Principal Component and Multiple Linear Regression Analysis for Predicting Strength in Fiber-Reinforced Cement Mortars

Abstract

1. Introduction

| Sample No. | Sand (g) | Cement (g) | W/C Ratio | Volume of Fibers (%) | Fiber Length (mm) | Fiber Diameter (mm) | Density of Fibers (kg/m3) | Tensile Strength of Fibers (N/mm2) | Compressive Strength (N/mm2) | Flexural Strength (N/mm2) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1727 | 513 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8.68 | 1.93 | [25] |

| 2 | 1727 | 513 | 0.5 | 5 | 10 | 0.31 | 900 | 415 | 14.68 | 2.03 | |

| 3 | 1727 | 513 | 0.5 | 2 | 10 | 0.31 | 900 | 415 | 26.82 | 9.93 | |

| 4 | 1727 | 513 | 0.5 | 1 | 10 | 0.31 | 900 | 415 | 16.83 | 7.73 | |

| 5 | 1727 | 513 | 0.5 | 10 | 10 | 0.13 | 115 | 390 | 4.40 | 1.39 | |

| 6 | 1727 | 513 | 0.5 | 4 | 35 | 0.9 | 7850 | 1100 | 10.33 | 3.22 | |

| 7 | 1727 | 513 | 0.5 | 2 | 35 | 0.9 | 7850 | 1100 | 17.88 | 6.85 | |

| 8 | 1727 | 513 | 0.5 | 1 | 35 | 0.9 | 7850 | 1100 | 15.22 | 5.08 | |

| 9 | 1727 | 513 | 0.5 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 1010 | 250 | 15.86 | 8.80 | |

| 10 | 1727 | 513 | 0.5 | 2 | 10 | 1 | 1010 | 250 | 17.24 | 3.32 | |

| 11 | 1727 | 513 | 0.5 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 1010 | 250 | 15.34 | 2.81 | |

| 12 | 1727 | 513 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 10 | 1 | 1010 | 250 | 7.13 | 1.80 | |

| 13 | 1727 | 513 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 10 | 0.25 | 1400 | 222 | 25.21 | 10.21 | |

| 14 | 1727 | 513 | 0.5 | 1 | 10 | 0.25 | 1400 | 222 | 23.00 | 2.69 | |

| 15 | 1727 | 513 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 10 | 0.25 | 1400 | 222 | 9.71 | 1.73 | |

| 16 | 1727 | 513 | 0.5 | 2 | 25 | 0.2 | 940 | 413 | 14.13 | 1.20 | |

| 17 | 1727 | 513 | 0.5 | 1 | 25 | 0.2 | 940 | 413 | 14.57 | 0.75 | |

| 18 | 1727 | 513 | 0.5 | 8 | 20 | 0.15 | 145 | 206 | 7.08 | 2.49 | |

| 19 | 1727 | 513 | 0.5 | 5 | 20 | 0.15 | 145 | 206 | 8.22 | 1.75 | |

| 20 | 2308 | 450 | 0.98 | 1 | 12 | 0.31 | 910 | 0.77 | 13.00 | 2.80 | [26] |

| 21 | 2308 | 450 | 0.98 | 2 | 12 | 0.31 | 910 | 0.77 | 9.00 | 2.70 | |

| 22 | 2308 | 450 | 0.98 | 1 | 12 | 0.2 | 1300 | 230 | 15.50 | 3.90 | |

| 23 | 2308 | 450 | 0.98 | 2 | 12 | 0.2 | 1300 | 230 | 17.70 | 3.80 | |

| 24 | 2308 | 450 | 0.98 | 1 | 12 | 0.3 | 1580 | 728 | 15.60 | 3.30 | |

| 25 | 2308 | 450 | 0.98 | 2 | 12 | 0.3 | 1580 | 728 | 7.80 | 2.30 | |

| 26 | 430 | 170 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 32.25 | 7.79 | [27] |

| 27 | 420 | 160 | 0.55 | 0.414 | 5 | 0.2 | 1518 | 215 | 24.24 | 5.05 | |

| 28 | 420 | 165 | 0.6 | 0.415 | 10 | 0.2 | 1518 | 215 | 26.75 | 5.83 | |

| 29 | 420 | 165 | 0.6 | 0.418 | 30 | 0.2 | 1518 | 215 | 26.16 | 6.29 | |

| 30 | 410 | 150 | 0.65 | 0.803 | 5 | 0.2 | 1518 | 215 | 14.68 | 3.91 | |

| 31 | 410 | 150 | 0.5 | 0.808 | 10 | 0.2 | 1518 | 215 | 18.03 | 4.13 | |

| 32 | 415 | 160 | 0.5 | 0.819 | 30 | 0.2 | 1518 | 215 | 21.83 | 5.09 | |

| 33 | 400 | 140 | 0.65 | 1.178 | 5 | 0.2 | 1518 | 215 | 10.79 | 3.06 | |

| 34 | 410 | 150 | 0.6 | 1.191 | 10 | 0.2 | 1518 | 215 | 13.97 | 3.73 | |

| 35 | 415 | 150 | 0.6 | 1.211 | 30 | 0.2 | 1518 | 215 | 17.79 | 4.46 | |

| 36 | 410 | 150 | 0.6 | 1.526 | 5 | 0.2 | 1518 | 215 | 6.03 | 2.39 | |

| 37 | 410 | 150 | 0.6 | 1.544 | 10 | 0.2 | 1518 | 215 | 8.40 | 2.72 | |

| 38 | 400 | 150 | 0.65 | 1.584 | 30 | 0.2 | 1518 | 215 | 10.15 | 3.61 | |

| 39 | 1197 | 400 | 0.49 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33.00 | 3.40 | [28] |

| 40 | 1173 | 400 | 0.52 | 0.5 | 20 | 0.2 | 1160 | 275 | 30.00 | 3.10 | |

| 41 | 1157 | 400 | 0.54 | 1 | 20 | 0.2 | 1160 | 275 | 25.00 | 2.60 | |

| 42 | 1127 | 400 | 0.55 | 2 | 20 | 0.2 | 1160 | 275 | 20.00 | 1.70 | |

| 43 | 2000 | 1000 | 0.33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 39.44 | 4.13 | [29] |

| 44 | 2000 | 1000 | 0.33 | 0.25 | 4.48 | 0.29 | 1500 | 750 | 36.22 | 3.78 | |

| 45 | 2000 | 1000 | 0.33 | 0.25 | 5.22 | 0.25 | 1500 | 690 | 31.03 | 2.97 | |

| 46 | 2000 | 1000 | 0.33 | 0.25 | 6.84 | 0.13 | 1440 | 230 | 37.07 | 3.65 | |

| 47 | 1658 | 603 | 0.35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 75.00 | 14.90 | [30] |

| 48 | 1658 | 603 | 0.4 | 3 | 60 | 0.2 | 1300 | 222 | 77.00 | 15.40 | |

| 49 | 1658 | 603 | 0.45 | 6 | 60 | 0.2 | 1300 | 222 | 78.60 | 16.70 | |

| 50 | 1658 | 603 | 0.5 | 9 | 60 | 0.2 | 1300 | 222 | 70.00 | 16.00 | |

| 51 | 1658 | 603 | 0.55 | 12 | 60 | 0.2 | 1300 | 222 | 44.00 | 14.00 | |

| 52 | 1658 | 603 | 0.6 | 15 | 60 | 0.2 | 1300 | 222 | 28.04 | 13.80 |

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

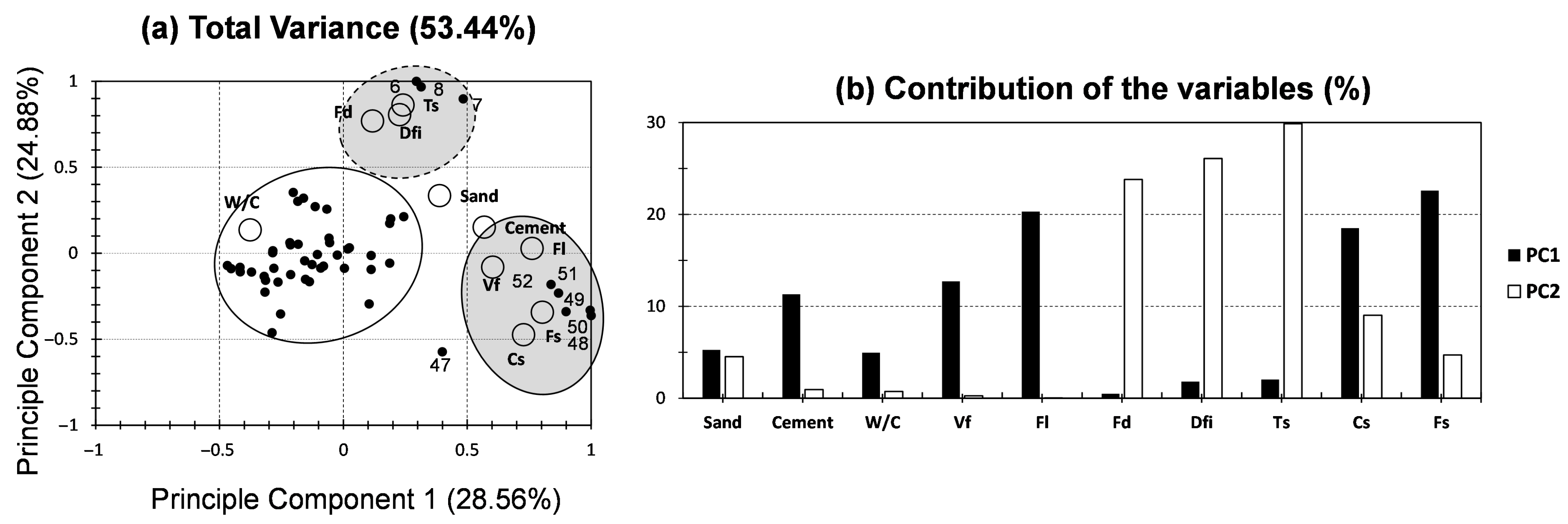

3.1. Application of PCA for Cementitious Materials

3.1.1. PCA for the Entire Dataset

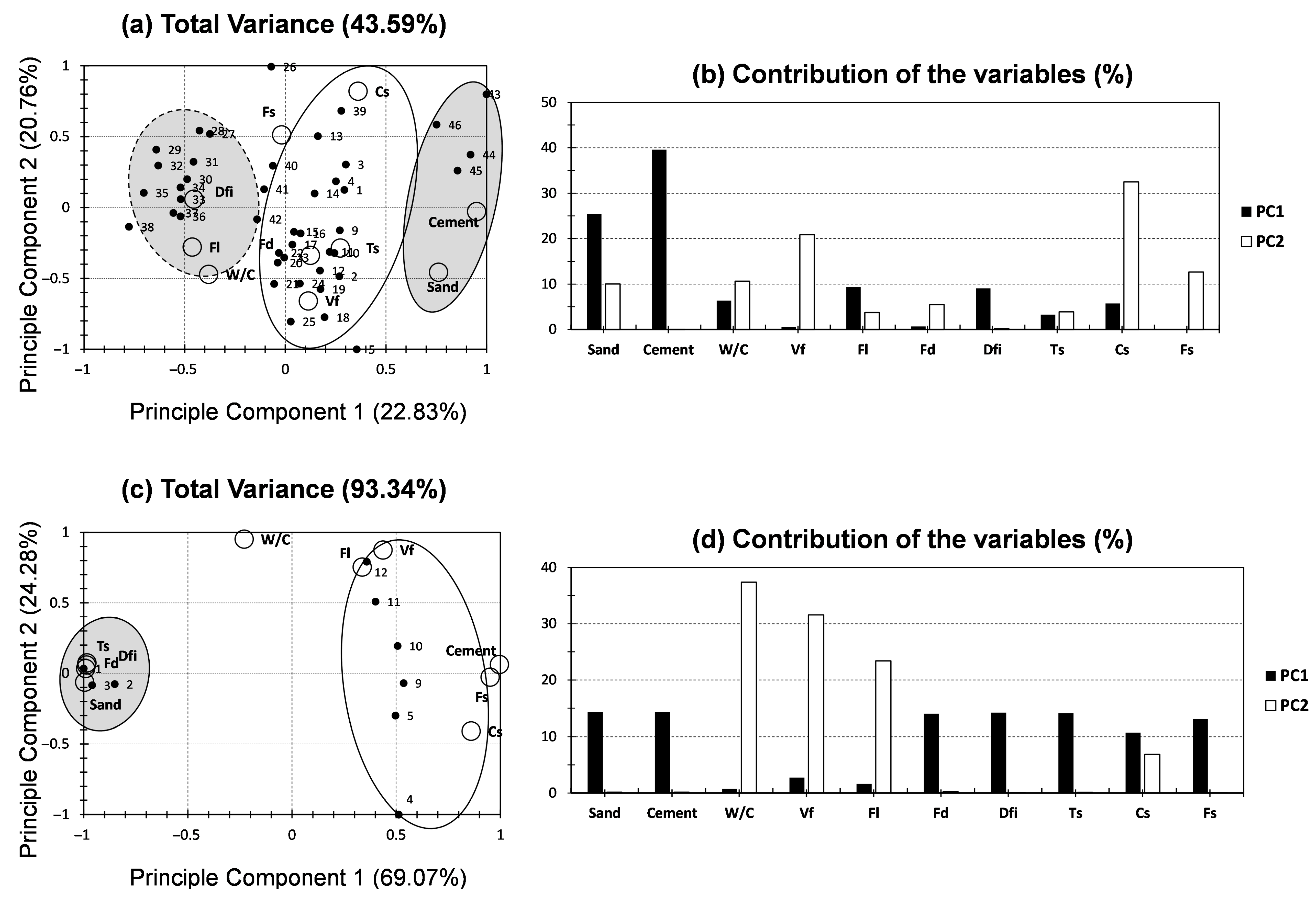

3.1.2. PCA: Dataset Segregation Approach

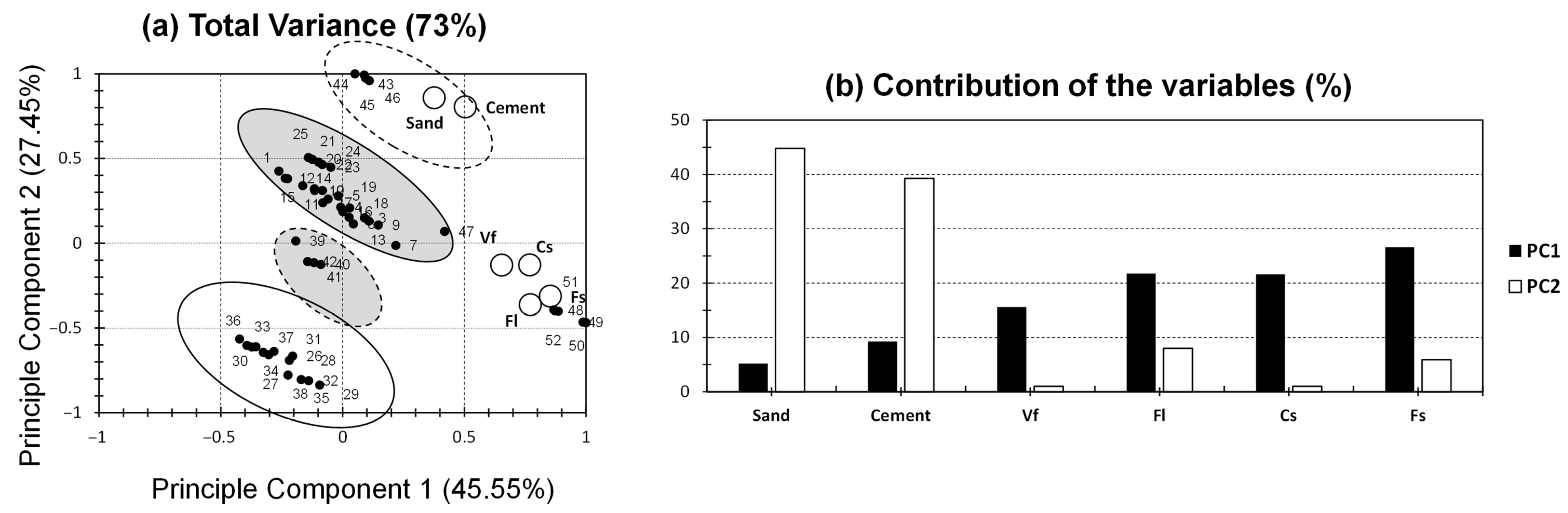

3.2. MLR: A PCA-Driven Approach

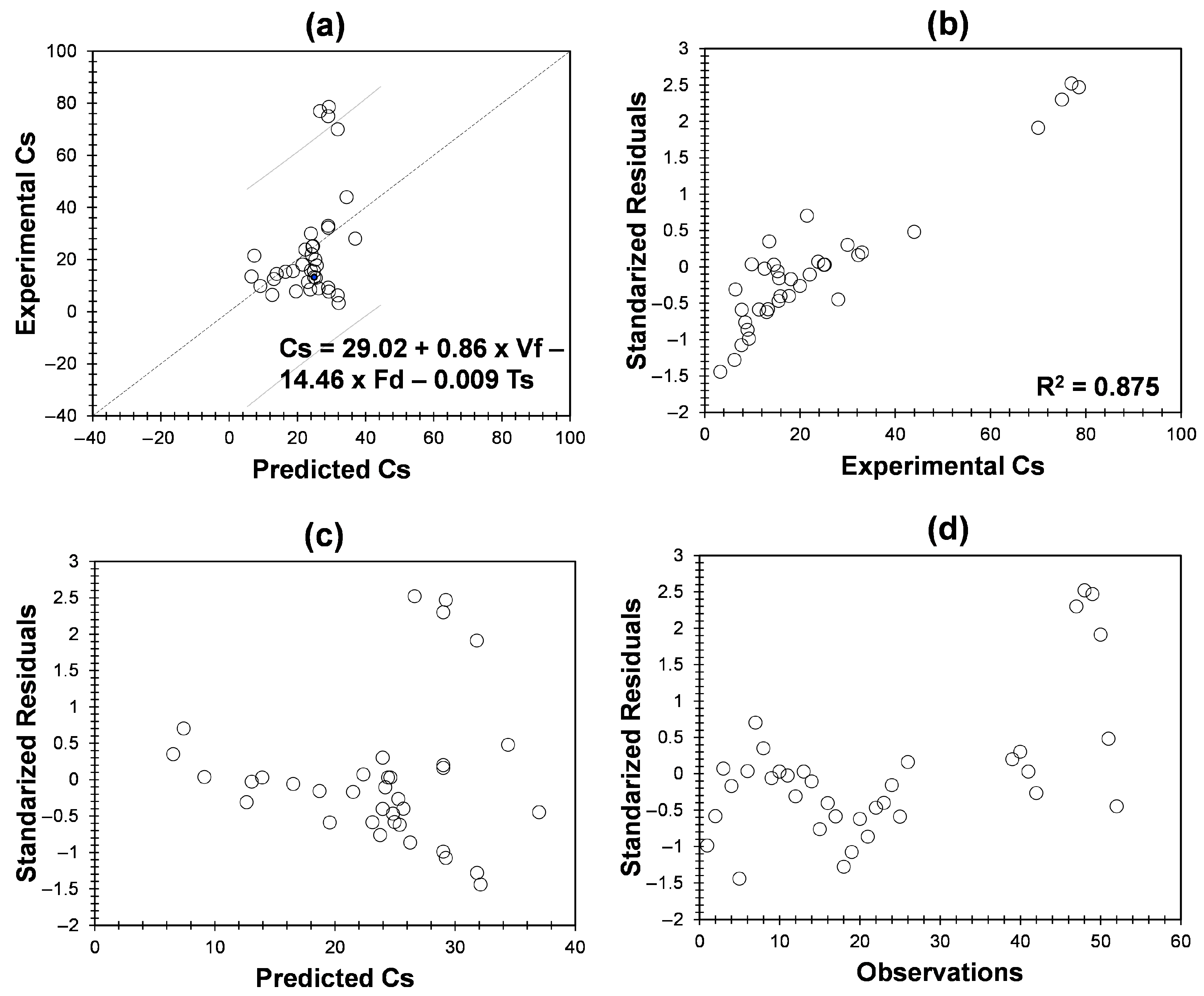

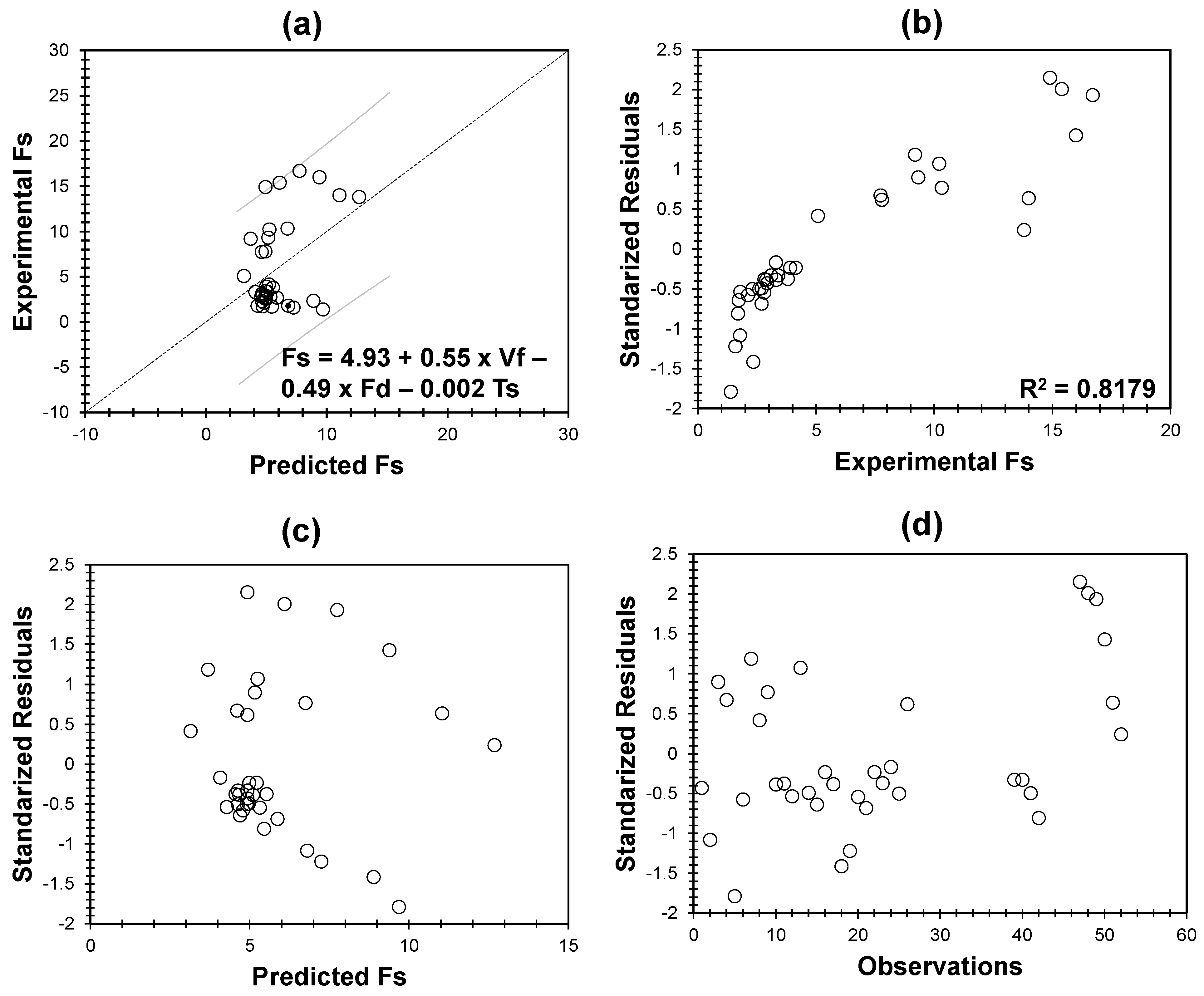

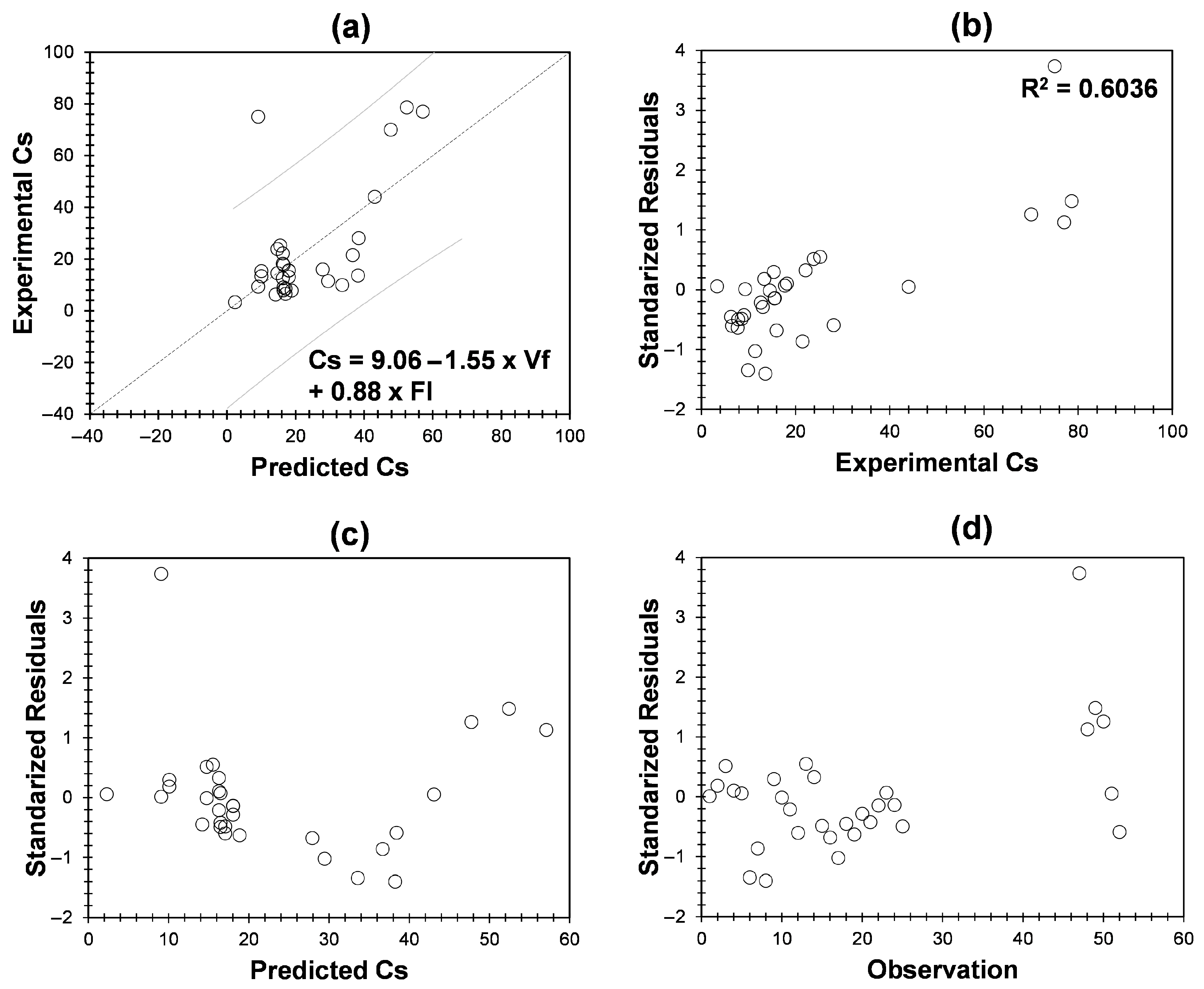

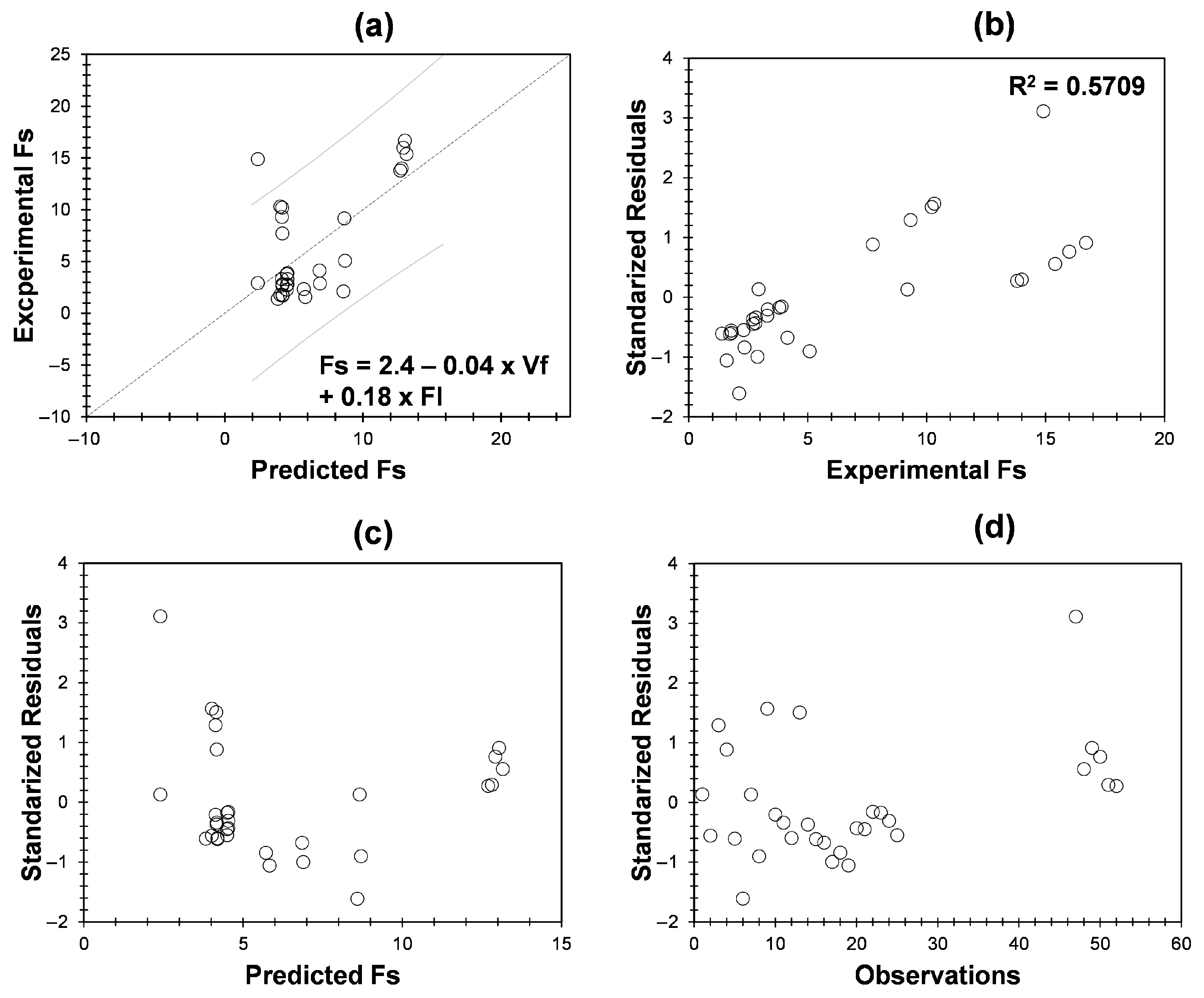

3.2.1. Application of MLR and Residual Analysis for Data Separation Approach

3.2.2. Application of MLR and Residual Analysis for Variables Exclusion Approach

3.3. Model Validation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pacheco-Torgal, F.; Jalali, S. Cementitious Building Materials Reinforced with Vegetable Fibres: A Review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, A.V.; Pantazopoulou, S.J. Effect of Fiber Length and Surface Characteristics on the Mechanical Properties of Cementitious Composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 125, 1216–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başsürücü, M.; Fenerli, C.; Kına, C.; Akbaş, Ş.D. Effect of Fiber Type, Shape and Volume Fraction on Mechanical and Flexural Properties of Concrete. J. Sustain. Constr. Mater. Technol. 2022, 7, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Meng, W.; Xu, M.; Li, V.C.; Bao, Y. Predicting Mechanical Properties of High-Performance Fiber-Reinforced Cementitious Composites by Integrating Micromechanics and Machine Learning. Materials 2021, 14, 3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, F.; Shafighfard, T.; Yoo, D.Y. Data-Driven Modeling of Mechanical Properties of Fiber-Reinforced Concrete: A Critical Review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2024, 31, 2049–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Jiao, M.; Ling, Y. Fracture Models and Effect of Fibers on Fracture Properties of Cementitious Composites—A Review. Materials 2020, 13, 5495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belyakov, N.; Smirnova, O.; Alekseev, A.; Tan, H. Numerical Simulation of the Mechanical Behavior of Fiber-Reinforced Cement Composites Subjected to Dynamic Loading. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhan, A.H.; Dawson, A.R.; Thom, N.H. Recycled Hybrid Fiber-Reinforced & Cement-Stabilized Pavement Mixtures: Tensile Properties and Cracking Characterization. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 179, 488–499. [Google Scholar]

- Decky, M.; Papanova, Z.; Juhas, M.; Kudelcikova, M. Evaluation of the Effect of Average Annual Temperatures in Slovakia between 1971 and 2020 on Stresses in Rigid Pavements. Land 2022, 11, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentur, A.; Mindess, S. Fibre Reinforced Cementitious Composites; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, N.H.; Liu, X.R.; Sun, J. Experimental Study of Crack Resistance for Multi Scale Polypropylene Fiber Reinforced Concrete. J. China Coal Soc. 2012, 37, 1304–1309. [Google Scholar]

- Ajwad, A.; Ilyas, U.; Muzammal, L.; Umer, A.; Haider, S.M. Evaluation of Strength Parameters of Plain and Reinforced Concrete with the Addition of Polypropylene Fibers. Mehran Univ. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2024, 43, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, T.; Zhao, Y.; Jin, D.; Xu, F. Prediction of Compressive and Flexural Strength of Coal Gangue-Based Geopolymer Using Machine Learning Method. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 44, 112076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.R.; Silva, J.B.L.P.E.; Gachet, L.A.; Santos, A.C.D.; Lintz, R.C.C. Evaluation of the Addition of Polypropylene (PP) Fibers in Self-Compacting Concrete (SCC) to Control Cracking and Plastic Shrinkage between Different Methods. Mater. Res. 2023, 26, e20220567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazıcı, Ş.; İnan, G.; Tabak, V. Effect of Aspect Ratio and Volume Fraction of Steel Fiber on the Mechanical Properties of SFRC. Constr. Build. Mater. 2007, 21, 1250–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobasher, B.; Li, C.Y. Mechanical Properties of Hybrid Cement-Based Composites. ACI Mater. J. 1996, 93, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, D.Y.; Banthia, N.; Yoon, Y.S. Predicting the Flexural Behavior of Ultra-High-Performance Fiber-Reinforced Concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 74, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jóźwiak-Niedźwiedzka, D.; Fantilli, A.P. Wool-Reinforced Cement Based Composites. Materials 2020, 13, 3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korjenic, A.; Petránek, V.; Zach, J.; Hroudová, J. Development and Performance Evaluation of Natural Thermal-Insulation Materials Composed of Renewable Resources. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 2518–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.K.; Kim, M.O.; Kim, D.J. Pullout Behavior of Recycled Waste Fishing Net Fibers Embedded in Cement Mortar. Materials 2020, 13, 4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.K.; Kim, D.J.; Kim, M.O. Mechanical Behavior of Waste Fishing Net Fiber-Reinforced Cementitious Composites Subjected to Direct Tension. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 33, 101622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavami, K. Bamboo as Reinforcement in Structural Concrete Elements. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2005, 27, 637–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, R.P.; Baldacchino, O.; Ferrara, L. Early Age Performance and Mechanical Characteristics of Recycled PET Fibre Reinforced Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 108, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Liu, A.; Sou, H.; Chouw, N. Mechanical and Dynamic Properties of Coconut Fibre Reinforced Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 30, 814–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMuhanna, M.; AlSenan, R.; Mustafaraj, E.; Luga, E.; Corradi, M. Fibre Reinforcement of Cement Mortars for Reinforcement of Masonry Buildings: An Experimental Investigation. J. Build. Rehabil. 2024, 9, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, J.R.; Bochen, J.; Gołaszewska, M. Experimental Studies on the Effect of Natural and Synthetic Fibers on Properties of Fresh and Hardened Mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 347, 128550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, A.; Stochino, F.; Frattolillo, A.; Valdes, M.; Mancusi, G.; Martinelli, E. Jute Fiber-Reinforced Mortars: Mechanical Response and Thermal Performance. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 66, 105888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozerkan, N.G.; Ahsan, B.; Mansour, S.; Iyengar, S.R. Mechanical Performance and Durability of Treated Palm Fiber Reinforced Mortars. Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2013, 2, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.C. Hydration and Internal Curing Properties of Plant-Based Natural Fiber-Reinforced Cement Composites. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawab, M.S.; Ali, T.; Qureshi, M.Z.; Zaid, O.; Kahla, N.B.; Sun, Y.; Anwar, N.; Ajwad, A. A Study on Improving the Performance of Cement-Based Mortar with Silica Fume, Metakaolin, and Coconut Fibers. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaud, L.; Gourlay, E. Experimental Study of Parameters Influencing Mechanical Properties of Hemp Concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 28, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baley, C.; Perrot, Y.; Busnel, F.; Guezenoc, H.; Davies, P. Transverse Tensile Behaviour of Unidirectional Plies Reinforced with Flax Fibres. Mater. Lett. 2006, 60, 2984–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, L.; Park, Y.D.; Shah, S.P. A Method for Mix-Design of Fiber-Reinforced Self-Compacting Concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2007, 37, 957–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertelsen, I.M.G.; Lima, A.T.M.; Ottosen, L.M. Possible Applications for Waste Fishing Nets in Construction Material. In Marine Plastics: Innovative Solutions to Tackling Waste; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 211–241. [Google Scholar]

- Spadea, S.; Farina, I.; Carrafiello, A.; Fraternali, F. Recycled Nylon Fibers as Cement Mortar Reinforcement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 80, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Meyer, C. Degradation Mechanisms of Natural Fiber in the Matrix of Cement Composites. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 73, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollo, R.F. Fiber-Reinforced Concrete: An Overview after 30 Years of Development. Cem. Concr. Compos. 1997, 19, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnell, P. Mechanical Behaviour and Properties of Composites; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- de Andrade Silva, F.; Toledo Filho, R.D.; de Almeida Melo Filho, J.; Fairbairn, E.D.M.R. Physical and Mechanical Properties of Durable Sisal Fiber–Cement Composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, K.; Shabbir, F.; Raza, A. Performance Evaluation of Jute Fiber-reinforced Recycled Aggregate Concrete: Strength and Durability Aspects. Struct. Concr. 2023, 24, 6520–6538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Oqla, F.M.; Sapuan, S.M. Natural Fiber Reinforced Polymer Composites in Industrial Applications: Feasibility of Date Palm Fibers for Sustainable Automotive Industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 66, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh, M.; Mousavi, S.S.; Hosseinzadeh, A.; Dehestani, M. An Efficient Machine Learning Approach for Predicting Concrete Chloride Resistance Using a Comprehensive Dataset. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobaka, J. Principal Component Analysis as a Statistical Tool for Concrete Mix Design. Materials 2021, 14, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobaka, J.; Katzer, J. A Principal Component Analysis in Concrete Design. Constr. Optim. Energy Potential Bud. O Zoptymalizowanym Potencjale Energetycznym 2022, 11, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Xue, E.W.; Gu, X.B. Evaluation of Coarse Aggregate Quality Grade of Recycled Concrete Based on the Principal Component Analysis-Cloud Model. Front. Mater. 2023, 10, 1291434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charhate, S.; Subhedar, M.; Adsul, N. Prediction of Concrete Properties Using Multiple Linear Regression and Artificial Neural Network. J. Soft Comput. Civ. Eng. 2018, 2, 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Z.; Xu, Y.; Šavija, B. On the Use of Machine Learning Models for Prediction of Compressive Strength of Concrete: Influence of Dimensionality Reduction on the Model Performance. Materials 2021, 14, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Abbas, Y.M.; Fares, G. Review of High and Ultrahigh Performance Cementitious Composites Incorporating Various Combinations of Fibers and Ultrafines. J. King Saud Univ.-Eng. Sci. 2017, 29, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balea, A.; Fuente, E.; Monte, M.C.; Blanco, Á.; Negro, C. Fiber Reinforced Cement Based Composites. In Fiber Reinforced Composites; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 597–648. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrathilaka, E.R.K.; Baduge, S.K.; Mendis, P.; Thilakarathna, P.S.M. Structural Applications of Synthetic Fibre Reinforced Cementitious Composites: A Review on Material Properties, Fire Behaviour, Durability and Structural Performance. Structures 2021, 34, 550–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Cao, M.; Khan, M.; Yin, H.; Guan, J. Review on Different Testing Methods and Factors Affecting Fracture Properties of Fiber Reinforced Cementitious Composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 273, 121766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Zou, Y.; Wan, X.; Li, W. Mechanical Investigation on Fiber-Doped Cementitious Materials. Polymers 2022, 14, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, C.; Zhang, P.; Wang, J.; Hu, S. Influence of Fibers on the Mechanical Properties and Durability of Ultra-High-Performance Concrete: A Review. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 52, 104370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younes, K.; Abdallah, M.; Hanna, E.G. The Application of Principal Components Analysis for the Comparison of Chemical and Physical Properties among Activated Carbon Models. Mater. Lett. 2022, 325, 132864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouhtady, O.; Obeid, E.; Abu-samha, M.; Younes, K.; Murshid, N. Evaluation of the Adsorption Efficiency of Graphene Oxide Hydrogels in Wastewater Dye Removal: Application of Principal Component Analysis. Gels 2022, 8, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younes, K.; Mouhtady, O.; Chaouk, H.; Obeid, E.; Roufayel, R.; Moghrabi, A.; Murshid, N. The Application of Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for the Optimization of the Conditions of Fabrication of Electrospun Nanofibrous Membrane for Desalination and Ion Removal. Membranes 2021, 11, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazo Hanna, E.; Younes, K.; Amine, S.; Roufayel, R. Exploring Gel-Point Identification in Epoxy Resin Using Rheology and Unsupervised Learning. Gels 2023, 9, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younes, K.; Kharboutly, Y.; Antar, M.; Chaouk, H.; Obeid, E.; Mouhtady, O.; Abu-samha, M.; Halwani, J.; Murshid, N. Application of Unsupervised Learning for the Evaluation of Aerogels’ Efficiency towards Dye Removal—A Principal Component Analysis (PCA) Approach. Gels 2023, 9, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joliffe, I.; Morgan, B. Principal Component Analysis and Exploratory Factor Analysis. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 1992, 1, 69–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaouk, H.; Obeid, E.; Halwani, J.; Abdelbaki, W.; Dib, H.; Mouhtady, O.; Gazo Hanna, E.; Fernandes, C.; Younes, K. Investigating the Physical and Operational Characteristics of Manufacturing Processes for MFI-Type Zeolite Membranes for Ethanol/Water Separation via Principal Component Analysis. Processes 2024, 12, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhabib, W.; Alhawal, J.; AlRashidi, B.; AlAbdulqader, S.; AlSayegh, Z.; Mustafaraj, E. The Impact of Recycled Material Reinforcement on the Performance of Mortars. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2024, 14, 17214–17221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, E.; Younes, K. Uncovering Key Factors in Graphene Aerogel-Based Electrocatalysts for Sustainable Hydrogen Production: An Unsupervised Machine Learning Approach. Gels 2024, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younes, K.; Grasset, L. Carbohydrates as Proxies in Ombrotrophic Peatland: DFRC Molecular Method Coupled with PCA. Chem. Geol. 2022, 606, 120994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample No. | Vf * (%) | Fd * (mm) | Ts * (MPa) | Fl * (mm) | Experimental Flexural Strength, Fs (MPa) | Experimental Compressive Strength, Cs (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.00 | 0.3 | 41 | 10 | 4.40 | 21.04 |

| 2 | 3.00 | 0.3 | 41 | 10 | 3.79 | 19.88 |

| 3 | 1.60 | 0.4 | 53 | 10 | 4.07 | 26.03 |

| 4 | 1.00 | 0.8 | 155 | 10 | 3.19 | 14.31 |

| 5 | 2.00 | 0.8 | 155 | 10 | 4.64 | 25.14 |

| 6 | 3.00 | 0.8 | 155 | 10 | 3.69 | 22.74 |

| 7 | 0.75 | 0.3 | 900 | 15 | 5.09 | 26.62 |

| 8 | 0.10 | 0.31 | 415 | 15 | 4.54 | 24.01 |

| 9 | 0.20 | 0.31 | 415 | 15 | 4.52 | 24.72 |

| 10 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 415 | 15 | 4.48 | 27.37 |

| Sample No. | Experimental Flexural Strength, Fs (MPa) | Predicted Fs (MPa) | Error (%)—Predicted vs. Experimental | Experimental Compressive Strength, Cs (MPa) | Predicted Cs (MPa) | Error (%)—Predicted vs. Experimental |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.40 | 4.71 | 7.07% | 21.04 | 24.33 | 15.62% |

| 2 | 3.79 | 4.72 | 24.61% | 19.88 | 24.34 | 22.44% |

| 3 | 4.07 | 4.64 | 14.01% | 26.03 | 22.77 | 12.51% |

| 4 | 3.19 | 4.23 | 32.85% | 14.31 | 16.07 | 12.28% |

| 5 | 4.64 | 4.24 | 8.72% | 25.14 | 16.07 | 36.06% |

| 6 | 3.69 | 4.24 | 14.93% | 22.74 | 16.08 | 29.27% |

| 7 | 5.09 | 2.99 | 41.37% | 26.62 | 16.59 | 37.67% |

| 8 | 4.54 | 3.95 | 12.95% | 24.01 | 20.80 | 13.37% |

| 9 | 4.52 | 3.95 | 12.68% | 24.72 | 20.80 | 15.83% |

| 10 | 4.48 | 3.95 | 11.88% | 27.37 | 20.80 | 23.99% |

| Sample No. | Experimental Flexural Strength, Fs (MPa) | Predicted Fs (MPa) | Error (%) Predicted vs. Experimental | Experimental Compressive Strength, Cs (MPa) | Predicted Cs (MPa) | Error (%)—Predicted vs. Experimental |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.40 | 4.20 | 4.58% | 21.04 | 17.83 | 15.28% |

| 2 | 3.79 | 4.20 | 10.91% | 19.88 | 17.81 | 10.39% |

| 3 | 4.07 | 4.20 | 3.25% | 26.03 | 17.84 | 31.48% |

| 4 | 3.19 | 4.20 | 31.78% | 14.31 | 17.84 | 24.72% |

| 5 | 4.64 | 4.20 | 9.57% | 25.14 | 17.83 | 29.08% |

| 6 | 3.69 | 4.20 | 13.70% | 22.74 | 17.81 | 21.66% |

| 7 | 5.09 | 5.10 | 0.10% | 26.62 | 22.25 | 16.41% |

| 8 | 4.54 | 5.10 | 12.43% | 24.01 | 22.26 | 7.31% |

| 9 | 4.52 | 5.10 | 12.76% | 24.72 | 22.26 | 9.95% |

| 10 | 4.48 | 5.10 | 13.79% | 27.37 | 22.26 | 18.69% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mustafaraj, E.; Luga, E.; El Sawda, C.; Ziade, E.; Younes, K. Principal Component and Multiple Linear Regression Analysis for Predicting Strength in Fiber-Reinforced Cement Mortars. Constr. Mater. 2026, 6, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/constrmater6010011

Mustafaraj E, Luga E, El Sawda C, Ziade E, Younes K. Principal Component and Multiple Linear Regression Analysis for Predicting Strength in Fiber-Reinforced Cement Mortars. Construction Materials. 2026; 6(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/constrmater6010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleMustafaraj, Enea, Erion Luga, Christina El Sawda, Elio Ziade, and Khaled Younes. 2026. "Principal Component and Multiple Linear Regression Analysis for Predicting Strength in Fiber-Reinforced Cement Mortars" Construction Materials 6, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/constrmater6010011

APA StyleMustafaraj, E., Luga, E., El Sawda, C., Ziade, E., & Younes, K. (2026). Principal Component and Multiple Linear Regression Analysis for Predicting Strength in Fiber-Reinforced Cement Mortars. Construction Materials, 6(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/constrmater6010011