Sodium Nitrite-Related Fatalities: Are We Facing a New Trend? Case Report and Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Description

2.1. Circumstantial Data

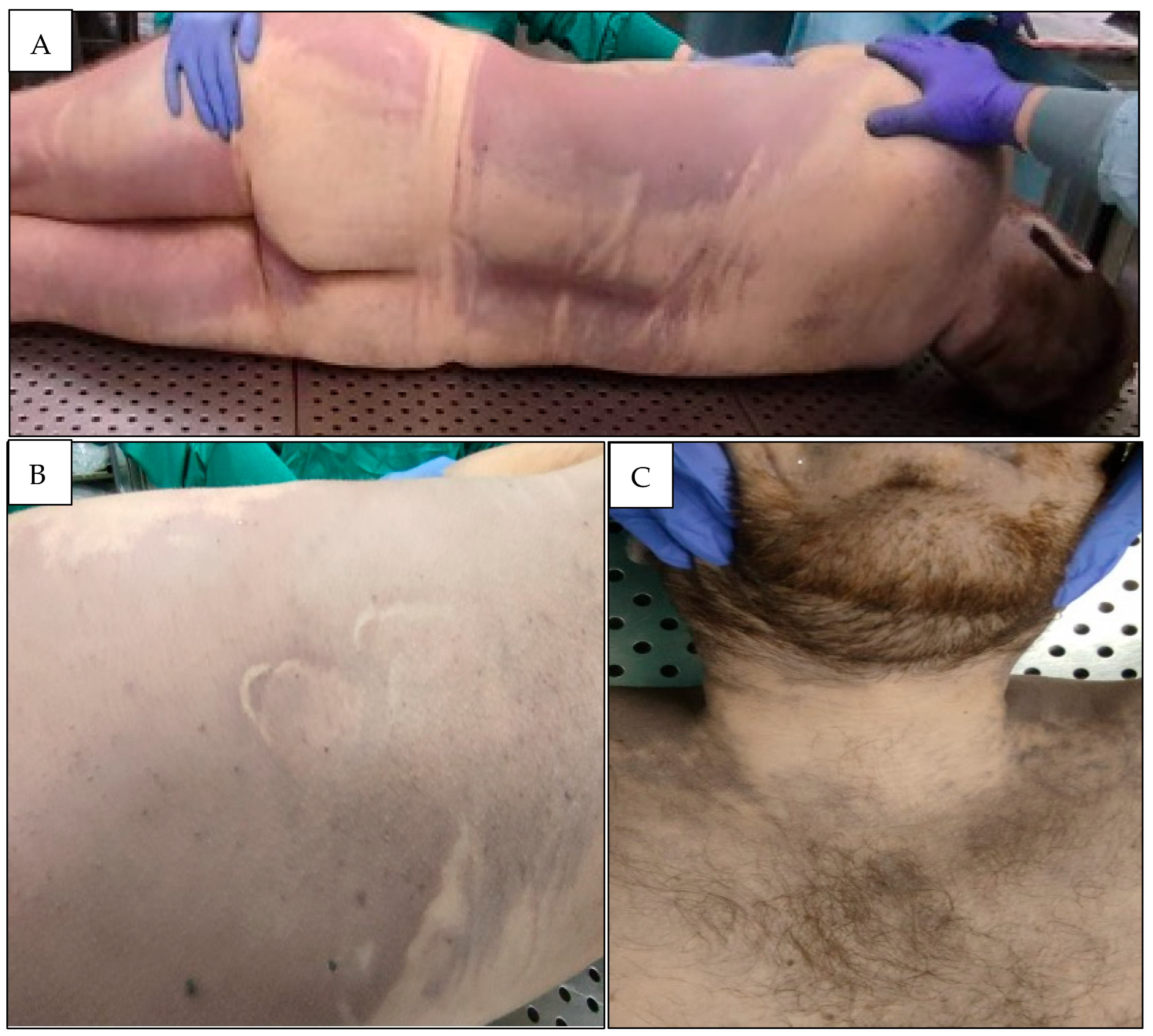

2.2. Autopsy Findings

2.3. Toxicological Investigations

3. Literature Review

3.1. Search Strategy

3.2. Review Results

3.3. Limitations and Risk of Bias

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Maiese, A.; Gitto, L.; dell’Aquila, M.; Bolino, G. A peculiar case of suicide enacted through the ancient Japanese ritual of Jigai. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2014, 35, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Paola, L.; Tripi, D.; Napoletano, G.; Marinelli, E.; Montanari Vergallo, G.; Zaami, S. Violence against Women within Italian and European Context: Italian “Pink Code”—Major Injuries and Forensic Expertise of a Socio-Cultural Problem: A Narrative Review. Forensic Sci. 2024, 4, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Brink, B.; Roodnat, R.; Rippe, R.C.A.; Cherniak, A.D.; van Lieshout, K.; Helder, S.G.; Braam, A.W.; Schaap-Jonker, H. Religiosity, Spirituality, Meaning-Making, and Suicidality in Psychiatric Patients and Suicide Attempters: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2024, 32, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polidori, L.; Sarli, G.; Berardelli, I.; Pompili, M.; Baldessarini, R.J. Risk of suicide attempt with gender diversity and neurodiversity. Psychiatry Res. 2024, 333, 115632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher, L.; Oquendo, M.A. Suicide: An Overview for Clinicians. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 107, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klonsky, E.D.; Pachkowski, M.C.; Shahnaz, A.; May, A.M. The three-step theory of suicide: Description, evidence, and some useful points of clarification. Prev. Med. 2021, 152 Pt 1, 106549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghirini, S.; Vichi, M. Caratteristiche e andamento temporale della mortalità per suicidio in Italia: Uno studio descrittivo sugli ultimi 30 anni. Boll. Epidemiol. 2020, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durão, C.; Pedrosa, F.; Dinis-Oliveira, R.J. A fatal case by a suicide kit containing sodium nitrite ordered on the internet. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2020, 73, 101989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, D.E.; Looman, K.B.; Topmiller, R.G. Fatal methemoglobinemia in three suicidal sodium nitrite poisonings. J. Forensic Sci. 2021, 66, 1570–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szórádová, A.; Hojsík, D.; Zdarílek, M.; Valent, D.; Nižnanský, Ľ.; Kovács, A.; Hokša, R.; Šidlo, J. Modern suicide trend from internet. Leg. Med. 2024, 67, 102384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbo, S.; Spanò, M.; Albano, G.D.; Buscemi, R.; Malta, G.; Argo, A. A fatal suicidal sodium nitrite ingestion determined six days after death. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2023, 98, 102576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padovano, M.; Aromatario, M.; D’Errico, S.; Concato, M.; Manetti, F.; David, M.C.; Scopetti, M.; Frati, P.; Fineschi, V. Sodium Nitrite Intoxication and Death: Summarizing Evidence to Facilitate Diagnosis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, D.; Živković, V.; Lukić, V.; Nikolić, S. Sodium nitrite food poisoning in one family. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2019, 15, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/IT/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L_202302108 (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Varlet, V.; Ryser, E.; Augsburger, M.; Palmiere, C. Stability of postmortem methemoglobin: Artifactual changes caused by storage conditions. Forensic Sci. Int. 2018, 283, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaubrytė, S.S.; Chmieliauskas, S.; Salyklytė, G.; Laima, S.; Vasiljevaitė, D.; Stasiūnienė, J.; Petreikis, P.; Badaras, R. Fatal Outcome of Suicidal Multi-Substance Ingestion Involving Sodium Nitrate and Nitrite Toxicity: A Case Report and Literature Review. Acta Medica Litu. 2025, 32, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, S.; Yang, W.; Sim, J. Determination of nitrite and nitrate in postmortem whole blood samples of 10 sodium nitrite poisoning cases: The importance of nitrate in determining nitrite poisoning. Forensic Sci. Int. 2022, 335, 111279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andelhofs, D.; Van Den Bogaert, W.; Lepla, B.; Croes, K.; Van de Voorde, W. Suicidal sodium nitrite intoxication: A case report focusing on the postmortem findings and toxicological analyses-review of the literature. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2024, 20, 949–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, M.; Schmoldt, A.; Andresen-Streichert, H.; Iwersen-Bergmann, S. Revisited: Therapeutic and toxic blood concentrations of more than 1100 drugs and other xenobiotics. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudan, A.; Repplinger, D.; Lebin, J.; Lewis, J.; Vohra, R.; Smollin, C. Severe Methemoglobinemia and Death From Intentional Sodium Nitrite Ingestions. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 59, e85–e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Jang, E.J.; Yum, H.; Choi, Y.S.; Hong, J. Unintentional mass sodium nitrite poisoning with a fatality. Clin. Toxicol. 2017, 55, 678–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickey, T.B.M.; MacNeil, J.A.; Hansmeyer, C.; Pickup, M.J. Fatal methemoglobinemia: A case series highlighting a new trend in intentional sodium nitrite or sodium nitrate ingestion as a method of suicide. Forensic Sci. Int. 2021, 326, 110907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedhai, Y.R.; Atreya, A.; Basnyat, S.; Phuyal, P.; Pokhrel, S. The use of sodium nitrite for deliberate self-harm, and the online suicide market: Should we care? Med.-Leg. J. 2022, 90, 79–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, L.; Wills, S.; van den Heuvel, C.; Humphries, M.; Byard, R.W. Increasing use of sodium nitrite in suicides-an emerging trend. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2022, 18, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikin, L.J.; Ho, J.; Morley, S.R.; Ahluwalia, A.; Smith, P.R. Sodium nitrite poisoning: A series of 20 fatalities in which post-mortem blood nitrite and nitrate concentrations are reported. Forensic Sci. Int. 2023, 345, 111610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugelli, V.; Tarozzi, I.; Manetti, A.C.; Stefanelli, F.; Di Paolo, M.; Chericoni, S. Four cases of sodium nitrite suicidal ingestion: A new trend and a relevant Forensic Pathology and Toxicology challenge. Leg. Med. 2022, 59, 102146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taus, F.; Pigaiani, N.; Bortolotti, F.; Mazzoleni, G.; Brevi, M.; Tagliaro, F.; Gottardo, R. Direct and specific analysis of nitrite and nitrate in biological and non-biological samples by capillary ion analysis for the rapid identification of fatal intoxications with sodium nitrite. Forensic Sci. Int. 2021, 325, 110855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.; Yeon, S.H.; Jung, J.; Na, J.Y. An autopsy case of sodium nitrite-induced methemoglobinemia with various post-mortem analyses. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2021, 17, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desrosiers, N.A.; Chow, B.L.C. Impact of methemoglobin on carboxyhemoglobin saturation measurement in fatal sodium nitrate and sodium nitrite cases. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2023, 47, 750–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, C.; Mernissi, T.; Duvauchelle, B.; Bennis, Y.; Quinton-Bouvier, M.C.; Masmoudi, K.; Bodeau, S.; Quero, A.; Molinié, G.; Bassard, S.; et al. Un nouveau cas d’intoxication au nitrite de sodium au CHU Amiens-Picardie: Un phénomène qui prend de l’ampleur? A new case of sodium nitrite poisoning at the Amiens-Picardie University Hospital: A growing phenomenon? Toxicol. Anal. Clin. 2023, 35, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomsia, M.; Głaz, M.; Nowicka, J.; Szczepański, M. Sodium nitrite detection in costal cartilage and vitreous humor—Case report of fatal poisoning with sodium nitrite. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2021, 81, 102186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mun, S.H.; Park, G.J.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, Y.M.; Chai, H.S.; Kim, S.C. Two cases of fatal methemoglobinemia caused by self-poisoning with sodium nitrite: A case report. Medicine 2022, 101, e28810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wettstein, Z.S.; Yarid, N.A.; Shah, S. Fatal methaemoglobinemia due to intentional sodium nitrite ingestion. BMJ Case Rep. 2022, 15, e252954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, D.S.; Gao, Y.; Bao, X.J.; Tang, Y.J.; Lin, Y.L.; Xu, J.X.; Zhang, J.N.; Liu, B.W.; Kang, K. Acquired methemoglobinemia in a third trimester puerpera and her premature infant with sodium nitrite poisoning: A case report. World J. Clin. Cases 2024, 12, 5151–5158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.O.; Lewander, W.J.; Woolf, A.D. Methemoglobinemia: Etiology, pharmacology, and clinical management. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1999, 34, 646–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iolascon, A.; Bianchi, P.; Andolfo, I.; Russo, R.; Barcellini, W.; Fermo, E.; Toldi, G.; Ghirardello, S.; Rees, D.; Van Wijk, R.; et al. Recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of methemoglobinemia. Am. J. Hematol. 2021, 96, 1666–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinheiro, S.; Carvalho, F.; Carmo, H. Self-poisoning by sodium nitrite ingestion: Investigating toxicological mechanisms in vitro. Toxicol. Lett. 2025, 409, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, S.D.; Tweet, M.S.; Wahl, M.S. Rising incidence and high mortality in intentional sodium nitrite exposures reported to US poison centers. Clin. Toxicol. 2021, 59, 1264–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallocci, M.; Passalacqua, P.; Zanovello, C.; Coppeta, L.; Ferrari, C.; Milano, F.; Gratteri, S.; Gratteri, N.; Treglia, M. Forensic Characterisation of Complex Suicides: A Literature Review. Forensic Sci. 2024, 4, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallocci, M.; Treglia, M.; Passalacqua, P.; Guidato, F.; Milano, F.; Sacchetti, G.; Marsella, L.T. Forensic analysis of planned and unplanned complex suicides: A case series. Aust. J. Forensic Sci. 2025, 57, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiwata, Y.; Arima, Y.; Fujishiro, M.; Ohtawa, T.; Izawa, H.; Sobue, H.; Taira, R.; Umezawa, H.; Lee, X.-P.; Sato, K. Long-term Storage of Blood at Freezing Temperatures for Methemoglobin Determination: Comparison of Storage with and without a Cryoprotectant. Showa Univ. J. Med. Sci. 2008, 20, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

| Central Blood | Urine | Peripheral Blood | Therapeutic Range (mg/L) | Toxic Range (mg/L) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7-aminoclonazepam (ng/mL) | n.p. | 195 | 75 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Citalopram (mg/L) | 0.514 | 0.109 | n.p. | 0.05–0.11 | 0.22–2.45 |

| Et-OH (g/L) | n.d. | n.d | n.d. | n.a | 1000–2000 |

| % Methemoglobin | >30% | n.p. | n.p. | n.a | 25–30% |

| Nitrites (NO2−), nitrates (NO3−) (µmol/L) | 9515 | n.p. | n.p. | 0.1–10 [21] | n.a. |

| Author | Year | Cases/Sex | Age | Autopsy Findings | Toxicology (Nitrite/Nitrate) | MetHb Range | Type of Event |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Durao et al. [9] | 2020 | 1 M | 37 | External examination: Intense scleral congestion and cyanosis of the extremities, brown-gray-blue-red hypostasis. Autopsy: Tardieu petechiae and intense polyvisceral congestion; chocolate brown color of the blood, pulmonary edema, and coronary artery disease. | Sample: femoral blood and gastric content; methodology: spectrophotometry | N.A. | Suicide |

| Dean et al. [10] | 2020 | 2 M, 1 F | 22–39 | External examination: gray hypostasis; autopsy: brown color of blood. | N.A. | 62%; 33%; 44% | Suicide |

| Szoradova et al. [11] | 2024 | 2 M, 2 F | 19–33 | External examination: grey-purple-brown-blue discoloration of the skin. Autopsy: dark brown color of the blood; swelling of the brain and lungs, blood effusions under the pleura, and dark red-gray-brown coloring of the organs. | Sample: only blood in one case, with also urine, liver, kidneys, spleen, brain, lungs, stomach content in the other two cases, and also with vitreous humor in the last case; methodology: isotachophoresis with a conductivity detector (1 case) | 20.24–71.4%; >70% | Suicide |

| Zerbo et al. [12] | 2023 | 1 F | 20 | External examination: Labial and subungual cyanosis, grayish-purple hypostasis, dried brownish-green liquid around nasal and oral orifices. Autopsy: subpleural petechiae, brownish fluid in the pleural cavities, congested and edematous lungs and diffuse visceral congestion, edema and hemorrhagic petechiae of the laryngeal, the glottis, and tracheal submucosa and green-brownish foamy liquid in the tracheal lumen. | N.A. | 12.8% | Suicide |

| Cvetkovic et al. [14] | 2018 | 1 M | 70 | External examination: dark bluish red hypostasis with vibices. | Sample: blood, gastric content, liver, and kidney mixture | 9.87% | Accidental ingestion |

| Kim et al. [18] | 2022 | 8 M, 2 F | 21–35 | N.A. | Sample: peripheral blood and gastric content; methodology: ion chromatography | N.A. | 9 suicide; 1 suspected adverse effect of vaccine |

| Andelhofs et al. [19] | 2023 | 1 F | 18 | External examination: Gray-brownish hypostasis, lips and fingernails cyanosis. Autopsy: pulmonary edema with brownish foam in the airways, mild cerebral edema, and congestions of the visceral organs, “chocolate” brown blood. | Sample: liquid stomach contents and serum isolated from peripheral blood; methodology: nitrite sticks and spectrophotometry | 35% | Suicide |

| Lee C. et al. [22] | 2017 | 1 M, 4 F | 58–76 | N.A. | Sample: arterial and peripheral blood, urine, and gastric content | 0.1–5.7% | Accidental ingestion |

| Hickey et al. [23] | 2021 | 21 M, 7 F | 20–86 | External examination: grayish-brown, purple-brown, red-purple-brown, dark purple/blue, purple-gray, dusky gray, gray blue, purple-gray, gray, gray-green-blue, ash-colored hypostasis. Autopsy: brown blood. | N.A. | 6–92% | 20 suicides; 1 drug causing MetHb; 1 complication of alcoholism; 4 undetermined; 2 unascertained |

| Sedhai et al. [24] | 2021 | 1 M | 37 | N.A. | Arterial blood | >10% | Suicide attempt |

| Stephenson et al. [25] | 2022 | 8 M, 2 F | 22–74 | External examination: Blue-gray hypostasis. Autopsy: brown color of blood, pulmonary edema. | Sample: urine, vitreous humor and gastric content; methodology: urine dipstick | 87.5% (1 case) | Suicide |

| Hikin et al. [26] | 2023 | 12 M, 8 F | 14–49 | External examination: gray hypostasis. | Sample: blood; methodology: ozone-based chemiluminescence | >70% (1 case) | 19 suicides, 1 not defined |

| Bugelli et al. [27] | 2022 | 3 M, 1 F | 27–51 | External examination: Grayish-purple-blue hypostasis, subungual cyanosis. Autopsy: pulmonary edema, diffuse visceral congestion, brownish blood, acute emphysema, brain edema, and a recent microscopic subarachnoid hemorrhage focus, stretch cardiac myofibers with fragmentation. | Sample: peripheral blood and urine; methodology: high-performance liquid chromatography and ion chromatography | >30% | Suicide |

| Taus et al. [28] | 2021 | 2 M | 28–33 | External examination: Cyanosis of hands, lips, and fingernail beds, brown-red-gray hypostasis. Autopsy: multi-organ congestion, cerebral and pulmonary edema. | Sample: blood; methodology: capillary electrophoresis | N.A. | Suicide |

| Hwang et al. [29] | 2021 | 1 M | 28 | External examination: Reddish-purple hypostasis; dark brown face; cyanotic nails; bright red oral mucosa. Autopsy: congestion of the internal organs and pulmonary edema. | Sample: peripheral blood and cardiac blood; pericardial and cerebrospinal fluid; methodology: ion chromatography | 33% (PM inspection) 26% (autopsy) | Suicide |

| Desrosiers et al. [30] | 2023 | 2 M, 2 F | 20–45 | External examination: Brown discoloration of the skin, purple-gray discoloration of the lips. | N.A. | 17.4–89% | Suicide |

| Andrè et al. [31] | 2022 | 1 F | 31 | External examination: cyanosis of the extremities. | Sample: aqueous solution made from the unknown white powder; methodology: ion chromatography | 20.5% | Suicide |

| Tomsia et al. [32] | 2021 | 1 M | 23 | Eternal examination: Dark purple discoloration of the upper and lower lips, cyanosis of the fingers. Autopsy: Gray-yellowish-brown mucous membrane of the trachea. | Sample: femoral blood, urine, vitreous humor, gastric contents, liver, kidney, and costal cartilage; methodology: Griess method and spectrophotometry | N.A. | Suicide |

| Mun et al. [33] | 2022 | 1 M | 20 | N.A. | N.A. | 90.3% | Suicide |

| Wettestein et al. [34] | 2022 | 1 M | 25 | External examination: blue-gray hypostasis. | N.A. | N.A. | Suicide |

| Fei et al. [35] | 2024 | 1F (newborn) | N.A. | N.A. | 3.3% | Accidental ingestion |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caparrelli, V.; Pallocci, M.; Tittarelli, R.; Russo, C.; Donato, L.; Ponzani, F.; Passalacqua, P.; Milano, F.; Treglia, M. Sodium Nitrite-Related Fatalities: Are We Facing a New Trend? Case Report and Literature Review. Forensic Sci. 2025, 5, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5030042

Caparrelli V, Pallocci M, Tittarelli R, Russo C, Donato L, Ponzani F, Passalacqua P, Milano F, Treglia M. Sodium Nitrite-Related Fatalities: Are We Facing a New Trend? Case Report and Literature Review. Forensic Sciences. 2025; 5(3):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5030042

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaparrelli, Valentina, Margherita Pallocci, Roberta Tittarelli, Carmelo Russo, Laura Donato, Francesca Ponzani, Pierluigi Passalacqua, Filippo Milano, and Michele Treglia. 2025. "Sodium Nitrite-Related Fatalities: Are We Facing a New Trend? Case Report and Literature Review" Forensic Sciences 5, no. 3: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5030042

APA StyleCaparrelli, V., Pallocci, M., Tittarelli, R., Russo, C., Donato, L., Ponzani, F., Passalacqua, P., Milano, F., & Treglia, M. (2025). Sodium Nitrite-Related Fatalities: Are We Facing a New Trend? Case Report and Literature Review. Forensic Sciences, 5(3), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5030042