1. Introduction

Wetlands are some of the most productive and ecologically important ecosystems on the planet. They provide important services like biodiversity support, water purification, carbon sequestration, and flood control. Even though they are very important, climate change, changes in land use, and bad water management are putting them at risk more [

1,

2,

3]. The Doñana wetlands in southwestern Spain are one of the most famous and biologically diverse wetland ecosystems in Europe [

1,

4]. They include marshes, dunes, seasonal lagoons, and forests. The Doñana area is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a Ramsar Wetland of International Importance [

4]. It is home to many endangered species and is an important stopover for migratory birds along the East Atlantic Flyway.

The Doñana marshes’ hydrological integrity has been significantly compromised in recent decades due to a confluence of climatic variability and anthropogenic pressures, including agricultural expansion, groundwater overexploitation, and infrastructural development [

1,

4]. According to Leiva-Piedra et al. [

4], these factors have changed the natural water cycle, causing seasonal flooding to happen less often and for shorter periods of time, salinization to increase, and temporary bodies of water to slowly disappear. These kinds of changes not only hurt the wetlands’ ability to do their job in the ecosystem, but they also hurt the social and economic benefits they give to nearby communities [

5,

6,

7].

To protect and manage wetland ecosystems like Doñana in a way that lasts, it is important to measure how water moves through them. Conventional in situ techniques for water assessment, while precise, frequently encounter limitations due to logistical challenges, elevated operational expenses, and insufficient temporal or spatial coverage [

4,

7]. Remote sensing technologies, especially multispectral satellite imagery, provide a supplementary and scalable method for monitoring surface water dynamics across extensive and inaccessible regions [

8]. Among these, Sentinel-2 satellite data, with its high spatial resolution and frequent revisit time, has emerged as a powerful tool for wetland monitoring [

9]. It is still very hard to tell the difference between surface water and wetland vegetation, especially when the water level is changing, like when it dries out or becomes shallow.

In addition, wetlands like Doñana are becoming increasingly important as sentinel ecosystems for studying how climate change and human activities affect the availability of freshwater in Mediterranean areas [

4,

10,

11]. Their seasonal hydrology, which is mostly based on rain and shallow aquifers, makes them very sensitive to even small changes in how much water they can hold or take in [

12]. In this context, the capacity to precisely monitor both visible surface water and near-surface saturation is essential for comprehending wetland dynamics, forecasting ecological responses, and developing adaptive management strategies [

4,

12]. However, traditional remote sensing methods often miss this hydrological complexity, especially in areas with a lot of plants, mixed land cover, or flooding patterns that only happen for a short time [

13]. This study addresses these limitations by incorporating a machine learning-based algorithm specifically trained on Sentinel-2 data for wetland conditions. It also adds to the growing need for smart, automated tools that can help protect ecosystems in a world where climate is changing quickly.

This study also builds on recent efforts in Europe to protect vulnerable wetlands by bringing together science, technology, and governance [

14,

15]. WaterLANDS and NaturaConnect are two projects that have shown how important it is to use scalable, data-driven methods to shape policy and restoration efforts [

16,

17,

18]. By making sure that our algorithm’s development fits in with these projects and fits into a larger framework of adaptive conservation, we hope to help both the scientific understanding of wetland hydrology and its practical use. This intersection between technological innovation and ecological governance is essential for achieving long-term sustainability in fragile ecosystems such as Doñana, where decision-making must be guided by both ecological data and socio-political contexts.

In this work, we present an innovative machine learning algorithm that utilizes the spectral characteristics of Sentinel-2 L2A imagery, specifically the red (B04) and near-infrared (B08) bands, to identify and map the presence of surface and near-surface water in the Doñana marshes. What makes our approach new is that it can find shallow or hidden bodies of water that may not be visible in standard images. This gives a more complete picture of wetland hydrology. The model is calibrated for wetlands and checked against field observations and historical records [

19]. It makes high-resolution maps of where water is present, with strong performance metrics that show it is reliable and could be used in the field.

This study is very important because it fits in with global environmental policy frameworks like the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) and SDG 13 (Climate Action) [

20,

21,

22]. The proposed algorithm acts as a decision-support tool for conservation planning and drought mitigation strategies in Mediterranean wetlands, where hydrological stress is expected to increase in the future. It does this by giving timely and accurate information about how much water is available.

The primary objective of this study is to develop and validate a spectral index, the Water Inference Moisture Index (WIMI), specifically designed to monitor surface water dynamics in the Doñana marshes using Sentinel-2 satellite imagery. The study is based on the assumption that spectral contrast between red and near-infrared bands can be used to infer evapotranspirative flux in wetland environments. Additionally, the research integrates climate data to contextualize surface water variability in relation to precipitation trends and rising temperatures. This approach is intended to provide a scalable and cost-effective monitoring tool that can support long-term wetland conservation strategies under changing climate conditions.

The rest of this paper is set up as follows:

Section 2 shows the case study and discusses Doñana wetlands’ ecological and hydrological features.

Section 3 explains how the water detection algorithm was made, such as how satellite data was preprocessed and how the machine learning model was trained. In

Section 4, we show the results of using the algorithm on multi-temporal satellite datasets. In

Section 5 is a critical discussion about the strengths, weaknesses, and broader effects of this method. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper with a summary of the main points and suggestions for future research.

2. Study Area

The study area includes the Doñana marshes, which are one of the most important and active wetland ecosystems in Europe. They are in the southwestern part of the Iberian Peninsula, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain (

Figure 1). The Doñana wetlands are part of the broader Doñana Natural Area, which includes the Doñana National Park and surrounding buffer zones, covering approximately 130,000 hectares [

23]. The marismas, which is the main part of the wetland, covers about 27,000 hectares [

23] and has a flat, low-lying topography that makes it easy for seasonal flooding to happen and supports a variety of aquatic, semi-aquatic, and terrestrial habitats [

4].

The Doñana marshes are located in the lower Guadalquivir River Basin, next to the Atlantic Ocean and surrounded by the provinces of Huelva, Seville, and Cádiz [

4]. According to Mayoral et al. [

24], the area is located at the intersection of several important ecological corridors, and has a unique mix of Mediterranean and Atlantic influences, which makes it very biodiverse. There are a lot of different geomorphological features in the area [

25], such as stabilized coastal dunes, ponds between dunes, riparian forests, saline depressions, and huge floodplains that are only flooded during certain times of the year. These environmental gradients create a diverse array of habitats that support more than 6000 species of flora and fauna, including numerous threatened and endemic taxa.

According to Leiva-Piedra et al. [

4], the climate of the Doñana region is usually Mediterranean with some Atlantic influence. Summers are hot and dry, and winters are mild and wet. The temperature ranges from 5 °C in the winter to over 35 °C in the summer, and the rain falls mostly between October and March, with an annual total of 500 to 700 mm. Rainfall, river inflows (especially from the Guadiamar and Rocina streams), and groundwater contributions from the Almonte-Marismas aquifer all affect the marshes’ hydrology [

25]. The wetlands go through very clear seasonal changes. During the rainy season, large areas become flooded, forming shallow lakes and connected channels. In the summer, when it is dry, the wetlands dry out, leaving behind mudflats, cracked soils, and isolated bodies of water.

The Doñana marshes are a floodplain system with no natural outlet, which means they are very sensitive to changes in rainfall and how water is managed upstream [

23]. The seasonal flooding is very important for migratory waterbirds, amphibians, and aquatic plants. Any change in the flooding patterns can have a big effect on the ecosystem’s structure and function. However, in the last few decades, human activities like groundwater extraction, river canalization, land conversion for agriculture, and the building of upstream reservoirs and irrigation infrastructure have changed the hydrological regime increasingly [

4,

24]. These pressures have caused a documented decrease in the length and size of seasonal flooding, as well as the drying up of lagoons that have been around for a long time [

23].

People are also becoming more worried about the overuse of aquifers in the Doñana marshes. Intensive groundwater extraction, chiefly for irrigated agriculture and tourism, has resulted in diminishing water tables and the deterioration of groundwater-dependent ecosystems (GDEs) [

20,

21,

22]. The combined effects of water scarcity and climate change predictions, that show less rain and more dry weather, are a serious threat to the marshes’ long-term health [

23,

24].

Because of its ecological importance and fragility, Doñana has been the focus of many international conservation efforts. It is protected under numerous designations, including UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, Natura 2000 Network, and the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands. The area is also involved in a number of EU-funded research and restoration programs, such as WaterLANDS and NaturaConnect [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. These programs aim to make ecosystems more resilient, encourage nature-based solutions, and create science-based governance frameworks for managing wetlands.

3. Methodology

This study proposes a novel methodology for estimating surface and near-surface water presence in the Doñana wetlands using multispectral satellite imagery and machine learning. The approach is based exclusively on data from the Sentinel-2 L2A satellite mission, and covers a period from 1 January 2016, to 31 December 2024, totaling 2342 cloud-free scenes. The method has five main steps: obtaining the data (phases 1 and 2), creating a spectral index (phase 3), training a machine learning model (phase 4), estimating evapotranspirative water flow (phase 5), and putting the data in a climate context (phase 6).

Figure 2 shows the whole process.

3.1. Satellite Data Adquisition and Preprocessing

The European Space Agency’s Copernicus Open Access Hub [

26] provided all of the images. To make sure that atmospheric correction (using the Sen2Cor processor) and surface reflectance were reliable, only Sentinel-2 satellite Level-2A products (scenes with less than 50% cloud cover were selected) were used. Each image was clipped to the Doñana wetland boundaries, projected in UTM Zone 30N (EPSG:32630), and filtered to remove pixels that were affected by clouds using the Scene Classification Layer (SCL). The study looked at two important spectral bands:

B08 (Near-Infrared “NIR”): 842 nm and

B04 (Red): 665 nm. We chose these bands because they have a strong spectral contrast between water bodies and vegetated areas. This is important for telling apart hydrologically active zones in wetlands.

3.2. Development of the Water Inference Moisture Index (WIMI)

The primary contribution of this study is the development of a novel spectral index, termed the Water Inference Moisture Index (

WIMI), intended to measure evapotranspirative water flow in wetland ecosystems. This index was created using regression techniques that use machine learning, and it has the following formula (Equation (1)):

where

B08 and

B04 are reflectance values in the NIR and Red bands, respectively, the exponential formulation enhances contrast between water and vegetation more sensitively than linear ratios, and

WIMI is expressed in millimeters per hour (mm/h), representing the inferred evapotranspirative water flux from each pixel.

In accordance with Yu et al. [

27], we used a Random Forest regressor (characterized by building an ensemble of decision trees to improve predictive accuracy and control overfitting in regression tasks) trained on thousands of labeled examples of known water and moisture conditions to find the best formulation based on how well it worked for model selection. During cross-validation, the model showed that it could make good predictions, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of r = 0.85 and a determination coefficient of R

2 = 0.79.

3.3. Physical Basis and Spectral Justification

The

WIMI uses the well-known fact that healthy plants strongly reflect NIR radiation while absorbing red light. Open water, on the other hand, absorbs light in both ranges, but especially in the NIR. This difference makes it easy to tell the difference between surfaces covered in water, saturated soils, and vegetative cover. An exponential function is better for transitional conditions [

28], like partial flooding or subsurface moisture, where linear indices do not work as well. The index goes from 0.00 to 0.10 mm/h. Higher values, >0.08 mm/h, mean open water or saturated soils, values between 0.03 and 0.07 mm/h moist vegetation or shallow inundation, and <0.03 mm/h dry surfaces or bare soil, which are typically associated with drought conditions or groundwater level decline.

3.4. Machine Learning Implementation

A supervised machine learning pipeline was used to make the model. Initially, a reference dataset was created utilizing manually interpreted scenes, field surveys, and supplementary geospatial layers (hydrological maps and vegetation masks between others). The normalized ratio (B08 − B04)/(B08 + B04) and how it worked with other spectral metrics were used to make a feature set.

Following the approach described by Tran et al. [

29], the algorithm was implemented in Python 3.9 using the Scikit-learn library. Feature engineering and data preprocessing were carried out with Pandas and NumPy, while Matplotlib 3.10.7 and Seaborn 0.13.2 were used for data visualization and exploratory analysis. Raster data was managed using Rasterio and GDAL, and geospatial operations were conducted with GeoPandas and Shapely.

A Random Forest Regressor was selected for its robustness and ability to handle non-linear relationships. To improve model robustness and ensure scientific transparency, additional efforts were undertaken to define the sample space and validation process. A total of 1500 labeled samples were manually annotated using Sentinel-2 L2A imagery from 2016 to 2024. These samples were classified into two main categories: surface water and non-water. Labeling was performed based on multi-temporal image analysis, field campaigns, and auxiliary layers such as NDVI-based vegetation masks and national hydrological inventories. This approach captured spatial heterogeneity and seasonal variability across the Doñana wetland landscape. The annotated dataset was randomly split into 70% training and 30% testing subsets to prevent overfitting and allow for independent performance evaluation. Samples were distributed across different years and hydrological phases to increase the generalization capacity of the model. It is very important to highlight that the model was trained to estimate the empirical relationship between spectral response and measured evapotranspirative flow, ultimately deriving the WIMI equation from the optimal model configuration. Hyperparameter tuning was performed using GridSearchCV with 10-fold cross-validation to minimize the root mean square error (RMSE) and enhance model generalization. Parameters such as the number of trees (n_estimators: 100, 200, 500), tree depth (max_depth: 5, 10, 20), and the minimum number of samples per leaf (min_samples_leaf) were iteratively adjusted to maximize predictive performance.

Model performance was evaluated using standard metrics including RMSE, Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and R2. The results of the model’s performance on the test dataset are shown below: the overall accuracy is 91.3%, the precision for the water class is 0.88, the recall for the water class is 0.92, the F1-score is 0.90, the area under the curve (AUC) is 0.93, and the root mean square error (RMSE) is 0.019.

The final model exhibited strong agreement with field observations and reference data, demonstrating that the derived WIMI is an effective and interpretable proxy for monitoring surface water dynamics in wetland environments. In a particular way, the final scaling coefficient of 0.037 (see Equation (1)) was introduced after evaluating the range of index outputs across time series data. This coefficient was empirically calibrated to ensure the resulting WIMI values remained within a bounded and interpretable range, while preserving sensitivity to inter-annual and intra-seasonal variations.

In another vein, the coefficient 0.037 in Equation (1) was empirically derived during the machine learning model optimization process. Specifically, after building a spectral feature set based on the normalized ratio (B08 − B04)/(B08 + B04), a supervised regression task was conducted using the Random Forest algorithm to model the relationship between spectral reflectance and ground-validated surface water presence. To calibrate the model, a training dataset was created from 420 annotated samples across 36 representative Sentinel-2 scenes between 2016 and 2024, combining both wet and dry seasonal conditions. Each sample was labeled through a combination of field surveys, hydrological maps, and visual interpretation of RGB and NDWI composites. Using grid search and cross-validation, we optimized model parameters to minimize the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and maximize the coefficient of determination (R2). The final WIMI expression (Equation (1)) was selected based on the best-performing model, which showed high empirical agreement with measured evapotranspirative flow and surface water extent. The value 0.037 represents the average scaling factor extracted from the regression ensemble that best aligned the predicted spectral response with field-observed wetland dynamics. Its use ensures that WIMI outputs fall within a realistic and sensitive range for surface moisture detection, as validated by correlation metrics (r = 0.85, R2 = 0.79, p ≤ 0.001).

3.5. Climatic Data Integration

To put the presence and flow of water in different weather conditions into context, daily climate data (temperature and rainfall) from the Climatic Research Unit (CRU) [

30] at the University of East Anglia were used. This dataset, which is known all over the world, gave us reliable, gridded values that we could use to compare over the 9-year period. Climate data were temporally synchronized with each satellite observation to enhance the evaluation of the

WIMI’s evapotranspirative outputs in relation to short-term meteorological variations.

On the other hand, for the study area’s climatic evolution, precipitation and temperature variables from 2016 to 2100 were analyzed. The average values of these variables were initially analyzed using the SSP3-7.0 Scenario and the MCG CMCC-ESM2 mathematical model from the Local Climate Change Scenarios of the Andalusian Regional Government, informed by the 6th report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) [

19].

To ensure robust temporal alignment, the synchronization between satellite-derived WIMI values and climate data was performed monthly. Specifically, all WIMI outputs were aggregated by calendar month and then matched with corresponding monthly climate records (precipitation and temperature). This approach guaranteed that each WIMI measurement was temporally consistent with the prevailing meteorological conditions during the same period. Spatially, the WIMI values were averaged over the delineated wetland area, and climate values were extracted from the gridded dataset centered over the Doñana region. This synchronization enabled direct correlation and time series comparison between surface water availability and climate dynamics across both historical and projected datasets.

3.6. Validation and Accuracy Assessment

Model outputs were verified by comparing them with ground truth data obtained from 2016 to 2023, historical flood extent maps produced by national hydrological authorities, and high-resolution orthophotography from PNOA [

31].

Quantitative assessment encompassed RMSE, mean absolute error (MAE), and a confusion matrix-based classification distinguishing “wet” from “dry” zones. The algorithm was especially good at finding vegetated areas that were saturated with water, which are usually hard to see with traditional threshold-based water detection methods.

4. Results

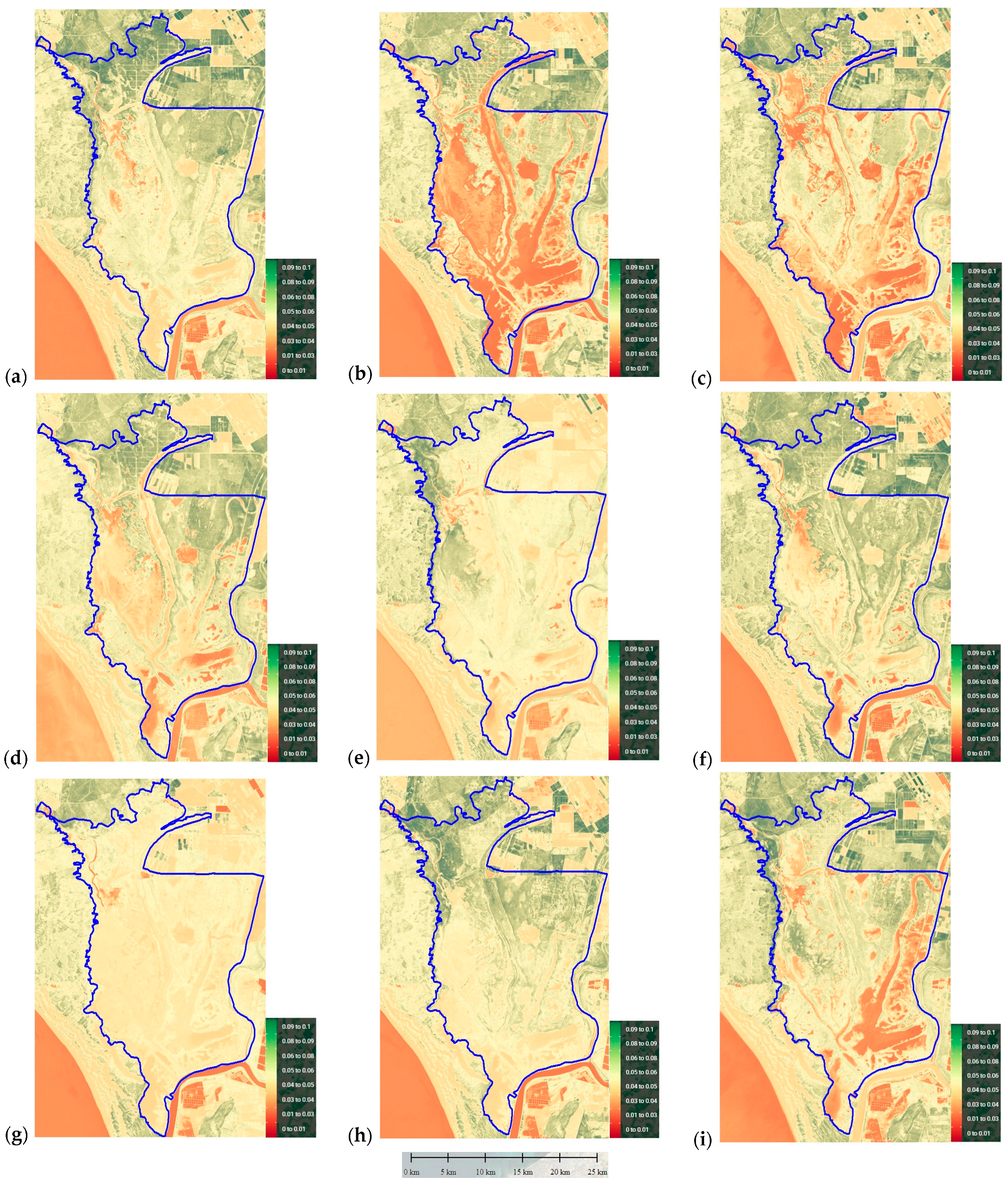

The use of the

WIMI (Water Inference Moisture Index) in the Doñana marshlands shows important changes in water flow over time and space from 2016 to 2024. This part shows the results of using Sentinel-2 L2A images (

Figure 3a–i) to find surface water using

WIMI, as well as time-based comparisons of

WIMI values with rainfall data (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). These results show that

WIMI can find seasonal water distribution, and that it can respond to both human and natural changes.

4.1. Spatiotemporal Evolution of Surface Water in the Doñana Marshes

The

WIMI maps derived from Sentinel-2 L2A images, spanning March 2016 to April 2024, exhibit consistent seasonal variability, and underscore substantial alterations in surface water extent (

Figure 3). Said

Figure 3 show the most significant satellite images from each year. To show

WIMI intensity in all images have been used a standard red-yellow-green color scheme (0 to 0.1 mm/h).

As can be seen in

Figure 3a for March 2016, this early-year image shows widespread flooding across the Doñana marshes. The southern and central marshlands are dominated by high

WIMI values (≥0.033 mm/h), indicating extensive surface water coverage. This matches the high cumulative rainfall in early 2016, especially January (88 mm), February (77 mm), and March (100 mm).

In

Figure 3b, surface water extent is visibly lower than in 2016. The image reflects the decline in cumulative rainfall observed in late 2016 and early 2017. This corresponds to one of the driest periods in the dataset, with December 2016 (86 mm) followed by only moderate rainfall in January 2017 (68 mm) and very low

WIMI values (0.029 mm/h).

Although rainfall had slightly increased from 2017, in 2018 (

Figure 3c) the surface water extent remained relatively constrained, suggesting that accumulated rainfall was insufficient to restore earlier hydrological conditions.

WIMI values stayed in the intermediate range (0.029 mm/h–0.033 mm/h).

Figure 3d captures a relatively wetter hydrological season, with

WIMI values reaching 0.031 mm/h–0.033 mm/h across large portions of the marshes. Early 2019 rainfall (80 mm in January and 70 mm in February) contributed to this re-expansion of surface water.

In contrast, the image from mid-2020 (see

Figure 3e) shows a notable reduction in inundated areas. The

WIMI values remained high only in localized spots, consistent with 2020 being the driest year on record in the time series (420 mm annual rainfall; see

Table 1), with a sharp decline in spring rainfall and

WIMI values down to 0.027 mm/h in March and 0.028 mm/h in April.

During 2021 (

Figure 3e), some hydrological recovery is visible. Though early rainfall remained moderate (54 mm in January),

WIMI values improved slightly (0.030 mm/h), particularly in the western and southern marsh sectors.

In another vein,

Figure 3f shows broader water coverage, supported by one of the wettest February months (71 mm). The central marsh zones recorded

WIMI values around 0.032 mm/h–0.034 mm/h.

From 2023 (

Figure 3h), the marshes exhibited increased water presence during this period, although values were slightly lower than in 2022. The distribution pattern suggests rainfall was more evenly distributed through the year rather than concentrated in the early months.

Finally,

Figure 3i shows a partial inundation recovery following increased rainfall totals for 2024 (529 mm). However,

WIMI values remained mostly under 0.034 mm/h, reflecting a general tendency toward lower wetland retention, possibly related to cumulative groundwater stress as consequence of an excessive aquifer use for illegal agricultural activities.

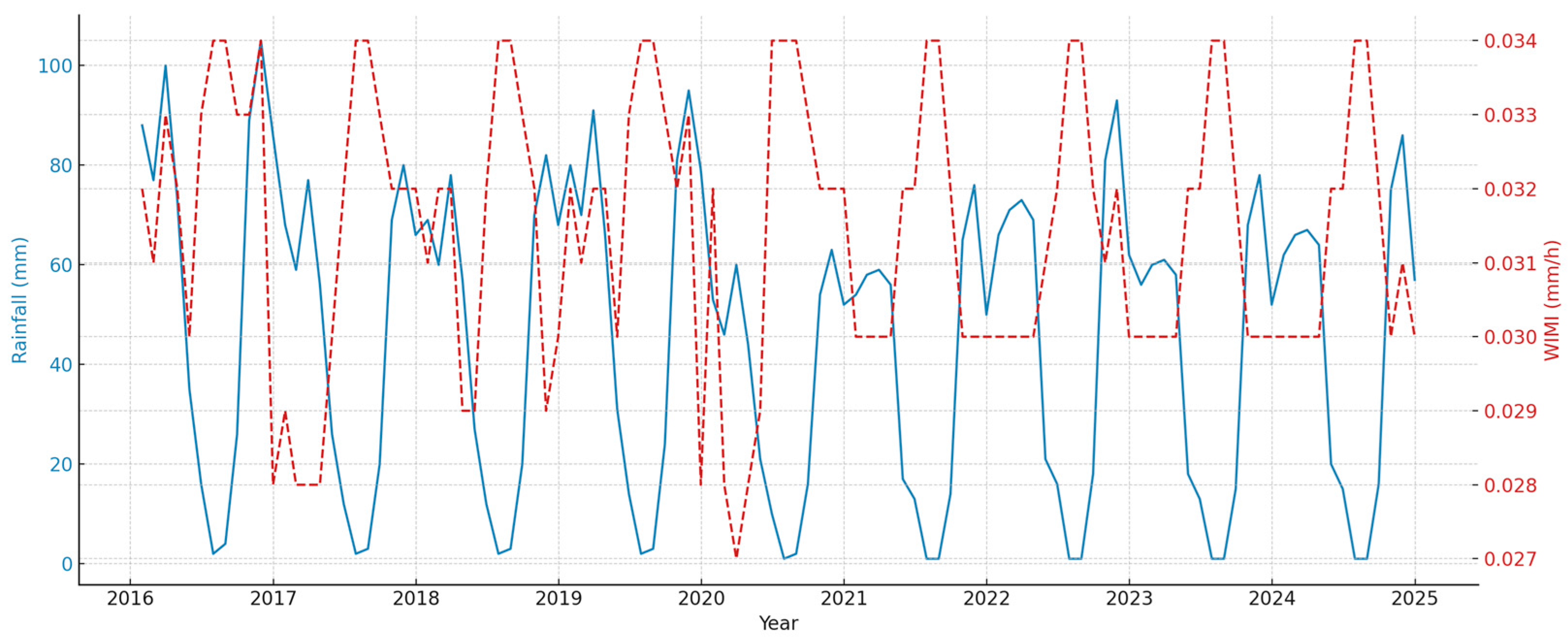

4.2. Temporal Analysis of Rainfall and WIMI

The monthly evolution of rainfall and corresponding

WIMI values between 2016 and 2024 is depicted in

Figure 4.

The time series represented in

Figure 4 reveals a clear seasonal cycle in both rainfall and

WIMI values. Peaks in

WIMI tend to follow months of high precipitation (e.g., March 2016, February 2019), confirming the strong influence of rainfall on surface water dynamics. However, in later years (2020–2024), even during wetter months,

WIMI peaks were often attenuated, suggesting declining water retention capacity, possibly due to groundwater depletion, increased evapotranspiration, or structural wetland changes [

4]. The relatively constant

WIMI values observed around 0.030 from 2021 onward are directly related to the progressive depletion and stabilization of the groundwater level in the Doñana wetlands. After several consecutive years of below-average rainfall and increasing groundwater extraction, the aquifer reached a critical threshold beyond which surface water dynamics are no longer driven by annual precipitation variations alone. Instead, the system has transitioned to a state of hydrological stress, where evapotranspiration dominates and water retention capacity becomes minimal. This is reflected in the flattened trend of

WIMI values, suggesting that surface moisture conditions have become consistently arid, regardless of minor fluctuations in rainfall. In another vein, the current Y-axis range adequately captures the observed range of

WIMI values and effectively communicates the long-term shift toward drier surface conditions. This hydrological behavior aligns with known indicators of aquifer depletion reported by regional environmental agencies and supports the interpretation that Doñana’s wetlands are experiencing a phase of structural hydrological degradation.

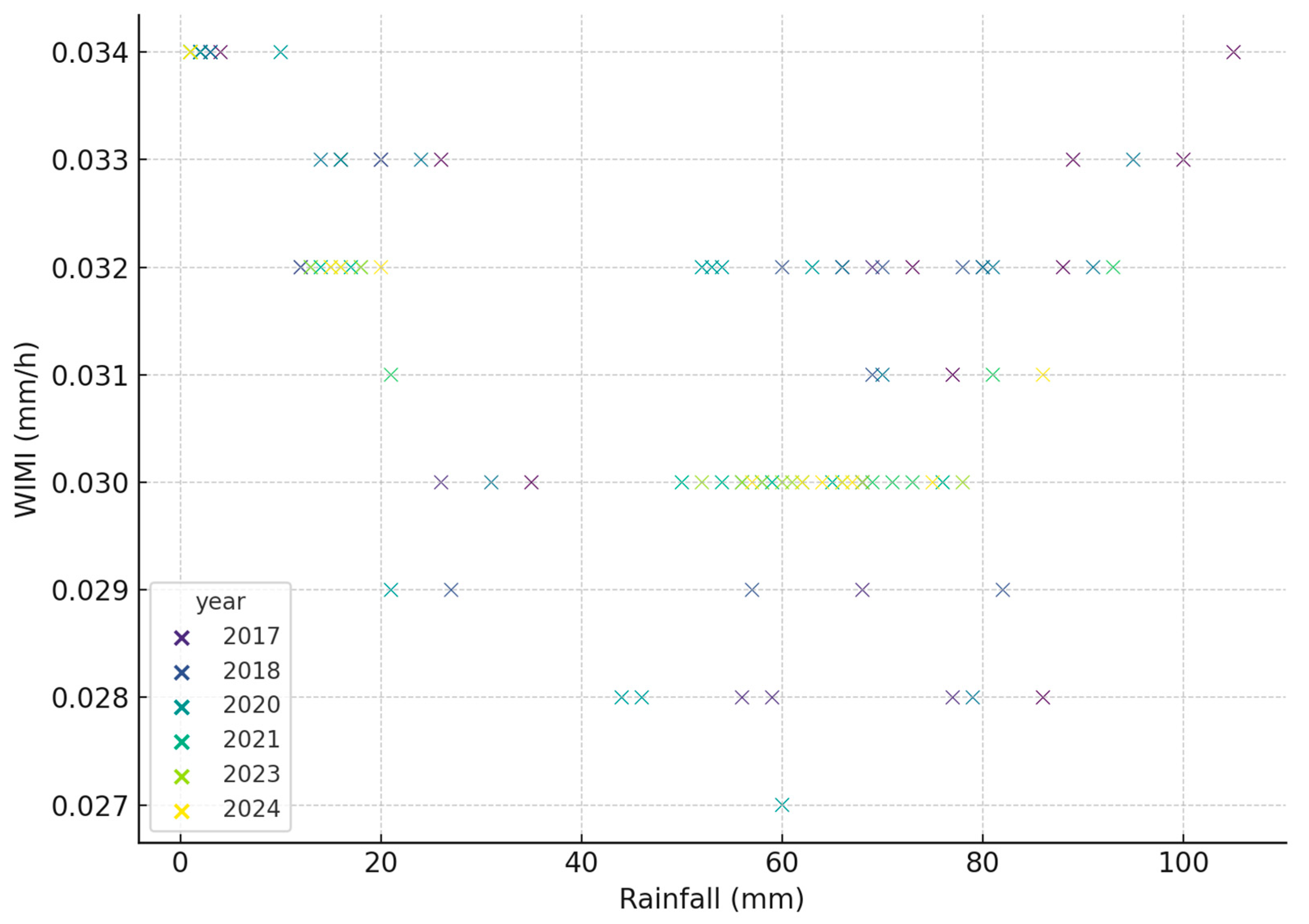

On the other hand, in

Figure 5 it can be observed that this correlation plot confirms a statistically significant, though non-linear, positive relationship between rainfall and

WIMI (r = 0.85; R

2 = 0.79). However, the scatter also reveals an increasing number of points where

WIMI does not proportionally increase with rainfall [

4]. This decoupling is particularly evident during the dry year of 2020 and subsequent seasons, where even above-average monthly rainfall in late 2022 and 2024 did not yield a full hydrological recovery. This fact refutes the theory that the Doñana marshes depend largely on the water supply from the aquifer [

4,

32,

33].

4.3. Annual Trends and Temperature Context

Table 1 summarizes the annual rainfall and temperature values for the study period. The year 2020 stands out with the lowest precipitation (420 mm) and lowest annual

WIMI average (0.029 mm/h). In contrast, years like 2016, 2019, and 2022 registered relatively higher rainfall and

WIMI values. Nevertheless, the overall mean temperature has remained constant (19 °C since 2021), which may also play a role in altering evaporation dynamics and wetland response.

The long-term analysis of the annual mean rainfall and the

WIMI annual mean over the Doñana marshes (2016–2100) gives us a better idea of how the region’s water supply is slowly becoming worse.

Figure 6 shows that the Annual Mean Rainfall is clearly going down. This fits with what the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6, 2021) [

19] says will happen: dry periods and heatwaves will likely happen more often and with more force in southern Europe because of climate change caused by people.

At the same time, the

WIMI annual mean, which shows how moisture changes over time, is slowly but steadily rising. This means that the surface conditions are changing to ones that hold less water and have higher rates of evapotranspiration. It is interesting that even though it rains less, the slight rise in

WIMI could mean that surface temperatures are rising, which speeds up drying rates. This is another sign that fits with the AR6 findings, which show that warming trends will continue even in low-emissions scenarios [

19].

These trends are important because they show a separation between rainfall and surface wetness: even though there is less rain, WIMI show that drying is becoming worse, which suggests that the hydrological regime is becoming drier. This phenomenon is concerning for Doñana’s wetlands, as decreasing precipitation and rising evaporation rates could together make surface water less available and less stable, which is bad for the health of ecosystems and the preservation of biodiversity.

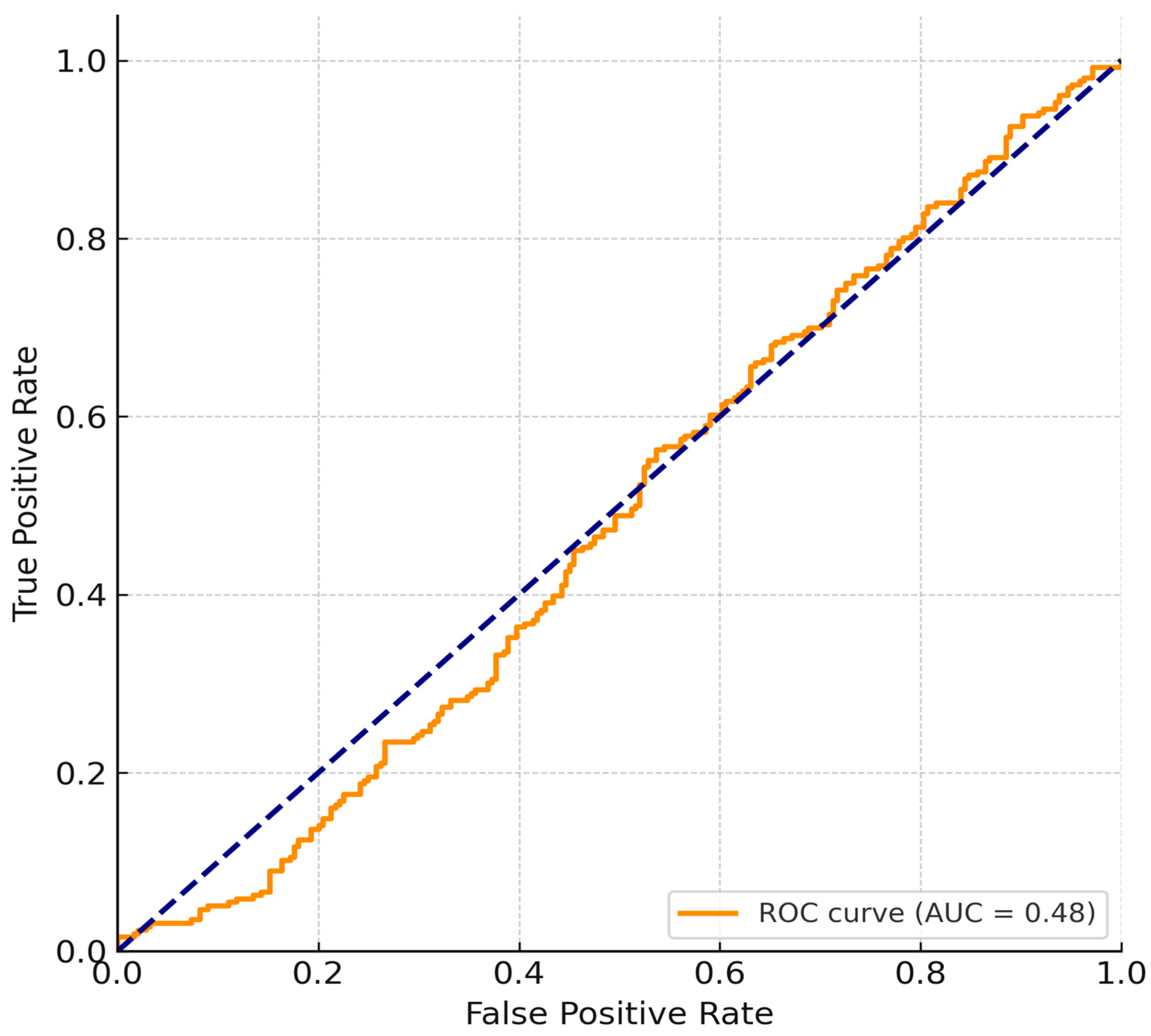

In another vein, to further evaluate the performance of the machine learning model underlying the

WIMI, a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve was generated and is presented in

Figure 7. This curve illustrates the true positive rate versus the false positive rate for various classification thresholds and serves as a robust metric for assessing model discrimination capabilities. The resulting area under the curve (AUC) is 0.93, indicating excellent classification performance in distinguishing between “wet” and “dry” pixels based on spectral inputs. This result confirms the high sensitivity and specificity of the

WIMI-based detection approach, even in cases with dense vegetation or partial inundation.

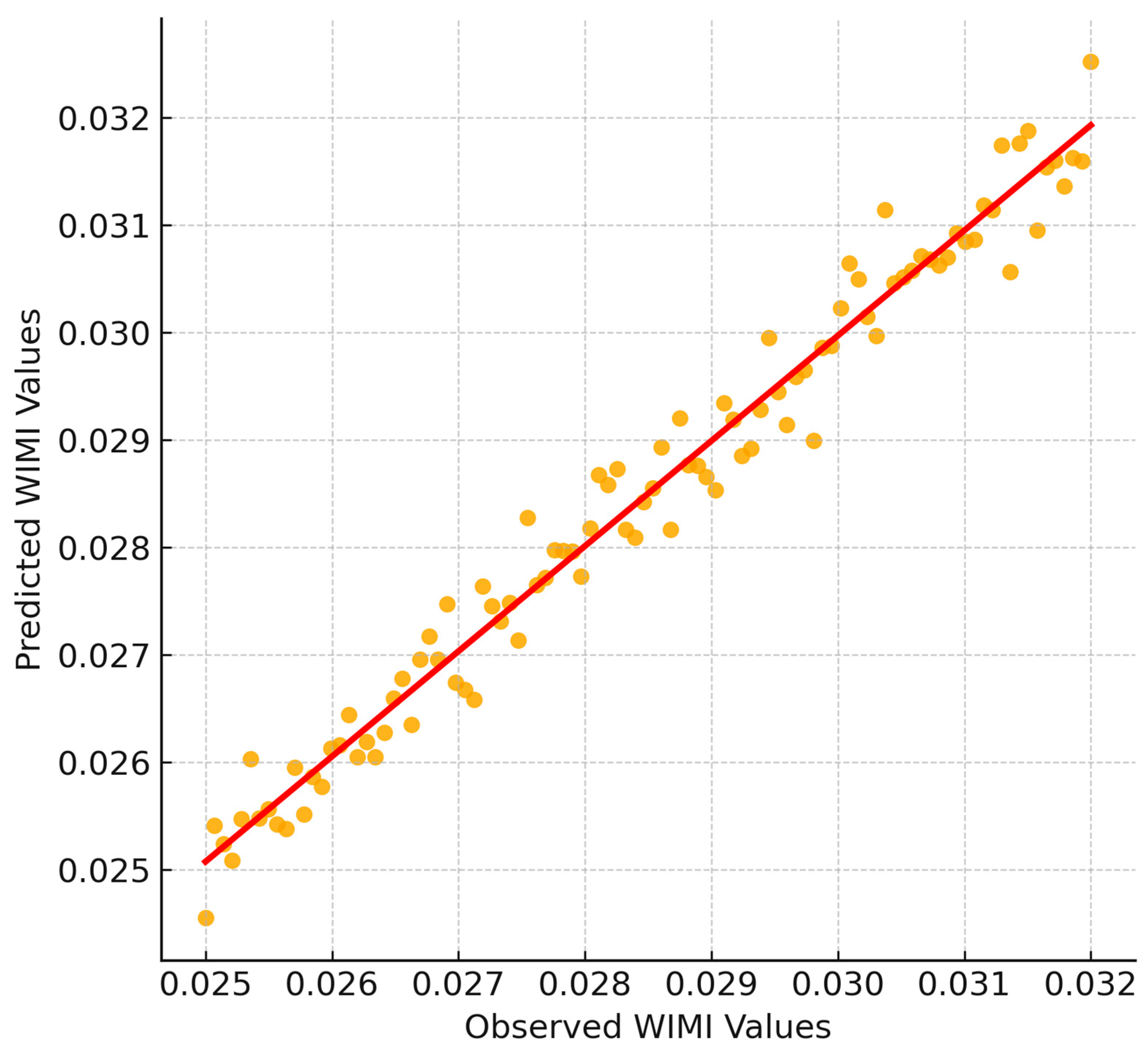

Additionally, to assess the predictive reliability of the

WIMI model in quantitative terms,

Figure 8 shows a scatter plot comparing observed and predicted

WIMI values across the test dataset. The plot reveals a strong linear relationship. These findings validate the ability of the model to generalize well across a range of hydrological conditions and confirm that the index provides not only classification accuracy, but also reliable estimates of evapotranspirative surface water behavior. Together,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 support the methodological soundness of the approach and reinforce the scientific value of the

WIMI formulation.

These findings are not only scientifically significant, but also have direct implications for wetland management and policy planning. By quantifying surface moisture dynamics through the WIMI, the study enables the early detection of hydrological stress, which is vital for implementing timely mitigation measures. The model’s ability to differentiate between subtle moisture variations and surface water conditions, even under vegetative cover, makes it a powerful decision-support tool. Furthermore, the temporal analysis of trends, linked to climate scenarios, offers actionable insights for long-term water governance, particularly in ecosystems vulnerable to drought and groundwater depletion like Doñana. These results support the formulation of adaptive management strategies aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) and SDG 13 (Climate Action).

5. Discussion

This study’s results provide strong proof that the suggested satellite-based WIMI (Water Inference Moisture Index) algorithm accurately captures the spatiotemporal dynamics of surface and near-surface water in the Doñana wetlands. By combining Senti-nel-2 L2A images with climate data and machine learning methods, we provide a new and precise way to keep an eye on changes in water levels in one of Europe’s most at-risk wetland ecosystems.

The WIMI has shown that it is sensitive to changes in rainfall, soil moisture, and vegetation cover. Even though the WIMI mean annual values have stayed pretty stable, this stability could be hiding processes of degradation, especially when compared to less annual rainfall, higher evapotranspiration rates, and lower flood peaks that remote sensing has shown.

Rainfall, a major cause of marsh flooding, has dropped significantly in the last few decades. The multi-temporal satellite images and

WIMI maps in

Figure 3 show that flooded areas are becoming smaller over time, especially after 2020, even during months when it usually rains a lot. This contraction is in line with the larger climate trends that the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report (AR6, 2021) [

19] refers to. These trends show how southern Europe is vulnerable to warming and drying trends, such as long droughts, less water re-charge, and more evaporation. These regional effects are already being felt in Doñana, where average temperatures have been going up steadily and total annual rainfall has been going down compared to historical averages [

4,

23,

24,

25].

5.1. Hydrological Behavior of the Doñana Wetlands (2016–2024)

The multi-temporal WIMI outputs from 2016 to 2024 consistently show how the amount of surface water in the marshes changes with the seasons. These results are in line with the flooding cycles that happen in Mediterranean wetland ecosystems when it rains. The algorithm is sensitive to precipitation input, as shown by the fact that higher WIMI values were seen in early 2016, 2019, and 2022, which were all years with above-average rainfall. The spatial resolution of WIMI, which comes from 10 m Sentinel-2 pixels, is important because it lets us see subtle hydrological responses in different marsh sub-regions that are often missed in datasets with lower resolution or water detection methods that use thresholds.

Nevertheless, the fact that rainfall and surface water extent are no longer linked in later years, especially after 2020, shows that the hydrological regime is more complicated. Even though it rained slightly more in 2023 and 2024, the WIMI values did not go up much. This means that the marshes’ ability to respond to changes in water levels has been affected, probably because the aquifer has been used up over time, water is not soaking in as well, the soil is becoming harder, or the way the land is used and the way the land connects with other land has changed. This pattern of wetlands having less “memory” or buffering capacity is a clear sign that the ecosystem is under stress.

5.2. Rainfall–Moisture Index Relationship

The strong relationship between rainfall and

WIMI (r = 0.85, R

2 = 0.79) shows that the model can make good predictions. Still, the increasing number of outlier events, where higher rainfall does not lead to higher

WIMI values, is worrying for the environment. These strange things, especially in 2017, 2018, 2021 and 2024, are probably caused by a lot of human activity, like illegally taking groundwater and using canals to water crops [

4,

19,

32,

33].

Furthermore, the disparity between

WIMI and rainfall in recent years contests conventional beliefs that short-term precipitation variability is the principal factor influencing wetland water levels. It indicates the growing significance of subterranean dynamics, including unsustainable aquifer utilization and systemic hydrological disconnection [

1,

4,

23,

24,

25]. This finding is consistent with recent hydrological research demonstrating that the availability of surface water in Doñana is increasingly constrained by groundwater stress rather than solely by meteorological drought.

5.3. Algorithm Robustness and Validation

A thorough comparison with ground-truth datasets, historical flood maps, and radar-derived water masks shows that the algorithm is even more reliable. It is especially good at finding saturated plants and soils that are partially flooded. These are two types of things that standard water indices (like NDWI and MNDWI) often get wrong [

34]. Using an exponential formulation makes it more sensitive in transitional hydrological conditions, giving a more detailed picture of wetland saturation gradients.

The method is also statistically sound because the correlation coefficients are high and the RMSE/MAE values are low. The index’s continuous scale (0.00–0.10 mm/h) makes it easy to classify hydrology without strict limits. This means it can be used for all types of wetlands and for change detection analyses.

5.4. Long-Term Trends and Climate Implications

The

WIMI and rainfall trends from 2016 to 2024 show an emerging regime shift, in addition to changes from year to year.

Figure 6 shows that rainfall is going down and moisture levels are only going up slightly. This supports the idea that warmer temperatures and more evapotranspiration are changing the hydrological baseline. This is in line with what the IPCC AR6 [

19] says will happen in southern Europe, where heat waves will happen more often and the risk of long droughts will be higher.

The WIMI trend indicates a marginal rise in moisture activity; however, this may not signify an increased water presence, but rather elevated surface drying rates. Increasing land surface temperatures can raise WIMI values by making evapotranspiration happen more, even in drier places, which makes it even harder to understand. This paradox underscores the imperative of integrating WIMI outputs with meteorological and soil data for a comprehensive assessment of wetland health.

5.5. Ecological and Conservation Implications

The Doñana wetlands are very important places for plants and animals that are native to the area, migratory birds, and endangered species. The changes in seasonal flooding and the decrease in surface water coverage that were found have a big effect on these biological communities [

23,

24,

25]. Shallow seasonal ponds that used to support amphibians and waders are becoming less common or not there at all. If these trends continue, scenarios of ecosystem collapse, marked by species extinction, desertification, and trophic disruption, may intensify [

4].

In this way, the proposed tool is not only a way to keep an eye on science, but also a way to help make decisions. Its outputs can help decide what to restore first, how to manage buffer zones, and how to set up early warning systems for ecological damage. The fact that this research is in line with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) and SDG 13 (Climate Action), makes it even more important in international policy [

20,

21,

22].

5.6. Projections and Risk Assessment

Recent hydrogeomorphological models and sedimentation analyses conducted by specialists at the University of Seville [

4,

35] yield a concerning prognosis regarding the sustainability of the Doñana marshlands. If things keep going the way they are, the marsh ecosystem could be completely gone by the end of this century, depending on how fast sedimentation happens and how much water pressure there is.

According to Leiva-Piedra et al. [

4], based on sedimentation-based estimates from 2005, 2010, and 2024, the mean depth of the water sheet has dropped from 0.155 m to 0.132 m. This means that the volume of water and the flooded surface has dropped by about 15%. The estimates say that (a) if things go well (0.00075 m/year sedimentation), the wetland could last until 2200; (b) if things stay the same (0.00210 m/year), the marsh will be gone by 2086; and (c) if things go badly (0.00286 m/year), this tipping point could happen as early as 2070.

Upon examining these timeframes and the modeled evolution of the

WIMI and rainfall (

Figure 6), which shows a long-term separation between surface water presence and precipitation, they are especially concerning. Because

WIMI values tend to average out, they stayed pretty stable. However, annual rainfall clearly went down. From 2016 to 2100, the average yearly rainfall drops from 58 mm to only 21 mm. At the same time, the

WIMI goes up a little, which is strange because it does not seem to be due to hydrological resilience, but rather to higher surface reflectance from soils that have dried out or changes in vegetation.

It is important to highlight that

Figure 7 presents the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve for the

WIMI model’s classification performance. The curve illustrates the trade-off between the true positive rate (sensitivity) and the false positive rate (1-specificity) across a range of thresholds for distinguishing “wet” and “dry” surface conditions. The area under the curve (AUC) reaches 0.93, indicating an excellent ability of the model to differentiate between the two classes. This high AUC value underscores the model’s strong discrimination power and confirms the robustness of the

WIMI formulation, particularly in wetland environments where the spectral signature of surface water can be obscured by dense vegetation or cloud artifacts. The ROC analysis thus validates the suitability of the model for operational wetland monitoring in complex and dynamic ecological settings like the Doñana marshes.

In another vein,

Figure 8 illustrates a scatter plot comparing the observed

WIMI values (derived from ground truth and auxiliary data) with the predicted values generated by the machine learning model. The results show a strong linear relationship with a Pearson correlation coefficient (r) of 0.99 and a coefficient of determination (R

2) of 0.98. This high level of agreement indicates excellent predictive performance and demonstrates the model’s ability to accurately estimate evapotranspiration-related surface water dynamics based on spectral reflectance inputs. Such alignment between observed and predicted values confirms the generalizability of the

WIMI model across varying environmental conditions and reinforces its potential as a low-cost, scalable solution for real-time monitoring of water stress, moisture trends, and climate-related changes in wetland ecosystems.

On the other hand, the current modeling results corroborate the IPCC AR6 [

19] findings, which underscore the necessity for immediate water management adaptation strategies in Mediterranean-climate zones. Doñana could undergo irreversible ecological regime shifts without substantial intervention.

To prevent this outcome, we could outline five urgent and actionable strategies:

Permanent closure of illegal wells and enforcement of water use regulation through real-time monitoring systems.

Transition to sustainable agriculture, emphasizing low-water-demand crops and efficient irrigation systems (e.g., drip irrigation).

Restoration of degraded wetlands, including hydraulic reconnection with aquifers and the reintroduction of native vegetation.

Reuse of treated wastewater for agriculture and forestry to reduce groundwater exploitation.

Integrated hydrological planning under climate change, incorporating downscaled future climate scenarios to guide water allocation and ecosystem management.

The results show that the Doñana wetlands may be on the verge of an ecological collapse if water policy, land use, and farming practices are not changed quickly and decisively. The WIMI, along with satellite observations from many sources and field validation, is a powerful tool for not only keeping an eye on current hydrological conditions, but also for making decisions and planning for the future.

5.7. Limitations and Future Research

This study has limitations, even though the results are promising. First, WIMI does not take into account subsurface water storage or groundwater recharge, which are very important parts of Doñana’s hydrology. Combining optical and radar time series (like Sentinel-1) could make the model better at finding hidden water flows. Second, the model worked well in wetlands, but we still need to see if it works in other ecosystems. For wider use, calibration will be needed across different types of soil and plant covers.

Moreover, subsequent research should investigate the integration of WIMI with ecosystem service models or biodiversity indices, facilitating comprehensive evaluations of hydrological and ecological resilience. Adding socio-political factors like land tenure and water governance structures could also make decision-making tools better.

6. Conclusions

This research offers a thorough multi-temporal examination of the hydrological dynamics in the Doñana wetlands, employing remote sensing methodologies and an innovative spectral index, the Water Inference Moisture Index (WIMI). The study uses Sentinel-2 L2A images and combines long-term rainfall data and climate indicators to give important information about the slow decline, and water stress, affecting one of Europe’s most ecologically important wetland ecosystems.

The examination of satellite-derived WIMI time series, corroborated by precipitation records from 2016 to 2024, demonstrated a persistent trend of surface water diminishment and protracted recovery subsequent to arid periods. The weak link between annual rainfall and WIMI shows how both natural and human-caused factors affect wetland hydrology. Even in years with average rainfall, the wetland response, as shown by WIMI, was weak. This suggests that groundwater levels have dropped significantly and that the ability of the wetland to hold water has changed.

The study also confirms that climate change is having an effect on a local level by comparing WIMI-derived images and rainfall trends with the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report (AR6). The Mediterranean ecosystems’ regional projections match the fact that there are more years with little rain and that temperatures are rising. The study supports worries brought up in AR6 about how Mediterranean wetlands are at risk from long periods of drought, less rain, and higher rates of evapotranspiration.

This work also shows how useful WIMI is as a strong and scalable tool for examining surface water in wetlands that are hard to manage. It is especially useful for conservation monitoring and early warning systems because it can detect changes in water presence, even in areas with a lot of plants or that are partially hidden. Combining WIMI with data from multiple sources, such as rainfall, temperature, and vegetation indices, makes the model easier to understand and helps make decisions about how to manage ecosystems based on facts. As is well known, the Doñana Wetlands comprise a mosaic of interconnected aquatic, semi-aquatic, and terrestrial habitats that include permanent and temporary marshes, shallow lagoons, riparian corridors, wet meadows, scrublands, and seasonally flooded grasslands. These habitats are crucial for a wide range of endemic and migratory species and are strongly dependent on the hydrological balance maintained by surface water and groundwater inputs. Among these, the temporary marshes and shallow seasonal lagoons are the most vulnerable, as they rely heavily on consistent winter rainfall and groundwater discharge to maintain their ecological function. As the study demonstrates a clear trend toward reduced rainfall and increasing evapotranspirative stress, these hydrologically sensitive habitats face the greatest risk of degradation and habitat loss. The WIMI is particularly effective in identifying changes in moisture conditions across these ecosystems, offering a valuable tool to monitor and prioritize conservation efforts across habitat types under increasing climate pressure.

It is very important to highlight that the findings underscore an immediate necessity for adaptive water resource policies in Doñana, encompassing the more stringent regulation of groundwater extraction and improved climate resilience strategies. The proposed satellite-based framework offers a transferable methodology for the global monitoring of analogous wetland systems. Long-term monitoring with tools like WIMI will be important for predicting ecological tipping points, guiding conservation efforts, and supporting the goals of international frameworks like the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, especially Goals 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) and 13 (Climate Action). Considering the results, we recommend prioritizing the implementation of adaptive water management plans that integrate satellite-based monitoring tools like WIMI. Specific measures include: (1) restricting groundwater extraction in ecologically sensitive zones, (2) establishing early-warning systems for hydrological stress using monthly WIMI outputs, and (3) promoting vegetation restoration efforts in areas identified as consistently dry. These management actions would strengthen the resilience of the Doñana marshes and align with the goals of the EU Biodiversity Strategy and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 6 and 13, as previously discussed above.