Fungal Guilds Reveal Ecological Redundancy in a Post-Mining Environment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

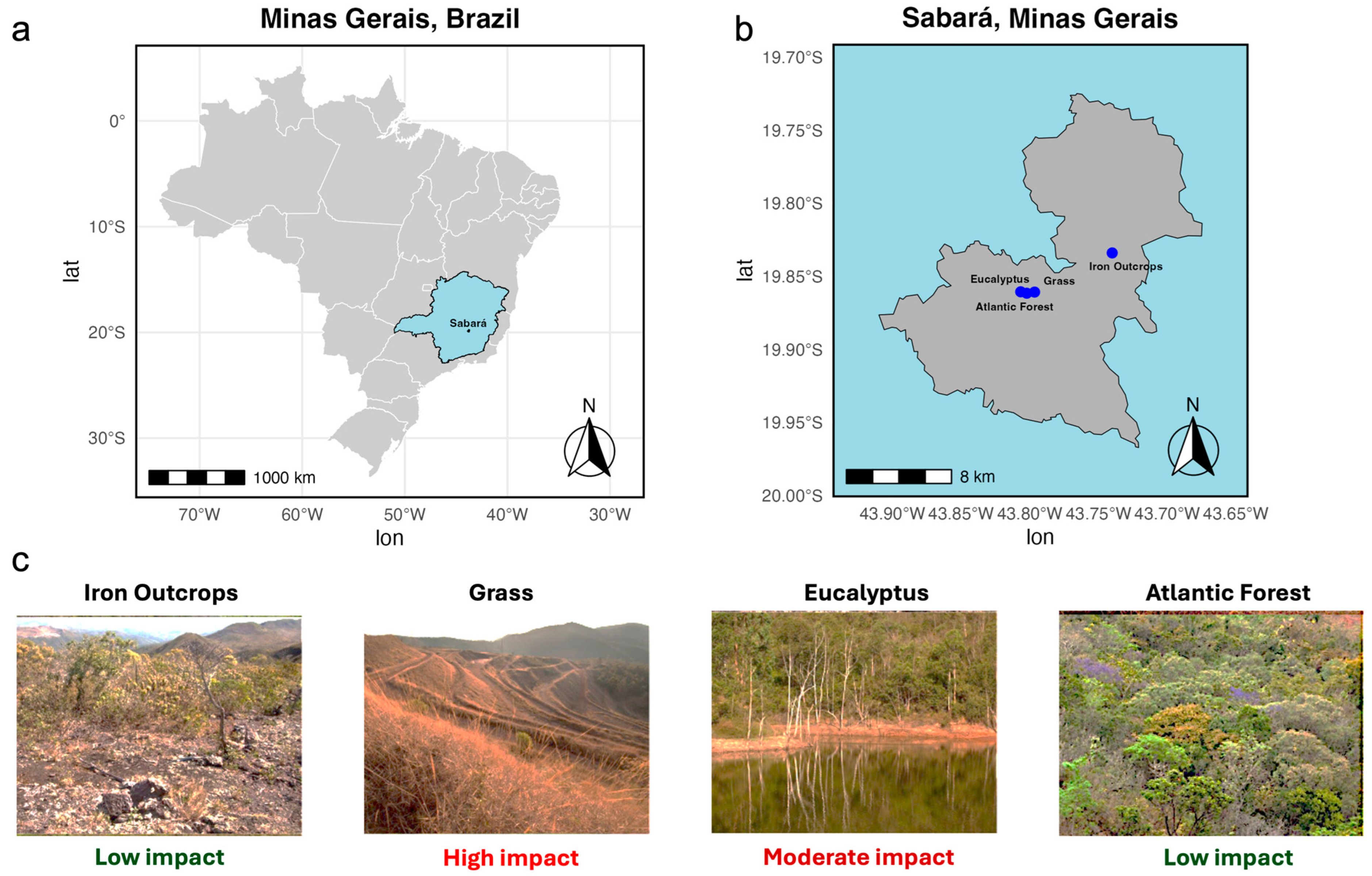

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Characterization of Fungal Communities

2.3. Functional Guild Analysis

2.4. Co-Occurrence Network Analysis

3. Results

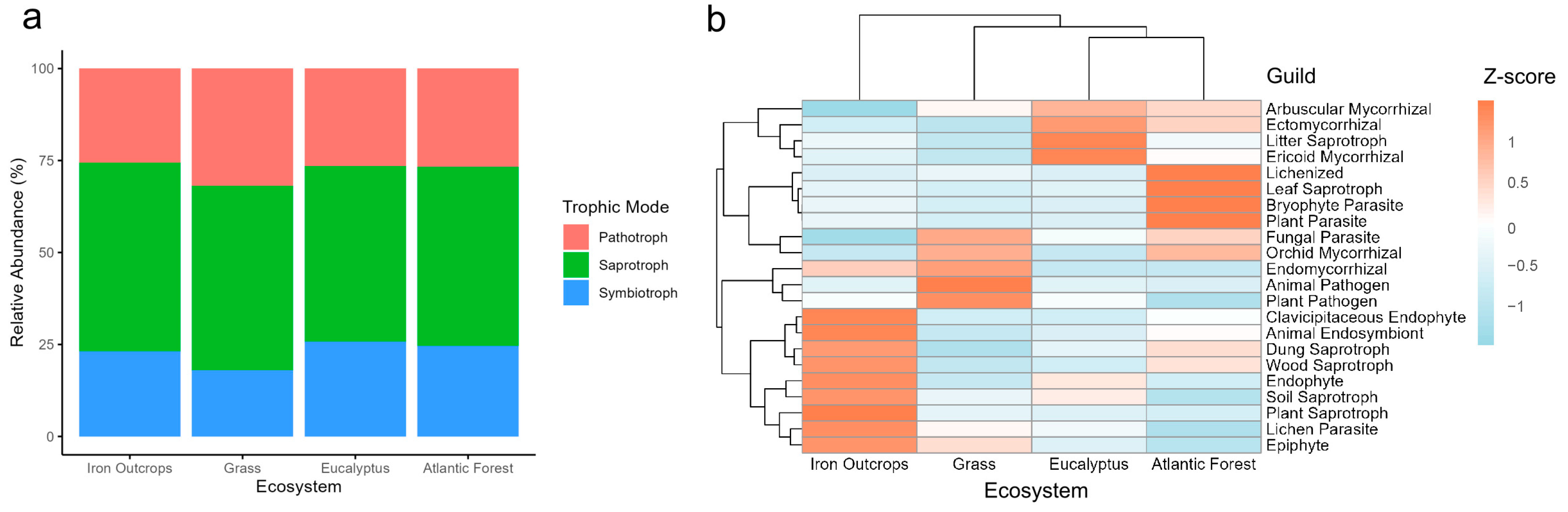

3.1. Distribution of Fungal Functional Guilds Across Ecosystems

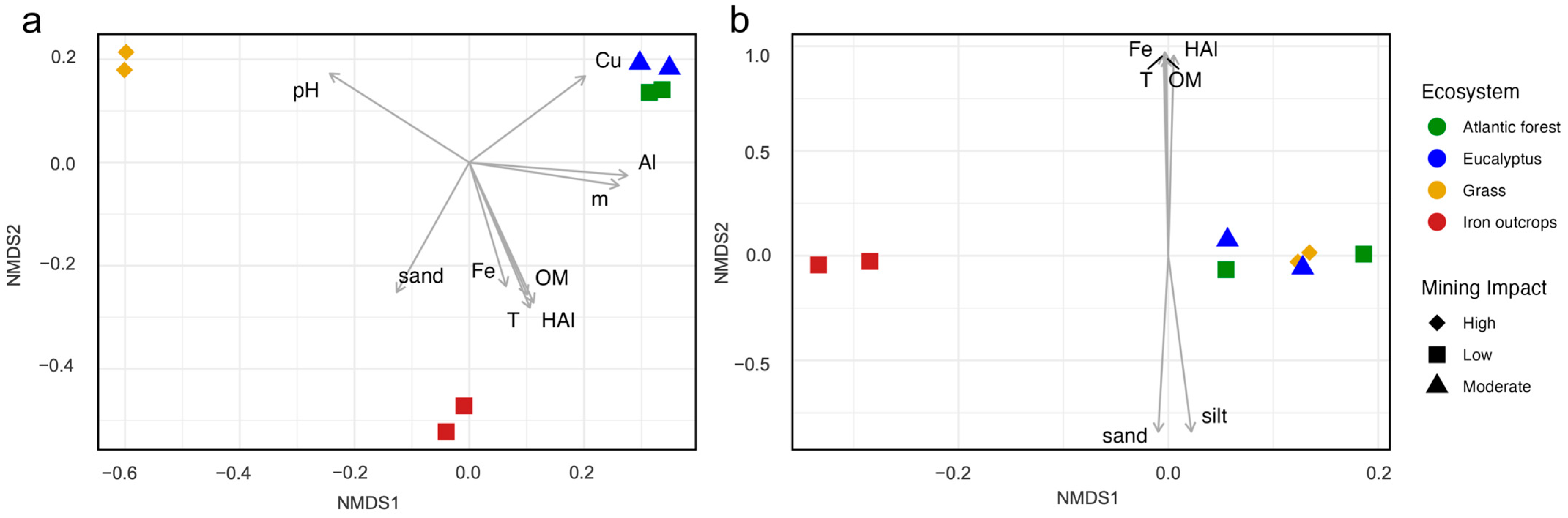

3.2. Influence of Soil Parameters on the Distribution of Fungal Functional Guilds Across Ecosystems

3.3. Co-Occurrence Network Across Ecosystems

4. Discussion

4.1. Profiling Functional Guilds in Unmined and Post-Mining Ecosystems

4.2. Correlations Between Soil Characteristics, Fungal Taxa, and Functional Guilds

4.3. Ecological Relationships Among Fungal Taxa: Co-Occurrence Network Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferreira, H.; Leite, M.G.P. A Life Cycle Assessment Study of Iron Ore Mining. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 1081–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yellishetty, M.; Ranjith, P.G.; Tharumarajah, A. Iron Ore and Steel Production Trends and Material Flows in the World: Is This Really Sustainable? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2010, 54, 1084–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, L. Brazil: Energy Policy. In Encyclopedia of Mineral and Energy Policy; Tiess, G., Majumder, T., Cameron, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 81–85. ISBN 978-3-662-47493-8. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, R.J.; Lu, Y.; Lu, L. Chapter 1—Introduction: Overview of the Global Iron Ore Industry. In Iron Ore, 2nd ed.; Lu, L., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Metals and Surface Engineering; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 1–56. ISBN 978-0-12-820226-5. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, I.F.; de, M. Figueirôa, S.F. 500 Years of Mining in Brazil: A Brief Review. Resour. Policy 2001, 27, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frouz, J. Chapter 6—Soil Recovery and Reclamation of Mined Lands. In Soils and Landscape Restoration; Stanturf, J.A., Callaham, M.A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 161–191. ISBN 978-0-12-813193-0. [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa, S.S.; Freitas, D.A.F.; Latini, A.O.; Silva, B.M.; Viana, J.H.M.; Campos, M.P.; Peixoto, D.S.; Botula, Y.-D. Iron Ore Mining Areas and Their Reclamation in Minas Gerais State, Brazil: Impacts on Soil Physical Properties. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frąc, M.; Hannula, S.E.; Bełka, M.; Jędryczka, M. Fungal Biodiversity and Their Role in Soil Health. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, E.B.; Júnior, P.P.; Veloso, T.G.R.; Jordão, T.C.; Kemmelmeier, K.; da Silva, M.C.S.; Pereira, E.G.; Kasuya, M.C.M. Mycobiota of Revegetated Post-Mining and Adjacent Unmined Sites 10 Years after Mining Decommissioning. Restor. Ecol. 2024, 32, e14253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngugi, M.R.; Fechner, N.; Neldner, V.J.; Dennis, P.G. Successional Dynamics of Soil Fungal Diversity along a Restoration Chronosequence Post-Coal Mining. Restor. Ecol. 2020, 28, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wu, S.; Liu, Y.; Yi, Q.; Hall, M.; Saha, N.; Wang, J.; Huang, Y.; Huang, L. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Regulate Plant Mineral Nutrient Uptake and Partitioning in Iron Ore Tailings Undergoing Eco-Engineered Pedogenesis. Pedosphere 2024, 34, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, E. Soil Microbiology, Ecology and Biochemistry; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-0-12-391411-8. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, D.L.; Hollingsworth, T.N.; McFarland, J.W.; Lennon, N.J.; Nusbaum, C.; Ruess, R.W. A First Comprehensive Census of Fungi in Soil Reveals Both Hyperdiversity and Fine-Scale Niche Partitioning. Ecol. Monogr. 2014, 84, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runnel, K.; Tedersoo, L.; Krah, F.-S.; Piepenbring, M.; Scheepens, J.F.; Hollert, H.; Johann, S.; Meyer, N.; Bässler, C. Toward Harnessing Biodiversity–Ecosystem Function Relationships in Fungi. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2024, 40, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Rengel, Z. Disentangling the Contributions of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi to Soil Multifunctionality. Pedosphere 2024, 34, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadd, G.M. Geomycology: Biogeochemical Transformations of Rocks, Minerals, Metals and Radionuclides by Fungi, Bioweathering and Bioremediation. Mycol. Res. 2007, 111, 3–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, L.; Buée, M.; Fauchery, L.; Lombard, V.; Barry, K.W.; Clum, A.; Copeland, A.; Daum, C.; Foster, B.; LaButti, K.; et al. Metatranscriptomics Sheds Light on the Links between the Functional Traits of Fungal Guilds and Ecological Processes in Forest Soil Ecosystems. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 1676–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Song, Z.; Bates, S.T.; Branco, S.; Tedersoo, L.; Menke, J.; Schilling, J.S.; Kennedy, P.G. FUNGuild: An Open Annotation Tool for Parsing Fungal Community Datasets by Ecological Guild. Fungal Ecol. 2016, 20, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Diao, L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Luo, Y.; An, S.; Cheng, X. Responses of Soil Fungal Communities and Functional Guilds to ~160 Years of Natural Revegetation in the Loess Plateau of China. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 967565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmelash, F.; Bekele, T.; Birhane, E. The Potential Role of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in the Restoration of Degraded Lands. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detheridge, A.P.; Comont, D.; Callaghan, T.M.; Bussell, J.; Brand, G.; Gwynn-Jones, D.; Scullion, J.; Griffith, G.W. Vegetation and Edaphic Factors Influence Rapid Establishment of Distinct Fungal Communities on Former Coal-Spoil Sites. Fungal Ecol. 2018, 33, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, G.A.M.; do Vale, H.M.M. Soil Yeast Communities in Revegetated Post-Mining and Adjacent Native Areas in Central Brazil. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, G.A.M.; Pires, E.C.C.; Barreto, C.C.; do Vale, H.M.M. Total Fungi and Yeast Distribution in Soils over Native and Modified Vegetation in Central Brazil. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Solo 2020, 44, e0200097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, G.A.M.; do Vale, H.M.M. Occurrence of Yeast Species in Soils under Native and Modified Vegetation in an Iron Mining Area. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Solo 2018, 42, e0170375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, C.K.; Marascalchi, M.N.; Rodrigues, A.V.; de Armas, R.D.; Stürmer, S.L. Morphological and Molecular Diversity of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Revegetated Iron-Mining Site Has the Same Magnitude of Adjacent Pristine Ecosystems. J. Environ. Sci. 2018, 67, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Handbook of Tropical Soil Biology: Sampling and Characterization of Below-Ground Biodiversity. Available online: https://www.routledge.com/A-Handbook-of-Tropical-Soil-Biology-Sampling-and-Characterization-of-Below-ground-Biodiversity/Moreira-Huising-Bignell/p/book/9781844075935 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Mašínová, T.; Bahnmann, B.D.; Větrovský, T.; Tomšovský, M.; Merunková, K.; Baldrian, P. Drivers of Yeast Community Composition in the Litter and Soil of a Temperate Forest. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2017, 93, fiw223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-Resolution Sample Inference from Illumina Amplicon Data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarenkov, K.; Nilsson, R.H.; Larsson, K.-H.; Taylor, A.F.S.; May, T.W.; Frøslev, T.G.; Pawlowska, J.; Lindahl, B.; Põldmaa, K.; Truong, C.; et al. The UNITE Database for Molecular Identification and Taxonomic Communication of Fungi and Other Eukaryotes: Sequences, Taxa and Classifications Reconsidered. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D791–D797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Cui, Y.; Li, X.; Yao, M. Microeco: An R Package for Data Mining in Microbial Community Ecology. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2021, 97, fiaa255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vegan: An R Package for Community Ecologists. Available online: https://vegandevs.github.io/vegan/ (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Kolde, R. Pheatmap: Pretty Heatmaps; CRAN: Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bastian, M.; Heymann, S.; Jacomy, M. Gephi: An Open Source Software for Exploring and Manipulating Networks. Proc. Int. AAAI Conf. Web Soc. Media 2009, 3, 361–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, J.L.; Morrissey, E.M.; Skousen, J.G.; Freedman, Z.B. Soil Microbial Succession Following Surface Mining Is Governed Primarily by Deterministic Factors. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2020, 96, fiaa114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Huang, J.; Zhu, X.; Chai, J.; Ji, X. Ecological Effects of Heavy Metal Pollution on Soil Microbial Community Structure and Diversity on Both Sides of a River around a Mining Area. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinhal-Freitas, I.C.; Corrêa, G.F.; Wendling, B.; Bobuľská, L.; Ferreira, A.S. Soil Textural Class Plays a Major Role in Evaluating the Effects of Land Use on Soil Quality Indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 74, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alteio, L.V.; Séneca, J.; Canarini, A.; Angel, R.; Jansa, J.; Guseva, K.; Kaiser, C.; Richter, A.; Schmidt, H. A Critical Perspective on Interpreting Amplicon Sequencing Data in Soil Ecological Research. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 160, 108357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Bahram, M.; Zinger, L.; Nilsson, R.H.; Kennedy, P.G.; Yang, T.; Anslan, S.; Mikryukov, V. Best Practices in Metabarcoding of Fungi: From Experimental Design to Results. Mol. Ecol. 2022, 31, 2769–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philippot, L.; Griffiths, B.S.; Langenheder, S. Microbial Community Resilience across Ecosystems and Multiple Disturbances. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2021, 85, e00026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liao, H.; Li, D.; Jing, Y. The Fungal Functional Guilds at the Early-Stage Restoration of Subalpine Forest Soils Disrupted by Highway Construction in Southwest China. Forests 2024, 15, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebreton, A.; Zeng, Q.; Miyauchi, S.; Kohler, A.; Dai, Y.-C.; Martin, F.M. Evolution of the Mode of Nutrition in Symbiotic and Saprotrophic Fungi in Forest Ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2021, 52, 385–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setälä, H.; McLean, M.A. Decomposition Rate of Organic Substrates in Relation to the Species Diversity of Soil Saprophytic Fungi. Oecologia 2004, 139, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Ramos, J.C.; Cale, J.A.; Cahill, J.F., Jr.; Simard, S.W.; Karst, J.; Erbilgin, N. Changes in Soil Fungal Community Composition Depend on Functional Group and Forest Disturbance Type. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 1105–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Bi, Y.; Cao, Y.; Peng, S.; Christie, P.; Ma, S.; Zhang, J.; Xie, L. Shifts in Composition and Function of Soil Fungal Communities and Edaphic Properties during the Reclamation Chronosequence of an Open-Cast Coal Mining Dump. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 767, 144465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Cao, H.; Zhao, P.; Wei, X.; Ding, G.; Gao, G.; Shi, M. Vegetation Restoration Alters Fungal Community Composition and Functional Groups in a Desert Ecosystem. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 589068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schappe, T.; Albornoz, F.E.; Turner, B.L.; Neat, A.; Condit, R.; Jones, F.A. The Role of Soil Chemistry and Plant Neighbourhoods in Structuring Fungal Communities in Three Panamanian Rainforests. J. Ecol. 2017, 105, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, E.B.; Duguid, M.C.; Kuebbing, S.E.; Lendemer, J.C.; Bradford, M.A. The Functional Role of Ericoid Mycorrhizal Plants and Fungi on Carbon and Nitrogen Dynamics in Forests. New Phytol. 2022, 235, 1701–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottke, I.; Haug, I.; Setaro, S.; Suárez, J.P.; Weiß, M.; Preußing, M.; Nebel, M.; Oberwinkler, F. Guilds of Mycorrhizal Fungi and Their Relation to Trees, Ericads, Orchids and Liverworts in a Neotropical Mountain Rain Forest. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2008, 9, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrocco, S. Dung-Inhabiting Fungi: A Potential Reservoir of Novel Secondary Metabolites for the Control of Plant Pathogens. Pest Manag. Sci. 2016, 72, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bills, G.F.; Gloer, J.B. Biologically Active Secondary Metabolites from the Fungi. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4, 10–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kües, U. Fungal Enzymes for Environmental Management. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jia, Z.; Sun, Q.; Zhan, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, D. Ecological Restoration Alters Microbial Communities in Mine Tailings Profiles. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zine, H.; Hakkou, R.; Papazoglou, E.G.; Elmansour, A.; Abrar, F.; Benzaazoua, M. Revegetation and Ecosystem Reclamation of Post-Mined Land: Toward Sustainable Mining. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 21, 9775–9798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobi, C.M.; do Carmo, F.F. The Contribution of Ironstone Outcrops to Plant Diversity in the Iron Quadrangle, a Threatened Brazilian Landscape. Ambio 2008, 37, 324–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes-Filho, E.I.; Reynaud Schaefer, C.E.G.; Faria, R.M.; Lopes, A.; Francelino, M.R.; Gomes, L.C. The Unique and Endangered Campo Rupestre Vegetation and Protected Areas in the Iron Quadrangle, Minas Gerais, Brazil. J. Nat. Conserv. 2022, 66, 126131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Wang, Y.; Ye, S.; Liu, S.; Stirling, E.; Gilbert, J.A.; Faust, K.; Knight, R.; Jansson, J.K.; Cardona, C.; et al. Earth Microbial Co-Occurrence Network Reveals Interconnection Pattern across Microbiomes. Microbiome 2020, 8, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guseva, K.; Darcy, S.; Simon, E.; Alteio, L.V.; Montesinos-Navarro, A.; Kaiser, C. From Diversity to Complexity: Microbial Networks in Soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 169, 108604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Sun, X.; Li, S.; Zhou, W.; Yu, J.; Zhao, G. Biogeographic and Co-Occurrence Network Differentiation of Fungal Communities in Warm-Temperate Montane Soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 948, 174911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Yang, Z.; He, K.; Zhou, W.; Feng, W. Soil Fungal Community Diversity, Co-Occurrence Networks, and Assembly Processes under Diverse Forest Ecosystems. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challacombe, J.F.; Hesse, C.N.; Bramer, L.M.; McCue, L.A.; Lipton, M.; Purvine, S.; Nicora, C.; Gallegos-Graves, L.V.; Porras-Alfaro, A.; Kuske, C.R. Genomes and Secretomes of Ascomycota Fungi Reveal Diverse Functions in Plant Biomass Decomposition and Pathogenesis. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mali, T.; Kuuskeri, J.; Shah, F.; Lundell, T.K. Interactions Affect Hyphal Growth and Enzyme Profiles in Combinations of Coniferous Wood-Decaying Fungi of Agaricomycetes. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthony, M.A.; Crowther, T.W.; van der Linde, S.; Suz, L.M.; Bidartondo, M.I.; Cox, F.; Schaub, M.; Rautio, P.; Ferretti, M.; Vesterdal, L.; et al. Forest Tree Growth Is Linked to Mycorrhizal Fungal Composition and Function across Europe. ISME J. 2022, 16, 1327–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Sun, H.; Yang, W.; Xu, H. The Response Patterns of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal and Ectomycorrhizal Symbionts Under Elevated CO2: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goberna, M.; Verdú, M. Cautionary Notes on the Use of Co-Occurrence Networks in Soil Ecology. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 166, 108534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierer, N.; Nemergut, D.; Knight, R.; Craine, J.M. Changes through Time: Integrating Microorganisms into the Study of Succession. Res. Microbiol. 2010, 161, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ecosystem | Impact Level | Ecosystem Attributes | Diversity Metrics | Dominant Taxa (>1% at Genus level) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shannon | Simpson | Richness | ||||

| Atlantic Forest | Low | Semi-deciduous seasonal forest region. Originally belonging to the Atlantic forest biome. Currently defined by secondary vegetation in different stages of natural regeneration. | 5.14 ± 0.02 | 0.98 ± 0.001 | 199 ± 10.6 | Penicillium, Saitozyma, Leohumicola, Talaromyces, Metarhizium, Trichoderma, Calonectria, Amanita |

| Iron Outcrops | Low | Preserved rock environment. Vegetation on ferruginous substrates where the dominance of Cactaceae and grasses represents the local physiognomy. | 4.82 ± 0.02 | 0.97 ± 0.001 | 194 ± 4.24 | Penicillium, Talaromyces, Umbelopsis, Aspergillus, Saitozyma, Tolypocladium, Cladosporium |

| Eucalyptus | Moderate | Reforested environments since 2006. Originally belonging to the Atlantic forest biome. Homogeneous plantations of Eucalyptus spp. at different ages occupy extensive surfaces to remediate the impacts of the mining activity. | 4.61 ± 0.009 | 0.96 ± 0.001 | 196 ± 5.65 | Saitozyma, Sagenomella, Penicillium, Oidiodendron, Chloridium, Talaromyces, Leohumicola, Trichoderma, Laccaria |

| Grass | High | Sterile/tailings piles and slopes. Originally belonging to the Atlantic forest biome. The ongoing environmental rehabilitation process started in 2006 after the mining activity ended. Currently, the soil is covered with grass, mostly Melinis minutiflora. | 5.40 ± 0.01 | 0.99 ± 0.001 | 232 ± 0.001 | Penicillium, Aspergillus, Fusarium, Coniosporium, Mycosymbioces, Trechispora, Periconia, Cladosporium, Knufia |

| FUNGuild Classifications | Relative Abundance (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iron Outcrops | Grass | Eucalyptus | Atlantic Forest | |

| Trophic mode | ||||

| Saprotroph | 51.33 | 50.16 | 47.72 | 48.69 |

| Pathotroph | 25.56 | 31.83 | 26.52 | 26.70 |

| Symbiotroph | 23.11 | 18.01 | 25.76 | 24.61 |

| Functional guild | ||||

| Bryophyte parasite | 3.27 | 2.74 | 2.25 | 7.48 |

| Dung saprotroph | 9.83 | 6.64 | 7.65 | 8.72 |

| Ectomycorrhizal | 4.94 | 4.11 | 9.73 | 8.07 |

| Fungal parasite | 9.97 | 14.58 | 12.28 | 13.61 |

| Leaf saprotroph | 1.88 | 1.58 | 1.86 | 4.16 |

| Plant parasite | 1.88 | 1.58 | 1.63 | 3.91 |

| Wood saprotroph | 17.12 | 14.49 | 14.83 | 16.06 |

| Animal pathogen | 11.06 | 17.29 | 11.00 | 10.60 |

| Endophyte | 10.89 | 8.21 | 9.62 | 8.39 |

| Plant pathogen | 12.38 | 16.67 | 12.40 | 9.05 |

| Lichen parasite | 2.57 | 2.27 | 2.20 | 1.95 |

| Litter saprotroph | 0.96 | 0.61 | 1.86 | 0.98 |

| Soil saprotroph | 4.90 | 3.57 | 4.05 | 2.93 |

| Plant saprotroph | 2.99 | 1.48 | 1.39 | 1.30 |

| Epiphyte | 3.39 | 2.71 | 1.97 | 1.55 |

| Lichenized | 0.45 | 0.53 | 0.46 | 1.06 |

| Arbuscular mycorrhizal | 0.56 | 1.04 | 1.27 | 1.14 |

| Endomycorrhizal | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0 | 0 |

| Ericoid mycorrhizal | 1.09 | 0.35 | 4.05 | 1.88 |

| Orchid mycorrhizal | 0 | 0.35 | 0 | 0.32 |

| Clavicipitaceous endophyte | 0.75 | 0 | 0 | 0.25 |

| Animal endosymbiont | 0.29 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.17 |

| Soil Parameters 1 | Iron Outcrops | Grass | Eucalyptus | Atlantic Forest | Fungal Taxa | Fungal Guild | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-Value 2 | R2 | p-Value2 | R2 | |||||

| pH | 4.5 ± 0.48 | 5.95 ± 0.12 | 4.72 ± 0.05 | 4.65 ± 0.1 | 0.004 ** | 0.98 | 0.203 | 0.45 |

| Al3+ (cmolc dm−3) | 1.55 ± 0.73 | 0.1 ± 0.001 | 2.6 ± 0.65 | 1.75 ± 0.45 | 0.017 * | 0.84 | 0.168 | 0.49 |

| H + Al (cmolc dm−3) | 22.54 ± 11.43 | 1.49 ±0.13 | 12.17 ± 2.66 | 9.86 ± 0.89 | 0.006 ** | 0.95 | 0.001 *** | 0.91 |

| T (cmolc dm−3) | 23.61 ± 11.73 | 3.15 ± 1.08 | 12.54 ± 2.77 | 11.03 ± 0.98 | 0.006 ** | 0.95 | 0.002 ** | 0.92 |

| m (%) | 57.86 ± 18.49 | 7.42 ± 4.18 | 87.51 ± 2.49 | 60.69 ± 17.5 | 0.037 * | 0.78 | 0.245 | 0.41 |

| OM (g kg−1) | 95.7 ± 34.4 | 13.2 ± 2.53 | 50.9 ± 2.35 | 47.7 ± 10.9 | 0.004 ** | 0.90 | 0.002 ** | 0.90 |

| Fe (mg dm−3) | 236.71 ± 199.62 | 43.32 ± 15.56 | 122.66 ± 62.77 | 94.5 ± 26.46 | 0.023 * | 0.73 | 0.001 *** | 0.93 |

| Cu (mg dm−3) | 0.69 ± 0.51 | 0.73 ± 0.62 | 2.76 ± 0.58 | 3.02 ± 1.35 | 0.030 * | 0.83 | 0.226 | 0.45 |

| Sand (g kg−1) | 62 ± 8.75 | 46.75 ± 6.99 | 30.25 ± 11.52 | 27.25 ± 8.3 | 0.006 ** | 0.88 | 0.044 * | 0.71 |

| Silt (g kg−1) | 17.5 ± 7.04 | 32.75 ± 7.88 | 34 ± 5.47 | 42.25 ± 4.03 | 0.080 | 0.68 | 0.046 * | 0.72 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moreira, G.; dos Reis, J.B.A.; Pires, E.C.C.; Barreto, C.C.; do Vale, H.M.M. Fungal Guilds Reveal Ecological Redundancy in a Post-Mining Environment. Mining 2025, 5, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/mining5020028

Moreira G, dos Reis JBA, Pires ECC, Barreto CC, do Vale HMM. Fungal Guilds Reveal Ecological Redundancy in a Post-Mining Environment. Mining. 2025; 5(2):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/mining5020028

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoreira, Geisianny, Jefferson Brendon Almeida dos Reis, Elisa Catão Caldeira Pires, Cristine Chaves Barreto, and Helson Mario Martins do Vale. 2025. "Fungal Guilds Reveal Ecological Redundancy in a Post-Mining Environment" Mining 5, no. 2: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/mining5020028

APA StyleMoreira, G., dos Reis, J. B. A., Pires, E. C. C., Barreto, C. C., & do Vale, H. M. M. (2025). Fungal Guilds Reveal Ecological Redundancy in a Post-Mining Environment. Mining, 5(2), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/mining5020028