Abstract

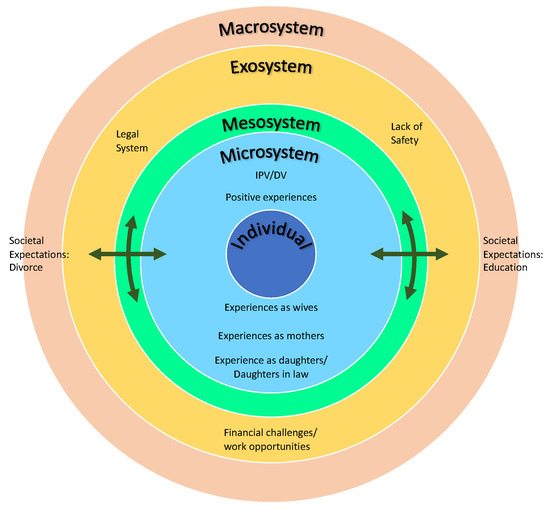

This study examined the lived experiences of Syrian refugee child brides to understand their needs as they navigate new social roles after marriage. A cross-sectional study was conducted in Lebanon using SenseMaker® to collect narratives from married Syrian girls age 13 and older and from their parents. Thematic analysis using inductive coding was performed. Identified themes were organized according to an adaptation of Bronfenbrenner’s socioecological theory of human development to present experiences across all levels of the girls’ interactions and potential influences. Themes at the microsystem level included overwhelming domestic expectations and worry about their own children in the girls’ roles as young mothers. Experiences of intimate partner violence and family conflict were common. At the exosystem level, participants described safety concerns and financial and legal system challenges. The macrosystem level highlighted social expectations around married girls discontinuing education and around separation or divorce. As efforts continue to prevent child marriage within the Syrian crisis and globally, understanding experiences of already married girls is critical to providing support for mitigating harm to child brides. Programs might consider safety planning, parenting supports, access to skills training and education, peer-to-peer social networking, and engaging husbands or families of child brides.

1. Introduction

Since 2011, Syria has experienced a civil war resulting in one of the worst humanitarian and refugee crises in recent history [1]. An estimated 6.45 million people have been displaced within Syria, and another 5 million have fled to other countries—primarily Lebanon, Turkey and Jordan [2]. In 2016, Lebanon was estimated to have a population of 4.5 million, and it was hosting 1.1 million Syrian refugees, making it the highest per capita host of asylum seekers in the world [3]. Most Syrian families in Lebanon live in makeshift structures within informal tented settlements or in overcrowded rental spaces [4]. In 2020, 89% of Syrian refugees in Lebanon were living in extreme poverty [5].

1.1. Impact of Displacement on Child Marriage of Syrian Girls

Child marriage is defined as any formal or informal union where one or both parties is below the age of 18 [6]. Before the war, in 2007, 13% of Syrian girls were married before age 18, but by 2017, this number had increased to 35% [7]. Numerous reports demonstrate an increase in child marriage following migration into Lebanon as well [8,9]. Despite evidence from a national study which concluded that both Syrian women and men respondents viewed child marriage unfavorably [10,11], the practice has been used as a post conflict coping strategy [10,12,13]. Some studies that focused on understanding the perspective of parents revealed gendered differences in parents’ justification of the practice. For mothers, they often associated marrying their young daughter with the need to protect their daughters and their ‘honor’ from being exposed to different forms of sexual and gender-based violence [10,12]. For instance, one study reported that Syrian mothers became more concerned about their daughter after they became exposed to the more liberal Lebanese social norms, worrying that they may end up jeopardizing their ‘honor’ by engaging in premarital sexual activities [14]. Fathers, on the other hand, were more likely to reference financial constraints as the basis to approve child marriage, and they saw in it a relief from the burden of caring for another family member [10,12]. Understanding parents’ perspective is vital since the final decision around marriage is often made by parents, especially male heads of the households [14].

Considerable research has focused on the rates of child marriage and interventions aimed at preventing early unions [7,10,14,15]. Only a few studies focus on understanding the role of the girls in the decision-making process around marriage. These studies homogenously concluded that even though some girls may appear to be active agents in the decision-making process and consenting to marry, they often did so while being heavily influenced by their families’ wishes or by the complexities caused by displacement during humanitarian crises (poor living conditions or lack of alternative opportunities such as education) [10,16].

1.2. Impact of Child Marriage on Adolescent Girls

Child marriage has enormous consequences for adolescent girls and their development. Early marriage greatly limits girls’ access to formal education, limiting their literacy skills and future earning potential [17,18,19]. Girls who marry early have reported higher levels of depression and have an increased risk of somatic illnesses [20]. Child-bearing during adolescence increases the risk of complicated pregnancies and deliveries [21,22,23], and infants born to young mothers are at higher risk for neonatal death, low birth weight, and stillbirth [24,25,26]. Compared to women in their 20s, girls under age 15 are five times more likely to die during childbirth [27]. Girls who marry early are also known to be at higher risk of intimate partner violence in comparison with adult women [28,29]. Finally, child marriage has significant potential to impact children born to women who marry early, thus continuing the cycle of vulnerability [30,31].

1.3. Current Policies and Response to Child Marriage in Lebanon

The issue of child marriage has received considerable attention in Lebanon, including the annual 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence campaign being focused on child marriage in 2019. Marriage in Lebanon requires validation by a religious court (for Muslims) and legal registration. Additionally, the constitution gives religions the ability to manage their own religious laws and there is no civil code which covers all marriages. Fifteen different laws for eighteen different religions list varying ages from which marriage can occur. Culturally, however, marriage is recognized as a contract between the bride and groom, and many Syrian refugees are married in the community without official registration. Several draft laws have been submitted to parliament to change the minimum age of marriage to 18, but as of the time of writing, these laws have not been passed [32].

1.4. Theoretical Framework

This study of child bride lived experiences after marriage is underpinned by socioecological theory. Developmental psychologist Urie Bronfenbrenner is widely recognised for his socioecological theory of adolescent development. Bronfenbrenner hypothesised that, in addition to factors that are associated with the individual (sex, age, health status, etc.), adolescent development is impacted by factors in five environmental systems: the microsystem (family, peers, school, neighbourhood, church, etc.); mesosystem (relationships between microsystems); exosystem (environmental factors, which originate largely beyond the immediate realm of the individual, i.e., mass media, social welfare, legal services, government, etc.); macrosystem (attitudes and ideologies of the culture); and the chronosystem (sociohistorical conditions or patterns of events and transitions over a life course) [33,34,35,36]. A large body of literature exists surrounding this ecological model and its application and evolution since first publication. Socioecological models such as Bronfenbrenner’s describe the interplay of varying system influences on individuals. Bronfenbrenner’s model specifically describes how individuals are linked to a dynamic social system [37], which we centre as critical to the child bride experience. A socioecological understanding of the experiences of Syrian child brides after marriage acknowledges the diverse and layered settings and pathways of influence associated with their lives. This approach helps us describe their experiences in ways that are meaningfully connected to understandings about their development and to appreciate the other people, policies, systems or beliefs which need to be considered when designing interventions to support child brides.

1.5. The Current Study

This study answered the following research question: what are the lived experiences of Syrian child brides in Lebanon, and how do their needs evolve as they navigate their new roles as wives, mothers, and daughters-in-law? The goal of the research was to inform programming and policies that mitigate the risks of child marriage and support child brides. Empirical data on the experiences of child brides is significantly lacking. While several studies have examined the factors influencing the decision to marry early, the needs of child brides after marriage has received disproportionately less attention. To address this gap within the context of the Syrian crisis, we conducted this qualitative analysis of data from a larger 2016 mixed-methods study by thematically analyzing the experiences of child brides after marriage. The themes identified were then organized according to the levels of Bronfenbrenner’s socioecological theory of human development [38] in order to present experiences across all levels of the girls’ interactions and environments.

2. Materials and Methods

This study analyzed data from a larger, cross-sectional, mixed-methods study conducted by the ABAAD Resource Center for Gender Equality and Queen’s University from July to August 2016. The purpose of the original research was to examine the experiences of Syrian girls in Lebanon with a focus on child marriage [10,39]. The current manuscript focuses exclusively on the experiences of married Syrian girls after their marriages.

2.1. Sampling and Recruitment

In the larger 2016 study, a range of participants was included (married and unmarried Syrian girls, Syrian mothers and fathers, husbands of Syrian child brides, unmarried men, and community leaders). All participants were aged 13 or older. A convenience sample of participants was recruited from public spaces such as markets, cafes, and transportation depots in three geographic locations (Beqaa, the greater Beirut area, and Tripoli), with efforts made to recruit a diverse range of backgrounds. For this specific study, only the data from married Syrian girls and parents of Syrian girls were analyzed. There were no other inclusion criteria, and there were no exclusions based on length of time in Lebanon, home region in Syrian, religious affiliation, or other demographic characteristics.

2.2. Interview Team

All data were collected by a team of nine Syrian interviewers (six female, three male) and three male Lebanese interviewers. Interviews were conducted in Arabic in the greater Beirut area, Tripoli, and the Bekaa Valley, Lebanon. All interviewers participated in a four-day training prior to data collection.

2.3. Survey and Interview

Data were collected using Cognitive Edge’s SenseMaker®—a tablet-based data collection tool that helps researchers collect and learn from short narratives that are provided by participants about their experiences on a topic of interest [40] (see Appendix A for narrative prompts). The survey was piloted among 28 participants recruited through the ABAAD Resource Center for Gender Equality across three target locations: Beirut, Beqaa, and Tripoli. Two researchers were present at each interview, one to conduct the interview in Arabic and the other to take notes on the interview process and to record any identified problems. Participants were asked questions regarding opinions on length of the survey, comfort using the tablet, language comprehension, and difficulty responding to the sensemaking questions, with this feedback being used to refine the survey. Full details of the study implementation have been previously described elsewhere [39].

In contrast to typical interviews, a SenseMaker® study includes asking participants to share a story about a given topic using open-ended prompts, in this case asking generally about the experiences of Syrian girls living in Lebanon. In this way, participants are empowered to share experiences which are important and relevant to them, without being led by directed interview questions. With a sensitive topic such as child marriage, direct questioning can lead to defensive answers and social desirability bias [39], but the use of a SenseMaker® approach may help to mitigate these issues. Despite not mentioning or asking about child marriage in the survey or interview, 40% of the participants in the overall study referenced child marriage organically, illustrating how important this topic was to those who participated.

Single-encounter interviews were conducted in person and individually with each participant and lasted approximately 15 min. There was no prior relationship between the interviewers and participants. The story shared in response to the prompt was audio recorded on the tablet within the SenseMaker® software. If participants were uncomfortable having their voice recorded, the interviewer listened to the story in full and then recounted the story in their own voice for the recording (identifying that they were recording on behalf of the participant). After the narrative was recorded, participants used the SenseMaker® software to respond to multiple-choice questions requesting demographic data as well as data to contextualize the story (e.g., who the story was about, how often the events in the story occurred, etc.).

2.4. Ethics

No identifying information was collected, and all interviews were conducted in a private setting. Informed consent was reviewed and indicated by tapping a consent box on the tablet. No monetary or other compensation was offered for participation. The Queen’s University Health Sciences and Affiliated Teaching Hospitals Research Ethics Board approved the study protocol (protocol #6014981).

2.5. Data Analysis

For the larger study, all narratives that were identified by research assistants as being about or mentioning child marriage were transcribed and translated from Arabic to English. For this analysis, we started by examining the narratives shared by married and divorced or separated Syrian girls, as it was critical to understand their personal experiences and own perspectives about married life, and we wanted their voices to be front and center. A decision was subsequently made to also include the narratives from Syrian mothers and fathers. This decision was made because the parents (mothers in particular) shared some of the richest narratives around more sensitive topics, such as intimate partner violence (IPV), which the research team felt were important to include. Furthermore, as older individuals with more lived experiences, the mothers and fathers offered a different reflection on how their daughters were experiencing married life, often contrasting that with their daughters’ lives prior to marriage or observing aspects of interpersonal relationships, household responsibilities, or societal pressures which the girls themselves may not have been aware of. Other categories of participants (married or unmarried men, community leaders) were not included in the analysis, as their narratives typically did not include detailed experiences of married girls themselves and instead usually relayed stories they had heard in their communities rather than personally experienced.

The total number of narratives shared by married and divorced or separated Syrian girls (n = 97) and parents of Syrian girls (n = 53), were screened for inclusion in this analysis. Three researchers (AC, EH, and SH ) independently screened the narratives, selecting those that described the girls’ experiences after they had married. All three reviewers discussed any discrepancies to reach consensus regarding inclusion. In total, 113 narratives which related experiences after marriage were retained for analysis, including 83 from married and divorced or separated Syrian girls and 30 from parents. Because the experiences of Syrian girls in Lebanon and circumstances leading up to marriage have been published elsewhere [10], the focus of the current analysis was therefore exclusively on experiences following marriage.

Using inductive coding, thematic analysis of the included narratives was conducted as described in Braun and Clarke [41]. This process consisted first of a process of familiarization with the data, followed by independent open coding by researchers AC, EH, and SH to generate initial codes. This list of codes was then discussed and defined, sorted into categories, and included in a code book. AC, EH, and SH subsequently coded each narrative utilizing the codes from the code book. Utilizing the integrated calculator for interrater reliability within Dedoose, the pooled Cohen’s kappa was calculated to be 0.72. Excerpts for each code were summarized to allow common themes within the data tagged to each code to emerge. This summary was reviewed by AC, EH, and SH, and potential themes representative of the data were created. All themes were reviewed, and after final themes were defined, they were organized according to the levels of Bronfenbrenner’s socioecological theory of human development [38]. Illustrative quotes were chosen for each theme as presented in the following Section 3.

2.6. Positionality

The researchers recognize their positionality and note that as non-Syrian academics (AC, EH, SH, CD, and SB) and a civil society program manager based in Lebanon at the time of data collection (SM), the results are interpreted with our own biases and perceptions. We realize that our positionality influences our interpretation and representation of the findings and are cognizant that we cannot speak on behalf of Syrian girls. This study was conceptualized after completing the original analysis of the larger SenseMaker® data when numerous striking narratives describing both positive and negative experiences following marriage from Syrian child brides were noted. The authors believed that their voices ought to be shared given how few data currently exist regarding the experiences of girls after child marriage. While the ultimate goal would be to reduce and eliminate child marriage, we hope the current study can be utilized to inform approaches to minimize the negative impact on those who are child brides.

3. Results

In total, 113 narratives were retained for analysis, including 83 from Syrian girls and 30 from parents. Participant demographics are included in Table 1. As shown, most Syrian girl participants were currently married (84%) or had been married and were divorced/separated at the time of the survey (13%) and were aged either 13 to 17 (67%) or 18 to 24 (32%). Fifty-nine percent of the girls reported also being a mother. Of parents sharing narratives about the lived experiences of Syrian child brides, 87% were mothers and 13% were fathers who told stories about their married daughters. Emerging themes about the lived experiences of child brides are summarized in Figure 1 and presented by level of Bronfenbrenner’s socioecological theory of human development.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics.

Figure 1.

Bronfenbrenner Socioecological Theory Adapted for Lived Experiences of Child Brides.

3.1. Microsystem

The microsystem for an adolescent includes interpersonal relationships experienced within their immediate environment [38]. Syrian girls described a wide range of negative and positive experiences. The themes which emerged at this level were the experiences arising from interpersonal relationships created by the girls’ new social roles. The microsystem level also included the themes of IPV and domestic violence (DV). Conversely, some girls shared positive experiences and described being happy in their marriages.

3.1.1. Change in Social Role: Experiences as Wives

This theme focused on Syrian girls’ experiences navigating the relationship with their husbands and managing a household. The most common experience shared was the stressful or overwhelming expectations for child brides and concerns regarding their new domestic roles. Following marriage, young Syrian girls are often faced with overwhelming marital duties. One mother living in Beqaa described her 16-year-old daughter’s situation:

She was very happy during the first two months and a half of their marriage… Even though I told her husband that my daughter doesn’t know anything about managing a household since she is very young, and she didn’t have the chance yet to learn, he said that it is not a problem, and that he will teach her. But, when his mother visited them, she criticized her… My daughter has been spending her days at my house, and she would return to her home at 11:00 p.m. and go directly to sleep. This started a huge fight with her husband. After her mother-in-law left, we talked to her husband. I told him, I told you that my daughter is still very young, and she doesn’t know how to manage a household.(ID765)

Another girl described her own experience, reporting that there were a lot of problems when she first married. At the age of 15, she did not know how to cook or do house chores which were expected of her (ID1413). Speaking of a girl who married at age 14 and had a child at age 15, another participant said that ‘[she] has lost her childhood, and now she has overwhelming responsibilities’ (ID190).

3.1.2. Change in Social Role: Experiences as Mothers

This theme included any narratives which described child brides’ experiences with pregnancy, being mothers, and caring for their children. Eighteen different narratives shared experiences of significant concerns for their children. Though still adolescents themselves, the girls worried about their own children: getting them registered, educating them, supporting them financially, and taking care of their basic and medical needs.

Like many mothers, the girls wanted their children to have a better life than their own:

I wish I could have continued school but I didn’t have the chance. That is why now I put a lot of effort into my children’s education; I want them to be educated. I do not want my children to go through what I had to go through. I’d like for them to go out a lot, to be educated, and to have a social life.(ID648)

One story put it simply:

Now, she’s a child, and she has a child.(ID22)

3.1.3. Positive Experiences with Marriage

Although many stories discussed negative experiences with marriage, some participants (33 narratives) shared positive aspects such as happiness, safety, or an improved quality of life. The following 17-year-old Syrian girl described a happy marriage:

I wasn’t forced to marry my current husband. I wanted to get married, and I am happily married. I have a child, and I am very happy. My husband and I love each other. My husband is working and supporting us. I do the house chores, and I can go out and do whatever I want to do.(ID436)

In several other cases, getting married allowed girls to escape traumatic situations as was the case for this participant who was harassed by the principal at her school:

I was relieved after I got married. I was relieved from men’s harassment. I preferred to get married.(ID699)

Other girls describe being more content in their marriage than they were living with their families:

I am more comfortable with my husband than with my parents. My parents used to force me to work a lot. With my husband I am very happy. My child and I do not need anything. My husband works in anything, and he spends his salary on our needs.(ID1414)

3.1.4. Experiences with IPV and DV

A large number of stories described girls’ experiences of IPV after marriage. This included physical, sexual, financial, and verbal abuse as well as restricted movement and limited freedoms. Twenty-three narratives referenced some form of physical violence after marriage. Some girls described enduring IPV for the sake of their children, as in this case where one girl who said, ‘I endured our abusive relationship for two years. I was patient for my daughter’s sake’ (ID432). Similarly, another participant reported:

First, I have been married for four years. I have never lived a happy day with my husband. My daughters are the reason behind my patience…I am enduring all of this for my daughters’ sake.(ID458)

In contrast, some girls left abusive marriages and returned to their family homes. Even there, some continued to experience abusive or controlling treatment by their ex-husbands or their own families. One girl shared:

I was being abused daily, physically and sexually. Now, I ran away to my relative’s house. However, my family is a clan, so I don’t have the freedom to go out of the house. In addition, my husband is a member in some political party; so, he is using his political power to pressure my relatives to keep me imprisoned in the house.(ID237)

IPV frequently extended to additional domestic violence (DV), with other family members abusing child brides as well. This girl experienced physical and verbal abuse from several people:

My husband, his mother and his uncle beat me. Even their guests would beat me. I neither ate nor drank anything and I always stayed alone. They would yell at me and insult me all the time.(ID1320)

Experiences of IPV and DV had severe psychological and physical consequences. For instance, one girl spoke of a suicide attempt, stating ‘I suffered a lot. I tried to kill myself’ (ID1314), while another described how the violence caused a miscarriage:

I suffered in this marriage. I was pregnant, and in my 7th month I bled because he hit me, and I miscarried the child. I wanted to get a divorce, but I couldn’t.(ID 461)

Lastly, in some cases, violence also included children in the household. One participant explained:

After they got married, he [the husband] changed. He started to beat her and insult her. She gave birth to a little boy, so he started to beat both, his wife and his child.(ID241)

3.1.5. Change in Social Role: Experiences as Daughters and Daughters-in-Law

This theme includes the narratives about the girls’ relationships with their own families and their husbands’ families (usually parents or parents-in-law, but additional family relationships were also included within this theme). Some depended on their own mothers to help them with the overwhelming responsibilities of being a wife and mother. Others experienced significant conflict with their families. Several of these conflicts occurred when turning to their families for support in the context of being in an unhappy or abusive marriage. One participant’s escape from IPV led to conflict with her own parents and more physical violence.

I stayed there for 20 days, and I couldn’t take it anymore. I returned to my parents’ house, and they told me that everything will be okay after my husband and I reconcile. When I told them I do not wish to reconcile things with my husband, they started to beat me as well.(ID1320)

Relationships with in-laws were typically challenging for the married girls. In fact, there was only one positive experience shared about the husband’s family. In that particular case, the girl reported preferring to live with her parents-in-law, because she did not like her husband. All other participants described conflict or difficulties with their husband’s family. One experience is described below:

I lived at his parent’s place, and his sisters-in-laws were so mean to me. I was the youngest, so I couldn’t tell them anything. I had to obey whatever they asked me to do. They accused me of wrongful things that I never did. I do not know why they did that.(ID458)

3.2. Exosystem

The exosystem for a developing adolescent includes elements of the microsystem which influence the individual indirectly. For example, this includes factors related to neighborhoods, parent’s workplaces, or family friends. Themes in this system included experiences with lack of safety, financial challenges, limited work opportunities, and challenges with the legal system.

3.2.1. Experiences with Lack of Safety

This theme included narratives which spoke about the girls’ experiences or concerns about safety and security living in Lebanon. Many narratives described that it was not safe to go outside or walk around. Fear of harassment was equally shared between girls regardless of their marital status or having children:

When I go to Beirut, the taxi drivers would harass and catcall any women passing by. Regardless if the woman was with her child, married, or pregnant; they would harass any woman.(ID906)

And here in the camp there is no safety, after it’s dark we can’t go out, and I’m under 18 years, and if whatever happened to my kids, even if my kid dies, I can’t go out before my husband is back. I don’t feel safe going out alone, after it is dark there is no safety.(ID253)

3.2.2. Experiences with Financial Challenges and Work Opportunities

Narratives which spoke about money, finances, poverty, or work opportunities were included in this theme. Concern regarding finances were mentioned in 40 different stories. Some participants did not have enough money or support for regular meals. This was also mentioned in the context of the husband controlling the finances and the wife not having access to enough food.

We used to receive help in the beginning but they stopped. There is the burden of house rent. The most thing I worry about is the house rent. I don’t have money to renew my papers. I don’t have money to register my children. We barely pay rent and buy food.(ID1240)

Several other narratives (20 stories) referenced married girls having to work in order to support themselves and their families. One participant stated, ‘In order to survive, we stopped going to school and we started to work’ (ID1415). Many stories described girls selling gum/tissues or other small items in the streets. Other narratives described difficulty or inability to find work. One participant stated her husband prohibited her from working saying, ‘I want to be able to provide some of my children’s needs, but he refuses.’ (ID361) Two stories indicated that a woman could not work because she was pregnant.

3.2.3. Experiences with the Legal System

This theme encompassed experiences dealing with registration, obtaining documents, restricted mobility, or regulatory and legal bodies. Participants described significant stress related to documentation and registration. For instance, 22 of the participants discussed not having legal documentation for their marriages and/or worries about registering their children.

I have two children, I delivered the girl in Lebanon… When they started giving cards, they didn’t give me one, and said I didn’t deserve it. I didn’t receive any help… I’m living illegally here. I went back to the UN and they sent me to a lawyer, but he didn’t help.(ID1168)

The lack of documentation often led to additional financial stress and worries about future challenges that may arise if they lacked these legal documents. Financial and legal difficulties also interfered with the girls’ ability to see their own families. Often participants described that they could not return to Syria to renew papers because their current papers had expired. These complications led to a cycle of barriers that were difficult to overcome.

I wish I can see my parents but I can’t, because I broke my residency and I need renewal and a sponsor. Even if I went to Syria, I need a sponsor and an order or I can’t go. Even if I found a sponsor, I need a lot of money for renewal, and I don’t have money. Even if I got the money I can’t go because I need a guardian or they won’t let me pass, because I’m under the 18 years.(ID692)

Being estranged from their families would be particularly challenging when dealing with overwhelming responsibilities, new motherhood, or navigating new family dynamics.

3.3. Macrosystem

The macrosystem consists of cultural, societal, and political contexts and values that can influence a society as a whole, including the child brides. The main themes emerging in this category were experiences with societal expectations around continuing education and the ability to get a divorce.

3.3.1. Societal Expectations: Continuing Education

This theme examined experiences shared regarding attending or not attending school once the girls were married. One participant spoke clearly about the societal expectations that married girls have to stay at home, and she emphasized that this was even more true in Lebanon. In fact, many girls spoke about not having the option to continue with school after marriage, and one girl stated simply, ‘I have lost all hope of continuing my education.’ (ID455) Another girl expressed her ongoing aspirations to be educated after indicating that she had wanted to be a doctor. However, she was resigned to the fact that this was no longer a possibility after marriage, while appealing to other parents to prioritize education for their children.

I got married once I had the chance to. I am happily married, thank god. I still dream of continuing my education, even though I know I never will. I wish for every girl my age to be able to go to school, and I wish from the Lebanese government to give a certification to every Syrian student. I wish from every mother to aid her children in pursuing their education.

In total, 49 girls spoke about education in the stories they told. Out of these, only two girls specifically reported that they were able to continue to go to school after marriage. It is worth noting that this was made possible because the husband permitted it.

For a while, she was frustrated, and she felt that everything changed. Now, she is happy. Her husband is a nice person, and he gives her all the freedom she needs. He didn’t prohibit her from school.(ID740)

3.3.2. Societal Expectations: Divorce

The final theme examined narratives which spoke about divorce, separation, living separately, or relationships with ex-partners. Social-cultural conflict arose with regards to divorce and separation. Twenty-five of the shared narratives spoke about experiences with divorce or separation. Several girls reported wanting to get a divorce but being unable to due to the husband’s or family’s wishes, while others accounted experiences with their husband wanting a separation or divorce soon after the initial union.

Finally at the court my husband told me “I no longer want you” and that was when I fainted and I couldn’t take it anymore…I hated him for making me so attached to him then throwing me away like that.(ID1417)

In contrast, some partners threatened to take away a child if the girl was to leave the marriage, sometimes carrying through with the threat since it is allowable under existing laws.

I had a daughter, and he still beats me. I couldn’t endure the situation anymore, and I wanted to go back to my parent’s house. He divorced me, and he took my daughter.(ID432)

4. Discussion

Although there has been recent research demonstrating increased rates of child marriage during the Syrian crisis [7,15], there has been little written regarding the lived experiences of the girls following these marriages. Using data from Syrian girls and their parents, we present an analysis of the experiences of child brides organized using Bronfenbrenner’s socioecological theory of human development to inform policies and programming that will better support them.

One theme which emerged at the microsystem level was child brides facing overwhelming responsibilities as wives and mothers. This concept is mentioned briefly in one previous study of experiences of married girls in Bangladesh [42]. Our study significantly adds evidence to support this, as it played a particularly prominent role in the lived experiences of girls who participated. Married at very young ages, the girls were suddenly expected to manage households, bear and raise children, and sometimes support the family financially. These responsibilities led to conflicts with husbands, in-laws, or the girls’ own families and negatively impacted the girls’ well-being. Child brides also worried about providing for their children and about their children’s education. It is important to note that the girls in our study faced these challenges on top of their status as refugees, which can further exacerbate their responsibilities, isolation from family, and ability to navigate a new country and system. These perspectives from child brides who are additionally facing the challenges of displacement expand on previous literature focused on child brides in their home settings. Programming to help girls learn to manage a household, care for children, and how to access children’s education would provide much-needed support for these young wives and mothers. While some life skills programming does exist, it has been noted that it is not necessarily developed for or targeted towards married girls [32]. Further study on whether these existing programs actually alleviate the challenges experienced by married girls would also help guide best practices and policies.

Furthermore, at the microsystem level, experiences of IPV and DV were very common, not only between child brides and their husbands but also with in-laws or members of their own families. Previous studies have shown that girls who marry early are at higher risk of experiencing intimate partner violence [28,29]. This study supports these findings with many reports of lived experiences of Syrian girls experiencing IPV. The narratives expand on these findings by providing context for the types and range of violence that child brides experience after marriage (physical, emotional, financial, and restriction of freedoms). Participants also describe being manipulated to remain in abusive situations due to threats around losing their children. This highlights the importance of increasing education and support services to Syrian girls and their families. Importantly, when child marriage does occur, programs must work to provide confidential support to married girls and their children while working with boys and men to educate and prevent IPV within marriages.

Previous studies have found that child marriage is frequently used as a way to escape from or cope with poverty [10,12,42]. The current study adds to the literature by finding that child brides frequently continued to face financial strain after marriage. They also faced challenges with the legal and registration systems for refugees in Lebanon. These elements of the exosystem compounded the more immediate worries, impacting the girls’ ability to access basic needs, enroll themselves or children in school, or maintain contact with their family. Marriage registration is incredibly complex, requiring multiple documents, letters from officials, blood tests and fees—and children cannot be registered unless their parents’ marriage is registered [32,43]. One report showed that out of a total of 1702 refugees who were able to obtain a marriage contract in Lebanon, only 15 were successfully able to navigate all the steps to obtain a final registration [43]. Simplified registration protocols or improved access to registration, as well as financial or legal support, would help child brides and their families navigate these systems.

With respect to exosystem factors, our results also showed that child brides were significantly constrained by feelings of a lack of safety to move about freely in Lebanon. As a result, many child brides faced significant isolation. This suggests that girls may find it difficult to safely or freely attend even the most inclusive programming, and consideration should be given to possibilities such as mobile outreach and social media or online support, which girls could access safely or privately from their homes.

At the macrosystem level of Bronfenbrenner’s model, difficulties around divorce or leaving a marriage were frequently described. It has been reported that divorce can add to both social and psychological pressures as adolescents then carry the ‘divorced’ label at young ages [44]. In Lebanon, there is presently no unified legal minimum age to marry. Marriage and family life are governed by personal status laws. Article 9 of the constitution grants religious authorities the ability to establish personal status laws within a community [45]. The previously mentioned complications of registering a marriage also further complicate a divorce, as without a registered marriage, girls cannot access courts and legal protections during divorce proceedings [32]. To prevent early marriage and grant women rights to divorce, working with both civil and religious leaders within communities is imperative.

Other societal expectations of married women prohibited many of the girls from continuing their own education, which has been shown to limit literacy skills and future earning potential [17,18,19]. A previous study in Jordan identified that although it is not a law, there is an accepted ‘norm’ that prevents married girls from returning to school [44]. This was supported by many narratives in this study describing girls’ desire to attend school but being unable to do so after marriage. Several stories convey a complete lack of hope that they would ever be able to access education. As it is well known that education is essential for breaking the cycle of poverty and elevating the situation of women and girls [19], providing opportunities for child brides to continue attending school, even in situations of displacement and even after they marry, is critical. There should be a priority on programming which provides targeted education, literacy training, or trade skills to help child brides obtain employment and improve their financial stability.

Perhaps most importantly, a program which aims to target any of the above supports for child brides would also provide the opportunity for girls to meet a circle of peers who are experiencing similar situations. Given the concerns around safety in Lebanon, as well as the social isolation described after marriage, a peer program would provide the opportunity of a safe meeting place (in person or virtually) where girls could not only benefit from programming directly but also develop friendships and support systems among other Syrian girls.

Examining the child brides’ experiences using Bronfenbrenner’s socioecological model of human development helps us to identify that there are factors influencing child brides from micro all the way to macro levels. A comprehensive approach to the support of child brides, and also to the prevention of child marriage, would therefore address barriers and augment facilitators across these levels. This requires focus, for example, on societal norms, the influence of neighborhood factors, the roles of immediate family members, and access to opportunities and support for the individual girl. Syrian child brides in Lebanon are simultaneously forced migrants as well as adolescents who are still in development themselves. Many of these young women are new mothers as well. While some programming has been developed, child brides are a particularly difficult to reach and unique subpopulation of women, and there remain many possible avenues for further supporting them.

This study has several limitations. First, although considerable effort was made to collect narratives from a wide range of participants, the sample was not representative, and thus the results are not generalizable. Girls younger than 13 were not enrolled, and extremely marginalized families may have been underrepresented. As the goal of this study was to understand the experiences of Syrian child brides living in Lebanon, the results of this study cannot be generalized to all child brides or those with different backgrounds, cultures, or socioeconomic status. Original data were collected in 2016 and therefore may not be representative of the experiences of Syrian child brides in Lebanon today. We did not collect data about individuals who declined to participate and so cannot comment on demographic differences between those who participated and those who did not. Second, SenseMaker® narratives are generally shorter and may lack the detail of traditional qualitative interviews. Third, the study cannot speak to the prevalence of certain types of experiences. Although the majority of the stories were negative, this could relate to more memorable or striking stories rather than more prevalent.

There are also several notable strengths. The broader study from which these child brides’ experiences were drawn focused more generally on the experiences of Syrian girls in Lebanon. The open-ended questions allowed participants to tell a story which held importance to them, and the number of narratives which organically referenced child marriage illustrates the importance of this phenomenon within the population. Additionally, direct questioning about child, early, or forced marriage was avoided, allowing the experiences of child brides to emerge from the broader experiences of Syrian girls.

5. Conclusions

This research examines the experiences of Syrian girls who experienced child marriage. As efforts continue to address and prevent child marriage globally and within the Syrian crisis more specifically, understanding these experiences of child brides can inform programming to support those who are already married. Programs may consider supports which mitigate some of the difficulties experienced by Syrian child brides which were identified in this analysis. These could include supports for managing a household; caring for children; dealing with financial, legal, or registration systems; and IPV/DV supports. Programs supporting girls to access or continue education even after marriage would also be beneficial. Future interventions should consider a comprehensive strategy to address the diverse challenges faced by child brides at the different levels of Bronfenbrenner’s model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A.B. and A.C.; methodology, S.A.B., A.C. and C.M.D.; formal analysis, A.C., S.H. and E.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.; writing—review and editing, S.A.B., A.C., S.H., E.H., C.M.D. and S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Sexual Violence Research Initiative and the World Bank Group’s Development Marketplace for innovation on GBV prevention (in Memory of Hannah Graham). Principal investigator, S. Bartels.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of The Queen’s University Health Sciences and Affiliated Teaching Hospitals Research Ethics Board approved the study protocol (protocol #6014981).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. Narrative Prompts for SenseMaker® Survey

Table A1.

Narrative Prompts for SenseMaker® Survey.

Table A1.

Narrative Prompts for SenseMaker® Survey.

| Suppose a family is coming to Lebanon from Syria, and the family has girls under the age of 18. Tell a story about a Syrian girl in Lebanon that the family can learn from. |

| Tell a story about a situation that you heard about or experienced that illustrates the best or worse thing about the life of a Syrian girl (under the age of 18) in Lebanon. |

| Provide a story that illustrates the biggest difference between life for Syrian girls (under the age of 18) living in Lebanon in comparison to life for Syrian girls in Syria. |

References

- United Nations High Committee for Refugees. UNHCR—Syria Conflict at 5 Years: The Biggest Refugee and Displacement Crisis of Our Time Demands a Huge Surge in Solidarity; UNHCR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/afr/news/press/2016/3/56e6e3249/syria-conflict-5-years-biggest-refugee-displacement-crisis-time-demands.html (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. UNHCR—Syria Emergency; UNHCR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/syria-emergency.html (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Adaku, A.; Okello, J.; Lowry, B.; Kane, J.C.; Alderman, S.; Musisi, S.; Tol, W.A. Mental Health and Psychosocial Support for South Sudanese Refugees in Northern Uganda: A Needs and Resource Assessment. Confl. Health 2016, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Communities—Partners for Good. Syrian Refugee Crisis—Global Communities Rapid Needs Assessment; Global Communities: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2013; Available online: https://www.alnap.org/help-library/syrian-refugee-crisis-global-communities-rapid-needs-assessment-lebanon-0 (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- World Food Programme. Nine Out of Ten SYRIAN Refugee Families in Lebanon Are Now Living in Extreme Poverty, UN Study Says. Available online: https://www.wfp.org/news/nine-out-ten-syrian-refugee-families-lebanon-are-now-living-extreme-poverty-un-study-says (accessed on 16 March 2021).

- UNICEF. Child Marriage: Child Protection from Violence, Exploitation and Abuse; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/protection/child-marriage (accessed on 16 March 2021).

- United Nations Population Fund. New Study Finds Child Marriage Rising among Most Vulnerable Syrian Refugees; UNFPA: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/news/new-study-finds-child-marriage-rising-among-most-vulnerable-syrian-refugees#:~:text (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Abdulrahim, S.; DeJong, J.; Mourtada, R.; Zurayk, H. Estimates of Early Marriage among Syrian Refugees in Lebanon in 2016 Compared to Syria Pre-2011. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 27 (Suppl. S3), 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. The Syrian Arab Republic Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bartels, S.A.; Micheal, S.; Rouptez, S.; Garbern, S.; Kilzar, L.; Bergquist, H.; Bakhache, N.; Davison, C.; Bunting, A. Making Sense of Child, Early and Forced Marriage among Syrian Refugee Girls: A Mixed Methods Study in Lebanon. BMJ Glob. Health 2018, 3, e000509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael, S.; Roupetz, S.; Bartels, S. Caught in Contradiction: Making Sense of Child Marriage among Syrian Refugees in Lebanon; ABAAD Resource Centre for Gender Equality: Beirut, Lebanon, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- El-Masri, R.; Harvey, C.; Garwood, R. Shifting Sands Changing Gender Roles among Refugees in Lebanon; ABAAD Resource Centre for Gender Equality and Oxfam GB: Beirut, Lebanon, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson, A. Understanding the Social Processes Underpinning Child Marriage: Impact of Protracted Displacement in Jordan; Terre des Hommes: Cologny, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mourtada, R.; Schlecht, J.; Dejong, J. A Qualitative Study Exploring Child Marriage Practices among Syrian Conflict-Affected Populations in Lebanon. Confl. Health 2017, 11, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulrahim, S.; DeLong, J.; Mourtade, R.; Zurayk, H.; Sbeity, F. The Prevalence of Early Marriage and Its Key Determinants among Syrian Refugee Girls/Women: The 2016 Bekka Study, Lebanon; AUB, UNFPA and SAWA for Development & Aid: Beirut, Lebanon, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Knox, S.E. How They See It: Young Women’s Views on Early Marriage in a Post-Conflict Setting. Reprod. Health Matters 2017, 25, S96–S106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, M.C.; Wodon, Q. Impact of Child Marriage on Literacy and Education Attainment in Africa; Global Partnership for Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; Available online: https://www.allinschool.org/media/1956/file/Paper-OOSCI-Child-Marriage-Literacy-Education-2014-en.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Chaaban, J.; Cunningham, W. Measuring the Economic Gain of Investing in Girls The Girl Effect Dividend; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Available online: http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/730721468326167343/pdf/WPS5753.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Parsons, J.; Edmeades, J.; Kes, A.; Petroni, S.; Sexton, M.; Wodon, Q. Economic Impacts of Child Marriage: A Review of the Literature. Rev. Faith Int. Aff. 2015, 13, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezgin, A.U.; Punamäki, R.L. Impacts of Early Marriage and Adolescent Pregnancy on Mental and Somatic Health: The Role of Partner Violence. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2019, 23, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nour, N.M. Health Consequences of Child Marriage in Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 1644–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annan, K.A. We the Children: Meeting the Promises of the World Summit for Children; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2001; Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/458923?ln=en (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Girls Not Brides. Child Marriage Around the World. Available online: https://www.girlsnotbrides.org/ (accessed on 16 March 2021).

- UN Women. Gender-Based Violence and Child Protection among Syrian Refugees in Jordan, with a Focus on Early Marriage; UN Women: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Available online: https://jordan.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2013/7/gender-based-violence-and-child-protection-among-syrian-refugees-in-jordan (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Save the Children. Too Young to Wed: The Growing Problem of Child Marriage among Syrian Girls in Jordan; Save the Children: London, UK, 2014; Available online: https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/library/too-young-wed-growing-problem-child-marriage-among-syrian-girls-jordan (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Ouattara, M.; Sen, P.; Thomson, M. Forced Marriage, Forced Sex: The Perils of Childhood for Girls. Gend. Dev. 1998, 6, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Women’s Health Coalition. The Facts on Child Marriage. Available online: https://iwhc.org/resources/facts-child-marriage/ (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- United Nations Population Fund. Marrying Too Young: End Child Marriage; UNFPA: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/MarryingTooYoung.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Kidman, R. Child Marriage and Intimate Partner Violence: A Comparative Study of 34 Countries. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 662–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhia, A.; Drolette, L.M.; Vander Stoep, A.; Valencia, E.J.; Kernic, M.A. The Impact of Exposure to Parental Intimate Partner Violence on Adolescent Precocious Transitions to Adulthood. J. Adolesc. 2019, 77, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia. The Challenges for Development in Current Conflict Settings: The Impact of Conflict on Child Marriage and Adolescent Fertility; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson, A. Mapping Responses to Child Marriage in Lebanon: Reflections from Practitioners and Policymakers; Terre des Hommes: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecology of the Family as a Context for Human Development. Research Perspectives. Dev. Psychol. 1986, 22, 723–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Developmental Ecology Through Space and Time: A Future Perspective. In Examining Lives in Context: Perspectives on the Ecology of Human Development; Moen, P., Elder, G., Luscher, K., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological Systems Theory. In Encyclopedia of Psychology; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Morris, P. The Ecology of Developmental Processes. In Handbook of Child Psychology; Damon, W., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Schensul, J.J.; Trickett, E. Introduction to Multi-Level Community Based Culturally Situated Interventions. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2009, 43, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological Models of Human Development. In International Encyclopedia of Education; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 1994; Volume 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhache, N.; Michael, S.; Roupetz, S.; Garbern, S.; Bergquist, H.; Davison, C.; Bartels, S.; Bakhache, A.N.; Michael, S.; Roupetz, S.; et al. Implementation of a Sensemaker Research Project among Syrian Refugees in Lebanon. Glob. Health Action 2017, 10, 1362792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cognitive Edge. SenseMaker. Available online: https://thecynefin.co/sensemaker/ (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crivello, G.; Mann, G. (Eds.) Dreaming of a Better Life Child Marriage Through Adolescent Eyes; Young Lives: Oxford, UK; International Development Research Centre: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC). Update on Marriage Registration for Refugees from Syria; NRC: Beirut, Lebanon, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Higher Population Council. Policy Brief: Child Marriage in Jordan; NRC: Beirut, Lebanon, 2017; Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/jordan/policy-brief-child-marriage-jordan-2017 (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Report on Child Marriage, Early Marriage and Forced Marriage in Lebanon; UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights: Beirut, Lebanon, 2018; Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Women/WRGS/ForcedMarriage71-175/Lebanon.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).