Relationship of Metallophilic Interactions with Structural and Mechanical Properties of (1−x) (0.73GeSe2-0.27Sb2Se3)-xAg2Se Glasses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

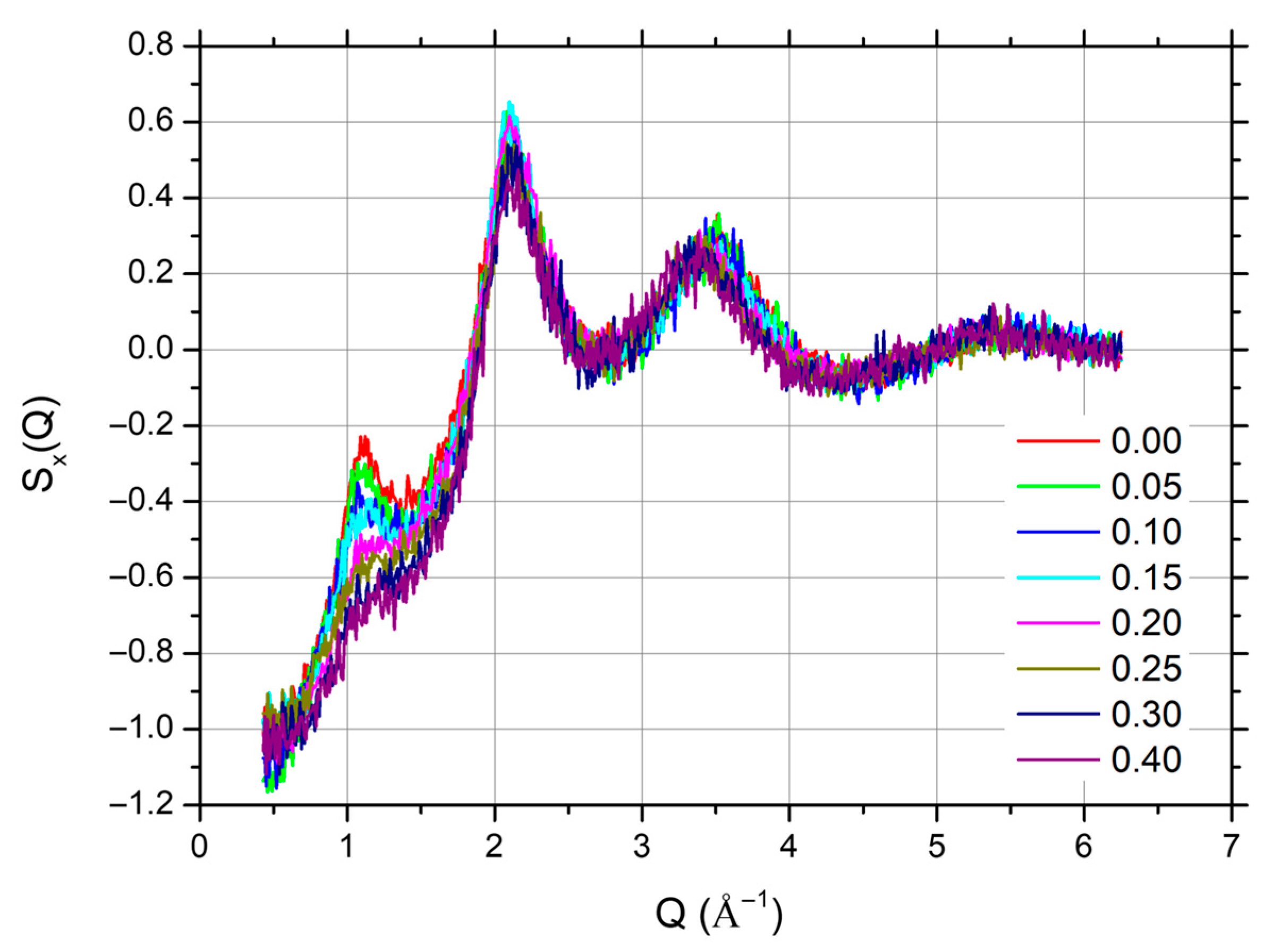

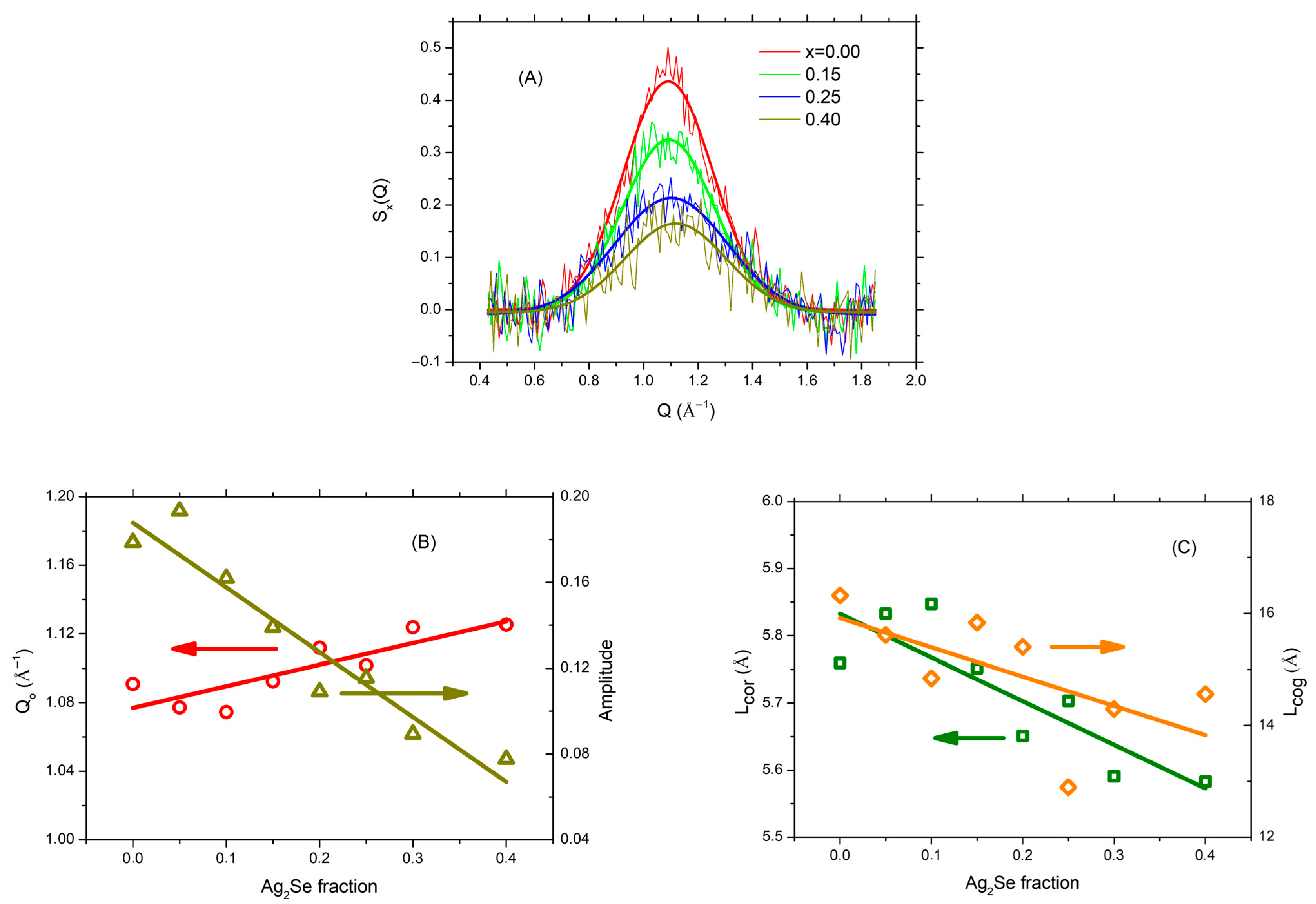

3.1. XRD Data and Analysis

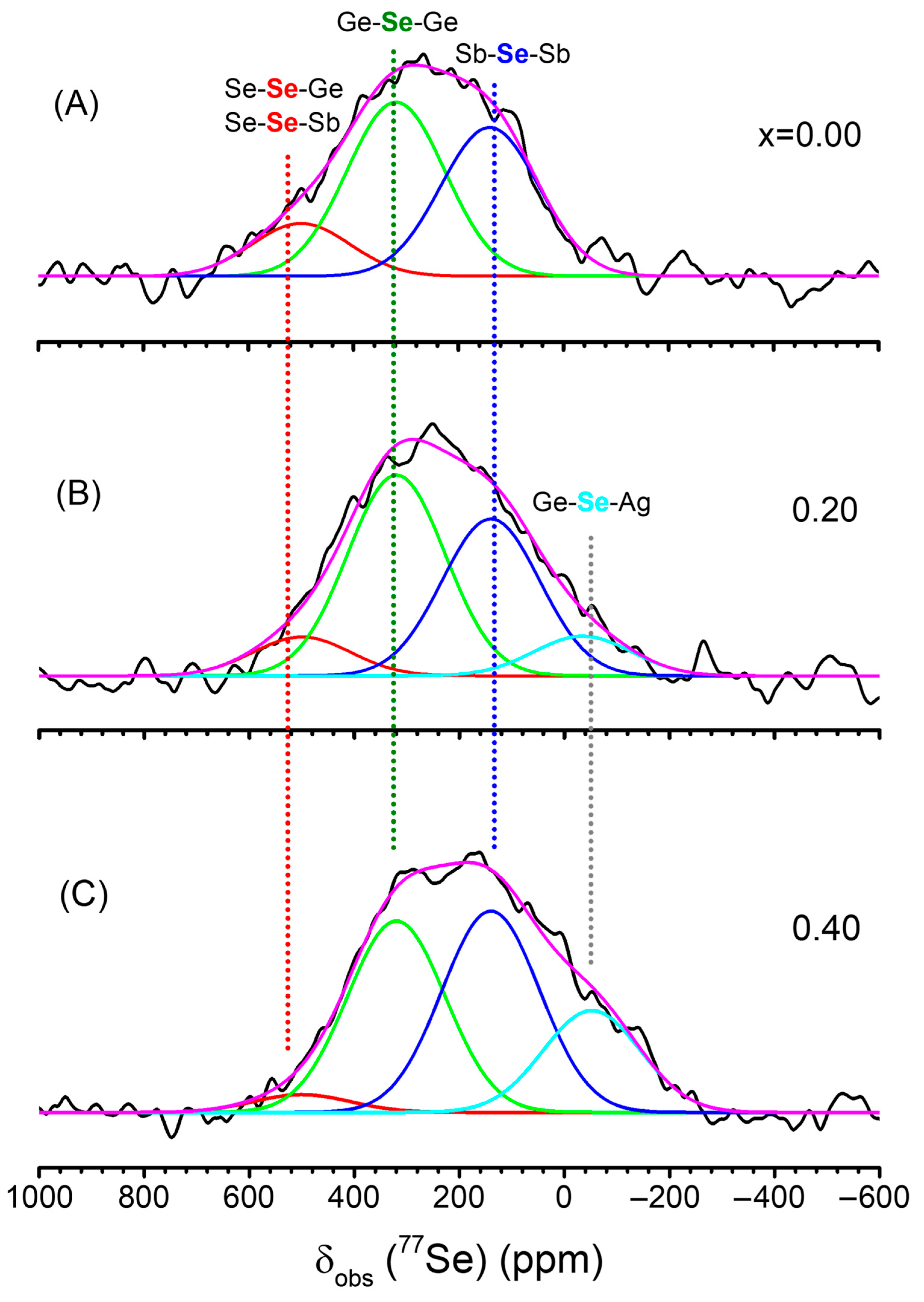

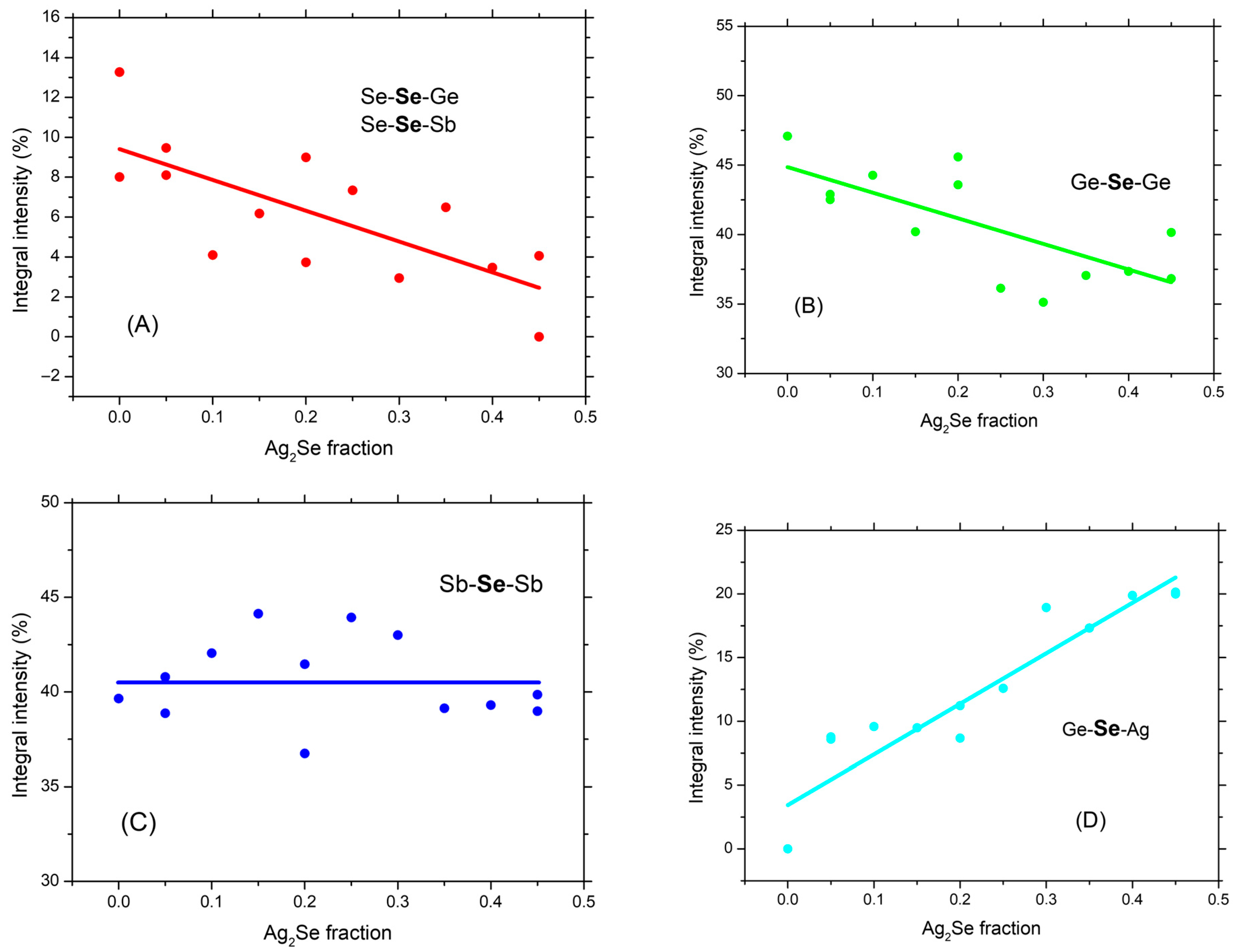

3.2. NMR Data and Analysis

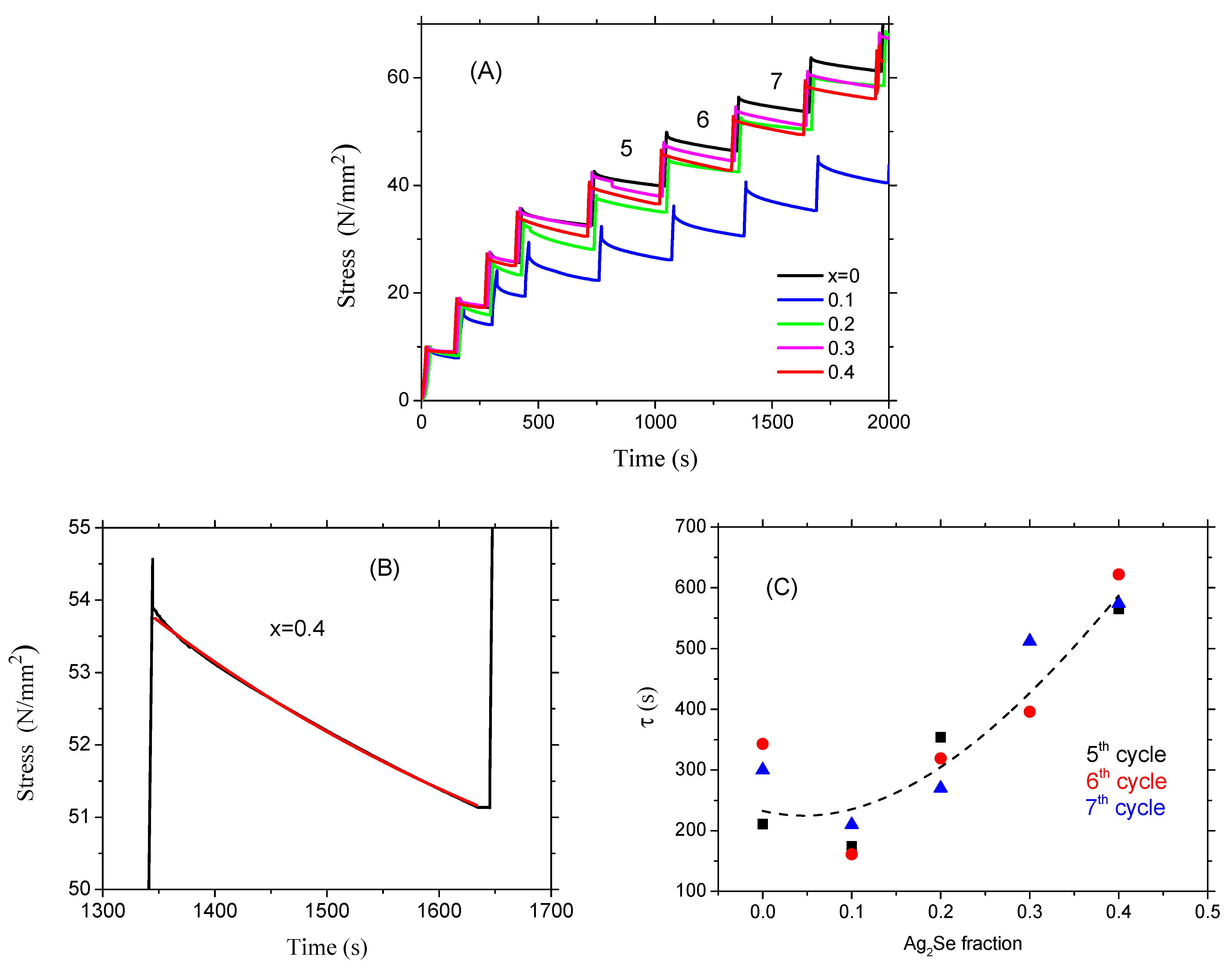

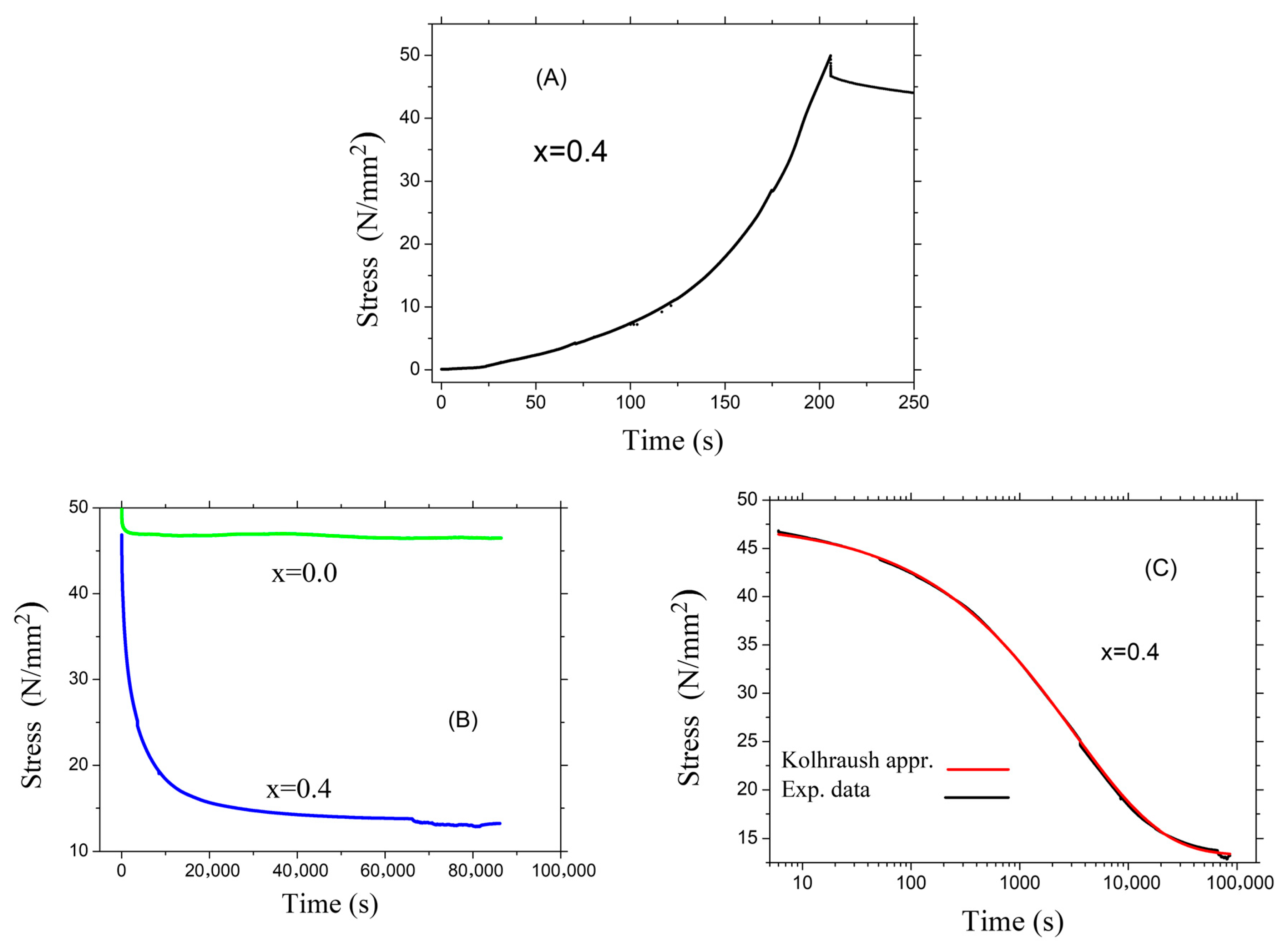

3.3. Mechanical Properties of the Glasses

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, K.; Pan, J.; Yin, W.; Ma, C.; Wang, L. Flexible electronics based on one-dimensional inorganic semiconductor nanowires and two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 108226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wei, T.-R.; Zhao, K.; Qiu, P.; Chen, L.; He, J.; Shi, X. Room-temperature plastic inorganic semiconductors for flexible and deformable electronics. InfoMat 2021, 3, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Cao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Feng, X. Flexible and stretchable inorganic optoelectronics. Opt. Mater. Express 2019, 9, 4023–4049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Ota, H.; Kiriya, D.; Takei, K.; Javey, A. Flexible Electronics toward Wearable Sensing. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Dun, G.; Geng, X.; Chen, J.; Wu, X.; Ren, T.-L. Recent progress in flexible micro-pressure sensors for wearable health monitoring. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 5, 3131–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Son, D.; Choi, M.K.; Kim, D.-H. Deformable devices with integrated functional nanomaterials for wearable electronics. Nano Converg. 2016, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, C.C.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, J. Flexible wearable sensors—An update in view of touch-sensing. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2021, 22, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, A.M.; Tayebi, L.; Abbasi, M.; Vaez, A.; Kamyab, H.; Chelliapan, S.; Vafa, E. The Need for Smart Materials in an Expanding Smart World: MXene-Based Wearable Electronics and Their Advantageous Applications. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 3123–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisula, W. Inorganic Semiconductors in Electronic Applications. Electron. Mater. 2023, 4, 136–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sun, M.; Hung, N.T. Advanced Inorganic Semiconductor Materials. Inorganics 2024, 12, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.J.; Yan, Z.; Han, M. Inorganic semiconducting materials for flexible and stretchable electronics. npj Flex. Electron. 2017, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Chen, H.; Hao, F.; Liu, R.; Wang, T.; Qiu, P.; Burkhardt, U.; Grin, Y.; Chen, L. Room-temperature ductile inorganic semiconductor. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Wang, T.; Qiu, P.; Yang, S.; Ming, C.; Chen, H.; Song, Q.; Zhao, K.; Wei, T.-R.; Ren, D.; et al. Flexible thermoelectrics: From silver chalcogenides to full-inorganic devices. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 2983–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Shi, X.-L.; Wu, H.; Liu, Q.; Chen, Z.-G. Advances in Ag2S-based thermoelectrics for wearable electronics: Progress and perspective. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 473, 145236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadovnikov, S.I.; Kostenko, M.G.; Gusev, A.I.; Lukoyanov, A.V. Low-Temperature Predicted Structures of Ag2S (Silver Sulfide). Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, B.; Li, R.; Zhu, M.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, C. Deformation Mechanisms of Inorganic Thermoelectric Materials with Plasticity. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2024, 5, 2300197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Liang, J.-S.; Shi, X.; Zhang, Z. Full-Inorganic Flexible Ag2S Memristor with Interface Resistance−Switching for Energy-Efficient Computing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 43482–43489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Shi, X.-L.; Li, M.; Nisar, M.; Mansoor, A.; Chen, S.; Chen, Y.; Li, F.; Ma, H.; Liang, G.X.; et al. Flexible power generators by Ag2Se thin films with record-high thermoelectric performance. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Yang, S.; Qiu, P.; Peng, L.; Wei, T.-R.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, X.; Chen, L. Flexible thermoelectrics based on ductile semiconductors. Science 2022, 377, 854–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evarestov, R.A.; Panin, A.I.; Tverjanovich, Y.S. Argentophillic interactions in argentum chalcogenides: First principles calculations and topological analysis of electron density. J. Comput. Chem. 2021, 42, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanon, K.; Sharif, S.S.; Irfan, A.; Sharif, A. Inorganic film materials for flexible electronics: A brief overview, properties, and applications. Eng. Rep. 2024, 6, e13006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-H.; Lu, N.; Ghaffari, R.; Rogers, J.A. Inorganic semiconductor nanomaterials for flexible and stretchable bio-integrated electronics. NPG Asia Mater. 2012, 4, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Cheng, R.; Liao, L.; Duan, X. High performance thin film electronics based on inorganic nanostructures and composites. Nano Today 2013, 8, 514–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.-J.; Lee, K.J.; Jo, K.-W.; Katz, H.E.; Cho, W.-J.; Shin, Y.-B. Top-down Fabrication and Enhanced Active Area Electronic Characteristics of Amorphous Oxide Nanoribbons for Flexible Electronics. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, R.V. Editorial for Special Issue on Flexible Electronics: Fabrication and Ubiquitous Integration. Micromachines 2018, 9, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Navaraj, W.T.; Lorenzelli, L.; Dahiya, R. Ultra-thin chips for high-performance flexible electronics. npj Flex. Electron. 2018, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Han, L.; Hu, H.; Zhang, R. A review on polymers and their composites for flexible electronics. Mater. Adv. 2023, 4, 726–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, H.; Liu, S.; Zheng, Z.; Yan, F. Organic Flexible Electronics. Small Methods 2018, 2, 1800070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, D.; Yang, J.; Gao, H.; Wu, Y. Flexible Electronics Based on Organic Semiconductors: From Patterned Assembly to Integrated Applications. Small 2023, 19, 2206938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, F.; Zimmer, J. Chemically Toughened Flexible Ultrathin Glass. U.S. Patent 2016/0002103 A1, 7 January 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Langgemach, W.; Baumann, A.; Ehrhardt, M.; Preußner, T.; Rädlein, E. The strength of uncoated and coated ultra-thin flexible glass under cyclic. AIMS Mater. Sci. 2024, 11, 343–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, K.; Dangate, M.S. Advancements in stretchable organic optoelectronic devices and flexible transparent conducting electrodes: Current progress and future prospects. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möckel, M.; Seel, M.; Schwind, G.; Engelmann, M. Temperature distribution and stress relaxation in glass under high temperature exposition. Glass Struct. Eng. 2025, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaiter, R.; Adamietz, F.; Désévédavy, F.; Strutynski, C.; Bailleul, D.; Smektala, F.; Buffeteau, T.; Vellutini, L.; Dussauze, M. Biofunctionalization of chalcogenide glass fiber to enhance real time and label free detection by mid infrared spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Lohia, P.; Dwivedi, D.K. Emerging phase change memory devices using non-oxide semiconducting glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2022, 597, 121874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraenkl, M.; Frumarova, B.; Podzemna, V.; Slang, S.; Benes, L.; Vlcek, M.; Wagner, T. How silver influences the structure and physical properties of chalcogenides glass (GeS2)50(Sb2S3)50. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2018, 499, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tveryanovich, Y.S.; Patrusheva, I.V.; Pazin, A.V.; Belyakova, N.V.; Tabolin, A.R. Electrical conductivity of glass Ag2Se–GeSe2–As2Se3 system. Fizika I Himiya Stekla. 1997, 23, 233–240. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Itoh, K. Network structure and cation environment in Ag2S-GeS2 glasses. Next Res. 2024, 1, 100049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezniuk, O.; Petrus’, I.I.; Zamurueva, O.; Piskach, L.V. Properties of glasses in the Ag2S–GeS2–As(Sb)2S3 systems. Sci. Bull. Uzhhorod Univ. Ser. Chem. 2023, 48, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tveryanovich, Y.S.; Fazletdinov, T.R.; Tverjanovich, A.S.; Fadin, Y.A.; Nikolskii, A.B. Features of Chemical Interactions in Silver Chalcogenides Responsible for Their High Plasticity. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2020, 90, 2203–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tveryanovich, Y.S.; Fazletdinov, T.R.; Tverjanovich, A.S.; Pankin, D.V.; Smirnov, E.V.; Tolochko, O.V.; Panov, M.S.; Churbanov, M.F.; Skripachev, I.V.; Shevelko, M.M. Increasing the Plasticity of Chalcogenide Glasses in the System Ag2Se–Sb2Se3–GeSe2. Chem. Mater. 2022, 34, 2743–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tveryanovich, Y.S.; Fazletdinov, T.R.; Tomaev, V.V. Peculiarities of the effect of silver chalcogenides on the glass-formation temperature of chalcogenide glasses with ionic conduction. Russ. J. Electrochem. 2023, 59, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisova, Z. Glassy Semiconductors; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1981; p. 506. [Google Scholar]

- Tveryanovich, Y.S. Some ideas in the chemistry and physics of chalcogenide glasses. In Proceedings of the International Year of Glass, St. Petersburg, Russia, 17 March 2022; pp. 147–157. [Google Scholar]

- Milman, Y.V.; Chugunova, S.I.; Goncharova, I.V.; Golubenko, A.A. Plasticity of materials determined by the indentation method. Usp. Fiz. Met. 2018, 19, 271–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaygorodsky, A.I. The structure of glass and methods of its study using X-ray structural analysis. Uspekhi Fiz. Nauk. 1938, 19, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaev, V.V.; Mazur, A.S.; Grevtsev, A.S. A study of the process of thermal oxidation of lead selenide by the NMR and XRD methods. Glass Phys. Chem. 2017, 43, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, T.E.; Ziman, J.M. A theory of the electrical properties of liquid metals. Philos. Mag. 1965, 11, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, S.R. Medium-range structural order in covalent amorphous solids. Nature 1991, 354, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, P.S.; Zeidler, A. Ordering on different length scales in liquid and amorphous materials. J. Stat. Mech. 2019, 11, 114006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, S.R. Extended-range order, interstitial voids and the first sharp diffraction peak of network glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1995, 182, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskell, P.H.; Eckersley, M.C.; Barnes, A.C.; Chieux, P. Medium-range order in the cation distribution of a calcium silicate glass. Nature 1991, 350, 675–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, P.S.; Martin, R.A.; Mason, P.E.; Cuello, G.J. Topological versus chemical ordering in network glasses at intermediate and extended length scales. Nature 2005, 435, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busse, L.E.; Nagel, S.R. Temperature dependence of the structure factor of As2Se3 glass up to the glass transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1981, 47, 1848–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.C. Topology of Covalent Non-Crystalline Solids: Medium-Range Order in Chalcogenide Alloys and a-Si(Ge). J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1981, 43, 37–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Červinka, L. Medium-Range Order in Amorphous Materials. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1988, 106, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, S.R. Origin of the first sharp diffraction peak in the structure factor of covalent glasses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1991, 67, 711–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchino, T.; Harrop, J.D.; Taraskin, S.N.; Elliott, S.R. Real and reciprocal space structural correlations contributing to the first sharp diffraction peak in silica glass. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 71, 014202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucovsky, G.; Phillips, J.C. Nano-regime Length Scales Extracted from the First Sharp Diffraction Peak in Non-crystalline SiO2 and Related Materials: Device Applications. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2010, 5, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, S.C.; Price, D.L. Physics of Disordered Materials; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1985; p. 77. [Google Scholar]

- Evertz, S.; Music, D.; Schnabel, V.; Bednarcik, J.; Schneider, J.M. Thermal expansion of Pd-based metallic glasses by ab initio methods and high energy X-ray diffraction. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagogianni, A.E.; Krausser, J.; Evenson, Z.; Samwer, K.; Zaccone, A. Unifying interatomic potential, g (r), elasticity, viscosity, and fragility of metallic glasses: Analytical model, simulations, and experiments. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2016, 2016, 084001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, P.S. Structure of liquids and glasses in the Ge–Se binary system. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2007, 353, 2959–2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassem, M.; Benmore, C.J.; Tverjanovich, A.; Bokova, M.; Khomenko, M.; Usuki, T.; Sokolov, A.; Fontanari, D.; Bereznev, S.; Ohara, K.; et al. Atomic Structure, Dynamics, Changes in Chemical Bonding and Semiconductor-Metal Transition in Sb2Se3: A Remarkable Material for Quantum Networks and Energy Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 17075–17095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, P.S.; Petri, I. Structure of glassy and liquid GeSe2. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2003, 15, S1509–S1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmore, C.J.; Salmon, P.S. Structure of fast-ion conducting chalcogenide glasses: The Ag-As-Se system. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1993, 156–158, 720–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitkova, M.; Wang, Y.; Boolchand, P. Dual Chemical Role of Ag as an Additive in Chalcogenide Glasses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 83, 3848–3851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bychkov, E.; Price, D.L.; Benmore, C.J.; Hannon, A.C. Ion transport regimes in chalcogenide and chalcohalide glasses: From the host to the cation-related network connectivity. Solid State Ion. 2002, 154–155, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, P.S.; Liu, J. The coordination environment of Ag and Cu in ternary chalcogenide glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1996, 205–207, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidler, A.; Salmon, P.S.; Whittaker, D.A.J. Structure of semiconducting versus fast-ion conducting glasses in the Ag–Ge–Se system. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 171401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penfold, I.T.; Salmon, P.S. Glass formation and short-range order in chalcogenide materials: The (Ag2S)x(As2S3)1−x (0 ≤ x ≤ 1) pseudobinary tie line. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1990, 64, 2164–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dejus, R.J.; Susman, S.; Volin, K.J.; Montague, D.G.; Price, D.L. Structure of vitreous Ag-Ge-Se. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1992, 143, 162–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Owens, A.P.; Pradel, A.; Hannon, A.C.; Ribes, M.; Elliott, S.R. Structure determination of Ag-Ge-S glasses using neutron diffraction. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bychkov, E.; Price, D.L.; Lapp, A. Universal trend of the Haven ratio in glasses: Origin and structural evidences from neutron diffraction and small-angle neutron scattering. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2001, 293–295, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseev, I.; Fontanari, D.; Sokolov, A.; Bokova, M.; Kassem, M.; Bychkov, E. Ionic conductivity and tracer diffusion in glassy chalcogenides. In World Scientific Reference of Amorphous Materials; World Scientific: Singapore, 2020; p. 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černošková, E.; Holubová, J.; Bureau, B.; Roiland, C.; Nazabal, V.; Todorov, R.; Černošek, Z. Thermoanalytical properties and structure of (As2Se3)100−x(Sb2Se3)x glasses by Raman and 77Se MAS NMR using a multivariate curve resolution approach. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2016, 432, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaseman, D.C.; Sen, S. A review of the application of 2D isotropic-anisotropic correlation NMR spectroscopy in structural studies of chalcogenide glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2021, 561, 120500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykina, K.; Bureau, B.; Le Polle, L.; Roiland, C.; Deschamps, M.; Pickardd, C.J.; Furet, E. A combined 77Se NMR and molecular dynamics contribution to the structural understanding of the chalcogenide glasses. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 17975–17982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furet, E.; Lecomte, A.; Le Coq, D.; Zeng, F.; Cormier, L.; Roiland, C.; Calvez, L. Structure of Ga-Sb-Se glasses by combination of 77Se NMR and neutron diffraction experiments with molecular dynamics. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2021, 557, 120574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marple, M.A.T.; Kaseman, D.C.; Hung, I.; Gan, Z.; Sen, S. Structure and physical properties of glasses in the system Ag2Se–Ga2Se3–GeSe2. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2016, 437, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukichev, A. Physical meaning of the stretched exponential Kohlrausch function. Phys. Lett. A 2019, 383, 2983–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazeer, H.; Bhaskaran, H.; Woldering, L.A.; Abelmann, L. Young’s modulus and residual stress of GeSbTe phase-change thin films. Thin Solid Film. 2015, 592 Pt A, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tveryanovich, Y.S.; Tverjanovich, A.S.; Tomaev, V.V.; Mazur, A.S.; Lun’kov, S.S.; Zaytseva, S.A.; Bychkov, E. Relationship of Metallophilic Interactions with Structural and Mechanical Properties of (1−x) (0.73GeSe2-0.27Sb2Se3)-xAg2Se Glasses. Compounds 2025, 5, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/compounds5040056

Tveryanovich YS, Tverjanovich AS, Tomaev VV, Mazur AS, Lun’kov SS, Zaytseva SA, Bychkov E. Relationship of Metallophilic Interactions with Structural and Mechanical Properties of (1−x) (0.73GeSe2-0.27Sb2Se3)-xAg2Se Glasses. Compounds. 2025; 5(4):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/compounds5040056

Chicago/Turabian StyleTveryanovich, Yuriy S., Andrey S. Tverjanovich, Vladimir V. Tomaev, Anton S. Mazur, Svyatoslav S. Lun’kov, Sonya A. Zaytseva, and Eugene Bychkov. 2025. "Relationship of Metallophilic Interactions with Structural and Mechanical Properties of (1−x) (0.73GeSe2-0.27Sb2Se3)-xAg2Se Glasses" Compounds 5, no. 4: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/compounds5040056

APA StyleTveryanovich, Y. S., Tverjanovich, A. S., Tomaev, V. V., Mazur, A. S., Lun’kov, S. S., Zaytseva, S. A., & Bychkov, E. (2025). Relationship of Metallophilic Interactions with Structural and Mechanical Properties of (1−x) (0.73GeSe2-0.27Sb2Se3)-xAg2Se Glasses. Compounds, 5(4), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/compounds5040056