Theoretical Solutions of Wave-Induced Seabed Response Under Fully Drained and Undrained Conditions for Verification of a Numerical Analysis Code

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Study Background

1.2. Review of the Existing Theoretical Solutions for Wave-Induced Seabed Behavior

- Prévost et al. [8] and Mallaid and Dalrymple [9] assumed that the seabed is an elastic solid and there is neither pore water flow nor compressibility of pore water. Prévost et al. [8] considered that there is no volumetric change in the soil skeleton, and the change in the mean total stress corresponds to the change in excess pore water pressure. The solution of Mallaid and Dalrymple [9] solves the static equilibrium equations by neglecting excess pore water pressure, i.e., the one-phase elastic deformation problem of the soil skeleton.

- Hsu and Jeng [14] derived a solution for a seabed with a finite vertical length under plane stress condition.

- Mei and Foda [15] also addressed the same problem as that of Yamamoto’s solution [1] using the boundary layer theory, dividing a seabed into two layers. The “outer layer,” located deeper, is assumed to be impermeable, whereas the “boundary layer,” near the surface, is considered to allow pore water flow inside the soil skeleton.

- Jeng and Rahman [16] derived a theoretical solution based on - formulation, i.e., considering the inertia terms of the soil skeleton with the relative acceleration of pore water flow neglected. Then, Jeng and Cha [17] and Ulker et al. [18] derived theoretical solutions considering the inertia terms of both the soil skeleton and relative pore water flow, i.e., -- formulation. Ulker et al. [18] compared the analytical results to evaluate the applicability of each solution concerning seabed soil permeability.

| Soil Skeleton Deformation | Compressibility of Pore Water | Relative Pore Water Flow | Note a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Putnam [2] | × | × | ○ | Infinite thickness |

| Reid and Kajiura [3] | Infinite thickness; effect of water pressure damping at the seabed surface considered | |||

| Sleath [4] | Infinite thickness; anisotropic permeability of seabed considered | |||

| Liu [5] | Infinite thickness; rotational field considered | |||

| Nakamura et al. [6] | × | ○ | ○ | Infinite thickness |

| Moshagen and Tørum [7] | Finite thickness | |||

| Prévost et al. [8] | ○ | × | × | No compressibility of the soil skeleton Excess pore water pressure was evaluated |

| Mallaid and Dalrymple [9] | One-phase Biot’s consolidation equation was solved. Excess pore water pressure was not evaluated | |||

| Yamamoto [1] | ○ | ○ | ○ | Finite thickness; plane strain |

| Yamamoto et al. [11] | Infinite thickness; plane strain | |||

| Madsen [12] | Infinite thickness; plane strain | |||

| Okusa [13] | Infinite thickness; plane strain | |||

| Hsu and Jeng [14] | Finite thickness; plane stress | |||

| Mei and Foda [15] | Infinite thickness; plane strain; boundary layer theory | |||

| Jeng and Rahman [16] | Finite thickness; plane strain; - | |||

| Jeng and Cha [17] | Finite thickness; plane strain; -; --p | |||

| Ulker et al. [18] | Finite thickness; plane strain; -p; --p |

1.3. Structure of This Paper

2. Limitations of Yamamoto’s Theoretical Solution

- Linear isotropic elasticity of the seabed.

- Material homogeneity.

- Infinitesimal (strain) deformation.

- Two-dimensional plane strain condition.

- Quasi-static formulation, which neglects the inertia terms of both the soil skeleton and pore water.

- The state of equilibrium of forces considered as a reference, allowing neglect of the gravitational force.

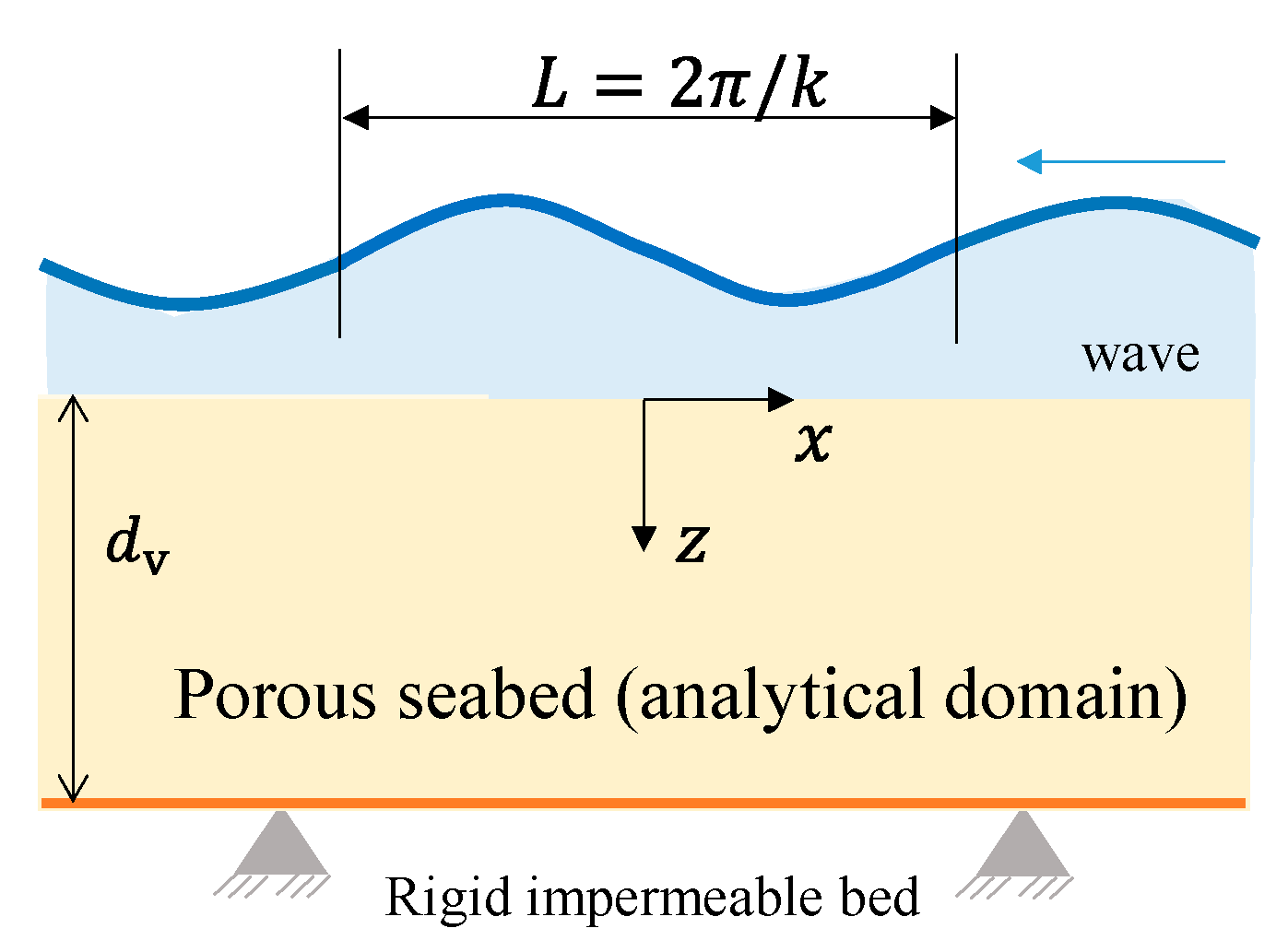

- Progressive sinusoidal wave applied as the total vertical stress and pore water pressure on the seabed surface.

- Infinite horizontal length such that the seabed behavior can be assumed to be periodic in the horizontal direction.

- Finite vertical length (thickness) with its uniformity in the horizontal direction.

- Compressibility of pore water is dependent on pore water pressure.

- Incompressibility of soil particles.

- Fixed displacement at the bottom.

- Steady solution, i.e., a particular solution.

- Pore water flow subject to Darcy’s law, with a finite permeability coefficient, i.e., under a partially drained condition

2.1. Non-Dimensionalization of the Problem

2.2. Inapplicability of Yamamoto’s Solution near Fully Drained and Undrained Conditions

- (a)

- Fully drained condition

- (b)

- Fully undrained condition

3. Theoretical Solutions for the Wave-Induced Response of a Seabed Under Fully Drained and Undrained Conditions

3.1. Derivation of the Solutions

- (a)

- Solution for the seabed behavior under fully drained condition

- (b)

- Solution for the seabed behavior under fully undrained condition

3.2. Feasibility of the Solutions

3.3. Characteristics of the Solutions

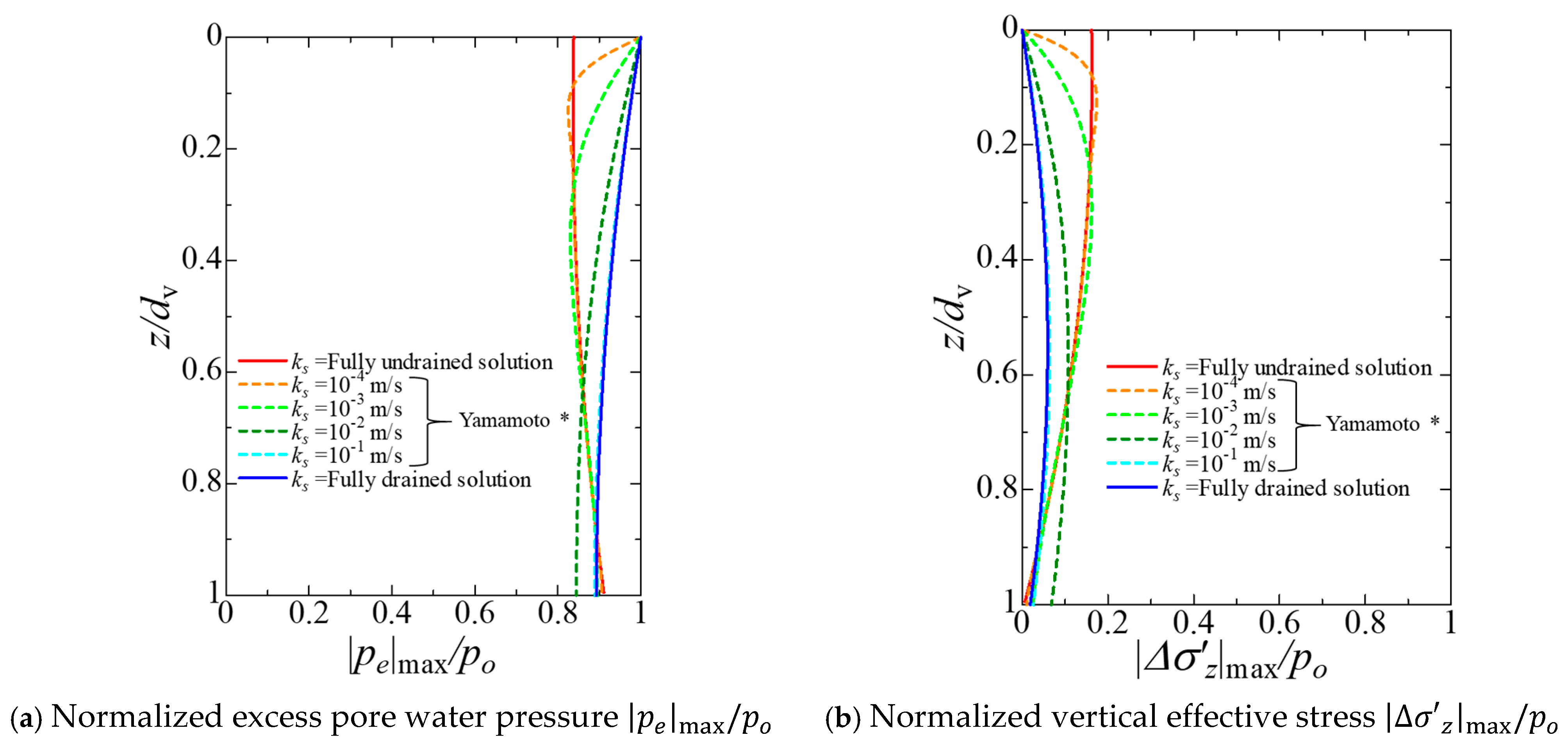

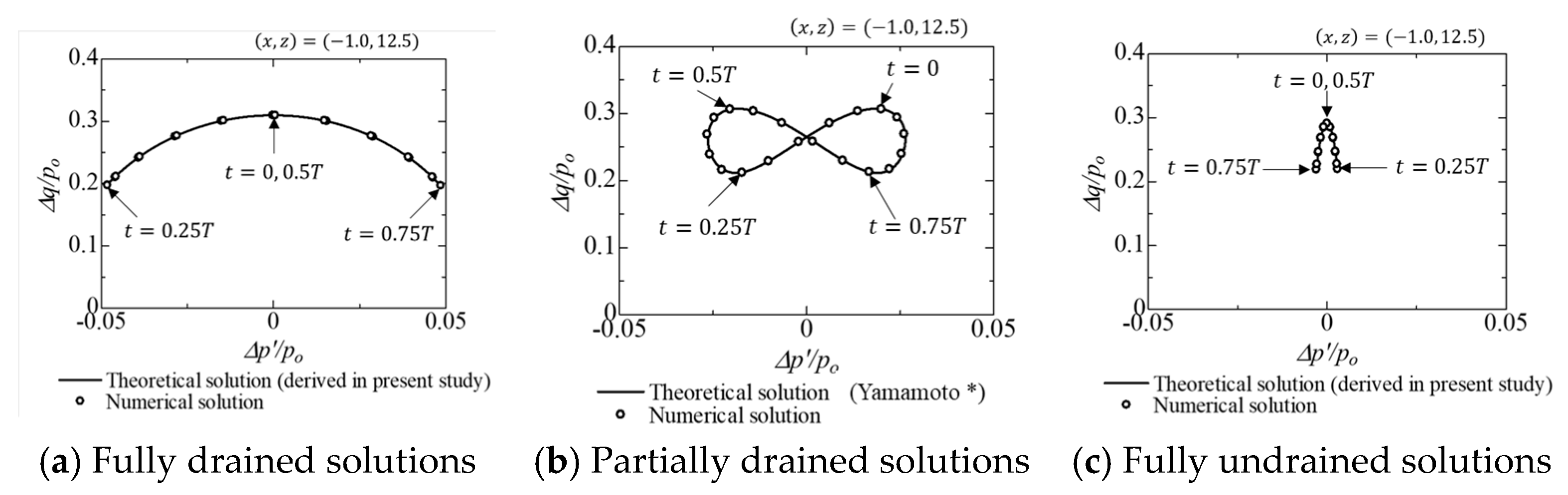

- For the fully drained solution, the excess pore water pressure , which was determined by Laplace’s equation independently of the static equilibrium equations (Equation (6)), showed the largest values at almost any location. This resulted in the smallest incremental vertical effective stress virtually throughout the depth.

- For the fully undrained solution, it was observed at the seabed surface () that was not zero and did not correspond to wave pressure amplitude . This is due to the boundary condition given by Equation (27-1), which specifies the incremental total stress corresponding to wave loading, i.e., , instead of and . In this case, the distribution of , which showed the smallest values at almost any location, was determined to prohibit volume change due to pore water flow.

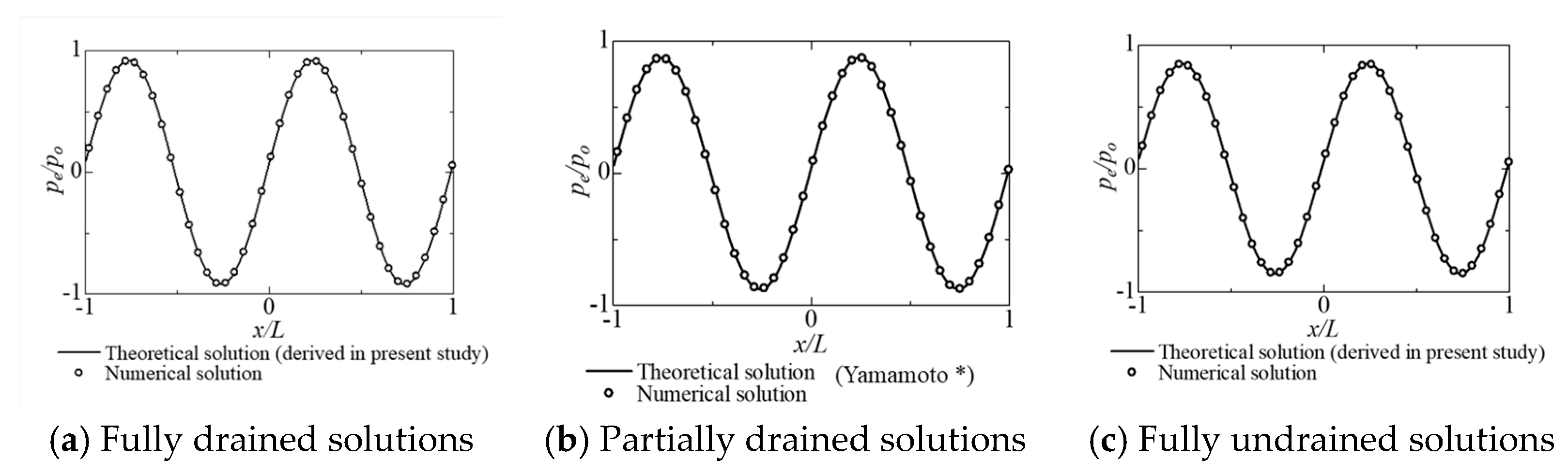

4. Verification of a Numerical Analysis Code by the Theoretical Solutions

5. Conclusions

- The dimensionless form of Yamamoto’s solution [1] for a two-dimensional response of an elastic seabed with finite thickness was derived with the newly introduced dimensionless parameter , representing the ratio of wave pressure amplitude to total stiffness , which is the sum of soil stiffness and bulk modulus of the pore fluid.

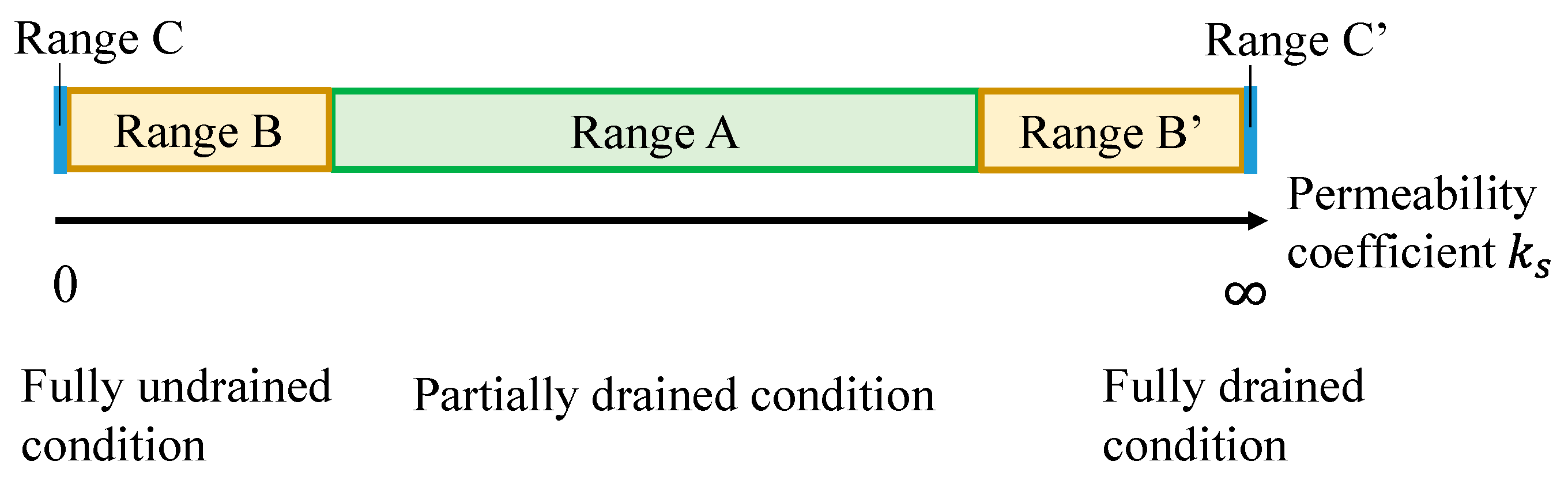

- The change in the condition number, calculated from the matrix to determine the coefficients of Yamamoto’s solution, was analyzed regarding the permeability coefficient . We found that Yamamoto’s solution was no longer valid if the permeability coefficient was sufficiently large ( m/s) or small ( m/s) under the analytical conditions listed in Table 4, as the matrix turned out to be singular in such cases.

- Theoretical solutions for the wave-induced responses of the seabed under the fully drained and undrained conditions were newly derived by considering the limits of the continuity equation with the permeability coefficient reaching infinity and zero, respectively.

- A comparison of the forms of the solutions revealed that the fully drained solution is feasible because the six function vectors remain, and thus the solution can express the six independent boundary conditions satisfactorily. Furthermore, the form of the fully undrained solution comprising four independent function vectors is suitable for expressing the four boundary conditions that should be met under the fully undrained condition.

- Characteristics of the fully drained and undrained seabed behaviors were observed under certain analytical conditions. Under the fully drained condition, excess pore water pressure was determined by Laplace’s equation and the largest almost throughout the depth. Under the fully undrained condition, disagreement between excess pore water pressure and wave pressure amplitude at the seabed surface was observed owing to the vertical total stress given at the seabed surface.

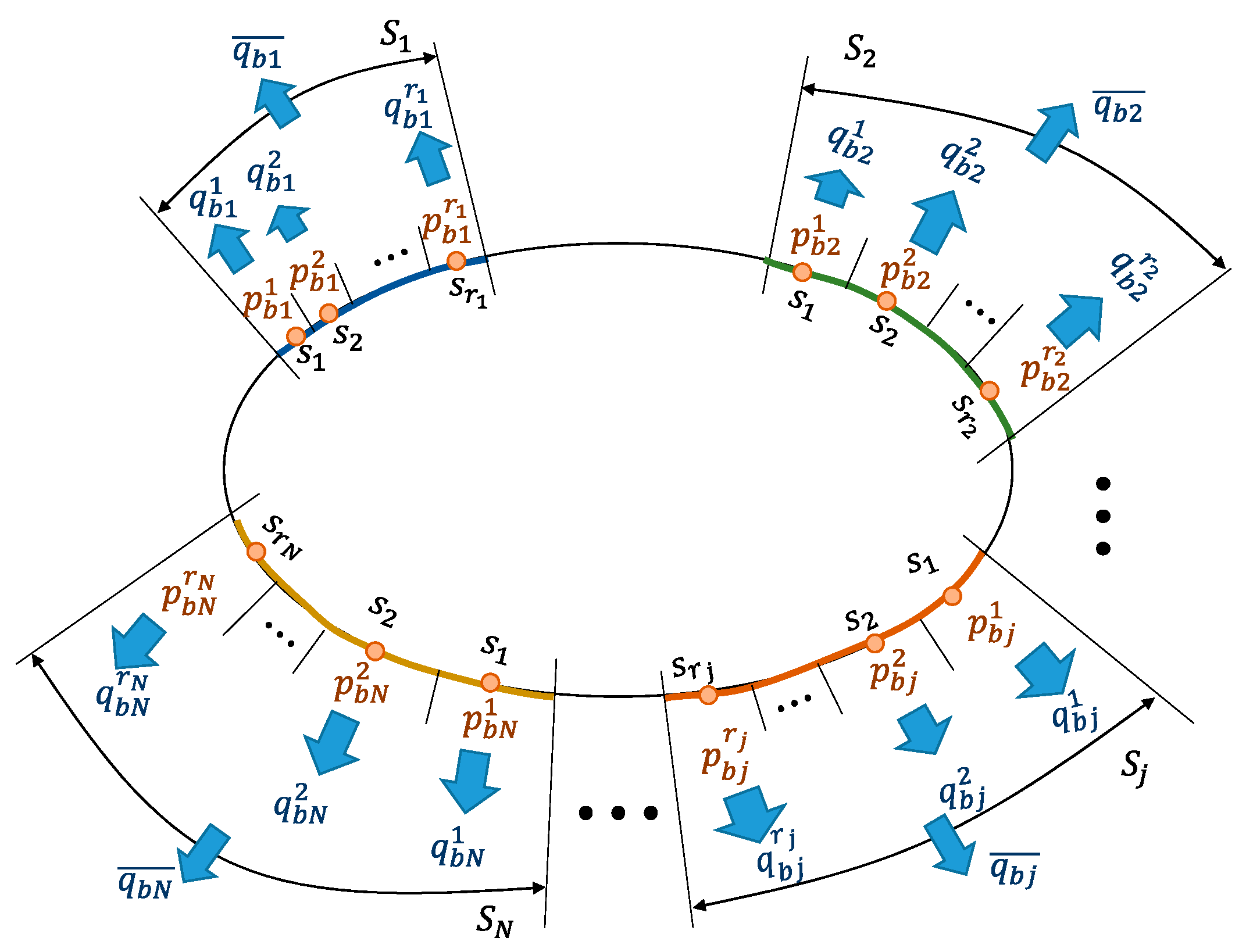

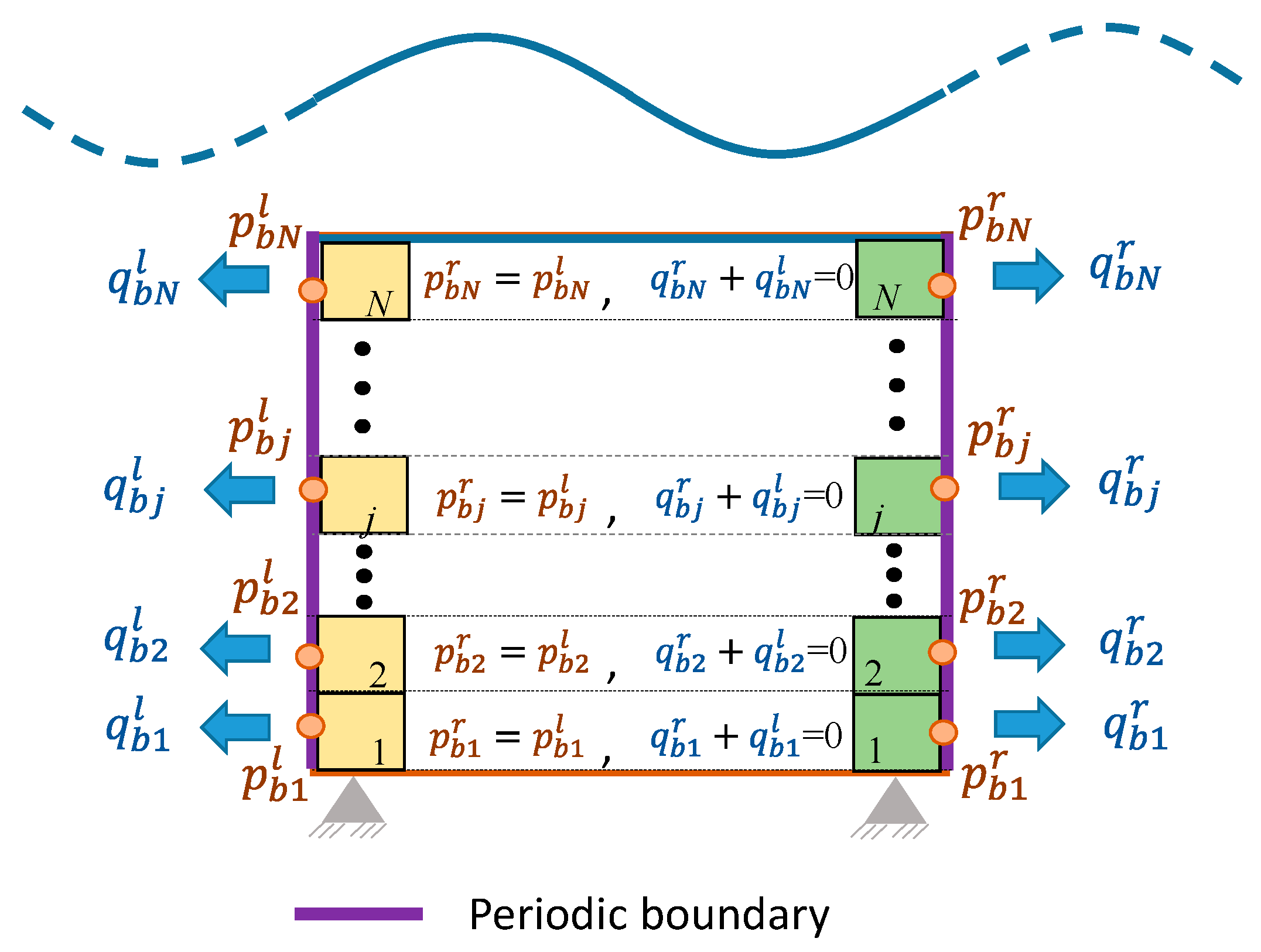

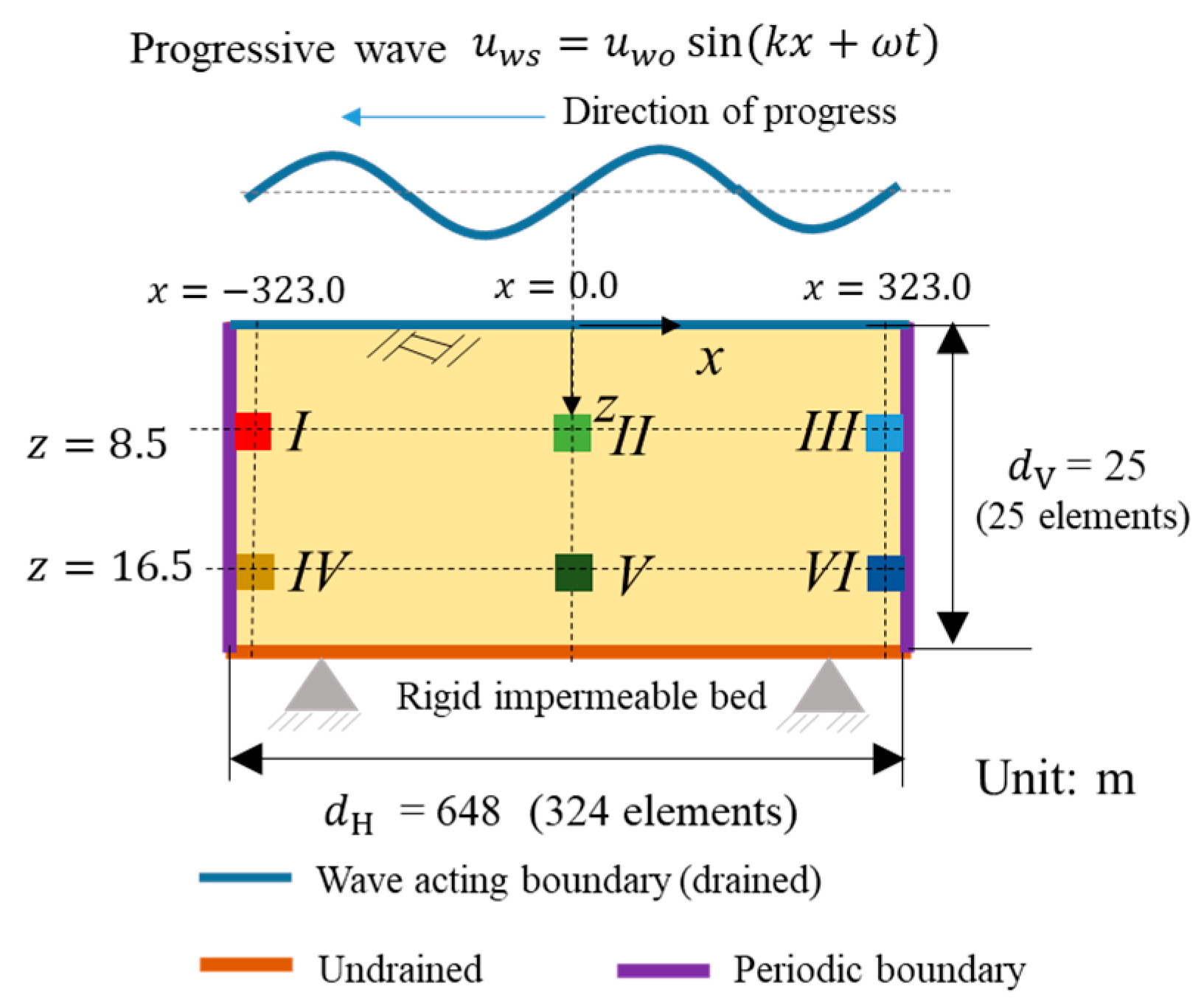

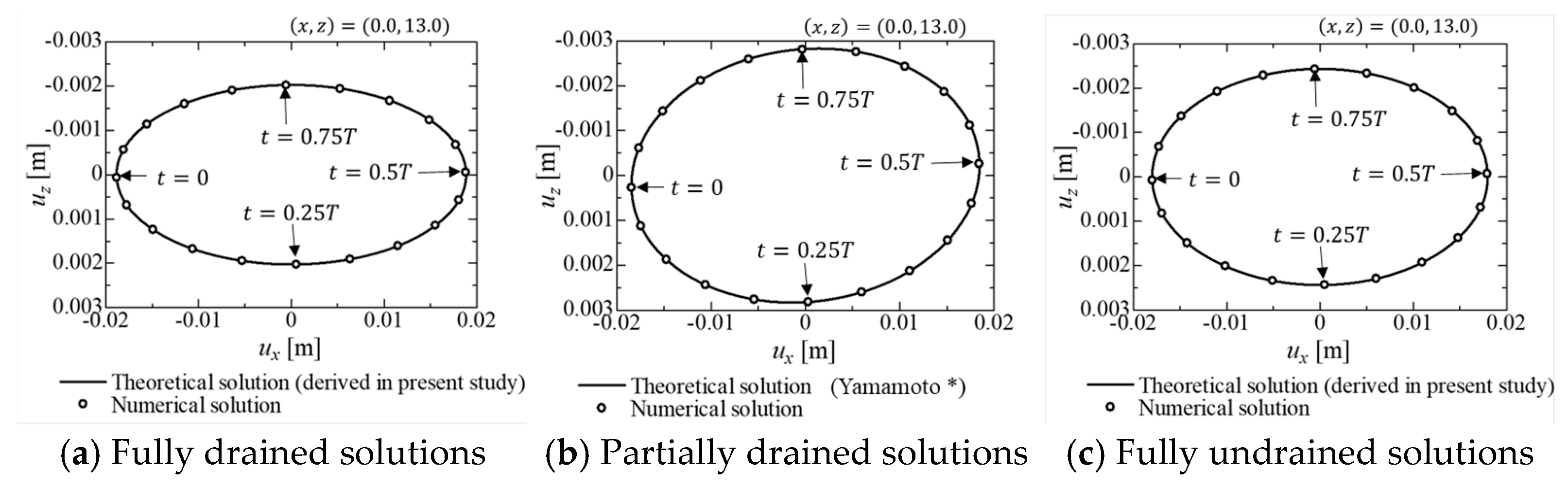

- The newly derived theoretical solutions and Yamamoto’s solution were used for verification of the finite element numerical analysis code. To this end, horizontal periodicity of soil displacement, pore water pressure, and flow was considered in the numerical analysis. As for the soil displacement field, the method of Lagrange multiplier was utilized. Regarding the pore water pressure field, -- formulation, in which boundary water pressures are treated as unknown variables, was employed to consider periodic boundary conditions of pore water pressure and flow, solved with the static equilibrium and continuity equations.

- The numerical analysis code did not need approximation to the governing equation, especially the continuity equation, as made in the derivation of the new theoretical solutions. This is because independence of functions for displacements and the physical model of pore water flow in numerical analysis allow arbitrary expression of bases of the theoretical solutions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Governing Equations of Yamamoto (1977) [1]: Solution and Interpretations of the Continuity Equation

Appendix B. General Concept of -- Formulation Based on the Finite Volume Method (FVM) with the Physical Model

References

- Yamamoto, T. Wave induced instability in seabeds. In Proceedings of the ASCE Special Conference: Coastal Sediments, Charleston, SC, USA, 16–18 November 1977; pp. 898–913. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, J.A. Loss of wave energy due to percolation in a permeable sea bottom. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 1949, 30, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, R.O.; Kajiura, K. On the damping of gravity waves over a permeable sea bed. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 1957, 38, 662–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleath, J.F. Wave-induced pressures in beds of sand. J. Hydraul. Div. 1970, 96, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.L. Damping of water waves over porous bed. J. Hydraul. Div. 1973, 99, 2263–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, H.; Onishi, R.; Minamide, H. On the seepage in the seabed due to waves. In Proceedings of the 20th Coastal Engineering Conference, Nagoya, Japan, 9–14 November 1973; pp. 421–428. [Google Scholar]

- Moshagen, H.; Tørum, A. Wave induced pressures in permeable seabeds. J. Waterw. Harb. Coast. Eng. Div. 1975, 101, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prévost, J.H.; Eide, O.; Andersen, K.H. Discussions of “wave induced pressures in permeable seabeds”. J. Waterw. Harb. Coast. Eng. Div. 1975, 101, 464–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallard, W.W.; Dalrymple, R.A. Water waves propagating over a deformable bottom. In Proceedings of the Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, TX, USA, 1–4 May 1977. OTC-2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biot, M.A. General theory of three-dimensional consolidation. J. Appl. Phys. 1941, 12, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Koning, H.L.; Sellmeijer, H.; Van Hijum, E. On the response of a poro-elastic bed to water waves. J. Fluid Mech. 1978, 87, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, O.S. Wave induced pore pressure and effective stresses in porous bed. Géotechnique 1978, 28, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okusa, S. Wave-induced stresses in unsaturated submarine sediments. Géotechnique 1985, 35, 517–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.R.C.; Jeng, D.S. Wave-induced soil response in an unsaturated anisotropic seabed of finite thickness. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 1994, 18, 785–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, C.C.; Foda, M.A. Wave-induced responses in a fluid-filled poro-elastic solid with a free surface—A boundary layer theory. Geophys. J. Int. 1981, 66, 597–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeng, D.S.; Rahman, M.S. Effective stresses in a porous seabed of finite thickness: Inertia effects. Can. Geotech. J. 2000, 37, 1383–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeng, D.-S.; Cha, D.H. Effects of dynamic soil behavior and wave non-linearity on the wave-induced pore pressure and effective stresses in porous seabed. Ocean. Eng. 2003, 30, 2065–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulker, M.B.C.; Rahman, M.S.; Jeng, D.S. Wave-induced response of seabed: Various formulations and their applicability. Appl. Ocean. Res. 2009, 31, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Liu, P.L.F. Transient wave-induced pore-water-pressure and soil responses in a shallow unsaturated poroelastic seabed. J. Fluid Mech. 2022, 938, A36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strang, G. Linear Algebra and Its Applications, 4th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zienkiewicz, O.C.; Chang, C.T.; Bettess, P. Drained, undrained, consolidating and dynamic behaviour assumptions in soils. Géotechnique 1980, 30, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Wang, Y.; Liu, P.L.F. A guide for selecting periodic water wave theories-Le Méhauté (1976)’s graph revisited. Coast. Eng. 2024, 188, 104432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyoda, T.; Noda, T. Numerical simulation based heuristic investigation of inertia-induced phenomena and theoretical solution based verification by the damped wave equation for the dynamic deformation of saturated soil based on the u–w–p governing equation. Soils Found. 2021, 61, 352–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaoka, A.; Nakano, M.; Noda, T. Soil-water coupled behavior of saturated clay near/at critical state. Soils Found. 1994, 34, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, T.; Noda, T.; Kodaka, T. Effects of air coupling on triaxial shearing behavior of unsaturated silty specimens under constant confining pressure and various drained and exhausted conditions. Soils Found. 2015, 55, 1372–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, T.; Asaoka, A.; Nakano, M. Soil-water coupled finite deformation analysis based on a rate-type equation of motion incorporating the SYS Cam-clay model. Soils Found. 2008, 48, 771–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, J.T. Undrained stress distribution by numerical methods. J. Soil Mech. Found. Div. 1968, 94, 1333–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akai, K.; Tamura, T. Numerical analysis of multidimensional consolidation accompnaied with elasto-plastic constitutive equation. Proc. Jpn. Soc. Civ. Eng. 1978, 269, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaoka, A.; Noda, T.; Kaneda, K. Displacement/traction boundary conditions represented by constraint conditions on velocity field of soil. Soils Found. 1998, 38, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verruijt, A. Elastic storage of aquifers. In Flow Through Porous Media; De Wiest, R.J.M., Ed.; Academic Press Publishers: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1969; Volume 1, pp. 331–376. [Google Scholar]

| Yamamoto’s Solution [1] | Newly Derived Solutions | Numerical Analysis Codes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Range A | Applicable | Inapplicable | Verifiable by Yamamoto’s solution |

| Ranges B&B′ | Inapplicable | Inapplicable | Unverifiable |

| Ranges C&C′ | Inapplicable | Applicable | Verifiable by newly derived solutions |

| Dimensionless Parameter | Definition | Physical Meanings |

|---|---|---|

| a | Consolidation parameter governing the drainage condition of the seabed | |

| a | Ratio of compressibility of pore fluid to total stiffness, i.e., combination of soil stiffness and bulk modulus of pore fluid | |

| a | Ratio of bulk modulus of soil skeleton to total stiffness | |

| a | Ratio of shear modulus to total stiffness | |

| a | Ratio of thickness of the seabed to wavelength | |

| b | Ratio of wave pressure amplitude to total stiffness |

| Soil Properties | |

| Porosity | |

| Poisson’s ratio | 0.333 |

| Shear modulus (kN/m2) | 10,000 |

| Bulk modulus of pore fluid (kN/m2) a | |

| Degree of saturation | 1.0 |

| Unit weight of water (kN/m3) | 9.81 |

| Wave Conditions | |

| Height H (m) | 11.6 |

| Amplitude (kN/m2) | 57.0 |

| Period T (s) b | |

| Angular frequency () (rad/s) b | |

| Length L (m) b | 324.0 |

| Wave number () (rad/m) | 0.019 |

| Velocity C (=L/T) (m/s) | |

| Dimensionless Parameters | |

| c | - |

| 0.484 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iijima, T.; Toyoda, T.; Noda, T. Theoretical Solutions of Wave-Induced Seabed Response Under Fully Drained and Undrained Conditions for Verification of a Numerical Analysis Code. Geotechnics 2025, 5, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics5040081

Iijima T, Toyoda T, Noda T. Theoretical Solutions of Wave-Induced Seabed Response Under Fully Drained and Undrained Conditions for Verification of a Numerical Analysis Code. Geotechnics. 2025; 5(4):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics5040081

Chicago/Turabian StyleIijima, Takumi, Tomohiro Toyoda, and Toshihiro Noda. 2025. "Theoretical Solutions of Wave-Induced Seabed Response Under Fully Drained and Undrained Conditions for Verification of a Numerical Analysis Code" Geotechnics 5, no. 4: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics5040081

APA StyleIijima, T., Toyoda, T., & Noda, T. (2025). Theoretical Solutions of Wave-Induced Seabed Response Under Fully Drained and Undrained Conditions for Verification of a Numerical Analysis Code. Geotechnics, 5(4), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics5040081