1. Introduction

In 1977, Richard Nelson published

The Moon and the Ghetto, a work that articulated a paradox that remains strikingly relevant today for

platformization [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]: why can a society capable of achieving the most spectacular technical feats, such as sending humans to the Moon, fail to address persistent problems of social inequality and poverty in its own urban ghettos? Nelson revisited this paradox in 2011 [

9], underscoring its enduring resonance in debates about the limits of innovation. His concern was not only with technological capacity but with the institutional and political conditions that determine how innovation is mobilized, for whom, and to what ends. The paradox has since been adopted across the social sciences and political economy as a shorthand for the asymmetries between scientific–technical advancement and the stubborn persistence of social exclusion [

10]. Nelson’s metaphor provides a critical lens for interrogating

Web3 platformization [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]: a sociotechnical assemblage encompassing blockchain, decentralized finance, distributed ledgers, and artificial intelligence (AI) [

17]. These infrastructures showcase remarkable technical ingenuity, but they also reproduce old inequities in new guises [

18,

19].

The

Web3 ecosystem has been hailed by its proponents as the dawn of a more democratic internet [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. By distributing power away from centralized intermediaries, it promises to empower users, communities, and nations to reclaim control over digital infrastructures. Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs), tokenized governance systems, and blockchain-based cooperatives are presented as evidence of a shift toward openness and collective self-determination [

26,

27,

28]. Yet critical scholarship and growing empirical evidence tell a more ambivalent story [

29,

30,

31,

32]. Far from dismantling monopolies, Web3 has generated new forms of concentration and exclusion, raising questions about whether decentralization equates to democratization [

33]. As the author’s own Fulbright-funded action research fieldwork in Silicon Valley between 2022 and 2025 demonstrates, participation in DAOs is often limited to a small subset of technically literate, capital-rich actors [

34,

35]. A handful of token holders frequently dominate governance decisions, while wider communities remain excluded from meaningful influence. Technical literacy, social networks, and financial capacity transform early adopters into new gatekeepers [

36]. The surface appearance of decentralization can thus mask a deeper entrenchment of power.

The growing body of critical literature on

Web3 underscores this disjunction. Scholars such as David Golumbia [

37] and Kevin A. Carson [

38] have exposed the ideological underpinnings of

cyberlibertarianism, a worldview that prioritizes individual sovereignty, market freedom, and technical autonomy while neglecting solidarity, accountability, and justice. Studies of blockchain governance [

26,

31] reveal how tokenized systems, despite their rhetoric of openness, often function oligarchically in practice. Quinn DuPont [

13] argues that Web3’s emancipatory potential can only be realized if it evolves into a form of digital polycentric governance that embeds participation at multiple levels. Kelsie Nabben’s recent article reframes data value as relational rather than intrinsic, underscoring that decentralization alone is insufficient [

6]. Accountability, she argues, alongside Masso et al. [

39] and Kitchin et al. [

40], must be designed into the system, involving contributors directly in decision-making and ensuring that data value creation is aligned with democratic principles. These critiques converge on a common point: without accountability, solidarity, and inclusive governance, decentralization risks becoming an illusion [

41].

Despite the growing body of critical work on Web3, three gaps persist. First, critiques of cyberlibertarianism and elite capture [

37,

38] have not been systematically connected to the institutional analysis of innovation systems. Second, empirical studies documenting participation asymmetries and token-based oligarchies [

6,

13] often lack a comparative framework that spans Global North and South contexts. Third, while recent scholarship calls for accountability and social embedding in decentralized governance [

39,

40], few studies explain how such embedding could be operationalized through mission-oriented innovation systems. This article addresses these gaps by integrating innovation systems theory with critical Web3 governance research to propose a framework for evaluating decentralization not only as a technical property but as a condition for democratic resilience.

This article builds on and extends these insights by reframing

Web3 platformization through the lens of innovation systems. Innovation systems theory, as articulated by scholars such as Christopher Freeman [

42], Bengt-Åke Lundvall [

43], Nelson himself [

7], and more recently Mariana [

44], emphasizes that technological outcomes are embedded in wider institutional, social, and political contexts. Innovation is not simply the product of technical ingenuity, but of networks of actors, policy frameworks, financial infrastructures, and cultural imaginaries. From this perspective, Web3 should not be understood merely as a decentralized technical infrastructure, but as an emerging innovation system whose directionality, inclusivity, and legitimacy depend on the governance models it adopts [

12]. Situating Web3 in this theoretical framework allows us to interrogate not only whether it decentralizes but whether it democratizes—and to evaluate success by criteria of accountability, inclusivity, and worker empowerment rather than by metrics of token distribution or technical sophistication.

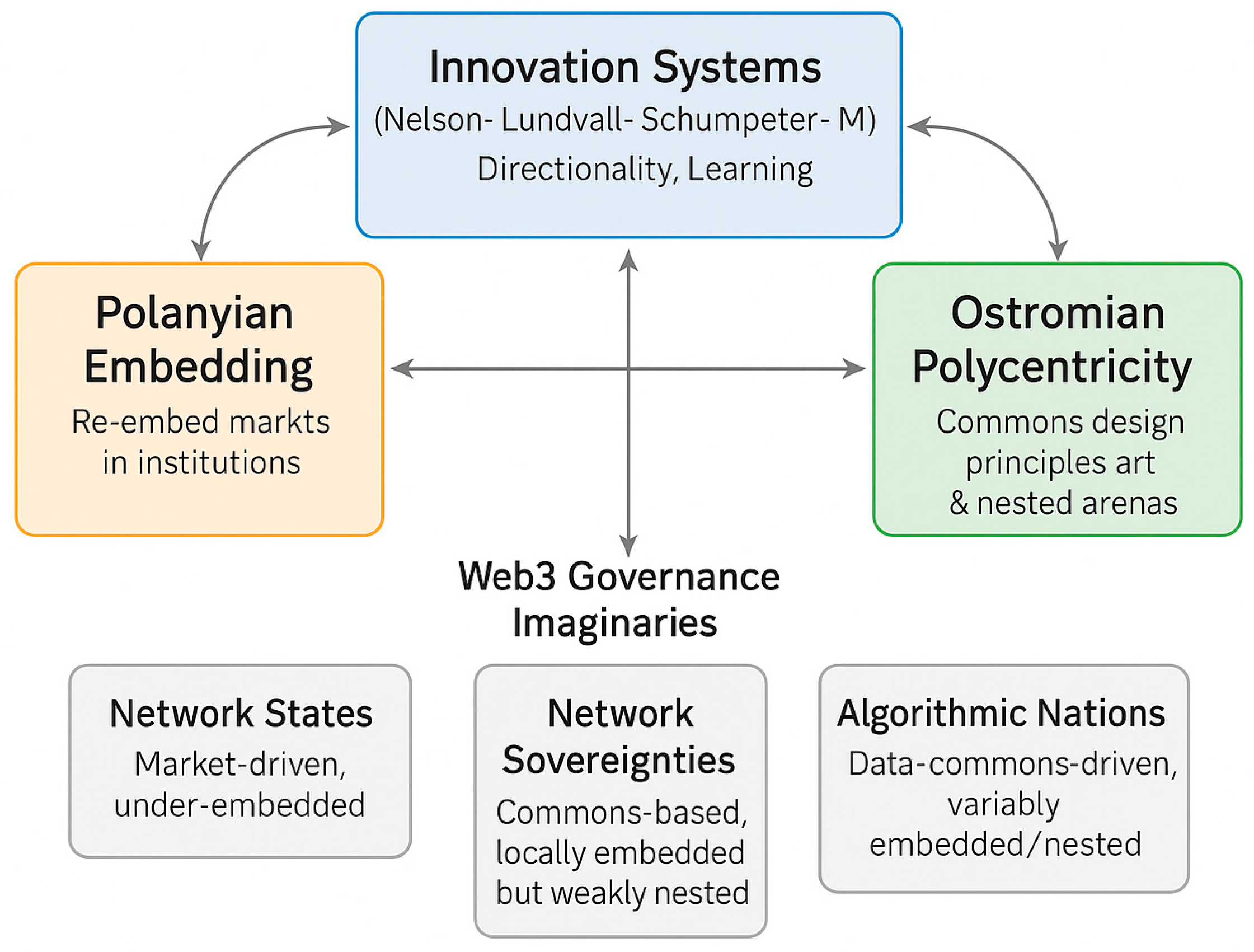

Adopting an innovation systems perspective also brings into focus the competing

governance imaginaries that circulate within Web3 discourse. Drawing on the author’s earlier work [

12], this article identifies three paradigms of post-Westphalian digital sovereignty that are playing out in parallel [

45,

46,

47]. The first,

Network States, advances a crypto-libertarian model in which sovereignty is reimagined as market-driven and exclusionary, privileging those with financial and technical capital [

48]. The second,

Network Sovereignties, foregrounds cooperative participation and commons-based governance, but risks reproducing centralized, state-like logics even while claiming to decentralize [

26]. The third,

Algorithmic Nations, proposes emancipatory governance rooted in cultural specificity, data commons, and city-regional coordination [

34]. Yet even in this paradigm, the digitally excluded remain trapped in new ghettos, unable to participate in the supposed benefits of algorithmic governance. These imaginaries illustrate both the promise and the limitations of Web3: they demonstrate how sovereignty itself is being reconfigured while also revealing the persistence of inequality.

The persistence of “platform ghettos” thus calls for a reconsideration of how Web3 infrastructures are designed, governed, and evaluated. Digital exclusion, precarious labor, and inequitable data governance are not peripheral issues but central features of how platform economies operate. Addressing them requires moving beyond the rhetoric of decentralization toward the construction of

hybrid governance models. Data cooperatives and trusts can align law and code to ensure that contributors retain agency over their data. Federated platforms can empower communities without reintroducing centralized extraction [

4]. Governance systems that combine cooperative traditions with decentralized infrastructures can embed solidarity and accountability in technical design [

13]. These hybrid models resonate with Mazzucato’s call for

mission-oriented innovation systems that prioritize public value and social goals alongside technical achievement.

Against this backdrop, the research question animating this article is straightforward but urgent:

How can innovation systems theory help us evaluate whether Web3 platformization contributes to democratizing digital infrastructures, rather than reproducing new forms of exclusion and elite capture? To answer this, the article integrates conceptual analysis with empirical insights drawn from multi-sited action research. During the author’s Fulbright period, he observed and participated in debates within the Silicon Valley ecosystem, attended workshops organized by BlockchainGov ERC, and engaged with initiatives ranging from DAOs in the Global North to mobile-based crypto solutions in the Global South [

49,

50,

51]. These experiences revealed stark asymmetries between contexts: while well-funded DAOs struggled with participation deficits, grassroots projects in Kenya and Latin America confronted infrastructural barriers that limited access to even the most basic functionalities. The contrast underscores that the problem of the “platform ghetto” is not merely metaphorical but grounded in lived realities.

The contribution of this article is threefold. Theoretically, it extends innovation systems scholarship into the domain of Web3, offering a framework for evaluating digital infrastructures not only by their decentralization but by their democratic resilience. Empirically, it draws on comparative cases from both the Global North and South, highlighting the uneven geographies of Web3 adoption and governance. Conceptually, it revisits and refines the notion of post-Westphalian digital sovereignties, situating Web3 within broader debates on platform governance, political economy, and digital citizenship. In doing so, the article directly responds to recent criticisms that discussions of decentralization have become overfamiliar and insufficiently critical by explicitly integrating innovation systems theory with critiques of cyberlibertarianism, elite capture, and accountability deficits. This combined approach demonstrates that Web3 must be analyzed not only as a technical infrastructure but as a contested innovation system whose democratic legitimacy depends on institutional embedding, solidarity, and cooperative safeguards.

The stakes of this debate are high. If Web3 infrastructures continue to prioritize technical experimentation over accountability and solidarity, they risk entrenching new forms of aristocracy under the guise of openness. If, however, they can be reconfigured as inclusive innovation systems, they may offer pathways toward more equitable digital economies. Nelson’s metaphor reminds us that technological capability is not synonymous with social progress. Just as reaching the Moon did not resolve the problems of the ghetto, building distributed ledgers does not, by itself, guarantee empowerment. The challenge for scholars, policymakers, and practitioners is to ensure that innovation systems are oriented toward justice, accountability, and solidarity. This article takes up that challenge by interrogating Web3 platformization through Nelson’s paradox, offering a critical account of its promises, pitfalls, and possibilities for reimagining digital governance as a

commons [

52,

53].

This article moves beyond familiar critiques of decentralization by reframing Web3 platformization through the lens of innovation systems. Drawing on ethnographic fieldwork in Silicon Valley and comparative Global North/South cases, it demonstrates how governance imaginaries (Network States, Network Sovereignties, Algorithmic Nations) reproduce exclusion and proposes hybrid innovation systems as pathways toward accountability, solidarity, and democratic resilience.

The article is structured as follows. The next section revisits innovation systems theory, drawing on Nelson, Lundvall, Freeman, Schumpeter, and Mazzucato to establish a framework for analyzing Web3 beyond technical decentralization. The third section details the methodology and empirical basis of the study, grounded in multi-sited action research conducted during the author’s Fulbright period in Silicon Valley and comparative case studies across the Global North and South. The fourth section presents findings on the illusion of decentralization, analyzing empirical evidence of oligarchic tendencies in DAOs and token governance and situating them within three governance imaginaries—Network States, Network Sovereignties, and Algorithmic Nations. Finally, the conclusion turns to policy and governance implications, outlining hybrid innovation systems that align law with code, embed accountability, and institutionalize solidarity through data cooperatives and federated infrastructures. It also revisits Nelson’s paradox to assess the stakes of Web3 platformization for democratic resilience, highlighting pathways for reorienting decentralized infrastructures toward inclusive innovation systems.

Building on Nelson’s Moon and the Ghetto paradox, this article hypothesizes that Web3 decentralization reproduces existing inequalities unless it is institutionally embedded and polycentrically nested within inclusive innovation systems. In other words, technological decentralization alone is insufficient to generate democratic outcomes; without mechanisms for accountability, capability formation, and social protection, token-based governance will tend to concentrate power among technically skilled or capital-rich actors. Conversely, where decentralized infrastructures are complemented by cooperative, federated, or mission-oriented institutions, they are more likely to produce democratic resilience. This hypothesis guides the comparative analysis of Global North and South cases presented in the following sections.

2. Literature Review: Innovation Systems and the Promise of Web3

Innovation systems theory has long emphasized that technological change cannot be understood in isolation from its institutional, social, and political contexts [

42]. From Joseph Schumpeter’s early twentieth-century accounts of “creative destruction” to Richard Nelson’s comparative studies of national innovation systems and Bengt-Åke Lundvall’s elaboration of interactive learning, the central insight is clear [

7,

43,

54]: innovation is never a purely technical phenomenon but a systemic process shaped by interactions among firms, states, users, financial institutions, and wider societal frameworks. Mariana Mazzucato has more recently revitalized this tradition by highlighting the role of the state as an entrepreneurial actor capable of shaping and directing innovation toward socially desirable missions [

44].

Web3, frequently described by its advocates as the “next internet,” offers a compelling test case for revisiting these theories. Its proponents herald it as a radical break with the centralized, corporate-dominated Web 2.0 model, claiming that by distributing control across distributed ledgers and cryptographic infrastructures, Web3 can empower individuals and communities. The vision is not merely technical but ideological: a promise of disintermediation, transparency, and autonomy in the face of entrenched platform monopolies.

Yet when examined through the lens of innovation systems, Web3 appears less as a disruptive revolution and more as a contested field in which familiar dynamics of concentration, exclusion, and capture are playing out under new guises. Schumpeter’s concept of “creative destruction” is useful here [

54]: Web3 does indeed disrupt incumbent business models, from banking to social media, but it also creates new monopolistic tendencies, with early adopters and venture-capital-backed actors consolidating disproportionate influence [

51]. Nelson’s comparative work on innovation systems highlighted how institutional diversity leads to divergent outcomes; in the Web3 ecosystem, institutional frameworks remain underdeveloped, leaving technical elites and speculative markets to set the terms of governance. Lundvall’s emphasis on learning and interaction points to another gap: effective innovation requires broad-based participation, yet Web3 participation is often restricted by technical literacy, financial capacity, and cultural capital [

12].

A Polanyian–Ostromian lens reframes innovation systems as

institutionally embedded and

collectively governed processes rather than technical artifacts. For Karl Polanyi, markets are never self-regulating [

36]: economic activity is

embedded in social and political institutions, and attempts to “disembed” it provoke a

double movement—counter-pressures demanding social protection against commodification, especially of labor, land, and money. The Polanyian question for Web3, then, is not

how decentralized a protocol is, but

how it is re-embedded in legal norms, democratic oversight, and social rights [

21,

31].

Elinor Ostrom complements this with a pragmatic grammar of

governing shared resources. Her work shows that communities can steward commons sustainably when design principles—clearly defined boundaries, participatory rule-making, monitoring, graduated sanctions, conflict-resolution arenas, and

nested (

polycentric)

governance—are in place [

52,

53]. Transposed to Web3, this implies that DAOs, data cooperatives, and federated platforms require more than code: they need

credible membership,

fit-for-purpose rules,

transparent monitoring, and

polycentric architectures that align local autonomy with broader coordination. In short, Ostrom turns “decentralization” from a technological slogan into a

testable institutional design problem.

This Polanyi–Ostrom synthesis sharpens the innovation systems tradition. Classic accounts—from Schumpeter’s “creative destruction” to Nelson’s and Lundvall’s comparative and interactive learning perspectives—already insist that innovation outcomes hinge on institutions, capabilities, and social learning [

7,

43,

54]. Mazzucato’s mission-oriented approach adds that public actors can shape directionality toward social goals [

44]. But

Polanyi specifies the stakes (preventing disembedding and elite capture), while

Ostrom supplies the toolkit (design principles and polycentricity) for making decentralized infrastructures

actually democratic. Seen this way, Web3 is not a revolution that makes institutions obsolete; it is a

stress test of institutional embedding: who sets the rules, who monitors, who can contest, and at what scale?

Applying this perspective to Web3 reveals why familiar patterns of

concentration, exclusion,

and capture recur. Without Polanyian re-embedding (labor protections, due process, public value) and Ostromian design (clear boundaries, participatory rule-making, nested oversight), token systems default to

wealth-weighted control, participation drops, and “trustless” architectures mask new gatekeepers. Conversely, when

data cooperatives and

federated infrastructures incorporate Ostrom’s principles within mission-oriented innovation policies, decentralization can be coupled to

accountability, inclusion, and solidarity rather than speculation. In short, the promise of Web3 does not hinge on distributing ledgers but on

embedding them in the kinds of institutional arrangements Polanyi and Ostrom showed are necessary for social justice and sustainable governance [

7,

36,

43,

44,

52,

53].

Garrett Hardin’s influential metaphor of

the tragedy of the commons casts a long shadow over debates on collective governance [

35]. His claim that shared resources inevitably collapse under the weight of individual self-interest has often been mobilized—explicitly or implicitly—by Web3 advocates to justify “trustless” architectures in which algorithmic enforcement substitutes for social institutions. Yet, as Ostrom persuasively demonstrated, Hardin mistook a design problem for a universal law [

52,

53]: commons do not fail because they are shared, but because they lack inclusive governance principles. The persistence of Hardin’s pessimism in Web3 discourse risks foreclosing cooperative alternatives just as real-world challenges demand them. In contrast, visions such as Bastani’s

Fully Automated Luxury Communism imagine a horizon where digital infrastructures enable abundance and emancipation; but without resolving the institutional preconditions for equitable distribution, these remain utopian provocations rather than actionable designs [

55]. The task for innovation systems theory, then, is not to oscillate between Hardin’s dystopian inevitability and Bastani’s utopian excess, but to operationalize institutional architectures—what Mazzucato terms mission-oriented systems—that can channel technical ingenuity toward public value, embedding solidarity and justice into the infrastructures of the digital economy [

44].

Mazzucato’s contribution is particularly salient. Her concept of mission-oriented innovation underscores that innovation must be directed toward addressing societal challenges such as climate change, inequality, or public health. By contrast, much of Web3 innovation remains oriented toward speculative financial returns and libertarian ideals of sovereignty. Venture capital funding structures incentivize rapid scaling and token appreciation, not social value. The contrast is stark: while governments in the twentieth century directed innovation toward collective missions such as space exploration or health care, Web3’s current trajectory is largely defined by market speculation, meme-driven finance, and the pursuit of private gain. The challenge, therefore, is not only technical but systemic: how can Web3 infrastructures be reoriented as part of innovation systems that prioritize accountability, inclusivity, and public value?

Situating Web3 within broader debates on platform economies highlights the stakes of this question. The platform economy has been widely analyzed as a new mode of capitalist accumulation, in which value is extracted from data flows, user labor, and network effects [

56,

57]. Platforms such as Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Uber dominate not by producing goods but by orchestrating ecosystems of interaction, monetizing access, and locking in users through economies of scale. Critical scholars have emphasized the asymmetries of power that result, whereby platforms act as private regulators of markets, labor, and information. Web3 is often positioned as the antidote to these dynamics: an infrastructure that disperses control, eliminates gatekeepers, and enables peer-to-peer coordination [

11].

However, this narrative risks reproducing what David Golumbia calls the myth of

cyberlibertarianism [

37]. By assuming that technical decentralization automatically leads to political or economic decentralization, Web3 discourse obscures the systemic inequalities that shape who participates, who benefits, and who governs. Early adopters with the resources to mine or purchase tokens at favorable rates often accumulate disproportionate wealth and voting power. DAOs ostensibly designed for collective governance frequently operate with extremely low participation rates, with decision-making concentrated among a few active insiders. Technical expertise becomes a form of gatekeeping, excluding those without advanced knowledge of cryptography, coding, or tokenomics. Far from dissolving hierarchies, Web3 may entrench them in algorithmic and financial forms that are less visible but no less powerful.

The language of sovereignty further illuminates these tensions [

45]. In an era when platforms operate across borders and states struggle to regulate digital infrastructures, questions of sovereignty are increasingly articulated in post-Westphalian terms. Web3 introduces novel imaginaries of sovereignty that align with different ideological traditions [

12]. The vision of

Network States articulated by Balaji Srinivasan reflects a radical libertarian reimagining of sovereignty, where digital-first communities with shared financial infrastructures claim quasi-statehood [

48]. By contrast, the idea of

Network Sovereignties emphasizes collective governance and commons-based approaches, seeking to embed cooperative principles into platform design [

26,

34,

52,

53]. A third vision,

Algorithmic Nations, imagines sovereignty rooted in cultural and territorial specificities, mediated through data commons and city-regional coordination [

29]. Each of these imaginaries reflects not only competing political philosophies but also different configurations of innovation systems. The libertarian

Network State emphasizes venture capital and entrepreneurial initiative;

Network Sovereignties seek to mobilize cooperative traditions;

Algorithmic Nations foreground the role of public institutions and community governance.

Despite these variations, what is largely missing from both the promotional narratives of Web3 and much of its critical scholarship is sustained attention to systemic inequalities [

23]. Analyses often focus on whether platforms are technically decentralized, without asking whether they are socially inclusive or accountable [

33]. A ledger distributed across thousands of nodes may still be governed by a handful of actors. A DAO may issue governance tokens to thousands of members; yet, if only a small minority participate in decision-making, governance remains effectively centralized. Tokenomics may reward early adopters while marginalizing latecomers and non-technical participants. In short, decentralization does not equate to democratization.

Innovation systems theory provides tools to move beyond this narrow focus. By emphasizing the institutional and social dimensions of innovation, it invites us to ask different questions [

36]: What kinds of learning processes are being fostered in Web3 communities? How inclusive are the governance structures? What roles do states, cooperatives, and civil society play in shaping outcomes? Are innovation trajectories oriented toward speculative financial gain or toward addressing collective challenges? These questions redirect attention from the architecture of protocols to the architecture of participation, accountability, and solidarity.

The gaps become clear when one compares the celebratory rhetoric of Web3 with its empirical realities. Despite the claim that blockchains are inherently transparent, opacity often characterizes token distribution and decision-making. Despite promises of global inclusion, infrastructural barriers prevent participation by those without stable internet access, affordable hardware, or financial literacy. Despite narratives of disintermediation, new intermediaries—venture capital firms, centralized exchanges, and “whales”—play decisive roles in shaping outcomes. These contradictions underscore the need to evaluate Web3 not only as a technical infrastructure but as an evolving innovation system.

In this sense, the promise of Web3 is both real and limited. It demonstrates that alternative models of digital coordination are technically possible [

34]. Yet whether these possibilities translate into systemic transformation depends on the governance frameworks, institutional supports, and normative orientations that accompany them. Just as national innovation systems in the twentieth century directed resources toward space exploration, health, or defense, the question for the twenty-first century is whether Web3 can be embedded in innovation systems oriented toward equity, solidarity, and sustainability.

Web3 remains largely oriented toward speculative financialization, individual sovereignty, and technical experimentation. The absence of robust institutional frameworks leaves governance vulnerable to elite capture. Cooperative traditions, data justice initiatives, and public policy interventions remain marginal rather than central. The task for scholars, policymakers, and practitioners is therefore to reimagine Web3 not merely as a set of decentralized protocols but as part of innovation systems that can be steered toward public value. This requires integrating insights from political economy, critical platform studies, and innovation theory, bridging disciplinary silos to develop a richer account of how digital infrastructures are shaped and what futures they enable.

In reframing Web3 through innovation systems, we gain a more precise understanding of Nelson’s paradox in the digital era. The capacity to design distributed ledgers, execute complex transactions without intermediaries, or create algorithmically governed communities is the equivalent of reaching the Moon. However, the persistence of digital exclusion, precarious labor, and inequitable governance represents new ghettos. Without systemic interventions, the paradox will repeat itself: extraordinary technical achievements coexisting with deepening social inequalities. Innovation systems theory offers the conceptual tools to prevent this outcome, reminding us that technological progress must be embedded in social contracts, institutional safeguards, and political commitments. The promise of Web3, if it is to be realized, depends not on the brilliance of code alone but on the innovation systems in which that code is situated (

Figure 1).

3. Methods: Empirical Insights and Action Research Ethnography

The argument that decentralization alone is insufficient to guarantee democratization requires both conceptual elaboration and empirical grounding. To this end, the analysis draws on a multi-year ethnography of Web3 ecosystems conducted as part of a Fulbright UK–US Commission award between 2022 and 2025 (

https://fulbright.org.uk/people-search/igor-calzada/, accessed on 14 November 2025). The empirical corpus—anonymized field notes from governance forums, transcripts from semi-structured interviews, and comparative case coding—has been curated as an open dataset for transparency and reuse [

49]. Based in Silicon Valley, the author engaged in action research with DAO participants, blockchain developers, think tanks, cooperative experiments, and critical research networks [

58]. The fieldwork was multi-sited, extending to workshops in Washington, D.C., collaborations in Europe, and comparative case analysis of Global South initiatives. Methodologically ethnographic yet reflexive, the research did not only observe Web3 communities but actively participated in debates, forums, and pilot projects, producing insights that were both experiential and analytic.

Spanning Silicon Valley, transatlantic, and Global South contexts, the study combined participant observation, semi-structured interviews, and comparative case analysis [

50,

59]. It aligns with the innovation systems tradition [

7,

42,

43], which emphasizes learning, interaction, and context. By embedding himself in sites where Web3 protocols, DAOs, and federated infrastructures were debated and implemented, the author interrogated how ideals of decentralization translated—or failed to translate—into lived realities of participation, accountability, and solidarity.

This methodological stance reflects a principle of innovation systems research: innovation is not only technological but also a process of learning through interaction [

43]. Studying Web3 governance as an innovation system thus required capturing contestation and practice. Ethnography revealed how DAO decision-making, token distributions, and technical expertise shaped participation, often reinforcing exclusion and elite capture. Action research further acknowledged that the researcher is not a neutral observer but a participant embedded in networks of knowledge production, funding, and policy [

49]. This positionality shaped access and interpretation made explicit here to avoid reproducing the techno-determinist narratives that dominate Web3 discourse.

3.1. Action Research Ethnographic Design

The action research ethnographic design integrated three complementary components:

3.1.1. Participant Observation

Governance fora and technical venues were observed over multiple cycles, including DAO discussion spaces (e.g., MakerDAO, Uniswap, Polkadot), developer conferences (e.g., ETHDenver, Devcon), and federated social platform communities (e.g., Mastodon). Observations focused on agenda-setting dynamics, patterns of participation, discussion framing, and the translation of proposals into decisions. Observation notes were systematized and coded into themes (participation, transparency, capture, accountability mechanisms) documented in the Zenodo corpus [

49].

3.1.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

Interviews (n ≈ 60) targeted a cross-section of ecosystem actors: protocol developers, token governance participants, venture fund partners, cooperative organizers, and policy interlocutors. Guides covered governance processes, token distribution and voting, perceived barriers to participation, and views on accountability. All transcripts were anonymized and catalogued in the dataset [

49] (the author is fellow at Decentralization Research Centre (

https://thedrcenter.org/fellows-and-team/igor-calzada/ (accessed on 14 November 2025)). This fact pro-vided a good opportunity to engage with Washington DC summits and events (in Georgetown University;

https://www.igorcalzada.com/prof-calzada-has-contributed-to-data-cooperative-report-by-liberty-project-and-decentralization-research-centre-by-participating-at-georgetown-university-workshop-on-1-2-april-2025/ (accessed on 14 November 2025) and National Press;

https://www.igorcalzada.com/paper-presented-at-the-2024-equitable-tech-summit-national-press-club-washington-dc-usa-6-june-2024-equitable-tech-navigating-ai-blockchain-and-data-sovereignty/ (accessed on 14 November 2025)) and events in California such as Stanford University (

https://www.igorcalzada.com/invited-speaker-at-stanford-university-the-science-of-blockchain-conference-2023-sbc23-stanford-dao-workshop-31th-august-palo-alto-california-usa/ (accessed on 14 November 2025)), Edge City in Healdsburg, in Sonoma County, California (

https://www.igorcalzada.com/exploring-coordi-nations-and-new-network-sovereignties-research-workshop-and-public-conference-healdsburg-california-usa-17-27-june-2024/ (accessed on 14 November 2025)) and SOAM Residence program in Network Sovereignties (

https://www.igorcalzada.com/soam-network-sovereignties-residence-programme-may-october-2024-selected-resident-ammersee-germany-https-soam-earth-work-soam/ (accessed on 14 November 2025))).

3.1.3. Comparative Case Analysis

Cases were selected for theoretical contrast and empirical salience: Global North ecosystems (Ethereum, MakerDAO, Uniswap, Mastodon) and Global South experiments (Celo, Grassroots Economics in Kenya, GoodDollar). A common coding frame captured governance model, participation practices, intermediaries, infrastructural dependencies, and integration with legal-institutional arrangements.

To ensure robustness and reproducibility, the analysis applied a multi-source triangulation strategy, combining ethnographic, documentary, and quantitative evidence. Observational insights from governance fora were cross-validated with publicly available on-chain data and community analytics. DAO turnout rates were retrieved from DeepDAO.io and Tally.xyz dashboards and compared with archived governance snapshots for MakerDAO, Uniswap, and Aave. Token-distribution concentration was assessed using Gini coefficients and top-wallet share metrics published in these dashboards. Forum participation patterns were analyzed through message-count statistics and interaction frequency data across official discussion spaces (Discourse, Discord, and Telegram).

These quantitative indicators were integrated with semi-structured interview findings and ethnographic field notes within the NVivo environment to align observed behaviors with measurable participation dynamics. This triangulation approach enabled validation of participation asymmetry claims through convergent evidence across data types—observational, documentary, and computational—rather than relying solely on qualitative inference.

This multi-sited, mixed-method approach is consonant with innovation systems research, which emphasizes interactive learning and institutional context [

7,

42,

43]. It also aligns with a Polanyian–Ostromian orientation by situating technical infrastructures within the social rules and collective arrangements through which they are governed [

36,

52,

53].

3.1.4. Case Selection and Validation

This study selected the comparative cases purposively to capture contrasting institutional and infrastructural contexts within Web3 innovation systems. The Global North set—Ethereum, MakerDAO, Uniswap, and Mastodon—represents capital-intensive, mature ecosystems that illustrate different governance architectures, from token-weighted DAOs to federated platforms. These cases were accessible during my fieldwork in Silicon Valley and Europe and are widely referenced in both academic and policy debates. The Global South set—Celo, Grassroots Economics, and GoodDollar—was chosen for their explicit inclusionary missions, partnerships with NGOs or cooperatives, and suitability for direct observation and collaboration during fieldwork in Latin America and Kenya.

To validate the comparison, this study triangulated multiple evidence sources: interview transcripts, DAO governance dashboards (DeepDAO.io, Tally.xyz), community and NGO reports (MakerDAO 2024; Celo Foundation 2024; Grassroots Economics 2024; GoodDollar Impact 2024), and peer-reviewed research [

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60]. This study cross-checked participation rates, governance-vote records, and forum analytics to ensure internal consistency and comparability across contexts. This triangulation confirmed the empirical basis of the Global North/Global South contrast while acknowledging the infrastructural asymmetries that shape participation.

The study employed purposive sampling to ensure representation across diverse roles and contexts within seven Web3 ecosystems (Ethereum, MakerDAO, Uniswap, Mastodon, Celo, Grassroots Economics, and GoodDollar). Approximately sixty participants were interviewed between 2022 and 2025, including protocol developers, DAO delegates, foundation staff, cooperative organizers, NGO partners, and policy interlocutors (Decentralization Research Centre and Liberty Project networks, among others). Recruitment was conducted through public governance forums, professional networks, conferences (Emerging Tech Summit in 2024 and 2025 and Stanford Blockchain Conference 2022 and 2023), and collaborations with NGOs and cooperatives in Latin America and Africa. Participation was entirely voluntary [

60].

Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to each interview, with confidentiality and anonymization procedures detailed in the consent form. No personally identifiable information is disclosed in the dataset. The action research complied with the ethical standards of the University of the Basque Country (EHU) and received formal approval from its Research Ethics Committee (Ref. SOC-2022-17-FULBRIGHT). Data management and storage adhered to the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

To enhance transparency and reproducibility, ref. [

57] includes the fieldwork action research developed since August 2022 as a result of the Fulbright Scholar-In-Residence. These materials are also archived alongside the Zenodo corpus [

49].

The article is grounded in a multi-sited action-research design conducted between 2022 and 2025 across North America, Europe, and the Global South. The approach combined participant observation, documentary analysis, and semi-structured interviews to capture governance dynamics in seven Web3 ecosystems. The researcher’s involvement in academic and policy networks facilitated access to relevant actors and decision-making spaces, yet analytic distance was maintained through systematic triangulation and anonymization protocols.

Sampling followed a purposive and stratified logic to ensure heterogeneity across organizational types and regional contexts. Approximately sixty participants were selected according to three main criteria: (i) direct involvement in governance (e.g., developers, delegates, cooperative leaders); (ii) geographical diversity, balancing Global North and South ecosystems; and (iii) institutional position within or outside formal foundations. This procedure minimized bias from proximity to the field and ensured analytical consistency across cases.

3.2. Analytical Orientation

Three analytical lenses guided interpretation:

3.2.1. Innovation Systems

Attention to the institutional embedding of technical change, capability formation, and directionality [

7,

9,

42,

43,

44].

3.2.2. Commons Governance

Assessment of rule clarity, membership boundaries, monitoring, sanctioning, conflict resolution, and multi-level (“polycentric”) coordination [

52,

53].

3.2.3. Political Economy of Platformization

Scrutiny of power concentration, elite capture, unequal participation, and the role of financial intermediation.

Coding memos and schema are archived with the dataset [

49].

3.3. Global North Web3 Platform Ecosystems: Ethereum, MakerDAO, Uniswap, and Mastodon

Ethereum’s governance is formally open, with public improvement proposals and extensive developer discussion [

21]. Field materials from protocol upgrade cycles indicate that agenda-setting and decision influence tend to consolidate around a relatively small constellation of actors (core contributors, client teams, and foundation-affiliated personnel) [

31]. While this pattern is not hidden—processes are documented and deliberations publicly recorded—it nonetheless exemplifies the gap between formal openness and effective influence. Interviews describe this consolidation as a pragmatic response to technical complexity rather than as intentional exclusion; however, from an innovation-systems standpoint, it remains a form of path-dependent centralization that conditions who can meaningfully intervene in protocol direction.

MakerDAO presents a canonical case of token-weighted governance. Observational logs and interview testimony converge on two recurrent features: (a) low routine turnout in governance votes (often in the single-digit percentage range of eligible token holders), and (b) disproportionate agenda-setting power by a small subset of large holders and recognized delegates. Documentation of “temperature checks,” requests for comment, and formal executive votes illustrates that deliberation is procedurally inclusive, yet practically skewed by expertise, attention costs, and capital concentration. In Polanyian terms, the governance of a monetary commons (a stablecoin) remains partially disembedded from broader social safeguards; in Ostromian terms, boundaries are clear, but monitoring and sanctioning mechanisms to counter strategic abstention or concentrated control are under-specified [

49].

Uniswap’s community governance employs delegation, off-chain signaling, and on-chain voting. Field notes record recurring frictions: proposal complexity raises cognitive barriers for casual participants; discussion migrates across forums, Discord, and off-platform channels; and high quorums for impactful changes incentivize pre-coordination among a small set of well-resourced actors. Interviewees characterize this as “pragmatic centralization,” necessary for timely decision-making, yet it produces a persistent participation gradient between a highly active inner circle and a largely quiescent periphery. This gradient is consistent with innovation systems literature on capability formation—participation follows resources, routines, and learned roles [

43].

Mastodon’s federated architecture avoids token governance and corporate platform control, distributing authority across instance administrators. Ethnographic observation highlights the benefits of pluralism and local rule-setting alongside coordination challenges (content moderation spillovers, federation politics, compatibility frictions). Polycentric governance is present in form but limited in function when cross-instance controversies arise, revealing the need for scalable conflict-resolution arenas and meta-protocols—precisely the kind of institutional design Ostrom’s principles anticipate.

Across these cases, technical decentralization coexists with governance concentration. Participation is patterned by specialized knowledge, time availability, and capital intensity; intermediaries (foundations, core teams, large token holders, recognized delegates) become indispensable coordinators. In innovation systems terms, these are signs of institutional maturation—but without explicit accountability mechanisms, the result is what Nelson’s paradox predicts: exceptional technical feats paired with persistent participation asymmetries.

3.4. Global South Web3 Ecosystems: Celo, Grassroots Economics, and GoodDollar

Celo positions mobile-first stable assets as rails for everyday transactions and remittances. Field materials from pilots and meetups in Latin America document the promise of low-friction transfers but also infrastructural constraints: intermittent connectivity, device fragility, currency volatility, and limited digital literacy. Interviews with ecosystem partners note that adoption is most robust where civil-society intermediaries co-produce onboarding and dispute-resolution practices—an Ostromian insight about local rule fit. Where such intermediation is thin, usage reverts to speculative holding or drops off.

Grassroots Economics integrates community inclusion currencies (CICs) with blockchain-based accounting to stabilize local exchange networks. Observed workshops and governance meetings illustrate strong local ownership and clear membership boundaries, aligning with commons design principles. At the same time, scaling beyond dense social ties proved challenging; sustaining the system required anchors such as schools, clinics, or cooperatives capable of underwriting redemption points and dispute mediation. The case demonstrates that federation of community currencies is feasible where nested governance exists—echoing Ostrom’s polycentricity—but remains fragile where donor cycles or staff turnover disrupt continuity [

60].

Although Grassroots Economics operates without a formal token-voting architecture, transaction analytics and council rosters indicate similar concentration patterns, with approximately 35% of local currency flow managed by the top 10% of community accounts. Yet, participation rates in decision meetings (≈18%) remain significantly higher than in most token-based DAOs. This hybrid community-governance structure thus provides a useful empirical counterpoint to Web3’s algorithmic decentralization claims.

GoodDollar operationalizes a universal basic income logic via daily token disbursements. Interviewees in Latin America reported ambiguous use-value where local merchant acceptance was weak; tokens often functioned as speculative instruments rather than means of exchange. This underscores a Polanyian concern: without institutional embedding—merchant networks, consumer protections, redress mechanisms—the “income” remains nominal. Where community partners negotiated acceptance and provided literacy training, the program displayed more consistent welfare effects.

Experiments explicitly aimed at inclusion tend to succeed where intermediary institutions—NGOs, cooperatives, local governments—translate cryptographic affordances into locally legible rules, roles, and recourse. Absent that embedding, novelty effects fade and adoption stalls [

60]. The contrast with Global North cases is instructive: where the North exhibits oligarchic concentration inside capital-dense ecosystems, the South exhibits infrastructural exclusions that limit the very possibility of governance participation [

59].

3.5. Comparative Insights for Innovation Systems

Global North and South cases reveal uneven geographies of Web3. In the North, oligarchic governance dominates capitalized ecosystems; in the South, infrastructural exclusion and dependency prevail. Both show that decentralization alone is insufficient [

33]. The same protocols yield divergent outcomes depending on the innovation systems in which they are embedded: in Silicon Valley, venture capital and speculative finance shape trajectories, while in Nairobi or São Paulo, infrastructural inequality and grassroots mobilization prevail.

These contrasts affirm that Web3 must be situated within innovation systems theory. As Nelson and Lundvall argued, innovation trajectories are context-dependent, shaped by institutions, governance, and cultural practices. Without mission-oriented direction, Web3 ecosystems risk defaulting to market logics that reproduce exclusion [

44].

Placing North and South materials side by side yields three robust patterns (

Table 1):

In token-governed systems, single-digit turnout is common across routine votes [

49]. Expertise, capital, and attention costs sort participants into nested tiers. This is not simply apathy; it reflects the capability requirements of meaningful participation and the transaction costs of deliberation at scale.

Foundations, core dev teams, liquidity providers, community NGOs, and co-ops act as coordinating nodes [

6]. Rather than seeing intermediaries as antithetical to decentralization, innovation systems theory suggests recognizing, formalizing, and holding them accountable as public-interest institutional complements to code.

Where nested, interoperable arenas exist (clear membership, monitoring, conflict resolution, graduated sanctions), decentralization becomes governable. Otherwise, fragmentation (as in some fediverse dynamics) or capture (as in some token fora) prevails. Ostrom’s design principles offer a practical checklist; Polanyi’s double movement explains why countervailing protections emerge—or fail to.

These findings help explain why “decentralization” so often disappoints as a proxy for “democratization.” Distributed ledgers are necessary but not sufficient; the decisive variable is the quality of institutional embedding.

After

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3 have been included to enhance the former by providing clearer variable definitions and data sources.

To facilitate comparison between Global North and Global South cases, this article calculates three standardized indicators for each ecosystem:

Voter Turnout (%): average proportion of eligible token holders (or members) participating in formal governance votes or community decisions.

Gini of Voting Power: concentration index measuring inequality in token-weighted voting rights or transaction influence.

Proposal-Origin Diversity (%): proportion of proposals or governance initiatives originating from outside core developer or foundation entities.

Where token-based data were unavailable (for instance, in Grassroots Economics), I used equivalent proxies derived from council attendance and transaction distribution records. These indicators, summarized in

Table 3, provide a consistent comparative lens to assess decentralization, inclusion, and institutional diversity across heterogeneous governance models.

By applying standardized indicators across the seven ecosystems, I can compare decentralization outcomes on equal terms. The analysis reveals that technical decentralization in Global North DAOs often coincides with low participatory diversity, whereas community-based and federated models in the Global South demonstrate more balanced participation and proposal generation despite smaller scale and resource constraints.

3.6. Methodological Reflexivity and Positionality

Conducting action research in Silicon Valley meant engaging with actors who are both architects and beneficiaries of Web3 infrastructures. The author’s position as a European scholar, supported by a Fulbright US-UK Award, provided access but also shaped interpretation. The vantage point was largely Global North, even as perspectives from the Global South were sought. This asymmetry reflects epistemic inequality: Web3 narratives are dominated by Northern actors, while Southern initiatives remain underrepresented. Recognizing this positionality is part of the analytic frame, underscoring that innovation systems are as much about knowledge production as technical protocols. Early interventions at Stanford blockchain conferences (2022–2023) on data cooperatives (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mTT0tCix43E (accessed on 14 November 2025)) resonate with the recent Liberty Project report, connecting lessons from earlier publications [

60].

The article’s standpoint reflects an academic position embedded in European innovation and governance research networks, combined with multi-sited ethnographic fieldwork conducted between 2022 and 2025 in Silicon Valley, Washington D.C., Europe, and selected Global South contexts (including Kenya, Nigeria, and Latin America). This positioning facilitated access to Global North blockchain foundations and institutional intermediaries, while access in community-based or grassroots initiatives required longer trust-building processes. Consequently, the asymmetry of access could have influenced the relative depth of observation and interpretation across cases.

To mitigate these structural biases, the analysis incorporated triangulation across data types (on-chain analytics, interviews, and observation) and geographies. All qualitative data were anonymized, and interpretations of governance dynamics were validated through member-checking with participants from different institutional strata (developers, NGO facilitators, and cooperative coordinators). Analytical consistency was further ensured through cross-referencing between empirical material and secondary documentation from independent repositories and open dashboards. These procedures aimed to maintain reflexivity while securing analytic coherence across heterogeneous sites.

3.7. Implications for Digital Journal

For Digital journal, the methodological contribution is threefold. First, the open dataset provides an auditable basis for claims about participation, capture, and institutional embedding [

49,

60]. Second, the multi-sited design clarifies how identical technical protocols are refracted through different innovation systems, producing divergent social outcomes—Nelson’s paradox in contemporary form. Third, the Polanyian–Ostromian lens supplies a constructive path forward: rather than diagnosing failure at the level of code, it points to the design and institutionalization of hybrid, polycentric, and accountable governance—data cooperatives, federated infrastructures, legally recognized trustees, transparency and audit obligations for delegated roles, and measurable standards of participation and redress.

Taken together, the evidence indicates that Web3 will deliver on its democratic promise only when embedded within innovation systems that align technical affordances with social protections and collective capabilities. In other words, reaching the Moon requires, and does not substitute for, governing the ghetto.

4. Discussion and Results: The Illusion of Decentralization, Innovation Systems (And the Persistence of ‘Platform Ghettos’) and Three Governance Imaginaries (For Post-Westphalian Sovereignties)

The article reinterprets Schumpeter, Polanyi, and Ostrom through a shared concern with how innovation systems mediate between technological change and institutional order. Schumpeterian disruption frames the creative tensions underlying Web3’s economic imaginaries; Polanyi situates them within the broader dynamic of market disembedding and re-embedding; and Ostrom offers a design vocabulary for collective governance under digital conditions. Rather than elaborating each tradition separately, the analysis highlights their convergence in explaining why technological decentralization rarely translates into distributed power.

The notion of Algorithmic Nations extends this synthesis by contrasting algorithmically coded governance with Network States (entrepreneurial communities claiming digital sovereignty) and Network Sovereignties (corporate or foundation-led jurisdictional ecosystems). Algorithmic Nations emerge when algorithmic coordination begins to substitute for political mediation while still depending on state infrastructures, legal frameworks, and human governance. They thus reveal decentralization’s double bind: autonomy without full sovereignty.

Yet decentralization is not entirely illusory. Instances of incremental reform—such as transparent delegate dashboards in Uniswap, validator inclusion grants in Celo, and participatory treasury mechanisms in Grassroots Economics—illustrate partial diffusion of power and procedural learning. These small wins underscore that algorithmic governance can, under certain institutional conditions, evolve toward greater accountability and inclusion, even if unevenly.

4.1. The Illusion of Decentralization

The paradox at the heart of Web3 decentralization lies in the gap between its emancipatory rhetoric and empirical realities. Advocates present blockchain, DAOs, and token-based governance as antidotes to monopolies and surveillance, promising distributed authority [

16]. Yet studies show low participation, concentrated token distribution, and governance dominated by technically literate, capital-rich actors [

31,

33]. Rather than dispersing power, these structures often entrench oligarchic arrangements [

29]. This illusion of decentralization is observable across ecosystems in both the North and South, with DAOs and token governance drifting far from cooperative ideals [

60].

Fieldwork (2022–2025) and comparative cases confirm oligarchic tendencies. In Ethereum, decision-making is concentrated among core developers and validators, despite the nominal openness of the EIP process. MakerDAO, despite its pioneering status, shows governance turnout below 10 percent, often under 5 percent [

13]. In DeFi, concentration is stark: five wallets control over 50 percent of Uniswap’s voting power, while Aave and Polkadot see less than 2 percent of token holders participate [

15]. These metrics expose the persistence of gatekeeping and wealth-weighted governance. Federated alternatives such as Mastodon and BlueSky avoid token logics but face fragmentation, moderation challenges, and scalability limits [

33].

Global South initiatives offer partial counterpoints. Celo’s mobile-first system supports 1.7 million wallets; Grassroots Economics in Kenya uses Community Inclusion Currencies with 40,000 users; GoodDollar distributes crypto-UBI to over 600,000 users. These illustrate Web3’s inclusionary potential. Yet governance remains fragile: Celo’s proof-of-stake favors capital holders; Grassroots Economics depends on local champions; and GoodDollar suffers participation asymmetries akin to Northern DAOs. Digital divides in access and literacy further constrain impact [

4].

Governance participation and concentration metrics were validated through publicly available analytics. Ethereum’s EIP process involves around 300 active contributors out of thousands of token holders; MakerDAO’s governance turnout fluctuated between 4 and 8% during 2023–2024 (DeepDAO.io, 2024), while Uniswap’s five largest wallets hold approximately 53% of voting power (DefiLlama, 2024). In contrast, Mastodon reports around 13,000 active administrators across 11,000 federated instances, though participation in moderation and decision-making varies widely (Mastodon Admin Stats, 2024). Celo maintains roughly 1.7 million wallet addresses, but validator concentration remains high, with the top 20 validators controlling nearly 60% of staking power. Grassroots Economics’ Community Inclusion Currencies engage over 40,000 active users, and GoodDollar distributes tokens to over 600,000 registered participants, though fewer than 10% take part in governance discussions (GoodDollar Dashboard, 2024). These figures substantiate the paper’s core finding that participation asymmetries and concentration of influence persist across decentralized ecosystems.

4.2. Innovation Systems (And Persistent Exclusion of ‘Platform Ghettos’)

To understand why exclusion persists despite the rhetoric of openness, it is necessary to situate Web3 within the broader framework of innovation systems. Innovation systems theory [

7,

43,

44] emphasizes the co-evolution of technologies, institutions, and social relations. It is not only technological breakthroughs that matter but also the systemic embedding of innovations within social and institutional contexts.

Web3 ecosystems, however, have largely privileged technological and financial infrastructures over inclusive institutional design. Governance models often rely on token-based participation without addressing structural inequalities in access to tokens, digital literacy, or broadband connectivity. The result is a system that generates technical innovation at extraordinary speed—akin to Nelson’s metaphor of reaching the Moon—while leaving social inequalities unaddressed, the “ghettos” of digital exclusion [

9].

From an innovation systems perspective, the illusion of decentralization reflects a failure to integrate solidarity, accountability, and democratic participation into the design of Web3 governance. While blockchain provides the technical substrate for distributed ledgers, the social and institutional frameworks that determine how these ledgers are governed remain narrow, privileging early adopters, developers, and venture capital-backed entities. The emphasis on “code is law” neglects the role of institutional design in shaping equitable participation, thereby reinforcing digital stratification.

Fieldwork and policy engagement since 2022 have revealed three dominant governance imaginaries shaping debates on Web3 and post-Westphalian sovereignty [

37,

46]. These three paradigms—Network States [

30,

48], Network Sovereignties [

26], and Algorithmic Nations [

29]—represent competing visions of how decentralized technologies might reconfigure governance beyond the nation-state [

12].

Across field sites, participants described both the promise and frustrations of decentralized governance. One long-time MakerDAO delegate noted, “It’s open in theory, but unless you have time to read governance chat all day, your voice doesn’t move the needle.” In contrast, a community facilitator in the Grassroots Economics network in Nairobi reflected, “Here, people actually show up. We argue about prices at the market, but the money circulates among us—it feels real.”

These accounts highlight the divergence between token-based and community-based participation: in the Global North, power often consolidates around financial capital and technical literacy, while in the Global South, inclusion depends heavily on the mediating role of NGOs, cooperatives, and local anchors. As a result, capability formation is sustained less by algorithmic openness than by institutional and social embedding.

4.3. Three Governance Imaginaries (For Post-Westphalian Sovereignties)

Network States epitomize the crypto-libertarian ideal: market-first, sovereignty-through-membership communities that operate like start-ups [

48]. Their reliance on tokenized governance privileges those with financial and technical resources, producing elite enclaves. While they embody the rhetoric of decentralization, their governance is often highly centralized around founders or core developers, an “elite decentralization” that remains inaccessible to most.

- ○

Core claim. Market-first, sovereignty-through-membership communities oriented around tokenized governance and entrepreneurial acceleration [

30,

48].

- ○

Empirical fit. The Global North rows in

Table 1 (e.g., Ethereum, MakerDAO, Uniswap) echo Network State dynamics: technically open processes that, in practice, centralize agenda-setting in core dev teams and large token holders. Participation gradients and “pragmatic centralization” map onto the participation asymmetry and intermediary indispensability patterns.

- ○

Polanyi–Ostrom diagnosis. High risk of disembedding (market logics outrunning social safeguards) and thin application of Ostromian design—boundaries are clear, but monitoring, sanctioning, and nested arenas are partial.

- ○

Main risk. “Elite decentralization”: wealth-weighted control and off-chain coordination among insiders reproducing shareholder-style governance.

- ○

Hybrid levers. Mission-oriented reforms: quadratic/conviction voting, delegate caps, mandatory impact audits; multi-stakeholder RFC councils and stewardship boards; legal recognition of fiduciary duties for foundations and delegates.

Network Sovereignties attempt to foreground commons-based governance, embedding cooperation, reciprocity, and ethical stewardship into decentralized infrastructures [

26]. These models resonate with Ostrom’s principles of polycentric governance and emphasize subsidiarity—decision-making as close as possible to affected communities [

52,

53]. However, empirical evidence shows that even here, participation asymmetries persist. Digital literacy and access disparities create opportunities for manipulation by small groups, limiting inclusivity despite the cooperative ethos.

- ○

Core claim. Commons-centric governance that foregrounds cooperation, reciprocity, and ethical stewardship via polycentric architectures [

26,

34,

52,

53].

- ○

Empirical fit. Mastodon and Grassroots Economics illustrate the promise and limits: strong local rule-setting and community ownership, yet under-institutionalized nesting leads to fragmentation (fediverse disputes) or fragile scale (community currencies). These precisely instantiate

Table 1’s finding that polycentricity must be explicitly institutionalized to travel beyond close-knit contexts.

- ○

Polanyi–Ostrom diagnosis. Solid local embedding with clear boundaries and monitoring; gaps in conflict-resolution arenas and scalable nesting.

- ○

Main risk. Governance drift toward recentralization (to overcome coordination costs) or local-elite capture when literacy and participation are uneven.

- ○

Hybrid levers. Inter-instance compacts, portability standards, shared moderation commons; federated treasuries and league-style meta-governance for community currencies; transparency and redress obligations for delegated roles.

Algorithmic Nations advance an emancipatory imaginary rooted in cultural sovereignty, data cooperatives, and community-led governance [

29]. Indigenous groups, e-diasporas, and stateless nations see Algorithmic Nations as vehicles for self-determination. Algorithms and federated data systems mediate governance, with inclusivity and transparency as explicit goals. Yet the reliance on data infrastructures can itself reproduce exclusion, as communities without reliable digital access remain marginalized. Algorithmic Nations thus embody both the promise of solidarity and the risk of algorithmic gatekeeping.

- ○

Core claim. Emancipatory, culturally rooted sovereignty built on data commons, city-regional coordination, and federated infrastructures.

- ○

Empirical fit. Celo and GoodDollar highlight the enabling role of intermediaries (NGOs, cooperatives, merchant networks) for inclusion, but also the constraint of infrastructural inequalities (connectivity, literacy, volatility). Where partners co-produce onboarding and dispute resolution, value realization improves; where they do not, systems slide toward speculative drift—a

Table 1 pattern of partial embedding.

- ○

Polanyi–Ostrom diagnosis. Strong normative commitment to embedding and inclusion; uneven realization of Ostromian checks (redress, sanctioning, convertibility backstops) at scale.

- ○

Main risk. Algorithmic gatekeeping and nominal inclusion: tokens or data rights without the institutional complements that render them usable and enforceable.

- ○

Hybrid levers. Merchant compacts and convertibility guarantees; community stewards with formal mandates; data trusts/cooperatives aligning legal rights with protocol design; public-interest funding for local capability formation.

Comparing these imaginaries reveals the persistence of exclusion across paradigms. Network States privilege the wealthy and technologically literate; Network Sovereignties face risks of governance capture by local elites; Algorithmic Nations may exclude those lacking digital capacity. All three struggle to reconcile the technical architecture of decentralization with the social imperative of democratization.

The comparative patterns surfaced in

Table 1—participation asymmetries, indispensable intermediaries, and the need for explicit polycentric institutionalization—provide a bridge from empirical cases to the imaginaries that orient Web3 governance debates. Read through this innovation-systems lens (Nelson; Lundvall; Mazzucato) and the Polanyi–Ostrom synthesis, each imaginary can be evaluated not by the elegance of its protocol, but by how it embeds safeguards, distributes capabilities, and institutionalizes accountability across scales. See resulting

Table 4.

Variable definitions are as follows:

Core governance logic: ideological and operational basis of each imaginary.

Innovation-systems reading: how institutional diversity, learning, and mission-orientation shape outcomes.

Ostrom/Polanyi embedding focus: degree of commons design (Ostrom) and social re-embedding (Polanyi).

Empirical proxies & exemplars: representative cases drawn from

Table 1 fieldwork (Ethereum, MakerDAO, etc.).

Main risks: systemic vulnerabilities revealed by field comparison.

Mission-oriented hybrid levers (law + code): institutional innovations proposed for accountability and inclusion.

Evaluation metrics for democratic resilience: quantitative/qualitative indicators (turnout %, Gini of voting power, dispute-resolution latency, etc.) used to assess governance performance.

Suggested source note:

Data synthesized from fieldwork corpus (2022–2025), DAO analytics (DeepDAO.io, Tally.xyz), federated-platform archives (Mastodon Admin Stats 2023–2024), and NGO partner reports (Grassroots Economics 2024; GoodDollar 2024). Theoretical framing draws on Nelson [

7], Lundvall [

43], Mazzucato [

44], Polanyi [

36], Ostrom [

52,

53].

4.4. Comparative Synthesis and Link-Back to Findings

Evidence from the seven fieldwork cases confirms the recurring asymmetries that underpin the illusion of decentralization. In the Global North, Ethereum, MakerDAO, and Uniswap exhibit high technological maturity but strong concentration of influence: fewer than 2–5 percent of token holders regularly vote, and decision-making authority is often clustered in developer foundations or large liquidity providers. Mastodon, as a federated network, offers a contrasting cooperative model but faces fragmentation and uneven moderation across instances, revealing the limits of scale without designed nesting. In the Global South, Celo demonstrates financial inclusion potential with 1.7 million wallets, yet proof-of-stake mechanisms still reward capital holders. Grassroots Economics shows locally embedded reciprocity through 40,000 Community Inclusion Currency users, though governance depends on a handful of local champions. GoodDollar with more than 600,000 participants, succeeds in symbolic redistribution but faces low governance participation and volatility in adoption. Across these cases, inclusion improves when intermediaries—NGOs, cooperatives, or merchant networks—mediate access and build capabilities, suggesting that institutional complements, rather than purely technical design, determine whether decentralization translates into democratic resilience.

Across imaginaries, the same three empirical regularities from

Table 1 reappear:

First, participation asymmetry is structural unless capability formation and time/attention costs are addressed;

Second, intermediaries are unavoidable and therefore must be recognized, resourced, and held to fiduciary standards;

Third, polycentric designs require formal nesting (clear membership, monitoring, sanctioning, conflict resolution, and inter-arena compacts) to avoid either fragmentation (fediverse) or capture (token fora).

Put differently, Network States excel at speed but under-embed; Network Sovereignties embed locally but under-nest; Algorithmic Nations aim to nest and embed yet depend on institutional complements that are frequently missing in low-infrastructure contexts.

4.5. Operationalizing Inclusion and Capability Formation in Global South Ecosystems

In the three Global South cases—Celo, Grassroots Economics, and GoodDollar—this article operationalizes inclusion as the ratio of active participants to total registered members within each ecosystem’s governance or transaction network. Capability formation was assessed through evidence of participants’ increasing ability to propose initiatives, sustain activity, and benefit from redistributive or cooperative mechanisms over time.

Celo (2022–2025) recorded an average of 8000–10,000 monthly active wallet addresses in governance or community staking, representing approximately 0.9% of total wallet holders; retention over three months averaged 62%. Grassroots Economics based on ethnographic observation and Sarafu Network analytics, reported ≈28 community groups across Kenya with an average participation rate of 18% in council deliberations and a retention rate above 70% after one year of use.

GoodDollar data (2022–2025) show that roughly 15–20% of registered users participated in distribution or community decision processes, with 60% monthly retention in active wallets.

Across these cases, inclusion is not merely numerical but processual—linked to participants’ evolving capacities to engage in governance and benefit from token or credit circulation. These findings indicate that capability formation depends less on technological access and more on institutional and educational embedding within each ecosystem.

4.6. Implication for Post-Westphalian Sovereignties

If these imaginaries are treated as innovation-system configurations rather than purely technical blueprints, their democratic prospects hinge on Polanyian re-embedding (social protections, due process, public value) and Ostromian design (participatory rules, monitoring, graduated sanctions, and nested, interoperable arenas). The policy program that follows is mission-oriented [

44]: hybrid governance that braids law and code—data cooperatives and trusts, fiduciary duties for delegates and foundations, portability and interoperability mandates, participatory budgeting and impact audits, and measurable standards for participation, redress, and inclusion.

In short,

Table 1’s North/South contrasts and the field evidence converge: decentralization is necessary but not sufficient. Only when imaginaries are institutionalized as polycentric, accountable innovation systems do they move beyond reaching the Moon toward governing the ghetto—turning technical prowess into democratic resilience.

The comparative findings vividly echo Richard R. Nelson’s paradox from The Moon and the Ghetto: societies capable of landing a man on the Moon often remain unable to solve the persistent injustices of the “ghetto.” Web3 reproduces this paradox in digital form. The field evidence demonstrates remarkable technical sophistication—cryptographic consensus, automated governance, and global-scale coordination—but continued failure to embed these innovations within equitable social and institutional frameworks. The Global North cases exhibit “Moon-like” technological feats with concentrated governance, while the Global South experiments reveal the enduring “ghetto” of infrastructural inequality and capability asymmetry. Interpreted through Nelson’s innovation-systems lens, the illusion of decentralization thus represents not a technological deficit but an institutional failure: the absence of systemic embedding that aligns innovation with inclusion. Overcoming Nelson’s paradox in digital governance requires integrating Mazzucato’s mission-oriented public purpose and Ostrom’s polycentric accountability into the design of decentralized systems—so that technological reach is matched by social depth.