Water, Food and Ecosystem Nexus in the Coastal Zone of Northeast Pará, Eastern Amazon, Brazil

Abstract

1. Introduction

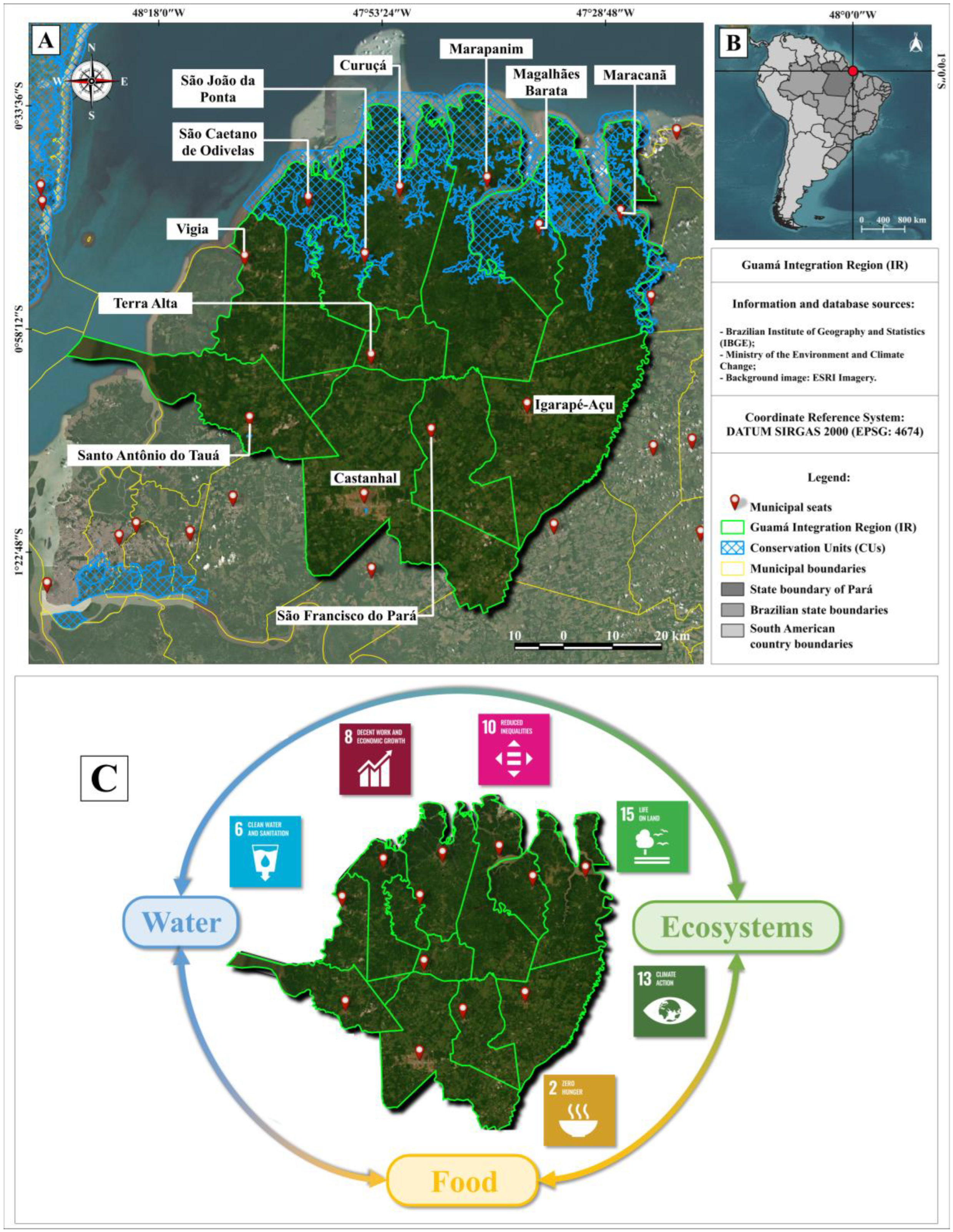

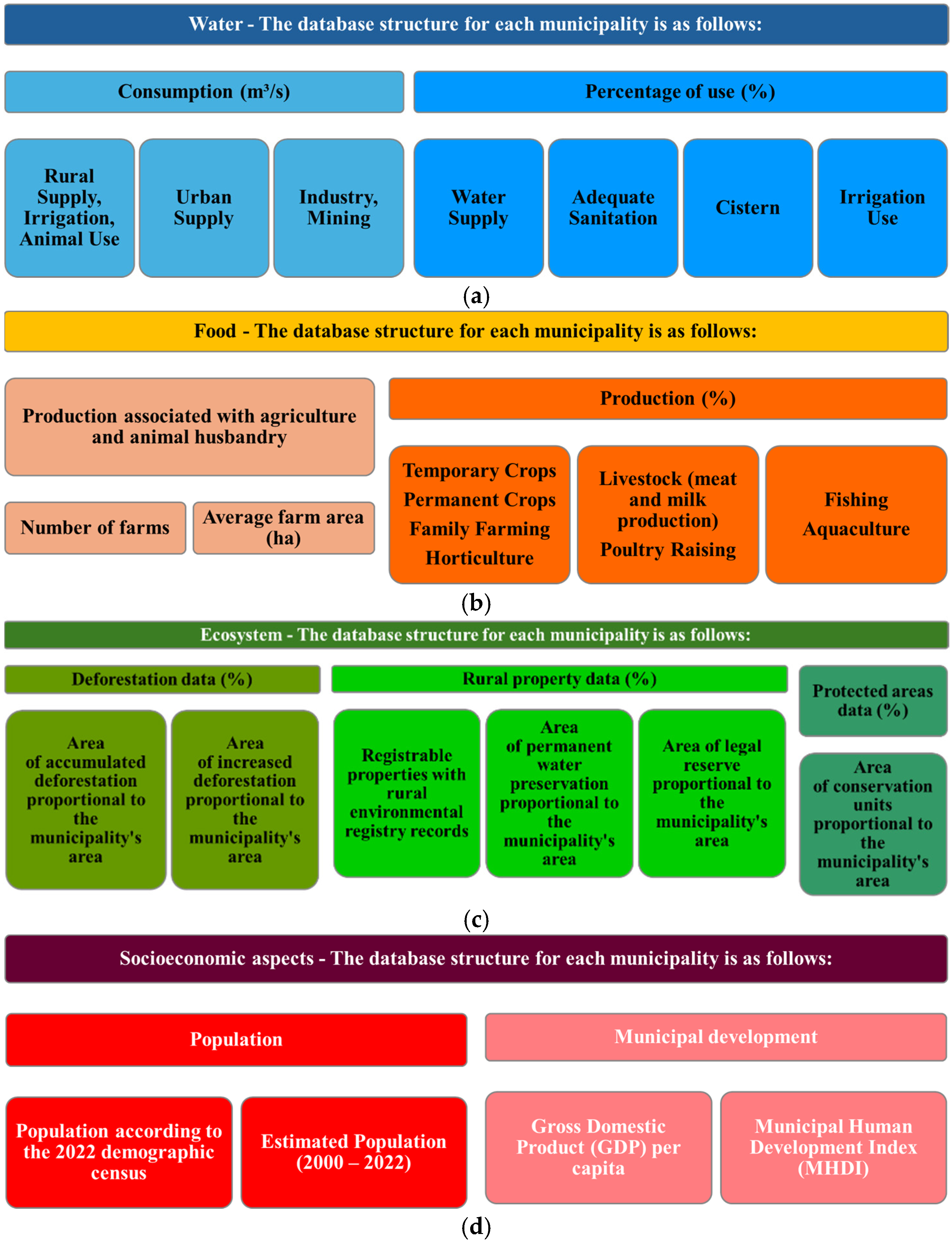

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Water Axis

3.2. Food Axis

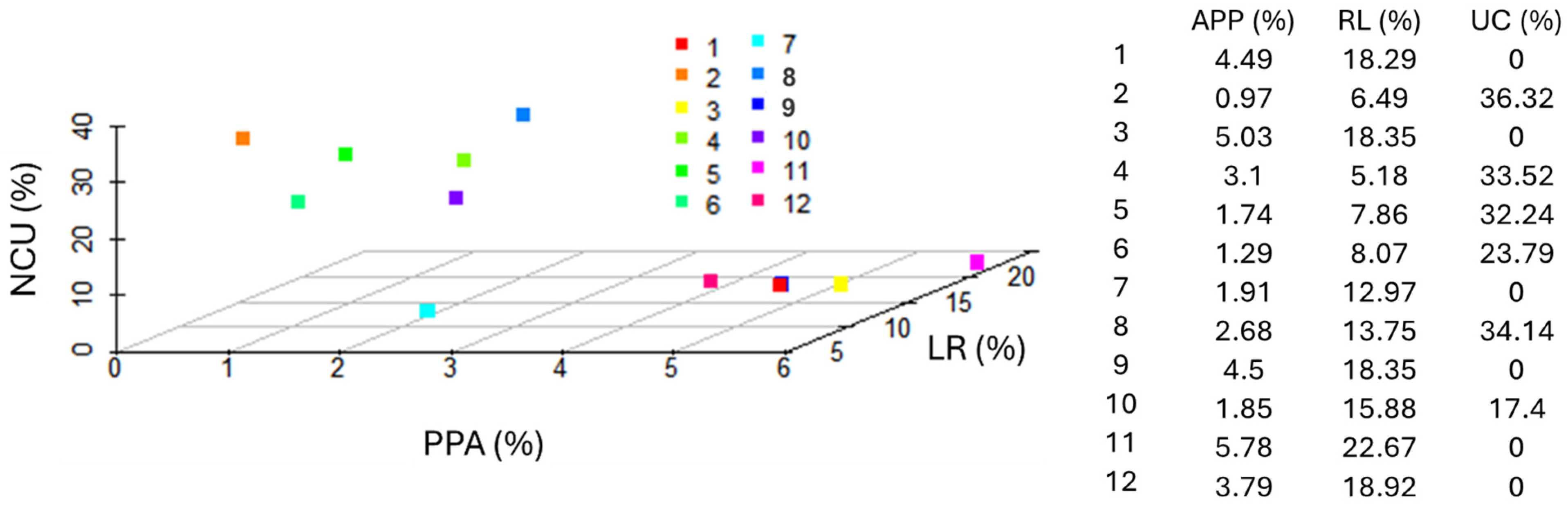

3.3. Ecosystem Axis

4. Discussion

4.1. WFE Nexus Assessment

4.2. WFE Nexus and Environmental Policies

- -

- In order to ensure a healthy relationship between ecosystems and food production, it is necessary to decouple deforestation from agricultural production. Otherwise, insufficient public policy action will result in continued deforestation and the marginalization of vulnerable groups [18].

- -

- The protective function of forests is significant in coastal zones. They control erosion, preserve water recharge areas and provide biomass for energy generation, food production and income generation. They also protect against the effects of droughts and floods and support fauna in highly sensitive environments. Therefore, consolidating the Ecosystem-Water Nexus directly impacts the conservation of coastal systems and tributary river basins [54].

- -

- The nexus approach is not without its critics, as there are limitations to how far it can encompass ecological or environmental processes that transcend the conceptualization of the axes. In the Amazon, the nexus is interconnected with factors involving climate change, land use patterns and the natural resources that sustain people’s livelihoods. Deforestation of the Amazon rainforest represents another threat to water and energy security [55].

- -

- In the coastal zone of the eastern Amazon, significant impacts on riparian habitats include biodiversity loss and the fragmentation of natural vegetation. Traditional communities have had their livelihoods transformed, resulting in economic losses and forcing them to alter their way of life. Therefore, it is necessary to consolidate public policies, regulatory processes, and oversight by responsible agencies, in addition to the continuous monitoring of hydroecological processes [56].

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CU | Conservation Unit |

| RESEX | Extractive Reserves |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| LR | Legal Reserve Area |

| MHDI | Municipal Human Development Index |

| RER | Percentage of Rural Environmental Registry |

| SDGS | Sustainable Development Goals |

| PPA | Water Permanent Preservation Areas |

| WFE | Water-Food-Ecosystem |

References

- Nhamo, L.; Ndlela, B.; Mpandeli, S.; Mabhaudhi, T. The water-energy-food nexus as an adaptation strategy for achieving sustainable livelihoods at a local level. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoleto, A.P.; Franco Barbosa, P.S.; Maniero, M.G.; Guimarães, J.R.; Vieira Junior, L.C.M. A Water-energy nexus analysis to a sustainable transition path for Sao Paulo State, Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 319, 128697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q. Interlinking climate change with water-energy-food nexus and related ecosystem processes in California case studies. Ecol. Process. 2016, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagata, Y.; Hanasaki, N.; Ito, A.; Kinoshita, T.; Murakami, D.; Zhou, Q. Estimating water–food–ecosystem trade-offs for the global negative emission scenario (IPCC-RCP2. 6). Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Xu, Y.J.; Hu, B.; Sun, J.; Yu, Y.; Guo, Y. Optimizing the balance among water use, food production, and ecosystem integrity at the regional scale. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 317, 109670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.S. Health is the landing zone for climate change adaptation. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2025, 9, 829–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Han, X.; Ma, B.; Li, D.; Wang, Z.; Hao, Z.; Zhang, X. Research on the Coupling Coordination Relationship and Spatial Equilibrium Measurement of the Water–Energy–Food Nexus System in China. Water 2025, 17, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Liu, W.; Sun, Y. Comparative Study of Water–Energy–Food–Ecology Coupling Coordination in Urban Agglomerations with Different Development Gradients. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohtar, R.; Peng, J.; Daher, B.; He, X. Challenges and future actions on water-economy-ecology-society nexus under changing environment. River 2024, 3, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zuo, Q.; Wu, Q.; Han, C.; Tao, J. An integrated diagnostic framework for water resource spatial equilibrium considering water-economy-ecology nexus. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 414, 137592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, A.; Yamada, M.; Miyashita, Y.; Sugimoto, R.; Ishii, A.; Nishijima, J.; Fujii, M.; Kato, T.; Hamamoto, H.; Kimura, M.; et al. Dynamics of water–energy–food nexus methodology, methods, and tools. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2020, 13, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, N.; Avellán, T.; Teutschbein, C.; Blicharska, M. Towards a common understanding of water-energy-food nexus research: A view of the European nexus community and beyond. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 967, 178775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, L.M.; Ometto, J.P.; Arcoverde, G.F.; Branco, E.A.; Toledo, P. Water-Energy-Food Nexus Under Climate Change: Analyzing Different Regional Socio-ecological Contexts in Brazil. In Water-Energy-Food Nexus and Climate Change in Cities; Lazaro, L.L.B., Giatti, L.L., Valente de Macedo, L.S., Puppim de Oliveira, J.A., Eds.; Sustainable Development Goals Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, F.A.; Dalla Fontana, M.; Malheiros, T.F.; Di Giulio, G.M. The Water-Energy-Food Nexus: What the Brazilian Research has to Say; USP School of Public Health: São Paulo, Brazil, 2022; 291p. [Google Scholar]

- Von Sperling, E. Hydropower in Brazil: Overview of positive and negative environmental aspects. Energy Procedia 2012, 18, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcoverde, G.F.B.; Menezes, J.A.; Paz, M.G.A.; Barros, J.D.; Guidolini, J.F.; Branco, E.A.; Andrade, P.R.; Pulice, S.M.P.; Ometto, J.P.H.B. Sustainability assessment of Cerrado and Caatinga biomes in Brazil: A proposal for collaborative index construction in the context of the 2030 Agenda and the Water-Energy-Food Nexus. Front. Phys. 2023, 10, 1060182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, E.A.; Araújo, I.F.; Feltran-Barbieri, R.; Perobelli, F.S.; Rocha, A.; Sass, K.S.; Nobre, C.A. Economic drivers of deforestation in the Brazilian Legal Amazon. Nat. Sustain. 2024, 7, 1141–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milhorance, C.; Bursztyn, M. Climate adaptation and policy conflicts in the Brazilian Amazon: Prospects for a Nexus+ approach. Clim. Chang. 2019, 155, 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansur, A.V.; Brondízio, E.S.; Roy, S.; Hetrick, S.; Vogt, N.D.; Newton, A. An assessment of urban vulnerability in the Amazon Delta and Estuary: A multi-criterion index of flood exposure, socio-economic conditions and infrastructure. Sustain. Sci. 2016, 11, 625–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza-Filho, P.W.M.; Lessa, G.C.; Cohen, M.C.L.; Costa, F.R.; Lara, R.J. The Subsiding Macrotidal Barrier Estuarine System of the Eastern Amazon Coast, Northern Brazil. In Geology and Geomorphology of Holocene Coastal Barriers of Brazil; Lecture Notes in Earth Sciences; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timko, J.; Le Billon, P.; Zerriffi, H.; Honey-Rosés, J.; La Roche, I.; Gaston, C.; Sunderland, T.; Kozak, R.A. A policy nexus approach to forests and the SDGs: Tradeoffs and synergies. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 34, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, A.S.; Mosnier, A.; Havlík, P.; Valin, H.; Herrero, M.; Schmid, E.; O’Hare, M.; Obersteiner, M. Cattle ranching intensification in Brazil can reduce global greenhouse gas emissions by sparing land from deforestation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 7236–7241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, R.K.; Osbeck, M.; Dawkins, E.; Tuhkanen, H.; Nguyen, H.; Nugroho, A.; Gardner, T.A.; Wolvekamp, P. Hybrid governance in agricultural commodity chains: Insights from implementation of ‘No Deforestation, No Peat, No Exploitation’ (NDPE) policies in the oil palm industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 183, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, Y.A.D.S.; Lima, A.M.M.D.; Silva, C.M.S.E.; Franco, V.D.S.; Raiol, L.L.; Oliveira, I.S.D.; Dias, M.L.N.; Beltrão Júnior, P.R.E. Hydro-meteorological dynamics of rainfall erosivity risk in the Amazon River Delta-Estuary. J. Water Clim. Chang. 2025, 16, 1673–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, W.L.D.; Rocha, G.D.M.; Flores, M.D.S.A.; Ribeiro, É.R.F.; Tamasauskas, C.E.P.; Gass, S.L.B. Zoneamento geoambiental a partir das unidades de conservação: Subsídios para a gestão integrada da zona costeira paraense-Brasil. Rev. Bras. De Geogr. Física 2020, 13, 3042–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristiano, E.; Deidda, R.; Viola, F. The role of green roofs in urban water-energy-food-ecosystem nexus: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 756, 143876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asuero, A.G.; Sayago, A.; González, A.G. The Correlation Coefficient: An Overview. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2006, 36, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlet, L.; Barboza, R.S.L.; Van Putten, I.E.; Akpan, A.; Siriwardane-de Zoysa, R.; Glaser, M. Perceptions of governance and access in artisanal marine fisheries in northern Brazil. Ecol. Soc. 2025, 30, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, G.; Glaser, M. Co-evolving geomorphical and socio-economic dynamics in a coastal fishing village of the Bragança region (Pará, North Brazil). Ocean Coast. Manag. 2003, 46, 859–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanure, T.M.P.; Miyajima, D.N.; Magalhães, A.S.; Domingues, E.P.; Carvalho, T.S. The impacts of climate change on agricultural production, land use and economy of the legal amazon region between 2030 and 2049. Economia 2020, 21, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gama-Rodrigues, A.C.; Müller, M.W.; Gama-Rodrigues, E.F.; Mendes, F.A.T. Cacao-based agroforestry systems in the Atlantic Forest and Amazon Biomes: An ecoregional analysis of land use. Agric. Syst. 2021, 194, 103270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, V.A.B.; Vancine, M.H.; Lima, A.M.M.; Toledo, P.M. Dinâmica da paisagem e fragmentação de ecossistemas em três bacias hidrográficas na Amazônia Oriental entre 1985 e 2019. Rev. Bras. De Geogr. Física 2023, 16, 936–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, F.A.; Assad, E.D.; Bebbington, D.H.; Brondizio, E.S.; Fearnside, P.M.; Garrett, R.; Hecht, S.; Heilpern, S.; Mcgrath, D.; Oliveira, G.; et al. Complex, diverse and changing agribusiness and livelihood systems in the Amazon. Acta Amaz. 2024, 54, e54es22096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, M.D.M.R.; Sousa, L.M.; Ribas, G.G. Sustainable Production Systems in the Brazilian Amazon: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanches Ferreira, N.; Meiguins de Lima, A.M.; Cardoso Gomes, D.J. Vulnerabilidade das áreas úmidas e influência sazonal da precipitação pluviométrica na Amazônia Oriental. GEOFRONTER 2023, 9, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahum, J.S.; Santos, L.S.; Santos, C.B. Formação da dendeicultura na Amazônia paraense. Mercator 2020, 19, e19007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, J.R.B.; Silva Leite, T.V.; Silva, E.L.S.; Santos, J.F. Análise espacial das unidades de paisagem da Reserva Extrativista Marinha Mocapajuba, zona costeira do Nordeste Paraense. Rev. Cerrados 2018, 16, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passos, P.H.S.; Coelho, M.C.M.; Ribeiro, S.C.A.; Coelho, J.L.; Almeida, M.C.; Vergara Filho, W.L. Manejo do Caranguejo-Uçá: O Método de Embalagem Para o Transporte Sustentável; IDSM: Belém, Brazil, 2020; 60p. [Google Scholar]

- Simard, M.; Fatoyinbo, L.; Smetanka, C.; Rivera-Monroy, V.H.; Castañeda-Moya, E.; Thomas, N.; Van der Stocken, T. Mangrove canopy height globally related to precipitation, temperature and cyclone frequency. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, K.; Randhir, T.O.; Valente, R.A.; Vettorazzi, C.A. Riparian restoration for protecting water quality in tropical agricultural watersheds. Ecol. Eng. 2017, 108, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogeboom, R.J.; Borsje, B.W.; Deribe, M.M.; Van Der Meer, F.D.; Mehvar, S.; Meyer, M.A.; Özerol, G.; Hoekstra, A.Y.; Nelson, A.D. Resilience Meets the Water–Energy–Food Nexus: Mapping the research landscape. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 630395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardozo, E.G.; Celentano, D.; Rousseau, G.X.; Silva, H.R.E.; Muchavisoy, H.M.; Gehring, C. Agroforestry systems recover tree carbon stock faster than natural succession in Eastern Amazon, Brazil. Agrofor. Syst. 2022, 96, 941–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, F.E.D.; Santos Oliveira, J.D.N.; Santos, C.R.C.; Oliveira Ferreira, E.V.; Silva, R.T.L.; Paula, M.T.; Alves, J.D.N.; Oliveira, J.S.R.; Rodrigues, J.I.M.; Martins, W.B.R. Physical and chemical soil quality and litter stock in agroforestry systems in the Eastern Amazonia. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 382, 109479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filgueiras, T.C.G.M.; Jacob, V.; Miranda, C.D.S.C.; Gonçalves, N.V.; Conceição Santos, A.; Nahum, J.S. As trabalhadoras do dendê: Uma análise sobre o trabalho da mulher na cadeia produtiva do dendê. Rev. Caribeña De Cienc. Soc. 2024, 13, e3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homma, A. A terceira natureza da Amazônia. Rev. Parana. De Desenvolv. 2017, 38, 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Homma, A.K.O.; Menezes, A.J.E.A.; Santana, C.A.M.; Navarro, Z. The more sustainable development of the Amazon region: Between (many) controversies and the possible path. COLÓQUIO—Rev. Do Desenvolv. Reg. 2020, 17, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, P.A.; Passos, M.M. Características e distribuição das formações de Mauritia flexuosa L. F. na microrregião do salgado paraense. In A Geografia do Pará em Múltiplas Perspectivas: Natureza, Urbano, Rural e Cultura, 1st ed.; Hespanhol, R.A.M., Melazzo, E.S., Eds.; Editora ANAP: Tupã, Brazil, 2017; pp. 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, R.J.M.; Gonçalves, W.G.; Gonçalves, J.P.; Nunes, G.D.L.; Silva, E.R.M.; Maia, J.S.; Adami, M.; Narvaes, I.S. Análise do uso e ocupação do solo em Marapanim-PA a partir de dados do projeto TerraClass. Holos 2018, 1, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Siqueira-Gay, J.; Yanai, A.M.; Lessmann, J.; Pessôa, A.C.M.; Borja, D.; Canova, M.; Borges, R.C. Pathways to positive scenarios for the Amazon forest in Pará state, Brazil. Biota Neotrop. 2020, 20, e20190905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhave, A.G.; Conway, D.; Dessai, S.; Stainforth, D.A. Water resource planning under future climate and socioeconomic uncertainty in the Cauvery River Basin in Karnataka, India. Water Resour. Res. 2018, 54, 708–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yung, L.; Louder, E.; Gallagher, L.A.; Jones, K.; Wyborn, C. How methods for navigating uncertainty connect science and policy at the water-energy-food nexus. Front. Environ. Sci. 2019, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, H.; Smith, T.F.; Rangel-Buitrago, N. Analyzing the impact and evolution of ocean & coastal management: 30 years in retrospect. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2023, 242, 106697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Ramírez, C.J.; Chávez, V.; Silva, R.; Muñoz-Perez, J.J.; Rivera-Arriaga, E. Coastal management: A review of key elements for vulnerability assessment. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimaraes, M.M.; Pedrozo, E.A. Nexo água-energia-alimentos e floresta: Integração necessária. Rev. De Adm. E Negócios Da Amaz. 2021, 13, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzuti, C.B.; Zuanon, J.; Ribas, C.; Wittmann, F.; d’Horta, F.; Sawakuchi, A.O.; Lopes, P.F.M.; Carneiro, C.C.; Akama, A.; Garzón, B.R.; et al. Belo Monte through the Food-Water-Energy Nexus: The disruption of a unique socioecological system on the Xingu River. In The Water-Energy-Food Nexus: What the Brazilian Research has to Say; Chapter 1; Moreira, F.A., Dalla Fontana, M., Malheiros, T.F., Di Giulio, G.M., Eds.; USP School of Public Health: São Paulo, Brazil, 2022; pp. 22–40. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, R.M.; Paranhos Filho, A.C.; Sieber, S. A novel Water-Food-Energy nexus approach integrating Analytic Hierarchy Process and Google Earth Engine using global datasets for photovoltaic energy generation. Renew. Energy Focus 2022, 43, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieber, N.; Ker, J.H.; Wang, X.; Triantafyllidis, C.; van Dam, K.H.; Koppelaar, R.H.; Shah, N. Sustainable planning of the energy-water-food nexus using decision making tools. Energy Policy 2018, 113, 584–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Axes Nexus | SDGs | Data | Sources | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water |  | Consumptive uses of water | ANA 1 | 2022 |

| Water supply | SNIS 2 | 2020 | ||

| Adequate sewage system | IBGE 3 | 2010 | ||

| Cistern on rural properties | IBGE | 2017 | ||

| Irrigation | IBGE | 2017 | ||

| Food |  | Permanent crop production | IBGE, FAPESPA 4 | 2017 e 2019 |

| Temporary crop production | IBGE, FAPESPA | 2017 e 2019 | ||

| Livestock production | IBGE, FAPESPA | 2017 e 2019 | ||

| Aquaculture production | SEDAP 5 | 2019 | ||

| Degraded pastures | MapBiomas | 2020 | ||

| Ecosystem |   | Accumulated Deforestation | INPE 6 | 1988–2007 |

| Annual Deforestation Increase | INPE | 2008–2021 | ||

| Percentage of Rural Environmental Registry (RER) (*) | SICAR 7–SEMAS 8 | 2022 | ||

| Water Permanent Preservation Areas (PPA) | SICAR–SEMAS | 2022 | ||

| Legal Reserve Area (LR) (**) | SICAR–SEMAS | 2022 | ||

| Conservation Unit Area (CUA) | IDEFLOR-BIO 9 e ICMBIO 10 | 2022 | ||

| Socioeconomic aspects |   | Estimated Population | IBGE | 2000 e 2022 |

| Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita | IBGE | 2019 | ||

| Municipal Human Development Index (MHDI) | PNUD 11 | 2010–2020 |

| r | Description |

|---|---|

| 0.95 | As the region has undergone historical anthropization, native vegetation has been almost completely suppressed, giving way mainly to pastureland. |

| 0.90 | The increase in rural property registrations in the RER reveals rural properties with land use focused on livestock activities. |

| 0.87 | As the region has undergone historical anthropization, native vegetation has been almost completely suppressed, giving way mainly to pastureland. |

| 0.83 | The LR area is a proxy variable for RER, explaining the positive correlation with livestock activity. |

| 0.81 | The water PPA is a proxy variable for RER, explaining the positive correlation with livestock activity. |

| 0.74 | The increase in rural property registrations in the RER reveals rural properties with land use focused on livestock activities. |

| 0.70 | The water PPA is a proxy variable for RER, explaining the positive correlation with livestock activity. |

| 0.66 | The LR area is a proxy variable for RER, explaining the positive correlation with livestock activity. |

| 0.64 | |

| 0.60 | The LR area is a proxy variable for RER, explaining the positive correlation with permanent crop activity. |

| 0.59 | The increase in rural property registrations in the RER reveals rural properties with land use focused on livestock activities. |

| −0.83 | As they are mutually exclusive classes, the absence of NCU implies the proliferation of pasture in the anthropized region. |

| −0.70 |

| Municipality | Agricultural Establishments | Temporary Crops (%) | Permanent Crops (%) | Livestock (%) | Fishing and Aquaculture (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | Average Area (ha) | |||||

| Castanhal | 10.80 | 34.10 | 51.12 | 22.47 | 14.06 | 0.81 |

| Curuçá | 5.48 | 12.80 | 43.74 | 31.75 | 4.76 | 1.06 |

| Igarapé-Açu | 20.55 | 22.98 | 63.22 | 21.21 | 7.15 | 0.8 |

| Magalhães Barata | 4.26 | 26.49 | 83.45 | 6.35 | 2.27 | 2.95 |

| Maracanã | 16.98 | 10.95 | 71.98 | 9.91 | 4.67 | 3.53 |

| Marapanim | 8.81 | 13.53 | 78.27 | 9.66 | 3.62 | 0.22 |

| Santo Antônio do Tauá | 8.54 | 21.80 | 39.98 | 26.05 | 6.68 | 0.23 |

| São Caetano de Odivelas | 6.05 | 23.13 | 50.96 | 18.69 | 11.82 | 1.6 |

| São Francisco do Pará | 6.63 | 51.72 | 56.85 | 21.72 | 11.08 | 0 |

| São João da Ponta | 1.75 | 38.44 | 77.35 | 13.26 | 4.97 | 0 |

| Terra Alta | 1.01 | 20.30 | 53.85 | 37.50 | 6.73 | 0 |

| Vigia | 9.14 | 8.73 | 35.56 | 33.23 | 12.59 | 0.32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dutra, V.A.B.; Lima, A.M.M.d.; Toledo, P.M.d.; Rocha, Y.A.d.S. Water, Food and Ecosystem Nexus in the Coastal Zone of Northeast Pará, Eastern Amazon, Brazil. Geographies 2025, 5, 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies5040073

Dutra VAB, Lima AMMd, Toledo PMd, Rocha YAdS. Water, Food and Ecosystem Nexus in the Coastal Zone of Northeast Pará, Eastern Amazon, Brazil. Geographies. 2025; 5(4):73. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies5040073

Chicago/Turabian StyleDutra, Vitor Abner Borges, Aline Maria Meiguins de Lima, Peter Man de Toledo, and Yuri Antonio da Silva Rocha. 2025. "Water, Food and Ecosystem Nexus in the Coastal Zone of Northeast Pará, Eastern Amazon, Brazil" Geographies 5, no. 4: 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies5040073

APA StyleDutra, V. A. B., Lima, A. M. M. d., Toledo, P. M. d., & Rocha, Y. A. d. S. (2025). Water, Food and Ecosystem Nexus in the Coastal Zone of Northeast Pará, Eastern Amazon, Brazil. Geographies, 5(4), 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies5040073