Abstract

This article delineates the outcomes of a comprehensive analysis of occupational conditions in coal mining, focusing on dust exposure. A multifaceted model is proposed for the holistic evaluation of occupational environments, integrating risk assessment methodologies and decision-making frameworks within a risk-based paradigm. Risk assessment involved pairwise comparison, T. Saaty’s Analytic Hierarchy Process, a pessimistic decision-making approach, and fuzzy set membership functions. Correlations were established between respiratory disease risk among open pit coal mine workers and dust generation sources at the project design phase. The risk values were then validated using source attributes and particle physicochemical parameter analysis, including disperse composition and morphology. The risk assessment identified haul roads as a predominant factor in occupational disease pathogenesis, demonstrating a calculated risk level of R = 0.512. The dispersed analysis indicated the prevalence of PM1.0 and submicron particles (≤1 µm) with about 77% of the particle count, the mass distribution showed the respirable fraction (1–5 µm) comprising up to 50% of the total dust mass. Considering in situ monitoring data and particulate morphology analysis haul roads (R = 0.281) and the overburden face (R = 0.213) were delineated as primary targets for the implementation of enhanced health and safety interventions. While most critical at the design stage amidst data scarcity and exposure uncertainty, the approach permits subsequent refinement of occupational risks during operations through the incorporation of empirical monitoring data.

1. Introduction

Occupational environments inherently expose workers to hazardous agents which, through prolonged contact, induce health deterioration, specific pathologies, and trauma, leading to diminished work capacity [1,2,3]. Preserving this human capital is a socio-economic imperative, intrinsically linked to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and a core component of responsible governance [4,5,6]. The attrition of labor due to unsafe working conditions directly undermines these objectives [7], while the implementation of robust safety protocols is a critical determinant of corporate prestige and a strategic commitment to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) [8]. These imperatives demand a strategic shift from reactive to proactive risk management.

A proactive paradigm, superior to reactive approaches, employs holistic risk assessment to forecast and mitigate adverse events before they occur, thereby substantially reducing estimation errors [9,10,11]. Risk within this framework is classically defined by the constitutive dimensions of event probability and consequence severity [12]. Contemporary methodologies for occupational risk assessment encompass a broad spectrum, from quantitative to qualitative approaches, adapted across various industrial sectors [13,14,15]. A significant evolution in the field is the expanding focus on psychosocial and psychophysiological factors—such as work-related stress, fatigue, and organizational safety culture—as substantive contributors to risk etiology [16,17,18].

The mining industry represents a critical domain for such assessment, characterized by high exposure levels to deleterious agents including dust, noise, and vibration [19,20]. These exposures are directly etiologically linked to a range of specific pathologies, notably respiratory tract diseases (such as pneumoconiosis, bronchitis, cancer, etc.), musculoskeletal disorders (like degenerative joint disease, hand–arm vibration syndrome, etc.), dermatological issues (like irritant contact dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis, etc.), hearing disorders (such as noise-induced hearing loss, acoustic traumas, etc.) and many others [21,22]. The pursuit of precise risk assessment in mining has spurred extensive research focused on exposure–disease relationships, the development of risk quantification frameworks, and the pathophysiological impact of industrial hazards [23,24,25]. This risk profile is compounded in open-pit settings, where occupational and environmental factors can act synergistically, exacerbating health consequences [26].

Despite substantial research efforts, significant methodological challenges persist. Key issues include a dependency on retrospective data that obscures current exposure–health dynamics, inconsistent research outcomes, and a critical deficit of universally accepted standards, leaving a void in practical guidance [27,28,29]. A principal strategy to overcome these limitations involves the use of integrated quantitative models. These comprehensive frameworks systematically synthesize extrinsic risk factors (e.g., climatic conditions) with rigorous hygienic monitoring, medical record analysis, and professional selection criteria to achieve high-fidelity risk quantification [30,31,32]. While the aggregation of a broader set of metrics allows for a more encompassing evaluative framework [33], this augmentation introduces a fundamental trade-off: increasing model complexity can degrade predictive accuracy and robustness due to error propagation and compounding uncertainties [11].

Consequently, effective risk management in mining is contingent upon systemic prevention. This is operationalized through dedicated programs for monitoring workplace conditions and morbidity determinants, enabling the early detection of occupational diseases and informing subsequent preventive protocols [34,35]. This cycle fosters a sustainable system for risk surveillance and control. This risk-oriented approach, embedded within Occupational Safety and Health Management Systems (OSHS), is fundamentally predicated on systematic risk assessment [36]. The precise definition of risk indicators is critical, enabling informed strategic decisions to refine safety protocols and optimize workplace design [37,38], supported by a methodologically pluralistic academic discourse on risk quantification [39,40,41].

A paramount and pervasive hazard in this context is respirable dust. Particulate matter is generated across the entire mining lifecycle—from extraction and hauling to processing and storage [42]. Exposure to these aerosols is a well-established etiology for a diverse range of occupational diseases, notably afflictions of the respiratory system, skin, eyes, cardiovascular system and others [43,44], underscoring an absolute necessity for systematic dust surveillance and control. However, a pivotal disconnect remains between the recognized hazard and practical mitigation. Current approaches, whether reactive monitoring or complex integrated models, are inherently unsuited for pre-emptive action. This reveals a critical methodological gap: the absence of predictive, quantitative tools specifically designed for application during the project design and planning phase, where the most effective engineering and exposure controls could be preemptively integrated into a project.

Therefore, to bridge this gap between acknowledged risk and proactive design-phase intervention, this study develops and presents a targeted risk assessment methodology for respirable dust exposure. The proposed framework is designed for the planning stage of open-pit mining and open space bulk material handling operations. It aims to synthesize projected operational data, material characteristics, and site-specific parameters to generate a semi-quantitative estimate of exposure potential. The ultimate objective is to provide a scientifically grounded, practical decision-support tool that enables the evidence-based integration of occupational health controls directly into foundational project documentation, thereby translating the principles of proactive safety and sustainable development into actionable engineering practice.

2. Materials and Methods

A core challenge in mining engineering is ensuring safe working conditions proactively, starting from the project design phase. A significant obstacle is the inherent lack of empirical dust exposure data for a facility not yet built. Therefore, a predictive assessment of occupational aerosol exposure is required to design safer processes and integrate control measures from the outset. Under such uncertainty, where direct measurement is impossible, decision theory provides a suitable methodological foundation.

This study aims to develop a methodological framework for the predictive assessment of occupational dust exposure risks, specifically for the pre-operational design phase in mining. To support robust, risk-informed decisions, a novel assessment model based on decision theory and fuzzy logic is proposed. Its core is a synthesized procedure integrating component prioritization via the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), a pessimistic decision-making principle, rigorous data processing, and fuzzy set functions to handle qualitative uncertainty.

Decision theory offers various data collection techniques. A prominent example is the Delphi method, an iterative expert survey designed to achieve consensus [45]. However, its application is often constrained by resource intensity and high demands on expert panel competence. Other common approaches are ranking and scoring. Ranking requires a complete order of all system elements, which becomes problematic in complex systems with many similar components. Scoring assigns a quantitative value to each element against a fixed scale. Its critical weakness is evaluating components in isolation, overlooking their relative importance. This is a significant shortcoming, as interactions between elements can alter their perceived criticality within the system.

Consequently, pairwise comparison of system elements is proposed as the most suitable method for quantifying exposure to harmful industrial aerosols. This approach systematically assesses the relative significance of all components, incorporates their interaction dynamics, and yields a reliable priority ranking through mathematical synthesis. Its principal advantage is sensitivity to small but consequential differences between elements, which are often pivotal for a valid systemic evaluation.

The pairwise comparison method is implemented within the framework of the AHP. The AHP is utilized to process the research data, thereby identifying the dust emission source that contributes most significantly to the overall particulate concentration and presents the highest potential for the development of occupational diseases among workers.

In data analysis grounded in decision theory, it is critical to account for the uncertainty inherent in subjective, expert-derived data. In such contexts, the collective expert judgments form a fuzzy set. The membership function of this set quantifies the degree to which any given element belongs to it, which can be interpreted as the analyst’s confidence in assigning that element to the set.

The methodological core of the proposed model is a pessimistic approach to decision-making. This principle mandates not only a skeptical and in-depth scrutiny of inputs and outputs but also the active consideration of the most adverse potential outcomes [46]. To translate the conceptual pessimistic principle into actionable steps within the proposed risk assessment model, the following rules at key stages of data processing and analysis were implemented. These rules ensure that all uncertain parameters or expert judgments are systematically biased towards a more conservative (higher-risk) estimate.

As an example, for any input parameter with a range or uncertainty interval (e.g., measured dust concentration of 5.2 ± 0.8 mg/m3), the model automatically selects the upper-bound value (6.0 mg/m3) for all subsequent calculations. When multiple plausible exposure scenarios or physical dispersion models are applicable (e.g., different meteorological conditions), the principle mandates the selection of the scenario yielding the highest predicted exposure level for a given source.

Given that the developed methodology is designed for application in the absence of empirical data on harmful factor intensities—such as ambient dust concentrations—experts are provided with a set of objective parameters to facilitate pairwise comparisons within the AHP. This dataset includes:

- A comprehensive list of technological operations, incorporating design productivity metrics;

- Specifications of the equipment to be deployed;

- The mineralogical composition of the geological materials;

- The physico-mechanical properties of rocks and minerals, as determined from geological survey data.

Technological parameters and historical dust concentration proxies were obtained from the operational documentation of three analogous open-pit coal mines with similar meteorological conditions and equipment. Where ranges were provided, the upper bound was selected in line with the pessimistic principle. Silica content and rock hardness indices were sourced from the pre-feasibility study geological report for the projected site.

The structured expert evaluation within the AHP was conducted using a comprehensive and traceable set of input data. These data were compiled to provide experts with a consistent, realistic foundation for pairwise comparisons of dust source risks at the design stage. The inputs were categorized and sourced.

Technological and operational parameters were obtained from operational manuals, technical specifications, and project design documents from three analogous open-pit coal mining operations located in geologically similar basins. These enterprises were selected based on comparable mining methods (shovel-truck), coal seam characteristics, and climatic conditions (mean annual wind speed 5–9 m/s (mainly South–West), mean annual air temperature from +1.8 °C till −1.0 °C, etc.).

Specific data provided to experts:

- Equipment fleet and activity: Planned number and type of haul trucks (16 units of 130-ton trucks, 15 units of 220-ton trucks), excavators (hydraulic shovels, 12 m3), and their estimated daily operational cycles.

- Production and material flow: Designed annual overburden removal (60,000 m3) and coal extraction volumes (8000 tons), average haul distances from excavation faces to dumps (3.5 km)/crushers (4.5 km).

Geological and lithological data originated from the pre-feasibility study geological report for the prospective mining lease and published regional geological surveys:

- Overburden and coal seam geology: Stratigraphic column descriptions, including the thickness and areal extent of key lithological units.

- Critical geochemical parameter: Average crystalline silica (quartz) content for each major rock type (15% for coal, 55% for overburden), derived from historical borehole core analysis reported in the geological appendices.

- Material properties: General descriptors of rock hardness (for overburden: 8–10 (by M.M. Protodiakonov scale), 4 (by F. Mohs scale); for coal: 3–4 (M.M. Protodiakonov scale), 2 (F. Mohs scale)).

Particulate matter characteristics represented a synthesis of historical environmental monitoring reports from the analogous sites and published emission factors from peer-reviewed literature for standard mining activities:

- Dust concentration proxies: For each activity node (e.g., unpaved haul road travel, coal loading), experts were given a typical concentration range (e.g., 5–15 mg/m3 for background site air). These were presented as the total suspended particulate and respirable fraction estimates, clearly labeled as site-proxy data, not future measurements.

- Particle size distribution: Representative particle size distribution profiles for dust generated from key activities (e.g., mechanical crushing, wind erosion of fines). Data were presented graphically, indicating the Mass median aerodynamic diameter and the proportion of respirable fraction (<10 µm).

Presentation and caveats to the expert panel were compiled into a standardized reference dossier provided to each expert before the AHP sessions. Each data point was accompanied by: its original source; a brief note on the data type (e.g., “measured,” “calculated from emission factor,” “design value”); explicit uncertainty flags where applicable (e.g., “Based on limited sample size”, “Value represents an annual average, peak concentrations may be 2–3 times higher”).

The rationale for identifying these specific parameters as critical is grounded in current medical literature that delineates the dose–response relationship and pathogenic mechanisms of industrial dusts [47,48,49].

The model’s predictive performance was evaluated by comparing its output for an operational enterprise—previously assessed at the design stage—against actual measurements of workplace dust concentration and dust load. The degree of convergence between these two sets of results, while interpreted with specific caveats, serves to validate the methodology’s prognostic capability.

The proposed methodology is universal and applicable to a wide range of industrial facilities. For the purpose of this study, it was tested at an open-pit coal mine. Within the mine’s operational area, zones of potentially high dust generation were identified based on the ongoing technological processes. Five of these zones were subsequently prioritized as the most significant emission sources, with selection criteria including the number of employees exposed to aerosols from each source. The resulting priority zones are: crushing plant (Source 1), internal overburden dump (Source 2), overburden excavation site (Source 3), coal face (Source 4), and haul roads (Source 5).

To conduct the pairwise comparisons, five panels of five experts each were convened. The core of each group was formed by engineering and technical personnel from the enterprise, selected for their applied understanding of the relevant processes. Complementing this practical perspective, a separate cohort of research scientists was included to provide deeper theoretical insight into the mechanisms of dust formation and its chronic pathophysiological impacts. The absence of an external professional industrial hygienist in the expert panel could be considered as a study limitation. Including this expertise might improve the validity of health-related assessments in future research. The limitation was offset by inclusion of industrial and occupational safety engineers who are involved in the industrial hygiene assessment in the expert panel.

The first step in the methodology is to perform a pairwise comparison to evaluate the relative significance of all dust sources. This was accomplished using Thomas Saaty’s established nine-point scale for the AHP, which quantifies expert judgement as follows [50]:

- 1: Equal importance of the two elements;

- 3: Weak or moderate superiority of one element over the other;

- 5: Essential or strong superiority;

- 7: Demonstrated or very strong superiority;

- 9: Absolute superiority.

A fundamental tenet of the AHP is the recognition of potential data imperfections—such as incompleteness and internal inconsistency. These imperfections may include logical contradictions or relationships that deviate from the study’s framework. Consequently, within a pessimistic decision-making paradigm, a formal hypothesis test for data inconsistency must be conducted, which is operationalized through a dedicated verification step.

The primary data processing phase entails normalizing the initial pairwise comparison matrix. This is achieved by calculating the quotient of each matrix element and the sum of the elements in its corresponding column. Following normalization, the priority vector, which represents the relative weight of each element, is derived by computing the arithmetic mean (Mij) of the normalized values (Cij) across each row, as prescribed by the AHP methodology.

Here: n is the number of expert groups; i is the row number of the matrix; j is the column number of the matrix; X is the result of an expert assessment; C is the normalized value of the assessment; M is the arithmetic mean of the normalized data—the specific weight of the system component.

The pairwise comparison process can lead to inconsistencies due to the complex interdependencies among matrix elements. For instance, if an expert assigns a value of X12 = 3 (element 1 is moderately more important than element 2) and X23 = 5 (element 2 is strongly more important than element 3), logical transitivity suggests that X13 should be 5 or greater. An assignment of X13 = 3 would therefore represent a logical inconsistency. For the results to be valid, a formal consistency check of the pairwise comparisons is imperative.

Consistency is verified by computing the eigenvalues (λi) of the judgment matrix, following Equation (3). This eigenvalue is a metric for the transitivity of the pairwise comparisons. The associated principal eigenvector provides the final priority weights for the decision elements, quantifying their relative significance according to the expert data.

Eigenvalues, denoted λi, are calculated for the pairwise comparison matrix according to Equation (3) in the number of five eigenvalues (or other value of n according to the matrix). For a perfectly consistent matrix of order n, the value of λmax should be approximately equal to n. The verification procedure in Equation (4) utilizes this principle, where the deviation of the calculated λmax from the theoretical value of n is used to quantify the inconsistency of the expert judgments.

The Consistency Ratio (CR) is then determined via Equation (5). This ratio compares the calculated Consistency Index (CI) to a random index (RI), providing a standardized measure to evaluate whether the level of inconsistency in the expert judgments is within permissible limits.

where CI is calculated according to Equation (6), and RI is obtained from the T.L. Saaty scale (for n = 5 RI = 1.12) [50].

For the pairwise comparison matrix to be deemed acceptably consistent, the computed CR must be less than or equal to the threshold of 0.1, in accordance with the criterion defined by T.L. Saaty [50]. Considering the pessimistic approach in decision-making, during the consistency check of the pairwise comparison matrices, if an expert’s CR exceeds the threshold of 0.1, the matrix is not merely averaged or rejected. The revision algorithm prioritizes adjustments that increase the relative priority weight of factors associated with higher severity or lower controllability, thereby reflecting a cautious bias.

The AHP evaluation progresses through distinct phases: single hierarchy sort and total hierarchy sort. The former computes local priorities from each expert group’s judgments, while the latter aggregates these into global priorities for the entire sample. The process culminates in a verification of the overall model’s consistency.

The relative significance (specific weight) of each aerosol source for the total sample is given by the resulting [5 × 1] priority vector from the total hierarchy sort.

where i is the dust source identifier and j is the expert group identifier (matrix row index).

The aggregate specific weight, consolidating the five discrete evaluations, is determined by calculating the matrix norm. The Frobenius norm (or Euclidean norm for matrices) was chosen for this purpose, as the specific matrix form is less critical than the requirement for a comprehensive and stable measure. This choice is justified by the norm’s conceptual similarity to a root-mean-square average, its sensitivity to all input values, and its inherent robustness against anomalous data points. The Frobenius norm is chosen specifically because it mathematically aligns with a pessimistic bias: its squaring function amplifies the influence of larger (typically more severe) expert judgments during aggregation, preventing them from being diluted by averaging.

where i: dust source identifier, j: matrix row index (expert group identifier), m: total number of matrix rows, W: specific weight of the dust source within the total sort.

Translating the AHP output into a specific risk level necessitates a reference framework. For this purpose, a standardized scale for dust-related occupational risk is introduced, featuring five discrete categories: Hazardous, Harmful, Unsafe, Relatively Safe, and Safe. Each category is associated with a multiplicative weighting coefficient (K) that reflects its estimated contribution to the risk of occupational diseases development. The coefficients are scaled to ensure that more severe categories have a disproportionately stronger impact on the aggregated risk score. The “Relatively Safe” level (K = 1.0) is defined as the pivotal baseline, while the “Safe” category (K = 0.5) applies a mitigating factor to the assessment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Scale for Assessing Occupational Risk Level (compiled by authors).

It is important to note that in an active mining environment, an absolute “Safe” condition with zero exposure is unattainable. The “Safe” category was introduced to experts for broader analysis. The “Relatively Safe” category denotes an area where risk is managed to a level considered controlled under current operational and regulatory frameworks. In total, the risk category is supposed to indicate the capability of a dust source for disease development in workers, and not the absolute risk level.

Following the initial AHP methodology, the risk levels for workplaces in areas affected by dust sources are consolidated into a summary table. Based on this hazard assessment and the computed average expert score B, a fuzzy membership function f(B) is then constructed to quantify the degree of belonging to predefined risk categories. The purpose of this function is to determine the degree of membership—or the probability—that a given system component belongs to a specified fuzzy set, corresponding to a discrete risk category. The function quantifies the extent to which the calculated assessment can be legitimately assigned to a particular set interval (a subset in Table 1). This step mitigates classification ambiguity and provides a mathematical justification for the validity of the results.

Consequently, five systems of inequalities were formulated, corresponding to each workplace hazard category, as expressed in Equations (9)–(13):

where i is the dust source identifier and B is the mean risk score from AHP table for the i-th source.

The outcome of evaluating the membership degrees to the defined subsets is a matrix S of size [5 × 5]. The matrix dimensions correspond to the number of risk categories and the number of analyzed elements (dust sources). Within this membership matrix, each column vector of size [5 × 1] represents the probability distribution of a specific dust source belonging to each of the five risk categories. Thus, the columns correspond to dust sources, and the rows correspond to the risk categories starting with “Hazardous” in the 1st row.

The [1 × 5] weighting coefficient matrix K (Table 1), which encodes the risk level per category, is multiplied with the [5 × 1] columns of the membership matrix S. This computes an adjusted risk coefficient that integrates the categorical risk severity with the probabilistic membership grades, thereby accounting for assessment uncertainty.

where i is the dust source identifier.

The total attributed risk is computed by multiplying the adjusted category coefficient by the source-specific weight (Frobenius norm). This final metric reflects the proportional contribution of each dust source to occupational disease risk from hazardous aerosol exposure:

where i is the dust source identifier.

It is noteworthy that previous attempts have been made to develop risk assessment models grounded in decision theory. A similar model was proposed in the study by Zhu Z.-W. et al. [51]. The approach was also based on the integrated application of several risk assessment methods and statistical data evaluation. The authors classified threats and sources of harmful exposure to coal mine workers into three categories, according to the theory of three types of hazards, and evaluated them using the Delphi method. Subsequently, the AHP was employed to determine the specific weights of the studied components, thereby establishing priorities. Finally, using fuzzy logic, the researchers determined the final risk values for individual workplaces within the coal mine.

A key characteristic of this study, which serves as both an advantage and a limitation, is its high-level aggregation of hazard sources. This holistic perspective enables a comprehensive overview of a wide range of dangers—from physical and chemical to organizational and managerial. However, this very approach leads to a significant shortcoming: the potential synergistic effects between individual risk sources are lost within the aggregate analysis. Furthermore, the aforementioned study lacks verification of the obtained results and does not describe the foundational data upon which the experts based their evaluations. Consequently, the authors of the present article propose a different, integrated methodological approach designed to address these identified gaps.

The core innovation of the proposed methodology lies not in its individual components, but in their integrated configuration to address the specific challenge of pre-operational risk assessment. While AHP and fuzzy logic have been used separately in occupational hygiene, their combination here is uniquely tailored to synthesize sparse, analogical data from similar enterprises (where traditional statistical models fail due to lack of site-specific data) and expert judgment under high uncertainty, directly producing actionable insights for the design phase. Unlike standard AHP aggregation using arithmetic means, which can dilute extreme but critical risk warnings, the proposed adoption of a pessimistic decision principle is mathematically enforced via the Frobenius norm. This ensures that expert judgments indicating higher risk are given disproportionate weight in the group consensus, aligning the output with a precautionary, worst-case planning scenario essential for design. The risk-scaling framework moves beyond conventional hazard indices by explicitly incorporating parameters modifiable at the design stage (e.g., distance from sources, planned mitigation efficiency) into the fuzzy inference system. This creates a direct feedback loop, showing how changes in design variables affect the final risk category, which is a novel feature for proactive planning. The model introduces an unprecedented granularity in dust source characterization for pre-design analysis. Instead of treating “mining” as a monolithic source, the pairwise comparisons evaluate distinct nodes like “haul road dust resuspension,” “primary crushing,” and “wind erosion from stockpiles” separately. This granularity allows for targeted, cost-effective control strategies to be prioritized at the design phase, a significant advancement over generic recommendations.

Collectively, these innovations—pessimistic aggregation, design-sensitive risk scaling, and granular source modeling—transform the methodology from a retrospective assessment tool into a prospective decision-support system. It fills a specific gap by providing a structured, quantitative rationale for integrating dust control into engineering designs before capital commitments are made.

To confirm the method’s practical utility, its results were benchmarked against actual dust concentration in the area. The validation of potential risk in this study relied on measurements of area PM concentrations within key technological zones. These ambient data must be differentiated from personal exposure levels, a function of job location and duration. Thus, the reported concentrations are interpreted as indicators of workplace air pollution, with personal exposure monitoring recommended for future, precise evaluations of individual dose. The validation involved a series of in situ dust concentration measurements across workplace zones at an active industrial site, performed with a CEM DT-9880 airborne particle counter (manufactured by SHENZHEN EVERBEST MACHINERY INDUSTRY CO., LTD, (Brand: CEM), Shenzhen, China). The CEM DT-9880 counter is capable of performing discrete size distribution analysis of dust samples, providing a particle count distribution across individual size fractions of solid aerosols. The instrument’s sampling time is 60 s per measurement, with an air flow of 0.1 cfm (0.17 m3/h). The morphological and granulometric assessment was further conducted via electronic microscopy utilizing a CAMSIZER XT particle size analyzer (manufactured by Retsch Technology GmbH, Haan, Germany). Experimental parameters included a dust aliquot mass of 100 g, a dispersion pressure of 25–30 kPa, and an analysis cycle of 7–9 min per specimen. The resultant measurement data underwent normalization to derive specific weights relative to the aggregate particulate load, thereby establishing a metric for evaluating relative source impact and benchmarking against the prognostic assessment.

3. Results

The pairwise comparison method for assessing aerosol exposure risk in open-pit mining work zones generates a substantial volume of data. Therefore, the calculation for a single expert group will be presented hereafter for clarity, followed by a consolidated table summarizing the aggregated statistical results from all expert groups.

Table 2 presents the output from Expert Group 1, showing the relative significance assigned to each dust source. Dust sources are denoted as S1, S2, S3, S4 and S5 correspondingly to save space.

Table 2.

AHP Pairwise Comparison Matrix–EG1 (compiled by authors).

Table 3 presents the normalized matrix of the relative significance weights for the dust emission sources, derived from the data in Table 2.

Table 3.

AHP Normalized Matrix–EG1 (compiled by authors).

Subsequently, the eigenvalues for hazard sources are calculated using Equation (3).

The validation using Equation (4) confirms computational integrity, satisfying the required condition:

The CI, given by Equation (6), is then:

With five elements being evaluated, T. Saaty’s reference scale provides a RI of 1.12. Thus, the calculated CR for Expert Group 1 is 0.052. This value meets the acceptability criterion of CR ≤ 0.10, confirming the consistency of the pairwise comparisons:

The satisfactory data consistency permits their use for further prioritization of the hazard sources. Following the same methodology, the specific weight of each source is calculated, the principal eigenvalue is determined, and the consistency ratio for individual groups is established–a procedure known as single hierarchy analysis. Subsequently, the results from all groups are synthesized to calculate global priority weights and an overall consistency ratio for the entire sample, constituting total hierarchy analysis (see Table 4).

Table 4.

AHP-Based Analysis of Data Integrity and Component Weights (compiled by authors).

Source 4 (coal face) and Source 5 (haul roads) were identified as the predominant industrial aerosol sources (w: single-group weight; W: global weight). Therefore, occupations with direct exposure to these areas—such as excavator and truck operators, face workers, and technical supervisors—are positioned within the highest risk category for occupational lung disease development.

To quantify the contribution of each source to the aggregate risk, their specific weights are recalibrated. This recalibration involves computing the Frobenius norm for every source based on the results of the total hierarchy synthesis, as defined by Equations (7) and (8). The procedure is illustrated below for Source 1:

The resulting integrated specific weights for Sources 1–5 are 0.025, 0.036, 0.049, 0.110, and 0.237, respectively.

The progression of the Frobenius norm values (from 0.025 for Source 1 to 0.237 for Source 5) provides insight into the expert evaluation process. The increasing norm indicates greater divergence in expert judgments and higher estimated values for higher-risk sources. This is operationally logical: assessing complex, variable sources like haul roads inherently involves more uncertainty and differing professional perspectives compared to a confined process like a crushing plant.

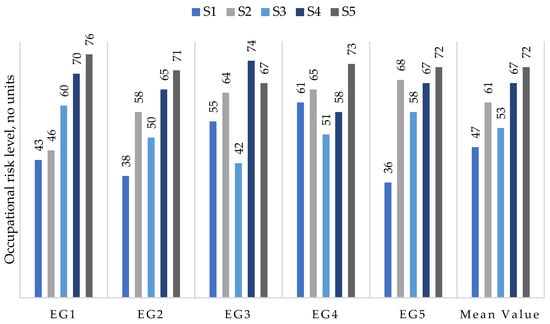

The expert assessment results of the dust exposure hazard level across work zones, based on the proposed scale, are presented via histogram in Figure 1. The mean hazard ratings for Sources 1–5 are 47, 61, 53, 67, and 72, respectively.

Figure 1.

Occupational risk level assessment (compiled by authors).

To evaluate the degree of membership in the predefined fuzzy subsets, the five mean risk values per source were processed using membership Equations (9)–(13). The output is structured as a matrix, with columns sequentially representing the dust sources and rows representing the expert groups.

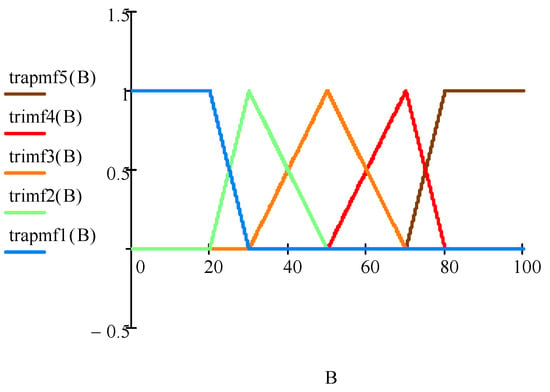

For enhanced visualization, the membership functions of the fuzzy sets are presented graphically in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Fuzzy set membership functions (compiled by authors). Here: trapmf—is a trapezoidal membership function; trimf—a triangular membership function.

Subsequently, according to Equation (14), the multiplication of the weighting coefficient by the columns of matrix S yields the corrected coefficient values.

The corrected hazard coefficients (Kcorr) quantify the amplified risk severity. The coefficient for haul roads (Kcorr−5 = 2.2) is the highest, meaning that exposure here is judged to be more than twice as harmful as the baseline for the “Relatively safe” source when considering the complexity of exposure potential.

The risk level, Ri for each source (where i is the source identifier) is calculated as the product of the adjusted coefficient, Kcorr, and the Frobenius norm of the respective source.

The calculated risk scores reveal a clear hierarchy of dust sources at the projected operation. Source 5 (haul roads) presents the highest risk (R5 = 0.512), followed by Source 4 (coal face) (R4 = 0.212). The operational rationale for this ranking is evident: haul roads are characterized by continuous, high-frequency vehicle traffic, which generates and resuspends dust across vast, open areas with limited options for effective containment. Similarly, the active coal face involves intensive mechanical excavation in a concentrated zone, leading to high dust liberation.

The magnitude of the differences is critical for risk prioritization. The risk from haul roads (R5 = 0.512) is more than double that of the coal face and an order of magnitude greater than the crushing plant (R1 = 0.036). This is not a linear scale but indicates that haul roads constitute the dominant, pervasive risk driver for the entire site. Consequently, control strategies must be fundamentally different: for haul roads, site-wide measures (e.g., comprehensive road watering systems, reduced speed limits, chemical dust suppressants) are imperative, while for other sources, localized engineering controls may suffice.

4. Discussion

Analysis of the risk values (R1–R5) identifies haul roads (Source 5) as the dominant contributor to both particulate concentration and associated occupational exposure risk. The justification lies in the heterogeneous nature of the road dust, characterized by a wide range of particle sizes, shapes, and mineral compositions, which is aerosolized by continuous vehicle operation. Logistically, the aerial extent of the haulage routes, covering more than 80% of the pit’s footprint, further substantiates their preeminence over more localized sources such as excavation faces, establishing them as the paramount dust source in the open-pit environment.

The risk assessment identifies Source 5 (haul road dust) as a primary contributor, in the model, demanding the highest priority for control measures. The specific risk score quantified for this exposure zone is 0.512.

It is critical to emphasize that the calculated risk indices (Ri) are relative, unitless scores derived from the multi-criteria decision model. They are not direct measures of disease incidence or absolute probability but serve to rank sources by their potential contribution to overall exposure risk, facilitating prioritization.

The crushing plant area (Source 1) was identified as the safest work zone, presenting the lowest impact from respirable fibrous dust with a minimal relative risk value of 0.036. In contrast, the areas influenced by haul roads (Source 5) were the most hazardous, with a maximum risk value of 0.512.

During the deposit design phase, it is challenging to account for all factors influencing the degree of harmful fibrogenic and toxic effects on workers. However, certain parameters can be forecasted, such as the prevailing wind pattern for modeling dust dispersion and the approximate dust chemical composition based on geology survey. Consequently, the comprehensiveness of the scientific and technical data incorporated into the analysis directly correlates with the accuracy of the risk assessment. While the proposed framework offers a proactive tool for design-phase assessment, several limitations inherent to its approach should be acknowledged. The model’s outputs are contingent upon expert elicitation, introducing subjectivity, although the use of the fuzzy logic, Frobenius norm and pessimistic principle aimed to formalize this bias conservatively. Furthermore, the reliance on proxy data from analogous enterprises for activity levels and dust generation potentials is a necessary substitution in the absence of site-specific measurements, but it adds a layer of uncertainty to the predictions. The risk scores (Ri) should therefore be interpreted as relative indicators for prioritization rather than absolute measures of health outcome probability. Finally, the model simplifies complex aerosol dispersion and exposure dynamics; future iterations could be strengthened by integrating computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations for critical zones like haul roads to refine spatial risk estimates.

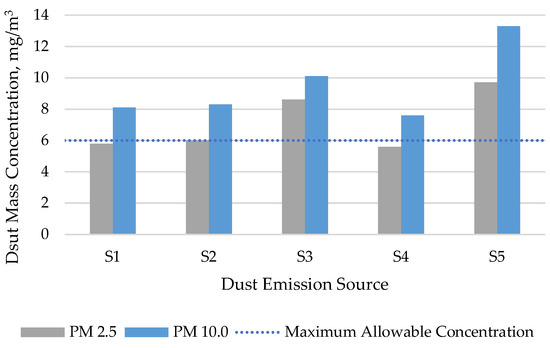

Given that the proposed risk assessment methodology relied on proxy data from similar facilities in the absence of direct dust concentration measurements, its applicability requires validation against empirical exposure levels. To this end, a measurement campaign was undertaken to quantify dust concentrations in work zones affected by the key emission sources. Figure 3 presents the measured airborne dust levels, while Table 5 details the corresponding particle size distributions.

Figure 3.

Workplace Airborne Dust Concentrations per Size Fraction (compiled by authors).

Table 5.

Airborne Dust Particle Size Distribution in Workplace Areas (compiled by authors).

The highest occupational disease potential from dust was associated with the overburden face (Source 3; C = 10.1 mg/m3, exceeding the 6 mg/m3 Maximum Allowable Concentration–MAC) and haul roads (Source 5; C = 13.3 mg/m3, consistently exceeding MAC). MACs represent the permissible ambient concentrations of coal dust and silica dust in the working area, with both values of 6 mg/m3. The values are stated according to Hygienic Standards GN 2.2.5.3532-18 “Maximum Allowable Concentrations (MAC) of Hazardous Substances in Workplace Air” (approved by Resolution No. 25 of the Chief State Sanitary Physician of the Russian Federation, dated 13 February 2018). The risk at Sources 3 and 5 is compounded by significant spatial concentration gradients posing a serious threat for areas in the predominant wind directions.

The granulometric analysis indicates a dust profile with high respiratory risk. The measured particle number size distribution shows a unimodal log-normal profile with a peak in the submicron range (<1 μm, 77% of total count). However, considering the site-specific emission sources (diesel equipment, mechanical rock and coal crushing, blasting), this profile likely represents a superposition of two distinct aerosol fractions.

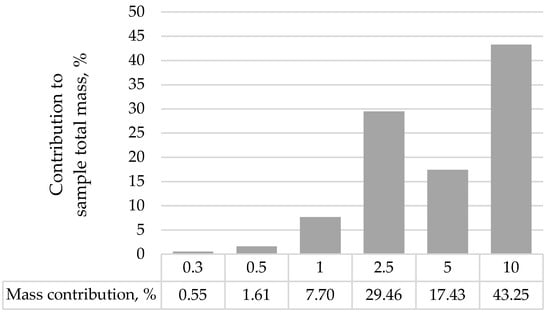

The mass distribution, calculated from number data, was distinctly bimodal (Figure 4). About 50% of the mass was in the 2.5–5.0 μm range, with ~43% from 10 μm particles—a size of lesser importance for respirable risk. The ultrafine fraction (<1 μm), dominant in number, contributed negligibly to mass but may have high specific biological activity due to extensive surface area and number. Conversion to mass distribution confirms a significant contribution from the micron-sized fraction.

Figure 4.

Dust Mass Distribution per Size Fraction in μm (compiled by authors).

The AHP-based prioritization of dust emission sources, using measured dust concentrations, yields the following relative weights for the dust generation sources:

- Source 1: 0.171;

- Source 2: 0.175;

- Source 3: 0.213;

- Source 4: 0.160;

- Source 5: 0.281.

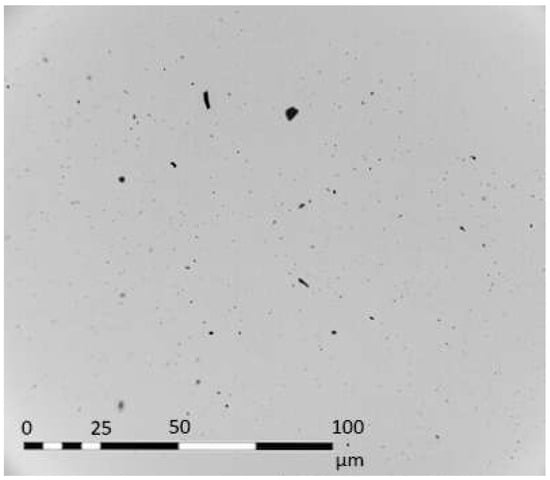

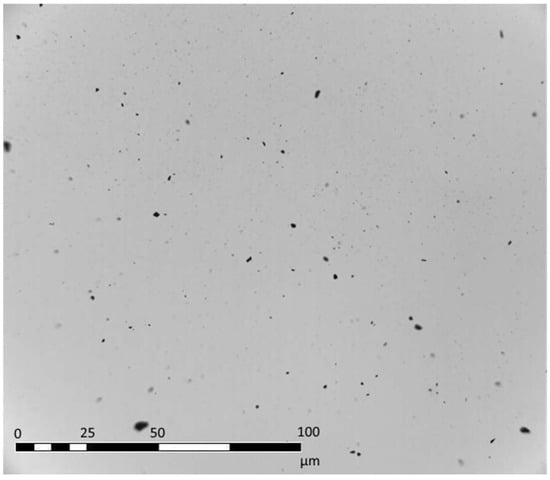

Electron microscopic analysis of particle morphology indicates that shape varies significantly with the mining operation stage, genesis mechanism, and mineralogy. Particulate matter from the overburden face and haulage routes (Figure 5 and Figure 6) demonstrates a pronounced fibrogenic potential. The heightened pathogenicity is linked to the sharp, needle-like form of the dominant respirable crystalline silica fraction, which facilitates alveolar deposition and lung tissue traumatization.

Figure 5.

Dust particles microscopic analysis—Source 3 (compiled by authors).

Figure 6.

Dust particles microscopic analysis—Source 5 (compiled by authors).

A key determinant of the studied dust’s fibrogenic profile is crystalline silica (typically as quartz). Its presence in the respirable fraction of overburden and haul road dust is the primary driver of silicosis risk.

Pathogenicity is exacerbated by particle morphology. The sharp, angular form promotes deep alveolar deposition and direct physical damage to macrophage and epithelial cell membranes. This “surface reactivity” initiates a potent cycle of inflammation, necrosis, and pro-inflammatory cytokine release (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β), leading to progressive fibrosis.

Therefore, risk assessment must shift to silica-specific metrics. The critical indicator is the respirable crystalline silica (RCS) content, not just total dust mass. This necessitates stricter exposure limits. Standards vary: for coal dust with >5% SiO2, OSHA uses a calculated limit; for <5%, it is 2.4 mg/m3. NIOSH recommends 0.9–1 mg/m3 depending on measurement method. Russian GN 2.2.5.3532-18 grade limits based on coal type: 10 mg/m3 (coals except for anthracite, SiO2 < 5%), 6 mg/m3 (anthracite, SiO2 < 5%). For crystalline silica dust, limits are far stricter: 25 µg/m3 (OSHA, 8-h time weighted average), 50 µg/m3 (NIOSH), and according to GN 2.2.5.3532-18: 4 mg/m3 (2–10% of silica), 2 mg/m3 (10–70%), and 1 µg/m3 (>70%).

The predominance of the 2.5–5.0 µm fraction (Figure 4) is critical, as this size is optimal for alveolar deposition of highly abrasive quartz particles. Even moderate, prolonged exposure poses an unacceptable risk, making the measurement results concerning. Thus, control measures (e.g., wet suppression for respirable dust, high-efficiency respirators) must specifically target silica.

Data on dust concentration and properties identify the overburden face (Source 3) and haul roads (Source 5) as high-risk zones for occupational exposure and disease potential, with Source 5 being paramount. These results align with risk assessment, confirming the prognostic model’s prediction of their dominant contribution to the ambient particulate concentrations and to the workers’ health risks.

Moreover, the research findings resonate with and extend prior research. The identification of haul roads as the predominant risk source (R5 = 0.512) aligns with empirical studies highlighting vehicle traffic as a major contributor to respirable dust in open-pit mines [52]. However, most existing studies quantify this through post hoc monitoring [52,53]. The novelty of our work lies in providing a predictive, comparative quantification of this risk before operations begin, using a transferable methodological framework rather than site-specific monitoring data.

Unlike conventional hazard indices that often treat dust as a generic agent, the proposed source-specific granularity (e.g., separating primary crushing from haul road resuspension) allows for more targeted intervention planning, a step forward from the recommendations in broader risk-screening tools [54]. The pessimistic approach formalizes a precautionary stance that is often mentioned but rarely algorithmically enforced in similar multi-criteria models for occupational health.

These methodological choices directly inform practice: the results mandate that control strategy design must be hierarchical, with site-wide, systemic measures for high-score, pervasive sources like haul roads, and localized engineering solutions for confined processes. This provides a rational basis for allocating limited safety budgets during project planning.

The results largely corroborate the initial prognosis, although a discrepancy is noted for the coal face (Source 4). Additionally, the apportionment of specific weights according to the measured dust load demonstrates a more even distribution among all sources than was predicted by the model. The alignment of risk assessment outcomes, when applying this methodology at different stages of a mine’s lifecycle, is not static. It is influenced by dynamic factors including technological progress in extraction and processing, improvements in worker safety protocols, and even shifts in climatic patterns. Consequently, a degree of discrepancy between the occupational risk assessments conducted at the project design phase and the operational phase is to be expected, even when applying the same methodology. This finding, however, underscores the necessity of refining and adapting risk assessment frameworks to align with the specific lifecycle stage of the enterprise.

The gathered data indicate that exposure levels across all monitored operational zones warrant improved control measures. While the highest risk was identified at the haul roads and overburden face (mandating immediate and targeted actions), continuous dust suppression and administrative controls are recommended for the entire site to ensure comprehensive worker protection.

The feasibility and effectiveness of these strategies vary significantly. A comparative feasibility assessment highlights practical challenges. Utilization of enclosed spaces is a highly plausible and established engineering control. Modern cabs of excavators, bulldozers and haul trucks with positive pressure and HEPA filtration can reduce in-cab respirable dust by over 90%. This solution targets the largest worker group at the epicenter of the risk source, offering high impact and operational continuity. Nevertheless, the sealing elements and filter system consumables tend to wear intensively, especially in highly dusty conditions, which necessitates timely control and replacement. Moreover, the filtration efficiency is mostly limited by the maximum size of 0.3 µm of filtered matter and thus does not incorporate the whole submicron fraction.

In contrast, surveyors, blasting engineers, geologists and other field workers are directly exposed to particulate matter and cannot be enclosed in a filtered cabin space. Thus, their effective protection presents greater challenges. Without a fixed enclosure, reliance on personal protective equipment (PPE), specifically high-efficiency respirators, becomes paramount. However, PPE efficacy depends on consistent proper use and timely replacements, fit-testing, and compliance, which are harder to guarantee in isolated, mobile tasks.

Additionally, proper dust control mechanisms may provide safer conditions. Organization of timely watering of dusty surfaces may be of great importance, especially for haul roads. Implementation of specific and highly effective dust suppression measures, for example, utilization of chemical dust suppressants or constructing wear-resistant haul roads using geotextile, is limited due to the ecological risks or high expenditures of such approach. Therefore, while comprehensive approach is necessary, the engineering control for in-cabin operators represents a more immediately achievable and reliable primary barrier, followed by administrative controls (e.g., limiting time on the pile or surface watering mode) and rigorous PPE programs for surface workers.

5. Conclusions

The pursuit of enhanced productivity in mining operations amplifies the risk profile associated with intensive occupational exposures. The proliferation of particulate matter in mining, open-pit, and coal terminal environments represents a significant and persistent challenge. Occupational morbidity contributes to the deterioration of socio-economic status, a loss of workforce productivity, and long-term disability, alongside incurring substantial employer liabilities. As a result, the strategic integration of exposure control measures has emerged as a cornerstone of modern occupational health and industrial safety management frameworks.

At the project design stage for mineral resource developments, characterized by uncertainty and an absence of empirical data on hazardous exposures, identifying effective safety interventions is exceptionally difficult. Without employing specialized predictive tools and methods, this task approaches the impractical.

To address this challenge, the authors have developed a comprehensive semi-quantitative risk assessment framework for determination of potential dust-induced risks. This model synthesizes several methodological approaches: the Analytic Hierarchy Process for pairwise element evaluation, a pessimistic decision-making approach to test hypotheses on data consistency and integrity, and the fuzzy set theory to incorporate the inherent stochasticity of the input parameters.

The analytical results identified haul roads as the predominant source of occupational risk from industrial aerosols at the mine site, accounting for more than 50% of the aggregate risk of occupational pathology. In this context, the term ‘industrial aerosols’ primarily refers to the complex mixture of mechanically generated coal and silica-rich rock dust, amplified by diesel exhaust particles. This combination dictates a multi-faceted control approach. The primary causative factors include the dense circulation of haulage vehicles, the high-energy processes involved in rock fragmentation and handling, and complex physicochemical characteristics of the liberated dust. Therefore, the risk management plan should prioritize the implementation and maintenance of sealed, filtered cabins for vehicles as the most feasible and effective primary control. This must be supplemented by a comprehensive program of administrative controls and enforced PPE use for personnel in other high-exposure areas, such as the overburden face.

Subsequent work will focus on enhancing the model’s robustness through the implementation of a multi-factorial risk scale, tailored to source-specific attributes. These refined metrics will be integrated as calibration factors to quantify the aggregate harmful load on personnel. The study also explores leveraging the model’s assessments for operational area zoning and advancing towards a fully parameterized system for industrial hygiene surveillance. Moreover, the development of a reference scale for occupational risk levels based on prioritization results might be an object of interest for further research to provide reasonable and informed decision-making.

The methodology facilitates the early identification of critical emission sources at the project design stage, providing an evidence-based rationale for implementing targeted safety interventions. Furthermore, the model’s framework allows for the quantification of individual source contributions to occupational morbidity and possesses the inherent scalability to evaluate the combined effects of diverse industrial hazards, including noise, vibration, and ergonomic stress, on overall health risk.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.K. and S.K.; methodology, I.I.; software, I.I.; validation, I.I. and S.K.; formal analysis, G.K.; investigation, I.I.; resources, S.K.; data curation, I.I. and S.K.; writing—original draft preparation, I.I.; writing—review and editing, I.I. and S.K.; visualization, I.I.; supervision, G.K. and S.K.; project administration, S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by The Commission for the Review of Scientific, Educational, Methodological, and Intellectual Property Materials of Empress Catherine II Saint Petersburg Mining University (protocol 2024-12-01c from 23 December 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AHP | Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| CI | Consistency Index |

| CR | Consistency Ratio |

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility |

| EG | Expert Group |

| MAC | Maximum Allowable Concentration |

| NIOSH | National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health |

| OSHA | Occupational Safety and Health Administration |

| OSHS | Occupational Safety and Health Management System |

| RI | Random Consistency Index |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| trapmf | Trapezoidal Membership Function |

| trimf | Triangular Membership Function |

References

- Shojaee Barjoee, S.; Rodionov, V.; Babkin, R.; Tumanov, M.; Shojaee Barjoee, B. An Integrated Modified Failure Mode Effects Analysis Shannon Entropy Combined Compromise Solution Approach to Safety Risk Assessment in Stone Crusher Unit of Ceramic Sector. Int. J. Eng. 2026, 39, 1976–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetzlaff, E.J.; Goggins, K.A.; Pegoraro, A.L.; Dorman, S.C.; Pakalnis, V.; Eger, T.R. Safety Culture: A Retrospective Analysis of Occupational Health and Safety Mining Reports. Saf. Health Work 2021, 12, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodoo, J.E.; Al-Samarraie, H. A systematic review of factors leading to occupational injuries and fatalities. J. Public Health 2023, 31, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvinenko, V.S.; Petrov, E.I.; Vasilevskaya, D.V.; Yakovenko, A.V.; Naumov, I.A.; Ratnikov, M.A. Assessment of the role of the state in the management of mineral resources. J. Min. Inst. 2023, 259, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, G.; Qi, T.; Guangzhu, J. Labor protection and the efficiency of human capital investment. Econ. Anal. Policy 2021, 69, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, Y.; Fu, X. Labor Protection, Enterprise Innovation, and Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evkhuta, N.A.; Zharikova, O.S.; Zilberbrand, N.Y. State Policy of the Russian Federation in the Field of Human Capital Development at the Present Stage. Econ. Sci. 2023, 222, 142–146. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvinenko, V.S.; Bowbrick, I.; Naumov, I.A.; Zaitseva, Z. Global guidelines and requirements for professional competencies of natural resource extraction engineers: Implications for ESG principles and sustainable development goals. J. Cleaner Prod. 2022, 338, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Cheung, C.; Manu, P.; Ejohwomu, O.; Sol, J.T. Implementing safety leading indicators in construction: Toward a proactive approach to safety management. Saf. Sci. 2023, 157, 105929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikulin, A.N.; Krasnoukhova, D.Y.; Stepanova, L.V.; Burlov, V.G.; Gomazov, F.A. Organizational and technical measures to reduce the value of industrial noise on the underground coal miners. MIAB. Min. Inf. Anal. Bull. 2022, 6–1, 157–173. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabanov, E.I. Allowable occupational injury risk assessment in coal mining industry. MIAB. Min. Inf. Anal. Bull. 2022, 5, 167–180. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajnburg, G.Z.; Rozenfel’d, E.A. Development of a methodology for assessing the cumulative risk of a complex of hazards of underground mining enterprises. News Tula State Univ. Sci. Earth 2023, 1, 108–125. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanka, K.S.; Shukla, S.; Gomez, H.M.; James, C.; Palanisami, T.; Williams, K.; Horvat, J.C. Understanding the pathogenesis of occupational coal and silica dust-associated lung disease. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2022, 31, 210250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaykhlislamova, E.R.; Karimova, L.K.; Beigul, N.A.; Muldasheva, N.A.; Fagamova, A.Z.; Shapoval, I.V.; Volgareva, A.D.; Larionova, E.A. Occupational health risk for workers from basic occupational groups employed at copper and zinc ore mining enterprises: Assessment and management. Health Risk Anal. 2022, 2, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuang, L.; Mengjie, Y.; Dingwei, L.; Jiao, L. Identifying coal mine safety production risk factors by employing text mining and Bayesian network techniques. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 162, 1067–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glebova, E.V.; Volokhina, A.T.; Vikhrov, A.E. Assessment of the efficiency of occupational safety culture management in fuel and energy companies. J. Min. Inst. 2023, 259, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setko, N.P.; Movergoz, S.V.; Bulycheva, E.V. Features of the functional state of professionally significant body systems of operators and machinists of a petrochemical enterprise depending on their work experience. Russ. J. Occup. Health Ind. Ecol. 2020, 1, 25–29. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundström, E.; Nygren, M. Safety Initiatives in Support of Safety Culture Development: Examples from Four Mining Organisations. Min. Metall. Explor. 2023, 40, 1007–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebotarev, A.G.; Pfaf, V.F.; Gibadulina, I.Y. Current State of Labour Conditions, Occupational Morbidity and Improvement of Medical and Preventive Care for Employees of Mining Operations. Russ. Min. Ind. 2021, 3, 139–143. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korshunov, G.I.; Krasnoukhova, D.Y. Substantiation of a Comprehensive Approach for Evaluating Traumatic Incidents, Considering the Human Factor. Int. J. Eng. Trans. C Asp. 2026, 39, 1482–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myasnikov, I.O.; Kizeev, A.N. Risks of developing occupational and production related diseases in workers of mining and metallurgical enterprises in the Russian Arctic. Russ. Arct. 2024, 6, 26–42. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyakova, E.M.; Meltser, A.V.; Iakubova, I.S.; Erastova, N.V.; Suvorova, A.V. Integrated model of health risk assessment for workers having to work outdoors under exposure to cooling meteorological factors. Health Risk Anal. 2022, 2, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodionov, V.A.; Skripnik, I.L.; Ivakhnyuk, S.G. Investigating Properties of Hard Coal Spontaneous Ignition. Occup. Saf. Ind. 2025, 4, 7–13. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubakirov, S.M. Medical examinations as a factor of early detection of occupational and general somatic diseases. Zdravoohr. Jugry Opyt Innovacii 2022, 1, 72–74. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Rudakov, M.L.; Babkin, R.S.; Medova, E.A. Improvement of Working Conditions of Mining Workers by Reducing Nitrogen Oxide Emissions during Blasting Operations. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitseva, N.V.; Shur, P.Z.; Alekseev, V.B.; Savochkina, A.A.; Savochkin, A.I.; Khrushcheva, E.V. Methodical approaches to assessing categories of occupational risk predetermined by various health disorders among workers related to occupational and labor process factors. Health Risk Anal. 2020, 4, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubis, A.; Werbińska-Wojciechowska, S.; Sliwinski, P.; Zimroz, R. Fuzzy Risk-Based Maintenance Strategy with Safety Considerations for the Mining Industry. Sensors 2022, 22, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutor, E.M.; Zhidkova, E.A.; Gurevich, K.G.; Zibarev, E.V.; Vostrikova, S.M.; Astanin, P.A. Some approaches and criteria for assessing the risk of developing occupational diseases. Russ. J. Occup. Health Ind. Ecol. 2023, 63, 94–101. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigaud, M.; Buekers, J.; Bessems, J.; Basagaña, X.; Mathy, S.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; Slama, R. The methodology of quantitative risk assessment studies. Environ. Health 2024, 23, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazaluk, O.; Tsopa, V.; Okrasa, M.; Pavlychenko, A.; Cheberiachko, S.; Yavorska, O.; Deryugin, O.; Lozynskyi, V. Improvement of the occupational risk management process in the work safety system of the enterprise. Front. Public Health 2024, 11, 1330430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korshunov, G.I.; Mironenkova, N.A.; Poleshchuk, A.A. The topical methods of detecting spontaneous combustion sources in coal mines. Min. Inf. Anal. Bull. 2025, 5, 169–180. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendler, S.G.; Bratskih, A.S. Actual problems of coal accumulations ignition in rock dumps. Russ. Min. Ind. 2024, 5S, 71–77. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karchina, E.I.; Ivanova, M.V.; Volokhina, A.T.; Glebova, E.V.; Vikhrov, A.E. Improving the procedure for group expert assessment in the analysis of professional risks in fuel and energy companies. J. Min. Inst. 2024, 270, 994–1003. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L.H.; Cao, D.Q.; Guo, H.M. Analysis of coal mine occupational disease hazard evaluation index based on AHP-DEMATEL. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2021, 76, 372–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffari, S.; Heibati, B.; Jaakkola, M.S.; Lajunen, T.K.; Kalteh, S.; Alimoradi, H.; Nazari, M.; Karimi, A.; Jaakkola, J.J.K. Effects of occupational exposures on respiratory health in steel factory workers. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1082874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirniakova, V.V.; Smirniakov, V.V.; Almosova, Y.V.; Kargopolova, A.P. «Vision Zero» Concept as a Tool for the Effective Occupational Safety Management System Formation in JSC «SUEK-Kuzbass». Sustainability 2021, 13, 6335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.; Yao, N. Hazard identification, risk assessment and management of industrial system: Process safety in mining industry. Saf. Sci. 2022, 154, 105863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P.; Carneiro, M.; Costa, N.; Loureiro, I.; Carneiro, P.; Pires, A.; Ferreira, C. Development and Application of an Integrated Index for Occupational Safety Evaluation. Safety 2024, 10, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustyuganova, V.V.; Kovalkovskaya, N.O.; Serdyuk, V.S.; Fomin, A.I. Choice of a method for forecasting professional risks in the mining industry. Bull. Sci. Cent. VostNII Ind. Environ. Saf. 2020, 4, 46–55. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, W.; Yang, W.; Huang, B.; Wang, Z.; Tian, S. Occupational Risk Prediction for Miners Based on Stacking Health Data Fusion. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabanov, E.I.; Tumanov, M.V.; Smetanin, V.S.; Romanov, K.V. An innovative approach to injury prevention in mining companies through human factor management. J. Min. Inst. 2023, 263, 774–784. [Google Scholar]

- Gendler, S.G.; Stepantsova, A.Y.; Popov, M.M. Justification on the safe exploitation of closed coal warehouse by gas factor. J. Min. Inst. 2024, 272, 72–82. [Google Scholar]

- Rumchev, K.; Van Hoang, D.; Lee, A.H. Exposure to dust and respiratory health among Australian miners. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2023, 96, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keer, S.; Brooks, C.; Glass, B.; McLean, D.; Harding, E.; Douwes, J. Respiratory symptoms and use of dust-control measures in New Zealand construction workers—A cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0266668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Li, C.; Li, X.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, X. Comprehensive Evaluation System of Occupational Hazard Prevention and Control in Iron and Steel Enterprises Based on A Modified Delphi Technique. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeunen, O.; Goethals, B. Pessimistic Decision-Making for Recommender Systems. ACM Trans. Recomm. Syst. 2022, 1, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, K.; Jerome, J. Silicosis. Workplace Health Saf. 2021, 69, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, J.T.; Cool, C.D.; Green, F.H.Y. Pathology and Mineralogy of the Pneumoconioses. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 44, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cool, C.D.; Murray, J.; Vorajee, N.I.; Rose, C.S.; Zell-Baran, L.M.; Sanyal, S.; Cohen, R.A. Pathologic Findings in Severe Coal Workers’ Pneumoconiosis in Contemporary US Coal Miners. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2024, 148, 805–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. Theory and Applications of the Analytic Network Process: Decision Making with Benefits, Opportunities, Costs, and Risks; RWS Publications: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.-W.; Shi, Y.-K.; Qin, G.-P.; Bian, P.-Y. Research on the Occupational Hazards Risk Assessment in Coal Mine Based on the Hazard Theory. Procedia Eng. 2011, 26, 2157–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, F.G.; Xiang, L.; Yang, Z.; Gebretsadik, A.; Wahab, A.; Fissha, Y.; Cheepurupalli, N.R.; Sazid, M. Research on Dust Concentration and Migration Mechanisms on Open-Pit Coal Mining Roads: Effects of Meteorological Conditions and Haul Truck Movements. Mining 2025, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, C.; Cauda, E.; Yekich, M.; Patts, J. Real-Time Dust Monitoring in Occupational Environments: A Case Study on Using Low-Cost Dust Monitors for Enhanced Data Collection and Analysis. Min. Metall. Explor. 2024, 41, 1709–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Zhou, W.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, X.; Yan, J.; Wang, R.; Li, Y.; Lu, X. Study on Dust Hazard Levels and Dust Suppression Technologies in Cabins of Typical Mining Equipment in Large Open-Pit Coal Mines in China. Atmos. 2025, 16, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).