Abstract

This study evaluated the psychometric properties of the Digital Citizenship Scale in Chilean university students, specifically the factorial structure and its reliability, construct validity, and factorial invariance by sex were analyzed. The sample consisted of 905 students whose average age was 22 years, of which 59.7% were women. The methods used were Exploratory Factor Analysis and Confirmatory Factor Analysis. The result of the exploratory analysis suggested retaining the 26 items of the original scale grouped into five factors. The results of the confirmatory analysis corroborated the original structure of the scale and specified a model of five correlated factors. The reliability analysis indicated a total ordinal alpha of 0.87. The measurement invariance analysis showed that the degree of equivalence of the instrument by sex was plausible at a strict level. The scale provides guidance for institutional decision-making regarding initiatives focused on digital inclusion and participation. It was concluded that the Digital Citizenship Scale presents adequate psychometric properties for its use in Chilean university students.

1. Introduction

From studying to voting in elections, the Internet is becoming increasingly present in people’s lives. The proliferation of technology has coincided with the category of citizenship and the exercise of rights in recent years [1,2]. Today, two out of every three people in the world access the Internet, including 5.4 billion social media profiles [3]. In the case of Chile, the Internet reaches 67.4% of the country’s households and 22.8 million mobile users [4], consolidating a sustained increase in the last decade.

Along with this expansion, the Internet has also facilitated the emergence of new methods for exercising rights. This is primarily due to the transformation of social interactions increasingly immersed in the digital space [5,6,7] and, specifically, to an expanded repertoire of forms of Internet-mediated participation [8,9]. Thus, Digital Citizenship emerges as a concept of study defined as the ability to participate fully, critically, and actively in social, political, and economic life through the use of digital technologies [10,11,12,13]. Also, Digital Citizenship emerges as a framework for analyzing the reproduction of multiple dimensions of traditional inequalities and exclusions in digital spaces [14,15,16,17,18]. In this line of ideas, the present study evaluates the psychometric properties of the Digital Citizenship Scale [11] in university students in Chile, in order to have a valid psychometric instrument to investigate digital participation, especially among university students in Chile.

This work includes a cohort of university students in Chile who were still in high school in October 2019 when they evaded paying the Santiago subway fare in protest of a fare increase. From the act of evasion, young Chileans opened a range of possibilities and demands to the established political, economic, and social model [19]. This process found a new space on the Internet for organization and political participation, especially through #Chiledespertó [20]. A year later, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the generation that began the Chilean social uprising went to university at a key moment when educational communities globally had to accelerate their digitization processes [21]. In 2020, university students continued to adapt the forms of political action they inherited from the tradition of student demonstrations in Chile [22], this time considering digital media not as a supplementary tool, but as the sole alternative.

Specifically, the Chilean public university has contributed to disseminating an elitist social status in Chile, resulting in a student movement. Historically, this group has focused its arguments on more consolidated aspects of the Chilean political system, specifically the privatization of education, which was devised by the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. Therefore, the relevance of studying citizenship practices, especially digital ones among university students, is reflected in the figure of the public university as a key actor in the demand for a new relationship between society and the Chilean state.

Digital Citizenship Conceptualizations and Measures

There are currently two systematic reviews that provide an overview of the Digital Citizenship construct, including its development and various nuances based on the supporting theoretical paradigms. On the one hand, there was Chen et al. [10], who analyzed 450 publications between 2010 and 2018, and then Shi et al. [14], who analyzed 440 between 2010 and 2020. Both studies found two solid conceptual lines. The Ribble [23] line places the focus of the concept on competencies and behavioral norms when using digital media to interact socially. On the other hand, there was Mossberger et al. [16] who focused on Internet-mediated social and political participation.

As a theoretical paradigm of citizenship, Mossberger’s line takes up the deliberative democracy model proposed by Habermas [24], which approaches it as exercising rights based on ethical and emancipatory principles. This concept regards citizenship education as an overarching element that permeates individuals’ education and cannot be limited to merely acquiring knowledge about their rights or engaging in civic education [25]. The sociopolitical theory of Jürgen Habermas conceives schools as key elements of civil society, where education for citizenship is based on values such as emancipation, free dialogue, and democratic and active engagement in the community [26].

Various studies have appeared that focus on the educational field in relation to Digital Citizenship, based on the knowledge derived from the deliberative democracy paradigm [25,27,28]. These studies highlight places of education [29,30,31], particularly universities as spaces for social discussion [32] and reflection on more participatory and democratic public decision-making mediated by the Internet [12,33,34].

In referring to Digital Citizenship research and measurement, Shi et al. [14] found in a systematic review of measurement instruments that the most widely used and proven instrument is the Digital Citizenship Scale (DCS) developed by Choi et al. [11]. In addition, it was found that this scale presents the most exhaustive design and validation procedures and one of the few that contemplates practices from a perspective of Internet-mediated civic and political participation [14].

The DCS [11] is composed of five factors, Technical Skills, Networking Agency, Critical Perspective, Local/Global Awareness, and Internet Political Activism, and was originally developed in English for application to university students in Ohio. Since its publication, it has been translated, adapted, and validated in countries such as Spain [35], Mexico [36], Turkey [37,38], and South Korea [34], presenting adequate evidence of reliability and validity in every case. In the case of Chile, there is no evidence that this scale has been previously adapted and validated, nor has any other instrument been found to measure Digital Citizenship practices.

Thus, the present study seeks to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Digital Citizenship Scale [11] in university students in Chile. Specifically, the adaptation of the scale for the Mexican university population [36] will be used, as it is the only adaptation in Latin America and has adequate evidence of reliability and validity. This adaptation in a Mexican population, in turn, comes from the translation and validation made by Lozano-Díaz and Fernández-Prados [35] for university students in Spain. In this sense, having an adapted and validated tool in Chile that shows scientific evidence of the reliability and validity of an instrument would provide universities with a key instrument to guide and make decisions in the design of initiatives associated with the digital participation and inclusion of university students.

2. Methods

The present study is part of the research on instruments, which aims to design, adapt, and validate measurement strategies. In this case, a cross-sectional design with a quantitative approach was used to account for the main objective. In particular, structural equation modeling was performed to evaluate the proposed measurement model by applying a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA).

2.1. Participants

The study participants were determined through non-probability sampling, including students from the country’s four macro-zones: North, Central, South, and Austral South. The inclusion criterion was to be a student enrolled in an undergraduate program at a state university in Chile. The sample consisted of 905 university students from 7 Chilean state universities. The participants’ average age was 22 years and came from different fields of study, with social sciences predominating. Table 1 shows the participants’ characteristics. Technically, the sample size fulfills the conditions required to perform factor analyses [39,40,41].

Table 1.

Characterization of participants.

2.2. Procedure

Prior to data collection, a team of experts in participation, citizenship, and ethnic identity, composed of researchers from Chile and Mexico, carried out the process of linguistic adaptation of the scale. At the qualitative level, a pilot application of the first adaptation was made to 15 Chilean students who met the inclusion criteria of the study sample, and after answering the questionnaire, a discussion group was held to raise their comments and observations regarding the questionnaire. From these instances, the idea of making minimal adaptations to some items arose. The modifications consisted of changing the word “computadoras” for “computadores” and the word “laptops” for “notebooks” in items 3 and 4. Additionally, in item 4, the last sentence, “…to achieve the objectives I pursue”, was changed to “…to achieve the objectives I set for myself”. These minor modifications followed Muñiz et al. [42] protocols and criteria for adapting scales from one culture to another.

Once the instrument was adapted, we contacted the authorities of the state universities with the largest number of students in the country’s four macro-zones: North, Central, South, and Austral South. The research team presented the project to arrange the signing of a letter of commitment in which the universities agreed to allow the dissemination of the project among their students. After two months of online meetings with different university authorities, seven state universities agreed to participate in the study. The research team prioritized the participation of universities with the largest student enrollments in each region to obtain as many participants as possible and ensure variability among them.

The instrument was disseminated through the institutional e-mails of students at the participating universities to collect data. The dissemination was complemented via social media through the official Instagram accounts of the participating universities. Students accessed the questionnaire via the Questionpro platform. On the platform, they signed an informed consent form, which was approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of the Universidad de La Frontera (protocol code 140_23 and approved on 22 September 2023). The instrument was presented, and their participation was explained. The ethical criteria of the study were safeguarded, guaranteeing anonymity and the non-individualization of their responses. The average time it took to answer the instrument was 14 min. Data were collected between May and November 2024, and once completed, the psychometric properties and factorial invariance of the Digital Citizenship Scale were analyzed.

2.3. Instruments

2.3.1. Social Characterization Questionnaire

The social characterization questionnaire included questions on the sociodemographic variables of the participants. Questions such as sex, belonging to indigenous peoples, socioeconomic level, area of study, residence (urban/rural), and Internet access were included.

2.3.2. Digital Citizenship Scale

The Digital Citizenship Scale [11] measures young adults’ skills, perceptions, and levels of participation in Internet-based communities. For this study, the Mexican version [36] was used, adapted to the context of university students. The instrument is composed of 26 items distributed in 5 factors: Internet Political Activism (9 items), Technical Skills (5 items), Local/Global Awareness (3 items), Critical Perspective (4 items), and Networking Agency (5 items). Response options are provided on a Likert-type scale with a 5-point response range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). To interpret the results, scores are considered for the 5 factors or subscales and the total scale.

Concerning Critical Perspective, participation in society and perception of the Internet is measured, including items such as “I believe that participation on the Internet promotes engagement in real life”, “I believe that participation on the Internet is a good way to change something I think is unfair”, or “I believe that participation on the Internet is an effective way to get involved in political or social issues”. These elements come partly from Feenberg’s critical theory of technology [43] and Castells’ ideas [5] of flow space and timeless time in the information age.

In relation to Technical Skills, people’s abilities to access the Internet, use digital technologies, find information, and download applications are measured. Included are statements such as the following: “I can use the Internet to find the information I need”, “I can use the Internet to find and download applications that are useful for me”, or “I can use digital technologies (e.g., cell phones, tablets, computers, etc.) to achieve the goals I set for myself”. This factor is associated with skills and media literacy and is linked to digital participation.

Networking Agency measures individuals’ highest level of Internet activities and technical skills focused on communication, collaboration, and publication. This subscale includes items such as “I comment on other people’s writings on news websites, blogs, or social media that I visit”, “I may regularly post thoughts related to political or social issues on the Internet”, or “I like to collaborate with others via the Internet more than I do in real life”.

Local/Global Awareness measures individual awareness of social and political issues at the local, national, and global levels. It includes items such as “I am more aware of global issues through the use of the Internet” or “I think the Internet reflects the biases and dominance of real-life power structures”. This factor is associated with possible affiliations and local representations of global movements, e.g., #metoo or #blacklivesmatter.

Internet Political Activism measures an individual’s political participation on the Internet through unconventional political actions or what has come to be called cyberactivism [12]. It includes items such as “I belong to groups on the Internet that are involved in political or social issues”, “I collaborate with others on the Internet to solve local, national, or global problems”, or “I perform volunteer activities for an organization of a social or political nature on the Internet”. The scores on this subscale are related to people’s commitment and direct political involvement through digital media.

2.4. Data Analysis Plan

After the data collection, a matrix containing the participants’ responses was created. The SPSS v22 software was used to sort and filter the data to keep only the complete responses. The database comprised 905 responses and was subsequently divided into two equal parts, with estimation and validation subsamples [44]. In this case, despite having evidence of the factor structure of the scale, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was performed since previous studies that evaluated the psychometric properties of the instrument have presented different factor structures, with items being assigned to various factors [11,36,37]. Accordingly, an EFA was performed with the estimation sample and a CFA with the validation subsample [45]. The database was divided using the Solomon method, which optimally divides the sample into two equivalent halves and guarantees the representativity of the subsamples [46]. For the estimation sample (n = 453), Horn’s parallel analysis and an EFA were performed [47]. For the validation sample (n = 452), a CFA was performed to test the factor structure of the DCS. The factor structures included were the following: (1) the DCS Mexican version [36]; (2) the DCS Spanish version [35]; (3) the DCS original version [11]; and (4) the resulting factor structure of the EFA. The factor structures evaluated coincide in the number of factors but not in the distribution of the items.

The CFA was performed with the R programming language [48] using the Lavaan package [49] and applied to the polychoric correlation matrix [50]. The model parameters were estimated using the unweighted least squares method [44]. Regarding fit indicators, the literature on CFA and SEM suggests cut-off points to guide applied research in deciding which models should be rejected and which can be retained. In general, models with CFI ≥ 0.95, TLI ≥ 0.95, RMSEA ≤ 0.08, and SRMR ≤ 0.10 are considered to have an acceptable fit [51,52,53]. For the reliability analysis of the scale, the internal consistency method was considered with the omega coefficient (ω), with values greater than 0.70 being deemed acceptable for the total scale and its dimensions [54].

For comparisons between participants to be valid, the concepts of interest must be comparable, i.e., invariant or equivalent, across groups. Therefore, once the factor structure with the best fit indicators was confirmed, the degree of measurement invariance for the sex variable was evaluated. The sex variable was taken as a criterion, as it is a key characteristic according to segregation and the digital divide [55,56,57]. The hierarchy to calculate the measurement invariance considered three levels: (1) configural, which considers equality in the number of factors and equal distribution of items in the groups; (2) metric, which considers equality in factor loadings; and (3) scalar, which considers equality in item means [58,59]. This is relevant because the validity and reliability of the instruments are properties adapted according to the context in a dynamic process that must be ensured in each study [60]. For the measurement invariance analysis, a set of criteria was evaluated, consisting of the difference of CFI < 0.010, RMSEA < 0.015, or SRMR < 0.030 [61]. Finally, hypothesis tests were performed using the Mann–Whitney U statistic to compare the participants’ scores according to sex and the Spearman correlation test to analyze the relationship between age and Digital Citizenship.

3. Results

3.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

The results of Horn’s parallel analysis suggested a five-factor structure with true eigenvalues higher than the random eigenvalues. The model fit indices indicated the feasibility of performing a factor analysis: KMO test (0.90); Bartlett’s test of sphericity (χ2 [gl = 325] = 9312; p < 0.001); and goodness-of-fit index (GFI = 0.99). With respect to the factor structure of the instrument, there were five correlated factors, which collectively accounted for 65% of the construct validity. This structure coincides with the theoretical proposal of five factors [11,35,36]. The factor loadings of the items ranged between 0.40 and 0.90 (see Table 2), adequate values that suggest retaining the totality of the items [62]. The EFA results show that items 1 to 6 are grouped in the Technical Skills (TS) and items 7 to 10 correspond to Networking Agency (NA). The results of these two factors coincide with the structure of the Spanish version. Items 11, 16, and 17 are grouped in Critical Perspective (CP), and items 12, 13, 14, and 15 belong to Local/Global Awareness (LGA). In the two previous factors, there is a difference in terms of the relevance of the items with earlier versions of the scale presenting item 12, “I think I can rethink my beliefs about a particular topic when I use the Internet”, as associated with the Local/Global Awareness construct. Finally, items 18 to 26 were grouped under the Internet Policy Actions (IPA), which coincides with the Spanish and Mexican versions of the scale. As for the distribution of the items, this result differs from the Spanish version of the scale: Item 12 is associated with Local/Global Awareness, whereas in the Spanish version, it is associated with the Critical Perspective. On the other hand, with the Mexican version, the results of the EFA present two differences: the one described above regarding item 12 being part of Local/Global Awareness, and item 6, “I like communicating with other people through the Internet” being in Technical Skills, which in the Mexican version is associated with Networking Agency. Table 2 presents the factor loadings of each item according to the factors identified.

Table 2.

Factor loadings of the Digital Citizenship Scale.

In order to trace the evolution of the factor structure of the Digital Citizenship Scale, Table 3 shows the items for each factor in the Spanish and Mexican versions, and the results of the EFA in the Chilean university population. The table shows the variations in terms of the items belonging to each factor. It is noteworthy that the Local/Global Awareness factor is the only one that grows in terms of the number of associated items, following the trend from the original version that only contemplated two items for this factor.

Table 3.

Evolution of the factor structure of the DCS in Spanish.

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Using the CFA, the factor structures proposed in different versions of the scale were evaluated. This procedure was performed with the validation subsample composed of 452 cases. The measurement models evaluated were the original Digital Citizenship Scale [11], the version with adolescents in Spain [35], the version for students in Mexico [36], and the structure proposed by the EFA. As illustrated in Table 4, the analysis results show that the models with the best fit indicators are the Spanish version by Lozano-Díaz and Fernández-Prados [35] and the version resulting from the EFA. The latter is the one with the slightly better results.

Table 4.

Confirmatory factor analysis results.

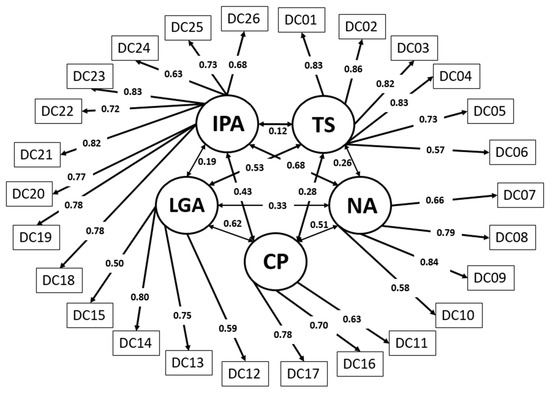

Figure 1 shows the factor loadings resulting from the CFA. This result includes the measurement model resulting from the EFA. The loadings vary between 0.50 and 0.86. In addition, the relationships between the associated factors are displayed.

Figure 1.

Standardized estimated parameters of the DCS model with five correlated factors.

3.3. Instrument Reliability Analysis

Due to the ordinal nature of the data, the ordinal alpha statistic [54] was considered for the reliability analysis of the scale. The results indicated values above 0.7 for all factors and 0.87 for the entire scale. These results are considered adequate according to the cut-off points proposed in the specialized literature. Table 5 presents the results in detail.

Table 5.

Reliability indices of the Digital Citizenship Scale for Chilean university students.

3.4. Measurement Invariance Analysis of the Instrument

The invariance analysis began by evaluating the goodness of fit of the five-factor model of the scale for Chilean university students in both sample groups (men/women), showing that the goodness-of-fit indices were satisfactory (χ2 S-B = 2130 (578); CFI = 0.969; SRMR = 0.083; and RMSEA = 0.077). This confirms that the factor structure, with the same items, remains stable in men and women. This model was considered a reference for the following restrictions. Table 6 shows no statistically significant differences in the χ2 S-B (gl) index between the configural and metric invariance degree. As shown in Table 6, the differences in CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR of each of the degrees of invariance (metric, scalar, and strict) compared to the level of configural invariance are minimal and lower than the change criteria suggested by Cheung and Rensvold [63] and Chen [61]. This suggests that the DCS for Chilean university students reaches a strict invariance level, maintaining its factor structure while differentiating between the sexes and enabling sex-based comparisons of the scores [51].

Table 6.

Fit indicator models according to levels of invariance for variable sex.

3.5. Comparisons of the Digital Citizenship Scale Among University Students in Chile According to Sex and Age

After confirming the violation of the assumption of normality of the data, the Mann–Whitney U test was performed to compare the scores obtained by the study participants. Statistically significant sex differences are reported on the total DCS scores and the factors of Networking Agency, Critical Perspective, and Internet Political Activism. The women obtained higher values than the men. Table 7 shows the contrast statistics according to sex, mean scores, and standard deviation.

Table 7.

Mann–Whitney U test results for DCS scores according to sex.

The results of the spearman correlation analysis showed that the age of the participants and the Digital Citizenship Scale present statistically significant relationships but only for the case of men, specifically, in the factors of Networking Agency and Internet Political Activism. These relationships in both cases were positive, i.e., the older the age of the participants, the higher the scores on Internet Political Activism and Networking agency reported. Table 8 shows the results for all the factors of the scale according to gender.

Table 8.

Spearman correlations between Digital Citizenship Scale and participants’ age.

4. Discussion

Research on digital participation through the idea of citizenship has become relevant in recent years given the reconfiguration of social interactions [5,6,7], particularly among generations born after the widespread use of the Internet [64]. Therefore, university students in Chile, digital natives, have become a generation that inherited the mechanisms of social and political participation from a long tradition of student movements [22] but, at the same time, have shifted towards a new logic of citizenship and participation [65,66]. This transition has become more complex as the Internet has become a space to reproduce the inequalities and exclusions in today’s societies [67].

It is in this context that the concept of digital citizenship becomes key from a Critical Perspective [68], participatory and social justice [16], especially in universities [12,33,34] as spaces for social discussion [32].

The main objective of the present study was to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Digital Citizenship Scale in university students in Chile. This instrument was originally developed by Choi et al. [11], translated into Spanish by Lozano-Díaz and Fernández-Prados [35], and adapted for Mexican university students by Galván et al. [36]. The results obtained in the EFA coincide with the five-dimensional factor structure proposed by previous scale versions. However, there is a difference in the distribution of the items in the case of Local/Global Awareness. This factor in the original 2017 proposal consisted of two items, and then the Spanish version presented empirical evidence that the item “I think the Internet reflects the prejudices and dominance of real-life power structures” was associated as a third item in Local/Global Awareness. The results of the EFA performed in the present study suggest considering, in addition, the item “I find that I can rethink my beliefs regarding a particular topic when I use the Internet” as part of Local/Global Awareness. This proliferation of ideas associated with the global context is related to the awareness of issues that cross borders and become global movements [69], for example, #blacklivesmatter, #NiunaMenos, #Metoo, among many other cyberactivist experiences [70].

The measurement model for the psychometric scale, as assessed from the CFA, meets the criteria established by the specialized literature. The reliability analysis of the scale also indicates satisfactory results, with ordinal alpha values over 0.70.

Measurement invariance for the DCS was evaluated on three levels, taking the key variable sex into account to ensure that the scores were comparable between men and women. The levels of invariance evaluated were the following: (1) factor structure (configural invariance), (2) factor loadings (metric invariance), (3) item means (scalar invariance), and (4) invariant residuals (strict invariance) between men and women. The results showed that the scale presents an invariant factor structure between groups and coincides with the theoretical model of five correlated factors.

When analyzing the participants’ characteristics and the scale scores, in general terms, the students state they have access to the Internet either at home or on their cell phones. It was also noted that this access is not recent since, on average, the study participants have been accessing the network for 10.7 years. One notable discovery is that the study population has acquired a greater proficiency in digital skills while engaging in fewer digital participation practices. From the digital citizenship point of view, this finding poses a challenge to advance how the Internet is presented to students, i.e., at the skills level, there is evidence of their development. At the same time, the scores are lower in practices associated with Political Activism, Networking Agency, or Critical Perspective. In this sense, the study’s main contribution is that it focuses on a quantitative measurement instrument, thereby obtaining results solely from this perspective. This is a limitation because the instrument does not investigate qualitative dimensions of the Digital Citizenship construct. It is recommended that the scale be complemented by incorporating research strategies that focus on the skills and attitudes students need to use the Internet and the significance, meanings, and evaluations they assign to the individual and/or collective outcomes attained through digital platforms. For example, following the research line of Allaste and Cairns [71,72], who have opted for qualitative strategies to investigate the meanings associated with political participation and Digital Citizenship.

Another limitation of the study is that a large percentage of the sample is concentrated in the social sciences, so it is recommended to take this into account when applying the instrument to university students from other areas of study. Additionally, it is suggested to carry out a review and adaptation to apply this scale in students of private universities in Chile; especially taking into account that in instrumental terms, the adaptation and validation of psychometric scales that include topics associated with politics and social power relations are conditioned to moral and ethical criteria of the cultural and socioeconomic contexts in which they are applied.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this paper provides empirical evidence with a scientific basis of the adequate validity, reliability, and measurement invariance according to sex of the Digital Citizenship Scale among university students in Chile. Having an instrument of this type for the Chilean population makes it possible to bolster applied research on digital participation in Latin America, especially in universities, as well as strengthen the concept of Digital Citizenship from the critical and participatory perspective associated with social justice [11,12,16,68]. Applying the Digital Citizenship Scale in the university setting will provide useful data regarding e-participation. These data will be employed to develop policies aimed at promoting digital inclusion, enhancing political engagement through digital media, and fostering local and global awareness among university students in Chile. Specifically, novel forms of political and citizen mobilization are emerging in response to institutionalism and conventional governance processes, as well as the reevaluation of democracy and the concept of public space.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G.-C. and J.T.-A.; methodology, M.G.-C. and C.B.-O.; software, M.G.-C.; validation, M.G.-C., J.T.-A., S.H.-O. and P.L.-R.; formal analysis, M.G.-C.; investigation, M.G.-C., J.T.-A. and I.N.-S.; resources, M.G.-C. and J.T.-A.; data curation, M.G.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G.-C., J.T.-A. and S.H.-O.; writing—review and editing, I.N.-S. and P.L.-R.; visualization, S.H.-O., I.N.-S. and P.L.-R.; supervision, J.T.-A.; project administration, S.H.-O. and I.N.-S.; funding acquisition, M.G.-C. and J.T.-A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Universidad de La Frontera, Project DI23-0032.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad de La Frontera (protocol code 140_23 and approved on 22 September 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethical reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Collin, P. Addressing the democratic disconnect. In Young Citizens and Political Participation in a Digital Society; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauja, A. Digital democracy: Big technology and the regulation of politics. Univ. N. S. W. Law J. 2021, 44, 959–982. [Google Scholar]

- We Are Social & Hootsuite. Digital Report 2022. Available online: https://wearesocial.com/es/blog/2022/01/digital-2022/ (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Subsecretaría de Comunicaciones [SUBTEL]. Series Estadísticas Tercer Trimestre 2024; Ministerio de Transportes y Telecomunicaciones: Santiago, Chile, 2024.

- Castells, M. El surgimiento de la sociedad de redes. In La era de la Información, Economía, Sociedad y Cultura. Siglo XXI; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, J.; Hacker, K. Internet and Democracy in the Network Society; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vromen, A.; Loader, B.; Xenos, M.; Bailo, F. Everyday making through Facebook engagement: Young citizens’ political interactions in Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States. Political Stud. 2016, 64, 513–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theocharis, Y.; Van Deth, J. Conceptual and empirical challenges in the study of citizen engagement. In Political Participation in a Changing World; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theocharis, Y.; Van Deth, J. The continuous expansion of citizen participation: A new taxonomy. Eur. Political Sci. Rev. 2018, 10, 139–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Mirpuri, S.; Rao, N.; Law, N. Conceptualization and measurement of digital citizenship across disciplines. Educ. Res. Rev. 2021, 33, 100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.; Glassman, M.; Cristol, D. What it means to be a citizen in the internet age: Development of a reliable and valid digital citizenship scale. Comput. Educ. 2017, 107, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Prados, J.; Lozano-Díaz, A. The challenge of active digital citizenship in European higher education: Analysis of cyberactivism among university students. EDMETIC Rev. Educ. Mediát. TIC 2021, 10, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.; Martin, F.; Sauers, N. Systematic review of 15 years of research on digital citizenship: 2004–2019. Learn. Media Technol. 2021, 46, 498–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Chan, K.; Lin, X. A systematic review of digital citizenship empirical studies for practitioners. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 3953–3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsper, E. The social relativity of digital exclusion: Applying relative deprivation theory to digital inequalities. Commun. Theory 2017, 27, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossberger, K.; Tolbert, C.; McNeal, R. Digital Citizenship: The Internet, Society, and Participation; MIt Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, S. Algorithms of Oppression; University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zuboff, S. Surveillance capitalism and the challenge of collective action. In New Labor Forum; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2019; Volume 28, No. 1; pp. 10–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Medina, L. Evade! Reflexiones en torno a la potencia de un escrito. Universum 2020, 35, 18–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Yañez, C. # Chiledespertó: Causas del estallido social en Chile. Rev. Mex. Sociol. 2020, 82, 949–957. [Google Scholar]

- Barbour, M. Misbehaving toddler or moody teenager: Examining the maturity of the field of K-12 online learning. Rev. Educ. Distancia (RED) 2020, 20, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Aguilera, G.; Imas, M.; Jiménez-Díaz, L. Jóvenes, multitud y estallido social en Chile. Rev. Latinoam. Cienc. Soc. Niñez Juv. 2021, 19, 230–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribble, M. International Society for Technology in Education. In Digital Citizenship in Schools: Nine Elements All Students Should Know; International Society for Technology in Education: Arlington, VA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-Díaz, A.; Fernández-Prados, J. Hacia una educación para la ciudadanía digital crítica y activa en la universidad. RELATEC: Rev. Latinoam. Tecnol. Educ. 2019, 18, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrén, E.; Fernández, M. Educación y Modernidad: Entre la Utopía y la Burocracia; Anthropos: Barcelona España, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, M.; Cristol, D. Digital citizenship with intersectionality lens: Towards participatory democracy driven digital citizenship education. Theory Into Pract. 2021, 60, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Baceta, M.; Gómez-Hernández, J. “Espacios de ciudadanía digital” en las bibliotecas públicas: Una propuesta para su integración en niversi del Plan nacional de competencias digitales. Anu. ThinkEPI 2021, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassman, M.; Kang, M. Teaching and learning through open source educative processes. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2016, 60, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo, M.; Ithurburu, V.; Sonsino, A.; Loiacono, F. Políticas digitales en educación en tiempos de Pandemia: Desigualdades y oportunidades para América Latina. Edutec. Rev. Electrónica Tecnol. Educ. 2020, 73, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanabria, A.; Cepeda, O. La educación para la competencia digital en los centros escolares: La ciudadanía digital. RELATEC Rev. Latinoam. Tecnol. Educ. 2016, 15, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorbecker, M.R. Interculturalidad, universidad y movimientos sociales latinoamericanos: Ideas desde la frontera norte. Soc. E Cult. 2014, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawamdeh, M.; Altınay, Z.; Altınay, F.; Arnavut, A.; Ozansoy, K.; Adamu, I. Comparative analysis of students and faculty level of awareness and knowledge of digital citizenship practices in a distance learning environment: Case study. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 6037–6068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.; Kim, S.; Jung, Y. Needs Analysis of Digital Citizenship Education for University Students in South Korea: Using Importance-Performance Analysis. Educ. Technol. Int. 2019, 20, 1–24. Available online: https://www.dbpia.co.kr/Journal/articleDetail?nodeId=NODE10693318 (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Lozano-Díaz, A.; Fernández-Prados, J. Digital citizenship and its measurement: Psychometric properties of one scale and challenges for higher education. Educ. Knowl. Soc. 2018, 19, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galván, M.; Salazar, A.; Tereucan, J. Nativos/as digitales en México: Evaluación de las Propiedades Psicométricas de la Escala de Ciudadanía Digital en estudiantes universitarios/as. Edutec Rev. Electrónica Tecnol. Educ. 2022, 82, 119–135. [Google Scholar]

- Kara, N. Understanding university students’ thoughts and practices about digital citizenship: A mixed methods study. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2018, 21, 172–185. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/26273878 (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Erdem, C.; Koçyigit, M. Exploring Undergraduates’ Digital Citizenship Levels: Adaptation of the Digital Citizenship Scale to Turkish. Malays. Online J. Educ. Technol. 2019, 7, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, N.; Ahn, S.; Jin, Y. Sample size and power estimates for a confirmatory factor analytic model in exercise and sport: A Monte Carlo approach. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2011, 82, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, I. Teoría Psicométrica; Mc Graw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Muñiz, J.; Elosua, P.; Hambleton, R. Directrices para la traducción y adaptación de los tests: Segunda edición. Psicothema 2013, 25, 151–157. Available online: https://www.cop.es/pdf/dtyatest.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Feenberg, A. Critical Theory of Technology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1991; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Lloret-Segura, S.; Ferreres-Traver, A.; Hernández-Baeza, A.; Tomás-Marco, I. El Análisis Factorial Exploratorio de los Ítems: Una guía práctica, revisada y actualizada. An. Psicol. 2014, 30, 1151–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goretzko, D.; Siemund, K.; Sterner, P. Evaluating model fit of measurement models in confirmatory factor analysis. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2024, 84, 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Seva, U. SOLOMON: A method for splitting a sample into equivalent subsamples in factor analysis. Behav. Res. Methods 2022, 54, 2665–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmerman, M.; Lorenzo-Seva, U. Dimensionality Assessment of Ordered Polytomous Items with Parallel Analysis. Psychol. Methods 2011, 16, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, Version 4.1; 2021 R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org. (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Rosseel, Y. lavaan: Latent Variable Analysis. [R Package]. 2018. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=lavaan (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Freiberg, D.; Stover, J.; Fernández-Liporace, M.; García-Cueto, E.; Muñiz, J. Correlaciones policóricas y tetracóricas en estudios factoriales con variables ordinales. Psicothema 2013, 25, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Büchi, M. Measurement invariance in comparative Internet use research. Stud. Commun. Sci. 2016, 16, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research; Guilford publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: Mayur Vihar, Delhi, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Elosua, P.; Zumbo, B. Coeficientes de Fiabilidad para escalas de respuesta categórica ordenada. Psicothema 2008, 20, 896–901. Available online: https://reunido.uniovi.es/index.php/PST/article/view/8747 (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Galperín, H. Sociedad digital: Brechas y retos para la inclusión digital en América Latina y el Caribe. In Policy Papers Unesco; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000262860.locale=es (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Peláez-Sánchez, C.; Glasserman-Morales, L. Gender Digital Divide and Women’s Digital Inclusion: A Systematic Mapping. Multidiscip. J. Gend. Stud. 2023, 12, 258–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, M. Ciudadanía e Identidad Digital en Mujeres Rurales: Procesos de Autoinclusión en las Tecnologías de la Información y la Comunicación. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Extremadura, Badajoz, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Steenkamp, J.; Baumgartner, H. Assessing Measurement Invariance in Cross-national Consumer Research. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 25, 78–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidov, E.; Meuleman, B.; Cieciuch, J.; Schmidt, P.; Billiet, J. Measurement equivalence in cross-national research. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2014, 40, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo-Medina, P.; Gómez-Lugo, M.; Marchal-Bertrand, L.; Saavedra-Roa, A.; Soler, F.; Morales, A. Desarrollo de guías para adaptar cuestionarios dentro de una misma lengua en otra cultura. Ter. Psicológica 2017, 35, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model A Multidiscip. J. 2007, 14, 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, P. Handbook of Psychological Testing, 2nd ed.; Routledge: NewYork, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, G.; Rensvold, R. Evaluating Goodness-of-Fit Indexes for Testing Measurement Invariance. Struct. Equ. Model A Multidiscip. J. 2002, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prensky, M. Digital natives, digital immigrants. Gifted 2005, 135, 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- Faure, A. ¿Se politizó el tiempo? Ensayo sobre las batallas cronopolíticas del octubre chileno. Universum 2020, 35, 46–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiliquinga-Amaya, J. Repertorio Digital: ¿Una Acción Colectiva Innovadora Para Los Movimientos Sociales? Kairós Rev. Cienc. Econ. Jurídicas Adm. 2020, 3, 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Helsper, E. The Digital Disconnect: The Social Causes and Consequences of Digital Inequalities; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Emejulu, A.; McGregor, C. Towards a radical digital citizenship in digital education. Crit. Stud. Educ. 2019, 60, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R.; Norris, P. Rising Tide: Gender Equality and Cultural Change Around the World; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sola-Morales, S.; Sabariego, J. Tecnopolítica, recientes movimientos sociales globales e Internet. Una Década Protestas Ciudad. 2020, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaste, A.; Cairns, D. Digital participation and digital divides in a former socialist country. In Young People’s Participation; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2021; pp. 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Allaste, A.; Cairns, D. Becoming a Digital Citizen in Estonia? New Migrants’ Interpretations of their Digital Participation. J. Appl. Youth Stud. 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).