Transracial Adoption Among Asian Youth: Transitioning Through an Integrative Identity

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background: Transracial Adoption Involving Asian Children

1.2. Study Rationale: TRA Considerations

1.3. The Impact of TRA on Mental Health

1.4. “Youth in Transition” Framework

2. Method

2.1. Survey Design

2.2. Interviews

2.3. Ethical Issues

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Survey Findings

3.3. Interview Findings

3.4. Integrative Findings

4. Discussions

4.1. Factor 1: Asian Youth’s Participation and Appreciation

4.2. Factor 2: TRA Best Practices

4.3. Recommendations for Parents

4.4. Social and Racial Justice

5. Limitations

6. Future Research Recommendations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Parents (n = 14) | Adoptees (n = 7) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Response | Mean (SD) | Response | Mean (SD) |

| Age | 59.57 (7.13) | Age | 24.00 (1.63) |

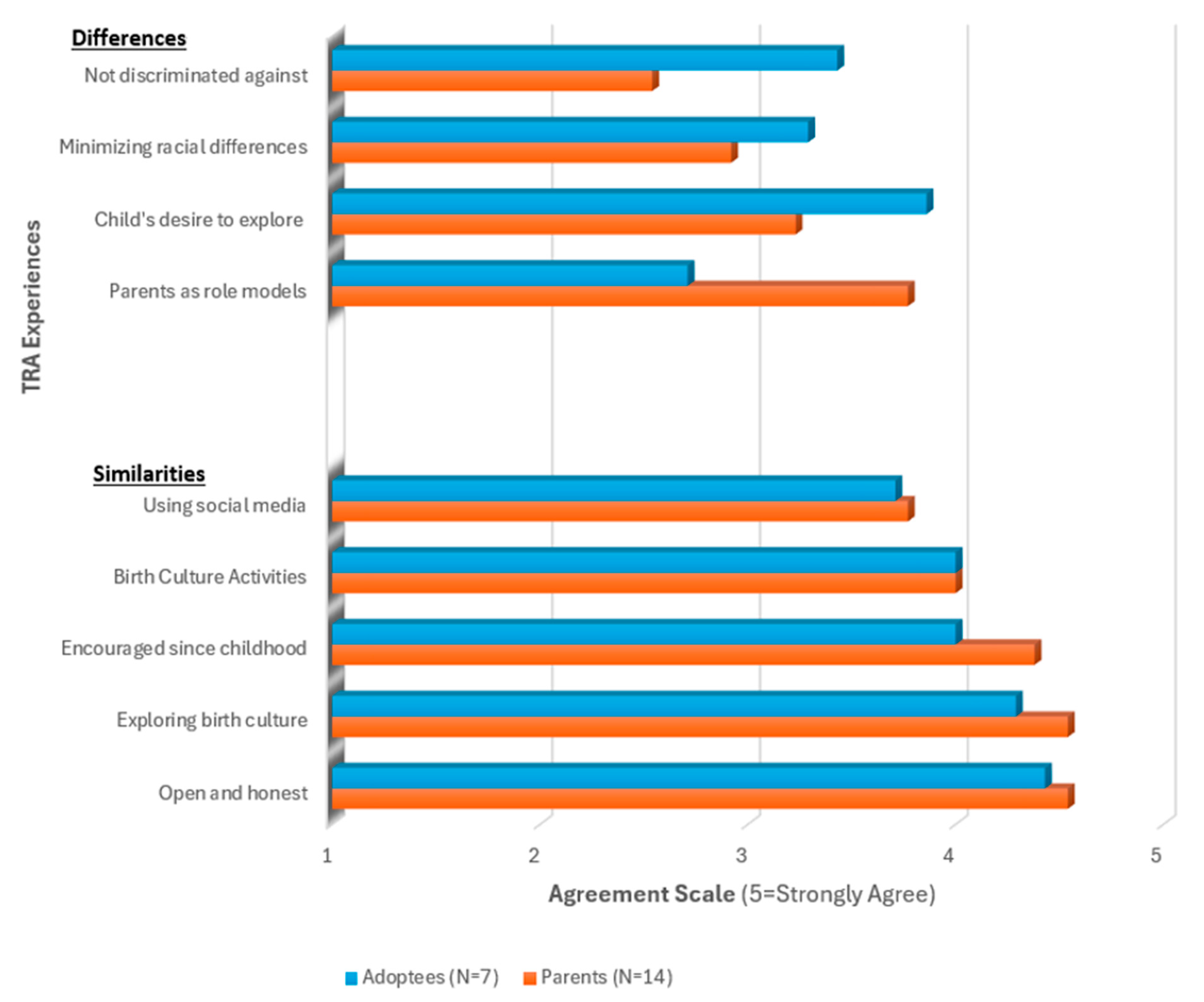

| Similarities between Adoptive Parents and Adoptees: | |||

| It is important to have open and honest conversations surrounding race and adoption. | 4.54 (1.13) | My parent(s) felt comfortable discussing adoption with me. | 4.43 (0.79) |

| I am comfortable when my child explores the birth culture of their racial group. | 4.54 (1.20) | Now that I am older, I am comfortable with being adopted. | 4.29 (0.76) |

| When my child was younger, I was the one who first encouraged my child to explore their racial/ethnic identity. | 4.38 (0.65) | I felt that my parents encouraged my curiosity about my racial identity when I was growing up. | 4.00 (1.41) |

| I encouraged my child to participate in activities or organizations for their racial group. | 4.00 (0.82) | My parents encouraged me to participate in various cultural activities such as heritage tours, learning my birth language, or eating meals of my birth culture. | 4.00 (1.53) |

| Social media helped me connect with other adoptive parents and explore more information about my child’s racial identity. | 3.77 (1.30) | Social media helped me connect with other adoptees, learn about their experiences with adoption, and explore my racial identity. | 3.71 (1.25) |

| Differences between Adoptive Parents and Adoptees: | |||

| I encouraged my child to find role models who looked like them. | 3.77 (1.01) | I had a role model who looked like me. | 2.71 (1.38) |

| My child’s desire/interest to explore their racial identity decreased as they became older. | 3.23 * (1.17) | I have become more curious about exploring my racial identity compared to when I was younger. | 3.86 * (0.90) |

| Even though my child is of a different race, I attempt to minimize my child’s racial differences. | 2.92 * (1.38) | I was exposed to different people who looked like me during my childhood. | 3.29 * (1.70) |

| I believe my child has never been discriminated against based on the color of their skin. | 2.54 * (1.39) | My parent(s) felt comfortable discussing issues of race, such as discrimination, microaggressions, and racism. | 3.43 * (1.27) |

| Questions only for Parents: | Questions only for Adoptees: | ||

| I believe my child can fit in with others who are of the same racial background as they are. | 3.62 (0.65) | ||

| In the US, I believe we live in a colorblind society where race does not matter. | 1.77 (0.60) | ||

| I was told from a young age that I was adopted. | 5.00 (0.00) | ||

| I desired to look for/search for my birth parents if I did not know them. If I knew them, I would want to know them better. | 3.71 (0.95) | ||

| I could join adoption support groups or attend adoption-related events to meet other adoptees. | 3.57 (1.27) | ||

| I was able to create my own adoption story growing up freely. | 3.43 (0.98) | ||

| I was the only person whom my immediate family adopted. | 1.43 (0.79) | ||

| Theme | Quotes Parents (P1 to P7) and Adoptees (A1 to A4) |

|---|---|

| Support formation | P1: My daughter was around adopted children and thought it was perfectly normal to be adopted from China because she saw plenty of other examples and wasn’t the only one. P2: We met many people with similar family makeup, so [my daughter] didn’t feel so alone. P5: Have a support system before they even bring their child home. Adoption can be hard enough on all parties as it is. P6: They have immersive or bilingual education, [finding] cultural role models for their kids, [and] incorporating some of their [birth] customs with traditions the family already has. P7: Those events were helpful to them and seeing their identity. But I think hanging out with [their] friends [was] more helpful for them [to create] their racial identity. A1: Yeah, I don’t think I had a personal role model in my life. A2: Nothing that can come from the top of my head. A4: My exchange student. She definitely had an influence on me because she was Asian. |

| Differences in cultural expectations | P3: As a parent, I can be reduced to tears right now with the joy she brings us. I’m always aware that to put [my child] in a situation where she sees her culture in a positive way by thinking of [me as] a role model and saying, Look [as I told my child], this is another person of your culture. P5: There were a lot of unknowns and questions about why this happened. [My child asked] Why [did my birth parents] give me up? Why do they do this or that? Things we can’t answer. I think it’s a lot more historical, unanswered questions, kind of trauma. P6: I think love makes up for a lot, too. Just consistency, love, and letting them know that whatever they don’t get right now, they can get later. A1: I remember feeling uncomfortable at it, like I always felt uncomfortable that my White parents and their White parents were doing a Chinese New Year because I didn’t feel like it was our culture. A3: I felt like a little bit guilt or like a weird feeling that wasn’t [my adoptive mom]. So it made me feel weird. My adopted mom wasn’t part of the group that I felt like I belonged to. A4: My parents have been very open with [my sister and me] about letting us know where we’ve come from and helping us with our emotions. Letting us talk about it if we need to, and they don’t try to push it; they leave the door open if we want to, which has definitely helped. |

| Differences between siblings | P4: [One daugher] strongly identified as American, whereas [my other daughter] would like to spend time in China and maybe even settle there. P5: [My youngest daughter] got into being Chinese, but the older one never did. P7: They are night and day. A1: She’s very different from me and has never been as curious or interested in her Asian American identity as I have. A4: [My sister and I] are definitely opposites when it comes to our identity and history and whether or not we want to talk about it. I was very into talking about it with my mom. |

| Shifts in identity | P1: My daughter says that she is American. She does not identify that much with being Chinese. I mean, she knows her race is Chinese, but she feels she is American. P4: My youngest daughter found it confusing to look like one thing and be another thing in her heart, [since] White people saw her as Chinese when she felt White, and Chinese people saw her as Chinese when she felt White. A1: I didn’t care about it so much when I was young, and then when I was older, I wanted to have more of an Asian identity. A2: It never occurred to me that I wasn’t Asian because we attended many Chinese New Year festivals, and they tried to incorporate that background into our growing up. And so I never felt disconnected from it in a sense. A3: I know that it gets confusing, and it’s something I don’t really think about a lot…I sometimes feel embarrassed to say that I’m Hispanic because I know I’m not. I don’t feel like I am in other situations. I feel more confident. A4: When I was younger, I was interested in my story and past. Since I’ve gotten older, I’ve definitely shied away from it. Even at one point, a couple of years ago, I was really into it again, and then I went back to it. I’m not that interested. |

| Resource | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-Racism Toolkit | A resource created explicitly for adoptive parents and families to learn about race and racial identity development within the context of transracial adoption. | [63] |

| Child Trauma Academy Library | A database of research, interventions, and information on child trauma. | [64] |

| Cultural Humility Toolkit | A webpage of resources, tools, and activities for learning more about cultural humility. | [65] |

| The Honestly Adoption Company | Provides mentorship, support, training, resources, and learning materials for adoptive parents. See the “Resources” page for a database of resources focused on trauma-informed care, race, and writings from adult adoptees and former foster youth. | [66] |

| Multicultural Adoption Plan | Questions and critical prompts for parents considering transracial adoption. | [67] |

| Transracial Adoption Resources | A list of helpful transracial adoption resources for families, including topics such as racism, identity, and culture. | [57] |

| Trust-Based Relational Intervention® (TBRI) | An empirical peer-reviewed article describing the TBRI, a trauma-informed approach to care. | [68] |

| Trust-Based Relational Intervention® Resources | A list of TBRI resources. See the “About” page and dropdown for more info on TBRI. | [69] |

References

- Silverman, A.B. Outcomes of transracial adoption. Future Child. 1993, 3, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barn, R. ‘Doing the right thing’: Transracial adoption in the USA. In Mothering, Mixed Families and Racialised Boundaries; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 9–27. [Google Scholar]

- Nazaryan, L. Interracial adoption: Is a colorblind adoption a good idea in a color-conscious society? J. Juv. Law 2003, 23, 100–111. [Google Scholar]

- Choy, C.C. Global Families: A History of Asian International Adoption in America; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hague Conference on Private International Law (HCCH). Convention on Protection of Children and Co-Operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption. 29 May 1993. Available online: https://www.hcch.net/en/instruments/conventions/full-text/?cid=69 (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. Trends in US Adoptions: 2008–2012; Child Welfare Information Gateway: Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

- Children’s Bureau. Trends in Foster Care and Adoption: FY 2010–2019; US Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/cb/trends_fostercare_adoption_10thru19.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Alvarez, P.; Visual Capitalist. What does the global decline of the fertility rate look like? World Econ. Forum 2022. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/06/global-decline-of-fertility-rates-visualised/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Kim, S.K. Abandoned babies: The backlash of South Korea’s Special Adoption Act. Wash. Int. Law J. 2015, 24, 709–725. Available online: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1708&context=wilj (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Koh, E.; Hanlon, R.; Daughtery, L.; Lindner, A. Adoption by the Numbers: 2019–2020; National Council for Adoption: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://adoptioncouncil.org/research/adoption-by-the-numbers/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- US Department of State. FY 2015 Annual Report on Intercountry Adoption; Bureau of Consular Affairs: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. Available online: https://travel.state.gov/content/dam/aa/pdfs/2015Annual_Intercountry_Adoption_Report.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Children’s Bureau. The AFCARS Report, No. 27; US Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/cb/afcarsreport27.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- US Department of State. Annual Report on Intercountry Adoption, No. 12; Bureau of Consular Affairs: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://travel.state.gov/content/dam/NEWadoptionassets/pdfs/FY%202019%20Annual%20Report%20.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Children’s Bureau. The AFCARS Report, No. 29; US Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/cb/afcars-report-29.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- US Department of State. Annual Report on Intercountry Adoption, No. 14; Bureau of Consular Affairs: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://travel.state.gov/content/dam/NEWadoptionassets/pdfs/FY21%20Annual%20Report%20on%20Intercountry%20Adoption.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- US Department of State. FY 2023 Annual Report on Intercountry Adoption; Bureau of Consular Affairs: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/Intercountry-Adoption.html (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Samuels, G.E.M. Doing Race, Family, and Culture Through Transracial Adoption. [Webinar Transcript]. EmbraceRace 2019. Available online: https://www.embracerace.org/resources/doing-race-family-culture-through-transracial-adoption (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- De Bourbon, S.L. Indigenous Genocidal Tracings: Slavery, Transracial Adoption, and the Indian Child Welfare Act. Ph.D. Thesis, UC Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.M. The transracial adoption paradox: History, research, and counseling implications of cultural socialization. Couns. Psychol. 2003, 31, 711–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, C.; Hawkins-Leon, C.G. The transracial adoption debate: Counseling and legal implications. J. Couns. Dev. 2002, 80, 433–440. Available online: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A95204661/AONE?u=txshracd2588&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=86095025 (accessed on 28 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Goss, D. The complexities of mixed families: Transracial adoption as a humanitarian project. Genealogy 2022, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P.K. The trouble with the Multiethnic Placement Act: An empirical look at transracial adoption. Sociol. Perspect. 2006, 49, 559–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifelong Adoptions. Adoption Statistics. Adoptive Parent Resources. 2022. Available online: https://www.lifelongadoptions.com/adoption-statistics (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Trenka, J.J.; Oparah, J.C.; Shin, S.Y. (Eds.) Outsiders Within: Writing on Transracial Adoption; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Park-Taylor, J.; Wing, H.M. Microfictions and microaggressions: Counselors’ work with transracial adoptees in schools. Prof. Sch. Couns. 2020, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Y.R. Adoption of children of color from the child welfare system. In Children of Color in the Child Welfare System: Psychological Research and Best Practices; Harris, Y.R., Carpenter, G.J.O., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; pp. 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, G.E.M. Epistemic trauma and transracial adoption: Author(iz)ing folkways of knowledge and healing. Child Abuse Negl. 2022, 130, 105588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godon-Decoteau, D.; Ramsey, P.G. Positive and negative aspects of transracial adoption: An exploratory study from Korean transracial adoptees’ perspectives. Adopt. Q. 2018, 21, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juffer, F.; van IJzendoorn, M.H. Adoptees do not lack self-esteem: A meta-analysis of studies on self-esteem of transracial, international, and domestic adoptees. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 133, 1067–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, S.F. Relational-cultural theory: A supportive framework for transracial adoptive families. Fam. J. 2022, 30, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, E.E.; Baden, A.L.; Ferguson, A.L.; Smith, L. The intersection of race and adoption: Experiences of transracial and international adoptees with microaggressions. J. Fam. Psychol. 2022, 36, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden, A.L.; Sharma, S.M.; Balducci, S.; Ellis, L.; Randall, R.; Kwon, D.; Harrington, E.S. A trauma-informed substance use disorder prevention program for transracially adopted children and adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2022, 130, 105598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, A.J. Transracial adoption as continued oppression: Modern practice in context. Colum. Soc. Work Rev. 2022, 20, 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, E.J.; Samek, D.R.; Keyes, M.; McGue, M.; Iacono, W.G. Identity development in a transracial environment: Racial/ethnic minority adoptees in Minnesota. Adopt. Q. 2015, 18, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinnis, H.; Livingston, S.; Ryan, S.; Howard, J.A. Beyond Culture Camp: Promoting Healthy Identity Formation in Adoption; Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Available online: https://www.adoptioninstitute.org/old/publications/2009_11_BeyondCultureCamp.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Vonk, M.E.; Lee, J.; Crolley-Simic, J. Cultural socialization practices in domestic and international transracial adoption. Adopt. Q. 2010, 13, 227–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benet-Martínez, V.; Lee, F.; Cheng, C.-Y. Bicultural identity integration: Components, psychosocial antecedents, and outcomes. In Handbook of Advances in Culture and Psychology; Gelfand, M.J., Chiu, C.-Y., Hong, Y.-Y., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 244–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, K. Biracial and Bicultural Identity Formation: Lessons Garnered from Sense of Belonging and Code-Switching in Fostering Optimal Psychological Wellbeing and Mental Health. Ph.D. Thesis, Florida Institute of Technology, Melbourne, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Manzi, C.; Ferrari, L.; Rosnati, R.; Benet-Martinez, V. Bicultural identity integration of transracial adolescent adoptees: Antecedents and outcomes. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2014, 45, 888–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, H.K.; Cogburn, M. Piaget. In StatPearls [Web]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448206/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Jabbari, B.; Rouster, A.S. Family dynamics. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32809322/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- McLeod, S. Albert Bandura’s social learning theory. Simply Psychol. 2023. Available online: https://www.simplypsychology.org/bandura.html (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Wang, Y.; Benner, A.D.; Kim, S.Y. The cultural socialization scale: Assessing family and peer socialization toward heritage and mainstream cultures. Psychol. Assess. 2015, 27, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baden, A.L.; Treweeke, L.M.; Ahluwalia, M.K. Reclaiming culture: Reculturation of transracial and international adoptees. J. Couns. Dev. 2012, 90, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drazba, A. The Role of Reculturation Peer Interactions on Mental Health and Wellbeing Among Transracial Chinese Adoptees. Ph.D. Thesis, Palo Alto University, Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Huh, N.S.; Reid, W.J. Intercountry, transracial adoption, and ethnic identity: Korean example. Int. Soc. Work 2000, 43, 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Cloonan, V.; Hatfield, T.; Branco, S.; Dean, L. The racial and ethnic identity development process for adult Colombian adoptees. Genealogy 2023, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straughan, H.H.; Hoyt-Oliver, J.; Anderson, C. Parental understanding of cultural difference: A study of transracially adopting couples. Fam. Soc. 2025, 106, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilo, S.A.; Semler, M.R.; Rameau, S. The sum of all parts: A multi-level exploration of racial and ethnic identity formation during emerging adulthood. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0284275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castner, J.; Foli, K.J. Racial identity and transcultural adoption. Online J. Issues Nurs. 2022, 27, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarov, A.R. Transracial adoption brings lessons in cultural diversity: Arlington families share their stories. Arlington Mag. 2016. Available online: https://www.arlingtonmagazine.com/transracial-adoption-brings-lessons-in-cultural-diversity/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- RainbowKids. Adoption: Paperwork and Documents Needed. RainbowKids Adoption and Child Welfare Advocacy. 2013. Available online: https://www.rainbowkids.com/adoption-stories/adoption-paperwork-and-documents-needed-1304 (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Greene-Moton, E.; Minkler, M. Cultural competence or cultural humility? Moving beyond the debate. Health Promot. Pract. 2020, 21, 142–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adopt US Kids. Seven suggestions for a successful transracial adoption: Advice and considerations shared by adoptive parents and child welfare professionals. Adopt US Kids. 2021. Available online: https://adoptuskids.org/adoption-and-foster-care/how-to-adopt-and-foster/envisioning-your-family/transracial-adoption (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Tan, T.X.; Rice, J.L.; Mahoney, E.E. Developmental delays at arrival and postmenarcheal Chinese adolescents’ adjustment. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2015, 85, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adopt US Kids. Keeping siblings together. Adopt US Kids n.d. Available online: https://adoptuskids.org/meet-the-children/children-in-foster-care/about-the-children/keeping-siblings-together (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Roorda, R.M. In Their Voices: Black Americans on Transracial Adoption; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Considering Adoption. Adopting a family member from foster care. Considering Adoption n.d. Available online: https://consideringadoption.com/foster-care/about-the-children/adopting-family-member-foster-care/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Winokur, M.; Holtan, A.; Batchelder, K.E. Kinship care for the safety, permanency, and well-being of children removed from the home for maltreatment: A systematic review. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2014, 10, 1–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.A.; Zhang, E.; Liu, C.H. Potential impact of COVID-19-related racial discrimination on the health of Asian Americans. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, 1624–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, G.S.; Shah, T.N. When perceptions are fragile but enduring: An Asian American reflection on COVID-19. J. Humanist. Psychol. 2020, 60, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing, H.M.; Park-Taylor, J. From model minority to racial threat: Chinese transracial adoptees’ experience navigating the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian Am. J. Psychol. 2022, 13, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heritage Camps for Adoptive Families. Anti-Racism Toolkit. Available online: https://www.heritagecamps.org/anti-racism-toolkit/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Child Trauma Academy. CTA Library. Available online: https://www.childtrauma.org/cta-library (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- University of Oregon Division of Equity and Inclusion. Cultural Humility Toolkit. Available online: https://inclusion.uoregon.edu/cultural-humility-toolkit (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Nurturing Our Village. The Honestly Adoption Company. Available online: https://www.nurturingourvillage.org/resources/the-honestly-adoption-company/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- A Family for Every Child. Transracial Adoption Resources. Available online: https://www.afamilyforeverychild.org/transracial-adoption-resources/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Purvis, K.B.; Cross, D.R.; Dansereau, D.F.; Parris, S.R. Trust-based relational intervention (TBRI): A systemic approach to complex developmental trauma. Child Youth Serv. 2013, 34, 360–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Texas Christian University. Karyn Purvis Institute of Child Development: Resources. Available online: https://child.tcu.edu/resources/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

| Identity Integration Concepts | Survey Questions | Interview Semi-Structured Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Cultural Socialization | ||

| Birth culture identity | Be encouraged to explore identity. | Racial identity (preference) |

| Comfort zone | Desire to learn more. | Family (learning process) |

| Positive outlooks | Participate in activities. | External support |

| Reculturation | ||

| Discuss race topics | Minimize differences. | Communication (feelings) |

| Celebrate birth culture | Feel discriminated. | Search (birth culture, siblings) |

| Identify race-related questions | Fit in with same-race groups. | Challenges and suggestions |

| Search for more and create stories. | ||

| Aware of sibling group adoption. | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheung, M.; Minor, K.; Adams, E.M.; Park, H.A. Transracial Adoption Among Asian Youth: Transitioning Through an Integrative Identity. Adolescents 2025, 5, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5040065

Cheung M, Minor K, Adams EM, Park HA. Transracial Adoption Among Asian Youth: Transitioning Through an Integrative Identity. Adolescents. 2025; 5(4):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5040065

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheung, Monit, Katie Minor, Elisabeth M. Adams, and Hailey A. Park. 2025. "Transracial Adoption Among Asian Youth: Transitioning Through an Integrative Identity" Adolescents 5, no. 4: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5040065

APA StyleCheung, M., Minor, K., Adams, E. M., & Park, H. A. (2025). Transracial Adoption Among Asian Youth: Transitioning Through an Integrative Identity. Adolescents, 5(4), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5040065