1. Introduction

The rapid digitalization of workplaces, especially in Southern Europe and the Greek labor market, has created new challenges and opportunities for both employees and organizations. In Greece, the adoption of digital HRM tools is progressing, but organizations still face significant barriers, such as limited digital infrastructure, varying levels of digital competence among employees, and the strong influence of traditional organizational cultures. These contextual features make the Greek setting an important case for studying the interplay between digital transformation, human resource practices, and organizational culture.

In recent years, the integration of digital technologies into human resource management has brought substantial changes to organizational processes. According to Strohmeier (2020) and Marler & Parry (2016), digital HRM has evolved from an administrative support function to a strategic role that directly impacts workforce skills and organizational adaptability [

1,

2]. Tools such as e-recruitment, e-learning platforms, and performance management systems have become standard in HRM practice, and the development of employees’ digital skills has emerged as a significant challenge for many organizations. Despite this, the link between digital HRM practices and employees’ perceived digital competence remains insufficiently clarified, particularly in relation to the influence of organizational culture.

The current study addresses this issue by examining organizational culture as a potential moderator in this relationship. Although digital transformation has become a central strategic priority, the literature rarely combines digital HRM tools, employee digital abilities, and the dynamic effects of culture within one analytical framework. The originality of the study lies in the approach of treating culture not as an independent factor, but as a parameter that can either reinforce or diminish the effects of HR policies on digital competence.

This focus is motivated by gaps observed in recent research. Most published works focus either on the effects of HR practices on general organizational outcomes [

3], or on the role of culture in corporate strategy [

4]. However, there is a clear lack of studies that systematically examine how different organizational culture profiles may moderate the impact of digital HRM interventions on employees’ perceived digital skills. There is also limited empirical evidence on how specific cultural profiles shape the effectiveness of digital HRM interventions on employees’ perceived digital skills. Additionally, although approaches such as Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) and Multi-Group Analysis (MGA) have been applied in similar contexts, their simultaneous use in studies of digital transformation is still rare [

5].

This lack of integrated research makes it difficult for HR professionals to develop effective strategies truly adapted to the specific needs of their organizations, especially in countries like Greece, where the digital transformation is shaped by strong cultural factors. Therefore, addressing this research gap is not only important for academic knowledge but also crucial for the practical development of HRM policies and for guiding future research to better respond to real organizational challenges.

To address these questions, the present study is grounded in organizational behavior and digital transformation theories, as well as frameworks of organizational culture. Specifically, the research draws on established models such as Denison’s framework [

6], Cameron and Quinn’s competing values model [

7], and Hofstede’s cultural dimensions [

8] to analyze the role of culture in organizations. This approach allows the research to integrate established theoretical perspectives on how organizational environments and leadership influence the adoption of digital practices and the development of digital skills.

Research by Kemer & Tekeli (2022) highlights the connection between digital competence and professional insecurity, indicating the need to further explore the psychological dimensions of digital skills [

9]. At the same time, Vuorikari et al. (2025) point out the complexity of measuring digital competence and the need for more precise conceptual and psychometric instruments [

10]. Nevertheless, factors such as organizational culture that support the development and assessment of these skills remain underexplored.

Although some relevant studies have applied SEM, the combined use of SEM and MGA is uncommon, especially in settings where organizations are undergoing digital change [

5]. In addition, there is no clear empirical evidence as to which types of culture can enhance or limit the impact of digital HRM practices on employees’ digital competence. Although previous research has explored the relationship between digital HRM and organizational culture, few studies have examined how different cultural profiles moderate this relationship in digital transformation contexts. This gap hinders the practical application of these strategies [

1,

2]. Therefore, this study proposes an integrated model combining digital HRM, perceived digital competence, and organizational culture, analyzed using PLS-SEM and MGA.

The exploration of the relationship between digital HRM practices and employees’ digital competence has become an important area of study, particularly given the rapid technological developments. However, a key question remains unresolved: What is the role of organizational culture in this relationship? The main research question is: To what extent does organizational culture moderate the relationship between digital HRM practices and the perceived digital competence of employees?

This question is supported by previous studies that have shown the complex effects of both culture and HRM strategies [

3,

4]. At the same time, recent findings reinforce the importance of employees’ perceptions of their digital competence in their capacity to respond to the demands of digital transformation [

9,

10].

In light of these points, the present research adopts a multidimensional perspective to examine how specific types of culture—such as participative or hierarchical—may affect the effectiveness of digital HRM practices in improving digital competence. The use of SEM and Multi-Group Analysis can provide valuable evidence for the development of HRM policies that are both technologically advanced and sensitive to cultural factors [

5,

11,

12].

The potential contribution and originality of this research are highlighted in three main areas:

First, it offers empirical evidence from the under-explored Greek context, enriching the international literature on digital HRM and organizational culture. These contextual features make the Greek setting an important case because digital maturity in Greece lags behind EU averages—only 2.5% of the workforce are IT specialists vs. 4.6% EU average—and national initiatives like the Greek Digital Decade Roadmap and “Rebrain Greece” aim to accelerate skills development and digital adoption [

13,

14].

Second, by applying both SEM and Multi-Group Analysis, the study provides a methodological advancement in understanding how different cultural profiles shape the effectiveness of digital HRM practices.

Third, the findings can support practitioners and policymakers in designing targeted HRM strategies that are adapted to the specific cultural and digital maturity of their organizations, supporting more inclusive and effective digital transformation processes.

In summary, this study provides both theoretical and practical contributions.

This study makes a significant theoretical contribution by integrating organizational culture as a moderator in the relationship between digital HRM practices and employees’ perceived digital competence, offering new evidence from the Greek context and extending existing frameworks in digital transformation. On the practical side, the findings provide useful insights for HR professionals and policy makers, highlighting the need to tailor digital HR strategies to the cultural profile of each organization in order to maximize the development of digital skills.

In this way, the present study does not simply replicate previous research but adapts international theories and findings to the unique context of the Greek digital labor market, thereby offering both empirical and theoretical contributions.

2. Literature Review and Research Questions Development

The literature in this field is extensive and often complex, reflecting the major changes that digitalization brings to HR management and organizational life. For a systematic review, the analysis is organized into four main axes: the digital divide and inequalities in workplaces; the role of HRM practices in digital empowerment; the relationship between digital skills and employee performance; and the importance of equality and digital inclusion. Through these axes, the review aims to clarify the theoretical background and reveal the main research gaps, emphasizing the necessity of the present study.

2.1. Digital HRM Practices

Digital human resource management refers to the integration of modern digital technologies into HR processes, extending beyond basic digitization to include digitalization, transformation, and disruption [

2]. This evolution marks a shift from administrative tasks to data-driven and strategic HR roles [

1].

Digital solutions such as e-recruitment, e-learning, and performance management allow HR managers to participate actively in business strategy and workforce development [

15]. E-recruitment and onboarding platforms streamline hiring and help new employees adapt to organizational culture [

11,

16], while e-learning enables ongoing training and flexibility [

17].

Digital performance management systems and HR portals further support employee engagement, satisfaction, and internal communication [

15,

18].

Beyond automation, digital HRM is also essential for developing employee skills, adaptability, and innovation [

17,

19]. These practices enhance both technical and interpersonal abilities, supporting the overall employee experience [

15].

Despite these advances, a research gap remains: most studies focus on strategic or individual applications [

1], with limited empirical analysis of how digital HRM practices shape employees’ self-assessed digital competence. This gap motivates the present study.

Recent literature frames digital HRM not only as an extension of IT-based functions but as a strategic transformation for organizations. Strohmeier (2020) [

2] distinguishes digital HRM from e-HRM, emphasizing its broader focus on digital disruption and integration across HR functions. Similarly, Marler and Parry (2016) [

1] argue that digital HRM enables data-driven decision-making and strategic alignment, moving HR beyond administration. These perspectives are increasingly validated by empirical studies, which show that digital HRM practices such as e-recruitment, e-learning, and digital onboarding can boost employee skills and innovation [

17]. However, there is a continued research gap regarding the direct effect of these practices on self-perceived digital competence [

1,

2,

17].

The current literature leaves two key research questions (RQ) insufficiently addressed. First, to what extent do digital HRM practices influence employees’ perceptions of their digital competence (RQ1)? Second, which specific practices or combinations of practices are most strongly associated with these perceptions (RQ2)? Addressing these issues is particularly relevant, given the demonstrated link between perceived digital competence and critical outcomes such as performance, adaptability, and overall employee satisfaction in digitalized workplaces [

10].

Previous studies have indicated that digital HRM strategies contribute to employee development, yet have not provided clear evidence as to which digital tools have the greatest impact on perceived digital competence [

11,

15]. For this reason, further empirical investigation is warranted to clarify these relationships and provide actionable insights for organizations aiming to enhance digital skills within their workforce.

2.2. Digital Competence

Digital competence is defined as the ability to use digital technologies effectively and critically across diverse professional and personal settings. This goes beyond basic technical skills to include problem-solving, efficient communication, creativity, collaboration, and critical thinking—dimensions highlighted in frameworks such as the “21st Century Digital Skills” and DigComp [

20,

21].

In the workplace, perceived digital competence is the self-assessed ability to use digital tools, but this often does not match objective measures [

22,

23]. For example, younger employees or those in technical roles may overestimate their abilities, while advanced digital tasks often reveal true skill gaps [

10]. This underscores the need for validated assessment tools and targeted HRM strategies.

Personal factors—such as age, professional experience, and job role—significantly shape digital competence. Younger employees with greater exposure to technology report higher self-confidence, while relevant job experience and ongoing learning opportunities support advanced digital skills [

22,

23]. The combination of technical training and cognitive or social skills is essential for comprehensive digital competence [

21].

Despite growing research, most studies examine individual predictors of digital competence, with less attention to the combined influence of HRM practices and organizational context—thus highlighting an important research gap.

In addition to these frameworks, models such as the Technology Acceptance Model [

24], the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology [

25], and the Technology-Organization-Environment [

26] provide further theoretical depth for understanding digital competence. These frameworks emphasize the roles of perceived usefulness, ease of use, and organizational context in technology adoption—factors that are closely linked to the development of digital skills and confidence in the workplace. By integrating these perspectives, the present study acknowledges digital competence as both an individual capability and a product of broader organizational and technological factors.

The concept of digital competence is now widely recognized as multidimensional, including not only technical skills but also cognitive and social abilities. According to Van Laar et al. (2017) [

21], 21st-century digital skills encompass critical thinking, creativity, and communication. Kennedy and Sundberg (2020) [

20] further highlight the importance of adaptability and continuous learning in digital environments. The European DigComp framework offers a practical structure for measuring digital competence, which is increasingly relevant in workplace contexts [

10,

20,

21].

A growing body of research underscores the importance of these personal characteristics. Employees with greater exposure to digital environments and with job responsibilities that demand continuous learning tend to report higher self-perceived digital competence, while those with less digital experience or less demanding positions may express lower self-confidence in this area. This relationship informs the formulation of the third research question (RQ3): How do individual characteristics such as age, job position, and digital experience affect employees’ perceived digital competence? [

21,

22,

23,

27].

Evaluating the impact of digital HRM practices on employees’ digital abilities is especially important when considering employee perceptions. Employee experience is influenced not only by technology infrastructure but also by HRM strategies that prioritize digital training and foster a culture of continuous learning [

16,

17]. The digital transformation requires both technical skills and broader competencies like critical thinking, collaboration, and adaptability [

21].

Personal characteristics remain crucial: younger or more digitally experienced employees are more open to HRM initiatives for digital skills development [

23]. Organizational culture further interacts with these differences, shaping both the adoption of digital innovation and attitudes toward continuous learning [

3,

4].

The focus on sustainability and a digitally competent workforce increases the need for HRM practices that combine technical proficiency with a culture of ongoing learning [

2,

28]. Systematic measurement of perceived digital competence, using validated tools, is essential for designing effective HRM interventions [

10].

Despite this, few studies investigate how HRM practices and organizational culture jointly shape digital competence—highlighting a central gap that the present study aims to address.

In summary, digital ability should be understood not only as a technical qualification but as a dynamic, multidimensional construct shaped by personal characteristics, organizational context, and targeted HRM strategies. Future research would benefit from mixed-method approaches and a continued focus on the employee perspective in order to develop more effective and tailored digital policies.

2.3. Organizational Culture

Organizational culture encompasses the shared values, beliefs, and behaviors that shape organizations. Foundational models—such as Denison (1991), Cameron & Quinn’s OCAI, and Hofstede’s cultural dimensions—analyze involvement, adaptability, mission, and internal versus external orientations [

6,

8,

29]. These frameworks help categorize cultures as clan, hierarchy, market, or adhocracy and consider national as well as organizational influences.

A more systematic analysis of cultural dimensions reveals that each aspect of Hofstede’s model can influence digital HRM practices in distinct ways. For example, high-power distance cultures may resist participatory digital tools and prefer hierarchical, top-down e-HRM platforms, while low-power distance environments support more open communication and digital collaboration. Individualistic cultures might encourage self-directed digital learning and flexible HRM platforms, whereas collectivist settings may favor group-based e-learning and shared digital resources. Cultures with high uncertainty avoidance may adopt digital transformation more slowly, preferring tested, secure systems and extensive digital training. Conversely, cultures that are comfortable with uncertainty are more likely to experiment with innovative HRM technologies. By linking these cultural dimensions to digital HRM, we can better understand how organizational context shapes the adoption, effectiveness, and employee response to digital transformation [

2,

8].

In digital transformation, culture is increasingly recognized as a key factor. Innovative, flexible cultures support continuous learning and digital skill development, while hierarchical cultures may constrain digital innovation. Participative cultures foster knowledge sharing and digital engagement [

3,

4].

Recent studies show that culture shapes not only digital adoption, but also the environment for employees to build digital abilities [

23]. A supportive climate, leadership commitment, and openness to innovation (“digital culture readiness”) are linked to greater acceptance of digital systems and the acquisition of key skills such as creativity and collaboration [

30,

31].

Despite this, most research treats culture as a direct or independent influence, rarely exploring its moderating role on the relationship between digital HRM practices and employees’ digital competence [

17,

23,

30]. This gap justifies the focus of the present study.

The theoretical significance of organizational culture in digital transformation is well established in the literature. Models, such as those of Fondas & Denison (1991) [

6], Cameron & Quinn (2006) [

7], and Hofstede et al. (2010) [

8], provide a comprehensive basis for understanding how cultural values, leadership, and internal dynamics shape the adoption and effectiveness of digital HRM practices. Recent studies emphasize that a supportive, innovative, and learning-oriented culture not only facilitates the implementation of digital solutions but also moderates their actual impact on employee skills and attitudes. By explicitly adopting these theoretical perspectives, the present study addresses the gap noted by prior research regarding the moderating role of culture and ensures that the conceptual framework is directly embedded in recognized organizational theories. This approach also responds to the reviewer’s comment by linking the empirical investigation to the foundational concepts that dominate the field [

6,

7,

8].

Addressing this research gap, the present study focuses on the following question:

RQ4: How does organizational culture affect the relationship between digital HRM practices and employees’ digital competence?

A deeper understanding of this moderating effect is essential for designing HRM strategies that not only implement digital tools but also ensure their effectiveness across different organizational contexts. Such an approach recognizes organizational culture as a dynamic element that can either enhance or constrain the impact of digital initiatives, depending on its characteristics and values [

3,

4,

15,

28].

Investigating these interactions provides a more comprehensive theoretical foundation and supports the development of practical interventions tailored to the unique cultural profiles of organizations undergoing digital transformation.

2.4. Synthesis of Approaches and Identification of Gaps

Current research often explores the links between HRM, organizational performance, and digital change, but an integrated approach is still lacking. Kane et al. (2015) [

30] demonstrate that both digital strategy and innovation-oriented culture are essential for digital maturity and organizational performance, with technology integration alone being insufficient. Rather, a comprehensive strategy supported by a strong culture maximizes HRM’s impact on digital transformation [

30].

Marler & Parry (2016) highlight the mutual reinforcement between HR strategy and e-HRM technology adoption, showing that digital capabilities in HR yield benefits only when strategically managed [

1]. Empirical evidence, such as Tomczak et al. (2023), emphasizes digital self-efficacy as vital for employee satisfaction and adaptation, reinforcing the role of HR programs in skill development [

23].

Recent literature also notes the rise of AI, automation, and analytics in HRM, with leadership and change management critical for building a digital culture [

15]. In the context of sustainability, HRM acts as a mediator for advancing digital skills and promoting innovation [

28].

However, few studies offer an integrated model that examines the interplay among organizational culture, HRM practices, and employees’ digital competence [

32]. Most treat these variables separately, limiting understanding of their interdependencies and generalizability across different contexts [

15,

33]. Empirical studies that jointly evaluate these factors—across sectors, generations, or skill levels—remain rare, reducing the practical application of findings [

9,

23].

The literature acknowledges the importance of supportive culture but gives limited attention to how cultural context interacts with HRM practices during digital transformation [

17,

28]. Key distinctions between sectors, age groups, and skill levels are rarely analyzed within unified frameworks.

To address these gaps, Multi-Group Analysis (MGA) is proposed as a robust methodology to examine how digital HRM practices and culture jointly affect digital competence across different organizational profiles [

34,

35]. For example, participative cultures tend to foster digital integration, while hierarchical ones may slow progress [

32,

33,

36]. These variations highlight the need for HRM strategies tailored to specific organizational contexts.

In summary, the identification of research gaps in this study is not accidental but is directly grounded in the main organizational and digital transformation theories presented in the previous sections. By systematically synthesizing approaches such as the Competing Values Framework [

7], Denison’s model of organizational culture [

6], and recent literature on digital HRM [

1,

2], the present review highlights the specific areas where theory and practice are not yet aligned. This explicit theoretical embedding ensures that the formulation of the research questions and the conceptual model responds to both the latest scientific discussions and the reviewer’s comments for greater theoretical rigor and integration throughout the manuscript.

In light of these considerations, the following research question is proposed:

RQ5: Are there significant differences in the relationship between digital HRM practices and employees’ digital skills among different organizational culture profiles?

The application of Multi-Group Analysis is thus vital for uncovering contextual differences, supporting the design of effective digital HR strategies, and contributing to a holistic understanding of digital transformation in diverse organizational settings.

While widely adopted frameworks such as the Technology–Organization–Environment (TOE) framework [

37], the Diffusion of Innovation theory [

38], and Institutional Theory [

39] have provided strong bases for research on technology adoption and organizational change, the present study builds specifically on models of organizational culture and digital competence. This focus is chosen because the aim is not only to explore external or environmental factors but to examine in depth how different types of organizational culture moderate the relationship between digital HRM practices and employees’ digital competence. Nevertheless, many of the conceptual principles underlying TOE and Diffusion of Innovation—such as the interplay between technological, organizational, and human factors—are reflected in the integrated approach adopted here, where organizational culture serves as a key contextual moderator in the digital transformation of HRM practices.

This study is theoretically grounded in established frameworks of organizational culture, including Denison’s model, the Competing Values Framework by Cameron and Quinn, and Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, as well as contemporary theories of digital transformation in HRM. Considering the exploratory character of the analysis and the limited empirical evidence in the Greek context, the research adopts research questions instead of formal hypotheses. This approach aligns with methodological recommendations for PLS-SEM and MGA, where the main objective is to uncover complex patterns and interactions rather than to test narrowly defined causal links.

A key methodological contribution of the present study is the simultaneous application of PLS-SEM and Multi-Group Analysis (MGA) to investigate how different organizational culture profiles moderate the relationship between digital HRM practices and employees’ digital competence. While previous research has used SEM or MGA separately, very few studies have combined these techniques within a unified framework for digital transformation and HRM. This integrated approach enables us to uncover not only direct and moderating effects but also to identify significant differences in HRM effectiveness across specific cultural contexts. By explicitly focusing on cultural profiles—rather than technological tools alone—this study provides new insights into how the “fit” between HRM strategies and organizational culture influences the actual development of digital skills. Therefore, our research extends the literature by demonstrating that successful digital HRM interventions must be tailored to the unique cultural characteristics of each organization.

To summarize, the present review shows that the theoretical part of this study is grounded on three main axes: digital HRM practices, digital competence, and organizational culture. The review draws from established frameworks, including Denison’s model and the Competing Values Framework for analyzing organizational culture, Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, and the DigComp framework for defining digital competence. The literature reveals that, although digital HRM and digital competence have been widely studied, the interplay between these variables and the moderating role of organizational culture is not yet fully explored, especially in the Greek context. By combining these theoretical perspectives, the present study aims to fill important research gaps and provide a holistic understanding of how digital HRM practices, organizational culture, and digital skills are related in organizations.

2.5. Theoretical Framework and Conceptual Model

The conceptual model of this study is based on several well-established theories. First, Denison’s model and the Competing Values Framework by Cameron and Quinn provide the main foundation for analyzing organizational culture, helping to categorize culture types (e.g., supportive, innovative, hierarchical) as key variables in this study. Hofstede’s cultural dimensions further support the inclusion of cultural aspects that influence HRM practices. At the same time, the DigComp framework [

40] underpins the operationalization of digital competence as a multidimensional construct. By integrating these theories, the research model connects digital HRM practices, organizational culture, and employees’ perceived digital competence, with organizational culture examined as a moderator. This explicit theoretical foundation ensures consistency and scientific rigor in the variable selection and the analytical approach.

The conceptual model of this study is presented in

Figure 1 and clearly shows all the main constructs and the direction of the relations that are explored in the present research. The model was constructed based on the international literature and the most important theories about digital transformation, HRM, and organizational culture. The main target was to give a visual summary that helps the reader to understand the logic behind the selection of the research questions and to answer the reviewer’s request for a clearer connection between theory and the structure of the study.

More specifically, HRM Practices (that include General, Onboarding, Performance Management, and eLearning practices) are expected to influence directly the level of employees’ Digital Competence. This relationship is represented by a solid arrow, and it is connected with RQ1 and RQ2, which are focused on the impact of different HRM practices on digital skills. At the same time, the model includes the construct of Individual Characteristics, such as age, working position, and digital experience. The arrow from Individual Characteristics to Digital Competence shows that these types of personal variables can also affect the level of digital competence, as investigated in RQ3. In this way, the model combines both organizational and personal factors, as proposed by the most modern theoretical approaches in the field.

Finally, Organizational Culture is presented in the model as a moderator. The dashed arrow from Organizational Culture to the central relationship (HRM Practices to Digital Competence) means that the effect of HRM Practices can be stronger or weaker, depending on the culture that exists in each organization. This moderating role is the focus of RQ4 and RQ5. The inclusion of Organizational Culture in this position is justified by the relevant bibliography and also responds to the reviewer who noticed the lack of theoretical background for the research questions. With this structure, the model covers all the gaps of the literature that are mentioned before and connects theory with the empirical part of the study in a more systematic way.

3. Methodology

The methodological approach of the present study was based on the use of quantitative research, aiming at a thorough analysis of the relationships between digital human resource management practices and employees’ digital competence in modern working environments. The quantitative methodology was selected because it allows for the statistical processing of large amounts of data and the extraction of generalizable conclusions, in accordance with what is suggested by the relevant literature for the study of complex social and organizational phenomena [

41,

42].

The overall target population of the study consists of employees working in public and private organizations in Greece, aged over 18, and with at least 6 months of work experience. The sample includes employees from diverse sectors, industries, and job positions, thus reflecting a wide range of experiences and backgrounds relevant to digital HRM practices and digital competence in the Greek labor market.

The selection of a quantitative research methodology in this study is not arbitrary but directly reflects the nature of the research questions and the complexity of the relationships under investigation. Since the main aim is to statistically examine how specific digital HRM practices influence employees’ digital competence and to test the moderation effects of organizational culture across subgroups, a quantitative approach is both necessary and theoretically justified. Such methods allow for the measurement of latent variables, structural relationships, and the testing of differences between cultural profiles using advanced techniques like PLS-SEM and Multi-Group Analysis (MGA). This framework offers the empirical rigor needed to model complex, multidimensional constructs and to produce findings that can be generalized across different organizational contexts, in line with recent recommendations for research in digital HRM and organizational behavior [

43,

44].

The data collection took place from January to March 2025 using a digital questionnaire, which was created and distributed through the Google Forms platform. Initially, a contact list was prepared with employees from Greece from both the public and private sectors, making use of publicly available directories, company websites, and professional platforms. At the same time, the questionnaire was promoted via targeted groups in social networks such as LinkedIn. A combination of convenience and snowball sampling was applied, as the initial participants were asked to share the questionnaire with colleagues and other relevant contacts in order to achieve the greatest possible diversity of the sample [

42]. In total, approximately 620 invitations were sent and 257 fully completed responses were recorded, resulting in a response rate of about 41.5%, which is considered satisfactory for online surveys of this type.

The adequacy of the final sample size (

N = 257) was evaluated in line with international recommendations for PLS-SEM and MGA. According to Hair et al. (2022) [

43] and Sarstedt et al. (2017) [

44], this number exceeds both the “10-times rule” and the typical thresholds required to achieve adequate statistical power (usually

N ≥ 200–250 for models of moderate complexity). Although a formal a priori power analysis was not conducted, the achieved sample size is consistent with best practices and is considered sufficient for the robust estimation of both measurement and structural models, as well as for multi-group comparisons. For MGA, subgroup sizes were checked to ensure sufficient power for detecting meaningful differences between organizational culture profiles [

43,

44].

The necessary sample size was determined following international recommendations for Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). According to Hair et al. (2022) [

43], the minimum required sample size depends on the model complexity and the statistical power desired. Using the “10-times rule” as a basic guideline, the minimum sample size should be at least 10 times the largest number of indicators pointing to a single construct or the largest number of structural paths directed at a particular construct. In our model, the maximum number of indicators per construct is 10, resulting in a minimum requirement of 100 cases. Furthermore, recent simulation studies suggest that for models with medium complexity and path coefficients above 0.20, a sample size of 200–250 is recommended to achieve adequate statistical power [

43,

44]. Therefore, the final sample of 257 participants exceeds these requirements and is considered sufficient for robust PLS-SEM and MGA analysis.

After the data collection via Google Forms, all responses were downloaded in .xlsx format and underwent systematic data cleaning before analysis. Initially, all entries were screened for completeness, and any responses with missing data or logical inconsistencies (e.g., respondents under 18, duplicate submissions based on IP address and response timestamp) were excluded. Duplicates were identified by cross-checking submission times, user metadata (when available), and response patterns. The dataset was then checked for outliers and coding errors, and all categorical variables were properly labeled according to the predefined coding scheme. After final cleaning, the anonymized data were imported into SmartPLS (version 4.1.1.2, SmartPLS GmbH, Bönningstedt, Germany) for further analysis. No additional statistical checks for satisficing (e.g., straightlining, abnormally fast completion) were performed, which is acknowledged as a limitation and recommended for future research. All personally identifying information was removed or masked to ensure full compliance with GDPR and research ethics. To further ensure impartiality, all analyses were conducted exclusively on anonymized data, and no identifying information was available to the research team during the data analysis phase.

Although convenience and snowball sampling were employed to capture sectoral diversity, this approach inherently limits the external validity and generalizability of the findings. Future research should consider probabilistic or stratified sampling designs to improve representativeness and reduce selection bias.

Despite efforts to include participants from a wide range of sectors, job roles, and organizational sizes across Greece, the use of convenience and snowball sampling imposes inherent limitations on the strict representativeness of the sample. As a result, the findings should be interpreted with some caution regarding their generalizability to the entire population of Greek employees. Nevertheless, the diversity of the sample across key demographic and professional categories improves the relevance of the results for multiple organizational contexts.

Inclusion criteria required participants to be over 18 years old, employed in a Greek organization, and to have at least 6 months of work experience. Responses that were incomplete or identified as duplicates were excluded from analysis. As an example, a typical item used to assess digital competence was: “I feel confident using digital tools in my daily work” (measured on a five-point Likert scale).

To ensure the validity of the tools, a pilot testing phase was conducted with the participation of 15 employees from different specialties in order to identify possible ambiguities in the wording or technical problems. The comments were used to improve the clarity and the arrangement of the questions. The average completion time was between 22 and 27 min, according to the platform’s statistics, making it easier for participants to complete the process without being burdened.

The questionnaire was structured in two main parts. The first part included seven basic demographic questions: gender, age group, education level, job position, years of work experience, sector of employment, and organizational culture profile. The three organizational culture profiles (supportive, innovative, and hierarchical) were pre-defined in advance based on the theoretical framework of the Organizational Culture Assessment Instrument (OCAI) developed by Cameron and Quinn (2006) [

7]. Each respondent completed a set of items reflecting these culture types, and average scores were calculated for each dimension. Participants were assigned to the profile corresponding to their highest average score, following the standard coding procedure recommended in the OCAI manual. The choice of these categories is supported by their strong theoretical relevance in the literature and their widespread adoption in previous studies on organizational culture and HRM. This approach ensures comparability and interpretability for multi-group SEM analysis. The use of this typology allows for systematic, theory-driven comparisons across the most commonly examined culture types in digital HRM and transformation research [

7].

In the second part, five thematic sections were developed with a total of 50 closed-ended questions, answered on a five-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all, 5 = Very much). These sections covered distinct fields of digital HRM (see

Table 1):

- ➢

General digital HR practices (HRM_General)

- ➢

Digital Onboarding (HRM_Onboarding)

- ➢

Performance management through digital tools (HRM_PerfMgmt)

- ➢

E-learning (HRM_eLearning)

- ➢

Digital Competence

The choice of online and anonymous questionnaire completion offered advantages regarding the breadth of reach, low cost, and the possibility of collecting data from different professional environments [

41]. In addition, participants had the possibility to respond with flexibility regarding the time, which often improves the reliability of the answers. On the other hand, some limitations are recognized, such as limited control of the sample composition and self-selection bias, as well as the exclusion of people with limited digital skills [

42].

Potential for social desirability bias and common method variance is acknowledged, as responses were self-reported and participation was voluntary. While the anonymity of responses aimed to mitigate such risks, no specific statistical control for social desirability was implemented in this study.

The sample size (N = 257) is consistent with recommendations for Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) in social research. For the Multi-Group Analysis (MGA), group sizes were checked to ensure sufficient power for meaningful comparisons between the main culture profiles.

The use of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was justified by both the nature of the research model and the characteristics of the data. PLS-SEM is particularly suitable for studies that involve multiple latent constructs, complex relationships, and moderate sample sizes, as in the present research. It enables the simultaneous estimation of measurement and structural models, allowing for a rigorous test of hypotheses about the direct and moderating effects among digital HRM practices, organizational culture, and digital competence [

43,

44]. The technique also handles non-normal data distributions effectively, which was relevant given the observed characteristics of the collected data.

The Multi-Group Analysis (MGA) was selected to compare the effects of HRM practices across different organizational culture profiles. MGA is well established for testing whether relationships in a structural model differ significantly between predefined groups [

34,

44]. This approach is theoretically aligned with the research aim of identifying whether the impact of digital HRM varies as a function of organizational culture, providing deeper insight into the moderating mechanisms at play.

The choice of these techniques is consistent with recent methodological recommendations for digital HRM and organizational behavior research and provides robust tools for addressing the multidimensional and context-sensitive nature of the research questions.

The whole process was carried out with full respect for ethical and legal standards. The provisions of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) were strictly followed, and the research was harmonized with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki [

45]. All participants were fully informed about the purpose and the terms of participation, anonymity was guaranteed and the right to withdraw voluntarily was ensured, and no personal information was used beyond the purpose of the study.

For the analysis of the data and the estimation of the relationships within the theoretical model, the software SmartPLS (version 4.1.1.2, SmartPLS GmbH, Bönningstedt, Germany) was used. This platform was chosen due to its flexibility in analyzing complex structural models with multiple construct variables, particularly in cases with moderate sample sizes and non-normal data distributions. SmartPLS offers advanced tools for PLS-SEM and MGA, allowing for simultaneous estimation of measurement and structural models, reliability and validity checks, and robust group comparisons—features that are especially suitable for the aims and data structure of the present study [

43].

For the assessment of the reliability and validity of the variables included in the structural model, three main statistical indicators proposed in the international literature were used (

Table 2). First, Cronbach’s alpha index was calculated, which shows the degree of internal consistency among the questions forming each construct variable. The values that were found for all the main variables of the analysis were at very high levels, with the lowest at 0.941 and the highest at 0.964. This fact confirms that the individual questions of each scale are strongly connected and consistently represent the theoretical background of each variable. These findings are in line with the minimum threshold suggested in the literature, where values above 0.70 are considered acceptable for research purposes [

46].

Next, composite reliability was examined, both with the rho_a and rho_c indicators. Composite reliability is calculated by taking into account the weighted loadings of the indicators, so it is considered more representative of the real consistency, especially when the analysis is based on factor models, as in the present study. For all measured variables, the values of composite reliability exceeded the 0.70 threshold by far, with the lowest reaching 0.945 and the highest 0.969, which shows even more strongly the stability and reliability of the measurements [

43].

Regarding convergent validity, which is checked with the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) indicator, the values observed for the construct variables in this study ranged from 0.653 to 0.756. Given that the accepted minimum threshold in the literature is set at 0.50 [

47], these values show that each variable sufficiently explains the variance of its related indicators, thus strengthening the validity of the measurement.

Overall, the analysis of the above indicators supports the conclusion that the measurements used in the research present a high degree of reliability and convergent validity. These results provide the possibility to proceed with further analysis of the structural model with statistical safety, as it is ensured that the research conclusions will be based on measurements with stable internal consistency and sufficient validity.

Additionally, for the further assessment of discriminant validity, the HTMT (Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio of Correlations) index was calculated (

Table 3), which is now considered in the literature as the most reliable method for distinguishing between construct variables in structural models. This index compares the average correlation between different constructs with the average correlation between the indicators of the same construct, and according to the recommendations of Henseler et al., values below 0.85 or 0.90 indicate acceptable discriminant validity [

34]. In the present analysis, the HTMT values for all pairs of variables ranged from 0.122 to 0.343, much lower than the mentioned thresholds, a fact that strengthens the finding that the variables of the model are sufficiently distinguished from each other. This result highlights that each concept measured in the questionnaire is statistically distinct and independent, which adds further validity to the conclusions of the study.

The overall picture that results from the analysis of reliability and validity of the model is particularly positive, as both the results of the internal consistency and convergent validity indicators, as well as the checks of discriminant validity, support the suitability of the measurements for further statistical processing and the extraction of research conclusions.

In addition, the Fornell-Larcker criterion was applied for the assessment of discriminant validity, as is recommended in structural model analyses (

Table 4). According to this method, for each construct variable, the square root of the AVE index is calculated and compared with the correlations that exist between this variable and the other variables in the model. The theoretical criterion states that the square root of the AVE for each variable should be higher than any bivariate correlation related to it [

47]. In the present analysis, the values of the main diagonal of the corresponding matrix, which correspond to the square roots of AVE, were satisfactorily higher than the values of the off-diagonal correlations for each variable. Specifically, for all variables of the model—Digital Competence, HRM_General, HRM_Onboarding, HRM_PerfMgmt, and HRM_eLearning—the square root of AVE ranged from 0.808 to 0.870, while all their correlations with other variables were significantly lower. This observation confirms in a statistically documented way that the construct variables are distinct from each other, further strengthening the validity of the model’s results.

Moreover, to assess the risk of common method variance (CMV) due to the exclusive use of self-report measures, Harman’s single-factor test was performed via exploratory factor analysis (EFA), including all measurement items. The results indicated that the first factor accounted for 26.4% of the total variance, well below the commonly used 50% threshold, suggesting that CMV is not a significant concern in this study [

48].

The overall picture of the results, based both on the Fornell-Larcker criterion and the HTMT index, indisputably supports the discriminant validity of the variables included in the analysis. Given the clear documentation of reliability and validity of the measurements, further investigation of the research questions can be carried out with greater scientific safety and reliability.

Prior to the assessment of multicollinearity (VIF), a dimensionality check for all latent constructs was conducted. This was performed through Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) within the PLS-SEM framework, evaluating factor loadings, Average Variance Extracted (AVE), and composite reliability. All indicators for each construct showed strong loadings (above 0.70), and AVE values exceeded the 0.50 threshold, confirming the unidimensionality and convergent validity of each latent variable [

43]. Only after confirming satisfactory unidimensionality and construct validity, the VIF was calculated to assess potential multicollinearity among the latent variables.

Within the framework of the analysis, multicollinearity indicators between the main constructs were also examined, using the Inner Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), in order to determine if there are phenomena of high correlation that could affect the results of the model (

Table 5). The values that emerged were extremely low for all variables, ranging from 1.08 to 1.15, much lower than the maximum accepted threshold in the literature, which is set at 5 (or even lower in stricter approaches). This indicates that there are no signs of multicollinearity among the construct variables of the model, further strengthening the statistical correctness and the reliability of the estimations derived from the analysis [

49].

To assess the predictive relevance of the model, Stone-Geisser’s Q

2 statistic was calculated for each indicator of Digital Competence using the blindfolding/PLS Predict procedure in SmartPLS. All Q

2 values were positive (ranging from 0.053 to 0.167), which confirms that the model demonstrates adequate predictive relevance for Digital Competence [

43,

44].

In conclusion, the methodological approach adopted in this study is characterized by a systematic and rigorous design, following international standards for quantitative research. The careful selection of the sample, the use of validated measurement tools, and the detailed reliability and validity checks ensure the scientific robustness of the data. This methodological framework allows for the extraction of valid and generalizable conclusions, supporting the main research aims and setting a solid basis for the presentation and interpretation of the results in the

Section 4.

5. Discussion

The section that follows aims to interpret the main findings of the present research, taking into account the relevant theory and the international bibliography. The central goal of the discussion is to assess to what extent the research questions are confirmed, and also to highlight the specific characteristics of the Greek work environment in relation to digital HRM practices. Special focus is given to comparing the results with previous empirical and theoretical approaches so that the contribution of this research to the global discussion about digital competence in the workplace can be clearly presented.

The interpretation of the present findings is explicitly anchored in major organizational theories and frameworks outlined in the literature review. By comparing our empirical results with foundational models such as Denison’s (1991) organizational culture [

6], the Competing Values Framework [

7], and current digital HRM theories [

1,

2], this discussion provides a theoretically grounded understanding of how digital transformation processes interact with both organizational structures and individual characteristics. This approach directly addresses the reviewer’s comment by ensuring that each empirical insight is interpreted not only in relation to the data but also with respect to the dominant theories that inform contemporary research in this field. In this way, the contribution of the study is embedded both in empirical findings and in the ongoing theoretical conversation on digital competence and HRM.

First, the answer to the first research question was obtained through the application of the PLS-SEM methodology in SmartPLS 4. The data from the questionnaire, which used multidimensional and theoretically supported scales for the digital HRM practices and digital competence, were transformed into latent variables and grouped according to the recent literature [

43]. The validation of the model’s structure was confirmed with indicators for validity and reliability, while the SRMR index was impressively low (0.041), a fact which indicates a very good fit of the model to the data.

In the analysis of the path coefficients (see

Table 7), all the paths from digital HRM practices to digital competence appeared positive and statistically significant. More specifically, the most important effect was observed for the dimension of digital training (HRM_eLearning → Digital Competence, β = 0.243,

p < 0.001), followed by digital onboarding, general digital HRM practices, and performance management. It is important to note, however, that all effect sizes for these relationships were small (f

2 < 0.07), a finding that reflects the multi-factorial and complex nature of digital competence development in organizational settings.

While these results are largely consistent with previous research [

1,

58], it is notable that the effect sizes remain small, even in a Greek context where digital transformation is still in progress. This may reflect contextual barriers unique to Southern European workplaces, such as persistent traditional cultures or slower rates of technology adoption [

13,

14].

These results are in full agreement with the bibliography that highlights the importance of digital HRM practices for skills development [

1,

2,

30,

58]. For example, Marler & Parry (2016) argue that the systematic use of digital HRM tools increases the maturity and adaptability of employees, while Ifinedo (2017) demonstrates the central role of e-learning in the continuous upgrading of knowledge and skills [

1,

58].

The small effect sizes observed suggest that while digital HRM practices do make a statistically significant contribution to employees’ digital competence, there are likely additional organizational and personal factors that play a more substantial role. These results are consistent with prior studies indicating that digital skills are influenced by a wide array of variables—including leadership style, organizational support, employee motivation, and individual learning orientation [

1,

10,

58]. This reinforces the notion that technological interventions alone are not sufficient and highlights the importance of a holistic, multidimensional approach to digital transformation in the workplace.

Subsequently, the answer to the second question became evident through the analysis of the effect sizes (f-square) and the path coefficients between the latent variables, as calculated in PLS-SEM. The results show that digital training (eLearning) presents the highest effect (f

2 = 0.069), followed by digital onboarding (f

2 = 0.042), general digital HRM practices (f

2 = 0.024), and performance management (f

2 = 0.021). All values fall in the category of small but positive effects, as described in the international standards. The HRM_eLearning → Digital Competence path was the most important, both statistically and in interpretation [

43,

49].

One particularly interesting finding is the relatively stronger effect of e-learning compared to other digital HRM practices. While Strohmeier (2020) and Ifinedo (2017) emphasize the role of digital training, our study suggests that in contexts with moderate digital maturity, targeted e-learning programs may serve as the main driver for digital competence, perhaps compensating for weaker onboarding or performance management processes [

2,

58].

The notably higher effect size observed for e-learning likely reflects the unique characteristics of digital training platforms, which engage employees in interactive, continuous, and self-paced learning. Unlike onboarding or performance management, which often emphasize procedural knowledge or evaluation, e-learning requires active participation and the direct application of digital tools to real tasks. This ongoing exposure and hands-on practice are particularly effective in building both confidence and competence with digital technologies, a finding also echoed in the recent literature [

2,

58]. Importantly, the stronger impact of e-learning was consistent across the different organizational culture profiles analyzed in our study, suggesting that digital training may function as a universal lever for upskilling, even in environments with varying cultural characteristics.

From a practical standpoint, these results highlight the value of investing in high-quality, adaptive e-learning platforms as a central part of HRM strategy. Organizations seeking to enhance workforce digital competence—regardless of their prevailing culture—should prioritize digital training programs that offer personalized, interactive learning opportunities. Moreover, aligning e-learning initiatives with broader HRM and cultural strategies may further amplify their positive effects, supporting a more resilient and digitally capable workforce.

The bibliography confirms these findings: Strohmeier (2020) and Ifinedo (2017) underline that participation in digital training leads to faster skill development and facilitates employees’ adaptation to new digital technologies [

2,

58]. Also, Vuorikary et al. (2025) and Bondarouk et al. (2017) conclude that the use of integrated onboarding systems, which include personalized support, facilitates quick integration and the cultivation of digital competences [

10,

63].

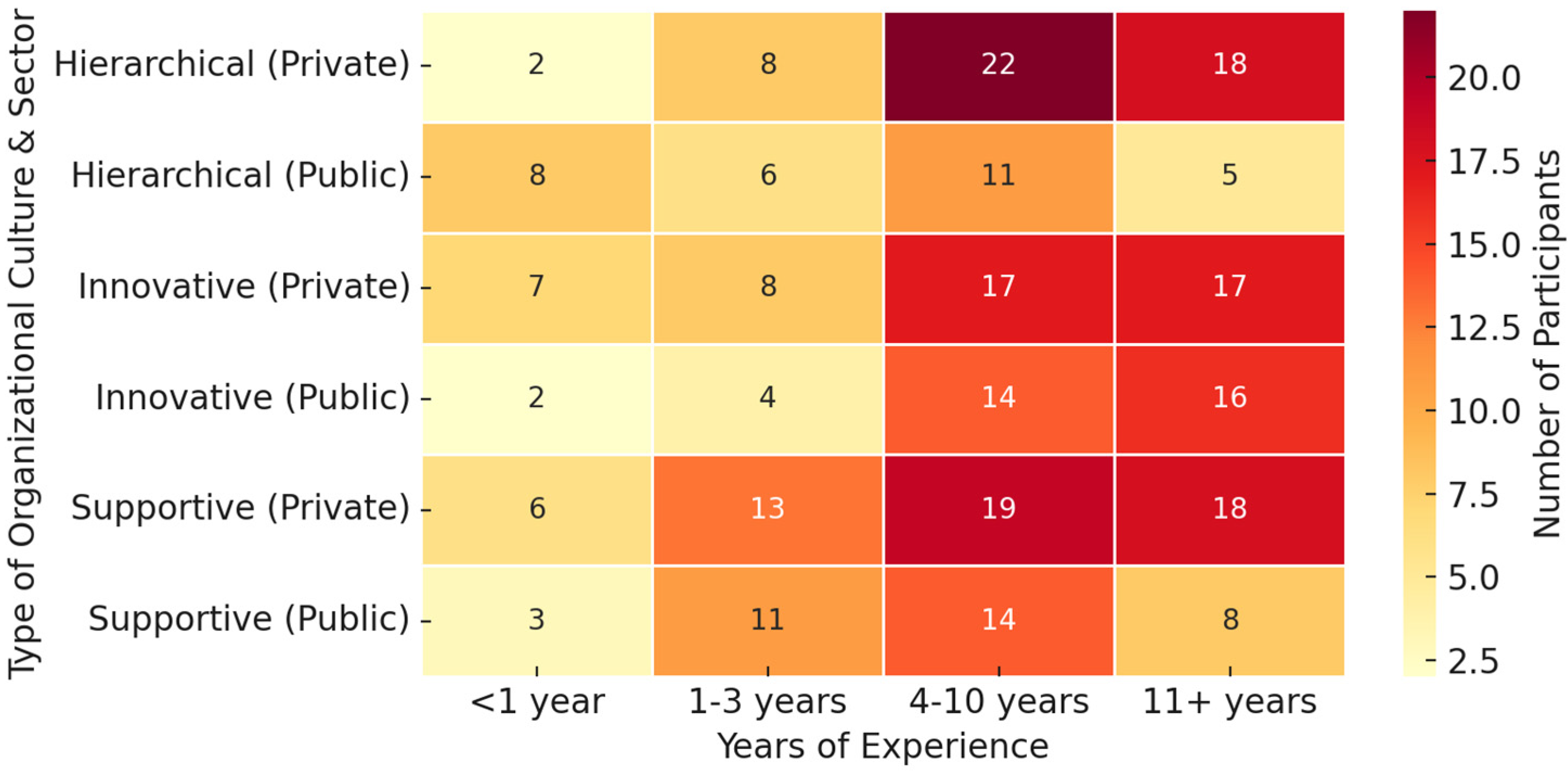

Continuing the analysis, RQ3 was based on combined visualization of the demographic data with heatmap diagrams, as well as exploration of patterns in the correlations between characteristics such as education level, job position, years of experience, and culture type. The distribution tables and the visualizations with Python (matplotlib, seaborn) showed that younger employees, with higher education, higher positions, and extended digital experience, tend to report higher digital competence.

The international bibliography is in line with the above findings: Van Laar et al. (2017) [

21] and Ciobanu et al. (2023) [

64] point out that digital competence is related both to lifelong learning and to access to environments that support continuous technological adaptation. Kraimer et al. (2011) [

55] add that organizations with innovation or supportive culture are more likely to retain highly educated and experienced employees, improving the chances for transition to digital practices [

21,

55,

64].

These findings further highlight that demographic and personal characteristics—such as age, education, experience, and job position—remain essential determinants of digital competence, often mediating or moderating the impact of HRM interventions. Future research should aim to model these factors more explicitly and, where possible, include them as control or mediating variables in structural models.

The fourth research question was not examined empirically, as the SEM model did not include mediating variables that would allow for mediation analysis. Although the international bibliography considers culture a main enhancer or mediator in the functioning of HRM practices, in the present research, the analysis was limited to direct effects because of restrictions in the structure of the data and variables. The exploration of mediation is proposed as an important field for future research. It is recommended that future studies should employ research designs that allow the exploration of mediation effects, potentially through the inclusion of additional variables such as leadership support, employee motivation, or digital infrastructure quality. Such mediation analyses would provide a more nuanced understanding of the mechanisms underlying the HRM–digital competence relationship [

29,

60,

65].

Finally, for the fifth research question, Multi-Group Analysis (MGA) with Permutation Test in SmartPLS 4 was applied. The results (

Table 9,

Table 10 and

Table 11) showed clearly that the effectiveness of digital HRM practices is significantly different depending on the profile of organizational culture. Specifically, the positive effect of onboarding on digital skills was much stronger in supportive cultures compared to innovative ones, while performance management had an opposite effect between supportive and hierarchical environments [

43,

44].

It is important to note that perceived digital competence, as measured in this study, may not always reflect objectively assessed digital skills. Prior research [

22,

23] shows that individuals often overestimate or underestimate their digital abilities due to psychological factors such as self-efficacy, confidence, or cognitive bias. This potential discrepancy is especially relevant in self-report surveys, where overconfidence can inflate perceived competence levels, while anxiety or lack of exposure may lead to underreporting. The psychological aspects of digital literacy—such as digital self-efficacy and self-regulation—are, therefore, important contextual factors and should be further explored in future research.

The Multi-Group Analysis revealed that the effect of digital onboarding practices on employees’ perceived digital competence varied substantially by organizational culture profile. For example, in organizations characterized as “supportive,” the onboarding–competence path was notably stronger, indicating that newcomers in such cultures benefit more from digital onboarding processes and feel more confident in their digital skills. In contrast, in “innovative” cultures, while the onboarding process is still significant, the relationship with digital competence was weaker and not always statistically robust. This may be due to the fact that innovative cultures emphasize autonomy and experimentation, which can empower some employees but may also result in less structured support during onboarding. Therefore, digital onboarding alone may not be sufficient to ensure high levels of digital competence in innovative environments, and complementary mentoring or peer-learning programs may be necessary.

Moreover, while the overall positive association between innovative culture and digital skills aligns with global evidence, the finding that supportive (rather than purely innovative) cultures maximize the effectiveness of digital onboarding is noteworthy. This may suggest that in transitional economies, supportive organizational climates are more important than abstract innovation for successful digital transformation.

One unexpected finding in our analysis is the weaker or even negative effect of certain HRM practices—such as onboarding or performance management—within innovative culture profiles. This diverges from much of the existing literature, which typically associates innovative cultures with higher adaptability, learning, and openness to new technologies [

2,

7]. A possible explanation for this divergence is that highly innovative environments often emphasize autonomy, experimentation, and less structured support. While this may benefit certain digitally confident employees, it could also result in newcomers or less experienced staff receiving insufficient guidance during critical transition periods, thereby diminishing the impact of onboarding or structured feedback. This suggests that the advantages of innovation-oriented cultures for digital competence may not be uniform across all HRM practices or employee groups and could even create disparities in digital upskilling if not balanced with adequate support mechanisms.

These findings partly challenge the common theoretical assumption that innovative cultures are always optimal for digital competence development. Instead, our results highlight the importance of context-specific, balanced approaches: even in highly innovative organizations, targeted onboarding, mentoring, or structured feedback may be necessary to ensure that all employees benefit equally from digital transformation initiatives. This nuanced understanding calls for a re-examination of how culture moderates HRM effects and supports the call for more differentiated models of digital competence development in future research.

These results are in full agreement with theoretical and empirical studies supporting that organisational culture influences both the acceptance and practical application of HRM practices [

29,

59,

60,

66].

5.1. Practical Implications

The present study reveals some important conclusions for the practical application of digital HR practices inside organizations, especially when the role of organizational culture is considered. Firstly, it becomes clear that the successful integration of digital tools and HRM processes cannot depend only on technology. The organizational culture is the foundation for the acceptance and effective use of these practices. Every effort to improve the digital competence of employees must be combined with the cultivation of an environment that encourages learning, innovation, and collaboration [

15,

17].

Furthermore, the findings show that HR strategies should be adapted to the culture profile of each organization. In environments where participation and openness are dominant, the use of digital tools can be supported by involving employees in the decision-making and in the continuous exchange of knowledge. On the other hand, in organizations with more hierarchical or conservative cultures, a more systematic guidance, intensive training programmes, and strong support from the management are needed in order to overcome resistance [

16,

28].

The Multi-Group Analysis provides clear guidance for HR managers on tailoring digital HRM interventions to organizational culture. In supportive cultures, where onboarding practices have a strong positive effect on digital competence, managers should prioritize structured digital onboarding programs with personalized mentoring and collaborative learning opportunities, ensuring newcomers are guided and supported during integration. In innovative cultures, however, the same onboarding programs are less effective, likely because employees are expected to learn autonomously. Here, managers should complement onboarding with peer-driven projects, digital skill challenges, and opportunities for experimentation, fostering a culture of continuous self-learning rather than relying solely on formal training [

54,

67,

68].

For hierarchical cultures, where the effect of digital performance management diverges from supportive cultures, managers should emphasize clear, structured digital procedures, regular feedback, and digital compliance training, as employees in such environments may benefit from explicit guidelines and consistent evaluation. Conversely, in more participative or clan cultures, digital HRM interventions should leverage collaborative tools, team-based digital learning, and participatory decision-making processes to maximize engagement and digital upskilling [

67,

68].

These findings highlight that a “one-size-fits-all” digital HRM strategy is unlikely to be effective. Instead, organizations should assess their unique cultural profiles and adapt both the content and delivery of digital HRM initiatives—including onboarding, e-learning, and performance management—to match the specific motivations, learning preferences, and support needs of their workforce. In all contexts, the integration of digital skill development with cultural and structural characteristics of the organization is essential for meaningful improvements in employee competence.

For example, in supportive or clan cultures, digital HRM practices can leverage collaborative tools, interactive e-learning modules, and participative decision-making platforms to foster engagement and knowledge sharing. Introducing digital mentorship programs, cross-functional team projects, or internal knowledge networks can be highly effective, as employees in these environments value interpersonal support and open communication [

54].

In contrast, in hierarchical cultures, digital HRM strategies should focus on clear, structured procedures and top–down communication. Effective practices might include standardized digital onboarding programs with step-by-step instructions, mandatory compliance modules, and regular digital skills assessments. Managers should provide frequent feedback through digital performance dashboards and ensure that employees receive explicit, management-driven guidance on digital practices [

53,

54,

69].

For organizations aiming to increase cultural adaptability, it is important to periodically review and adjust digital HRM interventions based on employee feedback and changing organizational needs. Hybrid approaches—such as combining structured digital learning with optional peer-learning groups—can help bridge gaps between different cultural profiles, promoting both stability and innovation. By continuously aligning HRM practices with the evolving cultural context, organizations can maximize digital competence and employee engagement [

53,

54,

69].

Investment in education and development of digital skills should not be limited only to technical training. It is necessary to also include competences such as adaptability, digital mindset, and critical thinking, which are main factors for dealing with the continuous changes in the digital workplace. Through a holistic approach that combines technical knowledge and cultural support, organizations can strengthen the confidence and productivity of their employees [

21,

53].

Finally, the study highlights the need for flexibility and continuous feedback in digital initiatives. Organizations must adapt their practices constantly so that they respond to the changing technological and cultural conditions. In this way, they ensure the sustainability and maximum performance of their investments in digital human resources, while, at the same time, they create an environment that strengthens innovation and the participation of all employees [

30,

36].

5.2. Theoretical Implications

This study makes an essential contribution to the evolution of theoretical understanding in digital transformation and HRM by directly drawing on and extending established frameworks such as Denison’s organizational culture model [

6], the Competing Values Framework [

7], Hofstede’s cultural dimensions [

8], and the European DigComp framework for digital competence [

40]. These theoretical models formed the conceptual foundation for the research design, analysis, and interpretation of results throughout the manuscript.

The findings of this study empirically confirm and nuance these frameworks in several ways. First, consistent with Denison’s model, organizations characterized by higher flexibility and adaptability showed a stronger positive effect of digital HRM practices on employee digital competence. Second, the results expand the Competing Values Framework by showing that participative (clan/adhocracy) cultures are especially conducive to digital skills development, whereas hierarchical cultures tend to moderate or inhibit the effectiveness of digital HRM interventions. Third, with respect to the DigComp model, our results suggest that workplace digital competence is not only a matter of individual ability but is substantially shaped by organizational context and culture—an insight that supports the model’s recent extensions into organizational settings [

6,

40,

69].

This study makes an essential contribution to the evolution of the theoretical understanding regarding how organizational culture shapes the relationship between digital human resource management practices and the digital competence of employees. While the literature has separately recognized the importance both of digital HR practices and organizational culture, only a few studies have gone deeper into the role of culture as a factor that mediates and modifies the effectiveness of such practices for the development of skills.

Through the application of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) and Multi-Group Analysis (MGA), the present research reveals how specific cultural characteristics, such as participation or hierarchical structure, can strengthen or limit the impact of digital HR practices on the formation of perceived digital competence. This approach opens new ways to consider organizational culture not only as a fixed condition, but as a dynamic factor that adapts the relationship between technology and the human factor [

34].

Moreover, this study strengthens the theoretical understanding of digital competence as a multidimensional phenomenon, which depends not only on individual skills but also on the supportive environment shaped by the culture of the organization. In this way, the proposed framework contributes to the unification of different theoretical fields: digital HRM, organizational behavior, and skills development [

23].

At the same time, the research highlights the importance of adapting digital HR strategies to the specific cultural characteristics of each organization, a fact that adds depth to the theories about digital transformation. This approach underlines that technology alone is not enough for achieving digital maturity; a flexible and culturally sensitive environment that encourages learning and innovation is needed [

10].

One important theoretical implication that emerges from this study is the need to view digital competence as a truly multidimensional construct that results from the dynamic interplay between individual-level skills and the broader organizational culture. While individual technical abilities, adaptability, and motivation are essential components, our findings suggest that their development and expression are strongly facilitated—or at times constrained—by the prevailing cultural environment within the organization. For example, employees with high digital aptitude may flourish in participative cultures that support collaboration and continuous learning but may struggle to fully develop or apply their skills in more hierarchical or rigid settings. Conversely, in supportive cultures, even employees with lower initial digital competence may advance more quickly due to positive peer effects and institutional encouragement [

10,

21,

63].