Effects of Preparation Conditions and Ammonia/Methylamine Treatment on Structure of Graphite Intercalation Compounds with FeCl3, CoCl2, NiCl2 and Derived Metal-Containing Expanded Graphite

Abstract

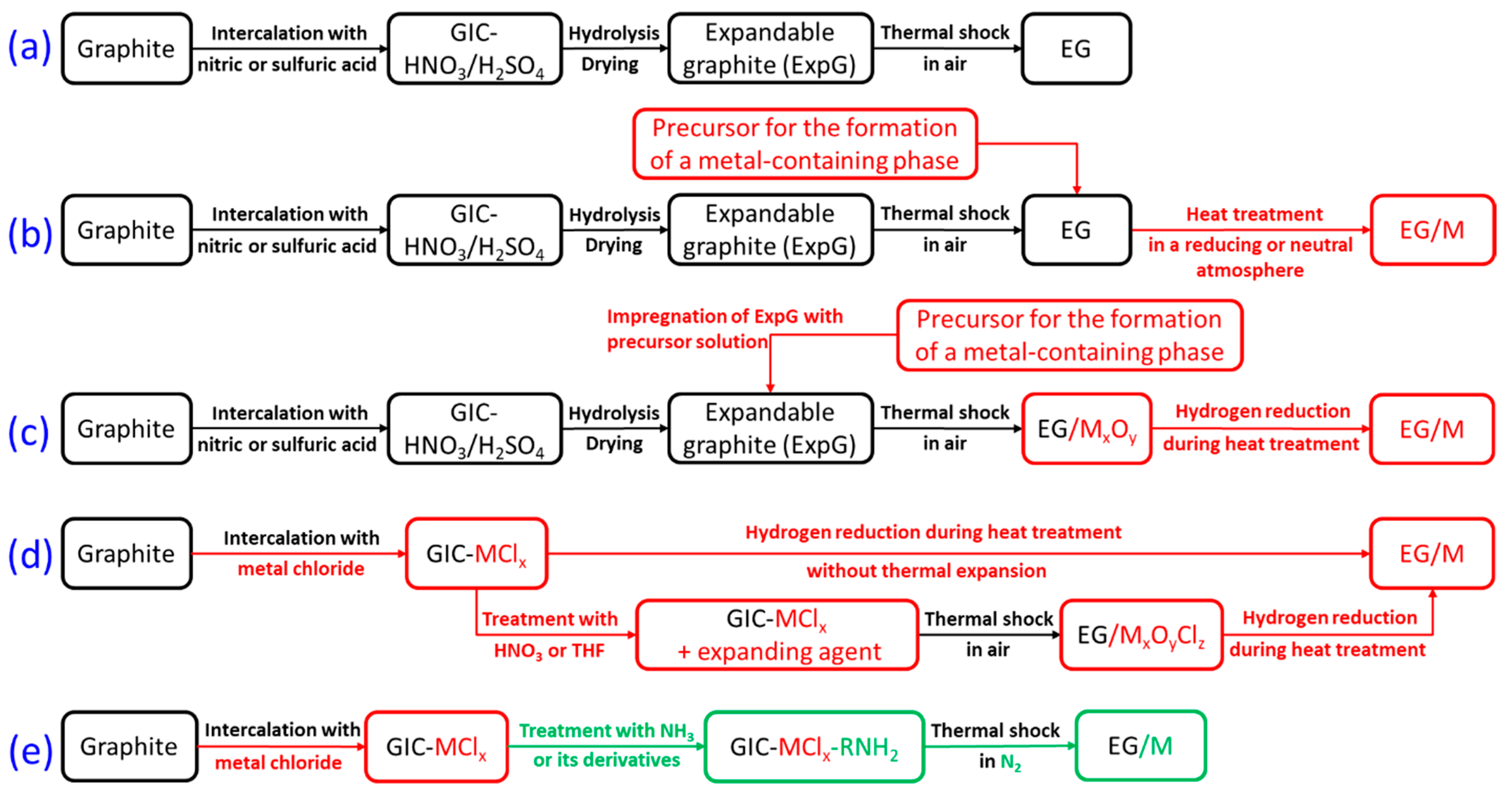

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.2. Investigation Techniques

3. Results

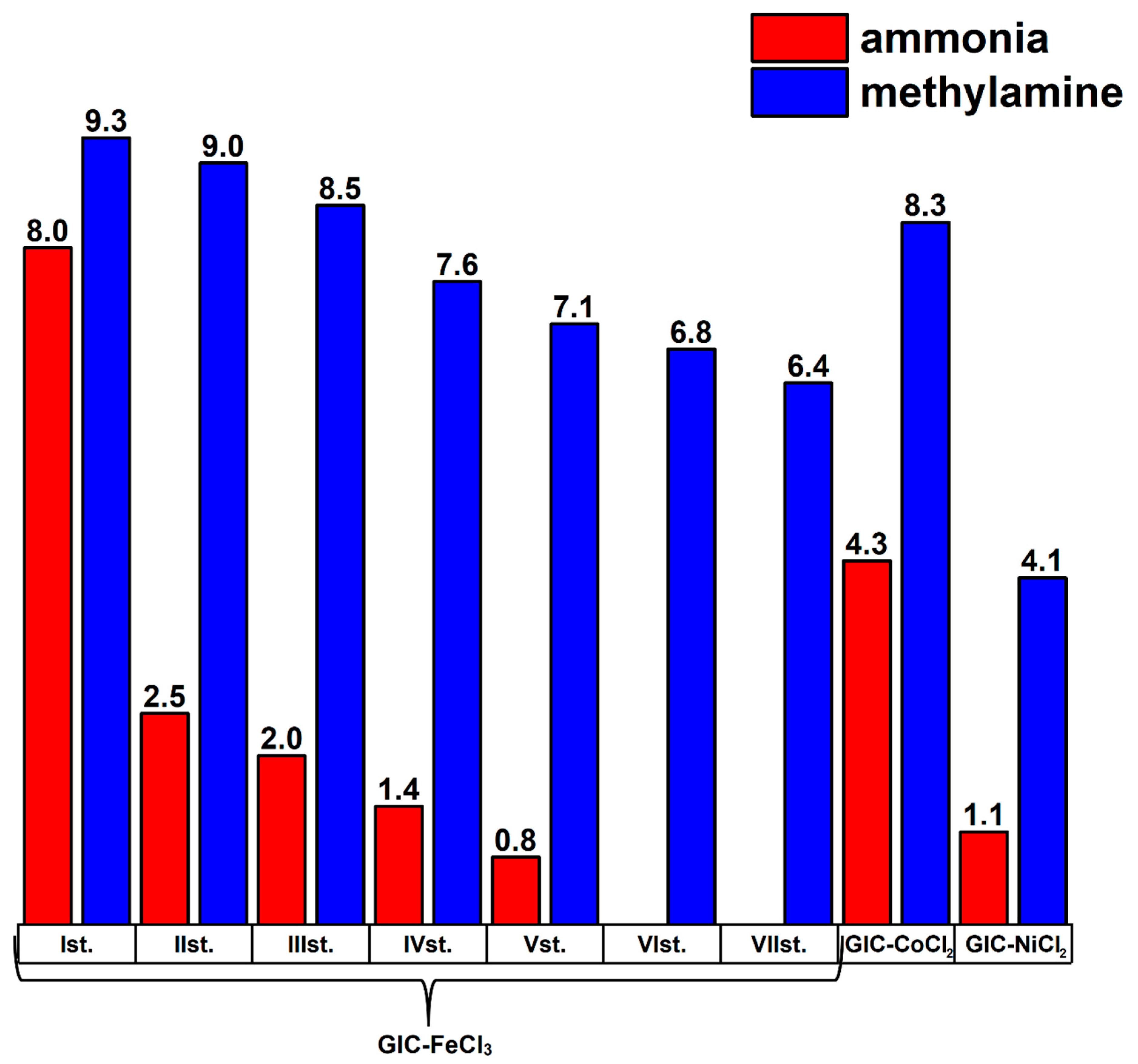

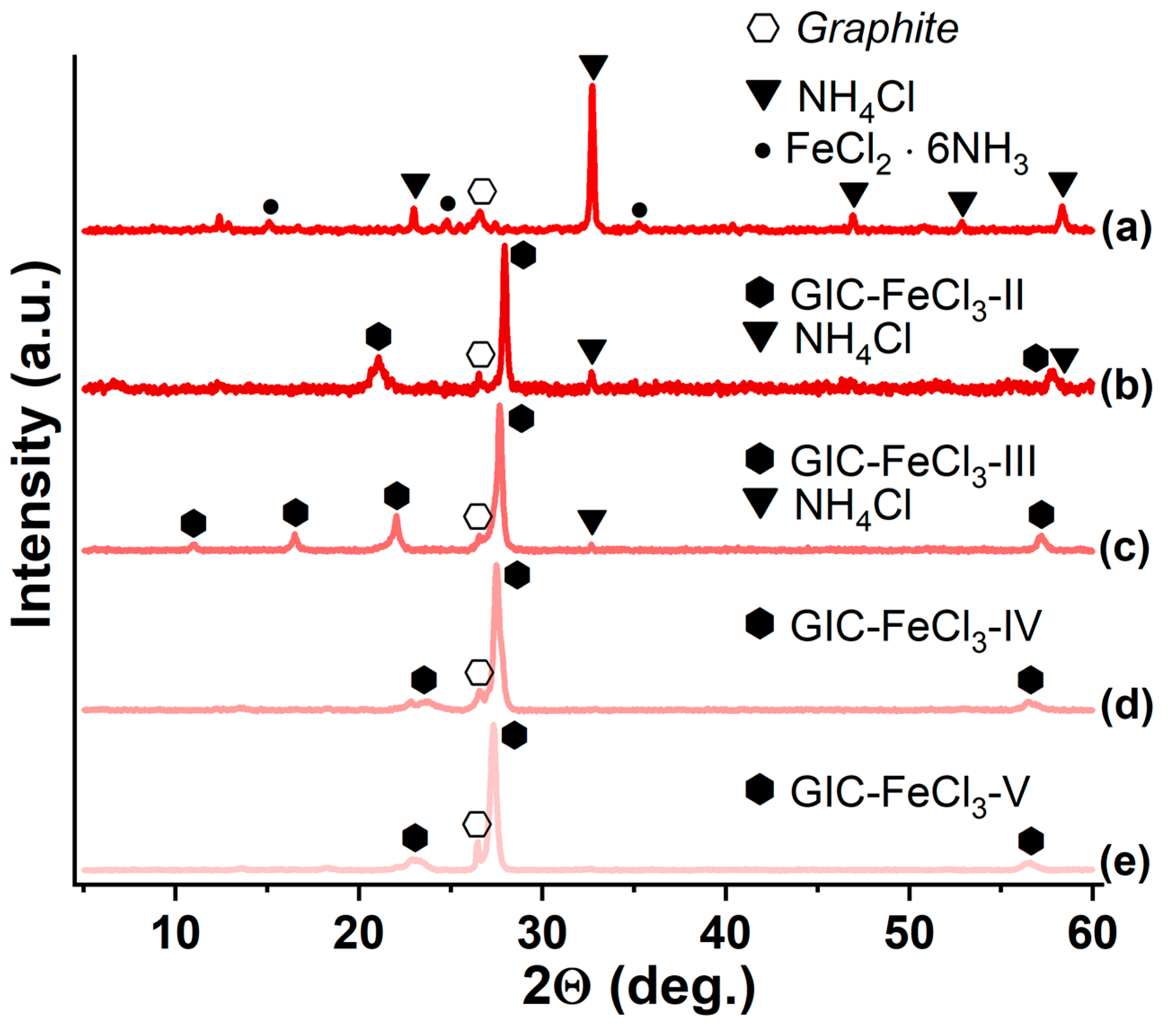

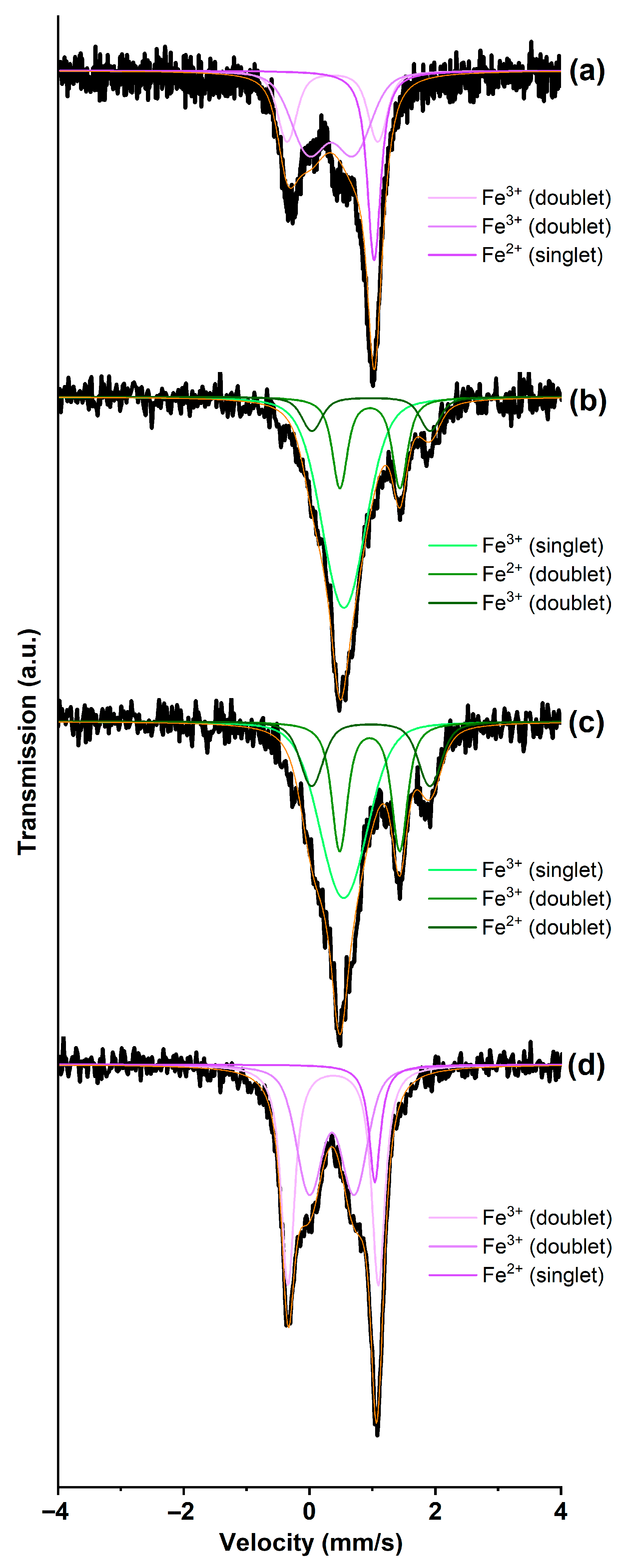

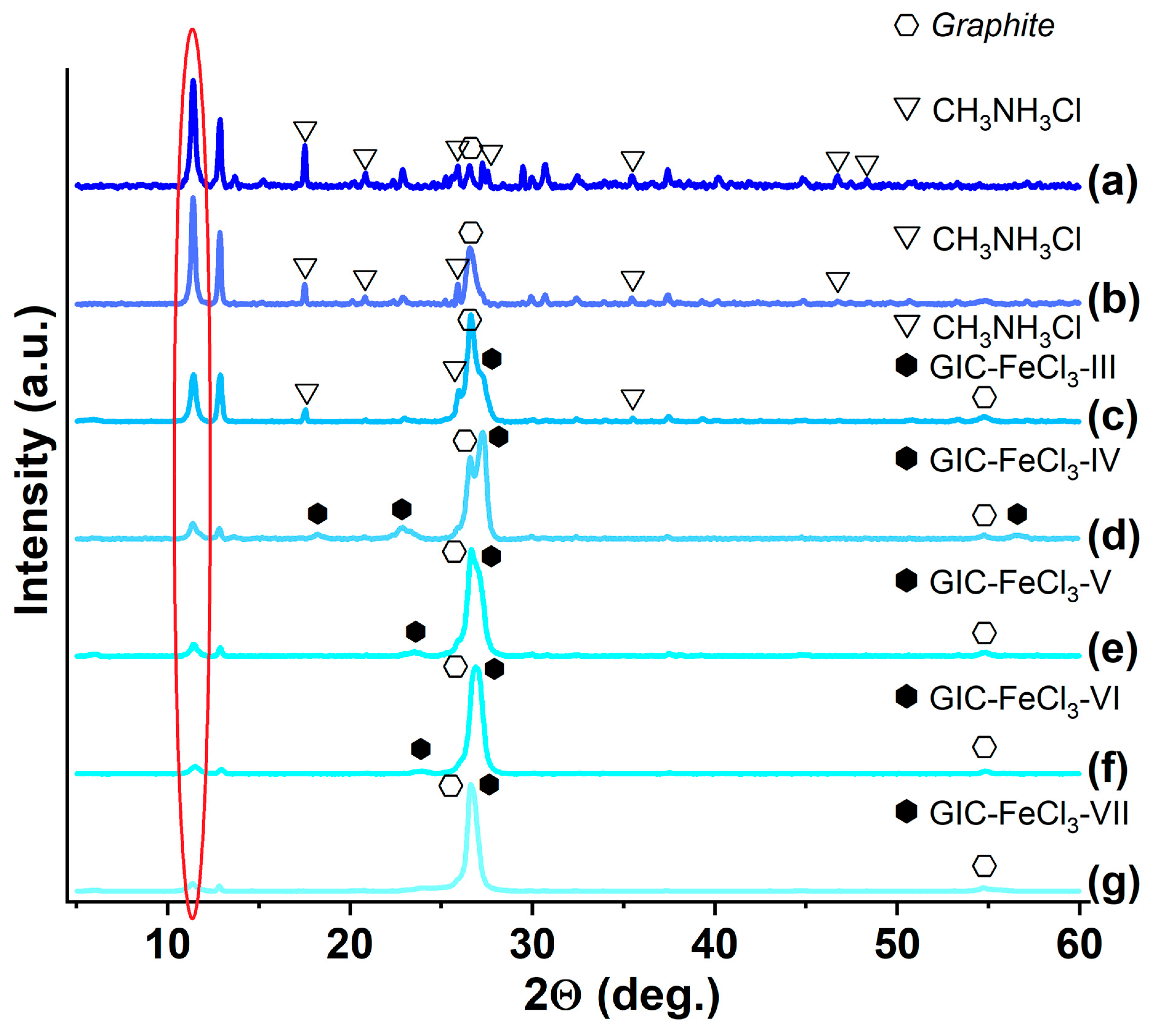

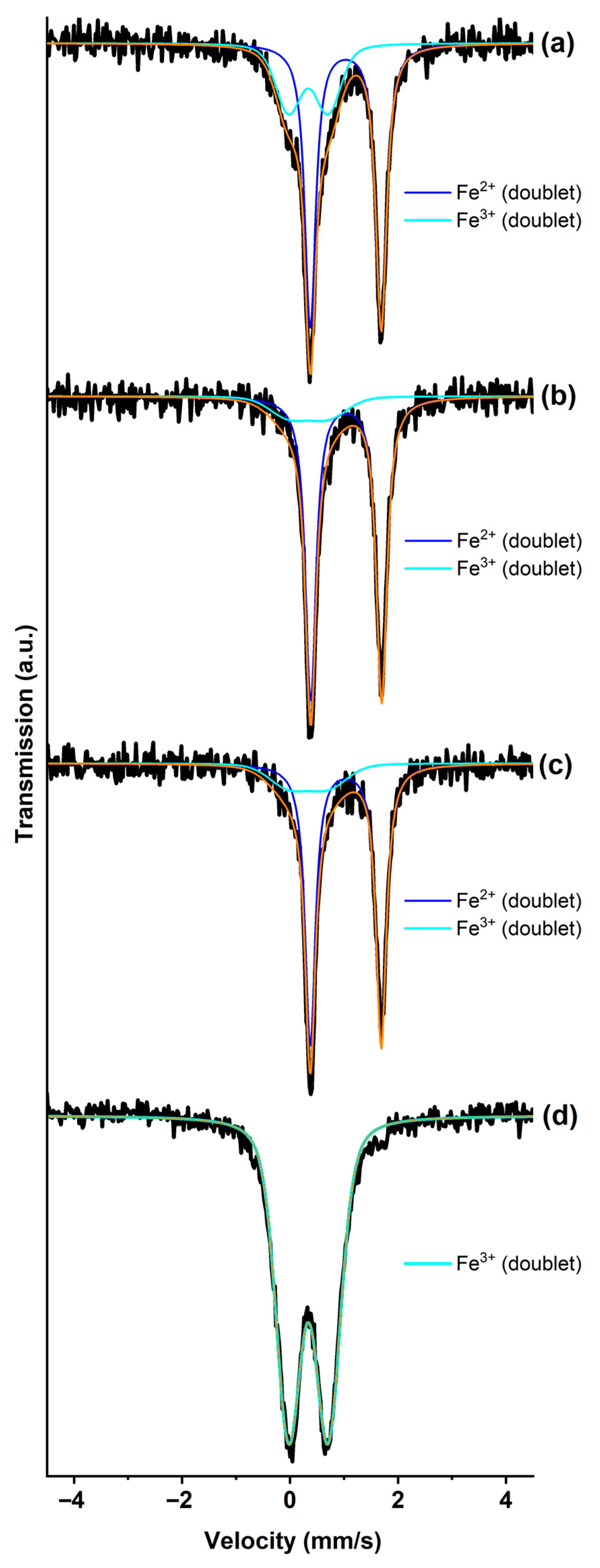

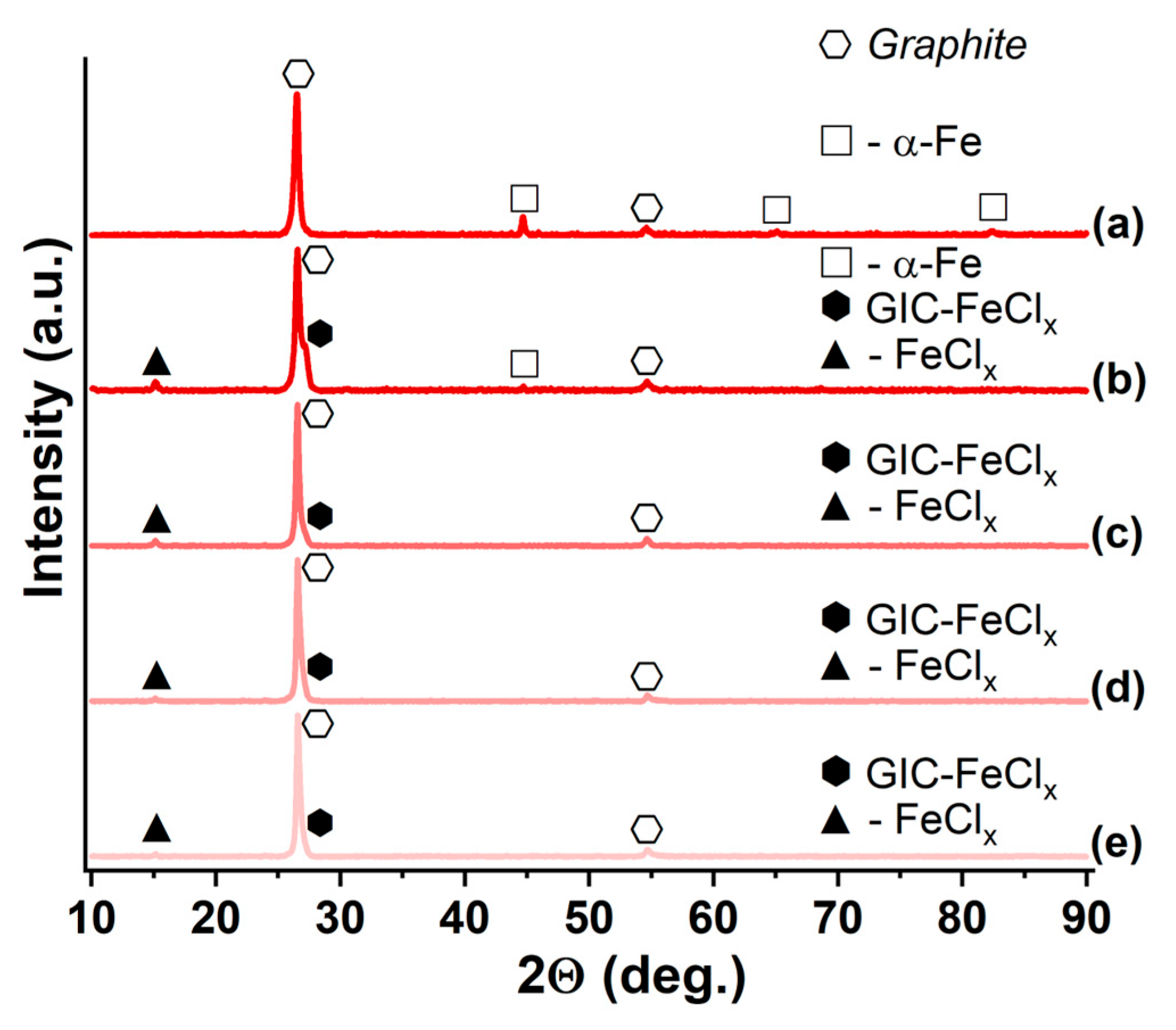

3.1. GIC-FeCl3, Saturated with Ammonia and Methylamine

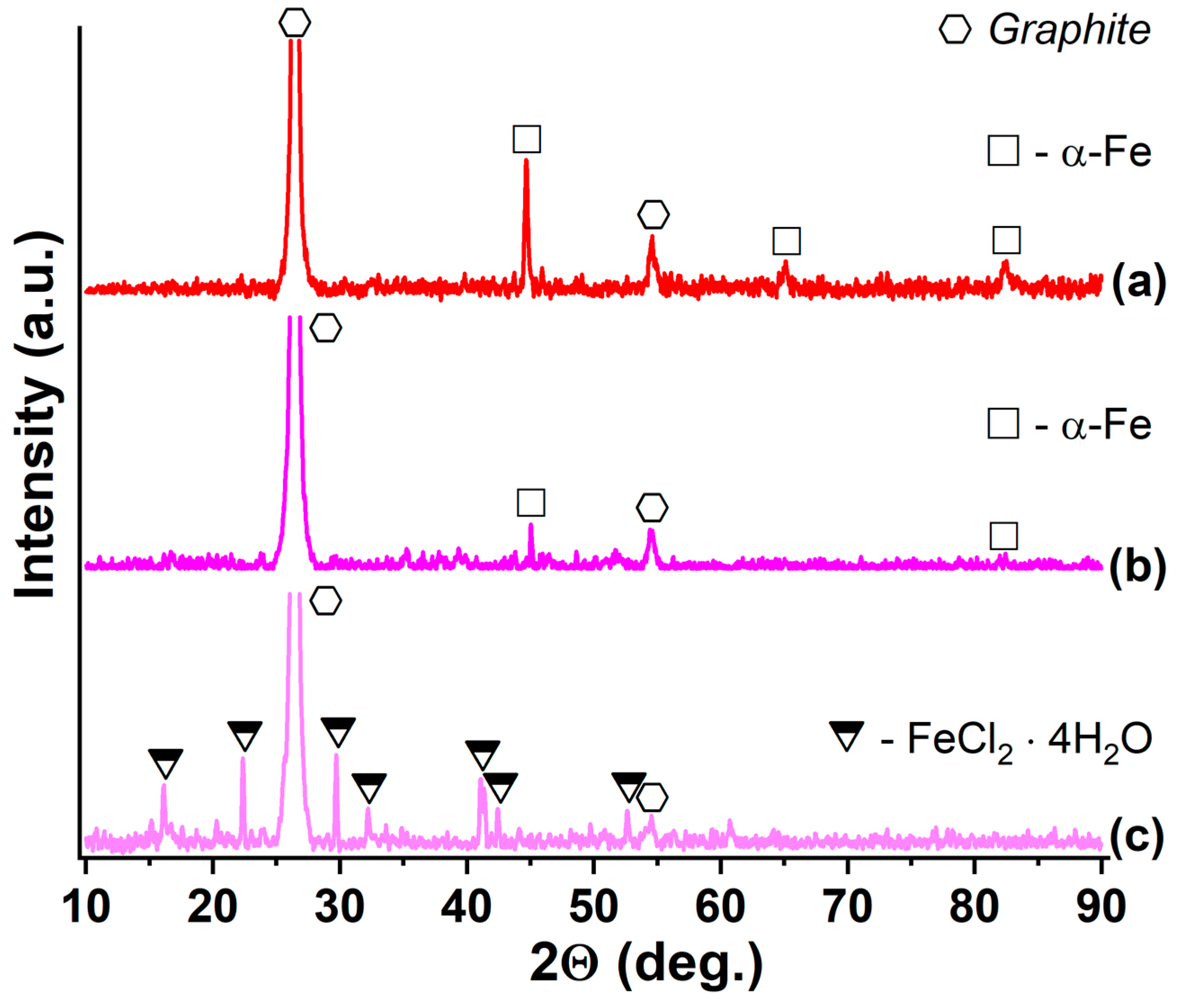

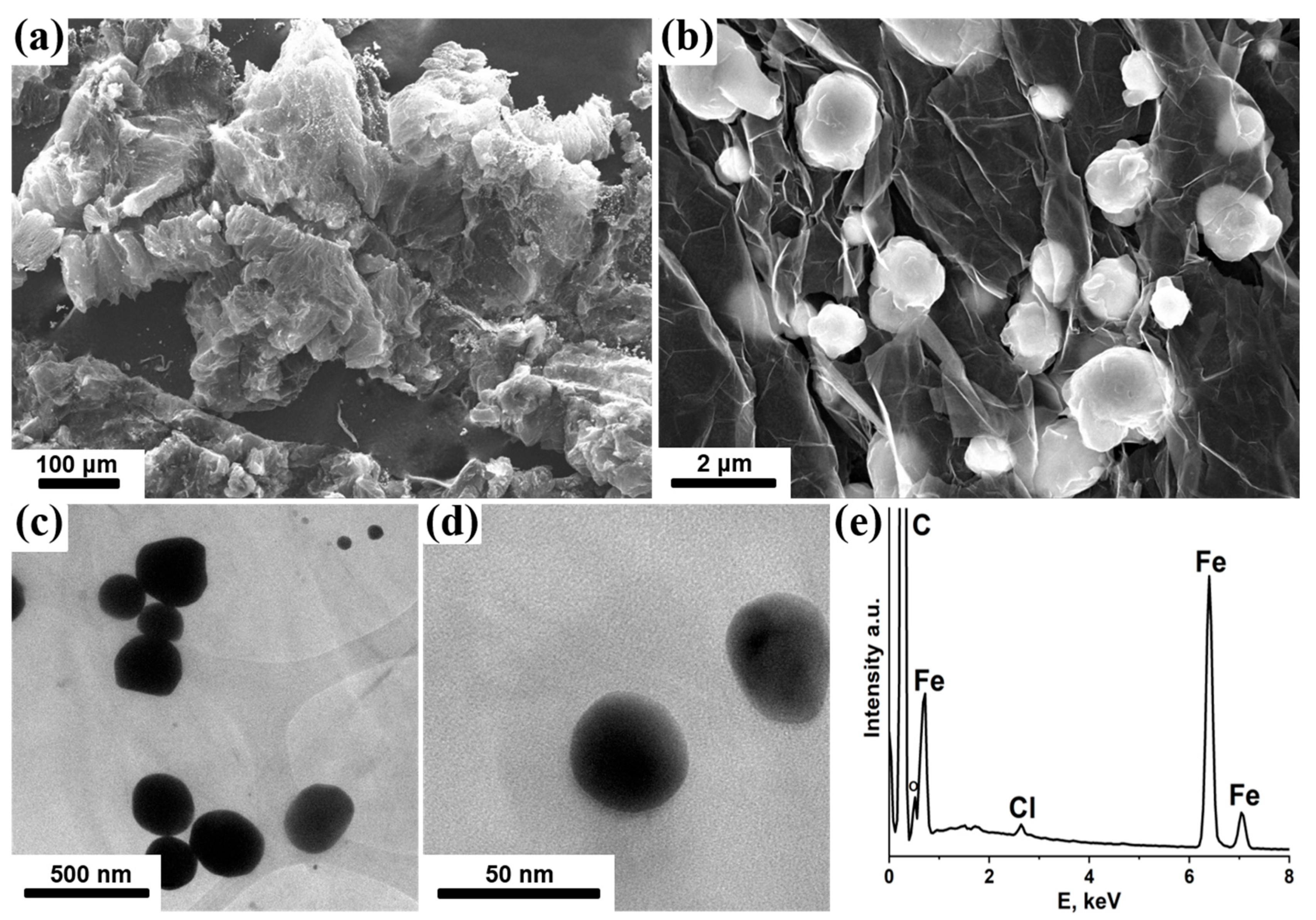

3.2. Thermal Expansion of GIC-FeCl3-RNH2

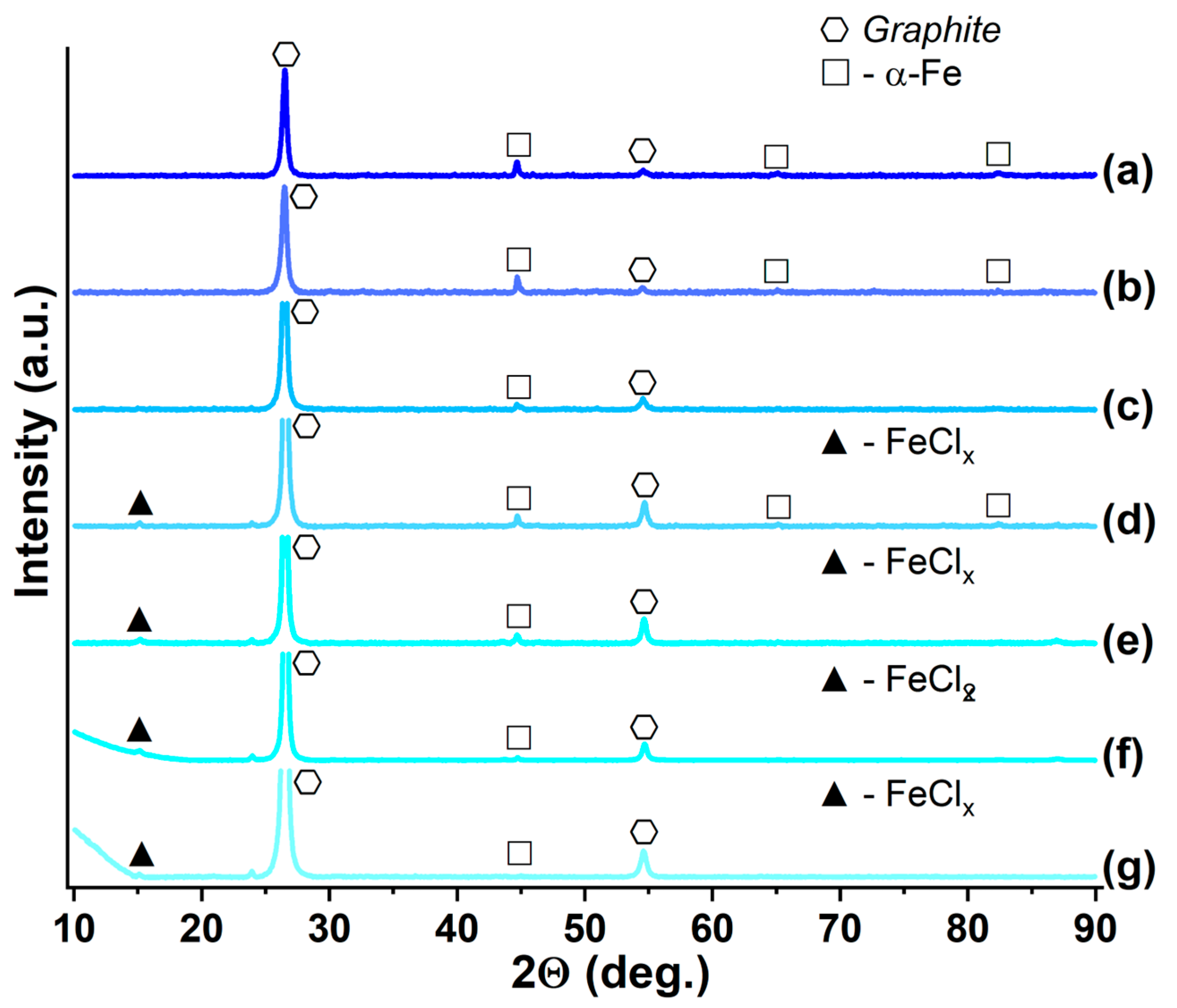

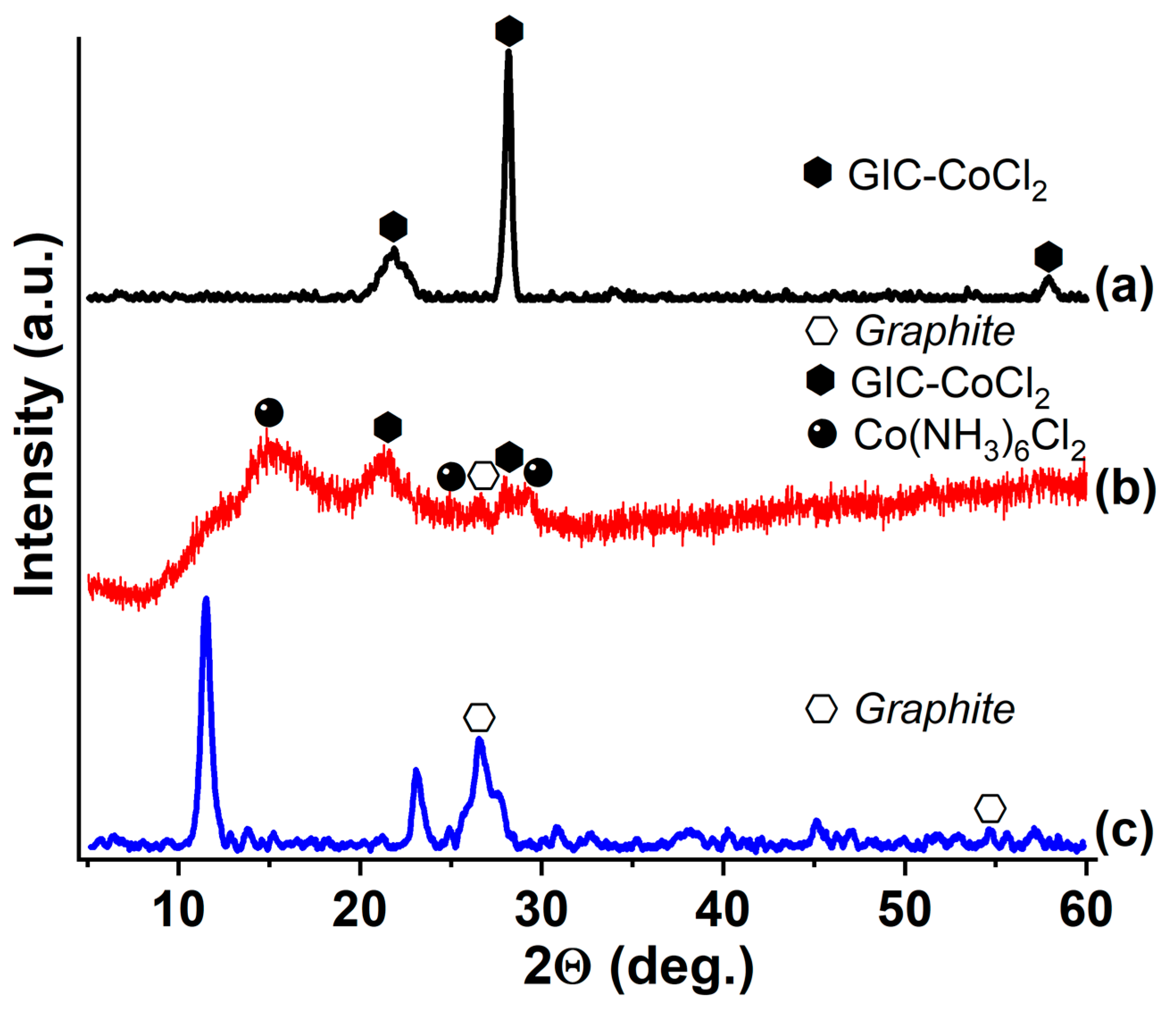

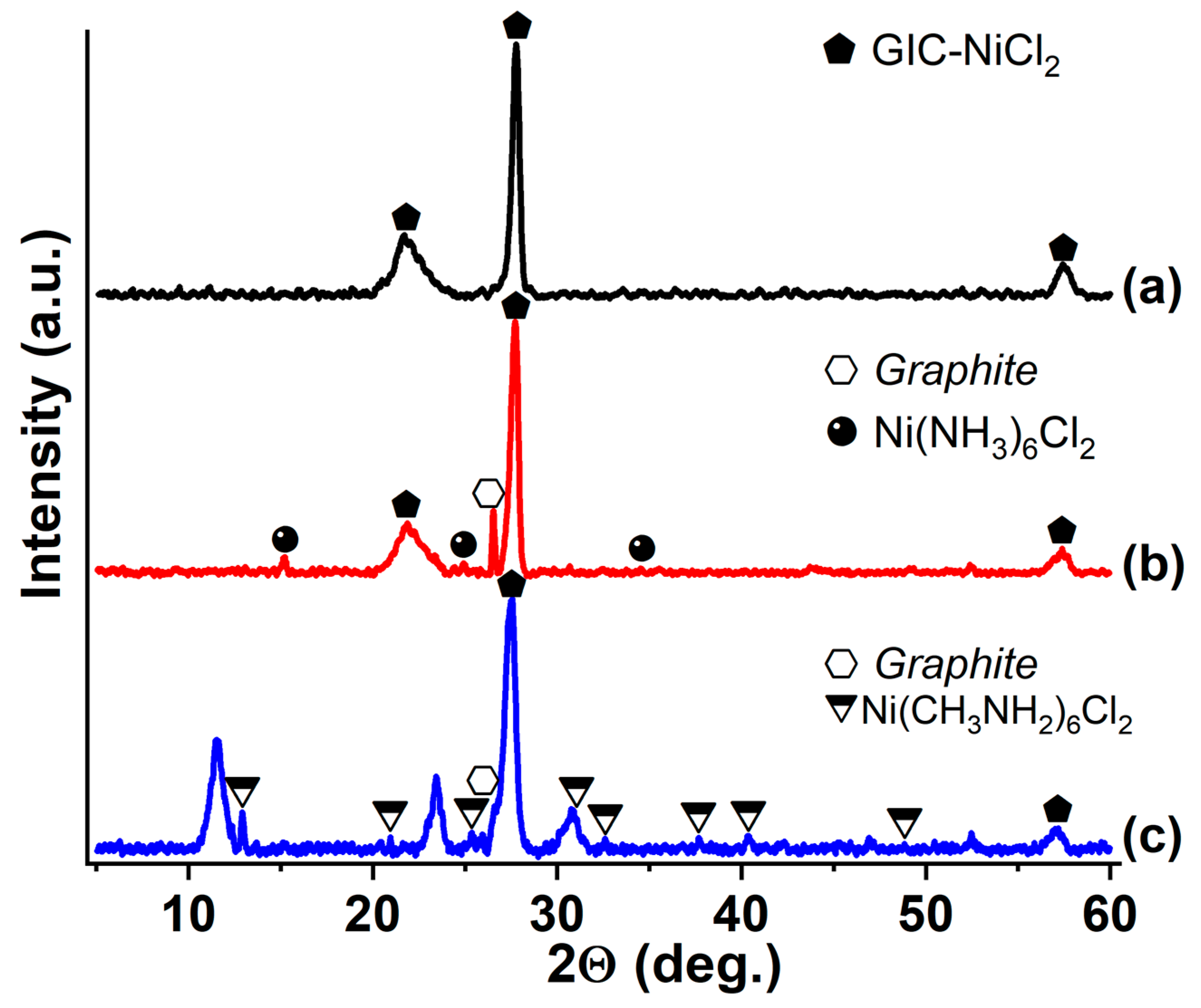

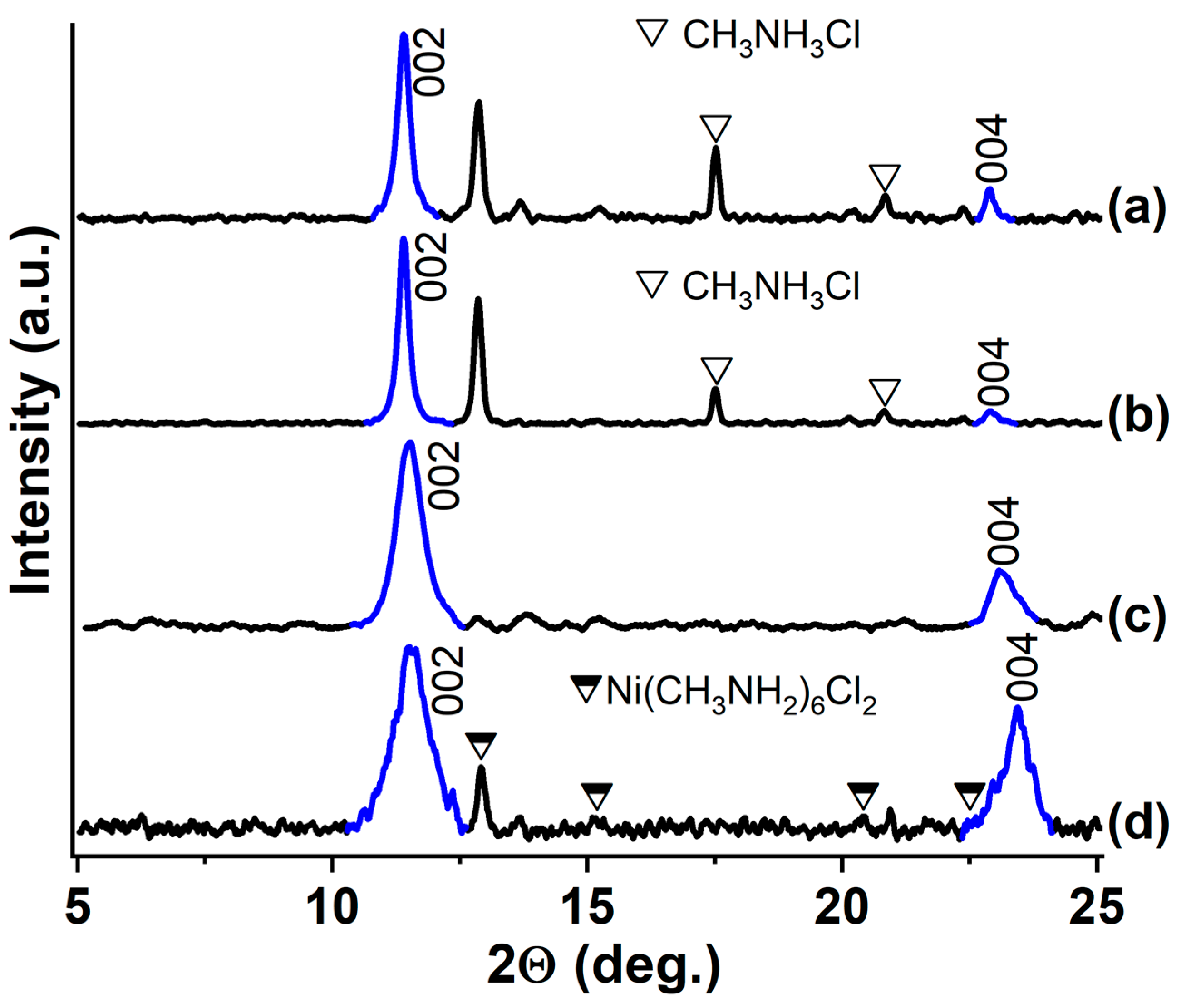

3.3. GIC-CoCl2 and GIC-NiCl2, Saturated with Ammonia and Methylamine

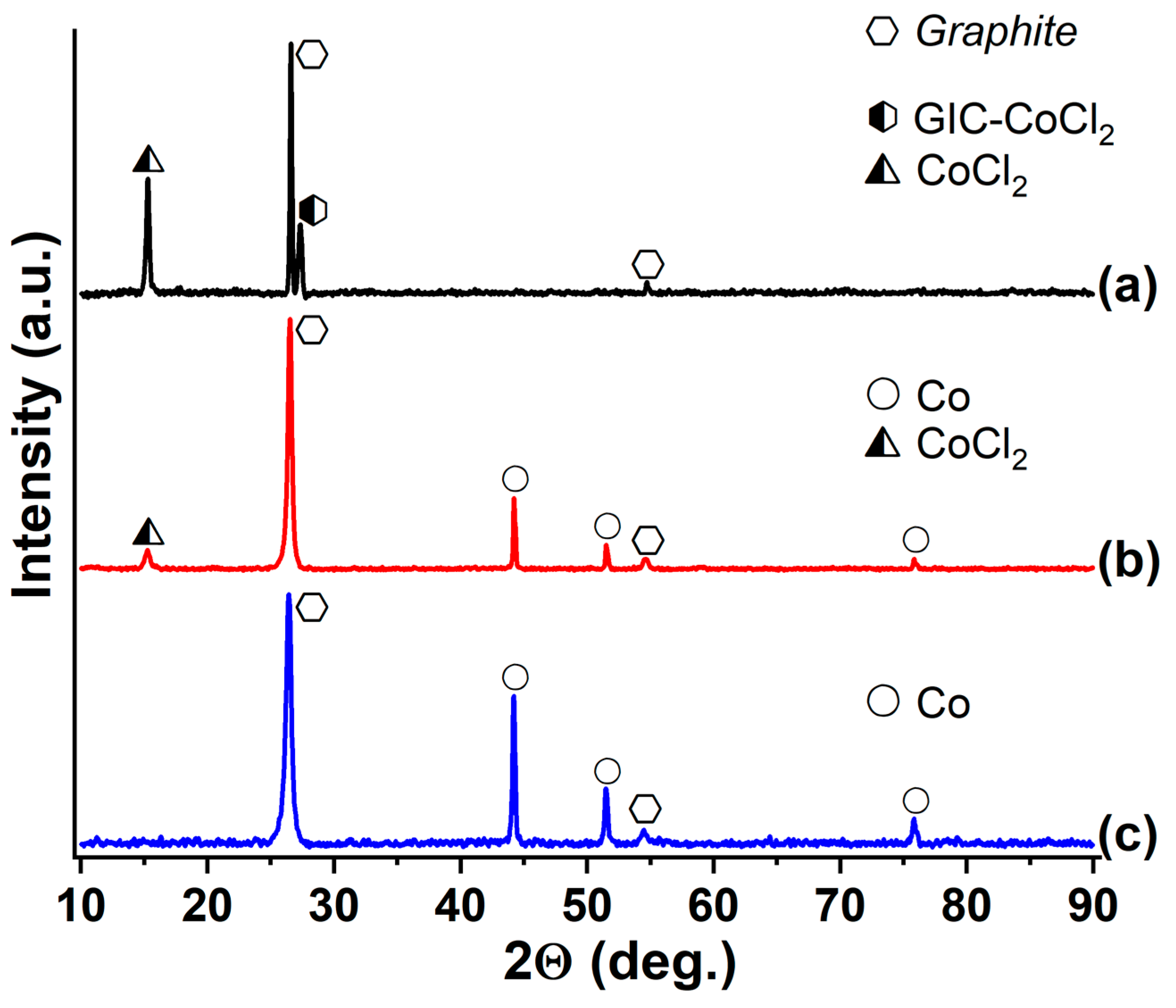

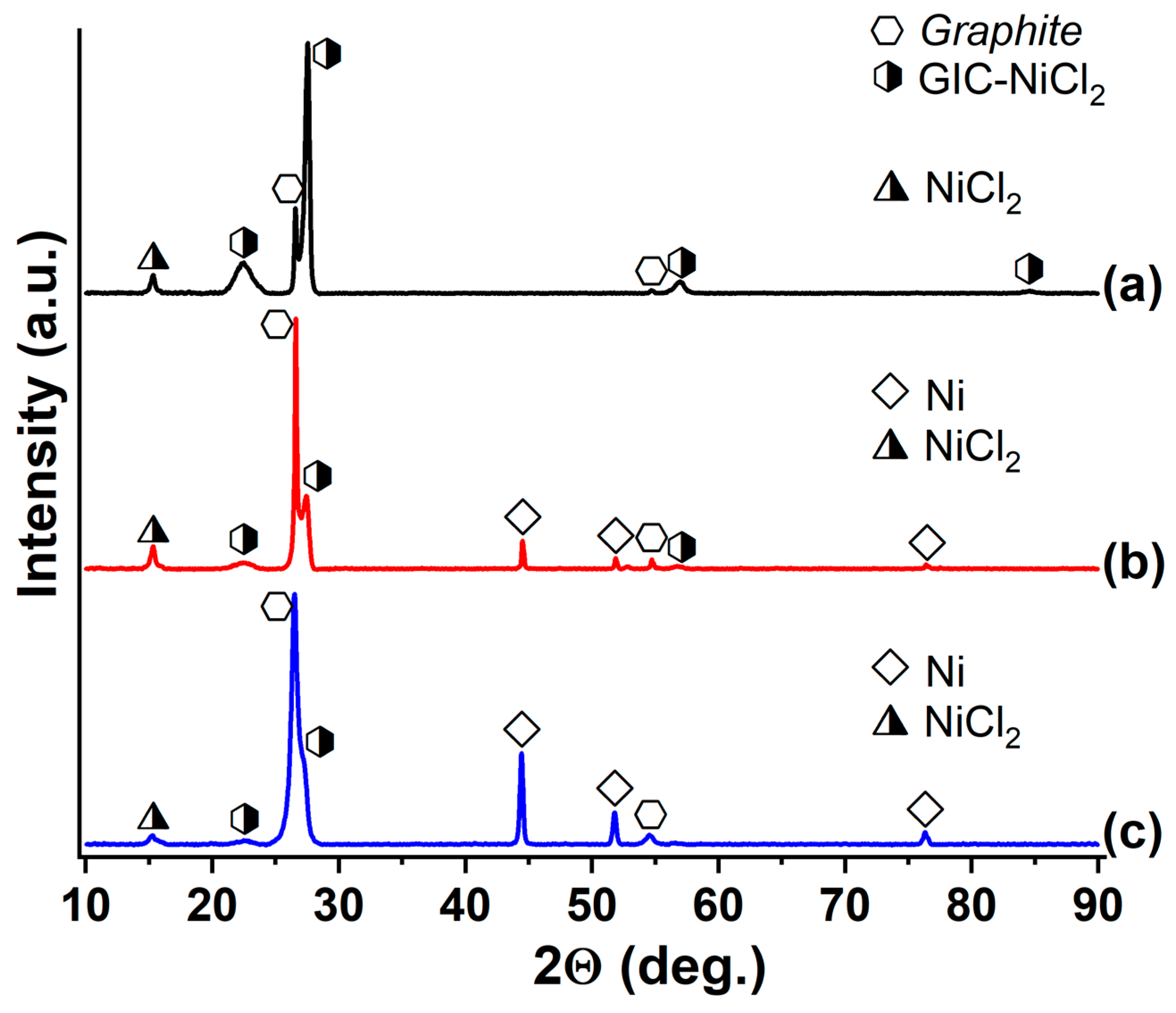

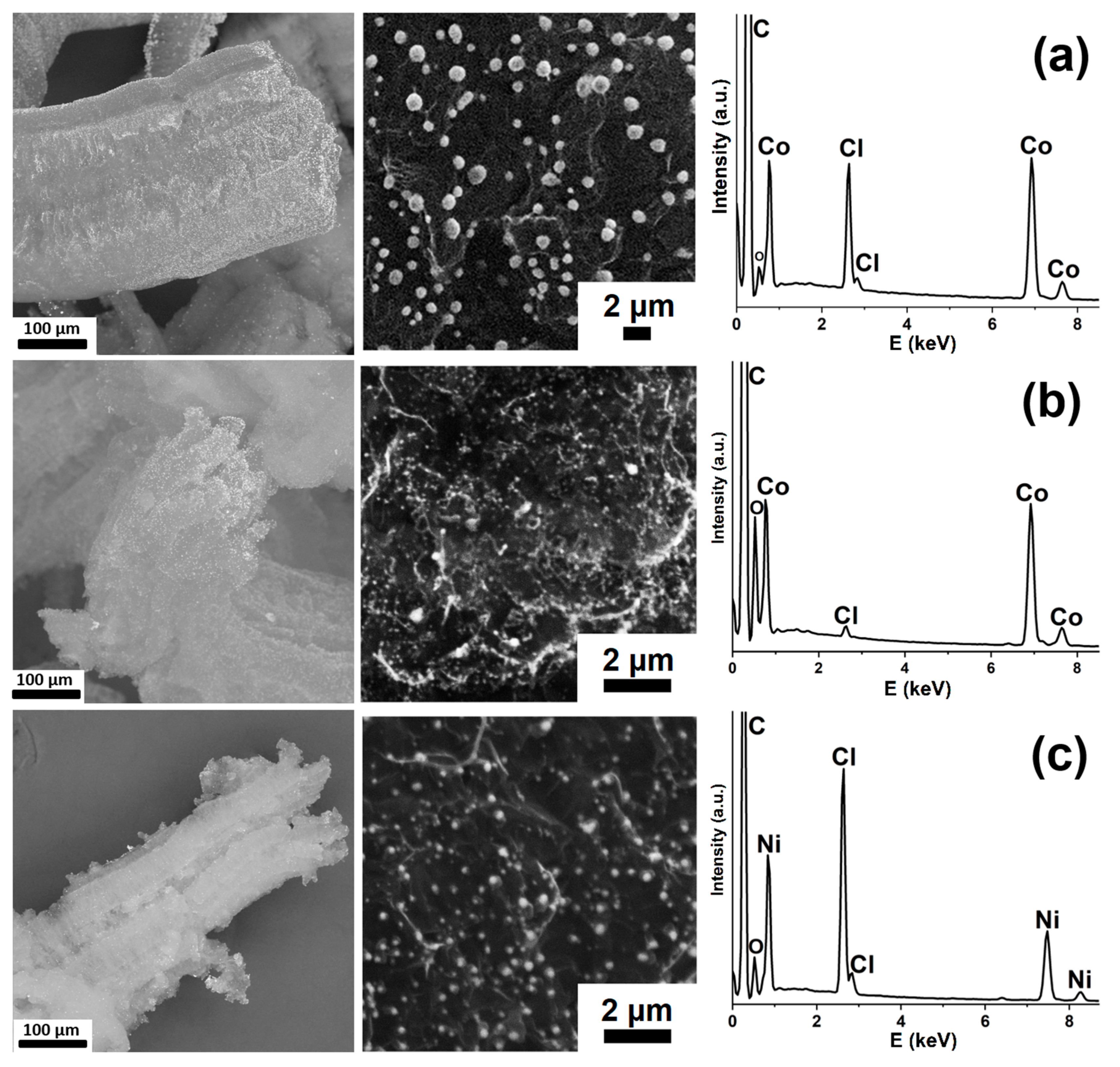

3.4. Thermal Expansion of GIC-MCl2-RNH2

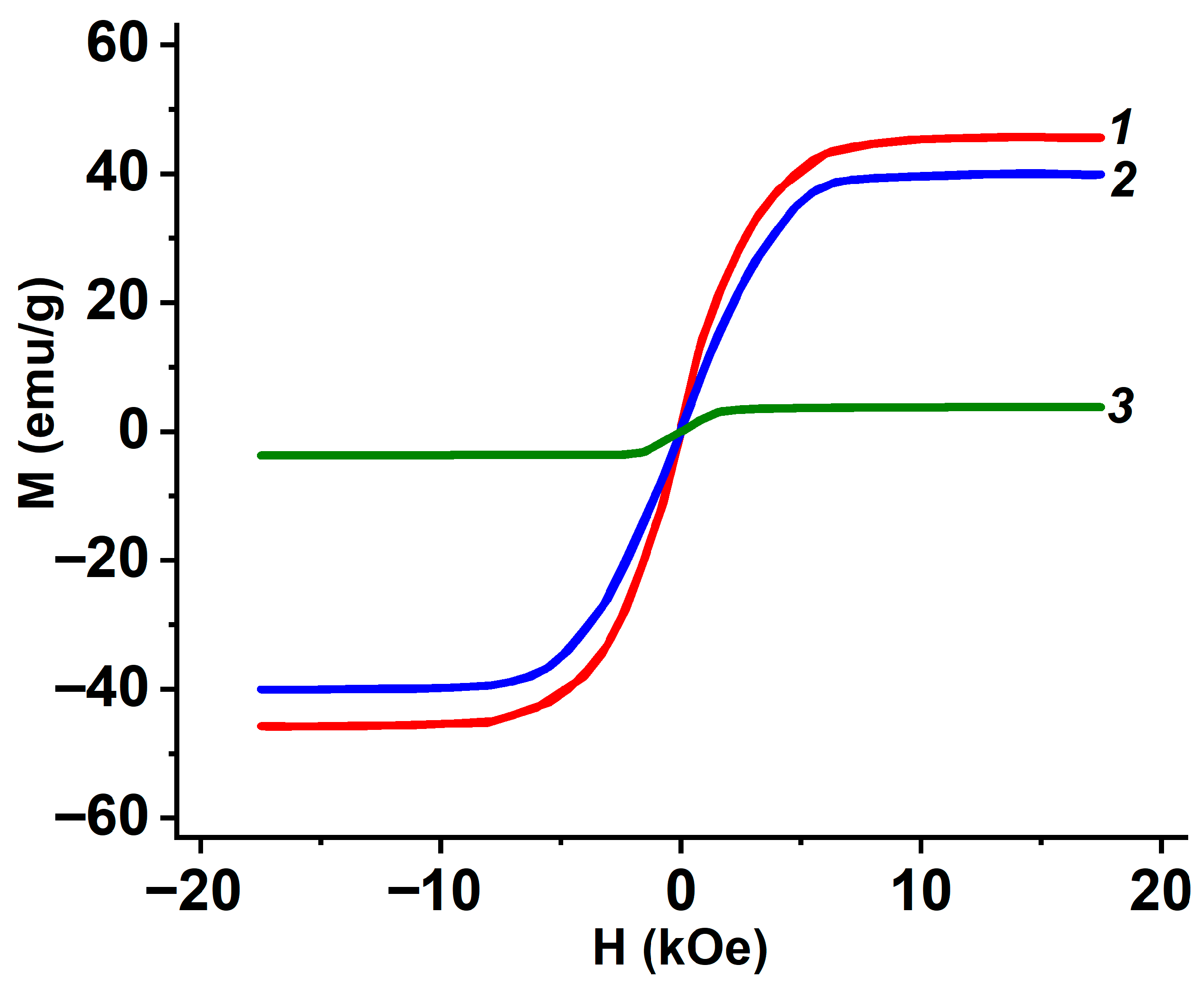

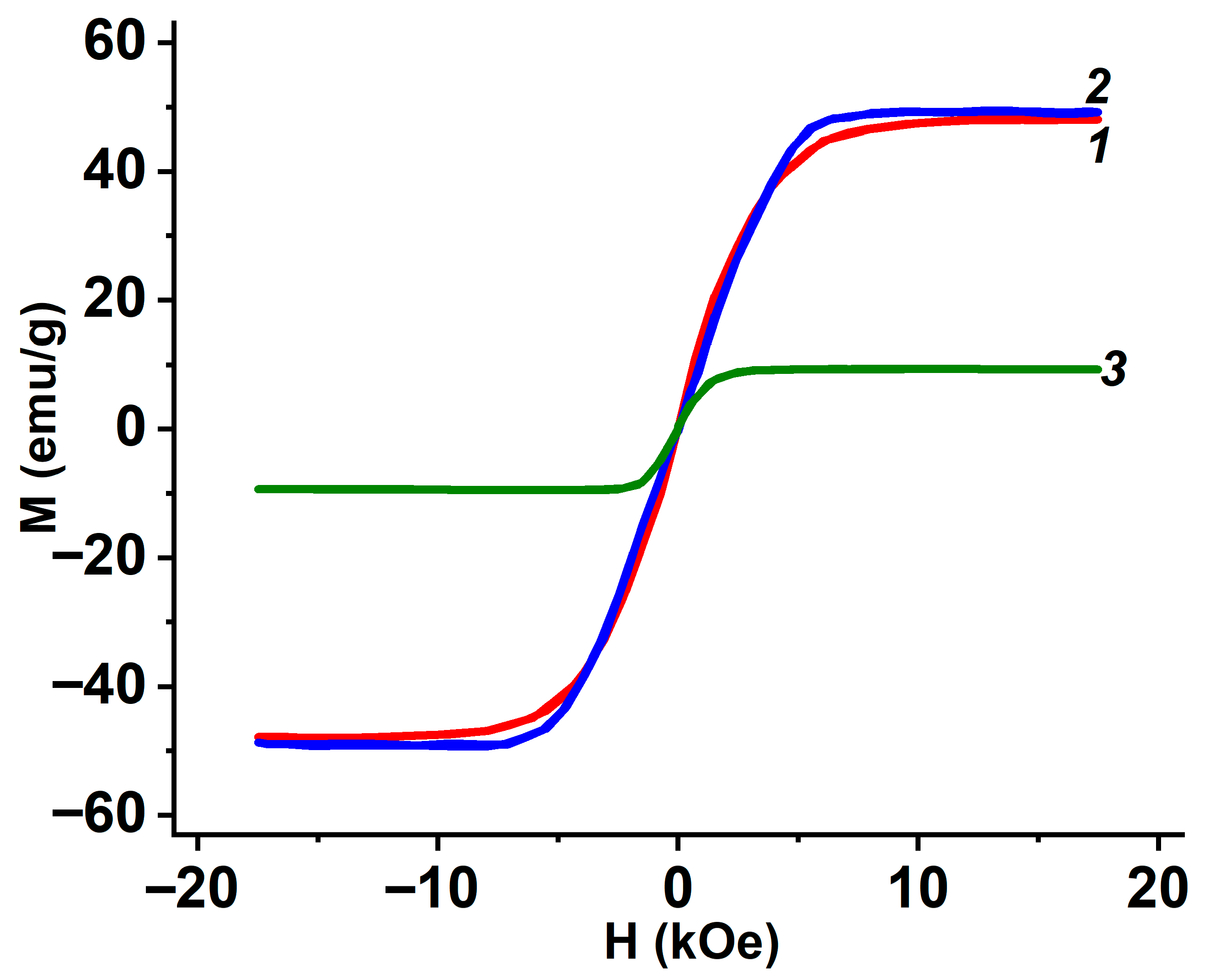

3.5. Magnetic Properties of Metal-Containing Composites EG

4. Conclusions

- Interaction of chloride with NH3/CH3NH2, leading to the formation of the M(RNH2)6Cl2 complex, as evidenced by the appearance of phases corresponding to these compounds in the diffraction patterns of GIC saturated with ammonia and methylamine;

- Partial deintercalation of the introduced chloride. This is evidenced by the appearance of reflexes corresponding to the graphite phase;

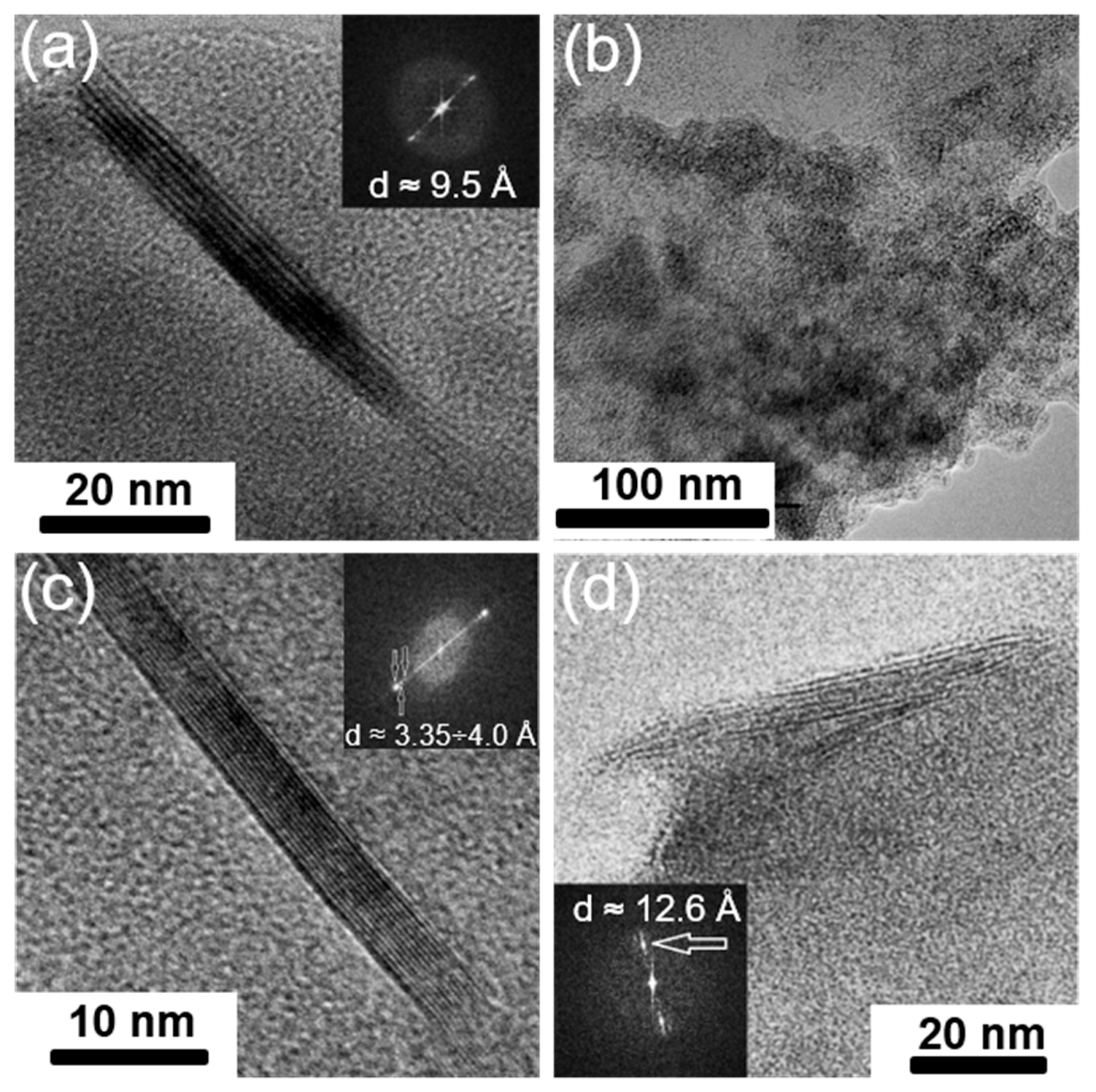

- Formation of a methylamine complex with iron chloride in the interlayer space of graphite. This can be judged by some direct and indirect signs. These include the following: the absence of reflexes in the diffraction patterns of the processed GIC corresponding to the initial GIC at a low intensity of peaks corresponding to graphite (in the case of high saturation), the appearance of reflexes that can be attributed to the GIC-M(RNH2)6Cl2 phase; the presence of various stages of a doublet in the Mossbauer spectrum of methylamine-saturated GIC-FeCl3, which differs greatly in its parameters from the doublet corresponding directly to the methylamine complex of iron chloride; an increase in the interlayer distance up to 15.6 Å, confirmed by TEM; as well as the ability of GIC treated with NH3/CH3NH2 to undergo effective thermal expansion.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GIC | Graphite intercalation compound |

| EG | Expanded graphite |

| ExpG | Expandable graphite |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| EDX | Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

References

- Cai, X.; Qiu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Jiao, X. Nanoscale Zero-Valent Iron Loaded Vermiform Expanded Graphite for the Removal of Cr (VI) from Aqueous Solution. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2021, 8, 210801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, K.; Fujishige, M.; Kitazawa, H.; Akuzawa, N.; Medina, J.O.; Morelos-Gomez, A.; Cruz-Silva, R.; Araki, T.; Hayashi, T.; Terrones, M.; et al. Oil Sorption by Exfoliated Graphite from Dilute Oil–Water Emulsion for Practical Applications in Produced Water Treatments. J. Water Process Eng. 2015, 8, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Shen, J.; Tang, T.; Huang, R. Dispersion of Iron Nano-Particles on Expanded Graphite for the Shielding of Electromagnetic Radiation. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2010, 322, 3084–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, D.; Wu, Z.; Xu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Shi, J.; Tang, J.; Yan, P. Study on the Microwave Absorbing Properties of Fe Nanoparticles Prepared by the HEIBE Method in Expanded Graphite Matrix Composites. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 860, 158434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zheng, C.; Li, X.; Man, Q.; Liu, X. Expanded Graphite/Co@C Composites with Dual Functions of Corrosion Resistance and Microwave Absorption. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 23, 3557–3569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M.; Fischer, N.; Claeys, M. Preparation of Isolated Co3O4 and Fcc-Co Crystallites in the Nanometre Range Employing Exfoliated Graphite as Novel Support Material. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 2910–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vovchenko, L.; Matzui, L.; Oliynyk, V.; Launetz, V.; Prylutskyy, Y.; Hui, D.; Strzhemechny, Y.M. Modified exfoliated graphite as a material for shielding against electromagnetic radiation. Int. J. Nanosci. 2008, 7, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afanasov, I.M.; Lebedev, O.I.; Kolozhvary, B.A.; Smirnov, A.V.; Van Tendeloo, G. Nickel/Carbon Composite Materials Based on Expanded Graphite. New Carbon Mater. 2011, 26, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Jin, S.; Sun, J.; Li, L.; Zou, H.; Wen, P.; Lv, G.; Lv, X.; Shu, Q. Sandwich-like Sulfur-Free Expanded Graphite/CoNi Hybrids and Their Synergistic Enhancement of Microwave Absorption. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 862, 158005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, P.; Rozmanowski, T.; Frankowski, M. Methanol Electrooxidation at Electrodes Made of Exfoliated Graphite/Nickel/Palladium Composite. Catal. Lett. 2019, 149, 2307–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Lei, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wu, F.; Song, J.; Yang, Z.; Tan, G.; Man, Q.; Liu, X. Synthesis and Microwave Absorption Properties of Sandwich Microstructure Ce2Fe17N3-δ/Expanded Graphite Composites. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 907, 164445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.V.; Volkova, S.I.; Maksimova, N.V.; Pokholok, K.V.; Kravtsov, A.V.; Belik, A.A.; Posokhova, S.M.; Kalachev, I.L.; Avdeev, V.V. Exfoliated Graphite with γ-Fe2O3 for the Removal of Oil and Organic Pollutants from the Water Surface: Synthesis, Mossbauer Study, Sorption and Magnetic Properties. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 960, 170619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-I.; Hong, Y.; Jang, Y.; Ha, M.-G.; An, H.-R.; Son, B.; Choi, Y.; Kim, H.; Jeong, Y.; Lee, H.U. Efficient Iron Oxide/Expanded Graphite Nanocomposites Prepared by Underwater Plasma Discharge for Removing Heavy Metals. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 14, 1884–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Ma, H.; Xing, B. Preparation of Surfactant Modified Magnetic Expanded Graphite Composites and Its Adsorption Properties for Ionic Dyes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 537, 147995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan Nguyen, H.D.; Nguyen, H.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Le Thi, A.K.; Nguyen, T.D.; Phuong Bui, Q.T.; Bach, L.G. The Preparation and Characterization of MnFe2O4-Decorated Expanded Graphite for Removal of Heavy Oils from Water. Materials 2019, 12, 1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, N.T.H.; Thinh, P.V.; Uyen, D.T.T.; Tien, N.A.; Thanh, N.T.; Sy, D.T. Synthesis and Characterization of Magnetic Expanded Graphite Material (EG@CoFe2O4) Through Sol-Gel Processing. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 991, 012109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinh, N.H.; Hieu, N.P.; Van Thinh, P.; Diep, N.T.M.; Thuan, V.N.; Trinh, N.D.; Thuy, N.H.; Long Giang, B.; Quynh, B.T.P. Magnetic NiFe2O4/Exfoliated Graphite as an Efficient Sorbent for Oils and Organic Pollutants. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2018, 18, 6859–6866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saraf, S.D.; Panda, D.; Gangawane, K.M. Performance Analysis of Hybrid Expanded Graphite-NiFe2O4 Nanoparticles-Enhanced Eutectic PCM for Thermal Energy Storage. J. Energy Storage 2023, 73, 109188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, V.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Bui, T.P.Q.; Nguyen, M.T.; Nguyenh, T.D.; Bach, L.G. Simple Synthesis and Characterization of Cobalt Ferrites on Expanded Graphite by the Direct Sol-Gel Chemistry for Removal of Oil Leakage (Fuel Oil, Diesel Oil and Crude Oil). IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 479, 012054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Wang, R.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, S.; Shen, F.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, H.; Wang, L. A New Magnetic Expanded Graphite for Removal of Oil Leakage. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 81, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, L.; Han, J.; Wu, W.; Tong, G. Effective Modulation of Electromagnetic Characteristics by Composition and Size in Expanded Graphite/Fe3O4 Nanoring Composites with High Snoek’s Limit. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 728, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Shen, J.; Tang, T.; Huang, R. Dispersion of Magnetic Metals on Expanded Graphite for the Shielding of Electromagnetic Radiations. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 90, 133117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, D.D.L. A Perspective on Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Materials Comprising Exfoliated Graphite. Carbon 2024, 216, 118569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Feng, X.; Liu, J.; Guo, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Gao, L.; Tao, Z.; Hao, B.; Yan, X. Expanded Graphite/Nanosilver Composites for Effective Thermal Management and Electromagnetic Interference Shielding of Electronic Devices. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1022, 179794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokina, N.E.; Nikol’skaya, I.V.; Ionov, S.G.; Avdeev, V.V. Acceptor-Type Graphite Intercalation Compounds and New Carbon Materials Based on Them. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2005, 54, 1749–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Jiang, J.; Wu, D.; He, Q.; Wang, Y. Three-Dimensional Conductive Network Constructed by in-Situ Preparation of Sea Urchin-like NiFe2O4 in Expanded Graphite for Efficient Microwave Absorption. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 650, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, M.A.; Morchenko, A.T.; Abosheiasha, H.F.; Kostishyn, V.G.; Turchenko, V.A.; Almessiere, M.A.; Slimani, Y.; Baykal, A.; Trukhanov, A.V. Impact of the Exfoliated Graphite on Magnetic and Microwave Properties of the Hexaferrite-Based Composites. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 878, 160397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Tan, Y.; Yan, T.; Wu, X.; He, G.; Li, H.; Zhou, J.; Tong, H.; Yu, L.; Zeng, J. CoFe2O4-x/Expanded Graphite Composite with Abundant Oxygen Vacancies as a High-Performance Peroxymonosulfate Activator for Antibiotic Degradation. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 718, 136808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, D.D.L. A Review of Exfoliated Graphite. J. Mater. Sci. 2016, 51, 554–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cermak, M.; Perez, N.; Collins, M.; Bahrami, M. Material Properties and Structure of Natural Graphite Sheet. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutfullin, M.A.; Shornikova, O.N.; Vasiliev, A.V.; Pokholok, K.V.; Osadchaya, V.A.; Saidaminov, M.I.; Sorokina, N.E.; Avdeev, V.V. Petroleum Products and Water Sorption by Expanded Graphite Enhanced with Magnetic Iron Phases. Carbon 2014, 66, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunaev, A.V.; Chikin, A.I.; Pokholok, K.V.; Filimonov, D.S.; Arkhangel’skii, I.V. Conversion of Graphite Intercalation Compounds to Carbon Materials Containing Polymetallic Nanoparticles. Inorg. Mater. 2010, 46, 1084–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunaev, A.V.; Sorokina, N.E.; Maksimova, N.V.; Avdeev, V.V. Electrochemical Behavior of Graphite in Nonaqueous FeCl3 Solutions. Inorg. Mater. 2005, 41, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizutani, Y.; Abe, T.; Asano, M.; Harada, T. Bi-Intercalation of H2SO4 into Stages 4-6 FeCl3-Graphite Intercalation Compounds. J. Mater. Res. 1993, 8, 1586–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilquin, J.-Y.; Fournier, J.; Guay, D.; Dudelet, J.P.; Dénès, G. Intercalation of CoCl2 into Graphite: Mixing Method vs Molten Salt Method. Carbon 1997, 35, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumpp, E.; Werner, F. Graphite Intercalation Compounds with Chlorides of Manganese, Nickel and Zinc. Carbon 1966, 4, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selig, H.; Ebert, L.B. Graphite Intercalation Compounds. In Advances in Inorganic Chemistry and Radiochemistry; Emeléus, H.J., Sharpe, A.G., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1980; Volume 23, pp. 281–327. [Google Scholar]

- Lutfullin, M.A.; Shornikova, O.N.; Sorokina, N.E.; Avdeev, V.V. Interaction of FeCl3-Intercalated Graphite with Intercalants of Different Strengths. Inorg. Mater. 2014, 50, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.-B.; Lin, S.-Y.; Nguyen, T.D.H.; Chung, H.-C.; Tran, N.T.T.; Han, N.T.; Liu, H.-Y.; Pham, H.D.; Lin, M.-F. FeCl3 Graphite Intercalation Compounds: Iron-Ion-Based Battery Cathodes. In First-Principles Calculations for Cathode, Electrolyte and Anode Battery Materials; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Niitani, K.; Morita, M.; Abe, T. Electrochemical Preparation of Exfoliated Graphite Composites from a Ferric Chloride-Graphite Intercalation Compound. Carbon Trends 2025, 21, 100560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Lin, Z.; Ren, H.; Duan, X.; Shakir, I.; Huang, Y.; Duan, X. Layered Intercalation Materials. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2004557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoropanov, A.S.; Kizina, T.A.; Samal, G.I.; Vecher, A.A.; Novikov, Y.N.; Vol’Pin, M.E. Thermal analysis of graphite intercalation compounds. Synth. Met. 1984, 9, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tominaga, T.; Sakai, T.; Kimura, T. A Mössbauer Study of Graphite Intercalated with Iron(III) Chloride and Aluminum Chloride. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1976, 49, 2755–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vol’pin, M.E.; Novikov, Y.N.; Lapkina, N.D.; Kasatochkin, V.I.; Struchkov, Y.T.; Kazakov, M.E.; Stukan, R.A.; Povitskij, V.A.; Karimov, Y.S.; Zvarikina, A.V. Lamellar Compounds of Graphite with Transition Metals. Graphite as a Ligand. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975, 97, 3366–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asch, L.; Adloff, J.P.; Friedt, J.M.; Danon, J. Motional Effects in the Mössbauer Spectra of Iron(II) Hexammines. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1970, 5, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asch, L.; Shenoy, G.K.; Friedt, J.M.; Adloff, J.P.; Kleinberger, R. Mössbauer Effect and X-Ray Studies of the Phase Transition in Iron Hexammine Salts. J. Chem. Phys. 1975, 62, 2335–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, C.; Zhu, X.; Liang, J.; Qian, Y. Ferric Chloride-Graphite Intercalation Compounds as Anode Materials for Li-Ion Batteries. ChemSusChem 2014, 7, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, M.; Tashiro, R.; Washino, Y.; Toyoda, M. Exfoliation Process of Graphite via Intercalation Compounds with Sulfuric Acid. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2004, 65, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumpp, E. The Intercalation of Metal Chlorides and Bromides into Graphite. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1977, 31, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdeev, V.V.; Mukhanov, V.A.; Litvinenko, A.Y.; Semenenko, K.N. Introduction of element halides into graphite under high pressure. Bull. Mosc. Univ. Chem. Ser. II. 1984, 98, 409–412. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiarto; Minato, T.; Sakiyama, H.; Sadakane, M. Anion-Directed Conformation Switching and Trigonal Distortion in Hexakis(Methylamine)Nickel(II) Cations. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 2022, e202200386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovich, V.L.; Khavin, Z.Y. Brief Chemical Handbook, 3rd ed.; Potekhina, A.A., Efimova, A.M., Eds.; Khimiya: Leningrad, Russia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, D.L. Synthesis, Properties, and Applications of Iron Nanoparticles. Small 2005, 1, 482–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, X.; Wang, W.; Ye, Z.; Zhao, N.; Yang, H. High Saturation Magnetization of Fe3C Nanoparticles Synthesized by a Simple Route. Dye. Pigment. 2017, 139, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Synthesized GIC | Mass Fractions of Reagents, % | Synthesis Temperature T, °C | Synthesis Time t, h | Stage Number of GIC nst. | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cgr. | Metal Chloride | |||||

| GIC-FeCl3-I | 30.0 | 70.0 | 355 | 24 | I | [34] |

| GIC-FeCl3-II | 47.0 | 53.0 | 393 | 24 | II | [34] |

| GIC-FeCl3-III | 57.1 | 42.9 | 455 | 24 | III | [34] |

| GIC-FeCl3-VI | 63.9 | 36.1 | 498 | 24 | IV | [34] |

| GIC-FeCl3-V | 68.9 | 31.1 | 517 | 24 | V | [34] |

| GIC-FeCl3-VI | 72.7 | 27.3 | 523 | 24 | VI | [34] |

| GIC-FeCl3-VII | 75.6 | 24.4 | 528 | 24 | VII | – |

| GIC-CoCl2 | 33.3 | 66.7 | 450 | 96 | I–II | [35] |

| GIC-NiCl2 | 33.3 | 66.7 | 520 | 96 | II–III | [36] |

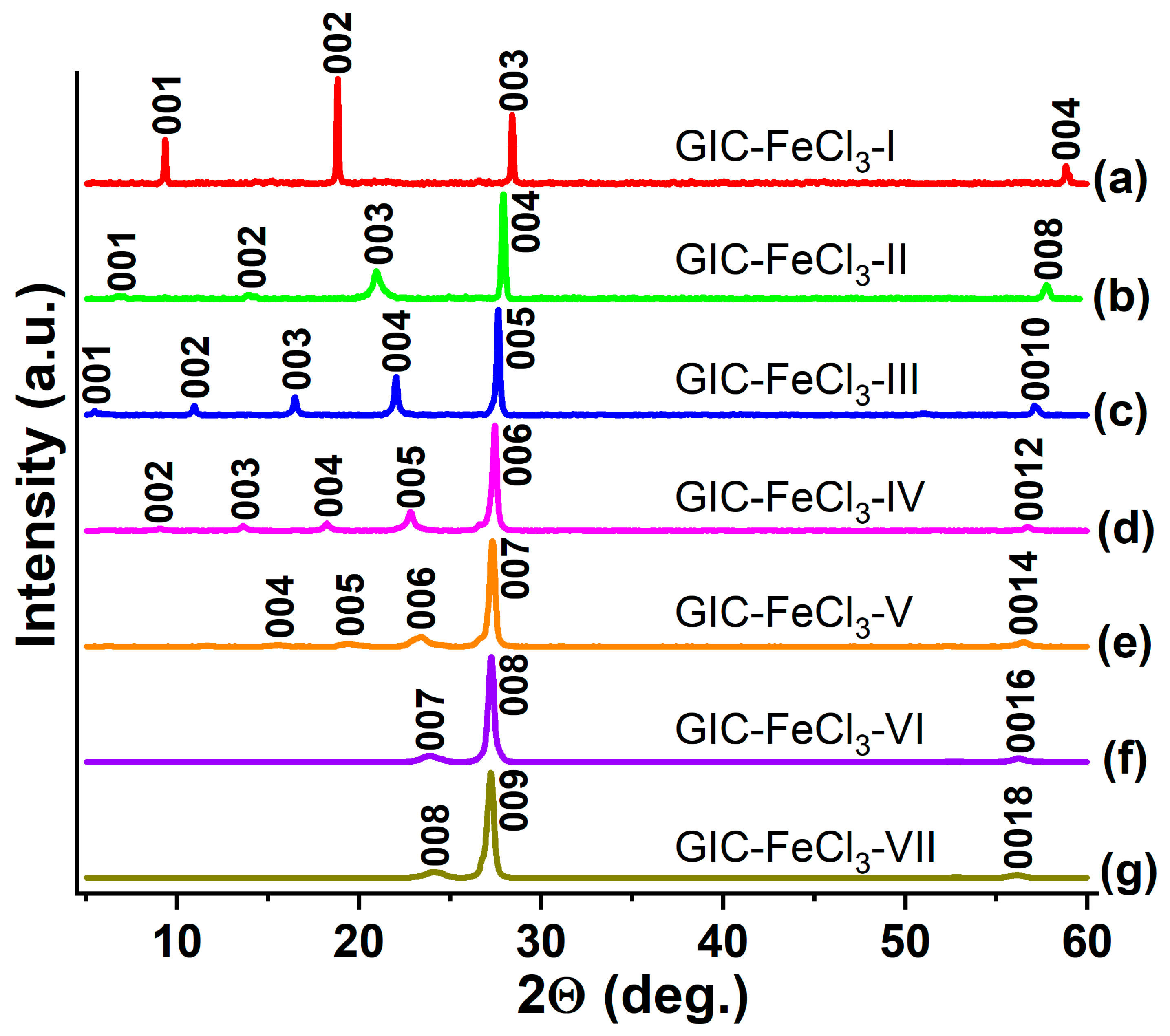

| GIC | Thickness of the Filled Layer di, Å | Period of Identity Ic, Å | Gross Composition of GIC |

|---|---|---|---|

| GIC-FeCl3-I | 9.43 ± 0.01 | 9.43 ± 0.01 | C6.0±0.5FeCl3 |

| GIC-FeCl3-II | 9.40 ± 0.05 | 12.75 ± 0.05 | C12.0±0.7FeCl3 |

| GIC-FeCl3-III | 9.43 ± 0.02 | 16.13 ± 0.02 | C18.0±0.9FeCl3 |

| GIC-FeCl3-IV | 9.43 ± 0.02 | 19.48 ± 0.02 | C24.0±1.2FeCl3 |

| GIC-FeCl3-V | 9.39 ± 0.03 | 22.79 ± 0.03 | C30.0±1.6FeCl3 |

| GIC-FeCl3-VI | 9.38 ± 0.04 | 26.13 ± 0.04 | C36.0±1.9FeCl3 |

| GIC-FeCl3-VII | 9.39 ± 0.04 | 29.49 ± 0.04 | C42.0±2.2FeCl3 |

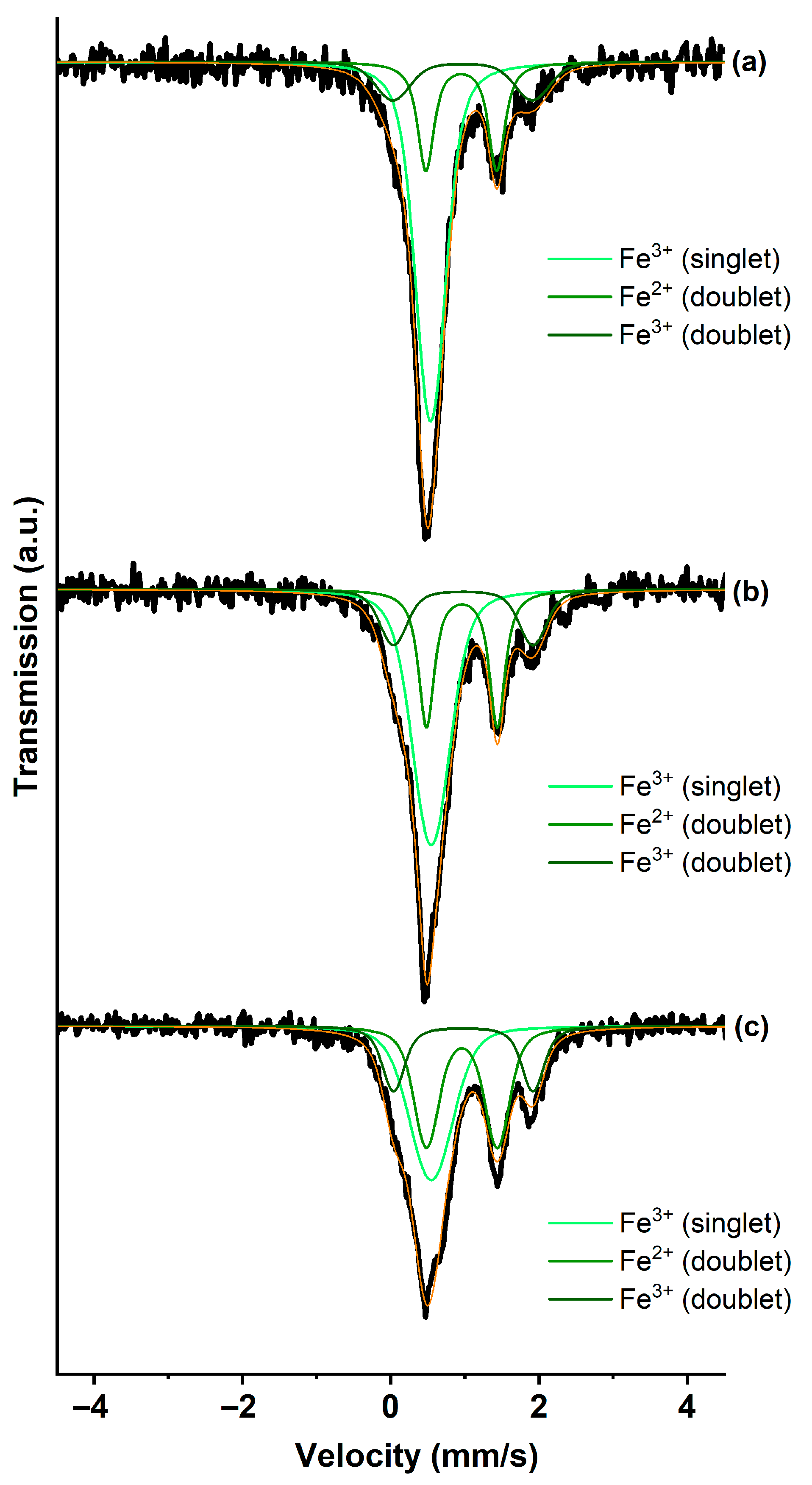

| Sample | Isomer Shift IS, mm/s | Quadrupole Splitting QS, mm/s | Area Under the Spectrum S, % | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GIC-FeCl3-I | 0.54 | 0.00 | 62 | Fe3+ (singlet) |

| 0.95 | 0.96 | 23 | Fe2+ (doublet) | |

| 0.97 | 1.88 | 15 | Fe3+ (doublet) | |

| GIC-FeCl3-II | 0.54 | 0.00 | 53 | Fe3+ (singlet) |

| 0.95 | 0.96 | 29 | Fe2+ (doublet) | |

| 0.97 | 1.88 | 18 | Fe3+ (doublet) | |

| GIC-FeCl3-III | 0.54 | 0.00 | 41 | Fe3+ (singlet) |

| 0.95 | 0.96 | 38 | Fe2+ (doublet) | |

| 0.97 | 1.88 | 20 | Fe3+ (doublet) | |

| GIC-FeCl3-I-NH3 | 1.03 | 0.00 | 27 | Fe2+ (singlet) |

| 0.35 | 0.72 | 47 | Fe3+ (doublet) | |

| 0.37 | 1.44 | 26 | Fe3+ (doublet) | |

| GIC-FeCl3-II-NH3 | 0.54 | 0.00 | 65 | Fe3+ (singlet) |

| 0.95 | 0.96 | 24 | Fe2+ (doublet) | |

| 0.97 | 1.88 | 11 | Fe3+ (doublet) | |

| GIC-FeCl3-III-NH3 | 0.54 | 0.00 | 50 | Fe3+ (singlet) |

| 0.95 | 0.96 | 30 | Fe2+ (doublet) | |

| 0.97 | 1.88 | 20 | Fe3+ (doublet) | |

| GIC-FeCl3-I-CH3NH2 | 1.03 | 1.32 | 69 | Fe2+ (doublet) |

| 0.34 | 0.73 | 31 | Fe3+ (doublet) | |

| GIC-FeCl3-II-CH3NH2 | 1.03 | 1.32 | 84 | Fe2+ (doublet) |

| 0.34 | 0.73 | 16 | Fe3+ (doublet) | |

| GIC-FeCl3-III-CH3NH2 | 1.03 | 1.32 | 81 | Fe2+ (doublet) |

| 0.34 | 0.73 | 19 | Fe3+ (doublet) | |

| FeCl3-NH3 | 1.03 | 0.00 | 11 | Fe2+ (singlet) |

| 0.35 | 0.72 | 43 | Fe3+ (doublet) | |

| 0.37 | 1.44 | 46 | Fe3+ (doublet) | |

| FeCl3-CH3NH2 | 0.34 | 0.73 | 100 | Fe3+ (doublet) |

| Stage Number of GIC-FeCl3 | RNH2 | Thermal Expansion Temperature T, °C | Bulk Density of EG dEG, g/L | Composition of the Iron-Containing Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | NH3 | 700 | 7–8 | FeCl2 · 4H2O |

| 800 | 6–7 | α-Fe | ||

| 900 | 4–5 | α-Fe | ||

| CH3NH2 | 3–4 | α-Fe | ||

| – | 60–80 | FeClx | ||

| II | NH3 | 900 | 8–9 | α-Fe, FeClx |

| CH3NH2 | 3–4 | α-Fe | ||

| III | NH3 | 900 | 10–11 | FeClx |

| CH3NH2 | 4–5 | α-Fe | ||

| IV | NH3 | 900 | 35–40 | FeClx |

| CH3NH2 | 4–5 | α-Fe, FeClx | ||

| V | NH3 | 900 | 40–45 | FeClx |

| CH3NH2 | 4–5 | α-Fe, FeClx | ||

| VI | CH3NH2 | 900 | 4–6 | α-Fe, FeClx |

| VII | CH3NH2 | 900 | 4–6 | α-Fe, FeClx |

| Methylamine Saturated | d Value (Å) for 00l Reflections | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 004 | 002 | 001 | |

| GIC-FeCl3-I | 3.88 | 7.76 | 15.52 |

| GIC-FeCl3-II | 3.88 | 7.76 | 15.52 |

| GIC-CoCl2 | 3.84 | 7.68 | 15.36 |

| GIC-NiCl2 | 3.80 | 7.66 | 15.26 |

| GIC | RNH2 | dEG, g/L | Composition of the Metal-Containing Phase |

|---|---|---|---|

| GIC-CoCl2 | – | – | CoCl2, CoCl2(int.) |

| NH3 | 4.5 | Co, CoCl2 | |

| CH3NH2 | 4 | Co | |

| GIC-NiCl2 | – | – | NiCl2(int.), NiCl2 |

| NH3 | >90 | NiCl2, NiCl2(int.), Ni | |

| CH3NH2 | 5.5 | Ni, NiCl2 |

| EG from | Total Amount of Metal-Containing Phase, ±3% | Saturation Magnetization of EG M, emu/g |

|---|---|---|

| GIC-FeCl3-NH3 | 24 | 46 |

| GIC-FeCl3-CH3NH2 | 31 | 48 |

| GIC-CoCl2-NH3 | 33 | 40 |

| GIC-CoCl2-CH3NH2 | 34 | 49 |

| GIC-NiCl2-NH3 | 25 | 4 |

| GIC-NiCl2-CH3NH2 | 23 | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muravev, A.D.; Ivanov, A.V.; Mukhanov, V.A.; Dedushenko, S.K.; Kulnitskiy, B.A.; Vasiliev, A.V.; Maksimova, N.V.; Avdeev, V.V. Effects of Preparation Conditions and Ammonia/Methylamine Treatment on Structure of Graphite Intercalation Compounds with FeCl3, CoCl2, NiCl2 and Derived Metal-Containing Expanded Graphite. Solids 2025, 6, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/solids6040060

Muravev AD, Ivanov AV, Mukhanov VA, Dedushenko SK, Kulnitskiy BA, Vasiliev AV, Maksimova NV, Avdeev VV. Effects of Preparation Conditions and Ammonia/Methylamine Treatment on Structure of Graphite Intercalation Compounds with FeCl3, CoCl2, NiCl2 and Derived Metal-Containing Expanded Graphite. Solids. 2025; 6(4):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/solids6040060

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuravev, Aleksandr D., Andrei V. Ivanov, Vladimir A. Mukhanov, Sergey K. Dedushenko, Boris A. Kulnitskiy, Alexander V. Vasiliev, Natalia V. Maksimova, and Victor V. Avdeev. 2025. "Effects of Preparation Conditions and Ammonia/Methylamine Treatment on Structure of Graphite Intercalation Compounds with FeCl3, CoCl2, NiCl2 and Derived Metal-Containing Expanded Graphite" Solids 6, no. 4: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/solids6040060

APA StyleMuravev, A. D., Ivanov, A. V., Mukhanov, V. A., Dedushenko, S. K., Kulnitskiy, B. A., Vasiliev, A. V., Maksimova, N. V., & Avdeev, V. V. (2025). Effects of Preparation Conditions and Ammonia/Methylamine Treatment on Structure of Graphite Intercalation Compounds with FeCl3, CoCl2, NiCl2 and Derived Metal-Containing Expanded Graphite. Solids, 6(4), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/solids6040060