1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, declared globally in March 2020, disrupted social, economic, and institutional norms, generating widespread uncertainty and forcing rapid societal adaptation. In its aftermath, the accelerated integration of smart-enabled technologies has redefined everyday life, normalizing remote work, online learning, cashless transactions, and an on-demand, hyper-connected lifestyle [

1,

2]. Digitalization has emerged as a transformative force, fundamentally reshaping managerial practices across both the private and public sectors. The integration of information and communication technologies (ICTs) has enabled organizations to automate processes, enhance productivity, and facilitate data-driven decision-making, thereby challenging traditional management paradigms. In the public sector, e-government initiatives leverage ICT to deliver services via digital platforms, revolutionizing public service delivery and strengthening interactions between governments and citizens [

3]. E-government has become a cornerstone of public sector reform globally, fostering transparency, accountability, and efficiency [

4,

5].

A key driver of this transformation is the adoption of open innovation models, which promote knowledge creation through both internal and external collaboration, breaking down organizational silos [

6]. By embracing open innovation, governments can transition from traditional service delivery to integrated e-government systems, utilizing standardized digital identification to provide faster and more user-centric services. The benefits of e-government are well-documented, including reduced corruption, improved administrative efficiency, enhanced service quality, and the promotion of e-democracy and citizen engagement [

7,

8]. Citizens, as primary users, play an active role in the co-creation and continuous improvement of these services [

9].

The evolution of e-government has been closely linked to advances in ICT, particularly the proliferation of digital media [

10]. Governments increasingly utilize diverse platforms including official websites, social media, and multimedia content to raise public awareness and educate citizens about the value and use of e-government services [

11]. This trend is further propelled by citizen participation and open government initiatives [

12,

13].

Despite the widespread availability of e-government services, significant gaps remain in understanding the factors that limit their adoption, especially in developing countries. This knowledge gap constrains the realization of e-government’s full potential. Most research to date has focused on developed contexts, with limited attention to the unique challenges faced by developing nations, particularly in Africa [

14]. The diversity in social, cultural, political, economic, and technological readiness across countries complicates the application of universal models for e-government adoption. While perceived usefulness and ease of use are recognized as key determinants [

15], their mediating roles remain underexplored.

In Morocco, digitalization is central to national strategies aimed at modernizing the economy and enhancing global competitiveness. Initiatives such as Maroc Digital 2025 seek to promote ICT adoption across sectors. However, the extent to which digitalization acts as a disruptive force or a catalyst for innovation and efficiency remains an open question. The literature presents divergent perspectives: while some scholars highlight the potential for increased efficiency and innovation [

16], others caution against risks such as job displacement and the erosion of competitive advantage [

17].

Empirical evidence from Morocco reveals sectoral disparities in digital transformation. The private sector, particularly banking and industry, has made significant strides, with examples such as CIH Bank’s fully digital operations and OCP’s integration of IoT and AI in supply chains. In contrast, the public sector’s progress has been slower and more uneven, hindered by infrastructural limitations, coordination challenges, and low ICT adoption among public employees [

18].

Comparative experiences from countries like Estonia and Singapore demonstrate that successful digital transformation in the public sector requires more than technological investment. It depends on the creation of a supportive ecosystem, including robust infrastructure, coherent national strategies, adaptive regulatory frameworks, public–private partnerships, and a culture of open innovation. Mass media also plays a pivotal role in promoting e-government adoption by raising awareness and educating citizens.

In this context, the present study examines the critical role of mass media in facilitating the adoption of e-government services in Morocco, where integration has faced persistent challenges. Despite ongoing initiatives to advance digitalization within public administration, obstacles remain that hinder full digital integration. As Morocco seeks to accelerate its digital transformation and proactively develop digital administration, the advent of fifth-generation digital technologies promises to fundamentally reshape information exchange and public service delivery. This evolution raises five central research questions:

What is the role of media in promoting e-government adoption?

Which factors influence e-government adoption in the Rabat-Salé-Kénitra region?

How does digitalization affect citizen satisfaction with public services?

In what ways does media enhance citizens’ trust in digital transformation initiatives?

What challenges and opportunities exist for advancing electronic public administration in Morocco?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

To determine the sample size, Slovin’s formula was applied to ensure an adequate representation of the population [

68]. Given the limited number of individuals using e-government services in the region of Kénitra, Morocco, a sample size of approximately 311 respondents was deemed sufficient to represent the population with a 5% margin of error and a 95% confidence level. A voluntary sampling method was employed. Data collection was conducted using an online questionnaire, which was developed in consultation with experts in the field, resulting in 342 responses. Prior to the main data collection, a pilot test was carried out to evaluate the content and format of the questionnaire, ensuring alignment with the study’s objectives. Data from the pilot test were excluded from the final analysis. The questionnaire was distributed via online social media platforms, including Facebook, WhatsApp, and LinkedIn, during the period from 3 March 2024 to 15 May 2024. Combining the research question with the study’s context, the data collection focused on gathering respondents’ perceptions regarding the role of media in the adoption of e-government. According to a previous study by [

69], the age gap can influence individuals’ attitudes toward adopting new technologies, with people under 50 years old being more open to innovation.

The questionnaire’s layout and language were revised, and it was subsequently translated into Arabic to maximize the response rate. Of the 342 responses received, 311 were deemed valid (95.1% of the total), while 31 were excluded due to incomplete or inconsistent data. Only valid responses were analyzed to ensure the reliability, validity, and appropriateness of the data for hypothesis testing.

3.2. Survey Design

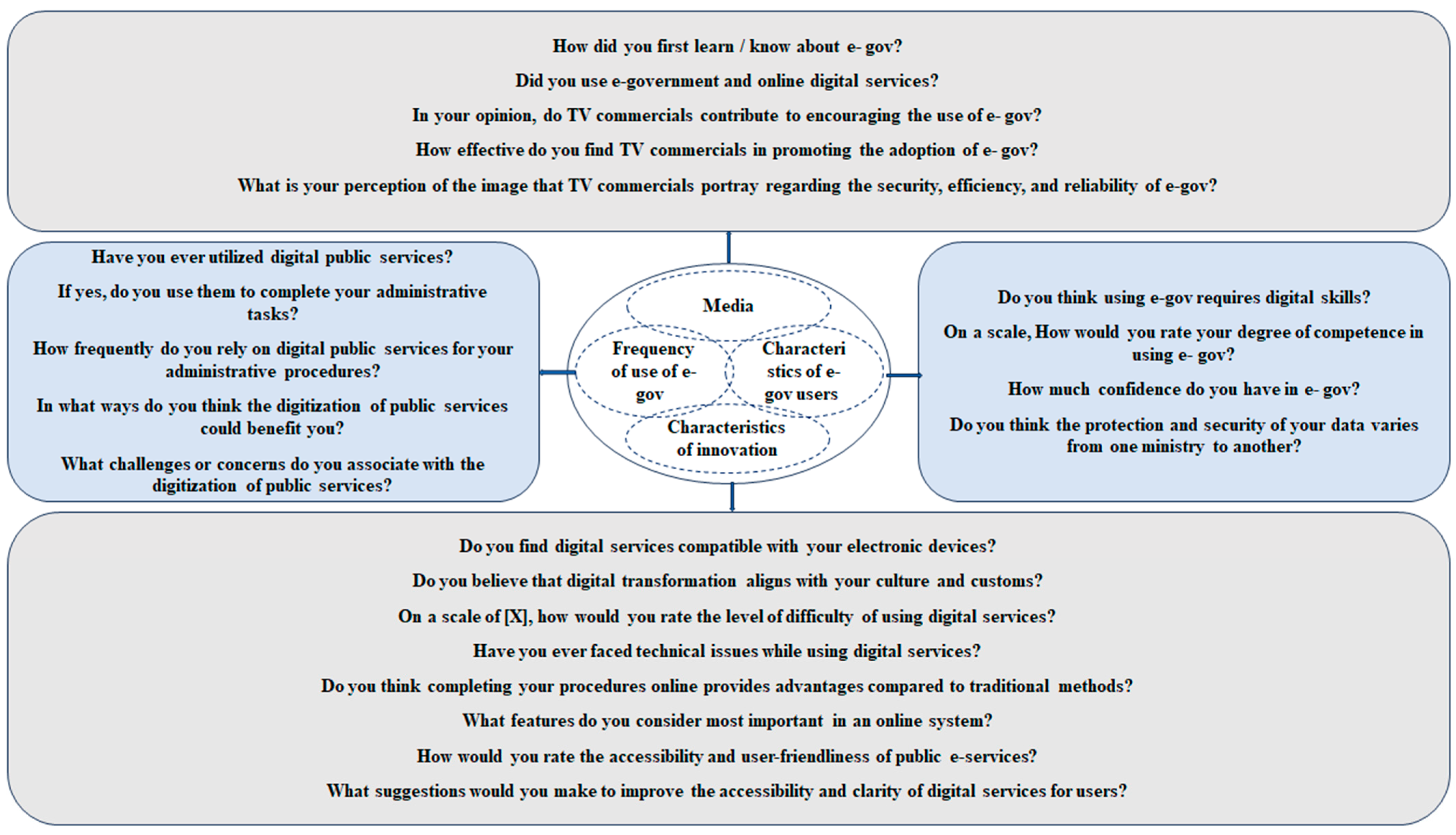

This study adopts a quantitative approach to analyze the impact of media on e-government adoption using a questionnaire consisting of 27 carefully designed questions. The questionnaire aimed to identify the various obstacles hindering the adoption of e-government in the Kénitra region. These questions were organized into five distinct sections, as illustrated in

Figure 1 to ensure ease of understanding for participants, the questionnaire was developed in Arabic.

The first section of the questionnaire presented demographic information about the respondents, including gender, age, occupation. The second section focused on “Habits and frequency of use of digital services.” The third section explored “the characteristics of the innovation”. The fourth section examined the “Characteristics of e-government users.” Finally, the fifth section addressed the “Role of media in e-government adoption”.

3.3. Data Analysis

In this study, the research model was evaluated using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) techniques, implemented using SmartPLS 4 software. SEM provides a comprehensive framework for testing hypotheses regarding relationships between observed and latent variables [

70]. This statistical approach integrates path analysis, factor analysis, and linear regression into a theoretical causal model, enabling the simultaneous estimation of both measurement and structural sub-models [

71].

The questionnaire items were adapted from prior studies on technology acceptance such as [

72,

73,

74,

75]. As this research adopts a quantitative approach, SPSS version 26.0 and SmartPLS were utilized to analyze the empirical data, ensuring high accuracy of the results. Prior to analysis, the data underwent a cleaning process to address errors from data collection, including the identification and removal of incomplete, abnormal, or extreme responses. This process, referred to as data monitoring, eliminates unusable responses, as recommended by previous studies [

76]. Data preparation preceded the final analysis, during which a reliability assessment was conducted on the 27 items outlined in the survey design.

Cronbach’s alpha serves as a metric for internal consistency, reflecting the extent of relationships within groups. It is a crucial measure of scale reliability, where a higher alpha value typically indicates that the items effectively measure the same underlying construct. However, the interpretation of alpha hinges on several factors, including the item count in the scale, the strength of inter-item correlations [

77], and the homogeneity of the construct under examination (Equation (1)).

where

K = is the number of items,

= is the variance of the total score,

= is the variance of item.

SEM was employed to test and validate the proposed relationships using a multivariate approach, with SPSS version 26.0 and SmartPLS facilitating Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) [

78]. All measurement scales were assessed for reliability and construct validity through CFA. This method was chosen due to the number of factors and the relationships between factors and their corresponding measurement variables, as previously described [

79]. To evaluate whether the proposed model fits the empirical data, a structural model was developed to explore the hypothesized pathways (path model testing). Hypotheses were tested using multiple regression analysis, which examined the relationships between several independent variables and dependent variables, such as trust in e-government and its driving forces. The analysis also explored the varying relationships between trust and the use of e-government/e-government adoption. Multiple regression analysis provided valuable insights into the overall model, allowing researchers to assess whether adding variables improved the model’s predictive power [

80].

Given the complexity of the proposed model, SEM analysis was adopted to conduct validity analysis, model testing, and hypothesis testing. SEM has become one of the most widely used and suitable techniques in social sciences for advanced statistical analysis in recent decades. As noted by [

81], SEM is a multivariate technique that combines elements of factor analysis and regression, enabling researchers to simultaneously examine relationships between measured and latent variables (measurement theory) and between latent variables (structural theory). This approach allows for the analysis of unobservable variables indirectly measured through indicator variables (Equation (2)).

where

Y = e-government adoption (endogenous latent construct),

PEU = perceived ease of use,

TR = trust in e-government,

CE = citizen engagement,

M = media influence,

ε = error term.

The relationships between latent constructs, which are not directly measurable, were analyzed by categorizing SEM variables into two groups: endogenous and exogenous variables. A variable could simultaneously act as both a dependent and an independent variable. The equations captured all relationships between endogenous and exogenous variables, accounting for potential measurement errors in observed variables. SEM proved to have powerful ability to analyze complex models, revealing both direct and indirect relationships between variables [

82].

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Reliability Test

In order to assess the reliability of internal consistency between dimensions, authors usually compare the estimate of

with a conventional threshold set at 0.70 [

83], such that

> 0.70. The study employed 27 questions for the test, which shows high reliability (

= 0.710), exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.72 according to [

84], thus reinforcing the robustness of the measurements (

Table 1). This robust reliability indicates that the scale items are effectively aligned in measuring the intended construct. These results, in line with established norms and previous research, strengthen the credibility of the analyses on digital acculturation. The role of media in e-government adoption: the case of the region Rabat-Salé-Kénitra, Morocco. The distribution of the alpha coefficient confirms the strength of the internal consistency of the measures, reinforcing the validity of the data used in this study. Additionally, this study emphasizes the greater significance of the relationships between various independent variables (such as media, trust, digital services, complexity, compatibility, and observability) and the dependent variable (e-government adoption).

4.2. Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

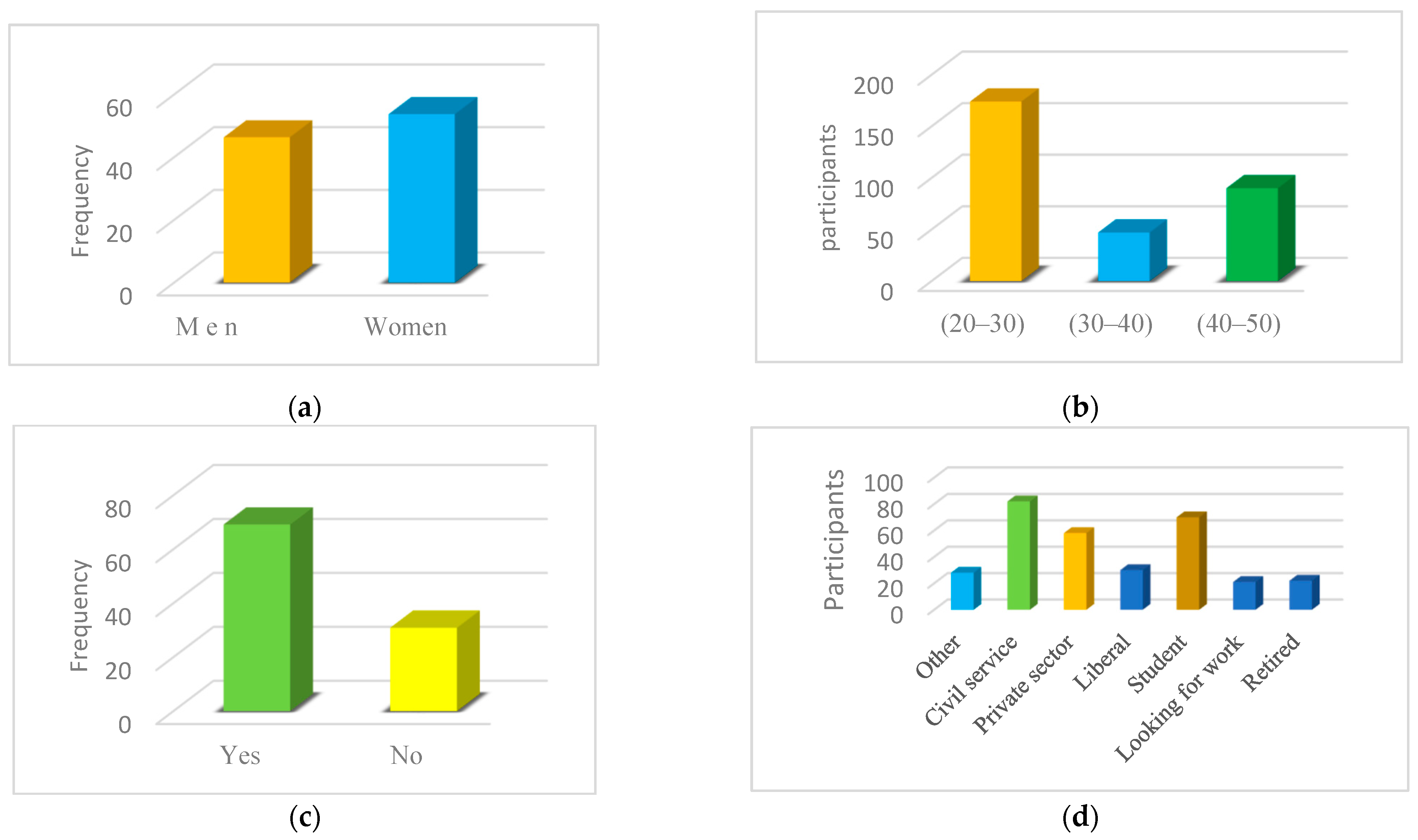

The data analysis was conducted using SPSS software (version 26). As summarized in

Table 2, descriptive statistics revealed that the sample comprised 311 participants, with a slightly higher representation of women 53.7% compared to men (46.3%). Regarding age distribution, the majority of respondents were between 20 and 30 years old (55.9%), followed by those aged 40–50 years (28.9%), while a smaller proportion fell into the 30–40 age group (15.1%). This indicates that the sample is predominantly composed of young adults, which may influence perspectives on employment, education, and digital engagement (

Table 2).

In terms of educational attainment, the vast majority of participants (88.1%) had completed higher education, while 11.9% had a high school diploma. This high proportion of highly educated individuals suggests that the sample may have higher levels of literacy and professional qualifications, which could impact responses related to career aspirations, workplace expectations, and professional mobility.

Employment status varied among participants, with the civil service sector being the most represented (26.4%), followed by students (22.5%) and individuals working in the private sector (18.7%). Other professional categories included liberal professions (9.6%), retirees (7.1%), and job seekers (6.8%), while 9.0% of respondents were categorized under “Other” occupations. The significant presence of public sector employees and students suggests a sample engaged in stable employment or higher education, which may influence perspectives on job security and career progression (see

Figure 2).

4.3. Frequency of Use of Digital Services

Descriptive statistics indicate that a majority of participants, 69.1%, reported having used digital public services to complete administrative procedures, while 30.9% had not. Regarding frequency of use, 67.2% of respondents engaged with these services once a month, 18.9% reported no usage, 9.6% used them more than twice a month, and 4.2% reported using them twice a month (

Table 3).

When asked to identify perceived benefits, the most commonly reported advantage was “easier access” (43.4%), followed by “time-saving” (23.2%) (

Table 3). A smaller proportion noted “no need to travel” (14.5%), while 18.9% of respondents indicated there were “no benefits.” This pattern suggests that while the majority acknowledge advantages such as enhanced accessibility and efficiency, a significant portion of the population remains skeptical about the overall benefits.

In terms of challenges, the most frequently cited obstacle was the need for “adequate digital skills” (67.8%), which points to a critical barrier to adoption. A smaller group (25.4%) reported experiencing “no problems at all,” suggesting that while challenges exist, they are not universal. Additional concerns included the perception of high costs (4.2%) and the lack of human interaction (2.6%), though these issues were less prevalent than concerns related to digital literacy (

Table 3).

4.4. Characteristics of Innovation

According to

Table 4, the analysis of innovation characteristics indicates that, in terms of adoption, 70.4% of participants reported engagement with the digital system, while 29.6% remained non-engaged. Attitudes toward digital transformation, were predominantly positive, with 88.7% of respondents affirming that digital transformation aligns with their cultural values and habits, reflecting a strong propensity for digital integration within the study population.

Self-assessed digital proficiency exhibited notable heterogeneity. Nearly half of the respondents (47.9%) identified as Level 3 users, denoting intermediate-to-advanced competency, while 20.9% classified themselves at Level 4, indicative of advanced digital skills. In contrast, 11.9% and 19.3% reported Level 1 and Level 2 proficiency, respectively, highlighting a segment of the population that may be at risk of digital exclusion due to limited skills. Technical challenges remain a significant concern, with 75.6% and 63.3% of participants (Q12 and Q13, respectively) acknowledging the experience of technical difficulties when utilizing digital services.

With respect to perceived benefits, the most frequently cited advantages included improved accessibility (34.1%), reduced necessity for physical travel (29.9%), and enhanced time efficiency (21.2%). Nevertheless, 10.3% of respondents reported no discernible benefits, and 4.5% identified cost reduction as a positive outcome. An evaluation of the usability of public service websites revealed that 45.3% of participants considered the platforms “relatively easy” to navigate, while 20.6% encountered difficulties, underscoring the need for ongoing improvements in user interface and experience.

Participants also articulated several recommendations for optimizing digital public services. The most prevalent suggestions included minimizing intrusive advertisements (41.5%), enhancing navigation features (29.9%), and improving the overall user interface (18.0%). Additionally, 10.6% advocated for the implementation of awareness campaigns, underscoring the importance of targeted communication strategies to foster greater engagement and digital literacy.

4.5. Characteristics of E-Government Users

The findings presented in

Table 5 provided valuable insights into participants’ engagement with digital tools, their proficiency levels, their confidence in usage, and the perceived necessity of digital features.

A significant majority of respondents (67.2%,

n = 209) indicated that the effective use of digital public services necessitates adequate digital skills, whereas 32.8% (

n = 102) did not perceive such competencies as essential. This finding highlights a broad acknowledgment of the importance of digital literacy within the study population. In terms of digital proficiency, this revealed that most participants possessed moderate to advanced capabilities, with 39.2% (

n = 122) identifying as Level 3 users and 35.0% (

n = 109) as Level 4 users. A smaller proportion (25.7%,

n = 80) classified themselves as Level 2 users, suggesting that while the majority are adept with digital technologies, a notable subset may experience difficulties with more complex digital tasks. Self-assessed confidence in utilizing digital tools (Q19) exhibited considerable variability. The majority (52.4%,

n = 163) reported moderate confidence, while 24.1% (

n = 75) expressed low confidence, and 4.5% (

n = 14) reported no confidence. In contrast, 15.8% (

n = 49) described themselves as confident, and only 3.2% (

n = 10) reported very high confidence in their digital abilities. These results indicate that, although most participants demonstrate a reasonable degree of confidence, a substantial proportion may benefit from targeted training or support to further enhance their digital competencies. (

Table 5)

Regarding the perceived necessity of digital characteristics, the majority of participants (72.99%, n = 227) deemed the digital tool or service to be essential, underscoring its relevance in their daily routines. In contrast, 27.01% (n = 84) did not perceive the feature as necessary, indicating potential areas for improvement or the reconsideration of user needs and preferences.

4.6. Mediating Variable: The Media

Table 6 presents a detailed analysis of participants’ awareness, perceptions, and future intentions regarding digital public services. In terms of initial exposure (Q21), nearly half of respondents (48.9%) identified mass media as their primary source of information, while social networks accounted for 27.0% (

n = 84), and word of mouth for 24.1% (

n = 75). These findings underscore the pivotal role of both formal and informal communication channels in promoting the adoption of digital tools. Regarding the perceived influence of television advertisements (Q22), 66.2% of participants acknowledged their role in encouraging the use of e-government services, whereas 33.8% did not perceive such an effect. Despite the generally positive reception, a significant proportion of users expressed dissatisfaction, highlighting the need for ongoing improvements in user experience and functionality.

Perceptions of the utility of television advertisements (Q23) were notably divided: 41.5% of respondents considered them completely useless, 31.8% deemed them essential, and 26.7% rated them as very useful. This pronounced divergence in evaluations suggests that the effectiveness of such promotional efforts may vary considerably across user segments, emphasizing the importance of tailoring communication strategies to diverse audience needs. An assessment of the image conveyed by television advertisements (Q24) also revealed mixed opinions: 35.4% rated the portrayal of security, effectiveness, and reliability as excellent, 17.7% as good, and 46.9% as poor. These contrasting assessments highlight the necessity for continuous quality improvements, particularly in addressing the concerns of those who perceive the messaging as inadequate.

With respect to trust in e-government services (Q25), an overwhelming majority (86.2%) indicated that television advertisements increased their level of trust, while 13.8% did not share this sentiment. This robust inclination toward continued engagement is further reflected in future usage intentions (Q26), with 55.9% of respondents expressing certainty about using e-government services for future administrative procedures. However, 17.4% considered future use unlikely, and 26.7% deemed it impossible, indicating that barriers to sustained engagement persist for a notable subset of users.

When asked about their willingness to recommend e-government services to others (Q27), 35.4% were confident in broader adoption, while 28.0% viewed it as unlikely, and 36.7% considered it impossible. These mixed projections suggest that, although optimism exists regarding the potential for widespread adoption, skepticism remains prevalent among a significant portion of the population (

Table 6).

4.7. Measurement Model

The structural model was evaluated using the PLS-SEM approach. PLS-SEM is particularly useful for validating models that are both complex and have not been extensively tested in prior literature [

85]. Moreover, this approach accounts for measurement error, yielding results that are generally more precise than traditional regression techniques [

86]. Given the need for accurate estimations and the complexity of the modified UMEGA model, an area that remains unexplored in existing research, the PLS-SEM approach was deemed the most appropriate. SMART PLS 4.0 was selected as the analytical tool due to its extensive validation in studies involving model evaluation [

87]. Compared to alternative approaches such as AMOS and LISREL, which are primarily used for confirmatory testing [

88], SMART PLS offers enhanced capabilities for assessing total indirect effects. This feature is particularly critical in the present study, as it facilitates an in-depth examination of the media’s role in e-government adoption through the attitude hypothesis and provides insights into the cumulative indirect effects of all incorporated variables.

To ensure the reliability and validity of the proposed model, multiple quality assessment criteria were employed, as detailed in

Table 7 and

Table 8.

Table 7 presents key reliability and validity metrics, including the composite reliability (CR), Cronbach’s α, average variance extracted (AVE), and factor loadings. Factor loadings above 0.7 are generally considered indicative of construct reliability [

83]. As shown in

Table 7, the factor loadings in this study ranged from 0.702 to 0.944, meeting the recommended threshold. Furthermore, no cross-loading issues were observed, as all items loaded substantially higher on their intended constructs, confirming that none of the indicators were erroneously assigned to an incorrect factor.

Construct reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s α and composite reliability. A Cronbach’s α value of at least 0.7 is generally required to establish internal consistency [

89]. This criterion was met with α values ranging from 0.698 to 0.742. Similarly, composite reliability values should ideally exceed 0.8, though values above 0.6 are considered acceptable [

90]. In this study, all composite reliability values were above 0.8, ranging from 0.789 to 0.981, with the exception of compatibility and digital services (

Table 7), thereby confirming the construct reliability of the factors.

In addition, converging validity was evaluated using the AVE, with a threshold of 0.5 indicating adequate construct validity [

91]. As reported in

Table 7, AVE values ranged from 0.511 to 0.576, satisfying this requirement. Discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion (

Table 8), which states that a construct demonstrates discriminant validity if the square root of its AVE (

Table 8) is greater than its correlations with any other latent construct [

90]. As observed in

Table 8, all diagonal values (square roots of AVE) were higher than the corresponding off-diagonal values, confirming the discriminant validity of the scales used. Following prior research recommendations [

91], these results affirm the reliability and validity of the measurement model, ensuring robustness in subsequent structural model assessments.

Finally, to minimize potential concerns related to common method bias, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted on the dataset. Following the approach outlined by [

92], an exploratory factor analysis was performed, extracting an unrotated solution using SPSS version 26.0.

The analysis revealed that the extracted factors collectively explained 67.9% of the total variance, with the highest variance attributed to a single factor reaching only 22.8%. Notably, no single factor accounted for more than 50% of the variance, indicating that common method bias was unlikely to pose a threat to the study’s validity. These results further support the robustness of the measurement model.

4.8. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

Figure 3 and

Table 9 summarize the statistical outcomes of the structural model tested in this study. The model demonstrated strong explanatory power, accounting for 67.9% of the variance in the factors influencing potential users’ adoption of the “e-government” application, a result considered high according to [

93].

As indicated in

Table 9, all hypotheses were statistically significant at the 0.05 level, except for the path between perceived compatibility and the media, which was not supported by the data. Also, previous studies have highlighted the significant role of media in facilitating digitalization and e-government adoption. For instance, [

94] demonstrated that compatibility and trustworthiness are strong predictors of citizens’ intentions to use e-government services. Similarly, [

95] reported comparable findings, showing that compatibility is a key factor in modeling citizen satisfaction with the mandatory adoption of e-government, particularly when influenced by media channels. Specifically, trust (Tr) was identified as a critical determinant in e-government use, with a significant path coefficient of 0.801. This was corroborated by a t-value of 22.97, which exceeds the critical threshold of 1.96, validating the acceptance of the primary hypothesis. Moreover, the study revealed that behavioral intentions explained 67.9% of the variance in potential users’ trust in adopting the “e-gov” application. A moderate proportion, approximately 32.5%, of the variance in actual trust was attributable to factors not included in the model.

The findings further emphasize the significant roles of digitalization (H2: β = 0.419; t = 4.063) and media (H3: β = 0.421; t = 4.151) in shaping behavioral trust, in line with the theoretical framework. The coefficients for both digitalization and media were similar, highlighting their substantial impact on predicting users’ behavioral intentions toward the adoption of the “e-gov” application. The analysis revealed that “e-gov” adoption and media accounted for 65.1% of the variance in trust, reflecting their considerable influence on users’ attitudes and behaviors.

The study also established that relative advantages (H5: β = 0.295; t = 3.016) and compatibility (H7: β = 0.244; t = 3.089) were significant, suggesting that these factors positively influence the media’s role in “e-gov” adoption. Conversely, complexity exhibited a negative relationship with the media’s influence (H8: β = −0.163; t = 2.902), implying that higher complexity diminishes user acceptance of e-government applications due to perceived reduced benefits. Furthermore, observability was found to be statistically significant (H11: β = 0.420; t = 4.113), suggesting that greater visibility of the outcomes and the benefits of using the “e-gov” application increase the likelihood of adoption. Collectively, relative advantages, compatibility, and observability explained 67.6% of the variance in perceived benefits of use.

Relative advantages (H4: β = 0.189; t = 2.420) and observability (H11: β = 0.594; t = 5.012) also had a significant positive effect on e-gov use. In contrast, complexity negatively influenced the digitalization of use (H9: β = −0.123; t = 2.854), supporting the notion that higher complexity reduces users’ willingness to adopt public services. Interestingly, compatibility did not show a statistically significant effect (H6: β = 0.167; t = 1.436) in this study.

Relative advantages, compatibility, and observability together explained 67.6% of the variations in the perceived ease of use of the “e-gov” application, as assessed by potential users. Additionally, the study found that 72.86% of respondents expressed a willingness to use the “e-gov” adoption in the future, representing a notably high adoption rate. In contrast, only 11.45% of respondents indicated no intention to use “e-gov”, and 15.69% remained undecided regarding future adoption. These findings provide valuable insights into the potential trajectory of e-government adoption, despite its currently limited uptake.

4.9. Model Quality Indicators: R2 and Predictive Relevance (Q2)

The quality of the model was assessed using two key indicators: The R

2 and Q

2. The R

2 coefficient is commonly used to evaluate the explanatory power of the model, reflecting the extent to which independent variables account for the variance in the dependent variables. As detailed in

Table 10, the overall R

2 value for the model was 65.7%, indicating that a substantial portion of the variance in the dependent variables was explained by the independent variables. Specifically, the digitalization of use and perceived benefits accounted for 68.4% of the variance in trust toward the adoption of the “e-gov” application. Moreover, relative advantages, compatibility, complexity, and observability explained 68.4% of the variance in perceived ease of use, while 67.6% of the variance in the role of media in the adoption process was explained.

These results demonstrate that the model possesses robust explanatory power, effectively accounting for the variance in the internal variables, in line with the criteria established by [

93]. In addition, the Q

2 was assessed to evaluate the model’s ability to predict new data based on the empirical findings. Q

2 is computed via cross-validation, with values greater than zero indicating that the model has predictive relevance. Conversely, Q

2 values of zero or lower suggest a lack of predictive relevance. The results, as presented in

Table 10, confirm the predictive relevance of the proposed model, with all Q

2 values exceeding zero. This further supports the model’s ability to predict outcomes, as per the guidelines of [

96].

5. Conclusions

Digital Transformation has emerged as a fundamental driver of Morocco’s economic and social development, offering immense potential to enhance public service delivery, improve administrative efficiency, and stimulate economic growth. Within this framework, e-government plays a pivotal role in the digital transition, enabling greater accessibility to public services, improving their quality, and fostering trust between citizens and public administration. The COVID-19 pandemic has further accelerated the digitalization of public administration, underscoring the need to simplify processes and enhance interconnectivity between public institutions to better serve citizens.

Despite these advancements, Morocco continues to face significant challenges in its digital transformation journey. The persistent “digital divide,” driven by factors such as illiteracy, lack of trust, and limited media engagement has hindered the adoption of e-government services and contributed to a decline in the country’s international rankings. These challenges highlight the urgent need for a robust, integrated digital infrastructure to support the effective implementation of e-government initiatives.

This study examined the role of media as a demand-side determinant of e-government adoption in the Rabat–Salé–kénitra region. Employing a rigorously designed survey instrument comprising 27 items across five thematic sections, the analysis produced a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.710, confirming strong internal consistency. Statistical analyses, including the chi-square (χ2) test with values ranging from 231.26 to 855.02 and a p-value of 0.000, demonstrated a significant relationship between media and e-government adoption. Furthermore, ANOVA results, with a p-value below 0.000, revealed significant relationships between media exposure and adoption behavior, underscoring the influence of information channels in shaping citizens’ perceptions and engagement with e-government services.

These findings carry important implications for policy and practice. By strategically leveraging the media to build trust, enhance usability perceptions, and address informational gaps, policymakers can narrow the digital divide and foster sustained citizen engagement with e-government services. While the empirical focus is on the Rabat–Salé–kénitra region, the patterns observed resonate with broader dynamics in Morocco and, by extension, other developing-country contexts.

Crucially, this research addresses a documented gap in the literature: whereas most prior studies privilege the supply-side perspective, our work foregrounds the demand-side factors trust, perceived usability, and media influence in a developing-country setting. This orientation enriches prevailing theoretical and empirical understandings by illuminating the behavioral and perceptual dimensions underpinning adoption decisions.

Although grounded in the Moroccan experience, the conceptual model and relationships identified may be relevant in diverse socio-economic contexts, including advanced economies. Nevertheless, variations in institutional maturity, governance cultures, and citizen expectations warrant careful contextualization before extrapolation. Future research should therefore replicate and refine this framework across heterogeneous settings to assess its generalizability and extend its theoretical reach.

Ultimately, advancing e-government adoption in Morocco demands an integrated strategy that combines technological innovation with social and institutional capacity-building. Only through such a multidimensional approach can digital transformation serve as a sustainable driver of development and democratic governance.