Abstract

As digital marketing becomes more targeted and interactive, it is more critical to understand how young audiences perceive and react to compelling content. This research examines the extent to which consumer responses are affected by neuromarketing knowledge, interest, and screen-based advert exposure for middle school kids. Based on responses from 244 Greek adolescents aged 12–15 years, Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was employed to investigate direct and mediated influences on purchase intentions with advertisement skepticism and persuasion knowledge as mediating factors. Results indicate that exposure and recognition have a significant influence on intentions both by means of cognitive as well as attitudinal processes, while interest only increases skepticism but not interaction. Multi-group analysis yielded significant differences according to age and experience, referring to the development path of advertising literacy. The results provide strong cues to educators, policymakers, and marketers who want to develop media-critical competencies among adolescents in an ever-shaping digital age.

1. Introduction

Screen-based advertising to children has exploded over the past decade, with child audiences routinely exposed to branded content across platforms including YouTube, TikTok, social media, educational websites, and mobile apps [1,2]. For instance, in 2024, according to a Pew Research Center survey, 90% of American teenagers use YouTube, and roughly 60% use TikTok on a frequent basis [3,4]. These sites generally insert branded communications or advertisements—e.g., advergames—into games and videos, employing persuader design elements like algorithmic personalization, gamification, narrative storytelling, and emotional appeals to capture attention and influence behavior. Thus, online advertising has become a ubiquitous aspect of children’s daily media lives. Studies show that children are exposed to a high volume of advertisements in a year and that many online platforms have a number of advertisements in a single video [5,6]. This ubiquitous integration ensures that advertising is no longer relegated to the sole preserve of conventional commercial breaks but is integrated into the digital spaces that children use on a daily basis. In such a case, recognizable online environments and characters tend to erode the boundaries between entertainment and advertising. Marketers today speak of the “digital marketing ecosystem” as a networked, data-driven space within which children are simultaneously targets and influencers, wielding purchase power and informing peer and parent purchases. This has developed at a pace that has outstripped conventional regulatory approaches, fueling anxiety regarding children’s exposure to influence technologies and algorithmic targeting [5,6]. Developmental psychology emphasizes that children in middle school have a limited ability to understand and counter persuasive intent. Advertising literacy, including the ability to identify advertisements, understand their sponsorship, and understand their selling intent, is acquired gradually throughout childhood. Young children cannot differentiate between content and embedded advertisements, and even older children might not fully grasp advertisers’ tactics. A systematic review identified that persuasion awareness and advertising literacy are not yet well developed until adolescence. This phase of development means that children do not have the critical thinking ability and executive function to knowingly undo marketing attempts. Even in older children who are able to recognize content as advertising, they might still be vulnerable to appealing content. Additionally, impulse control and self-control are still developing in children, so emotionally appealing or gamified advertising is especially persuasive. Traditional developmental theories indicate that it is only at 8–12 years that children start to comprehend advertising intent, with many of the subtleties not being grasped until older ages [7,8,9]. These are issues that are reflected in more current research; for instance, it is found that children between the ages of 9 and 11 can very likely identify food advertising in videos but still react positively since they like the content. This research emphasizes that awareness of an advert does not necessarily entail resistance [2,7]. With this context in mind, the current study is an examination of how middle school students view neuromarketing methods and television advertising within their online contexts. Particular focus is placed on how knowledge, interest, and ethical issues related to neuromarketing relate to advertising literacy, understood as persuasion knowledge and critical thinking, and how these, in turn, impact students’ behavioral intentions. By incorporating insights from developmental psychology, media literacy, and neuromarketing, the research seeks to offer empirical insights into children’s cognitive and emotional attitudes toward algorithmically driven persuasion.

The moral implications of this susceptibility are profound. Children’s developing competencies have particular safeguards necessary in marketing contexts. Children comprise a legally and ethically susceptible group, with a right to privacy and protection against exploitation [1,8]. In practice, nevertheless, the online marketing context habitually exploits children’s personal information and cognitive inexperience. Research suggests that most children’s websites and apps gather and disclose personal data—names, video, location, and use—without express consent. In one examination of child-targeted websites, for example, most gathered personal data, and a large percentage of those sites passed it along to third parties. This extensive data collection raises concerns about manipulative profiling and targeted persuasion [2,9].

Acknowledging these concerns, regulators have taken steps: in the United States, the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) limits data collection from children under 13 without parental consent, and the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) provides protection up to the age of 16, requiring child-friendly notices and additional restrictions, including a ban on profiling children [10]. Loopholes do exist, however, especially for teenagers, and some self-regulatory codes still allow data use with little supervision. Overall, online marketing to children is riddled with difficult ethical issues in manipulation, privacy, and fairness that require thoughtful attention.

Further complicating this environment is the advent of neuromarketing—the use of neuroscience instrumentation to investigate consumer decision-making processes [11]. Neuromarketing uses methods like functional MRI, EEG, eye-tracking, and biometric feedback to gauge consumers’ neural and physiological reactions to ads and brands. By quantifying stimuli that attract subconscious attention or emotional connection, marketers can craft content to be most effective [8,12,13]. Internet-based neuromarketing is formulated in terms of algorithmic personalization and targeted advertisement designs drawing from a knowledge base of what activates primal reward processes. Advertisements, for instance, can be tested for their ability to generate emotional arousal or brand association at the neural level. While supporters of neuromarketing argue that it broadens the scope of consumer behavior knowledge, these alternatives have ethical connotations when directed toward vulnerable populations [14,15].

Children’s distinctive neurocognitive profiles add to these worries. Although empirical neuromarketing research has largely been attentive to adults, preliminary evidence indicates that children’s brains are extremely sensitive to branding [14,15]. For example, in an fMRI study of children in elementary school, it was discovered that exposure to known food logos stimulated reward-associated brain areas, and it was a sign of the excessive influence of branding on the child brain. In spite of these findings, systematic research on children’s perception or resistance of sophisticated marketing techniques is limited. Scholars have urged more research on children’s neural and psychological reactions to marketing, considering its ubiquity. In brief, the development of neuromarketing techniques provides advertisers with unprecedented control, yet children have minimal defenses, so empirical insight into how school-aged children perceive or react to these unnoticed digital prompts to persuasion is essential [11,14,16].

Collectively, the literature reveals an evident gap. Although there is evidence to indicate that children are exposed to a deluge of screen-based advertisements and have emergent, and often limited, persuasion knowledge, there has been minimal research into middle school students’ understandings of contemporary persuasive strategies. In particular, children’s understanding of personalized or game-based advertisements presented on digital devices, and the degree to which they are aware of the marketing tactics used, is unknown. Moreover, most of the studies have been carried out in home or clinical environments, and little has been conducted in school environments [1,2,8]. In a school environment, educational website adverts or ads inserted into free online computer games can pose some specific challenges. As yet, there is no empirical research investigating children’s attitudes towards neuromarketing or the effects of exposure to screen advertising in a school environment on their enjoyment of persuasion. This literature gap means that important questions regarding children’s perceptions and media literacy development in the current digital landscape remain unanswered [1,2,8].

Building on this research gap, the present study investigates how middle school children perceive and react to AVPs based on the use of neuroadvertising and neuromarketing strategies in the educational context. More specifically, this study examines the connections between students’ advertising awareness (i.e., advertising recognition and understanding), interest in digital marketing content, and self-reported exposure to screen-based advertising and levels of their persuasion knowledge, advertising skepticism, and purchase intentions. This research also seeks to establish whether learners with more exposure to, or greater interest in, digital advertisements have greater advertising literacy and better critical evaluation skills, and, subsequently, are more desirous of the advertised items.

Accordingly, this study is guided by the following overarching research questions:

- RQ1: How do adolescents perceive and respond to neuromarketing-based and screen-based persuasive strategies in digital media environments?

- RQ2: What cognitive (e.g., persuasion knowledge) and attitudinal (e.g., advertising skepticism) factors mediate the effects of digital advertising exposure on purchase intentions?

These questions are examined through a structural equation model, operationalized by the specific hypotheses developed in Section 2.

The findings supported the majority of the postulated associations. Knowledge and Awareness of Neuromarketing (NAK) and Exposure to Screen-Based Advertising (SBA) were significant predictors of Purchase Intentions (PIs), and Interest in Neuromarketing (NEI) had no immediate effect. Persuasion Knowledge (PK) and Advertising Skepticism (AS) were both positive drivers of PIs. Mediational analyses indicated that PK and AS partially mediated NAK and SBA effects on PIs, and NEI only had an indirect effect on PIs through AS. Multi-group analyses confirmed strong age-based, past neuromarketing exposure-based, ad-click-based, and advertising literacy education-based moderating effects. Young adolescents were more cognitively resistant (e.g., NAK on PK), but older adolescents were more behaviorally responsive to online exposure (e.g., SBA on PI). The non-educated and unaware students were more susceptible to influence, but the students with prior media literacy training were better equipped with persuasion knowledge and skepticism. These results validate the intricate interaction between cognitive, emotional, and developmental processes employed in adolescents’ use of persuasive digital media.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows: Section 2 outlines neuromarketing and advertising literacy research. Section 3 introduces the conceptual model and hypotheses. Section 4 describes the methodology and data collection as well as analysis techniques. Section 5 displays SEM results, including direct, mediating, and group-specific effects. Section 6 presents practical implications. Section 7 concludes with the main findings and suggestions for future work.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Digital Persuasion and Neuromarketing in Advertising to Children

Interdisciplinary scholarship from across the social sciences coalesces around the powerful, if ethically dubious, impact of neuromarketing and affectively appealing advertising on children and adolescents. Al Abbas et al. [17] refer to the twin possibilities of neuromarketing producing positive and manipulative advertisement impacts, particularly on children, a population generally assumed to be cognitively vulnerable. Their conceptual difference between intended and unintended effect is a useful typology, if one requiring empirical testing.

Rita et al.’s [18] eye-tracking and electrodermal activity experimental study shows that new advertising—particularly celebrity-free—elicits higher arousal and enjoyment, again predicting sharing intention. It indicates that novelty and affective intensity are key mediators of persuasive effect, a result of especially high significance in digital contexts for kids. Simultaneously, Molinillo et al. [19] investigate the drivers of mobile casual game adoption by using structural equation modeling and discover that user interaction and social network impact indirectly influence behavioral intentions through hedonic and utilitarian motivations. This model is not child-centered but provides the rationale for how emotionally engaging elements of design precipitate deeper engagement, which can be translated directly to gamified advertising and neuromarketing-driven persuasive systems in children’s apps. Complementing and supplementing these results, Vrtana et al.’s [20] psychophysiological experiment verifies that affective advertising appeals shape teenagers’ moods and emotional states, differing by region but not gender. This research reveals the affective strength of narrative-type advertising and its possible difference across demographic subgroups.

The broader ethical context of neuromarketing is summarized in UNICEF’s (2019) report [10], which cautions against the deployment of neuro-based persuasion techniques on children, citing developmental asymmetries and the lack of cognitive safeguards. The report highlights that neuromarketing bypasses rational evaluation and instead exploits unconscious emotional and attentional pathways—precisely those that remain underdeveloped in children. It also identifies a regulatory vacuum and calls for restrictions on these practices in youth-directed content.

Synthesizing these contributions yields several super-ordinate themes. First, throughout empirical and conceptual contributions, there is significant evidence that emotional intensity—whether it is generated by visual novelty, narrative resonance, or neuro-targeted appeals—serves a central role in facilitating the persuasiveness of messages. Second, children and adolescents, as a consequence of developmental constraints on persuasion knowledge and executive function, are particularly susceptible to these emotionally arousing stimuli [17,19]. Third, although experimental and modeling methodologies (e.g., SEM, eye-tracking, and arousal measurement) provide sound data on the processes of digital persuasion, empirical research specifically targeting neuromarketing in educational or developmental settings is conspicuously lacking.

There is a substantial knowledge deficit in applying neuromarketing principles to education in advertising literacy. Academic curricula for the majority of teaching and interventions remain focused on traditional practices of advertisement and do not cover hidden, biometrically driven approaches that pervade mobile and digital space. Furthermore, there are no standardized psychometric scales or observational studies that measure the extent to which children deduce and react to neuromarketing messages in themselves—hindering the transferability of theory and pragmatic applicability [17,19]. With regard to strengths, the literature discussed here offers growing methodological sophistication (e.g., the application of neuroscience methods, SEM, and comparisons across regions), but much research is disconnected from developmental and educational theories.

Therefore, while current research identifies neuromarketing and emotional appeal as strongly determining young consumers’ reactions, it also reveals an important theory-driven child consumer research blind spot. Future studies will need to fill this gap by empirically investigating how neuromarketing influences children’s cognitive development, emotion regulation, and consumer socialization—preferably within naturalistic school settings that foster critical resistance to online persuasion. Based on the literature indicating a powerful influence of neuromarketing stimuli and children’s cognitive susceptibility, the following direct hypotheses are proposed:

H1.

Neuromarketing Awareness and Knowledge (NAK) will have a positive direct effect on Purchase Intentions (PIs).

H2.

Screen-Based Advertising Exposure (SBA) will have a positive direct effect on Purchase Intentions (PIs).

H3.

Interest and Engagement with Neuromarketing (NEI) will have a positive direct effect on Purchase Intentions (PIs).

2.2. Advertising Literacy in Middle School Children

The research demonstrates the rich and multifaceted nature of children’s and adolescents’ advertising literacy in the digital era. Holiday et al. [21] illustrates how parents actively mediate access to advertisement when they feel personalized advertisement is powerful, especially when they believe their children are likely to be targeted with the same. This was an important instance demonstrating the role of parent perception towards indirectly forming advertising literacy. Holvoet et al. [22] takes this further by demonstrating that parents of adolescents feel a heavy obligation to moderate access to targeted advertisement, in particular when data protection and media literacy concerns are most acute. These studies report the same picture: parental mediation is an influential socialization factor that is dependent on advertising appropriateness attitudes and child vulnerability.

Rauwers et al. [23] contribute by investigating the effect of creative media adverts. Although not designed for children, the study assumes processes such as humor and value perception that can be applied to children, particularly in converged advertainment programs. Fernández-Gómez et al. [24] determine that addressable TV adverts strengthen children’s sense of belongingness and resulting purchase requests, usually underappreciated by their parents. In the same vein, Borchers et al. [1] offer a qualitative examination of parent–child interaction in active mediation where dynamic and sometimes even reversed roles are attained, in which children execute advertising literacy in informing parents on media logic.

Panackal et al. [25], in a bibliometric analysis of consumer socialization research, find continued resonance in studying children’s acquisition of consumption attitudes. As a corollary, a study by Feijoo et al. [26] concludes that older children are more aware of influencer-based content but tend to react with apathy. The result implies an advertising literacy development trajectory, moderated by habituation and perhaps desensitization.

Van Berlo et al. [27] highlight the role of smartphone attachment and brand awareness in the familiarity of adolescents toward advergames. Not surprisingly, even greater smartphone attachment enables the recognition of advergames but does not necessarily decrease advertisement susceptibility, which suggests a possible gap between behavior susceptibility and cognitive resistance. Wang et al. [6] test direct measures of persuasion knowledge in young children and conclude that although source recognition is a good conceptual literacy measure, some measures fail to locate expected correlations, and this is most likely due to developmental and measurement limits.

Feijoo et al. [26] corroborate, in a distinct manner, body image issues among adolescents as associated with advertising literacy. Her research indicates greater advertising literacy to undo negative self-concepts of bodies and negative self-concepts of bodies caused by influencer posts, proving advertising literacy to have protective properties in addition to purchase behavior. Lastly, Holvoet et al. [28] reaffirm parental concern and competence after privacy literacy and attitudes regarding ads forecast attempts at mediation, proving social context to have a significant impact on children’s advertising experiences.

Together, these studies offer strong empirical and theoretical evidence for the dual advertising literacy dimensions—conceptual and attitudinal, albeit as important moderators of children’s reactions to persuasion messages [22,28,29]. They also substantiate standardized scales like the CALS-c and AALS-c in studies of advertising influence on electronic media. Despite solid evidence on literacy development benefits and parental engagement, there are knowledge gaps in the effects of new forms of digital ads such as advergames and influencer posts on literacy levels among children. There are also some discrepancies found—e.g., familiarity not always resulting in questioning or rejection—implying that subsequent research would be aimed at exploring the mediating mechanisms and context moderators (e.g., discussion among family, digital literacy education, and affective vulnerability) that condition these processes [23,27,30]. This research draws on such findings by using SEM to examine a complex model with neuromarketing sensitivity, advertising exposure, persuasion knowledge, and critical thinking in trying to develop a balanced framework of the psychological and social foundations of advertising literacy in early adolescence. Drawing on the evidence for conceptual and attitudinal advertising literacy as key resilience factors, the following hypotheses are proposed to test their direct and mediating effects:

H4a.

Persuasion Knowledge (PK) will have a positive direct effect on Purchase Intentions (PIs).

H4b.

Advertising Skepticism (AS) will have a positive direct effect on Purchase Intentions (PIs).

H5a.

Persuasion Knowledge (PK) mediates the relationship between Neuromarketing Awareness and Knowledge (NAK) and Purchase Intentions (PIs).

H5b.

Advertising Skepticism (AS) mediates the relationship between Neuromarketing Awareness and Knowledge (NAK) and Purchase Intentions (PIs).

2.3. Screen-Based Advertising and Materialism

An expanding field of literature has drawn attention to the effect of screen-based advertising on the consumer behavior and materialistic values of children, an effect exacerbated by today’s digital environments, which are replete, engaging, and frequently hidden environments for advertising. Research has repeatedly demonstrated how children’s media use, especially on sites such as YouTube, educational apps, and mobile games, exposes children to embedded marketing like advergames and influencer endorsements that undermine the entertainment/advertising divide [31]. This aligns with findings by Rincón-Gallardo Patiño et al. [32], who demonstrated that the majority of food advertisements on Mexican television did not meet nutritional standards and targeted children with high-energy, high-sugar content, emphasizing the potential for negative health and consumption outcomes.

The magnitude of children’s screen use has been more fully explicated by Pyne et al. [33], who delineated parenting styles and home screen management practices as essential moderators. Authoritarian parenting was associated with less child screen time, whereas permissive or neglectful styles were conducive to overexposure. Likewise, Santos et al. [34] validated that greater screen time is associated with attention issues, strengthening alarm regarding the cognitive cost of extensive digital media use during the early years. Materialism is one of the most important psychological concepts mediating children’s sensitivity to advertising. Opree et al.’s [35] Material Values Scale for Children (MVS-c) is still a validated scale for assessing the contribution of materialism to predicting children’s brand choices and purchase intentions. Demers-Potvin et al. [36] illustrated its applicability to SEM models for indicating that kids with high material centrality are more vulnerable to persuasive digital content. Ahn et al. [37] corroborate this by pointing out adolescents in minority groups already have advanced persuasion knowledge yet are still in need of developing more coping strategies—indicating that even high exposure cannot assure resistance.

A few other researchers have examined screen-based consumption psychosocial processes. Tan et al. [38] identified parent–child shared screen use and household device availability as strong predictors of preschoolers’ screen time behavior, again pointing to environmental impacts on media-related behavior. At the same time, Demers-Potvin et al. [36] stated that teenagers in six nations spent more than 7–10 h a day in front of screens and were habitually exposed to unhealthy food ads, especially on social media. Exposure was considerably linked with liking sugary drinks and fast food, which has policy relevance worldwide.

Critically, although screen advertising and materialism have been examined separately, there have been few attempts to synthesize these constructs within a higher-order developmental model. The literature is largely descriptive and correlational (e.g., length of exposure, frequency of exposure), without paying attention to enduring underlying values or mediating processes. Moreover, even though tests such as the MVS-c are increasingly well validated, their application to informing research on influencer-based or algorithm-driven ads is yet to be realized [31,32,34].

Collectively, the literature portrays a strong association between children’s exposure to screen-based advertising and increased materialistic values, particularly where advertising literacy is low. The confluence of a high frequency of exposure, an immersive format, and underdeveloped cognitive defenses creates a compelling context for shaping consumer identity and behavior [33,39,40,41]. Additional research is warranted to follow integrative, longitudinal, and model-based research designs—such as SEM—to investigate how screen exposure, materialism, and literacy covary over time in enhancing children’s digital consumer development.

This research suggests a conceptual model in which middle schoolers’ exposure to online persuasion—screen advertisements and neuromarketing content—is related to their purchase intentions. The model consists of three antecedents: neuromarketing interest, familiarity with the neuromarketing concept, and frequency of exposure to screen advertisements. These are hypothesized to affect purchase intentions directly and indirectly via two mediators: persuasion knowledge and ad skepticism. The Persuasion Knowledge Model [42] explains how children’s cognitive and attitudinal responses define vulnerability to persuasive communication. Incorporating neuromarketing-specific theory and the school environment context, the research provides novel understanding of how new forms of persuasive communication co-develop with early adolescence cognitive maturation and media exposure. To integrate exposure-related cognitive vulnerability with materialism research, and test how online advertising and neuromarketing interest exert their influence through literacy mechanisms, the following hypotheses are examined:

H6a.

Persuasion Knowledge (PK) mediates the relationship between Screen-Based Advertising Exposure (SBA) and Purchase Intentions (PIs).

H6b.

Advertising Skepticism (AS) mediates the relationship between Screen-Based Advertising Exposure (SBA) and Purchase Intentions (PIs).

H7a.

Persuasion Knowledge (PK) mediates the relationship between Interest and Engagement with Neuromarketing (NEI) and Purchase Intentions (PIs).

H7b.

Advertising Skepticism (AS) mediates the relationship between Interest and Engagement with Neuromarketing (NEI) and Purchase Intentions (PIs).

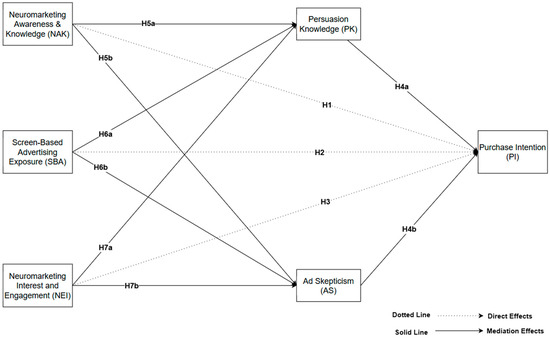

Figure 1 presents the conceptual model advanced herein, specifying both direct and indirect (mediated) influences from Neuromarketing Awareness (NAK), Screen-Based Advertising Exposure (SBA), and Neuromarketing Interest (NEI) on Purchase Intentions (PIs). Persuasion Knowledge (PK) and Ad Skepticism (AS) are two thought mediators, specifying a child’s resistance processes with respect to digital persuasion. Dotted arrows show direct effects; solid arrows show mediated paths.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Conceptual Model and Rationale

The growth of screen advertising across the digital media consumed by children—including YouTube, apps, and educational software—has prompted urgent questions regarding the competencies of child audiences to identify, analyze, and resist persuasive messages, especially when those messages rely on brain-science-based tactics [33,34]. Early adolescent middle schoolers (ages 12–15) are especially vulnerable to more interactive and targeted advertising content that is not always overt. Although there is the increased application of neuromarketing principles to online advertising, empirical studies on children’s perception and acceptance of these attempts are inadequate [3,4]. This research bridges this knowledge gap by combining neuromarketing-specific concepts with existing advertising literacy and consumer behavior models, providing theoretical and practical contributions to the areas of media literacy, marketing ethics, and educational psychology.

There are three primary independent variables in the conceptual model of this study: Neuromarketing Awareness and Knowledge (NAK), Interest and Engagement with Neuromarketing (NE), and Exposure to Screen-Based Advertising (SBA). These constructs capture different dimensions of adolescents’ exposure and cognitive involvement with persuasive content in the digital context [13,43,44]. NAK assesses students’ know-how about the neuroscience-informed approaches to advertising, e.g., eye-tracking or emotional targeting, and NE assesses the interest and enthusiasm about such approaches. SBA assesses how often and in what contexts students are exposed to persuasive ads on online platforms like YouTube or mobile gaming—platforms where embedded marketing is prevalent but frequently imperceptible [5,45].

Two mediating variables—Persuasion Knowledge (PK) and Advertising Skepticism (AS)—are posited to account for the way in which students’ understanding of persuasive intent (PK) and skepticism regarding advertisement claims (AS) affect the behavioral outcome of Purchase Intentions (PIs). PK is reflective of children’s conceptual literacy—their ability to identify persuasion tactics—whereas AS is indicative of their attitudinal literacy or inclination to distrust advertising truthfulness [46,47]. It is established through research that heightened PK and AS can act as mental defenses, which render a person less susceptible to ads [45]. These defenses are still not well developed among adolescents, and, thus, they are a susceptible group in neuromarketing.

By incorporating these constructs, this model offers a high-resolution account of how teenagers cognitively and emotionally process online persuasion. The model is tested using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), which is ideally suited to model latent constructs and both direct as well as indirect effects. The application of validated measures like the CALS-c, AALS-c, and MVS-c also guarantees the reliability of constructs under examination [46,47].

Finally, this research adds to the theoretical knowledge of adolescent advertising literacy in the era of neuromarketing and has applied significance for educators, policymakers, and online content creators. As schools move to incorporate more digital media, a grasp of the manner in which children make sense of embedded marketing—particularly neuroscientifically driven approaches—is paramount in supporting ethical media spaces and improving digital literacy education [46,47].

3.2. Data Collection and Sampling

The current research used a quantitative cross-sectional survey design, which was suitable for examining the impact of middle school students’ exposure to neuromarketing, exposure to persuasive advertisements, and exposure to screen-based advertisements on their persuasion knowledge, advertising skepticism, and purchase intentions. The cross-sectional design allowed for collecting information at a single moment in time in a real learning setting and thereby provided a snapshot of cognitive and attitudinal processes related to digital persuasion [48,49].

Participants were recruited from Arsakeia–Tositseia Schools, a private school network in Greece, and data collection was carried out in class groups. The chosen school network is an educationally diversified, city-based population, where students come from a large coverage area in Patras, including inner and periphery areas. Arsakeia–Tositseia Schools provide a combination of conventional and computer-aided curricula; thus, students are continuously exposed to formal education content and screen media. The student population is socioeconomically diverse, with middle- and upper-middle-class students—groups that are themselves typically the first to be targeted by online marketing efforts. In addition, the schools’ high levels of digital provision and early technology adoption make them a suitable context in which to study children’s uses of algorithmic and neuromarketing-influenced content. While private, the school network is pedagogically consistent and in strong alignment with the national curriculum, and its users follow digital habits and media literacy profiles comparable to national averages on the basis of recent surveys of Greek teenage media consumption [48,49]. The target population was 12- to 15-year-old students, an age group selected to provide a sufficient range of digital media exposure and familiarity with advertising, and also represent the phase of cognitive development at which they can respond to attitudinal and perception-based inquiries. Specifically, students from Grades 6 to 9, covering early to middle adolescence years, were recruited. Our aim was to have a wide age range in order for a sufficient and developmentally suitable sample for SEM.

A purposive sampling strategy was employed, and target classrooms were chosen where students would likely satisfy the inclusion criteria [50,51]. Although this non-probability strategy reduces wide generalizability, it did allow differential access to students of suitable cognitive maturity to complete surveys and ensured school staff cooperation. The final sample of 244 students was achieved, as demanded by general SEM requirements for the minimum sample size—specifically when applying SmartPLS, which supports complex models with smaller sample sizes compared to covariance-based methods. According to the 10-time rule for PLS-SEM (10 cases per indicator for the most complex construct), the sample is methodologically sufficient [52,53].

Questionnaires were administered in the latter part of the school year within the context of normal class lessons. Researchers explained the aim of the research to students in a way appropriate to their age and stressed the voluntary, confidential nature of participation. Instructions were delivered in writing as well as verbally.

Data were collected by using a paper survey, completed in normal class time, under the supervision of teachers and researchers. Respondents were instructed to answer based on their previous experiences with online advertisements, as received on educational apps, video games, and websites like YouTube and TikTok. Completion time was around 20–25 min. A research assistant was available to explain any phrasing as necessary to help comprehension, and instructions were standardized across classrooms. The final instrument contained 21 items across 6 constructs (Appendix A, Table A1), measuring students’ experience and perception with digital advertising and neuromarketing. To further reduce response bias risk, students were specifically told that there were no right or wrong answers and were urged to respond candidly from their genuine opinions and experiences. Survey anonymity was stressed, and no identifying data were gathered. No teacher reviewed responses, and item wording was neutral and non-judgmental to limit social desirability bias. There was also the inclusion of an attention-check question to make sure students were reading questions thoroughly and answering reflectively. These were carried out to make sure that the students were comfortable and unbiased in filling out the questionnaire.

For content validity and to ensure the appropriateness of the reading level of the content, the instrument was modified from previously validated measures and also pilot-tested on a small sample of students (n = 50) from the same school district. Some adjustments to language simplicity and wording were made according to this feedback. No reverse-scored items were included in order to prevent ambiguity and ensure reliability.

Ethical precautions were strictly adhered to. Parents received comprehensive information sheets and were asked to return signed consent forms. Verbal or written assent was also obtained from the students prior to participation. Participation was confidential, anonymous, and purely voluntary, with an opt-out procedure available at every level. The study protocol received approval from the University of Patras’s competent ethics committee.

Questionnaires were returned completed and marked with an anonymous ID number (names and personal information were not noted). Data were input into a secure password-protected database. All data handling was compliant with privacy law (e.g., GDPR) and university policy. Parents were informed of an opt-out period: parents had up to one week following data collection to withdraw their child’s data, in accordance with the approved ethics protocol.

3.3. Measurement Scales

The completed survey questionnaire consisted of five tested constructs adapted to measure awareness, attitude, and behavioral responses of middle school students towards screen-based advertising and neuromarketing.

First, Neuromarketing Awareness and Interest (NAK) was measured through items adapted from Bilgin Turna [12] and Eser et al. [13], addressing students’ familiarity with neuromarketing and their curiosity about its role in advertising. Sample items included “I know that some researchers study how people’s brains react to ads” and “In the future, I want to learn more about how neuromarketing works”. Interest and Engagement with Neuromarketing (NEI) was measured thorough a 4-item scale from Bilgin Turna [12] and Eser et al. [13], addressing students’ interest and engagement with neuromarketing techniques and technologies and their role in advertising.

Second, Persuasion Knowledge (PK) was assessed using adapted statements from the CALS-c [45], emphasizing students’ conceptual understanding of how advertising uses emotional or cognitive strategies to persuade. Items such as “I understand that ads try to be funny because it activates emotions and makes the product more memorable” reflect children’s grasp of strategic messaging. Third, Advertising Skepticism (AS), drawn from the AALS-c [45], captured students’ critical stance toward advertisements through statements like “I don’t always trust what screen ads say about their products”.

Fourth, Screen-Based Advertising Exposure (SBA) was operationalized using child-adapted self-report statements grounded in the SCREEN-Q framework [47]. Items reflected contextually relevant media habits, including “I often see ads while watching YouTube or playing games”, “Sometimes I see ads while doing schoolwork on a tablet or computer”, and “I notice ads when using my phone or my parents’ phone”. These items were designed to capture the frequency and situational presence of digital advertising in students’ everyday screen interactions.

Finally, Purchase Intentions (PIs) were measured using adapted items from [43], including “Sometimes I really want something just because the ad made it look cool or special”. All items were measured on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), with age-appropriate language and visuals to support comprehension.

3.4. Sample Profile

The final sample comprised 244 middle school students aged 12 to 15 years (M ≈ 13.1). Gender was balanced, with 48.8% being girls and 51.2% being boys (Table 1). The most represented age group was 12 years (30.7%), followed by 13 (26.6%), 15 (23.0%), and 14 (19.7%). Regarding class level, 36.5% were in Grade 6, 33.2% in Grade 7, 17.2% in Grade 8, and 13.1% in Grade 9. In terms of digital access, 34.0% owned a personal device, 28.3% shared a family device, and 37.7% had no personal access. Daily screen time for non-school activities was 1–2 h for 32.4%, 2–3 h for 24.2%, and more than 3 h for 21.3%; 22.1% reported less than 1 h per day. The most common ad exposure platforms were games (24.2%), apps (21.3%), YouTube (17.6%), and TV (14.8%). Only 30.7% had clicked or interacted with an ad, while 36.9% had not, and 32.4% were unsure. Regarding advertising education, 34.4% recalled learning about advertising or media in school, while 37.3% had not, and 28.3% were unsure. Only 13.9% felt they understood advertising strategies very well, while 33.6% indicated limited understanding, and 23.0% reported none at all. Lastly, 18.0% had heard of “neuromarketing” before the survey, with 59.8% indicating no prior awareness.

Table 1.

Sample profile.

4. Data Analysis and Results

Data analysis was performed with SmartPLS 4 (version 4.1.0.0) using structural equation modeling (SEM) as the core method. SEM, specifically its variance-based type, is most often used for estimating complex causal relationships in social science and management research contexts [54]. PLS-SEM was selected because of its appropriateness in predicting the variance of dependent latent constructs and its capability in managing models with comparatively small to moderate sample sizes as well as non-normal data distributions [55,56]. Multi-group analysis (MGA) was utilized for measuring structural differences between subgroups, facilitating the assessment of interaction effects usually overlooked by conventional regression methods [57,58,59]. Analysis proceeded according to the procedural guidelines of Wong [60], such as employing bootstrapping (10,000 resamples) to determine significance. Examination of the reflective measurement model relied on outer loadings of greater than 0.70 to provide construct validity and indicator reliability.

4.1. Common Method Bias (CMB)

To assess the reliability and validity of the findings, CMB was tested using the procedure established by Podsakoff et al. [61]. Harman’s single-factor test was used to determine whether variance structure was being dominated by a single factor. Unrotated principal component analysis indicated that the first largest factor captured merely 34.459% of the variance total—far below the frequently applied 50% criterion. Whereas CMB did not seem to be a significant problem in this research, handling it makes the credibility of the variable relationships observed higher and less likely to be influenced by bias [61,62].

4.2. Measurement Model

The first phase of the PLS-SEM process is measurement model evaluation, and reflective indicators are used to test the constructs. Testing is performed according to Hair et al. [55], and composite reliability, indicator reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity tests are used.

Indicator reliability is, as per Vinzi et al. [63], the degree to which the variance in an item is explained by the construct. This is typically measured in terms of the outer loading values, ideally above 0.70, as recommended by Wong [60] and Chin [64]. Vinzi et al. [63] do comment, however, that within the social sciences discipline, some of the measures will necessarily be lower than such a figure. Decisions on item deletion in such an instance should be on whether item deletion raises overall composite reliability or convergent validity. As proposed by Babin et al. [54], loadings of 0.40–0.70 are indicators that must be retained unless their removal significantly improves either the composite reliability or average variance extracted (AVE) of the construct. On the basis of the recommendations given by Gefen et al. [65], as can be obtained from Table 2, indicator AS4 was excluded from the measurement model of this research since its outer loadings were less than the cut-off value of 0.500.

Table 2.

Factor loading reliability and convergent validity.

This study relied on Cronbach’s alpha, rho_A, and composite reliability to determine its reliability. With a threshold of at least 0.70 recommended by Wasko et al. [66], constructs like AS, NAK, NEI, PI, PK, and SBA were internally consistent. The other constructs also showed at least moderate to high reliability, consistent with earlier research [55,56]. The rho_A coefficient, theoretically placed between Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability, was above 0.70 in the majority of cases, further validating the reliability findings upheld by Hair et al. [56] and Vinzi et al. [63].

Convergent validity was established as the majority of constructs recorded an average variance extracted (AVE) level higher than the suggested 0.50 level, according to Fornell et al. [67]. For constructs with AVE values less than 0.50, convergent validity was still deemed acceptable if their composite reliability was above 0.60, according to Fornell’s recommendations. Inter-construct correlation analysis also attested to the discriminant validity that made the correlation of each construct with others less than the square root of its own AVE. The HTMT ratio of correlations also corroborated the study at all values less than the conservative value of 0.85 as proffered by Henseler et al. [68], as presented in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

HTMT ratio.

Table 4.

Fornell and Larcker criterion.

4.3. Structural Model

The structural model of the proposed model was evaluated in terms of R2 and Q2 values, along with the significance of the path coefficients following the approach recommended by Babin et al. [54]. In the present study, the R2 values were 0.447 for Purchase Intentions (PIs), 0.228 for Advertising Skepticism (AS), and 0.354 for Persuasion Knowledge (PK)—that is, satisfactory explanatory power as all the values fall between 0 and 1. Furthermore, the model was demonstrated to have moderate to high predictive significance, where Q2 measures were 0.354 for Purchase Intentions (PIs), 0.200 for Advertising Skepticism (AS), and 0.330 for Persuasion Knowledge (PK).

Model fit was also substantiated by hypothesis testing, which verified the relevance of the relationships among constructs. Path coefficients were estimated based on the bootstrapping procedure, as advised by Hair et al. [56]. Mediation effects were analyzed by a one-tailed, bias-corrected bootstrapping procedure based on the process outlined by Preacher and Hayes [68] and Streukens et al. [69], with the use of 10,000 bootstrap samples. Table 5 presents an elaborate overview of these outcomes.

Table 5.

Hypothesis testing.

The structural model was tested through PLS-SEM. Bootstraping for 10,000 resamples was carried out to test direct path coefficient significance. Table 5 depicts all the hypothesized relationships as the result from standardized coefficients (β), standard deviation, t-values, p-values, and significance levels. As was hypothesized, Neuromarketing Awareness and Knowledge (NAK) significantly influenced Purchase Intentions (PIs) (β = 0.313, SD = 0.059, t = 5.27, p < 0.001), supportive of H1. Likewise, Screen-Based Advertising Exposure (SBA) predicted Purchase Intentions as well but with minimal effect size (β = 0.130, SD = 0.068, t = 1.92, p = 0.027), supportive of H2. In contrast to the proposed hypothesis, Interest and Engagement with Neuromarketing (NEI) did not have a significant direct correlation with Purchase Intentions (β = 0.024, SD = 0.053, t = 0.444, p = 0.328); H3 was not supported. As for the mediators, Persuasion Knowledge (PK) predicted Purchase Intentions significantly (β = 0.183, SD = 0.062, t = 2.945, p = 0.002), hence H4a was supported. In addition, Advertising Skepticism had a strong positive influence on Purchase Intentions: β = 0.246, SD = 0.064, t = 3.824, p < 0.001, thereby confirming H4b.

4.3.1. Mediation Analysis

To examine the mediating role of Persuasion Knowledge (PK) and Advertising Skepticism (AS) in the relationship between the independent variables and Purchase Intentions (PI), a bias-corrected bootstrapping procedure with 10,000 resamples was employed. Table 6 presents the specific indirect effects and their corresponding statistical values.

Table 6.

Mediation analysis.

Neuromarketing Awareness and Knowledge (NAK) indirectly had a significant effect on Purchase Intentions through both Persuasion Knowledge (β = 0.055, SD = 0.025, t = 2.241, p = 0.013) and Advertising Skepticism (β = 0.040, SD = 0.019, t = 2.107, p = 0.018), which supported H5a and H5b. Since the direct effect between NAK and PIs remained significant, these indicate partial mediation. For Screen-Based Advertising Exposure (SBA), both Persuasion Knowledge (β = 0.069, SE = 0.027, t = 2.527, p = 0.006) and Advertising Skepticism (β = 0.087, SD = 0.030, t = 2.902, p = 0.002) were also found to significantly mediate the relationship with Purchase Intentions, confirming H6a and H6b. These results again indicate partial mediation, as the direct effect of SBA on PIs remained significant. Against that, Interest and Engagement with Neuromarketing (NEI) did not exhibit a significant indirect effect through Persuasion Knowledge (β = –0.006, SE = 0.012, t = 0.460, p = 0.323); H7a was not supported. However, a significant negative indirect effect through Advertising Skepticism was viewed through the prism of relationships with β = –0.040, SE = 0.021, t = 1.906, and p = 0.028; H7b was supported. As the direct effect of NEI on PIs was not significant, the finding indicates full mediation through AS.

4.3.2. Multi-Group Analysis (MGA)

A multi-group analysis was conducted in SmartPLS to examine if structural relations were different between subgroups of demographics, experiences, and cognition. Path coefficient differences among groups pertaining to age, history of advertising exposure, prior experience with advertising literacy education, and awareness regarding neuromarketing were examined. Differences are considered statistically significant at p < 0.05 (Table 7).

Table 7.

Significant MGA results with group comparisons.

Age-related differences emerged in multiple relationships. The path from Neuromarketing Awareness to Persuasion Knowledge (NAK → PK) differed significantly between ages 12 and 13 (Δβ = −0.463, p = 0.008) and between ages 13 and 14 (Δβ = 0.336, p = 0.037), while Screen-Based Advertising Exposure to Persuasion Knowledge (SBA → PK) also varied between ages 12 and 13 (Δβ = 0.404, p = 0.018). The path from Persuasion Knowledge to Purchase Intentions (PK → PIs) differed between ages 13 and 14 (Δβ = −0.436, p = 0.017) and ages 12 and 13 (Δβ = 0.317, p = 0.033), suggesting developmental changes in the cognitive influence on behavior. Similarly, neuromarketing engagement to Purchase Intentions (NEI → PIs) differed across ages 13 vs. 15 (Δβ = −0.356, p = 0.029), ages 14 vs. 15 (Δβ = −0.338, p = 0.026), and ages 12 vs. 14 (Δβ = 0.226, p = 0.047), indicating the declining influence of engagement with age. Screen-Based Advertising to Purchase Intentions (SBA → PIs) differed across ages 12 vs. 15 (Δβ = 0.406, p = 0.009), 13 vs. 14 (Δβ = 0.462, p = 0.009), and 13 vs. 15 (Δβ = 0.634, p = 0.001), while Advertising Skepticism to purchase intentions (AS → PIs) was significant between ages 12 and 15 (Δβ = −0.293, p = 0.036) and marginally between 14 and 15 (Δβ = −0.311, p = 0.053). NEI → AS also differed between ages 12 and 15 (Δβ = 0.305, p = 0.046).

Regarding advertising interaction history, significant differences emerged between students who had and had not clicked on ads. NAK → AS (Δβ = −0.295, p = 0.039) and SBA → PIs (Δβ = −0.271, p = 0.045) were both stronger among non-clickers, while NEI → PK (Δβ = 0.267, p = 0.053) and SBA → AS (Δβ = −0.325, p = 0.026) differed between clickers and those who were unsure. Advertising literacy education moderated multiple effects. NAK → AS was stronger in students without exposure compared to those unsure (Δβ = −0.315, p = 0.030), while SBA → PK was stronger in students with exposure (Δβ = 0.281, p = 0.042). NEI → PIs (Δβ = 0.222, p = 0.046) and NEI → PK (Δβ = −0.306, p = 0.016; Δβ = −0.243, p = 0.044) also varied based on educational history, supporting the role of media literacy in developing cognitive defenses. Finally, prior awareness of neuromarketing significantly moderated several effects. SBA → PIs was stronger among those who had heard of neuromarketing (Δβ = 0.323, p = 0.025), as was AS → PIs (Δβ = −0.299, p = 0.026) and PK → PIs (Δβ = −0.226, p = 0.049). Additionally, SBA → PK was stronger in students with no awareness compared to those unsure (Δβ = 0.437, p = 0.018).

It has been demonstrated that age, advertising interaction behavior, literacy education, and prior neuromarketing awareness significantly moderate the strength of key psychological and behavioral pathways in the model. There is a tendency for younger students to show stronger resistance and skepticism, while older students are more behaviorally responsive to ad exposure. In addition, advertising literacy and prior awareness seem to support the development of persuasion knowledge and critical thinking. The remaining paths did not exhibit statistically significant differences across groups.

5. Discussion

This study investigated how middle school students’ exposure to screen-based advertising and neuromarketing-related experiences influence their purchase intentions through cognitive and attitudinal mechanisms [43,70,71]. The model integrated direct and mediated effects of Neuromarketing Awareness and Knowledge (NAK), Screen-Based Advertising Exposure (SBA), and Interest in Neuromarketing (NEI) on Purchase Intentions (PIs), with Persuasion Knowledge (PK) and Advertising Skepticism (AS) serving as mediators. Multi-group analyses further explored how age, digital behavior, educational exposure, and prior awareness moderated these relationships.

5.1. Direct Effect Results

The most significant direct impact was from Neuromarketing Awareness and Knowledge (NAK) to Purchase Intentions (PIs), reinforcing H1. This result expresses a paradoxical relationship in persuasion literacy: even though increased awareness of marketing strategies is intended to encourage resistance, it also improves perceived message relevance, particularly when adolescents receive the same messages as individualized or sophisticated. This would be consistent with earlier research showing that conceptual advertising literacy, or the ability to decode the motivation and strategy of advertising, will not, in itself, be followed by a resistance to arguments [4,22,28,45]. Especially in the case of digital and algorithmic personalization, students might perceive messages influenced by neuromarketing as credible, targeted, and relevant. That is, the detection of persuasive intent will not induce resistance but instead create a feeling of being personalized that further adds to the appeal and persuasiveness of the message [41,44,70,72].

Likewise, Screen-Based Advertising Exposure (SBA) had a positive influence on Purchase Intentions, although the effect size was smaller (H2 supported). This result accords with the mere exposure effect [72], since repeated exposure to a stimulus leads to more intense liking and familiarity independent of conscious awareness. For teenagers deeply engaged in screen-based cultures, repeated exposure to digital advertisements, be it on YouTube, video games, or social media, has the potential to legitimize and normalize consumer messages. Past research by [9,43,45] has found that the repeated viewing of branded content as part of programming leads to recalling and liking the brand name, particularly in the absence of or failure of disclosures. Therefore, although SBA is a less active mode of interaction than NAK, it also has an effect on buying behavior, possibly by way of heuristic processing and conditioning with repetition.

Conversely, Interest and Engagement with Neuromarketing (NEI) did not strongly directly impact PIs; H3 was not confirmed. This result indicates that basic curiosity or interest in neuromarketing—without the co-present conceptual knowledge—cannot be considered to be equivalent to behavioral intention. This would make it possible to have a dual-processing account of advertising effects: while elaboration cognition (e.g., NAK) has the potential to increase message receptivity by perceived relevance, affective involvement without thinking (e.g., NEI) might be insufficient on the basis of knowledge to affect intention [8,12,13,15,17]. It also emphasizes that advertising literacy is not homogeneous; affective involvement itself might not neutralize or augment persuasion unless it has more understanding of it. In addition, the conclusions of the present study are consistent with recent consumer behavior studies highlighting that youth purchase intentions are not only driven by message exposure but also by emotional responses, product perceived quality, and social influence. For example, current research shows that while product features, price, and reputation largely drive smartphone buying intent at uncertain times such as the COVID-19 pandemic, social influence does not necessarily appear as an overriding force [73]. In the same way, emotionally engaging content in electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) contexts enhances perceived quality and lowers purchase risk, consequently strengthening purchase intentions—though cognitive involvement (e.g., brand trust) is less significant [74]. Online opinion ratings and influencer credibility, as opposed to appeal, were stronger predictors of purchase intentions in beauty product contexts among young consumers [75]. These findings address our research by further confirming that the consumption reactions of adolescents are not merely cognitive processes but also experienced as a function of relevance, affective congruence, and trust of context, especially in virtual spaces where advertising surrounds them and is interactive.

The structural model also showed that Persuasion Knowledge (PK) and Advertising Skepticism (AS) both positively influenced Purchase Intentions (supporting H4a and H4b). Although existing literature routinely assumes PK and AS to be cognitive defenses [41,44,70], the direction of influences in the current study suggests a more involved development process. Instead of being obstacles to persuasion, PK and AS can be favorable to the persuasive effect when ads are understood by teens as normative, funny, or socially attractive. Teens with higher persuasion knowledge perhaps consider themselves more intelligent consumers and might utilize their judgment to respond selectively to advertising. Likewise, skeptics will still be purchased if the message is found to be entertaining or normative among peers, an age-dependent balance of resistance and acceptance [11,33,34].

Cumulatively, these results demonstrate that knowledge of persuasive techniques (NAK) and familiarity with Internet-based advertisement (SBA) enhance students’ sensitivity in behavior, as long as interest accompanied by knowledge (NEI) is lacking. Also, both PK and AS are not only defensive barriers, but also intellectual filters shaping message interpretation in complex ways, at times complementing buying intentions according to situation and developmental stage.

5.2. Mediation Analysis Results

The mediation analysis yielded new evidence for the psychological processes by which students’ knowledge, interest, and exposure to persuasive content affect their purchase intentions. The findings validated that Persuasion Knowledge (PK) and Advertising Skepticism (AS) are important mediators that validate most of the indirect hypotheses and fill some gaps in our knowledge regarding adolescents’ processing of online advertisements.

Specifically, both AS and PK moderately mediated the influence of Neuromarketing Awareness and Knowledge (NAK) on Purchase Intentions (PIs) (H5a and H5b confirmed). That is, awareness of manipulative strategies directly influences the intention of students to act but also triggers cognitive and attitudinal filters to influence the treatment of adverts. Such findings extrapolate the Persuasion Knowledge Model (PKM) in recognizing that advertising literacy is not merely a passive awareness of tactics but an active process that drives downstream effects [6,26,42]. When they acquire neuromarketing competencies, they not only become open to influence messages (if interpreted as personally relevant or high-tech), but also take evaluative positions—accepting or rejecting being persuaded on the basis of inferred purpose and consonance with personal values.

Additionally, Exposure to Screen-Based Advertising (SBA) revealed partial mediation via both PK and AS (H6a and H6b supported). This is in line with the assumption that online exposure to it provokes more than habituation; it demands thinking answers, whereby children not only learn about types of persuasiveness but also through emotional resistance. Such cross-path mediation effects are consistent with dual-process theories, which hold that exposure to ads triggers both heuristic and systematic processing, where PK and AS are the respective routes [44,46,47]. What is more, this also highlights that passive exposure provides latitude for learning and resistance, particularly in online environments where content is pervasive and highly personalized.

A rich and intriguing result was obtained in the Interest and Engagement with Neuromarketing case, where although it did not directly affect PIs, nor was suggested to indirectly affect significantly via PK (H7a not supported), it did have full mediation via AS (H7b supported). This implies a unique pathway: more engaged students with persuasive strategies are more critical, and this reduces their purchasing intentions. In contrast to NAK, which calls for both knowledge and involvement, NEI calls for more attitudinally defensive positioning, with interest in persuasion technologies perhaps leading to critical assessment and counteraction, rather than free spontaneity. This differential illustrates that knowledge without involvement does not necessarily mean purchasing behavior but rather can construct affective barriers against persuasion [41,47,70].

Together, these mediation results paint a more subtle picture of how teen consumers react to online persuasion. The partial mediation paths through NAK and SBA indicate that students do not react in the same way to persuasive material; their reactions are mediated by what they know and also by what they feel about advertising practices. In contrast, the full mediation of NEI by AS portrays a developmental setting in which interest generates skepticism, at least under conditions of a lack of critical conceptual knowledge.

5.3. Multi-Group Analysis

The multi-group analysis (MGA) indicated significant age, previous advertising and neuromarketing experience, and education-based moderating effects, supporting the contention that responses of adolescents to electronic persuasion are not homogeneous but heterogeneous and influenced by experience as well as development. Subgroup differences are informative about how persuasive operations are internalized and responded to according to varying cognitive and experiential profiles.

Age also functioned as a major moderator on some of the most significant paths. Adolescents aged between 12 and 13 years had much stronger effects of Neuromarketing Awareness and Knowledge (NAK) and Screen-Based Advertising Exposure (SBA) on Persuasion Knowledge (PK), and PK to Purchase Intentions (PIs). Such trends lend evidence to cognitive developmental models, whereby younger children are more mentally susceptible to the communication of advertising literacy and more likely to apply the principles learned, such as PK, into behavioral reasoning. By comparison, the older adolescents (14−15 years) showed more direct effects of SBA to PIs in keeping with transition from cognitive processing to increased experiential and affect-guided decision-making—a finding consistent with earlier work on adolescent media responsiveness [11,33,34].

Students’ prior instructional experience in advertisement literacy also strongly mediated persuasion effects. Those students who were previously formally trained in ad literacy classes had higher PK and lower susceptibility to persuasive messages, confirming findings that media literacy training develops concept awareness and affective resistance [4,22,28]. The relationship between NAK and PK was significantly more robust with formally trained students in ad literacy, which indicates that systematized knowledge is associated with more intensive processing and use.

Advance knowledge of neuromarketing also affected various model paths. Consumers who were familiar with some neuromarketing terms or principles were both more attentive to persuasive content, but more skeptical (AS) and more dependent on PK. This dual reaction displays that awareness can at the same time heighten attention to persuasive stimuli but also enhance evaluative criticism, an indicator of a developing persuasion literacy that negotiates engagement with critical distance.

One of the most interesting results was for past ad-clicking history. Students who had never clicked on an ad exhibited stronger NAK on AS and SBA on PI effects, with greater latent resistance or increased sensitivity to persuasion attempts. Students who indicated clicking on ads exhibited weaker engagement of cognitive and attitudinal defenses, indicating that past ad-clicking can make persuasive exposure normal, making reflective processing less likely [4,22,28].

Together, these moderation effects point to the influence of online experience, media education, and age on how adolescents process and react to persuasive messages. They emphasize the need for developmental and experience-informed, age-relevant content and pedagogy media literacy interventions for students’ digital and developmental selves. Any future initiatives need to move away from one-size-fits-all solutions, recognizing that resistance to digital persuasion is dynamically crafted at the knowledge–experience–self-regulation nexus [11,33,34].

6. Practical Implications

6.1. Implications for Educators and Educational Institutions

The study’s results highlight the imperative of integrating disciplined advertising literacy and neuromarketing sensibility education into school courses. The students previously trained in advertising literacy showed much greater persuasion knowledge (PK) and advertising skepticism (AS)—two pivotal cognitive and attitudinal defense strategies in today’s cluttered digital media landscape. Interestingly, subgroup analyses depicted that operations like NEI on PK and SBA on PK were more robust in students with formal ad literacy instruction, affirming that education with focus improves the skill of students to decode advertisements and provide critical comments [11,33,34].

Educational institutions should thus consider integrating advertising literacy, sensitivity to neuromarketing, and the examination of web persuasion into current media studies, civic studies, or ICT courses. The modules must move beyond surface-level explanations of advertising and instead focus on reinforcing students’ skills for strategy detection, like personalization, emotional manipulation, and subliminal stimuli. Educators must create conceptual consciousness (e.g., of neuromarketing instruments) and attitudinal sensitization, e.g., resistance to manipulative strategies and critical thinking.

Above all, however, the process of developing in this study—where younger adolescents (12−13) experienced both persuasion knowledge and resistance, and older adolescents (14−15) were also more behaviorally reactive towards commercials—suggests that there is an early window for intervention [11,33,34]. Ad literacy education at the preadolescent stage could potentially lead to stronger critical habits, whereas interventions in older adolescence must emphasize more behavioral outcomes, moral shopping, and cyber decision-making. Lastly, schools can include project-based and interactive tasks, including ad analysis workshops, digital media diaries, or simulated ad design, to actively involve students in identifying and deconstructing persuasive strategies. Such applied methods can facilitate the transfer of learning to everyday media use [44,46,47].

6.2. Implications for Policymakers

Educational policymakers have a particular responsibility to mainstream and make possible such education interventions that build up digital resilience in young people. Given the empirical findings of this study that formal education enhances cognitive resistance to advertising, national education policies should mandate that it becomes mandatory for primary and secondary school curricula to have age-specific modules on advertising literacy. Such curricula would be taken from effective European media literacy guidelines but framed to take account of the amplified use of AI-based personalization and neuromarketing strategies [44,46,47].

Also highlighting the disparity of susceptibility by access to education are findings indicating that students who had not been exposed to neuromarketing—or who had no prior media literacy training—were more susceptible to ad influences (i.e., inferior PK and more robust SBA on PI trajectories) [11,33,34]. To reduce such disparities, media literacy must be conceptualized as a civic right, not an elective course of study offered in some schools or locations but not others.

Regulatory agencies can also work with ministries of education to certify standards for advertising literacy curricula, benchmarked to psychological and developmental standards [9,43,45]. Meanwhile, consumer protection law needs updating to deal with the insidious psychological influence of algorithmic and neuromarketing methods on children. That this research affirmed that even awareness of neuromarketing can both enhance skepticism and behavioral vulnerability indicates that informed consent, transparency, and ethical boundaries in advertising to children need to be reinforced.

6.3. Implications for Neuromarketing Practitioners and Advertising Designers

For advertisers, marketers, and neuromarketing designers, the research provides useful insights into adolescent consumer psychology. Perhaps most forcefully, Screen-Based Advertising Exposure (SBA) consistently predicted Purchase Intentions (PIs), with effects being stronger in older teens [9,43,45]. Despite such sensitivity to behavior, however, such sensitivity was qualified by prior education, age, and prior exposure to advertising. Such results suggest that content or algorithmic targeting of certain segments can be highly potent, but perhaps have a reversed effect in others, particularly if perceived as intrusive or manipulative. One of the central implications of this is that adolescent audiences are not so much passive receivers—instead, their reactions are subject to cognitive development, education, and past experiences [9,43,45]. Incongruent personalization, particularly among critical or media-conscious youth, can be defensive, draining trust and interest. Thus, ad professionals should not employ aggressively targeted communications, especially among youth audiences, and instead prefer open, instructional, and ethically reasonable messages that are respectful of cognitive autonomy.

In addition, the fact that interest in neuromarketing (NEI) is a predictor for more skepticism in the absence of cognition is a paradox: interest without contextual critical consideration might well be the enemy of it. This highlights the importance of authenticity, explainability, and value-based appeals to campaign design. It will be to the benefit of marketers to incorporate education or awareness-building elements within messaging, particularly when messaging with younger or digitally savvy segments. Lastly, neuromarketing specialists should work with educators and psychologists to create material that is age and cognitively suitable, progressing toward an ethically balanced approach of persuasion. By recognizing the ethical dilemma of engagement and manipulation, entrepreneurs can reconcile business planning and developmental science with social duty.

7. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

This research sheds light on children’s interaction with the digital advertising environment by uncovering that ad literacy, screen-based exposure, and neuromarketing awareness play a crucial role in their cognitive and behavior outcomes [11,33,34]. The results are consistent with a dual-pathway theory of persuasion and resistance, age- and experience-modulated, and highlight the key role of education in enabling young consumers to decode, resist, or comply with persuasive messages. The results have important implications for digital ethics, child protection, and learning innovation in an algorithmic advertising era [11,33,34].

Though its strength, this research has some limitations. As an extension of this research, subsequent studies can continue constructing persuasion literacy with richer, multi-method designs [43,70,71]. For example, longitudinal designs would be particularly appropriate in following how advertisement literacy develops over time, given that students are being exposed to greater levels of algorithmically filtered content. These designs can assist in untangling the temporal relationships of awareness, resistance, and behavior change—a topic that is developmentally ripe for study [43,70,71]. In addition, the inclusion of behavioral tasks or the simultaneous presentation of media in future research would offer findings with more ecological validity. The combination of self-report with observational evidence or experimental manipulation can uncover inconsistencies between what students report and actually do in response to influence attempts in context [9,43,45]. Extending this line of inquiry to modern-day educational and cultural environments is a complementary avenue. Given varying media environments and advertising regulations worldwide, comparative cross-cultural research may challenge the global generalizability of current evidence as much as discover culturally unique patterns of resistance or openness to persuasion. In relation, it would be fascinating to explore how various curricula of digital literacy in various sociocultural environments affect the acquisition of critical advertising skills [6,26,42]. Subsequent research could also consider the influence of emerging forms of persuasory technology—i.e., AI-based personalization, influencer marketing, and gamification advertising—on adolescent decision-making. The novel formats introduce novel challenges and are apt to engage with cognitive defenses such as PK and AS differently. The combination of psychophysiological or neuromarketing methods (e.g., eye-tracking, pupillometry, EEG) may further clarify the insidious, frequently unconscious dynamics within which online persuasion is exerted [6,26,42]. Lastly, there is the possibility to extend the existing model by including psychosocial and motivational variables such as peer influence, emotional control, materialistic orientations, and digital well-being. These variables may interact with persuasion knowledge to strengthen or buffer advertisement impacts, particularly on highly engaging media channels like social media or video-sharing applications [6,26].

Overall, although this research further extends our knowledge about youth reactions to neuromarketing and screen promotion, future studies are desired, utilizing a broader range of methods, populations, and frameworks, which will be useful to inform educational interventions as well as codes of ethics for influence throughout the digital communication age.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B. and C.Z.; methodology, S.B. and C.Z.; software, S.B.; validation, S.B. and K.K.; formal analysis, S.B.; data curation, S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B. and L.L.; writing—review and editing, S.B. and L.L.; visualization, S.B.; supervision, S.B. and C.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC), University of Patras, Greece (protocol code 14045; approval date 26 August 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Measurements used for data analysis.

Table A1.

Measurements used for data analysis.

| Interest and Engagement with Neuromarketing (NEI) | ||