P.; Labenz, F.; Haase, J.; Hennigs, N. The Power of Experiential Marketing: Exploring the Causal Relationships among Multisensory Marketing, Brand Experience, Customer Perceived Value and Brand Strength. J. Brand Manag. 2018, 25, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Wong, V.; Saunders, J.; Armstrong, G. Principles of Marketing, Fourth Europian Edition; Pearson: London, UK, 2005; ISBN 9780273684565. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.W.; Jun, S.Y.; Shocker, A.D. Composite Branding Alliances: An Investigation of Extension and Feedback Effects. J. Mark. Res. 1996, 33, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonin, B.L.; Ruth, J.A. Bundling as a Strategy for New Product Introduction: Effects on Consumers’ Reservation Prices for the Bundle, the New Product, and Its Tie-In. J. Bus. Res. 1995, 33, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, O.C.; Hartline, M.D. Marketing Strategy: Text and Cases; South-Western Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2014; ISBN 9781285170435. [Google Scholar]

- Stach, J. How Memorable Experiences Influence Brand Preference. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2017, 20, 394–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Kunkel, T. Beyond Brand Fit: The Influence of Brand Contribution on the Relationship between Service Brand Alliances and Their Parent Brands. J. Serv. Manag. 2019, 30, 252–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S.; Busser, J.; Cain, L. Impact of Experience on Emotional Well-Being and Loyalty. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 28, 427–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarantonello, L.; Schmitt, B.H. The Impact of Event Marketing on Brand Equity. Int. J. Advert. 2013, 32, 255–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lafferty, B.A.; Goldsmith, R.E.; Hult, G.T.M. The Impact of the Alliance on the Partners: A Look at Cause-Brand Alliances. Psychol. Mark. 2004, 21, 509–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cegarra, J.-J.; Michel, G. Co-Branding: Clarification Du Concept. Rech. Appl. Mark. 2001, 16, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K.; Lee, B.-K.; Lee, W.-N. The Effects of Country-of-Origin Fit on Cross-Border Brand Alliances. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2018, 30, 1259–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newmeyer, C.E.; Ruth, J.A. Good Times and Bad: Responsibility in Brand Alliances. Eur. J. Mark. 2020, 54, 448–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, D.B.; Laverie, D.A.; Wilcox, J.B. A Longitudinal Examination of the Effects of Retailer–Manufacturer Brand Alliances: The Role of Perceived Fit. J. Mark. Manag. 2010, 26, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, V.; Hollebeek, L.D. Higher Education Brand Alliances: Investigating Consumers’ Dual-Degree Purchase Intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3113–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samu, S.; Krishnan, H.S.; Smith, R.E. Using Advertising Alliances for New Product Introduction: Interactions between Product Complementarity and Promotional Strategies. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Ballester, E.; Hernández-Espallardo, M. Building Online Brands through Brand Alliances in Internet. Eur. J. Mark. 2008, 42, 954–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y. Evaluation of Co-branded Hotels in the Taiwanese Market: The Role of Brand Familiarity and Brand Fit. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 25, 346–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Tsai, H.-N.; Lee, Y.-C. The Effects of Product Categories, Brand Alliance Fitness and Personality Traits on Customer’s Brand Attitude and Purchase Intentions: A Case of Spotify. J. Stat. Manag. Syst. 2020, 23, 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. Managing Brand Equity; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991; ISBN 9780029001011. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, T.A.; James, M.D. Estimating Willingness to Pay from Survey Data: An Alternative Pre-Test-Market Evaluation Procedure. J. Mark. Res. 1987, 24, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A. Effect of Dealing Patterns on Consumer Perceptions of Deal Frequency and Willingness to Pay. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rao, A.R.; Bergen, M.E. Price Premium Variations as a Consequence of Buyers’ Lack of Information. J. Consum. Res. 1992, 19, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pelsmacker, P.; Driesen, L.; Rayp, G. Do Consumers Care about Ethics? Willingness to Pay for Fair-Trade Coffee. J. Consum. Aff. 2005, 39, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, C.; Koschate, N.; Hoyer, W.D. Do Satisfied Customers Really Pay More? A Study of the Relationship between Customer Satisfaction and Willingness to Pay. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priem, R.L. A Consumer Perspective on Value Creation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Ang, T.; Jancenelle, V.E. Willingness to Pay More for Green Products: The Interplay of Consumer Characteristics and Customer Participation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 45, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Fan, A.; He, Z.; Her, E. To Partner with Human or Robot? Designing Service Coproduction Processes for Willingness to Pay More. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haumann, T.; Quaiser, B.; Wieseke, J.; Rese, M. Footprints in the Sands of Time: A Comparative Analysis of the Effectiveness of Customer Satisfaction and Customer-Company Identification over Time. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 78–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.M.F.; Lam, D. The Role of Extraversion and Agreeableness Traits on Gen Y’s Attitudes and Willingness to Pay for Green Hotels. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 607–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.; Gupta, I.C.; Totala, N.K. Social Media Usage, Electronic Word of Mouth and Purchase-Decision Involvement. Asia Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2017, 9, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Walsh, G.; Gremler, D.D. Electronic Word-of-Mouth via Consumer-Opinion Platforms: What Motivates Consumers to Articulate Themselves on the Internet? J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickart, B.; Schindler, R.M. Internet Forums as Influential Sources of Consumer Information. J. Interact. Mark. 2001, 15, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, D.; Dewani, P.P. EWOM Credibility: A Comprehensive Framework and Literature Review. Online Inf. Rev. 2020, 45, 481–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.-Y.; Lin, C.A. Predicting the Effects of EWOM and Online Brand Messaging: Source Trust, Bandwagon Effect and Innovation Adoption Factors. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delafrooz, N.; Rahmati, Y.; Abdi, M. The Influence of Electronic Word of Mouth on Instagram Users: An Emphasis on Consumer Socialization Framework. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2019, 6, 1606973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkan, I.; Evans, C. The Influence of EWOM in Social Media on Consumers’ Purchase Intentions: An Extended Approach to Information Adoption. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 61, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godey, B.; Manthiou, A.; Pederzoli, D.; Rokka, J.; Aiello, G.; Donvito, R.; Singh, R. Social Media Marketing Efforts of Luxury Brands: Influence on Brand Equity and Consumer Behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5833–5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Sung, Y.; Kang, H. Brand Followers’ Retweeting Behavior on Twitter: How Brand Relationships Influence Brand Electronic Word-of-Mouth. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 37, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhidari, A.; Iyer, P.; Paswan, A. Personal Level Antecedents of EWOM and Purchase Intention, on Social Networking Sites. J. Cust. Behav. 2015, 14, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.-C.; Sung, Y. Using a Consumer Socialization Framework to Understand Electronic Word-of-Mouth (EWOM) Group Membership among Brand Followers on Twitter. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2015, 14, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Gupta, P. Emotional Expressions in Online User Reviews: How They Influence Consumers’ Product Evaluations. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.-Y.; Perks, H. Effects of Consumer Perceptions of Brand Experience on the Web: Brand Familiarity, Satisfaction and Brand Trust. J. Consum. Behav. 2005, 4, 438–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassler, P.; Wang, L.; Hung, K. Identity and Destination Branding among Residents: How Does Brand Self-congruity Influence Brand Attitude and Ambassadorial Behavior? Int. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Grewal, D.; Mangleburg, T.F.; Park, J.-O.; Chon, K.-S.; Claiborne, C.B.; Johar, J.S.; Berkman, H. Assessing the Predictive Validity of Two Methods of Measuring Self-Image Congruence. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1997, 25, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathwick, C.; Malhotra, N.; Rigdon, E. Experiential Value: Conceptualization, Measurement and Application in the Catalog and Internet Shopping Environment. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van-Tien Dao, W.; Nhat Hanh Le, A.; Ming-Sung Cheng, J.; Chao Chen, D. Social Media Advertising Value: The Case of Transitional Economies in Southeast Asia. Int. J. Advert. 2014, 33, 271–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, H. Personal Value vs. Luxury Value: What Are Chinese Luxury Consumers Shopping for When Buying Luxury Fashion Goods? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sthapit, E.; Coudounaris, D.N.; Björk, P. Extending the Memorable Tourism Experience Construct: An Investigation of Memories of Local Food Experiences. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2019, 19, 333–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgeson, J.G.; Supphellen, M. A Conceptual and Measurement Comparison of Self-Congruity and Brand Personality: The Impact of Socially Desirable Responding. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2004, 46, 205–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.K.; Zhuang, G.; Li, S. Will Consumers Pay More for Efficient Delivery? An Empirical Study of What Affects E-Customers’ Satisfaction and Willingness to Pay on Online Shopping in Bangladesh. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Serra-Cantallops, A.; Ramón Cardona, J.; Salvi, F. Antecedents of Positive EWOM in Hotels. Exploring the Relative Role of Satisfaction, Quality and Positive Emotional Experiences. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 3457–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Homburg, C., Klarmann, M., Vomberg, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–40. ISBN 9783319055428. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, M.A.; Ramayah, T.; Cheah, J.-H.; Ting, H.; Chuah, F.; Cham, T.H. Pls-Sem Statistical Programs: A Review. J. Appl. Struct. Equ. Modeling 2021, 5, i–xiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzl, C.; Roldan, J.L.; Cepeda, G. Mediation Analysis in Partial Least Squares Path Modeling: Helping Researchers Discuss More Sophisticated Models. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 1849–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinali, S.; Travaglini, M.; Giovannetti, M. Increasing Brand Orientation and Brand Capabilities Using Licensing: An Opportunity for SMEs in International Markets. J. Knowl. Econ. 2019, 10, 1808–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas, F.J.; Nicolau, J.L.; Calderón, A. Brand Alliances and Stock Reactions. J. Bus. Bus. Mark. 2021, 28, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinko, R.; de Burgh-Woodman, H.; Furner, Z.Z.; Kim, S.J. Seeing Is Believing: The Effects of Images on Trust and Purchase Intent in EWOM for Hedonic and Utilitarian Products. J. Organ. End User Comput. 2021, 33, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Variables | Sample | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (%) | ||

| Gender | Male | 505 | 46 |

| Female | 594 | 54 | |

| Age | 17–24 years | 360 | 33 |

| 25–30 years | 325 | 30 | |

| 31–40 years | 324 | 29 | |

| >40 years | 90 | 8 | |

| Occupation | Student | 351 | 32 |

| Employee | 408 | 37 | |

| Entrepreneur | 176 | 16 | |

| Professional | 77 | 7 | |

| Housewife | 46 | 4 | |

| Freelancer | 29 | 3 | |

| Others | 12 | 1 | |

| Monthly Household Expenditure | USD 104.07–210.10 | 317 | 29 |

| USD 210.10–350.17 | 458 | 42 | |

| USD 350.17–525.26 | 145 | 13 | |

| >USD 525.26 | 179 | 16 | |

| Variable | Indicator | Outer Loading | CA | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Familiarity | FAM1: I can recognize superhero characters from movies | 0.882 | 0.771 | 0.896 | 0.812 |

| FAM2: I am informed about Superhero characters | 0.920 | ||||

| Self-congruity | SC1: I feel there is a match between my personality and the superhero character personality | 0.796 | 0.767 | 0.865 | 0.682 |

| SC2: Superhero characters reflect my personality | 0.845 | ||||

| SC3: I find that there is a part of the superhero character that I want to be a part of my personality | 0.836 | ||||

| Entertainment | ENT2: I find that superhero characters excite me | 0.728 | 0.771 | 0.896 | 0.812 |

| ENT3: I feel happy when I see superhero characters | 0.760 | ||||

| ENT4: Superhero characters spark joy | 0.783 | ||||

| ENT5: Superhero characters are more interesting than other characters | 0.782 | ||||

| Emotional value | EV1: I enjoy local brand products with superhero character logos or images | 0.823 | 0.768 | 0.866 | 0.683 |

| EV3: I enjoy using local brand products with superhero character logos or images | 0.826 | ||||

| EV4: Using local brand products with superhero characters makes me feel better | 0.831 | ||||

| Symbolic value | SV1: I become the center of attention when I use local brand products with superhero characters | 0.790 | 0.917 | 0.935 | 0.707 |

| SV2: Local brand products with superhero characters attract attention | 0.791 | ||||

| SV3: Local brand products with superhero characters symbolize my social status | 0.868 | ||||

| SV4: Wearing local brand products with superhero characters makes me different | 0.852 | ||||

| SV5: I feel that I look successful when I use local brand products with superhero characters | 0.868 | ||||

| SV6: I feel more confident when buying local brand products with superhero characters | 0.870 | ||||

| Memorable experience | ME1: I have good memories of using local brand products with superhero characters | 0.785 | 0.828 | 0.886 | 0.660 |

| ME3: I never forget local brand products with superhero characters that I have used | 0.819 | ||||

| ME4: I can remember local brand products with superhero characters that I have used | 0.804 | ||||

| ME5: I can remember memorable moments when I used local brand products with superhero characters | 0.840 | ||||

| Host brand attitude | HBA1: I like this local brand product | 0.714 | 0.755 | 0.845 | 0.577 |

| HBA2: I have a good impression of this local brand product | 0.803 | ||||

| HBA3: This local brand product is easy to love | 0.775 | ||||

| HBA4: I like to use local brand products | 0.742 | ||||

| Brand alliance attitude | BAA1: Local brand products in collaboration with superhero licenses are more attractive | 0.734 | 0.786 | 0.862 | 0.609 |

| BAA2: Local brand products in collaboration with superhero licenses are more unique | 0.808 | ||||

| BAA3: Local brand products in collaboration with superhero licenses have a better image | 0.780 | ||||

| BAA4: Local brand products in collaboration with superhero licenses have a superior impression | 0.799 | ||||

| Willingness to pay more | WTPM1: I am willing to pay more for local brand products with a genuine superhero license | 0.804 | 0.831 | 0.888 | 0.664 |

| WTPM2: I am willing to pay more for local brand products with an official superhero license. | 0.835 | ||||

| WTPM3: I do not mind paying more for a local brand product with a superhero license in regard to the quality assurance | 0.820 | ||||

| WTPM4: I do not mind paying more for local brand products with a superhero license to support local brands | 0.801 | ||||

| Electronic Word of Mouth | EWOM1: I am willing to write positive comments about local brand products with superhero licenses on social media | 0.788 | 0.812 | 0.876 | 0.640 |

| EWOM2: I am willing to share positive content about local brand products with a superhero license on social media | 0.814 | ||||

| EWOM3: I am willing to post positive comments about local brand products with superhero characters on social media | 0.804 | ||||

| EWOM4: I will recommend local brand products with superhero characters on my social media accounts | 0.793 |

| Variable | Brand Alliance Attitude | Positive eWOM | Emotional Value | Entertainment | Familiarity | Host Brand Attitude | Memorable Experience | Self-congruity | Symbolic Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive eWOM | 0.816 | ||||||||

| Emotional value | 0.883 | 0.840 | |||||||

| Entertainment | 0.772 | 0.756 | 0.848 | ||||||

| Familiarity | 0.673 | 0.656 | 0.718 | 0.634 | |||||

| Host brand attitude | 0.844 | 0.893 | 0.829 | 0.803 | 0.609 | ||||

| Memorable experience | 0.805 | 0.825 | 0.894 | 0.742 | 0.734 | 0.829 | |||

| Self-congruity | 0.718 | 0.729 | 0.826 | 0.788 | 0.832 | 0.707 | 0.765 | ||

| Symbolic value | 0.677 | 0.645 | 0.765 | 0.618 | 0.675 | 0.621 | 0.808 | 0.670 | |

| Willingness to pay more | 0.874 | 0.812 | 0.804 | 0.743 | 0.663 | 0.794 | 0.743 | 0.684 | 0.651 |

| No. | Hypothesis | Standardized Coefficient | T-Statistics | p-Value | Significance | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Familiarity → emotional value | 0.183 | 5.446 | 0.000 | Significant * | Hypothesis supported |

| H2 | Familiarity → symbolic value | 0.314 | 9.986 | 0.000 | Significant * | Hypothesis supported |

| H3 | Self-congruity → emotional value | 0.278 | 7.905 | 0.000 | Significant * | Hypothesis supported |

| H4 | Self- congruity → symbolic value | 0.216 | 6.074 | 0.000 | Significant * | Hypothesis supported |

| H5 | Entertainment → emotional value | 0.393 | 10.603 | 0.000 | Significant * | Hypothesis supported |

| H6 | Entertainment → symbolic value | 0.238 | 6.755 | 0.000 | Significant * | Hypothesis supported |

| H7 | Emotional value → memorable experience | 0.444 | 14.235 | 0.000 | Significant * | Hypothesis supported |

| H8 | Symbolic value → memorable experience | 0.420 | 13.710 | 0.000 | Significant * | Hypothesis supported |

| H9 | Memorable experience → brand alliance attitude | 0.392 | 9.919 | 0.000 | Significant * | Hypothesis supported |

| H10 | Host brand attitude → brand alliance attitude | 0.392 | 10.110 | 0.000 | Significant * | Hypothesis supported |

| H11 | Brand alliance attitude → willingness to pay more | 0.707 | 32.958 | 0.000 | Significant * | Hypothesis supported |

| H12 | Brand alliance attitude → positive eWOM | 0.652 | 24.278 | 0.000 | Significant * | Hypothesis supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Monika, M.; Antonio, F. How Superhero Characters Shape Brand Alliances and Leverage the Local Brand: The Evidence from Indonesia. Businesses 2022, 2, 33-53. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses2010003

Monika M, Antonio F. How Superhero Characters Shape Brand Alliances and Leverage the Local Brand: The Evidence from Indonesia. Businesses. 2022; 2(1):33-53. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses2010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleMonika, Monika, and Ferdi Antonio. 2022. "How Superhero Characters Shape Brand Alliances and Leverage the Local Brand: The Evidence from Indonesia" Businesses 2, no. 1: 33-53. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses2010003

APA StyleMonika, M., & Antonio, F. (2022). How Superhero Characters Shape Brand Alliances and Leverage the Local Brand: The Evidence from Indonesia. Businesses, 2(1), 33-53. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses2010003