An Integrated QGIS-Based Evacuation Route Optimization Approach for Disaster Preparedness Against Urban Flood in Japan

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

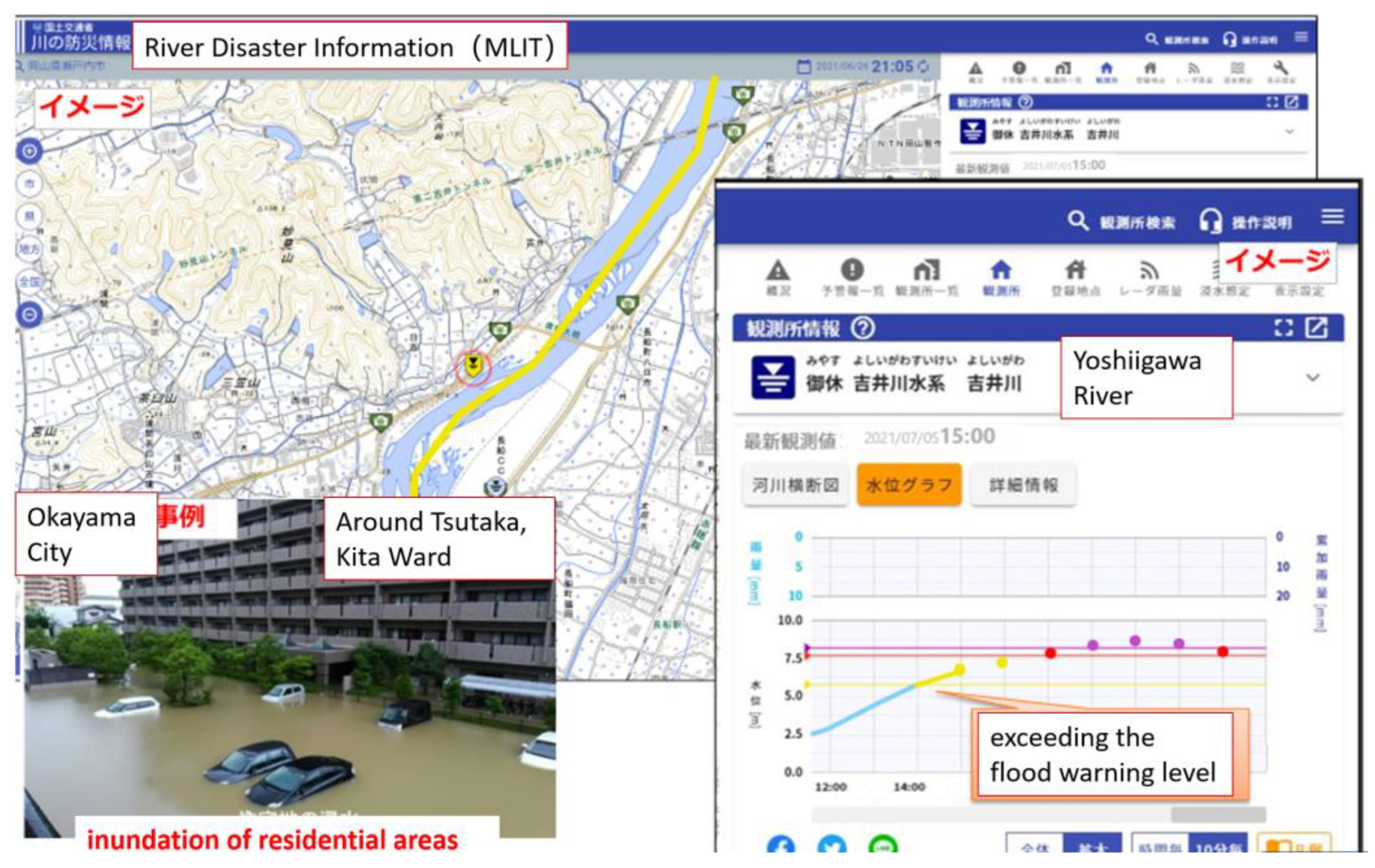

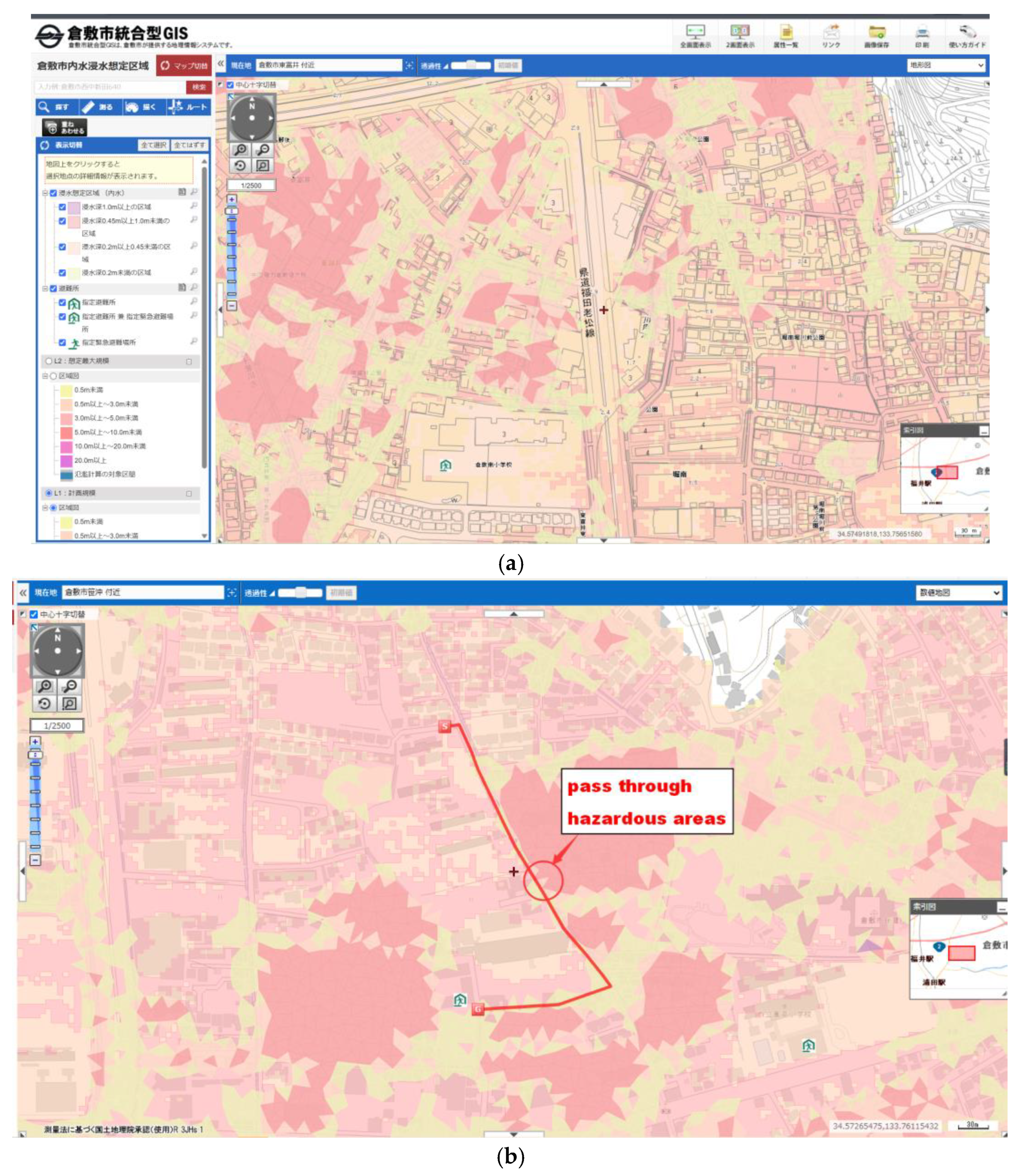

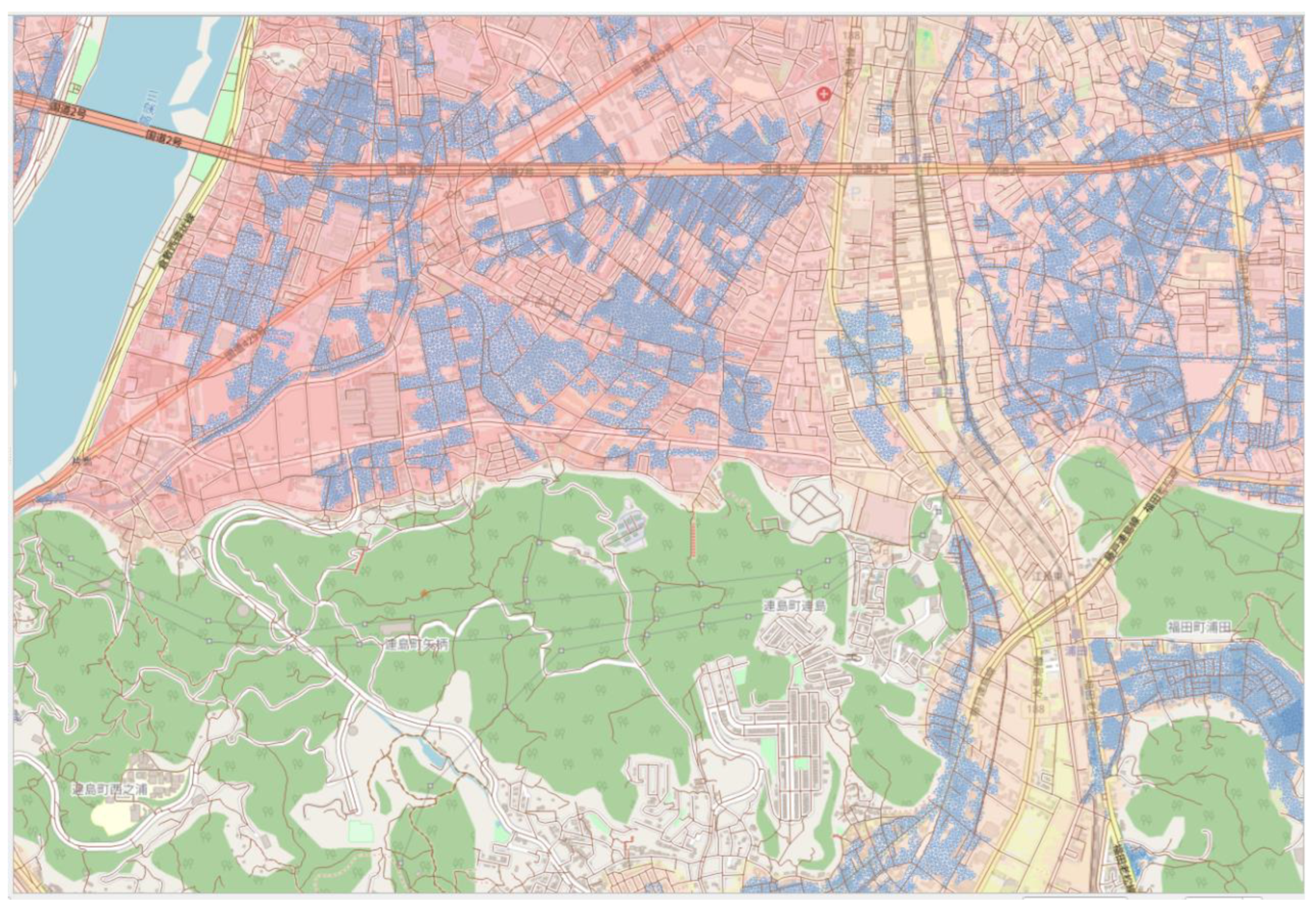

- As shown in Figure 3, the disaster prevention GIS map provided by Okayama City for the general public did not avoid dangerous areas where waterlogging may have occurred.

1.2. Research Status

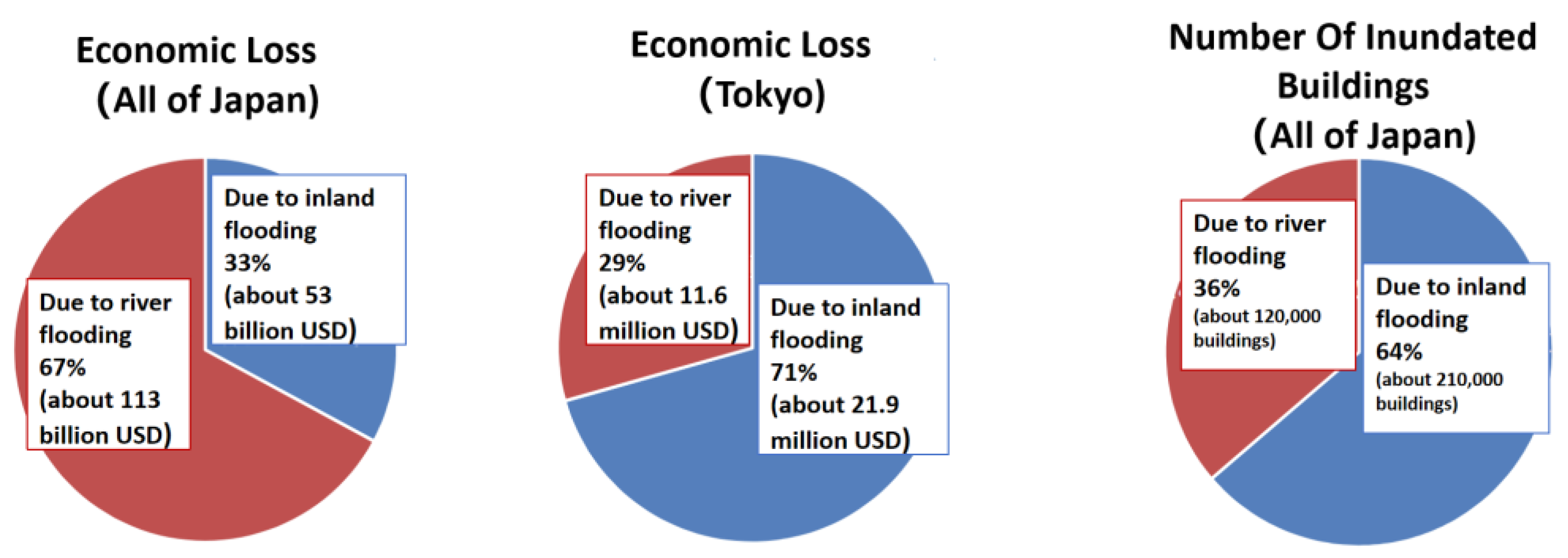

- Scope Limitation: While river flooding is well-studied, models specifically addressing urban inland flooding remain insufficient. Applying river flood models directly to inland scenarios often leads to prediction inaccuracies due to differing flood mechanisms.

- Tool Accessibility: Most existing commercial software is expensive and closed-source, making it difficult for local communities to adopt or customize.

1.3. Objectives and Innovation

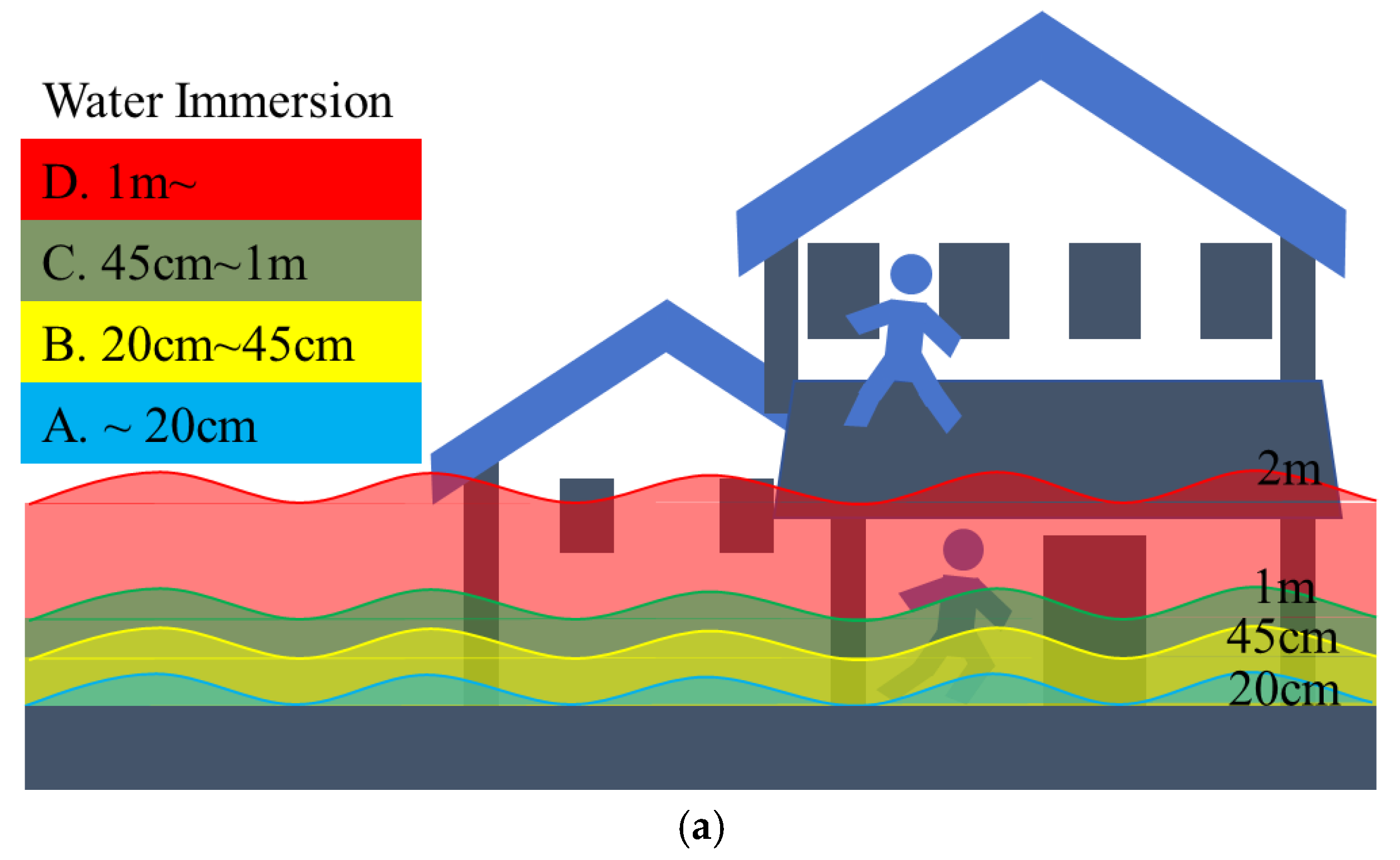

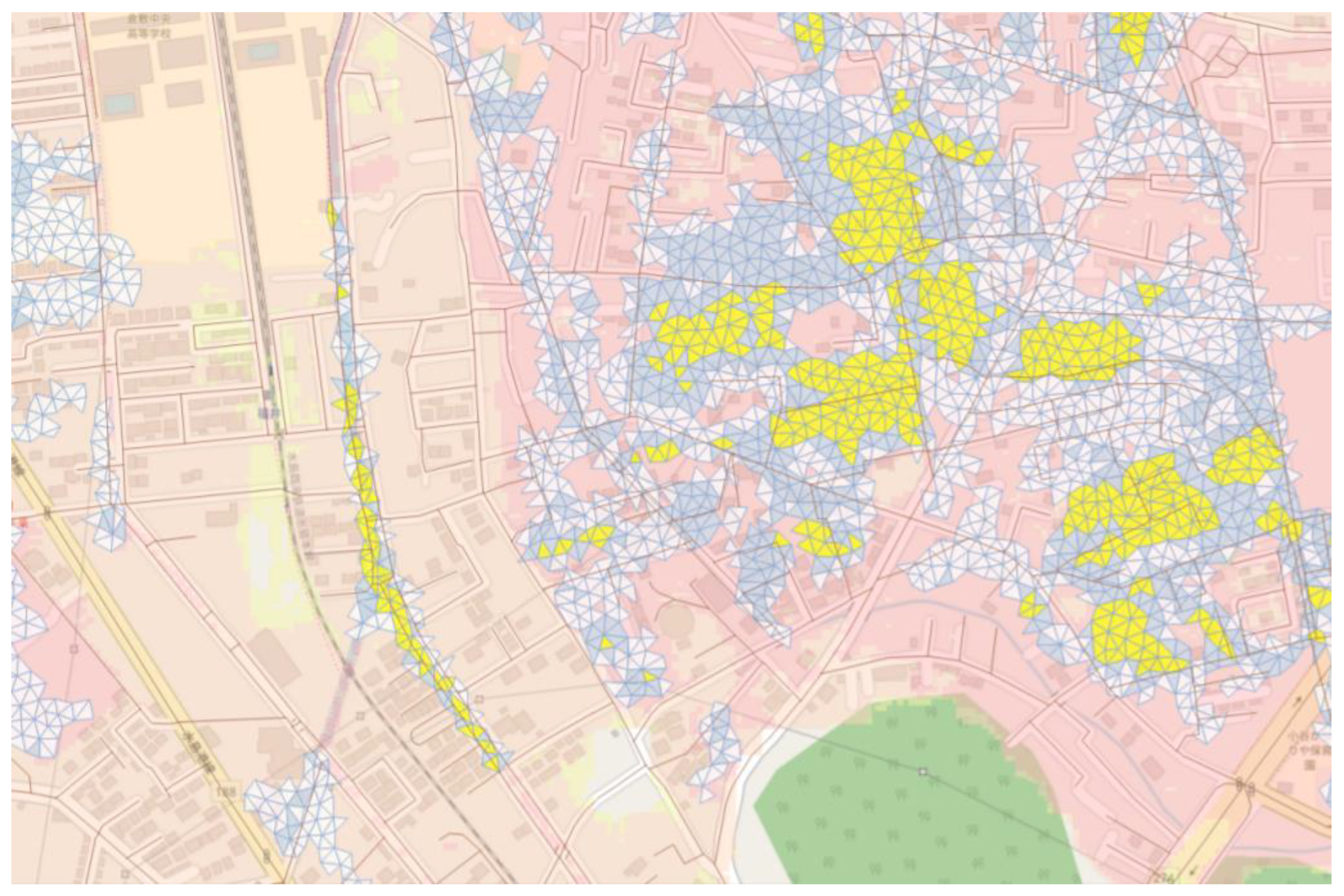

- Establishment of a Safety-Threshold-Based Network: The proposed method integrates inland flooding depth data (as illustrated in Figure 4 and Figure 5 [8]) with road networks. Figure 4 defines the danger levels based on water depth, indicating that a depth of 0.5 m (Danger-level B) is sufficient to compromise the stability of an adult. Based on this physical limit, we set a 0.5 m safety threshold to construct a “Safe Road Network” topology that automatically filters out hazardous road segments.

- Simultaneous Multi-Destination Optimization: Unlike traditional methods, our workflow enables the simultaneous generation of optimal evacuation routes for multiple residential origins to multiple shelters, significantly improving planning efficiency.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Software Framework

2.2.1. Network Analysis

- Distance-based analysis (used in this study)

- 2.

- Time-based analysis (future work)

2.2.2. Definition of the 0.5 m Safety Threshold

2.3. Data Collection (Making Plan of Evacuation Route)

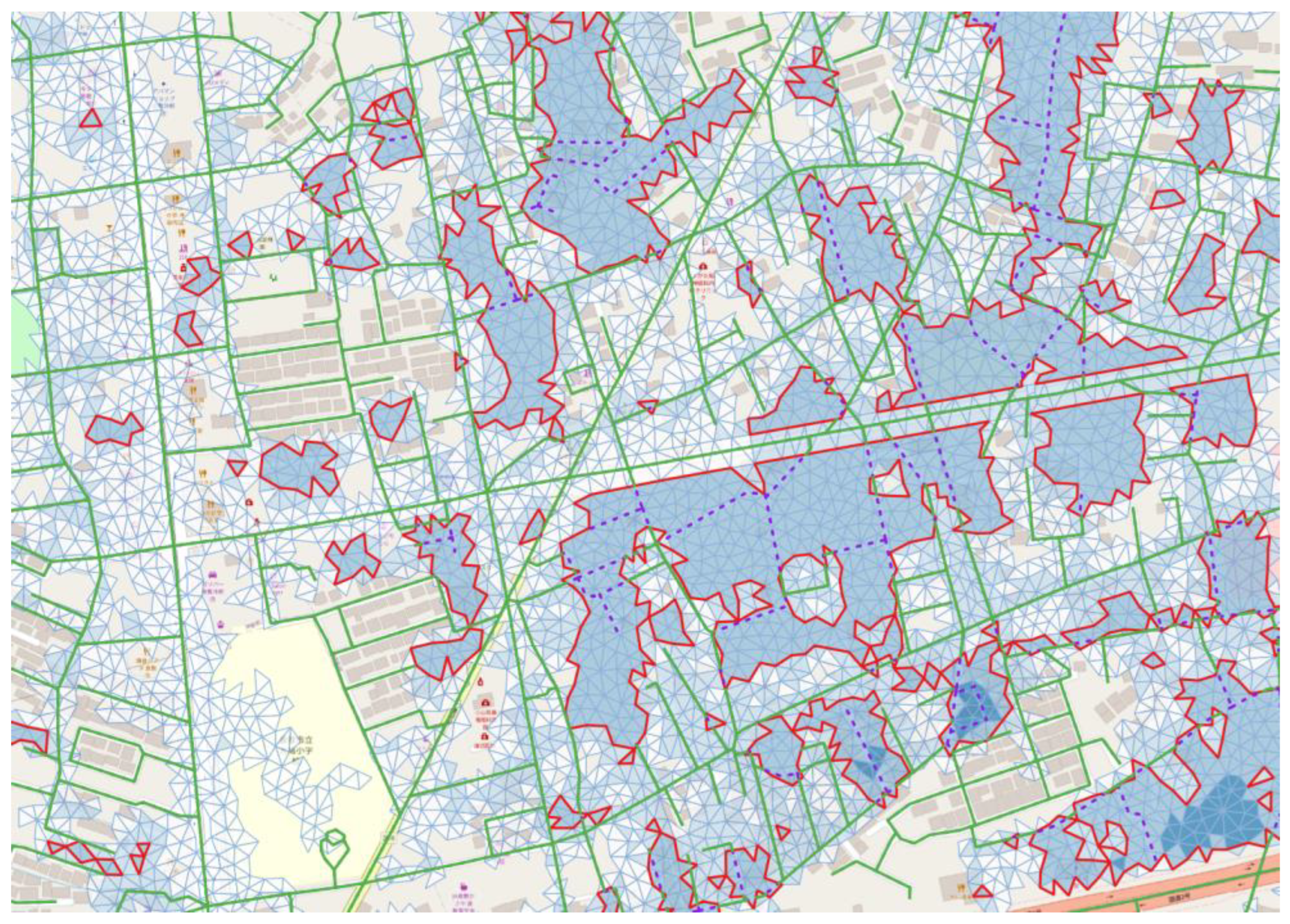

- Road Network Data: The road centerline vector data (Figure 9) were acquired from the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan (GSI). To ensure topological connectivity for network analysis, the raw tile-based data were merged and geometrically corrected to eliminate gaps between road segments.

- Inland Inundation Depth Data: Raster data representing predicted inundation depths under heavy rainfall scenarios were obtained from Kurashiki City’s open data portal. These data provide the basis for risk classification.

- Evacuation Shelter Locations: Point data representing designated emergency shelters were sourced from the official disaster prevention database of Japan.

2.4. Method (Making Plan of Evacuation Route)

2.4.1. Implementation Environment

2.4.2. Construction of Safety-Threshold-Based Road Network

2.4.3. Evacuation Route Making

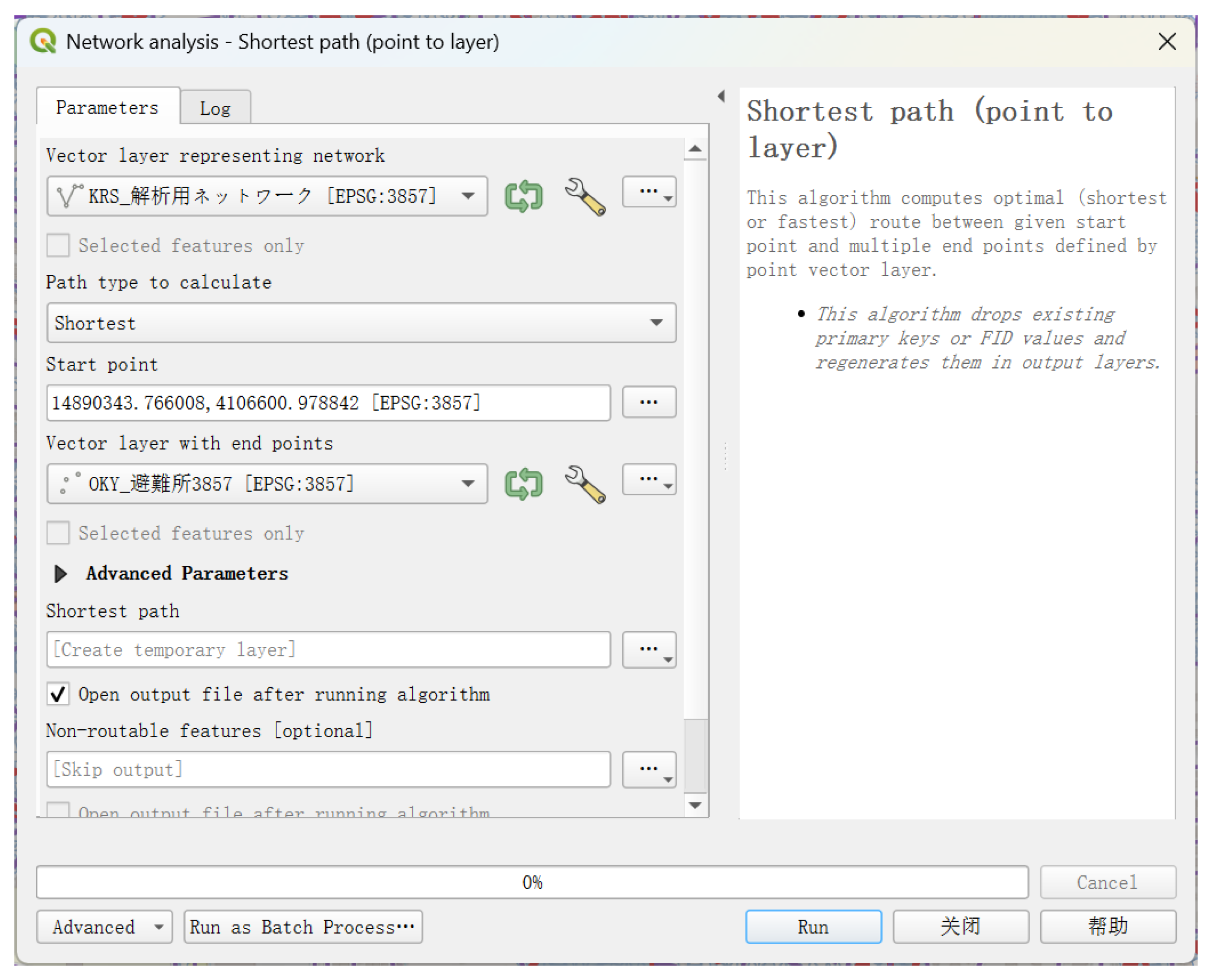

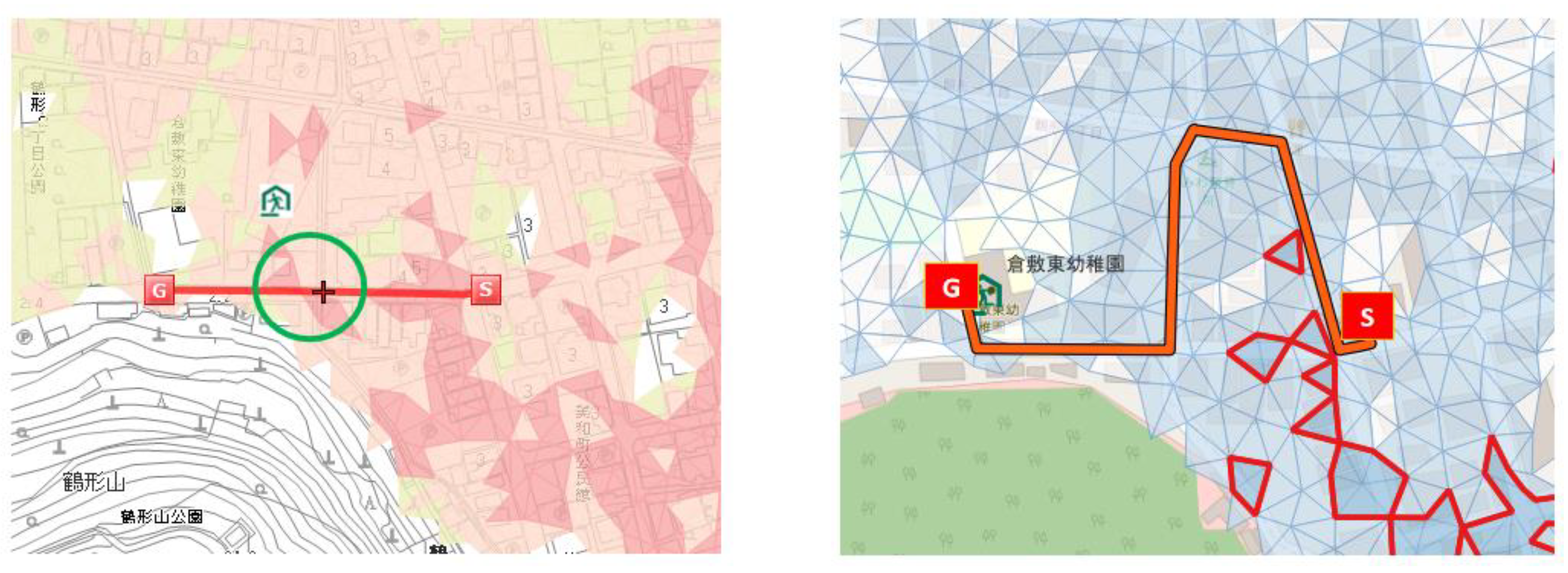

- Figure 12 is the result of the point-to-point analysis. It is possible to perform a route analysis from a specific evacuation source (residential locations) to a specific evacuation center by this method.

- Figure 13 is the result of the point-to-layer analysis. It is possible to analyze the route from a specific evacuation source (residential locations) to multiple evacuation centers by this method.

2.4.4. Evaluation of Practical Applicability

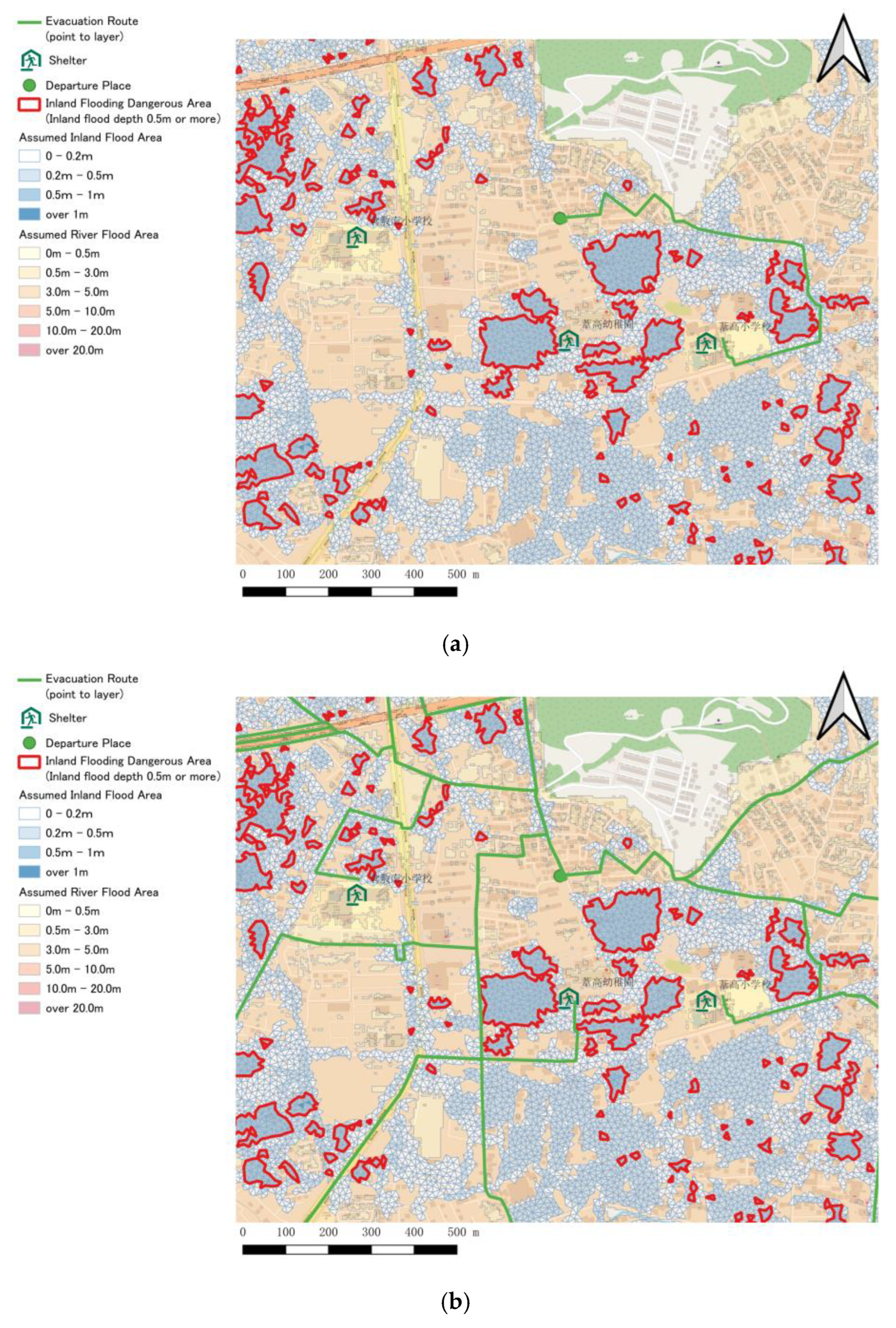

- Scenario 1 (No hazardous areas): The routes generated by the conventional method and the proposed method are identical, confirming that the new algorithm maintains efficiency when no risks are present.

- Scenario 2 (Hazardous areas present): The proposed method successfully generates alternative routes that detour around dangerous segments (depth ≥ 0.5 m), whereas the conventional method directs evacuees through these high-risk zones.

- Scenario 3 (Unavoidable hazards): The conventional method still generates a path crossing the hazard, while the proposed method returns no result (pathfinding failure). In such extreme cases, this failure signal serves as a critical warning that vertical evacuation (sheltering in place) or early evacuation is the only viable option.

3. Results

3.1. Flood-Affected Road Network Overview

3.2. Comparison Between Conventional and QGIS-Based Routes

3.3. Visualization of Evacuation Routes

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Significance of the Method

4.2. Comparison with Existing Approaches

4.3. Limitations and Future Improvements

4.4. Summary

5. Conclusions

6. Future Work

- Collecting more detailed shelter data (such as usable floor heights, facilities, size, capacity, etc.) and displaying them on a map.

- The capacity of the evacuation shelter can be evaluated by analyzing it in conjunction with the statistics of the surrounding population; it can also be compiled into a map for easy reference when taking evacuation actions.

- Cataloging places that can be used as temporary shelters (e.g., shopping malls, etc.) when nearby shelters exceed capacity or when there are no shelters nearby that can be safely accessed.

- The reliability of evacuation routes has not been verified in this study. We plan to evaluate the performance of evacuation routes in the future through simulations using past flood data.

- We will select more countries and regions to verify the generalizability of the proposed method.

- For people with special needs, such as children, the elderly, and the disabled, we will provide more detailed route planning and evacuation indicators by further considering comprehensive factors such as movement speed, difficulty of movement, and shelter capacity.

- In parallel, a real-time road water depth detection system using radar and other sensing technologies is being developed, aiming to incorporate real-time analysis capabilities into the existing method to make the results safer and more reliable. Furthermore, there are plans to integrate AI to enhance the efficiency of data processing and computation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morisaki, Y.; Fujiu, M.; Takayama, J. Analysis of Flood Risk for Vulnerable People Using Assumed Flood Area Data Focused on Aged People and Infants. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundzewicz, Z.W.; Pińskwar, I. Are Pluvial and Fluvial Floods on the Rise? Water 2022, 14, 2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Court of Auditors. Special Report No 25 2018–Floods Directive: Progress in Assessing Risks, While Planning and Implementation Need to Improve; European Court of Auditors: Luxembourg, 2018; Available online: https://op.europa.eu/webpub/eca/special-reports/floods-directive-25-2018/en/ (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- AFREL-SR. What Are Internal Water Flooding & External Water Flooding? Countermeasures for Heavy Rain Disasters and Actions to Take When They Occur. AFREL-SR Knowledge Base. 30 November 2022 (Updated 13 March 2023). Available online: https://afrel-s.jp/knowledge/naisuigaisui/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Guo, K.; Guan, M.; Yu, D. Urban surface water flood modelling—A comprehensive review of current models and future challenges. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 2843–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Qu, L.; Zou, T. Quantitative Analysis of Urban Pluvial Flood Alleviation by Open Surface Water Systems in New Towns: Comparing Almere and Tianjin Eco-City. Sustainability 2015, 7, 13378–13398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojtek, M.; Moradi, S.; De Luca, D.L.; Petroselli, A.; Vojteková, J. Fluvial and pluvial flood hazard mapping: Combining basin and municipal scale assessment. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2024, 15, 2432377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OKAYAMA Soudan Shitsu. Disaster Prevention 03. OKAYAMA Soudan Shitsu Website. Available online: https://www.okayamasoudan.com/disaster_prevention03.html (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Weathernews Inc. Survey on Evacuation During Heavy Rainfall: Older People Tend Not to Move to Shelters. Weathernews–Otenki News. Published 1 September 2020. Available online: https://weathernews.jp/s/topics/202008/310215/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Weathernews Inc. Disaster Risk Reduction Survey 2018—West Japan Heavy Rainfall: ‘I’ll be Fine’ and More… 84% Did Not Evacuate. Weathernews–Otenki News. 31 August 2020. Available online: https://jp.weathernews.com/news/24579/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- JBpress; Asano, K.; Nishizaki, R.; Tanaka, W. Why is Evacuation Delay Repeatedly Occurring During Heavy-Rain Disasters? JBpress/Japan Innovation Review. Published 5 January 2022. Available online: https://jbpress.ismedia.jp/articles/-/68251/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Toyo Keizai Online; Hirofumi, T. Why People Fail to Evacuate Even After Evacuation Orders Are Issued: Four Guidelines Needed to Protect Oneself Against Heavy-Rain Disasters. Toyo Keizai Online. Published 15 July 2019. Available online: https://toyokeizai.net/articles/-/290914/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT). Implementation Status of Urban Pluvial Flooding Countermeasures after Guideline Formulation; Water Management and National Land Conservation Bureau, Sewerage Department, MLIT: Tokyo, Japan, 2019. Available online: https://www.mlit.go.jp/mizukokudo/sewerage/content/001378231.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Lee, Y.H.; Kim, H.I.; Han, K.Y.; Hong, W.H. Flood Evacuation Routes Based on Spatiotemporal Inundation Risk Assessment. Water 2020, 12, 2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, G.; Kim, J.O. Flood Evacuation Mapping Using a Time–Distance cartogram. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parajuli, G.; Neupane, S.; Kunwar, S.; Adhikari, R.; Acharya, T.D. A GIS-Based Evacuation Route Planning in Flood-Susceptible Area of Siraha Municipality, Nepal. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irsyad, H.A.W.; Hitoshi, N. Flood disaster evacuation route choice in Indonesian urban riverbank kampong: Exploring the role of individual characteristics, path risk elements, and path network configuration. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 81, 103275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. Guideline on Evacuation Information (Revised May 2021). Guideline on Evacuation Information Under the Disaster Countermeasures Basic Law. Available online: https://www.bousai.go.jp/oukyu/hinanjouhou/r3_hinanjouhou_guideline/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Kurashiki City & Okayama Prefecture. Kurashiki City Integrated GIS Portal. Okayama Prefecture Al Prefecture Integrated GIS Website. Available online: http://www.gis.pref.okayama.jp/kurashiki/Portal (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT). Use Case UC22-041. Project PLATEAU–Use Case Examples. Available online: https://www.mlit.go.jp/plateau/use-case/uc22-041/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Nomad Season. Climate of Okayama (July)–Kurashiki & Okayama, Japan/Monthly Climate Data. Nomad Season Website. Available online: https://nomadseason.com/weather/japan/okayama/kurashiki-july.html (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Climate-Data.org. Weather Kurashiki & Temperature By Month–Japan/Okayama Prefecture/Kurashiki. Climate-Data.org. Available online: https://en.climate-data.org/asia/japan/okayama-prefecture/kurashiki-5325/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- CityPopulation.de. Kurashiki City (Okayama Prefecture)–Population Statistics, Charts & Map. CityPopulation.de. Available online: https://www.citypopulation.de/en/japan/okayama/_/33202__kurashik (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Peace Boat Disaster Relief Volunteer Center. Emergency Response: Japan Floods 2018 [Update]. Peace Boat Disaster Relief–News. Published 18 July 2018. Available online: https://pbv.or.jp/en/news/emergency-response-japan-floods-2018/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Introduction of QGIS. Available online: https://blog.csdn.net/qq_35662333/article/details/136150624 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- QGIS Development Team. QGIS User Guide: Network Analysis (Version 3.40). QGIS Documentation. 2025. Available online: https://docs.qgis.org/3.40/en/docs/user_manual/processing_algs/qgis/networkanalysis.html (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- QGIS Development Team. QGIS PyQGIS Developer Cookbook: Network Analysis (Version 3.40). QGIS Documentation. 2025. Available online: https://docs.qgis.org/3.40/en/docs/pyqgis_developer_cookbook/network_analysis.html (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Arrighi, C.; Oumeraci, H.; Castelli, F. Hydrodynamics of pedestrians’ instability in floodwaters. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 21, 515–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Xia, J.; Li, Q.; Zhou, M. Risk assessment for people and vehicles in an extreme urban flood: Case study of the ‘7.20’ flood event in Zhengzhou, China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 80, 103205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Zhang, S.; Bao, J.; Zhao, H. Evaluation of evacuation difficulty of urban resident during storm water-logging based on walking experiment. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2022, 15, e12850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardini, G.; Quagliarini, E. How to Account for the Human Motion to Improve Flood Risk Assessment in Urban Areas. Water 2020, 12, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio Uribe, C.H.; Russo, B.; Téllez-Álvarez, J.; Martínez-Gomariz, E. Flood-Related Hazard Criteria During the Human Evacuation of Underground Spaces Through Stairs: A State-of-the-Art Review. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 5035–5073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Alert Level | New Evacuation Information | Previous System of Evacuation Information | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Disaster occurrence | Emergency Safety Measures | Disaster occurrence information (Issued once occurrence is confirmed) |

| <Be sure to evacuate by Alert Level 4!> | |||

| 4 | High risk | Evacuation Instruction | -Evacuation Instruction (emergency) -Evacuation Recommendation |

| 3 | Risk of disaster | Evacuation of the Elderly, Etc. | Advisory to prepare for evacuation and start evacuating elderly and other persons requiring special care. |

| 2 | Weather worsening | Heavy Rain, Flood, or Storm Surge Advisories (Japan Meteorological Agency) | Heavy Rain, Flood, or Storm Surge Advisories (Japan Meteorological Agency) |

| 1 | Risk of weather worsening | Probability of Warnings (Japan Meteorological Agency) | Probability of Warnings (Japan Meteorological Agency) |

| Method | Free Software | Disaster Types Displayed | Hazard Avoidance | 3D/2D | Real-Time Data Update | Multi-Destination Route Planning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QGIS | Yes | Flood & Inland flood | Yes | 2D | No | Yes |

| GIS Maps (Government) | Yes | Flood & Inland flood | No | 2D | No | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pan, W.; Pan, S.; Kaneto, J.; Yoshida, K.; Nishiyama, S. An Integrated QGIS-Based Evacuation Route Optimization Approach for Disaster Preparedness Against Urban Flood in Japan. Geographies 2025, 5, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies5040074

Pan W, Pan S, Kaneto J, Yoshida K, Nishiyama S. An Integrated QGIS-Based Evacuation Route Optimization Approach for Disaster Preparedness Against Urban Flood in Japan. Geographies. 2025; 5(4):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies5040074

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Wenliang, Shijun Pan, Junko Kaneto, Keisuke Yoshida, and Satoshi Nishiyama. 2025. "An Integrated QGIS-Based Evacuation Route Optimization Approach for Disaster Preparedness Against Urban Flood in Japan" Geographies 5, no. 4: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies5040074

APA StylePan, W., Pan, S., Kaneto, J., Yoshida, K., & Nishiyama, S. (2025). An Integrated QGIS-Based Evacuation Route Optimization Approach for Disaster Preparedness Against Urban Flood in Japan. Geographies, 5(4), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies5040074