Lessons Learned from a Mixed-Method Pilot of a Norms-Shifting Social Media Intervention to Reduce Teacher-Perpetrated School-Related Gender-Based Violence in Uganda

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Intervention

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Recruitment and Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

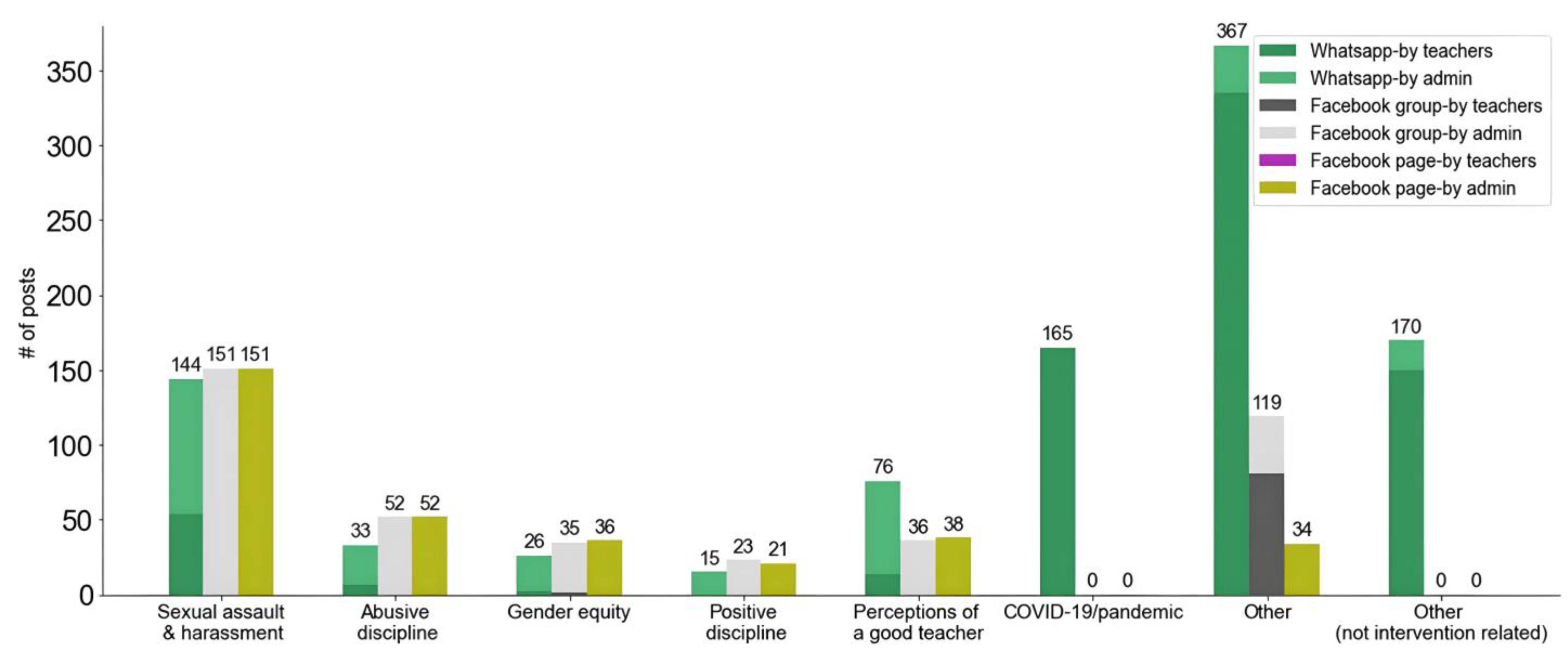

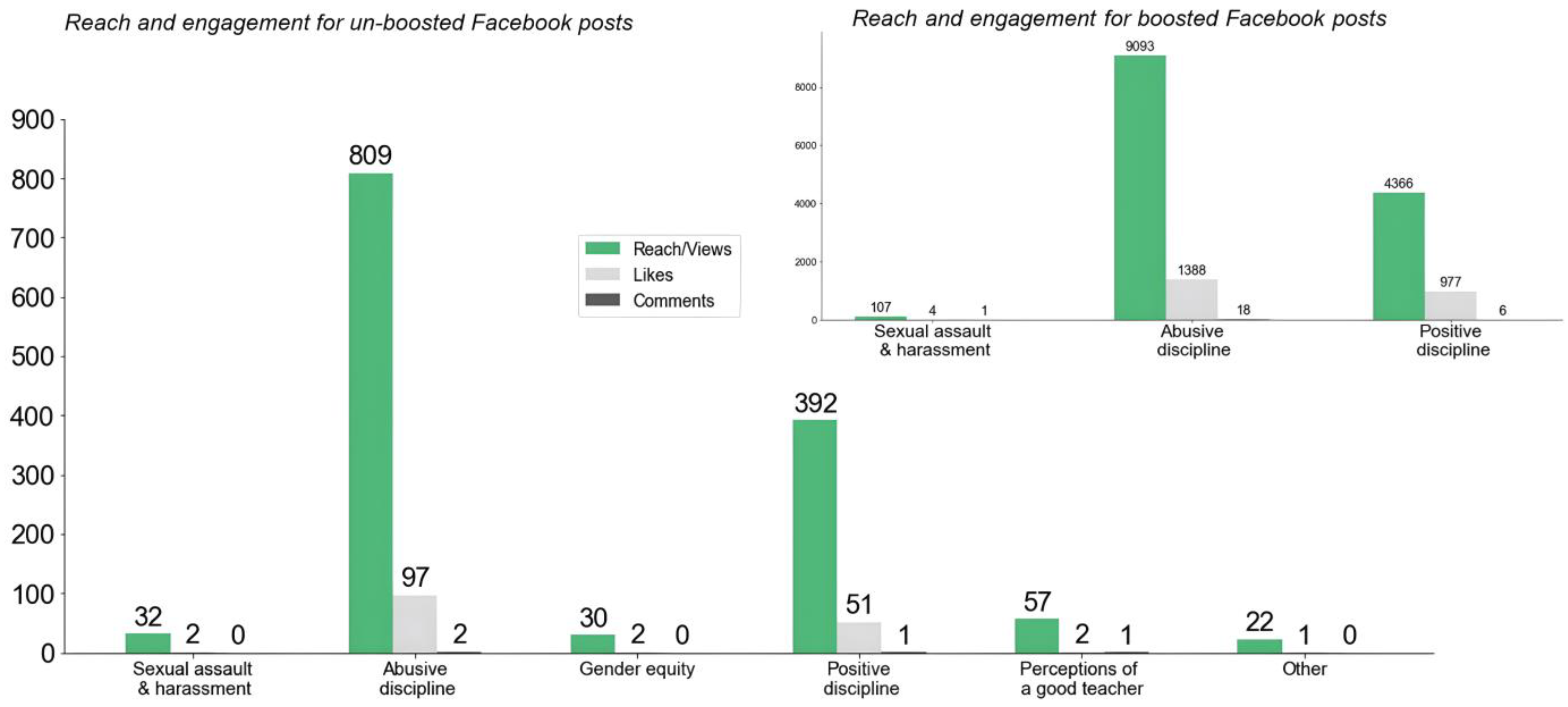

3.1. Intervention Reach and Engagement

3.2. Social Norms and Attitudes of Teachers Related to SRGBV

“We have a steadily progressive morally decaying society. So, we should not spare the stick. We should uphold the stick … for discipline, I have to cane [beat] them [students].”

“You’re scared but that is the truth my dear. I flog my own [students] to put them to order.”

“I think beating affects the child emotionally, psychologically sometimes these pupils’ behavior may be depicting what is happening to them, especially those children who are abused. They tend to be aggressive, so beating maybe just adding salt to their wounds and making school a living hell for them. That’s my view.”

“A child instead feels demotivated and feels like dropping out of school because his or her self-esteem has been lowered.”

“Calling children names is so hurtful and demoralizing. It has adverse effects to their self-esteem and outlook. It erodes their self-confidence and freedom of expression. Their active participation in class is curtailed.”

Respondent 1: “Beating a child is not a good idea to help him or her come out of trouble but instead have a serious talk with that child this will help you find a way of handling that child especially in class without hurting each other physically or emotionally that’s my thought thanks.”

Respondent 2: “Many educators who say such incendiary things do the same in their families and schools. Beating is the most effective way or else get the teachers the alternatives.”

Respondent 3: “Not all what our parents did was right. I think it was how they perceived the situation. Can we believe that there are outdated values and norms due to globalization? As when you practice them now you can be reprimanded. So, let’s apply values which suits today not yesterday.”

Respondent 4: “You have really spoilt the generation with minor excuse ... when someone has done wrong twice, he deserves some pain. Me, I can’t support any idea about stopping child beating so long as beating has been done properly that’s why we have a high number of undisciplined people in the community and it’s still increasing.”

“It’s poor upbringing of the child. There are those girls who like seducing our male teachers also. So, they end up making false accusations.”

“In fact, that’s [where] most teachers fall victim to sexual harassment of the young minors.”

“Teachers should focus on the ability of learners, however they should also be gender sensitive and treat all learners equally.”

“The world will be better and become the best place to live in because even in the eyes of GOD we are all equal.”

“All children are placed in the teacher’s hands to be handled equally.”

3.3. Implementation Learning

“When I had just started teaching, I did not know how to handle children and often lashed out at them. I am proud of myself now, because I am able to deal with children without resorting to demeaning remarks or violence.”

Prompt: “What do you feel about the myth that children seduce teachers and are really damaged by sexual abuse?”

Teacher comment: “It is not a myth. Children do seduce teachers after studying their weak areas. So, it is up to a teacher to stand his ground and keep his integrity.”

Prompt: “What can teachers do to let pupils know they are a safe person to talk to about sexual abuse?”

Teacher comment: “To have regular sex education sessions with pupils in or to provide them with enough space to express their feelings freely with teachers. Teachers should reach down to the earth and listen to pupils.”

Prompt: “Do teachers who call pupils harmful names or beat them deserve to be shunned?”

Teacher comment: “Beating and discipling are two different things. I flog mine seriously. We shall not raise undesirable and unruly children ... I always challenge people who are against caning [beating] to give alternatives and nothing has come out.”

Peer Influencer Comment: “Do you know the psychological effect of beating? There alternatives to beating children. Research has it that the most beaten children end up hooligans ... Stop damaging people’s children.”

“It has helped me solve problems because when we work together in the Everyday Heroes WhatsApp group, the challenges that children face can be solved and we can find solutions towards ending violence pupils face at school.”

“As teachers, we have been missing something about behavior change within ourselves but whenever they send topics and questions and we see how people discuss about behavior changes, solutions and ways on how we can change our attitudes, it helps us change from what we have been doing to the positive side and in doing that we are able to also uplift others.”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hillis, S.; Mercy, J.; Amobi, A.; Kress, H. Global Prevalence of Past-year Violence Against Children: A Systematic Review and Minimum Estimates. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20154079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Know Violence in Childhood. Ending Childhood Violence: The Role of Schools and the Education Sector; FXB International: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Global Working Group to End School-Related Gender Based Violence. Why Ending School-Related Gender-Based Violence (Srgbv) Is Critical to Sustainable Development; United Nations Girls’ Education Initiative (UNGEI): New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Devries, K.; Knight, L.; Petzold, M.; Merrill, K.G.; Maxwell, L.; Williams, A.; Cappa, C.; Chan, K.L.; Garcia-Moreno, C.; Hollis, N.; et al. Who perpetrates violence against children? A systematic analysis of age-specific and sex-specific data. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2018, 2, e000180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longobardi, C.; Prino, L.E.; Fabris, M.A.; Settanni, M. Violence in School: An Investigation of Physical, Psychological, and Sexual Victimization Reported by Italian Adolescents. J. Sch. Violence 2019, 18, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhanguzi, F.K. Gender and sexual vulnerability of young women in Africa: Experiences of young girls in secondary schools in Uganda. Cult. Health Sex. 2011, 13, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, A.A.; Boyack, M.; Cook, R.E.; Allen, E. School Connectedness and STEM Orientation in Adolescent Girls: The Role of Perceived Gender Discrimination and Implicit Gender-Science Stereotypes. Sex Roles 2021, 85, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillis, S.D.; Mercy, J.A.; Saul, J.R. The enduring impact of violence against children. Psychol. Health Med. 2017, 22, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodon, Q.; Fèvre, C.; Malé, A.; Nayihouba, H.; Nguyen, H. Ending Violence in Schools: An Investment Case; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Gender Dimensions of Violence Against Children and Adolescents; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kızıltepe, R.; Irmak, T.Y.; Eslek, D.; Hecker, T. Prevalence of violence by teachers and its association to students’ emotional and behavioral problems and school performance: Findings from secondary school students and teachers in Turkey. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 107, 104559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, P.; Franceschini, G.; Villani, A.; Corsello, G. Physical, psychological and social impact of school violence on children. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2019, 45, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibriya, S.; Tkach, B.; Ahu, J.; Gonzalez, N.V.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y. The Effects of School-Related Gender-Based Violence on Academic Performance: Evidence from Botswana, Ghana, and South Africa; United States Agency for International Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C.S.; Stone, E.A. Gender Stereotypes and Discrimination: How Sexism Impacts Development. Adv. Child Dev. Behav. 2016, 50, 105–133. [Google Scholar]

- Shaukat, S.; Siddiquah, A.; Pell, A.W. Gender Discrimination in Higher Education in Pakistan: A Survey of University Faculty. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 2014, 56, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntshuntshe, Z. School Teachers as Non-Violent Role Models. In Cultivating a Culture of Nonviolence in Early Childhood Development Centers and Schools; Muruti, R.D., Likando, G., Taukeni, S.G., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yavuzer, Y.; Rezzan, G. Teachers’ Responsibilities in Preventing School Violence: A Case Study in Turkey. Educ. Res. Rev. 2012, 7, 362–371. [Google Scholar]

- Devries, K.M.; Naker, D. Preventing teacher violence against children: The need for a research agenda. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e379–e380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Gender Labour and Social Development. Uganda Violence against Children Survey Findings from a National Survey; Ministry of Gender Labour and Social Development: Kampala, Uganda, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- BenYishay, A.; Sayers, R.; Wells, J. Secondary Analysis and Application of the Violence Against Children and Youth Surveys (VACS) for the Education Sector; AIDData, United States Agency for International Development (USAID): Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Parkes, J.; Bhatia, A.; Datzberger, S.; Nagawa, R.; Naker, D.; Devries, K. Addressing silences in research on girls’ experiences of teacher sexual violence: Insights from Uganda. Comp. Educ. 2022, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubaaie, G. Gender imbalances among students in Kyambogo University of Uganda and development implications. Direct Res. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Stud. 2020, 7, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Passages Project. Evaluation of Commitments Intervention: Baseline Assessment Report; Institute for Reproductive Health, Georgetown University: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, S.P.; Seko, Y.; Joshi, P. The impact of YouTube peer feedback on attitudes toward recovery from non-suicidal self-injury: An experimental pilot study. Digit Health 2018, 4, 2055207618780499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wombacher, K.; Reno, J.E.; Veil, S.R. NekNominate: Social Norms, Social Media, and Binge Drinking. Health Commun. 2017, 32, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskarpatyoti, B.; Biehl, H.; Spencer, J. Using Social Media Data to Understand Changes in Gender Norms; Measure Evaluation, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lutkenhaus, R.; McLarnon, C.; Walker, F. Norms-Shifting on Social Media: A Review of Strategies to Shift Norms among Adolescents and Young Adults Online. Rev. Commun. Res. 2023, in press.

- Fairbairn, J. Before #MeToo: Violence against Women Social Media Work, Bystander Intervention, and Social Change. Societies 2020, 10, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Liou, C. Using Social Media for the Prevention of Violence against Women: Lessons Learned from Social Media Communication Campaigns to Prevent Violence against Women in India, China and Viet Nam; Partners for Prevention: Bangkok, Thailand, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Sagarin, B.J. Principles of Interpersonal Influence. In Persuasion: Psychological Insights and Perspectives, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 143–169. [Google Scholar]

- Devries, K.M.; Allen, E.; Child, J.C.; Walakira, E.; Parkes, J.; Elbourne, D.; Watts, C.; Naker, D. The Good Schools Toolkit to prevent violence against children in Ugandan primary schools: Study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials 2013, 14, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devries, K.M.; Knight, L.; Allen, E.; Parkes, J.; Kyegombe, N.; Naker, D. Does the Good Schools Toolkit Reduce Physical, Sexual and Emotional Violence, and Injuries, in Girls and Boys equally? A Cluster-Randomised Controlled Trial. Prev. Sci. 2017, 18, 839–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devries, K.M.; Knight, L.; Child, J.C.; Mirembe, A.; Nakuti, J.; Jones, R.; Sturgess, J.; Allen, E.; Kyegombe, N.; Parkes, J.; et al. The Good School Toolkit for reducing physical violence from school staff to primary school students: A cluster-randomised controlled trial in Uganda. Lancet Glob. Health 2015, 3, e378–e386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIP). SBC Overview: Integrated Framework for Effective Implementation of the Social and Behavior Change High Impact Practices in Family Planning; HIP Partnership: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- High-Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). Digital Health for Social and Behavior Change: New Technologies, New Ways to Reach People; USAID: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cislaghi, B.; Heise, L. Theory and practice of social norms interventions: Eight common pitfalls. Glob. Health 2018, 14, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cislaghi, B.; Heise, L. Using social norms theory for health promotion in low-income countries. Health Promot. Int. 2019, 34, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cislaghi, B.; Denny, E.K.; Cissé, M.; Gueye, P.; Shrestha, B.; Shrestha, P.N.; Ferguson, G.; Hughes, C.; Clark, C.J. Changing Social Norms: The Importance of “Organized Diffusion” for Scaling Up Community Health Promotion and Women Empowerment Interventions. Prev. Sci. 2019, 20, 936–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Aims | Data Collection Method | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Social Media Tracking | Qualitative Social Media Listening | Post-Implementation Interviews | |

| 1. Describe the intervention’s reach and engagement | Yes | No | No |

| 2. Explore the social norms and attitudes voiced by teachers on Everyday Heroes social media groups | No | Yes | No |

| 3. Report on acceptability, challenges, and lessons learned from implementation and adaptation | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Post Topic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher | Administrator | Teacher | Administrator | |

| Intervention-related | 749 (42.0%) | 77 (94.8%) | 1 (1.2%) | 296 (88.6%) |

| Other | 533 (58.0%) | 4 (5.2%) | 81 (98.8%) | 38 (11.4%) |

| Total | 919 (100%) | 77 (100%) | 82 (100%) | 334 (100%) |

| Identified Challenge | Action |

|---|---|

| Teachers requested educational content on how to implement positive discipline techniques. | Posted links to educational information on positive discipline. |

| Some men voiced they felt attacked by posts on sexual harassment. | Revised posts to largely focus on the positive impact teachers can have and how they can prevent and report sexual harassment and abuse. |

| Participant burnout and fatigue related to posts on sexual harassment and abuse. | Varied content instead of posting repeated days of content on this topic. |

| Posts directly confronting harmful norms often had the unintended effect of reinforcing harmful norms. | Revised posts to focus on positive norms and positive influence of teachers. Included peer-influencers to comment on posts and shift discussion to focus on positive norms. |

| Some teachers posted content that graphically depicted child abuse. | Careful content moderation and removal of problematic teacher posts. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Uysal, J.; Chitle, P.; Akinola, M.; Kennedy, C.; Tumusiime, R.; McCarthy, P.; Gautsch, L.; Lundgren, R. Lessons Learned from a Mixed-Method Pilot of a Norms-Shifting Social Media Intervention to Reduce Teacher-Perpetrated School-Related Gender-Based Violence in Uganda. Adolescents 2023, 3, 199-211. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents3020015

Uysal J, Chitle P, Akinola M, Kennedy C, Tumusiime R, McCarthy P, Gautsch L, Lundgren R. Lessons Learned from a Mixed-Method Pilot of a Norms-Shifting Social Media Intervention to Reduce Teacher-Perpetrated School-Related Gender-Based Violence in Uganda. Adolescents. 2023; 3(2):199-211. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents3020015

Chicago/Turabian StyleUysal, Jasmine, Pooja Chitle, Marilyn Akinola, Catherine Kennedy, Rogers Tumusiime, Pam McCarthy, Leslie Gautsch, and Rebecka Lundgren. 2023. "Lessons Learned from a Mixed-Method Pilot of a Norms-Shifting Social Media Intervention to Reduce Teacher-Perpetrated School-Related Gender-Based Violence in Uganda" Adolescents 3, no. 2: 199-211. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents3020015

APA StyleUysal, J., Chitle, P., Akinola, M., Kennedy, C., Tumusiime, R., McCarthy, P., Gautsch, L., & Lundgren, R. (2023). Lessons Learned from a Mixed-Method Pilot of a Norms-Shifting Social Media Intervention to Reduce Teacher-Perpetrated School-Related Gender-Based Violence in Uganda. Adolescents, 3(2), 199-211. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents3020015