Exploring the Psychological and Social Dynamics of Steroid and Performance-Enhancing Drug (PED) Use Among Late Adolescents and Emerging Adults (16–22): A Thematic Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Changing Body Ideals and Pressures Among Adolescents and Emerging Adults

1.2. The Hidden Onset of PED Use in Adolescents and Emerging Adults

1.3. Understanding Steroids and Performance-Enhancing Drugs: Beyond Supplements and Shakes

1.4. Physical and Psychological Impacts of Steroid and PED Use in Youth

1.5. Psychological and Emotional Drivers of Use

1.6. Muscle Dysmorphia and Body Distortion

1.7. Limitations of Current Research and the Need for Qualitative Understanding

1.8. Study Aim and Research Questions

- -

- What emotional and cognitive processes underlie the decision to engage in PED use among adolescents and emerging adults?

- -

- How do young users construct meaning around their bodily goals, daily routines, and perceived transformations?

- -

- In what ways do gender expectations, peer dynamics, and cultural narratives influence the initiation and continuation of PED use?

- -

- How do participants retrospectively interpret the consequences—emotional, social, and physical—of their engagement with PEDs?

2. Method

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Interview Protocol

- (1)

- Early bodily self-perception and body talk in adolescence;

- (2)

- First encounters with fitness culture and body ideals;

- (3)

- The onset of steroid or PED use and influencing factors;

- (4)

- Emotional and psychological drivers such as anxiety, validation needs, or perfectionism;

- (5)

- Secrecy, family dynamics, and avoidance of parental discovery;

- (6)

- Evolving perceptions of the body and signs of dysmorphia;

- (7)

- Gender-based and sociocultural narratives around appearance and masculinity;

- (8)

- Perceived risks, regrets, and bodily harm;

- (9)

- Future projections, identity formation, and meaning-making.

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Researcher Positionality and Reflexivity

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

Participant Characteristics

4. Discussion

4.1. Psychological and Developmental Interpretations

4.2. Gendered Experiences and Social Comparison

4.3. Secrecy, Autonomy, and Agency

4.4. Cultural Specificity and Socioeconomic Context

4.5. Implications for Clinical Practice, Prevention, and Policy

4.6. Limitations

4.7. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PED | Performance Enhancing Dru |

| AAS | Anabolic Androgenic Steroid |

| BDD | Body Dysmorphic Disorder |

| IGF1 | Insulin Like Growth Factor 1 |

| SARMs | Selective Androgen Receptor Modulators |

| hGH | Human Growth Hormone |

| MS | Teams Microsoft Teams |

| MD | Muscle Dysmorphia |

References

- Vankerckhoven, L.; Claes, L.; Raemen, L.; Palmeroni, N.; Eggermont, S.; Luyckx, K. Longitudinal associations among identity, internalization of appearance ideals, body image, and eating disorder symptoms in community adolescents and emerging adults: Adaptive and maladaptive pathways. J. Youth Adolesc. 2025, 54, 290–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincente-Benito, I.; Ramírez-Durán, M.D.V. Influence of social media use on body image and well-being among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2023, 61, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, A. The ideal of the perfect body. In The Body in the Mind: Exercise Addiction, Body Image and the Use of Enhancement Drugs; Cambridge University Press: Singapore, 2023; pp. 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Ganson, K.T.; Nagata, J.M. Adolescent and young adult use of muscle-building dietary supplements: Guidance for assessment and harm reduction approaches to mitigate risks. J. Adolesc. Health 2024, 75, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byatt, D.; Bussey, K.; Croft, T.; Trompeter, N.; Mitchison, D. Prevalence and correlates of anabolic–androgenic steroid use in Australian adolescents. Nutrients 2025, 17, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdoli, M.; Scotto Rosato, M.; Desousa, A.; Cotrufo, P. Cultural differences in body image: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, M.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F.; Rubio-Zarapuz, A.; Villanueva-Tobaldo, C.V.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J. Body perceptions and psychological well-being: A review of the impact of social media and physical measurements on self-esteem and mental health with a focus on body image satisfaction and its relationship with cultural and gender factors. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choukas-Bradley, S.; Roberts, S.R.; Maheux, A.J.; Nesi, J. The perfect storm: A developmental–sociocultural framework for the role of social media in adolescent girls’ body image concerns and mental health. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 25, 681–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, D.M. The Influencer Effect: Exploring the Persuasive Communication Tactics of Social Media Influencers in the Health and Wellness Industry. Ph.D. Thesis, Liberty University, Lynchburg, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Imran, F.H. From Zero to Hero, with the Man in the Mirror: Engagement of Performance Enhancing Drugs (PEDs) in Young Males. Ph.D. Thesis, University College Dublin, School of Medicine, Dublin, Ireland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- McComb, S.E.; Mills, J.S. The effect of physical appearance perfectionism and social comparison to thin-, slim-thick-, and fit-ideal Instagram imagery on young women’s body image. Body Image 2022, 40, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, P.K. Instagram ideals: College Women’s Body Image and Social Comparison. Master’s Thesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, S.R.; Maheux, A.J.; Hunt, R.A.; Ladd, B.A.; Choukas-Bradley, S. Incorporating social media and muscular ideal internalization into the tripartite influence model of body image: Towards a modern understanding of adolescent girls’ body dissatisfaction. Body Image 2022, 41, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, A.T.; Jarman, H.K.; Doley, J.R.; McLean, S.A. Social media use and body dissatisfaction in adolescents: The moderating role of thin- and muscular-ideal internalisation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheiber, R.; Diehl, S.; Karmasin, M. Socio-cultural power of social media on orthorexia nervosa: An empirical investigation on the mediating role of thin-ideal and muscular internalization, appearance comparison, and body dissatisfaction. Appetite 2023, 185, 106522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganson, K.T.; Hallward, L.; Cunningham, M.L.; Murray, S.B.; Nagata, J.M. Anabolic-androgenic steroid use: Patterns of use among a national sample of Canadian adolescents and young adults. Perform. Enhanc. Health 2023, 11, 100241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, L.T.J.; Paoli, L. Social media influencers, YouTube & performance and image enhancing drugs: A narrative-typology. Perform. Enhanc. Health 2023, 11, 100266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, H.G., Jr.; Gruber, A.J.; Choi, P.; Olivardia, R.; Phillips, K.A. Muscle dysmorphia: An underrecognized form of body dysmorphic disorder. Psychosomatics 1997, 38, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchison, D.; Mond, J.; Griffiths, S.; Hay, P.; Nagata, J.M.; Bussey, K.; Trompeter, N.; Lonergan, A.; Murray, S.B. Prevalence of muscle dysmorphia in adolescents: Findings from the EveryBODY study. Psychol. Med. 2022, 52, 3142–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gestsdottir, S.; Kristjansdottir, H.; Sigurdsson, H.; Sigfusdottir, I.D. Prevalence, mental health and substance use of anabolic steroid users: A population-based study on young individuals. Scand. J. Public Health 2021, 49, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawash, A.; Zia, H.; Al-Shehab, U.; Lo, D.F. Association of body dysmorphic–induced anabolic-androgenic steroid use with mental health outcomes: A systematic review. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2023, 25, 49582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaiser, C.; Laskowski, N.M.; Müller, R.; Abdulla, K.; Sabel, L.; Reque, C.B.; Brandt, G.; Paslakis, G. The relationship between anabolic androgenic steroid use and body image, eating behavior, and physical activity by gender: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2024, 163, 105772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, H.J.; Nyhagen, L.; Thurnell-Read, T. Moral, health, and aesthetic risks: Performance-enhancing drug use and the culture of silence in the UK strongwoman community. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2024, 17, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piplios, O.; Yager, Z.; McLean, S.A.; Griffiths, S.; Doley, J.R. Appearance and performance factors associated with muscle building supplement use and favourable attitudes towards anabolic steroids in adolescent boys. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1241024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, N.N. A triad of physical masculinities: Examining multiple ‘hegemonic’ bodybuilding identities in anabolic-androgenic steroid (AAS) online discussion groups. Deviant Behav. 2023, 44, 1498–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badenes-Ribera, L.; Longobardi, C.; Gastaldi, F.G.M.; Fabris, M.A. The roles of attachment to parents and gender in the relationship between Parental criticism and muscle dysmorphia symptomatology in adolescence. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2021, 26, 513–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabris, M.A.; Badenes-Ribera, L.; Longobardi, C.; Demuru, A.; Dawid Konrad, Ś.; Settanni, M. Homophobic bullying victimization and muscle dysmorphic concerns in men having sex with men: The mediating role of paranoid ideation. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 3577–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganson, K.T.; Nguyen, L.; Ali, A.R.H.; Hallward, L.; Jackson, D.B.; Testa, A.; Nagata, J.M. Associations between social media use, fitness- and weight-related online content, and use of legal appearance- and performance-enhancing drugs and substances. Eat. Behav. 2023, 49, 101736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linhares, B.L.; Miranda, E.P.; Cintra, A.R.; Reges, R.; Torres, L.O. Use, misuse and abuse of testosterone and other androgens. Sex. Med. Rev. 2022, 10, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, M.L.; Griffiths, S. Appearance-and performance-enhancing substances including anabolic-androgenic steroids among boys and men. In Eating Disorders in Boys and Men; Springer Cham: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, K.; Schiefner, F.; Rudolf, M.; Awiszus, F.; Junne, F.; Vogel, M.; Lohmann, C.H. Long-term effects of doping with anabolic steroids during adolescence on physical and mental health. Orthopädie 2024, 53, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnecaze, A.K.; O’Connor, T.; Burns, C.A. Harm reduction in male patients actively using anabolic androgenic steroids (AAS) and performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs): A review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 2055–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, A.R.; Cope, E.; Bailey, R.; Koenen, K.; Dumon, D.; Theodorou, N.C.; Chanal, B.; Laurent, D.S.; Müller, D.; Andrés, M.P.; et al. Children’s first experience of taking anabolic-androgenic steroids can occur before their 10th birthday: A systematic review identifying 9 factors that predicted doping among young people. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macho, J.; Mudrak, J.; Slepicka, P. Enhancing the self: Amateur bodybuilders making sense of experiences with appearance and performance-enhancing drugs. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 648467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamrack, M. Exercise and Sport Pharmacology; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, A.; Andreasson, J. “Yay, another lady starting a log!”: Women’s fitness doping and the gendered space of an online doping forum. Commun. Sport 2021, 9, 988–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, A.L.; Pope HGJr Bhasin, S. The health threat posed by the hidden epidemic of anabolic steroid use and body image disorders among young men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 104, 1069–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, N.P. The Balancing Act: How Risk is Experienced, Navigated and Perceived by Users of Performance Enhancing Drugs. Ph.D. Thesis, Kingston University, London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, H.G., Jr.; Wood, R.I.; Rogol, A.; Nyberg, F.; Bowers, L.; Bhasin, S. Adverse health consequences of performance-enhancing drugs: An Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocr. Rev. 2014, 35, 341–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windfeld-Mathiasen, J.; Christoffersen, T.; Strand, N.A.W.; Dalhoff, K.; Andersen, J.T.; Horwitz, H. Psychiatric morbidity among men using anabolic steroids. Depress Anxiety 2022, 39, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alizadeh Pahlavani, H.; Veisi, A. Possible consequences of the abuse of anabolic steroids on different organs of athletes. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, P.; Smit, D.L.; de Ronde, W. Anabolic–androgenic steroids: How do they work and what are the risks? Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1059473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahi, A.; Nagpal, R.; Verma, S.; Narula, A.; Tonk, R.K.; Kumar, S. A comprehensive review on current analytical approaches used for the control of drug abuse in sports. Microchem. J. 2023, 191, 108834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, J.M.; Hazzard, V.M.; Ganson, K.T.; Austin, S.B.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Eisenberg, M.E. Muscle-building behaviors from adolescence to emerging adulthood: A prospective cohort study. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 27, 101778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, J.R.; Faigenbaum, A.D.; Ratamess, N.A.; Ross, R.; Kang, J.I.E.; Tenenbaum, G. Nutritional supplementation and anabolic steroid use in adolescents. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2008, 40, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, L. The Truth About Steroids; The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Mcllvain, V.; Rosenberg, J.; Donovan, L.; Desai, P.; Kim, J.Y. The mechanisms of anabolic steroids, selective androgen receptor modulators and myostatin inhibitors. Korean J. Sports Med. 2022, 40, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albano, G.D.; Amico, F.; Cocimano, G.; Liberto, A.; Maglietta, F.; Esposito, M.; Rosi, G.L.; Di Nunno, N.; Salerno, M.; Montana, A. Adverse effects of anabolic-androgenic steroids: A literature review. Healthcare 2021, 9, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, R.D.A.; Gualano, B.; Teixeira, T.A.; Nascimento, B.C.; Hallak, J. Abusive use of anabolic androgenic steroids, male sexual dysfunction and infertility: An updated review. Front. Toxicol. 2024, 6, 1379272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Girolamo, F.G.; Biasinutto, C.; Mangogna, A.; Fiotti, N.; Vinci, P.; Pisot, R.; Mearelli, F.; Simunic, B.; Roni, C.; Biolo, G. Metabolic consequences of anabolic steroids, insulin, and growth hormone abuse in recreational bodybuilders: Implications for the World Anti-Doping Agency Passport. Sports Med. Open 2024, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirla, A.; Vesa, C.M.; Cavalu, S. Severe cardiac and metabolic pathology induced by steroid abuse in a young individual. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windfeld-Mathiasen, J.; Heerfordt, I.M.; Dalhoff, K.P.; Andersen, J.T.; Andersen, M.A.; Johansson, K.S.; Biering-Sørensen, T.; Olsen, F.J.; Horwitz, H. Cardiovascular disease in anabolic androgenic steroid users. Circulation 2025, 151, 828–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momoh, R. Anabolic-androgenic steroid abuse causes cardiac dysfunction. Am. J. Mens Health 2024, 18, 15579883241249647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duraisamy, P.; Ravi, S.; Krishnan, M.; Martin, L.C.; Manikandan, B.; Janarthanan, S.; Manikandan, R. Destructive effects of steroidal drug abuse and their immunological impact. In Steroids and Their Medicinal Potential; Bentham Science Publishers: Singapore, 2023; pp. 286–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, N.; Patil, J. Prediction of health hazards caused due to excess use of steroid consumption on liver, heart, and lung of human body. In International Conference on Frontiers of Intelligent Computing: Theory and Applications; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2024; pp. 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piatkowski, T.; Coomber, R.; Francis, C.; Kill, E.; Davey, G.; Cresswell, S.; White, A.; Harding, M.; Blakey, K.; Reeve, S.; et al. The world’s first anabolic-androgenic steroid testing trial: A two-phase pilot combining chemical analysis, results dissemination and community feedback. Addiction 2025, 7, 1366–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Hulst, A.M.; Peersmann, S.H.M.; Akker, E.L.T.v.D.; Schoonmade, L.J.; Heuvel-Eibrink, M.M.v.D.; Grootenhuis, M.A.; van Litsenburg, R.R.L. Risk factors for steroid-induced adverse psychological reactions and sleep problems in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A systematic review. Psychooncology 2021, 30, 1009–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, B.S.; Hildebrandt, T.; Wallisch, P. Anabolic–androgenic steroid use is associated with psychopathy, risk-taking, anger, and physical problems. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klonteig, S.; Scarth, M.; Bjørnebekk, A. Sleep pathology and use of anabolic androgen steroids among male weightlifters in Norway. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, H.G., Jr.; Kanayama, G.; Hudson, J.I.; Kaufman, M.J. Review Article: Anabolic-androgenic steroids, violence, and crime: Two cases and literature review. Am. J. Addict. 2021, 30, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagun, B.; Altug, S. Anabolic-androgenic steroids are linked to depression and anxiety in male bodybuilders: The hidden psychogenic side of anabolic androgenic steroids. Ann. Med. 2024, 56, 2337717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, J.M.; Padilha, M.C.; Chagas, S.V.; Baker, J.S.; Mullen, C.; Neto, L.V.; Neto, F.R.A.; Cruz, M.S. Effective treatment and prevention of attempted suicide, anxiety, and aggressiveness with fluoxetine, despite proven use of androgenic anabolic steroids. Drug Test. Anal. 2021, 13, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacPhail, D.C.; Oberle, C.D. Seeing shred: Differences in muscle dysmorphia, orthorexia nervosa, depression, and obsessive-compulsive tendencies among groups of weightlifting athletes. Perform. Enhanc. Health 2022, 10, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusseau, T.A.; Burns, R.D. Associations of physical activity, school safety, and non-prescription steroid use in adolescents: A structural equation modeling approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, S.; Phan, P.; Law, J.Y.; Choi, E.; Chandran, N.S. Qualitative analysis of topical corticosteroid concerns, topical steroid addiction and withdrawal in dermatological patients. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e060867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havnes, I.A.; Jørstad, M.L.; Innerdal, I.; Bjørnebekk, A. Anabolic-androgenic steroid use among women—A qualitative study on experiences of masculinizing, gonadal and sexual effects. Int. J. Drug Policy 2021, 95, 102876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.B.; Canzona, M.R.; Puccinelli-Ortega, N.; Little-Greene, D.; Duckworth, K.E.; Fingeret, M.C.; Ip, E.H.; Sanford, S.D.; Salsman, J.M. A qualitative assessment of body image in adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer. Psychooncology 2021, 30, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frederick, D.A.; Tylka, T.L.; Rodgers, R.F.; Pennesi, J.-L.; Convertino, L.; Parent, M.C.; Brown, T.A.; Compte, E.J.; Cook-Cottone, C.P.; Crerand, C.E.; et al. Pathways from sociocultural and objectification constructs to body satisfaction among women: The US Body Project I. Body Image 2022, 41, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.; Hoare, E.; Allender, S.; Olive, L.; Leech, R.M.; Winpenny, E.M.; Jacka, F.; Lotfalian, M. A longitudinal study of lifestyle behaviours in emerging adulthood and risk for symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 327, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, C.G.; Pope, H.G.; Menard, W.; Fay, C.; Olivardia, R.; Phillips, K.A. Clinical features of muscle dysmorphia among males with body dysmorphic disorder. Body Image 2005, 2, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravn, S.; Coffey, J. ‘Steroids, it’s so much an identity thing!’perceptions of steroid use, risk and masculine body image. J. Youth Stud. 2016, 19, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Filho, C.A.; Tirico, P.P.; Stefano, S.C.; Touyz, S.W.; Claudino, A.M. Systematic review of the diagnostic category muscle dysmorphia. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2016, 50, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türksoy, N. Consumerism, popular culture, and religion between two continents: The Turkish case. In The Routledge Handbook of Lifestyle Journalism; Routledge: London, UK, 2025; pp. 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervin, N.; Mokhtar, M. The interpretivist research paradigm: A subjective notion of a social context. Int. J. Acad. Res. Prog. Educ. Dev. 2022, 11, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; Chen, M. A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeoye-Olatunde, O.A.; Olenik, N.L. Research and scholarly methods: Semi-structured interviews. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2021, 4, 1358–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riessman, C.K. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.A.; Osborn, M. Interpretive phenomenological analysis. In Qualitative Psychology: A practical Guide to Methods; Smith, J.A., Ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rorije, M.; Damen, S.; Janssen, M.J.; Minnaert, A. Applying Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development to understand autonomy development in children and youths with deafblindness: A systematic literature review. Front. Educ. 2023, 8, 1228905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holodynski, M.; Friedlmeier, W. Development of Emotions and Emotion Regulation; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Settanni, M.; Prino, L.E.; Fabris, M.A.; Longobardi, C. Muscle Dysmorphia and anabolic steroid abuse: Can we trust the data of online research? Psychiatry Res. 2017, 263, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category/Range | n (%) or M ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 16–22 | M = 19.1 (SD = 1.8) |

| Gender | Male (n = 19); Female (n = 7) | 26 (100%) |

| Education | High school (n = 10); University (n = 16) | — |

| Primary PED used | AAS (n = 20); SARMs (n = 4); Other (n = 2) | — |

| Duration of PED use | 3 months–3 years | M ≈ 1.4 years |

| Training frequency | 4–6 sessions per week | — |

| District of residence | Sarıyer (5); Beşiktaş (4); Bakırköy (4); Kadıköy (5); Kartal (4); Beylikdüzü (4) | — |

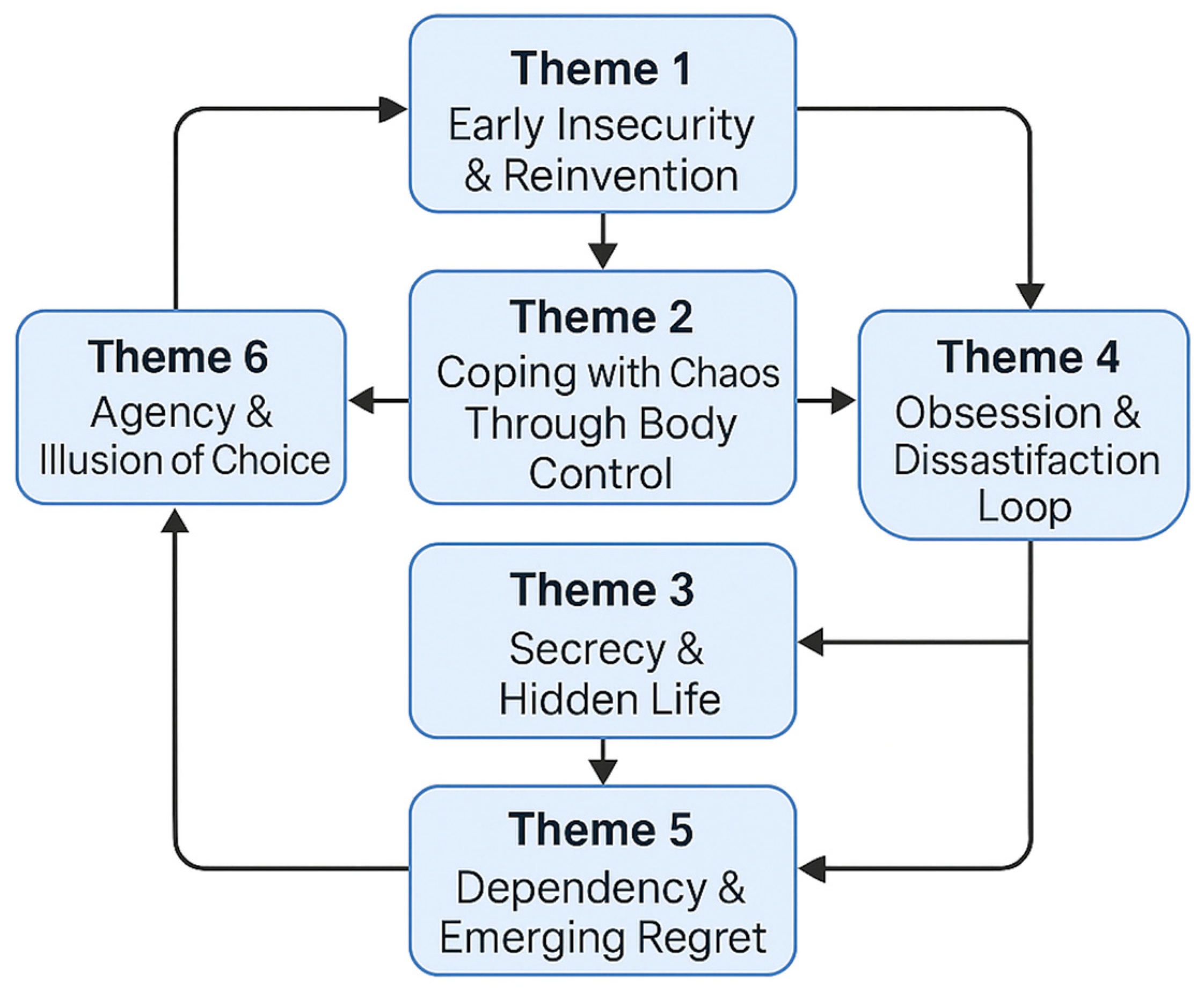

| Theme | Definition/Core Meaning | Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Early Insecurity & Reinvention | Feelings of inadequacy and invisibility drive the fantasy that bodily change will restore self-worth and social recognition. | “I wasn’t bullied, but no one noticed me. After I started training and using, even the way people said ‘hi’ changed.” |

| 2. Coping with Chaos Through Body Control | PED use serves as an emotional regulation strategy—creating stability and control amid academic, family, or social stress. | “When everything else feels like a mess, at least I can control this—how I look, how I train.” |

| 3. Secrecy & Hidden Life | Concealing PED use provides autonomy and protection from judgment, allowing users to define progress on their own terms. | “My parents think I take vitamins. It’s easier not to tell them—it’s my decision, my body.” |

| 4. Obsession & the Dissatisfaction Loop | Bodily achievement never feels sufficient; constant comparison fuels compulsive training and self-criticism. | “You hit a goal, then the goal changes. There’s no end to it.” |

| 5. Dependency & Emerging Regret | Emotional and identity-based dependence on PEDs develops; stopping use feels like losing control or self-worth. | “I know it’s not forever, but right now it’s the only thing that makes me proud of myself.” |

| 6. Agency & Illusion of Choice | PED use is framed as empowerment or protest against societal limits, yet this autonomy often reinforces dependency. | “In school I was average, but at the gym I’m someone. This body is the only thing I’ve built with my own hands.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Çınaroğlu, M.; Yılmazer, E.; Noyan Ahlatcıoğlu, E. Exploring the Psychological and Social Dynamics of Steroid and Performance-Enhancing Drug (PED) Use Among Late Adolescents and Emerging Adults (16–22): A Thematic Analysis. Adolescents 2025, 5, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5040063

Çınaroğlu M, Yılmazer E, Noyan Ahlatcıoğlu E. Exploring the Psychological and Social Dynamics of Steroid and Performance-Enhancing Drug (PED) Use Among Late Adolescents and Emerging Adults (16–22): A Thematic Analysis. Adolescents. 2025; 5(4):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5040063

Chicago/Turabian StyleÇınaroğlu, Metin, Eda Yılmazer, and Esra Noyan Ahlatcıoğlu. 2025. "Exploring the Psychological and Social Dynamics of Steroid and Performance-Enhancing Drug (PED) Use Among Late Adolescents and Emerging Adults (16–22): A Thematic Analysis" Adolescents 5, no. 4: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5040063

APA StyleÇınaroğlu, M., Yılmazer, E., & Noyan Ahlatcıoğlu, E. (2025). Exploring the Psychological and Social Dynamics of Steroid and Performance-Enhancing Drug (PED) Use Among Late Adolescents and Emerging Adults (16–22): A Thematic Analysis. Adolescents, 5(4), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5040063