Characterization of Volatile Compounds in Amarillo, Ariana, Cascade, Centennial, and El Dorado Hops Using HS-SPME/GC-MS

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

2.2. Instrumentation

2.3. Volatile Compounds Identification and Statistical Analysis

2.4. Database Software Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Classification by PLS-DA

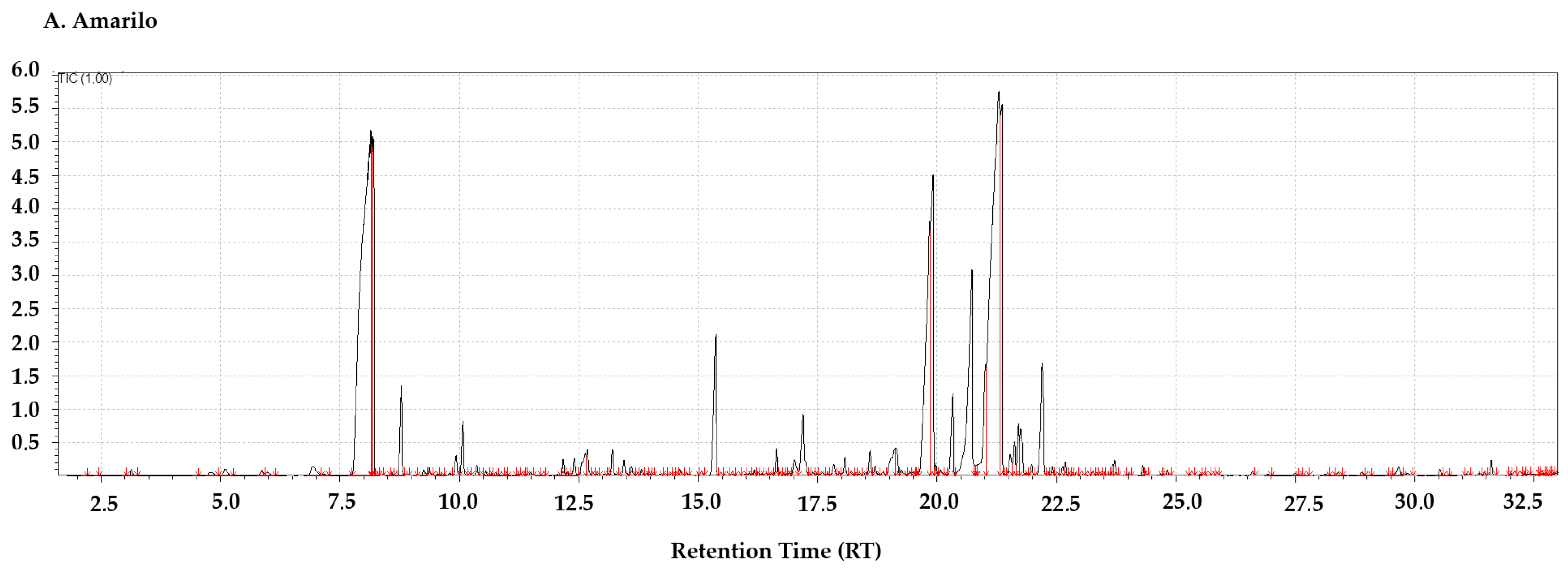

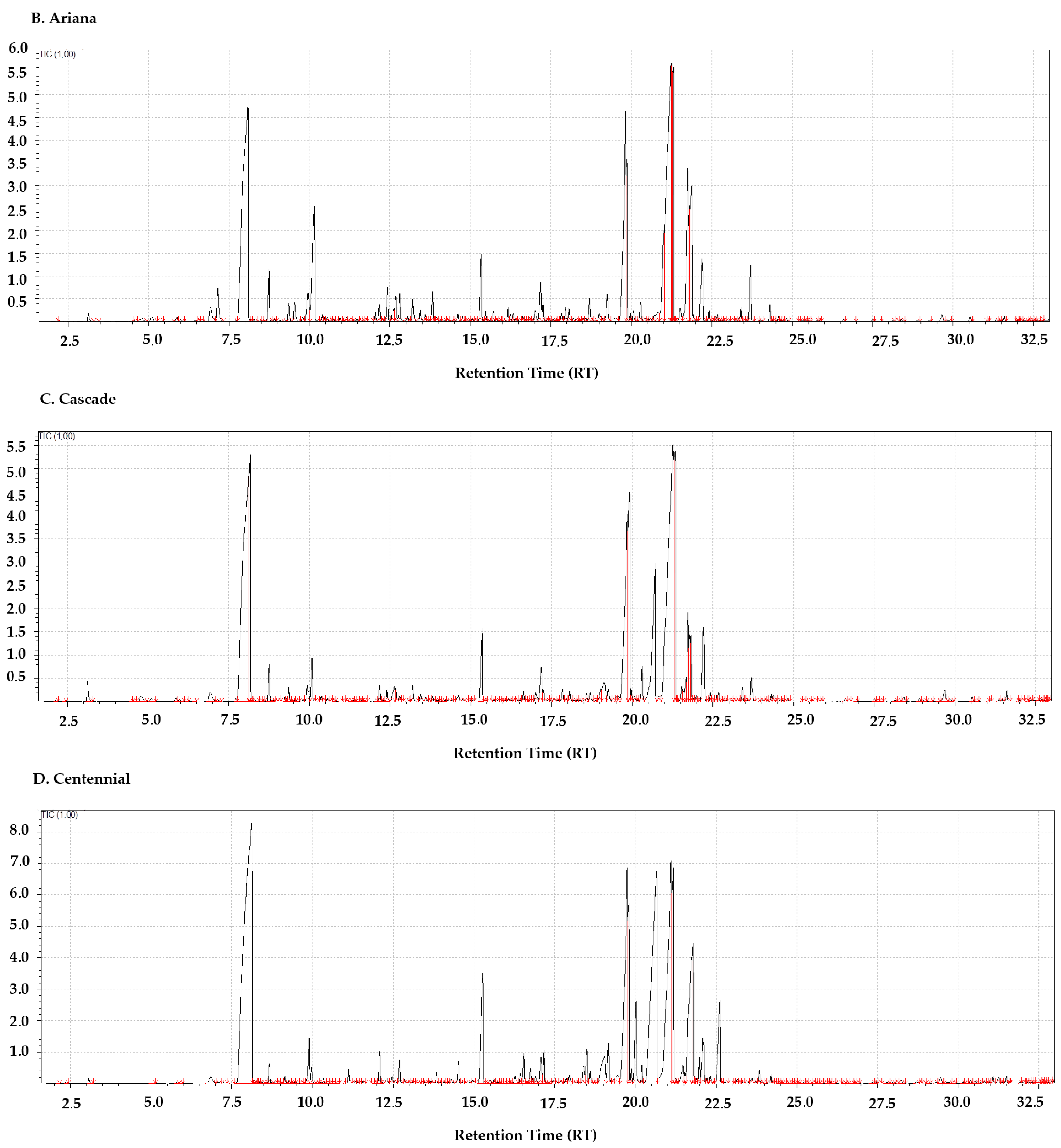

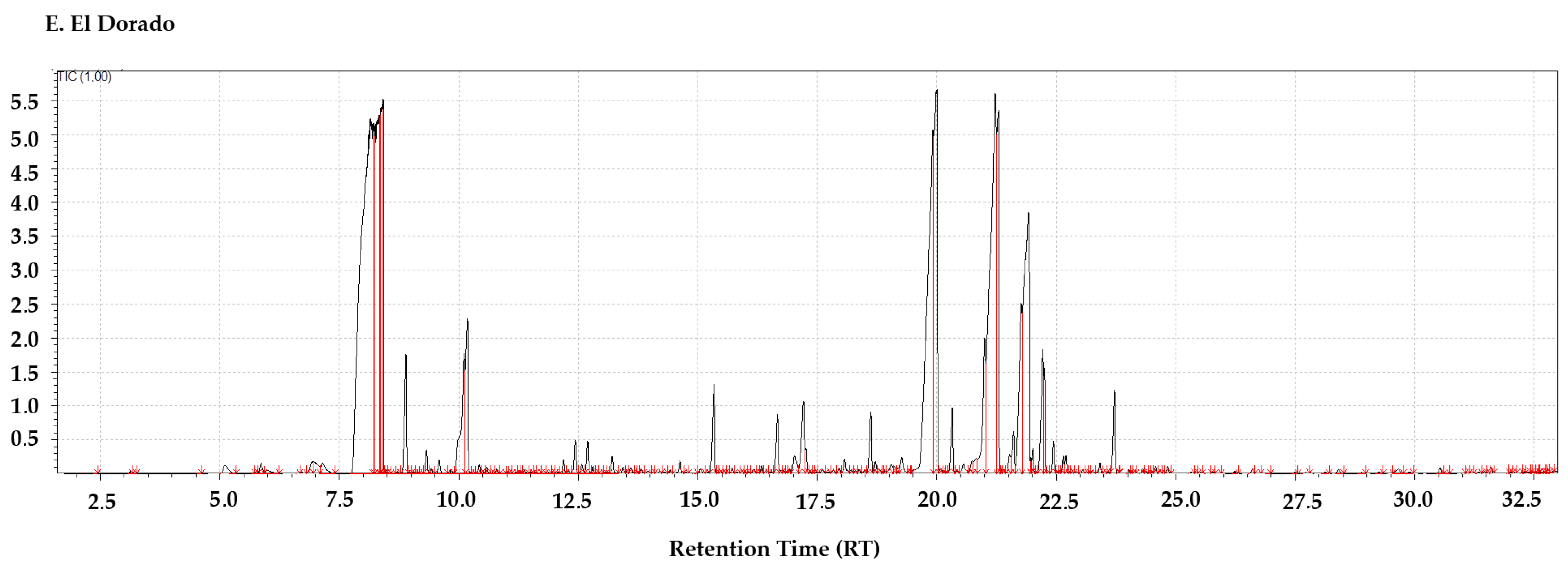

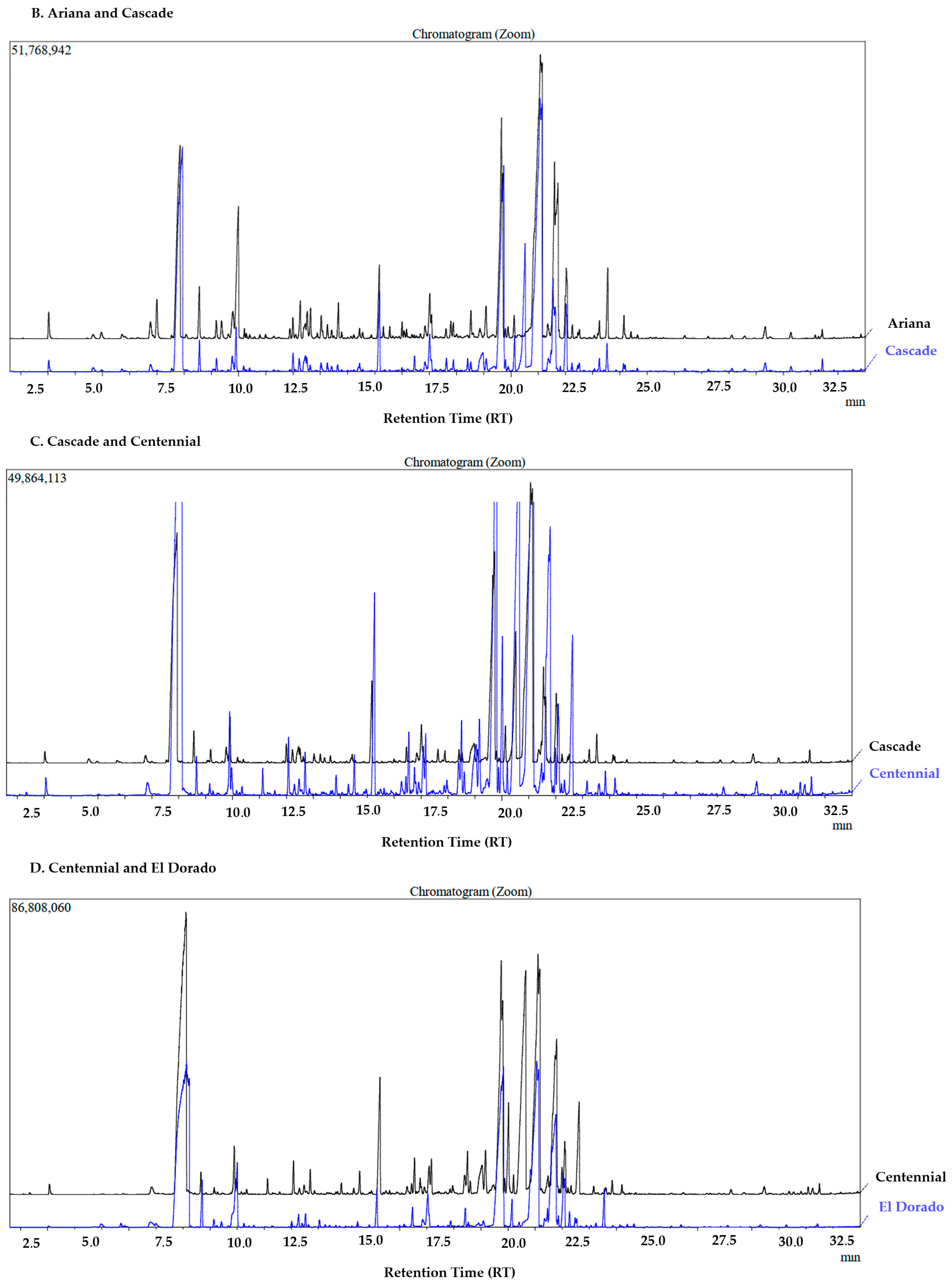

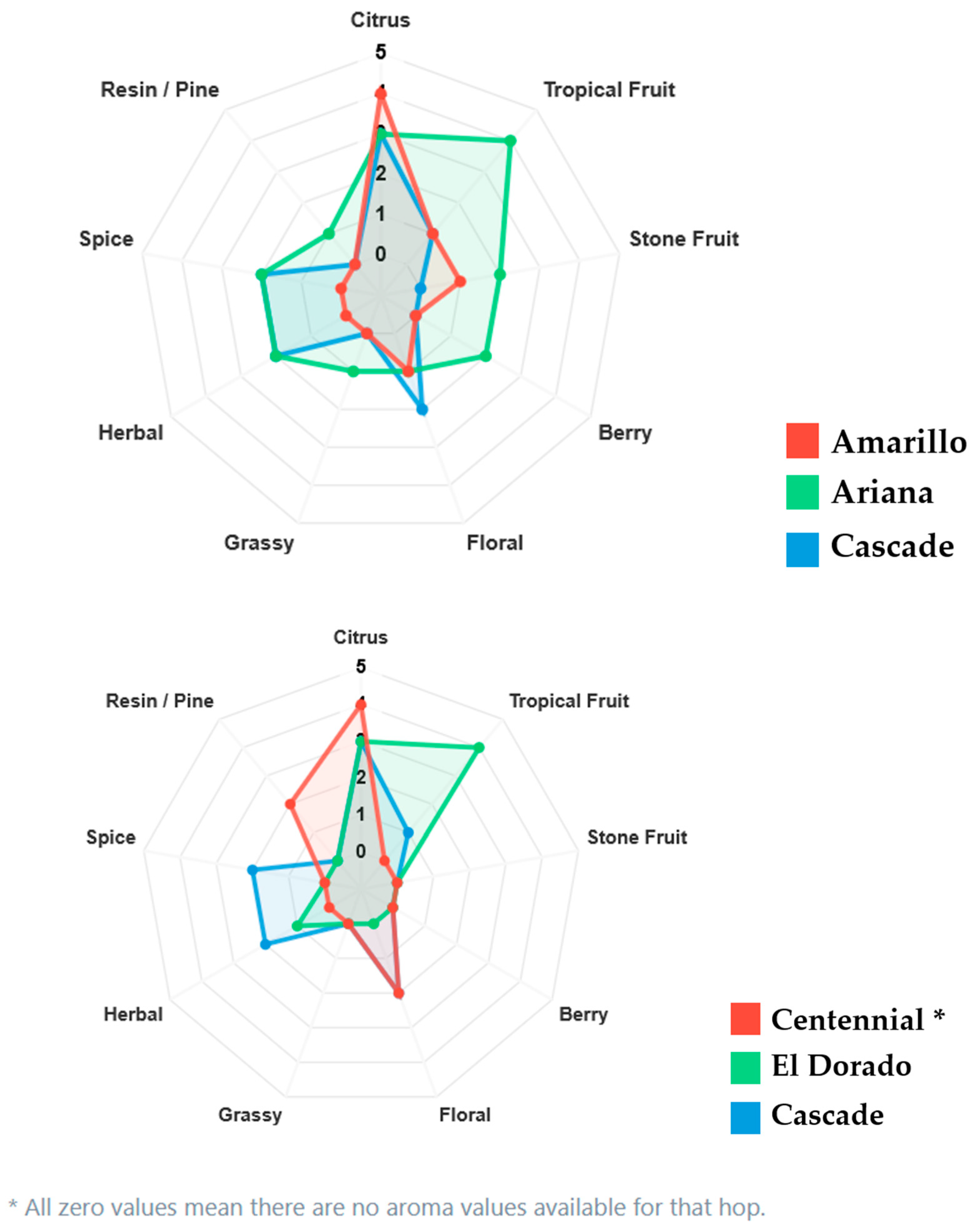

3.2. Aromatic Hop Profile

3.3. Amarillo: Fruity-Floral Complexity with Resinous Depth

3.4. Ariana: Resinous and Fruity with Herbal Nuances

3.5. Cascade: Citrus–Resinous and Bioactive Potential

3.6. Centennial: The “Super Cascade” with Strong Resinous Character

3.7. El Dorado: Intensely Fruity with Tropical Dominance

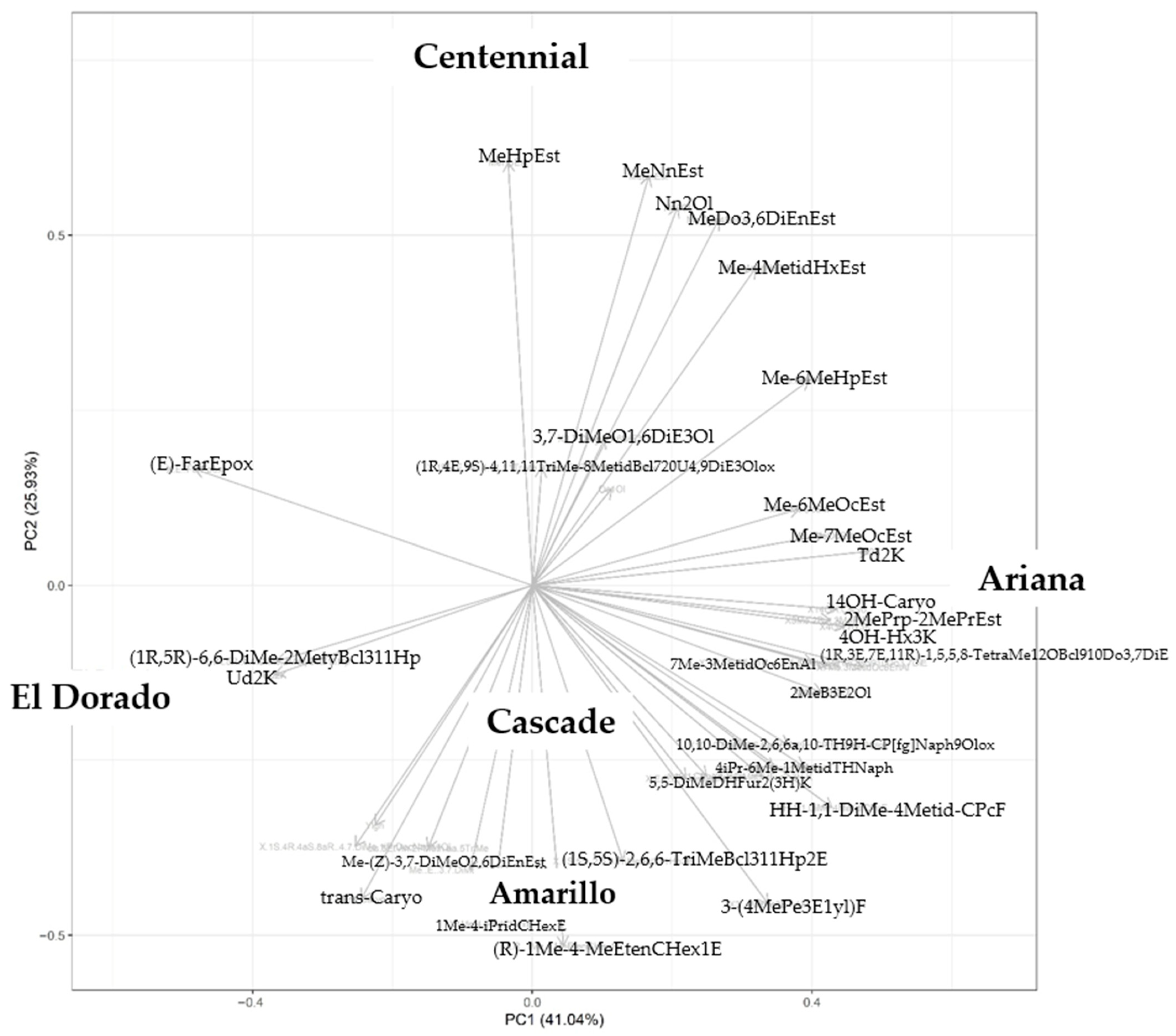

3.8. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of Hop Varieties

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Przybyś, M.; Skomra, U. Hops as a source of biologically active compounds. Pol. J. Agron. 2020, 43, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, G.; Bouchentouf, S.; Kowalski, R.; Wyrostek, J.; Pankiewicz, U.; Mazurek, A.; Sujka, M.; Włodarczyk-Stasiak, M. The hop cones (Humulus lupulus L.): Chemical composition, antioxidant properties and molecular docking simulations. J. Herb. Med. 2022, 33, 100566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herkenhoff, M.E.; Brödel, O.; Frohme, M. Hops across continents: Exploring how terroir transforms the aromatic profiles of five hop (Humulus lupulus) varieties grown in their countries of origin and in Brazil. Plants 2024, 13, 2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takoi, K.; Tokita, K.; Usami, Y.; Matsumoto, I.; Nakayama, Y.-Y.; Takoi, K.; Tokita, K.; Sanekata, A.; Usami, Y.; Itoga, Y.; et al. Varietal Difference of Hop-Derived Flavour Compounds in Late-Hopped/Dry-Hopped Beers. Brew. Sci. 2016, 69, 1–7. Available online: https://www.brewingscience.de/ (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Kishimoto, T.; Wanikawa, A.; Kono, K.; Shibata, K. Comparison of the odor-active compounds in unhopped beer and beers hopped with different hop varieties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 8855–8861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, G.S.; Gallon, M.E.; Gobbo-Neto, L. Mapping Metabolomic Relationships of Hop Cultivars in an Ancestral Lineage Context. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 47281–47291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padgitt-Cobb, L.K.; Pitra, N.J.; Matthews, P.D.; Henning, J.A.; Hendrix, D.A. An improved assembly of the “Cascade” hop (Humulus lupulus) genome uncovers signatures of molecular evolution and refines time of divergence estimates for the Cannabaceae family. Hortic. Res. 2022, 10, uhac281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaguer, C.; Schönberger, C.; Gastl, M.; Arendt, E.K.; Becker, T. Humulus lupulus—A story that begs to be told: A review. J. Inst. Brew. 2014, 120, 289–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyśkiewicz, K.; Gieysztor, R.; Konkol, M.; Szałas, J.; Rój, E. Essential oil from Humulus lupulus scCO2 extract by hydrodistillation and microwave-assisted hydrodistillation. Molecules 2018, 23, 2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, C.L.; Stevens, J.F.; Helmrich, A.; Henderson, M.C.; Rodriguez, R.J.; Yang, Y.H.; Deinzer, M.L.; Barnes, D.W. Antiproliferative and cytotoxic effects of prenylated flavonoids from hops (Humulus lupulus) in human cancer cell lines. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1999, 37, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, L.; Sánchez, C.; Bravo, R.; Rodríguez, A.B.; Barriga, C.; Romero, E. The sedative effect of non-alcoholic beer in healthy female nurses. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J.F.; Page, J.E. Xanthohumol and related prenylflavonoids from hops and beer: To your good health! Phytochemistry 2004, 65, 1317–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lela, L.; Carlucci, V.; Kioussi, C.; Choi, J.; Stevens, J.F.; Milella, L.; Russo, D. Humulus lupulus L.: Evaluation of phytochemical profile and activation of bitter taste receptors to regulate appetite and satiety in intestinal secretin tumor cell line (STC-1 cells). Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2024, 68, e2400559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartsel, J.A.; Eades, J.; Hickory, B.; Makriyannis, A. Cannabis sativa and hemp. In Nutraceuticals, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rufino, A.T.; Ribeiro, M.; Sousa, C.; Judas, F.; Salgueiro, L.; Cavaleiro, C.; Mendes, A.F. Evaluation of the anti-inflammatory, anti-catabolic and pro-anabolic effects of E.-caryophyllene, myrcene and limonene in a cell model of osteoarthritis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 750, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettberg, N.; Biendl, M.; Garbe, L.A. Hop aroma and hoppy beer flavor: Chemical backgrounds and analytical tools—A review. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 2018, 76, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, R.M.; Barciela, J.; Herrero, C.; García-Martín, S. Headspace solid-phase microextraction gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis of volatiles in orujo spirits from a defined geographical origin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 2788–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babič, K.; Strojnik, L.; Ćirić, A.; Ogrinc, N. Optimization and validation of an HS-SPME/GC-MS method for determining volatile organic compounds in dry-cured ham. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1342417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, X.; Yin, Y. Aroma characterization of regional Cascade and Chinook hops (Humulus lupulus L.). Food Chem. 2021, 364, 130410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozzon, M.; Foligni, R.; Mannozzi, C. Brewing quality of hop varieties cultivated in central Italy based on multivolatile fingerprinting and bitter acid content. Foods 2020, 9, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thévenot, E.A.; Roux, A.; Xu, Y.; Ezan, E.; Junot, C. Analysis of the Human Adult Urinary Metabolome Variations with Age, Body Mass Index, and Gender by Implementing a Comprehensive Workflow for Univariate and OPLS Statistical Analyses. J. Proteome Res. 2015, 14, 3322–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jombart, T. adegenet: A R package for the multivariate analysis of genetic markers. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 1403–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, J.I.; Ryu, J.; Seo, K.S.; Kang, K.Y.; Park, S.H.; Ha, T.H.; Ahn, J.W.; Kang, S.Y. Comparative study on phenolic compounds and antioxidant activities of hop (Humulus lupulus L.) strobile extracts. Plants 2022, 11, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resende, G.A.P.; Amaral, M.S.S.; Botelho, B.G.; Marriott, P.J. Comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography–mass spectrometry as a tool for the untargeted study of hop and their metabolites. Metabolites 2024, 14, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibaka, M.L.; Gros, J.; Nizet, S.; Collin, S. Quantitation of selected terpenoids and mercaptans in the dual-purpose hop varieties Amarillo, Citra, Hallertau Blanc, Mosaic, and Sorachi Ace. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 3022–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kankolongo Cibaka, M.L.; Decourrière, L.; Lorenzo-Alonso, C.J.; Bodart, E.; Robiette, R.; Collin, S. 3-Sulfanyl-4-methylpentan-1-ol in Dry-Hopped Beers: First Evidence of Glutathione S-Conjugates in Hop (Humulus lupulus L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 8572–8582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padgitt-Cobb, L.K.; Kingan, S.B.; Wells, J.; Elser, J.; Kronmiller, B.; Moore, D.; Concepcion, G.; Peluso, P.; Rank, D.; Jaiswal, P.; et al. A draft phased assembly of the diploid Cascade hop (Humulus lupulus) genome. Plant Genome 2021, 14, e20072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gent, D.H.; Claassen, B.J.; Wiseman, M.S.; Wolfenbarger, S.N. Temperature influences on powdery mildew susceptibility and development in the hop cultivar Cascade. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 1681–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visin, Y.L.; de Souza, B.C.; Da Costa, F.B. Metabolic profile comparison of hop (Humulus lupulus) cultivars grown in Brazil. Chem. Biodivers. 2025, 1, e01728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leto, L.; Guarrasi, V.; Agosti, A.; Nironi, M.; Chiancone, B.; Juan Vicedo, J. Effects of cytokinins on morphogenesis, total (poly)phenolic content and antioxidant capacity of in vitro-cultured hop plantlets, cvs. Cascade and Columbus. Plants 2025, 14, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditrych, M.; Jędrasik, J.; Królak, K.; Guzińska, N.; Pielech-Przybylska, K.; Ścieszka, S.; Andersen, M.L.; Kordialik-Bogacka, E. Kombucha fortified with Cascade hops (Humulus lupulus L.): Enhanced antioxidative and sensory properties. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 109, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, F.; Yan, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, G. Geraniol and geranyl acetate induce potent anticancer effects in colon cancer Colo-205 cells by inducing apoptosis, DNA damage and cell cycle arrest. J. BUON 2018, 23, 346–352. [Google Scholar]

- Monacci, E.; Baris, F.; Bianchi, A.; Vezzulli, F.; Pettinelli, S.; Lambri, M.; Mencarelli, F.; Chinnici, F.; Sanmartin, C. Influence of the drying process of Cascade hop and the dry-hopping technique on the chemical, aromatic and sensory quality of the beer. Food Chem. 2024, 460, 140594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugapriya, S.; Subramanian, P.; Kanimozhi, S. Geraniol inhibits endometrial carcinoma via downregulating oncogenes and upregulating tumour suppressor genes. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2017, 32, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, S.; Li, X.; Zhuo, X.; Zhang, W.; Nie, Q.; Wang, S.; Yan, L.; Sun, Y. Amentoflavone inhibits osteoclastogenesis and wear debris-induced osteolysis via suppressing NF-κB and MAPKs signaling pathways. Planta Med. 2018, 84, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Y.; Fu, P.; Jun, X.; Cheng, P. Pharmacological properties of geraniol—A review. Planta Med. 2019, 85, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonova-Nedeltcheva, D.; Dobreva, A.; Gechovska, K.; Antonov, L. Volatile compounds profiling of fresh R. alba L. blossom by headspace-solid phase microextraction and gas chromatography. Molecules 2025, 30, 3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojković, M.; Marjanović, D.S.; Medić, D.; Charvet, C.L.; Trailović, S.M. Neuromuscular system of nematodes is a target of synergistic pharmacological effects of carvacrol and geraniol. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezod, U.J.; Salleh, W.M.N.H.W.; Salihu, A.S.; Ab Ghani, N. Chemical composition, anticholinesterase activity, and molecular docking studies of Piper crassipes Korth. ex Miq. essential oil. Nat. Prod. Res. 2025, 39, 4513–4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartuche, L.; Guayllas-Avila, M.; Castillo, L.N.; Morocho, V. Roupala montana Aubl. essential oil: Chemical composition and emerging biological activities. Molecules 2025, 30, 3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Wang, S.; Jiang, L.; Sun, X.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Yao, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, N.; Deng, H.; et al. 2-Undecanone protects against fine particles-induced heart inflammation via modulating Nrf2/HO-1 and NF-κB pathways. Environ. Toxicol. 2022, 37, 1642–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargali, P.; Kumar, R.; Joshi, S.; Karakoti, H.; Gautam, S.; Rawat, S.; Rawat, D.S. Artemisia annua L. essential oil-loaded chitosan nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization, in-vitro release kinetics, and acetylcholinesterase inhibition as a mode of action against plant-parasitic nematodes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 313, 144221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onjura, C.O.; Peter, E.; Asudi, G.O.; Gicheru, M.M.; Mohamed, S.A.; Bruce, T.J.A.; Tamiru, A. Differential responses of the egg-larval parasitoid Chelonus bifoveolatus to fall armyworm-induced and constitutive volatiles of diverse maize genotypes. J. Chem. Ecol. 2025, 51, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.; Kim, M.J.; Dhandapani, S.; Tjhang, J.G.; Yin, J.L.; Wong, L.; Sarojam, R.; Chua, N.H.; Jang, I.C. The floral transcriptome of ylang ylang (Cananga odorata var. fruticosa) uncovers biosynthetic pathways for volatile organic compounds and a multifunctional and novel sesquiterpene synthase. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 3959–3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhandapani, S.; Tjhang, J.G.; Jang, I.C. Production of multiple terpenes of different chain lengths by subcellular targeting of multi-substrate terpene synthase in plants. Metab. Eng. 2020, 61, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Hop Variety | Origin | Typical Use | Alpha Acid (%) | Aroma Characteristics | Equivalent Substitutes | Citric | Fruity | Floral |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amarillo | United States | Aroma | 10.34 | Citrus, Orange, Passion Fruit, Sweet; | Cascade, Centennial, Ahtanum, Chinook, Summer; | |||

| Ariana | Germany | Aroma/Bitter | 8.6 | Fruity, Citric, Red Fruit | Mandarina Bavaria, Hallertau Blanc; | |||

| Cascade | United States | Aroma | 7.45 | Citrus, Fruity, Floral and lesser, Earthy and Spicy; | Ahtanum, Amarillo, Centennial, Columbus; | |||

| Centennial | Brazil | Aroma/Bitter | 10 | Citrus, Floral, Fruity, Herb, Spicy; | Cascade, Chinook, Columbus; | |||

| El Dorado | United States | Aroma/Bitter | 14 | Fruity | Galena, Nugget, Simcoe; |

| Compound | CAS | Odor | Flavor | Amarillo | Ariana | Cascade | Centennial | El Dorado | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Type | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Propan-2-one | 67-64-1 | Solvent | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.017 | 0.006 | |||||

| 2-Methylpropenal | 78-85-3 | Floral | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.006 | |||||||

| 2-Methylbut-3-en-2-ol | 115-18-4 | Herbal | 0.123 | 0.029 | 0.413 | 0.195 | 0.373 | 0.098 | 0.077 | 0.023 | 0.033 | 0.012 | |

| Methyl 3-methylbutanoate | 556-24-1 | Fruity | Fruity | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.060 | 0.104 | ||||||

| Dimethyldisulfide | 624-92-0 | Sulfurous | 0.020 | 0.001 | |||||||||

| Alpha-Pinene | 80-56-8 | Herbal | Woody | 0.137 | 0.029 | 0.220 | 0.001 | 0.093 | 0.029 | 0.017 | 0.006 | 0.183 | 0.006 |

| 2-Methylbutan-1-ol | 137-32-6 | Etheral | Etheral | 0.103 | 0.006 | 0.103 | 0.012 | 0.017 | 0.006 | 0.130 | 0.001 | ||

| Camphene | 79-92-5 | Woody | Camphoreus | 0.087 | 0.012 | 0.083 | 0.006 | ||||||

| 2-Methylpropyl propanoate | 540-42-1 | Fruity | Fruity | 0.020 | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.006 | ||||||

| Hexanal | 66-25-1 | Green | Green | 0.010 | 0.001 | ||||||||

| Beta-Pinene | 127-91-3 | Herbal | Pine | 0.293 | 0.040 | 0.607 | 0.040 | 0.413 | 0.081 | 0.240 | 0.069 | 13.547 | |

| 2-Methylbutyl acetate | 624-41-9 | Fruity | Fruity | 0.050 | 0.044 | ||||||||

| 2-Methylpropyl 2-methylpropanoate | 97-85-8 | Fruity | Fruity | 0.030 | 0.001 | 0.997 | 0.021 | 0.050 | 0.001 | 0.033 | 0.012 | ||

| 3-Methylbut-2-en-1-ol | 556-82-1 | Fruity | Fruity | 0.033 | 0.012 | 0.057 | 0.032 | 0.067 | 0.012 | ||||

| (E)-Myrca-1.3-diene | 123-35-3 | Spicy | Woody | 22.613 | 0.531 | 13.933 | 21.213 | 0.150 | 2.463 | 0.722 | |||

| (1R.6R)-p-Mentha-1.5-diene | 99-83-2 | Terpenic | Terpenic | 0.010 | 0.017 | 0.020 | 0.017 | 0.027 | 0.012 | 0.020 | 0.001 | ||

| (E)-Pent-2-enal | 1576-87-0 | Green | Green | 0.010 | 0.001 | ||||||||

| Geranyl isovalerate | 109-20-6 | Fruity | Green | 2.830 | 0.001 | ||||||||

| 3-Methylbut-2-enal | 107-86-8 | Fruity | Fruity | 0.087 | 0.035 | 0.053 | 0.006 | ||||||

| Methyl hexanoate | 106-70-7 | Fruity | Fruity | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.023 | 0.012 | ||||

| Butyl 2-methylpropanoate | 97-87-0 | Fruity | Fruity | 0.020 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.006 | ||||||

| Alpha-Terpinene | 99-86-5 | Woody | Terpenic | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.001 | ||||

| (+)-Limonene | 5989-27-5 | Citrus | Citrus | 1.120 | 0.087 | 1.093 | 0.032 | 0.663 | 0.029 | 0.263 | 0.081 | 1.090 | 0.026 |

| S-Methyl 3-methylbutanethioate | 23747-45-7 | Cheesy | Fermented | 0.040 | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.012 | 0.023 | 0.012 | 0.017 | 0.006 | ||

| Ethyl 4-methylpentanoate | 25415-67-2 | Fruity | 0.007 | 0.006 | |||||||||

| (6R)-p-Mentha-1.5-diene | 555-10-2 | Minty | 0.030 | 0.017 | 0.063 | 0.012 | 0.113 | 0.029 | 0.173 | 0.023 | |||

| (E)-3.7-Dimethylocta-1.3.6-triene | 3779-61-1 | Herbal | 0.017 | 0.006 | |||||||||

| 3-Methylbutyl propanoate | 105-68-0 | Fruity | Fruity | 0.050 | 0.001 | ||||||||

| 2-Methylbutyl propanoate | 2438-20-2 | Fruity | 0.263 | 0.006 | |||||||||

| (+-)-alpha-Pinene | 80-56-8 | Herbal | Woody | 0.020 | 0.001 | 0.030 | 0.001 | 0.133 | 0.006 | ||||

| Hexan-1-ol | 111-27-3 | Herbal | Green | 0.020 | 0.001 | 0.020 | 0.001 | 0.017 | 0.006 | ||||

| 2-Methylpropyl 2-methylbutanoate | 2445-67-2 | Fruity | Fruity | 0.487 | 0.021 | ||||||||

| (Z)-3.7-Dimethylocta-1.3.6-triene | 3338-55-4 | Floral | Green | 0.740 | 0.156 | ||||||||

| 2-Methylpropyl 3-methylbutanoate | 589-59-3 | Fruity | Green | 0.030 | 0.001 | 0.127 | 0.006 | 0.040 | 0.001 | ||||

| 3.7-Dimethylocta-1.3.6-triene | 502-99-8 | Fruity | 2.047 | 0.151 | |||||||||

| Hexyl pentanoate | 1117-59-5 | Fruity | 0.040 | 0.001 | |||||||||

| 2-Methylbutyl 2-methylpropanoate | 2445-69-4 | Fruity | 0.673 | 0.023 | 0.883 | 0.058 | 0.260 | 0.087 | 1.730 | 0.026 | |||

| Ethyl hexanoate | 123-66-0 | Fruity | Fruity | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.033 | 0.012 | ||||||

| Methyl 4-methylpentanoate | 2412-80-8 | Fruity | Fruity | 0.087 | 0.006 | 0.033 | 0.006 | 0.063 | 0.012 | 0.037 | 0.012 | ||

| Methyl (Z)-octadec-9-enoate | 112-62-9 | Fatty | 0.010 | 0.001 | |||||||||

| Dodecane (nome já IUPAC) | 112-40-3 | Alkane | 0.047 | 0.012 | 0.080 | 0.001 | 0.057 | 0.012 | 0.007 | 0.006 | |||

| 1-Methyl-4-(propan-2-ylidene)cyclohexene | 586-62-9 | Herbal | Woody | 0.037 | 0.006 | 0.033 | 0.006 | 0.020 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.040 | 0.001 |

| Butyl 2-methylbutanoate | 15706-73-7 | Fruity | Fruity | 0.047 | 0.081 | ||||||||

| Hexyl acetate | 142-92-7 | Fruity | Fruity | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.077 | 0.006 | 0.013 | 0.006 | ||||

| Pentyl 2-methylpropanoate | 2445-72-9 | Fruity | 0.073 | 0.006 | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.001 | |||||

| Methyl heptanoate | 106-73-0 | Fruity | Fruity | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.020 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.180 | 0.035 | 0.010 | 0.001 |

| (E)-Myrcene | 123-35-3 | Spice | Woody | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.023 | 0.012 | ||||

| (Z)-Hex-3-en-1-yl acetate | 3681-71-8 | Green | Green | 0.007 | 0.006 | ||||||||

| Cyclopropanecarboxaldehyde | 97231-35-1 | Citrus | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.001 | |||||||

| 3-Methyl-2-butenyl 2-methylpropanoate | 76649-23-5 | Fruity | 0.020 | 0.001 | 0.167 | 0.006 | 0.020 | 0.017 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.010 | 0.001 | |

| Oct-1-en-3-ol | 3391-86-4 | Earthy | Mushroom | 0.040 | 0.001 | 0.037 | 0.012 | 0.020 | 0.001 | ||||

| 6-Methylhept-5-en-2-one | 110-93-0 | Citrus | Green | 0.253 | 0.012 | 0.260 | 0.052 | 0.107 | 0.023 | ||||

| 3-Methylbutyl 2-methylbutanoate | 27625-35-0 | Fruity | Fruity | 0.083 | 0.012 | 0.030 | 0.001 | ||||||

| 2-Methylbutyl 2-methylbutanoate | 2445-78-5 | Fruity | Fruity | 0.763 | 0.055 | 0.270 | 0.052 | 0.327 | 0.006 | ||||

| 3-Methylbutyl 3-methylbutanoate | 659-70-1 | Fruity | Green | 0.210 | 0.035 | ||||||||

| 3-Methylbutanoic acid | 503-74-2 | Cheesy | Cheesy | 0.567 | 0.023 | 0.367 | 0.076 | 0.100 | 0.035 | 0.093 | 0.006 | ||

| 2-Methylbutyl 3-methylbutanoate | 2445-77-4 | Fruity | Fruity | 0.353 | 0.012 | 0.613 | 0.038 | 0.060 | 0.017 | 0.290 | 0.010 | ||

| Ethyl heptanoate | 106-30-9 | Fruity | Fruity | 0.053 | 0.012 | ||||||||

| (Z)-Hex-3-en-1-yl butanoate | 16491-36-4 | Green | Green | 0.120 | 0.010 | ||||||||

| 3-[4-Methylpent-3-en-1-yl]furan | 539-52-6 | Woody | 0.410 | 0.069 | 0.470 | 0.050 | 0.290 | 0.035 | 0.027 | 0.012 | 0.163 | 0.023 | |

| Hexyl propanoate | 2445-76-3 | Fruity | 0.107 | 0.012 | 0.007 | 0.006 | |||||||

| (Z)-Hex-3-en-1-yl propanoate | 33467-74-2 | Green | Green | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.020 | 0.001 | ||||||

| S-Methyl hexanethioate | 2432-77-1 | Fruity | 0.027 | 0.006 | |||||||||

| 2-Furanmethanol | 34995-77-2 | Floral | 0.087 | 0.006 | 0.640 | 0.053 | 0.120 | 0.017 | |||||

| Methyl octanoate | 111-11-5 | Waxy | Green | 0.110 | 0.010 | 0.033 | 0.006 | 0.157 | 0.023 | ||||

| 2-Methylpropyl hexanoate | 105-79-3 | Fruity | Fruity | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.001 | ||||||

| 1.3.8-p-Menthatriene | 18368-95-1 | Terpenic | Terpenic | 0.007 | 0.006 | ||||||||

| Benzaldehyde | 100-52-7 | Fruity | Fruity | 0.030 | 0.001 | 0.030 | 0.001 | 0.030 | 0.001 | ||||

| Methyl octanoate | 111-11-5 | Waxy | Green | 0.030 | 0.001 | ||||||||

| 2-Methylpropyl hexanoate | 105-79-3 | Fruity | Fruity | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||||||||

| Benzaldehyde | 100-52-7 | Fruity | Fruity | 0.030 | 0.001 | ||||||||

| 1.3.8-p-Menthatriene | 18368-95-1 | Terpenic | Terpenic | 0.013 | 0.006 | ||||||||

| Ethyl octanoate | 106-32-1 | Waxy | Waxy | 0.003 | 0.006 | ||||||||

| Nonan-2-one | 821-55-6 | Fruity | Cheesy | 0.210 | 0.017 | 0.187 | 0.006 | 0.330 | 0.035 | 0.113 | 0.006 | ||

| Nonan-2-ol | 628-99-9 | Waxy | Waxy | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.020 | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.006 | 0.037 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Octan-1-ol | 111-87-5 | Waxy | Waxy | 0.057 | 0.006 | 0.070 | 0.010 | 0.023 | 0.006 | 0.057 | 0.006 | 0.057 | 0.006 |

| 3.7-Dimethylocta-1.6-dien-3-ol | 78-70-6 | Floral | Citrus | 2.700 | 0.121 | 1.617 | 0.071 | 1.840 | 0.191 | 2.750 | 0.139 | 0.960 | 0.035 |

| Ethyl octanoate | 106-32-1 | Waxy | Waxy | 0.007 | 0.006 | ||||||||

| Heptyl propanoate | 2216-81-1 | Floral | Fruity | 0.057 | 0.006 | 0.020 | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.006 | ||||

| (-)-Caryophyllene | 87-44-5 | Spicy | Spicy | 0.023 | 0.006 | 0.013 | 0.006 | ||||||

| Hexyl 2-methylbutanoate | 10032-15-2 | Green | Green | 0.047 | 0.006 | ||||||||

| Decan-2-one | 693-54-9 | Floral | Fermented | 0.060 | 0.001 | 0.257 | 0.015 | 0.067 | 0.012 | 0.020 | 0.001 | 0.043 | 0.006 |

| Octyl acetate | 112-14-1 | Floral | Waxy | 0.040 | 0.001 | 0.150 | 0.010 | 0.033 | 0.006 | 0.010 | 0.001 | ||

| Heptyl 2-methylpropanoate | 2349-13-5 | Fruity | Berry | 0.023 | 0.006 | 0.153 | 0.012 | 0.070 | 0.001 | ||||

| Alpha-Cubebene | 17699-14-8 | Herbal | 0.067 | 0.029 | 0.193 | 0.012 | |||||||

| Fenchol | 1632-73-1 | Camphoreous | Camphoreous | 0.047 | 0.006 | 0.027 | 0.006 | ||||||

| (-)-Isopulegol | 89-79-2 | Minty | Minty | 0.007 | 0.006 | ||||||||

| Methyl nonanoate | 1731-84-6 | Fruity | Winey | 0.027 | 0.012 | 0.083 | 0.006 | 0.027 | 0.006 | 0.150 | 0.017 | 0.013 | 0.006 |

| Hexanoic acid | 142-62-1 | Fatty | Cheesy | 0.053 | 0.012 | 0.053 | 0.012 | 0.040 | 0.001 | 0.037 | 0.006 | 0.033 | 0.006 |

| 2-Methylbutyl hexanoate | 2601-13-0 | Ethereal | 0.020 | 0.001 | 0.030 | 0.001 | 0.047 | 0.006 | 0.023 | 0.006 | |||

| Methyl non-3-enoate | 13481-87-3 | Fruity | Fruity | 0.020 | 0.001 | 0.043 | 0.006 | 0.233 | 0.012 | ||||

| Copa-3.8-diene | 3856-25-5 | Woody | 1.417 | 0.075 | 1.133 | 0.091 | 1.027 | 0.098 | 0.570 | 0.069 | |||

| Decan-2-one | 693-54-9 | Floral | Fermented | 0.393 | 0.015 | 0.207 | 0.012 | 0.533 | 0.012 | ||||

| 3.7-Dimethylocta-2.6-dien-1-ol | 106-24-1 | Floral | Floral | 0.017 | 0.012 | 0.020 | 0.001 | ||||||

| (E)-3.7-Dimethylocta-2.6-dien-1-yl acetate | 105-87-3 | Floral | Green | 0.010 | 0.010 | ||||||||

| Methyl 3.7-dimethyloct-6-enoate | 2270-60-2 | Floral | Floral | 0.027 | 0.012 | ||||||||

| 7-Methyl-3-methyleneoct-6-enal | 55050-40-3 | Aldehylic | 0.247 | 0.012 | 0.283 | 0.006 | 0.213 | 0.023 | 0.197 | 0.006 | 0.143 | 0.023 | |

| 5-Methylhexanoic acid | 628-46-6 | Fatty | 0.053 | 0.006 | 0.103 | 0.021 | 0.027 | 0.006 | |||||

| Borneol | 507-70-0 | Balsamic | 0.037 | 0.012 | 0.033 | 0.006 | |||||||

| (-)-Borneol | 464-45-9 | Balsamic | 0.033 | 0.006 | |||||||||

| 2.6-Dimethylocta-1.5.7-trien-3-ol | 29414-56-0 | Camphoreous | 0.240 | 0.087 | 0.200 | 0.087 | 0.477 | 0.248 | 0.437 | 0.156 | |||

| Octyl propanoate | 142-60-9 | Fruity | Estery | 0.080 | 0.017 | 0.023 | 0.006 | ||||||

| Octyl 2-methylpropanoate | 109-15-9 | Waxy | Creamy | 0.143 | 0.029 | 0.050 | 0.017 | ||||||

| Methyl (Z)-3.7-dimethylocta-2.6-dienoate | 1862-61-9 | Floral | 0.060 | 0.001 | |||||||||

| Trans-alpha-Bergamotene | 13474-59-4 | Woody | 0.620 | 0.208 | 1.013 | 0.300 | 0.960 | 0.831 | |||||

| Gamma-Muurolene | 30021-74-0 | Woody | 24.740 | 20.587 | 23.060 | 0.083 | 0.012 | ||||||

| Undecan-2-one | 112-12-9 | Fruity | Waxy | 8.000 | 0.554 | 8.147 | 0.327 | 8.993 | 0.248 | 8.207 | 0.115 | 10.470 | 0.718 |

| (-)-Caryophyllene | 87-44-5 | Spicy | Spicy | 5.713 | 0.127 | 2.583 | 0.192 | 5.520 | 0.121 | 3.063 | 0.133 | 4.737 | |

| Citronellal | 106-23-0 | Floral | Floral | 0.140 | 0.001 | ||||||||

| (6Z)-beta-Farnesene | 28973-97-9 | Green | 14.717 | ||||||||||

| Gamma-Cadinene | 39029-41-9 | Woody | 13.080 | ||||||||||

| Beta-Farnesene | 18794-84-8 | Woody | 5.957 | 0.092 | 5.713 | 0.081 | 0.130 | 0.017 | |||||

| Geraniol | 106-24-1 | Floral | Floral | 2.393 | 0.202 | 2.223 | 0.158 | ||||||

| Methyl undecanoate | 1731-86-8 | Waxy | 0.123 | 0.015 | |||||||||

| Dodecan-2-one | 6175-49-1 | Citrus | 3.317 | 0.287 | |||||||||

| Gamma-Cadinene | 39029-41-9 | Woody | 12.263 | 0.949 | |||||||||

| Humulene | 6753-98-6 | Woody | 5.240 | 0.433 | 4.540 | 0.195 | 5.700 | 0.121 | 4.180 | 0.104 | 3.540 | 0.380 | |

| Beta-Bisabolene | 495-61-4 | Balsamic | 0.210 | 0.017 | |||||||||

| (-)-Alpha-muurolene | 10208-80-7 | Woody | 0.487 | 0.023 | 0.433 | 0.023 | 3.013 | 0.375 | |||||

| Geranyl Acetate | 105-87-3 | Floral | Green | 0.663 | 0.029 | 4.767 | 0.539 | 1.907 | 0.219 | ||||

| Beta-Selinene | 17066-67-0 | Herbal | 2.143 | 0.348 | 4.793 | 0.670 | |||||||

| Farnesene | 502-61-4 | Woody | Green | 0.120 | 0.001 | 0.087 | 0.012 | 0.053 | 0.046 | 0.197 | 0.015 | ||

| Delta-Cadinene | 483-76-1 | Herbal | 2.470 | 0.260 | 2.293 | 0.203 | 2.243 | 0.058 | 0.737 | 0.144 | |||

| (-)-alpha-Gurjunene | 489-40-7 | Woody | 0.503 | 0.196 | |||||||||

| Beta-Cadinene | 523-47-7 | Woody | 0.113 | 0.012 | |||||||||

| Gamma-Cadinene | 39029-41-9 | Woody | 1.153 | 0.254 | 1.517 | 0.045 | |||||||

| Beta-Sesquiphellandrene | 20307-83-9 | Herbal | 0.007 | 0.006 | |||||||||

| Guaiyl acetate | 134-28-1 | Balsamic | 0.150 | 0.017 | |||||||||

| Neryl isobutyrate | 2345-24-6 | Fruity | Fruity | 0.010 | 0.001 | ||||||||

| Neryl propionate | 105-91-9 | Fruity | Green | 0.030 | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.006 | 0.027 | 0.012 | 0.020 | 0.001 | ||

| Calamenene | 483-77-2 | Herbal | 0.270 | 0.087 | 0.103 | 0.029 | |||||||

| Neryl butyrate | 999-40-6 | Green | Green | 0.013 | 0.006 | 0.010 | 0.001 | ||||||

| Perillyl acetate | 15111-96-3 | Fruity | Green | 0.007 | 0.006 | ||||||||

| Perillyl Alcohol | 536-59-4 | Green | Woody | 0.053 | 0.006 | 0.063 | 0.029 | ||||||

| Geranyl propionate | 105-90-8 | Floral | Waxy | 0.233 | 0.006 | 0.083 | 0.006 | ||||||

| Geranyl butyrate | 106-29-6 | Fruity | Fruity | 1.360 | 0.156 | 0.577 | 0.012 | 0.847 | 0.051 | ||||

| Germacrene B | 15423-57-1 | Woody | 0.290 | 0.156 | |||||||||

| cis-Linalool oxide | 5989-33-3 | Earthy | 0.013 | 0.006 | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.017 | 0.006 | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.006 | |

| Cyclohexadec-5-en-1-one | 37609-25-9 | Musk | 0.010 | 0.001 | |||||||||

| Alpha-Calacorene | 21391-99-1 | Woody | 0.043 | 0.029 | |||||||||

| Nerolidol | 40716-66-3 | Floral | Green | 0.023 | 0.006 | ||||||||

| Geranyl 2-methylbutyrate | 68705-63-5 | Fruity | 0.017 | 0.006 | |||||||||

| Cyclopentadecanone | 502-72-7 | Musk | 0.003 | 0.006 | |||||||||

| Neryl isovalerate | 3915-83-1 | Floral | 0.017 | 0.006 | |||||||||

| Geranyl valerate | 10402-47-8 | Floral | 0.010 | 0.001 | |||||||||

| Cubenol | 21284-22-0 | Spicy | Spicy | 0.020 | 0.001 | 0.040 | 0.001 | ||||||

| Caryophyllene oxide | 1139-30-6 | Woody | Woody | 0.050 | 0.001 | 0.053 | 0.035 | 0.117 | 0.023 | 0.087 | 0.012 | 0.050 | 0.001 |

| (4E,7E)-1,5,9,9-Tetramethyl-12-oxabicyclo(9.1.0)dodeca-4,7-diene | 19888-33-6 | Herbal | 0.060 | 0.001 | 0.063 | 0.021 | 0.077 | 0.006 | 0.033 | 0.006 | 0.010 | 0.001 | |

| Alpha-Cadinol | 481-34-5 | Herbal | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.001 | |||||

| Beta-Eudesmol | 473-15-4 | Woody | 0.120 | 0.001 | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Herkenhoff, M.E.; Brödel, O.; Dilarri, G.; Bajay, M.M.; Frohme, M.; Costamilan, C.A.d.V.L.R. Characterization of Volatile Compounds in Amarillo, Ariana, Cascade, Centennial, and El Dorado Hops Using HS-SPME/GC-MS. Compounds 2026, 6, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/compounds6010004

Herkenhoff ME, Brödel O, Dilarri G, Bajay MM, Frohme M, Costamilan CAdVLR. Characterization of Volatile Compounds in Amarillo, Ariana, Cascade, Centennial, and El Dorado Hops Using HS-SPME/GC-MS. Compounds. 2026; 6(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/compounds6010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleHerkenhoff, Marcos Edgar, Oliver Brödel, Guilherme Dilarri, Miklos Maximiliano Bajay, Marcus Frohme, and Carlos André da Veiga Lima Rosa Costamilan. 2026. "Characterization of Volatile Compounds in Amarillo, Ariana, Cascade, Centennial, and El Dorado Hops Using HS-SPME/GC-MS" Compounds 6, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/compounds6010004

APA StyleHerkenhoff, M. E., Brödel, O., Dilarri, G., Bajay, M. M., Frohme, M., & Costamilan, C. A. d. V. L. R. (2026). Characterization of Volatile Compounds in Amarillo, Ariana, Cascade, Centennial, and El Dorado Hops Using HS-SPME/GC-MS. Compounds, 6(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/compounds6010004