Optimizing Organic Photovoltaic Efficiency Through Controlled Doping of ZnS/Co Nanoparticles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods Section

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of ZnS/Co NPs

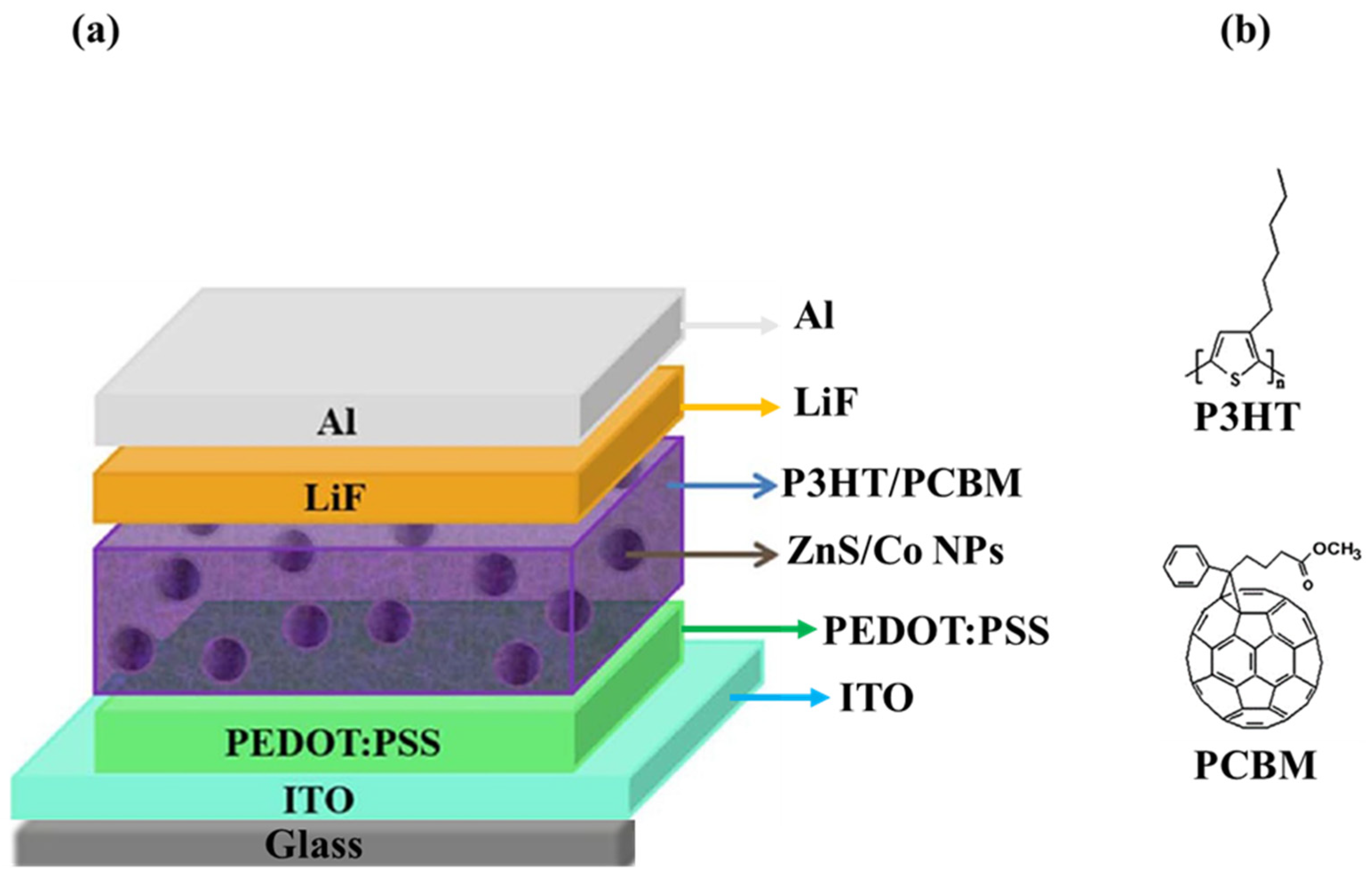

2.3. Device Fabrication of ZnS/Co NPs

2.4. Device Characterization Section

3. Results and Discussion Section

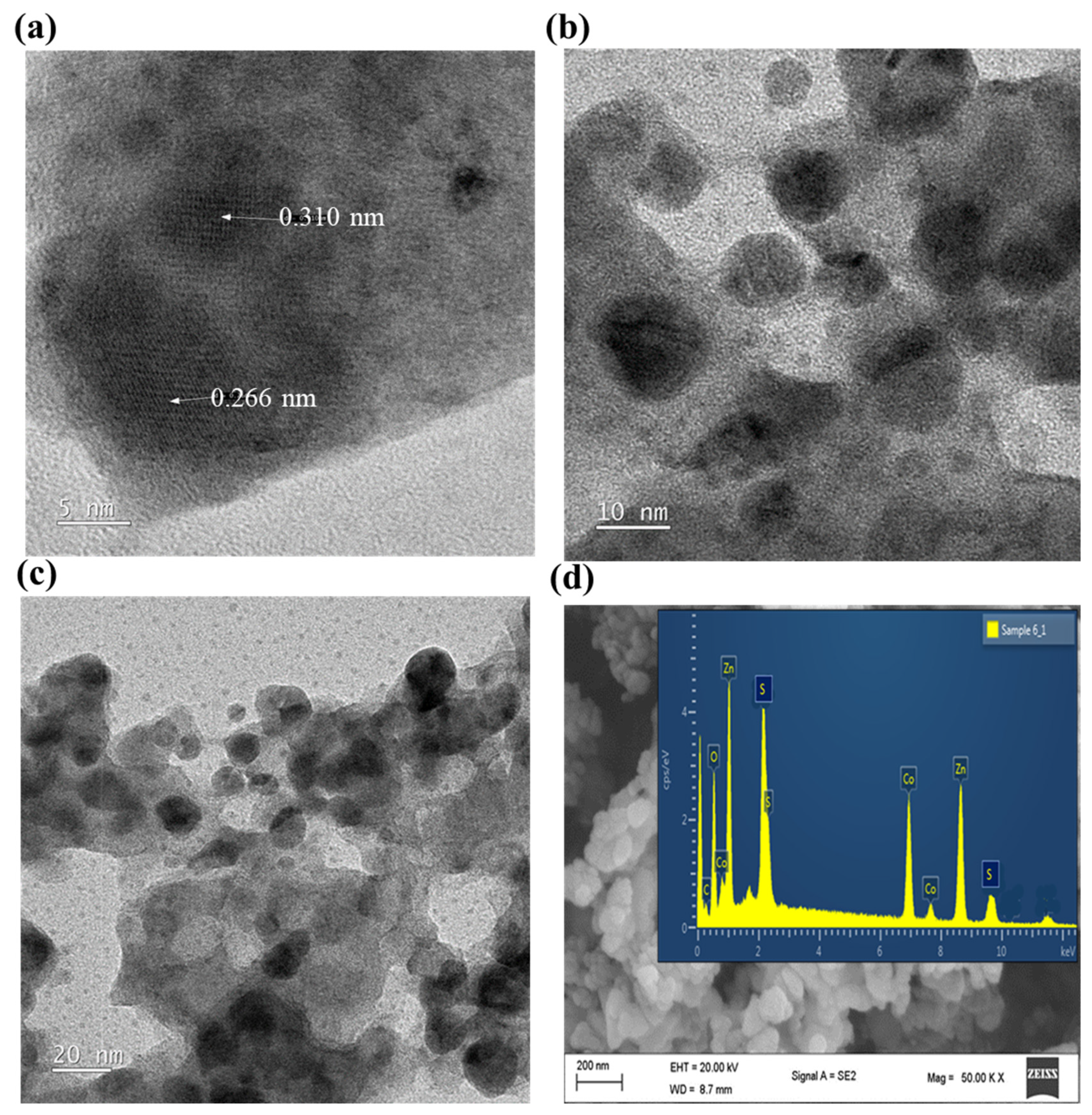

3.1. Morphological and Structural Characterization of Cobalt-Doped ZnS NPs

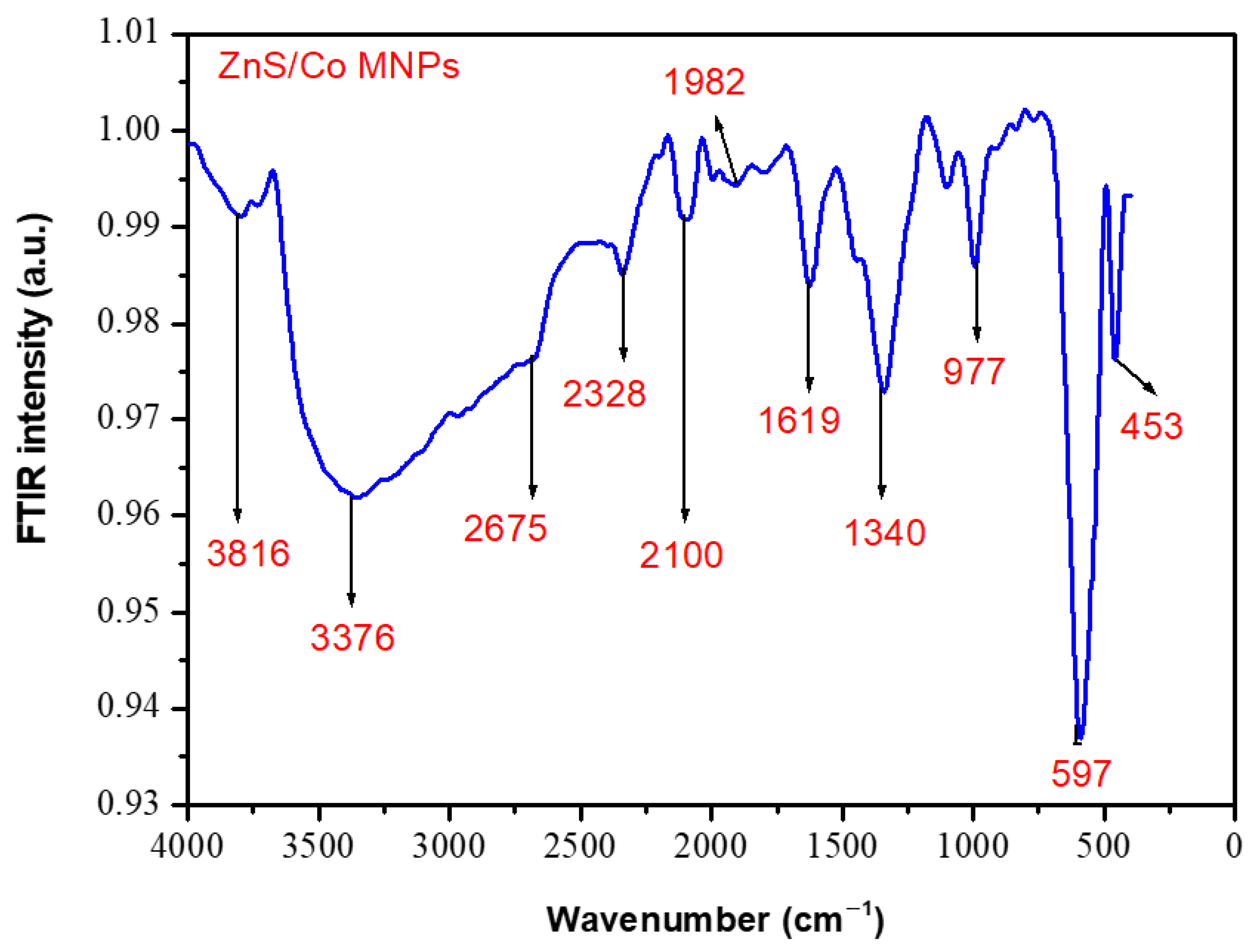

3.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrophotometer of ZnS/Co NPs

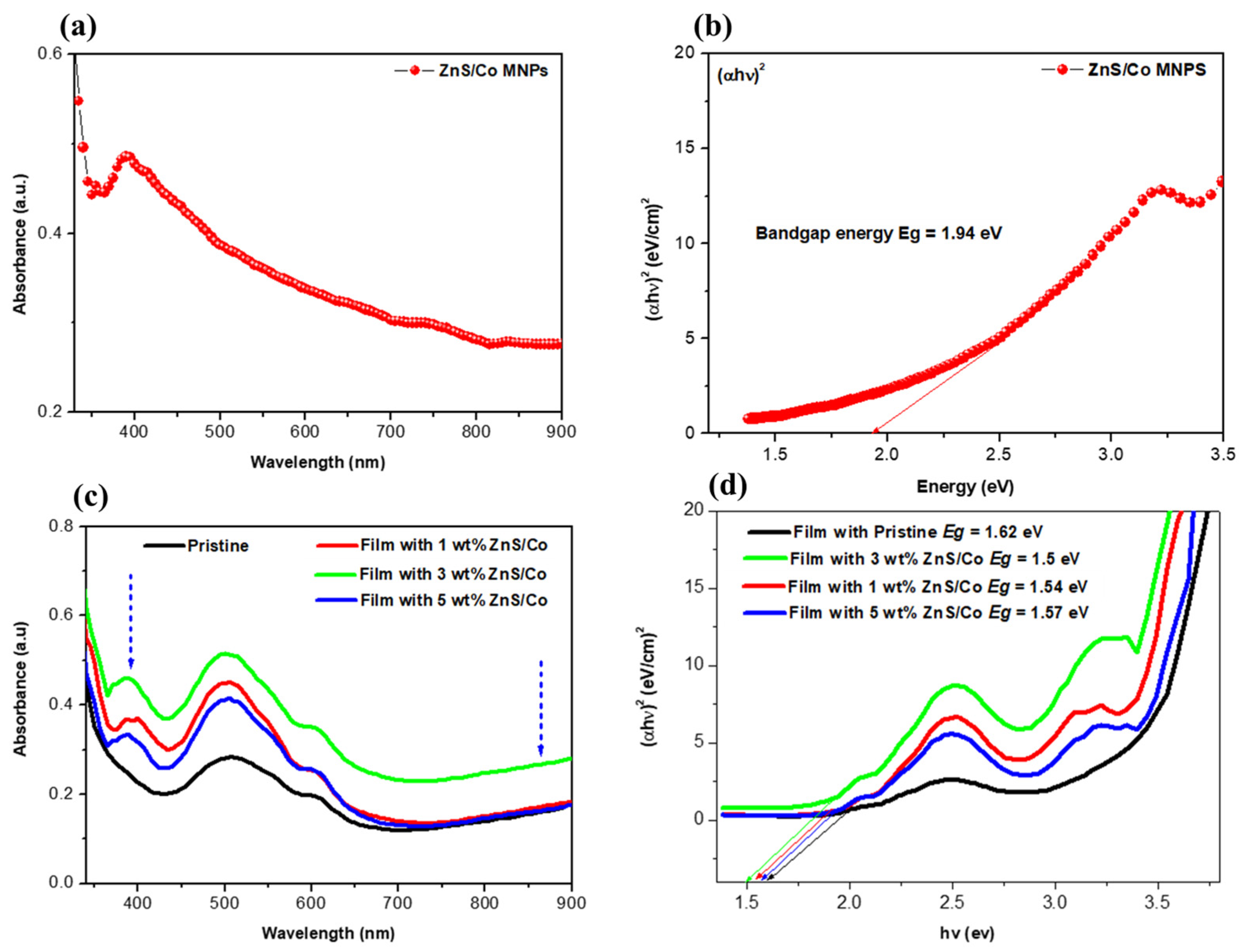

3.3. Optical Absorption of the Photoactive Films

3.4. Electrical Properties of the Photoactive Films

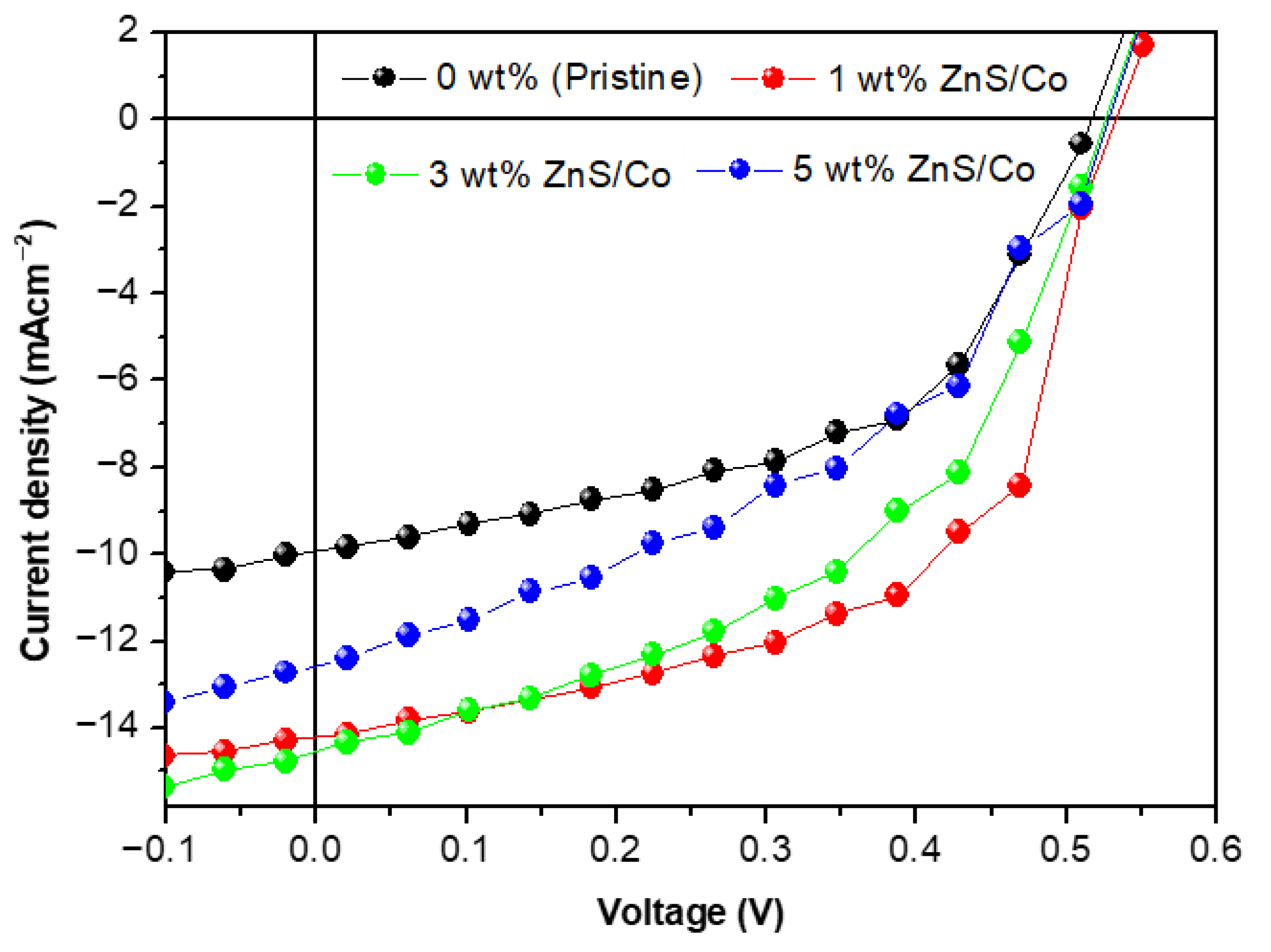

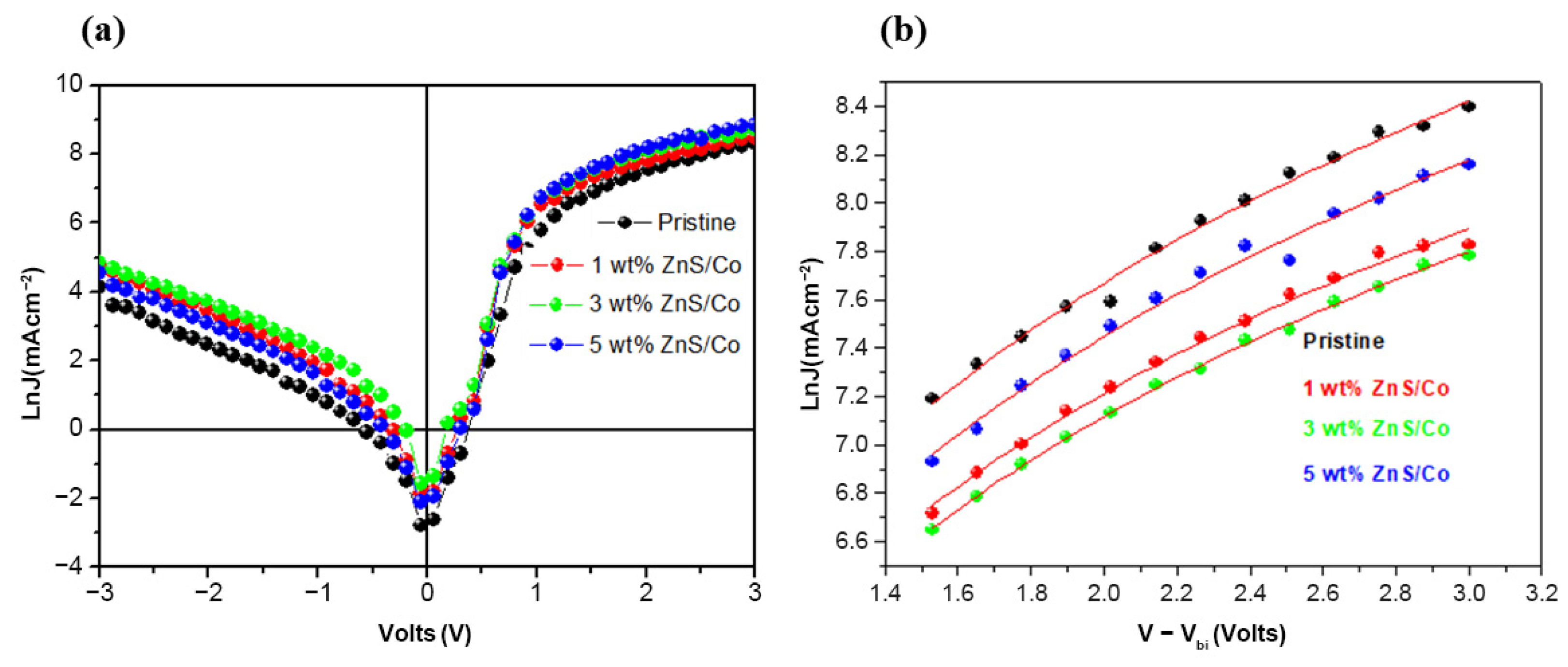

3.5. Charge Transport Properties of the Photoactive Films

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wadsworth, A.; Moser, M.; Marks, A.; Little, M.S.; Gasparini, N.; Brabec, C.J.; Baran, D.; McCulloch, I. Critical review of the molecular design progress in non-fullerene electron acceptors towards commercially viable organic solar cells. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 1596–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ike, J.N.; Mola, G.T.; Taziwa, R.T. Review on Indacenodithiophene (IDT) and Perylene Diimides (PDIs) Based Non-Fullerene Acceptors in Organic Solar Cells: Progress and Challenges. Chem. Afr. 2025, 8, 2687–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Yao, H.; Zhang, J.; Xian, K.; Zhang, T.; Hong, L.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Ma, K.; An, C.; et al. Single-junction organic photovoltaic cells with approaching 18% efficiency. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1908205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Wang, J.; Ma, X.; Gao, J.; Xu, C.; Yang, K.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, F. A critical review on semitransparent organic solar cells. Nano Energy 2020, 78, 105376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; He, Z.; Liu, X.; Xin, J.; Geng, Z.; Yang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Duan, M.; Qin, B.; et al. Temporally stepwise crystallization via dual-additive orchestration: Resolving the crystallinity-domain size paradox for high-efficiency organic photovoltaics. J. Energy Chem. 2025, 112, 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, S.; Ren, J.; Gao, M.; Bi, P.; Ye, L.; Hou, J. Molecular design of a non-fullerene acceptor enables a P3HT-based organic solar cell with 9.46% efficiency. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 2864–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Feng, K.; Lee, Y.W.; Woo, H.Y.; Zhang, G.; Peng, Q. Subtle polymer donor and molecular acceptor design enable efficient polymer solar cells with a very small energy loss. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 907570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, L.; Guo, C.; Xiao, J.; Liu, C.; Chen, C.; Xia, W.; Gan, Z.; Cheng, J.; Zhou, J.; et al. π-extended nonfullerene acceptor for compressed molecular packing in organic solar cells to achieve over 20% efficiency. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 12011–12019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Sun, S.; Xu, R.; Liu, F.; Miao, X.; Ran, G.; Liu, K.; Yi, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, X. Non-fullerene acceptor with asymmetric structure and phenyl-substituted alkyl side chain for 20.2% efficiency organic solar cells. Nat. Energy 2024, 9, 975–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Zhan, X. Versatile third components for efficient and stable organic solar cells. Mater. Horiz. 2015, 2, 462–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ike, J.N.; Nqoro, X.; Mola, G.T.; Taziwa, R.T. Controlling the Concentration of Copper Sulfide Doped with Silver Metal Nanoparticles as a Mechanism to Improve Photon Harvesting in Polymer Solar Cells. Processes 2025, 13, 2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.Y.; Ogundele, A.K.; Hamed, M.S.; Tegegne, N.A.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, G.; Mola, G.T. Application of cobalt-sulphide to suppress charge recombinations in polymer solar cell. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2025, 185, 108917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notarianni, M.; Vernon, K.; Chou, A.; Aljada, M.; Liu, J.; Motta, N. Plasmonic effect of gold nanoparticles in organic solar cells. Sol. Energy 2014, 106, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oseni, S.O.; Mola, G.T. Bimetallic nanocomposites and the performance of inverted organic solar cell. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 172, 660–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, K.; Oshikiri, T.; Sun, Q.; Shi, X.; Misawa, H. Solid-state plasmonic solar cells. Chem. Rev. 2017, 118, 2955–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulat, S.A.; Hone, F.G.; Bekri, N.; Tegegne, N.A. Improving the light harvest of plasmonic based organic solar cells by utilizing dielectric core–Shells. Plasmonics 2025, 20, 4007–4019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coviello, V.; Forrer, D.; Amendola, V. Recent developments in plasmonic alloy nanoparticles: Synthesis, modelling, properties and applications. ChemPhysChem 2022, 23, e202200136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.Y.; Ike, J.N.; Hamed, M.S.; Mola, G.T. Silver decorated magnesium doped photoactive layer for improved collection of photo-generated current in polymer solar cell. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2023, 140, e53697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedeji, M.A.; Hamed, M.S.; Mola, G.T. Light trapping using copper decorated nano-composite in the hole transport layer of organic solar cell. Sol. Energy 2020, 203, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlamini, M.W.; Hamed, M.S.; Mbuyise, X.G.; Mola, G.T. Improved energy harvesting using well-aligned ZnS nanoparticles in bulk-heterojunction organic solar cell. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2020, 31, 9415–9422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.T.; Anoop, C.S.; Vinod, G.A.; Reddy, V.S. Efficiency enhancement in polymer solar cells using combined plasmonic effects of multi-positional silver nanostructures. Org. Electron. 2020, 86, 105872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Jiang, R.; You, P.; Zhu, X.; Wang, J.; Yan, F. Au/Ag core–shell nanocuboids for high-efficiency organic solar cells with broadband plasmonic enhancement. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 898–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, P.; Singh, A.; Datt, R.; Gupta, V.; Arya, S. Realization of inverted organic solar cells by using sol-gel synthesized ZnO/Y2O3 core/shell nanoparticles as electron transport layer. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2020, 10, 1744–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.; Yiu, W.K.; Foo, Y.; Shen, Q.; Bejaoui, A.; Zhao, Y.; Gokkaya, H.C.; Djuris, A.B.; Zapien, J.A.; Chan, W.K.; et al. Enhanced performance of PTB7: PC71BM solar cells via different morphologies of gold nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 20676–20684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollu, S.R.; Sharma, R.; Srinivas, G.; Kundu, S.; Gupta, D. Effects of incorporation of copper sulfide nanocrystals on the performance of P3HT: PCBM based inverted solar cells. Org. Electron. 2014, 15, 2518–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardozo, O.; Farooq, S.; Farias, P.M.; Fraidenraich, N.; Stingl, A.; Araujo, R.E.D. Zinc oxide nanodiffusers to enhance p3ht: Pcbm organic solar cells performance. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2022, 33, 3225–3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, P.S.; Sangeetha, T.; Rajakarthihan, S.; Vijayalaksmi, R.; Elangovan, A.; Arivazhagan, G. XRD structural studies on cobalt doped zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized by coprecipitation method: Williamson-Hall and size-strain plot approaches. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2020, 595, 412342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synthesis, S.I. Synthesis, properties and applications of semiconductor nanostructured zinc sulfide. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2019, 88, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy-Benítez, J.A.; Colina-Ruiz, R.A.; Lezama-Pacheco, J.S.; de León, J.M.; Espinosa-Faller, F.J. Local atomic structure and lattice defect analysis in heavily Co-doped ZnS thin films using X-ray absorption fine structure spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2020, 136, 109154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Javaid, N.; Rafiq, A.; Samreen, A.; Riaz, S.; Naseem, S. Outstanding performance of Co-doped ZnS nanoparticles used as nanocatalyst for synthetic dye degradation. Results Mater. 2024, 24, 100628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, J.K.; Hammad, T.M.; Kuhn, S.; Draaz, M.A.; Hejazy, N.K.; Hempelmann, R. Structural and optical properties of Co-doped ZnS nanoparticles synthesized by a capping agent. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2014, 25, 2177–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranmanesh, P.; Saeednia, S.; Nourzpoor, M. Characterization of ZnS nanoparticles synthesized by co-precipitation method. Chin. Phys. B 2015, 24, 046104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, W.S.; Ezzeldien, M.; Alshammari, A.H.; Alshammari, K.; Alhassan, S.; Hadia, N.M.A. Facile hydrothermal synthesis and characterization of novel Co-doped ZnS nanoparticles with superior physical properties. Opt. Mater. 2024, 157, 116345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; MacKenzie, R.C.; Würfel, U.; Neher, D.; Kirchartz, T.; Deibel, C.; Saladina, M. Transport resistance dominates the fill factor losses in record organic solar cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2025, 2405889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavifar, S.M.; Ghasemi, M.; Haidari, G. Near and far-field plasmonic enhancement from thermally evaporated ag nanostructures in polymer photovoltaic cells: Simulation and experimental study. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2020, 10, 1735–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.G.; Pantelides, S.T. Theory of space charge limited currents. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 266602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Fu, S.; Wang, L.; Ren, M.; Li, H.; Han, S.; Lu, X.; Lu, F.; Tong, J.; Li, J. Efficient organic solar cells by modulating photoactive layer morphology with halogen-free additives. Opt. Mater. 2023, 137, 113503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waketola, A.G.; Hone, F.G.; Geldasa, F.T.; Genene, Z.; Mammo, W.; Tegegne, N.A. Enhancing the performance of wide-bandgap polymer-based organic solar cells through silver nanorod integration. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 8082–8091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Device Architecture | NPs | NPs Location | PCE (%) Without NPs | PCE (%) with NPs | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITO/PEDOT:PSS/P3HT:PCBM:NPs/LiF/Al | Ag/Mg | P3HT/PCBM | 2.29 | 4.11 | [18] |

| ITO/PEDOT:PSS:CuS/P3HT:PC61BM:NPs/LiF/Al | CuS | PEDOT:PSS | 2.01 | 4.51 | [19] |

| ITO/PEDOT:PSS/P3HT:PCBMNP/LiF/Al | ZnS | P3HT:PCBM | 1.90 | 4.00 | [20] |

| ITO/ZnO/PTB7:PCBM/MoO3/Al | Ag | ZnO | 6.53 | 7.25 | [21] |

| ITO/PEDOT:PSS/PTB7:PC71BM/Ca/Al | Au@Ag@SiO2 | PTB7:PC71BM | 7.72 | 9.56 | [22] |

| ITO/ZnS/Y2O3/PTB7:PC71BM/MoO3/Ag | ZnO/Y2O3 | ZnO | 5.77 | 6.22 | [23] |

| ITO/PEDOT:PSS:Au/PTB7:PC71BM/Ca | Au | PEDOT:PSS | 7.50 | 8.10 | [24] |

| ITO/PEDOT:PSS/PTB7:PC71BM/Ca/Al | Au@Ag@SiO2 | PEDOT:PSS | 7.72 | 9.04 | [22] |

| ZnS/Co (%wt) | (eV) | (eV) | (V) | (mAcm−2) | FF (%) | PCE (%) | Rs (Ωcm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0%wt | 1.62 | 1.08 | 0.54 | 10.23 | 44.40 | 2.35 | 850 |

| 1%wt | 1.54 | 0.98 | 0.56 | 14.85 | 49.78 | 3.91 | 443 |

| 3%wt | 1.50 | 0.94 | 0.56 | 15.71 | 57.41 | 4.76 | 359 |

| 5%wt | 1.57 | 1.01 | 0.56 | 13.36 | 47.52 | 3.55 | 571 |

| ZnS/Co (%wt) | () | γ () |

|---|---|---|

| 0%wt (Pristine) | ||

| 1%wt | ||

| 3%wt | ||

| 5%wt |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ike, J.N.; Taziwa, R.T. Optimizing Organic Photovoltaic Efficiency Through Controlled Doping of ZnS/Co Nanoparticles. Solids 2025, 6, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/solids6040069

Ike JN, Taziwa RT. Optimizing Organic Photovoltaic Efficiency Through Controlled Doping of ZnS/Co Nanoparticles. Solids. 2025; 6(4):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/solids6040069

Chicago/Turabian StyleIke, Jude N., and Raymond Tichaona Taziwa. 2025. "Optimizing Organic Photovoltaic Efficiency Through Controlled Doping of ZnS/Co Nanoparticles" Solids 6, no. 4: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/solids6040069

APA StyleIke, J. N., & Taziwa, R. T. (2025). Optimizing Organic Photovoltaic Efficiency Through Controlled Doping of ZnS/Co Nanoparticles. Solids, 6(4), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/solids6040069