1. Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurodegenerative disease specifically affecting motor neurons with no known cures or effective treatments. The disease is heterogeneous in its pathophysiology, but is uniformly defined by the continual degeneration of upper and lower motor neurons, causing the progressive reduction in muscle function, inevitably culminating in the loss of respiratory muscle function and fatal respiratory failure. Approximately 90% of ALS cases are sporadic (sALS) with no known inherited genetic mutations, and the remaining 10% of familial cases (fALS) are causally linked to genetic mutations, which are usually inherited in an autosomal-dominant manner [

1,

2]. Mutations to the

SOD1 gene encoding Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) account for 20% of fALS cases [

3]. SOD1 is a ubiquitously expressed, primarily cytosolic, oxireductase metalloenzyme that catalyzes the disproportionation of harmful superoxide radicals to mitigate oxidative stress. The native structure of the wild-type (WT) enzyme is a 32 kDa homodimer consisting of two 153 amino acid monomers, each including one catalytic Cu

1+/2+ ion cofactor, one structurally stabilizing Zn

2+ ion cofactor, and one intramonomeric disulfide bond [

4]. WT holo-SOD1 is one of the most stable naturally occurring proteins with a melting point of up to 95 °C and with enzymatic activity conserved even in the presence of strong denaturing agents such as urea or guanidine hydrochloride [

4]. The notable stability of SOD1 is a result of the intramonomeric disulfide bonds and incorporation of the metal ion cofactors, particularly the zinc cofactor, which facilitates a hydrogen bonding network, and, finally, dimerization through hydrophobic intermonomeric contacts. In contrast to dimeric holo-SOD1, monomeric SOD1 lacks most or all of these structure-stabilizing elements, is intrinsically unstable with a greatly reduced melting point (42.9 °C), and has a tendency to adopt non-native conformations and associate with other misfolded SOD1 species [

5].

More than 150 fALS-causative mutations to SOD1 have been identified, the majority of which are amino acid substitutions [

6]. Mutations influence the folding, stability, maturation, and enzymatic function of SOD1 to varying degrees, disparately altering the SOD1 conformational landscape and leading to accumulation of SOD1 aggregates in the spinal cords of patients [

2,

6,

7]. Despite the fact that these mutations all lead to an ALS disease phenotype, albeit to different degrees of severity, fALS mutation sites are scattered throughout the SOD1 sequence, disrupting various aspects of the protein’s structure [

6,

8,

9]. Mutants of SOD1 are categorized into two groups according to the type of structural distortion they exert on the protein. Mutations that produce relatively subtle changes to the protein’s native fold are called wild-type-like (WTL) mutations, while mutations that directly distort the metal-binding region are called metal-binding region (MBR) mutants. The changes to the structure, metal binding, and enzymatic activity observed in WTL and MBR mutants differ significantly, and there is also significant diversity in the biophysical properties of mutants within each category [

4]. Further, the indirect modulation of metal-binding region residues through allosteric pathways impacts the metal-binding affinity of various WTL mutants as well [

4,

10].

The ALS-associated pathogenicity of misfolded SOD1 has been extensively proven to result from a gain of toxic function rather than the loss of enzymatic activity. Many WTL mutants, for example, retain some degree of enzymatic activity, and SOD1 knockout mice do not exhibit ALS-like motor neuron degeneration [

4,

7,

11,

12,

13]. Insoluble aggregates of mutant SOD1 were found to accumulate in fALS motor neurons, and early studies suggested that motor neuron degeneration could be a direct result of large aggregate formation [

11]. Further research, however, has disproven this hypothesis as growing evidence suggests that the toxic species are a variety of soluble oligomers of misfolded SOD1, while disease-correlated aggregates instead serve a protective function by sequestering these toxic species [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Additionally, pathogenic misfolding of WT-SOD1 has been reported in sALS cases by post-mortem analyses [

3,

19,

20,

21]. Soluble oligomeric species of misfolded WT-SOD1 in sALS spinal tissue have been shown to react with antibodies that specifically recognize conformational epitopes present in misfolded species of fALS mutant SOD1 [

3,

19]. These discoveries suggest that pathogenic SOD1 species in familial and sporadic cases can adopt similar aberrant conformations.

Considering that a common ALS phenotype is achieved as a result of dissimilar structural perturbations to SOD1, and that similarly misfolded SOD1 species are present in fALS and sALS patients, the analysis of non-genetic factors, including post-translational modifications (PTMs) that influence SOD1 folding, is vital to sALS research. SOD1 is ubiquitously expressed throughout the body, and it is still not understood why motor neurons are the targeted cell type. We hypothesized that there could be structure-disrupting PTMs to SOD1 that are exclusive to motor neurons and may be the reason for cell-type specificity in ALS. Several asparagine-deamidated variants of SOD1, for example, have been investigated by computational methods and found to have a significant influence on the propensity to misfold and adopt mutant-like ALS-relevant isoforms [

22]. Some of such deamidated forms have been identified with increased frequency in fALS cases [

23].

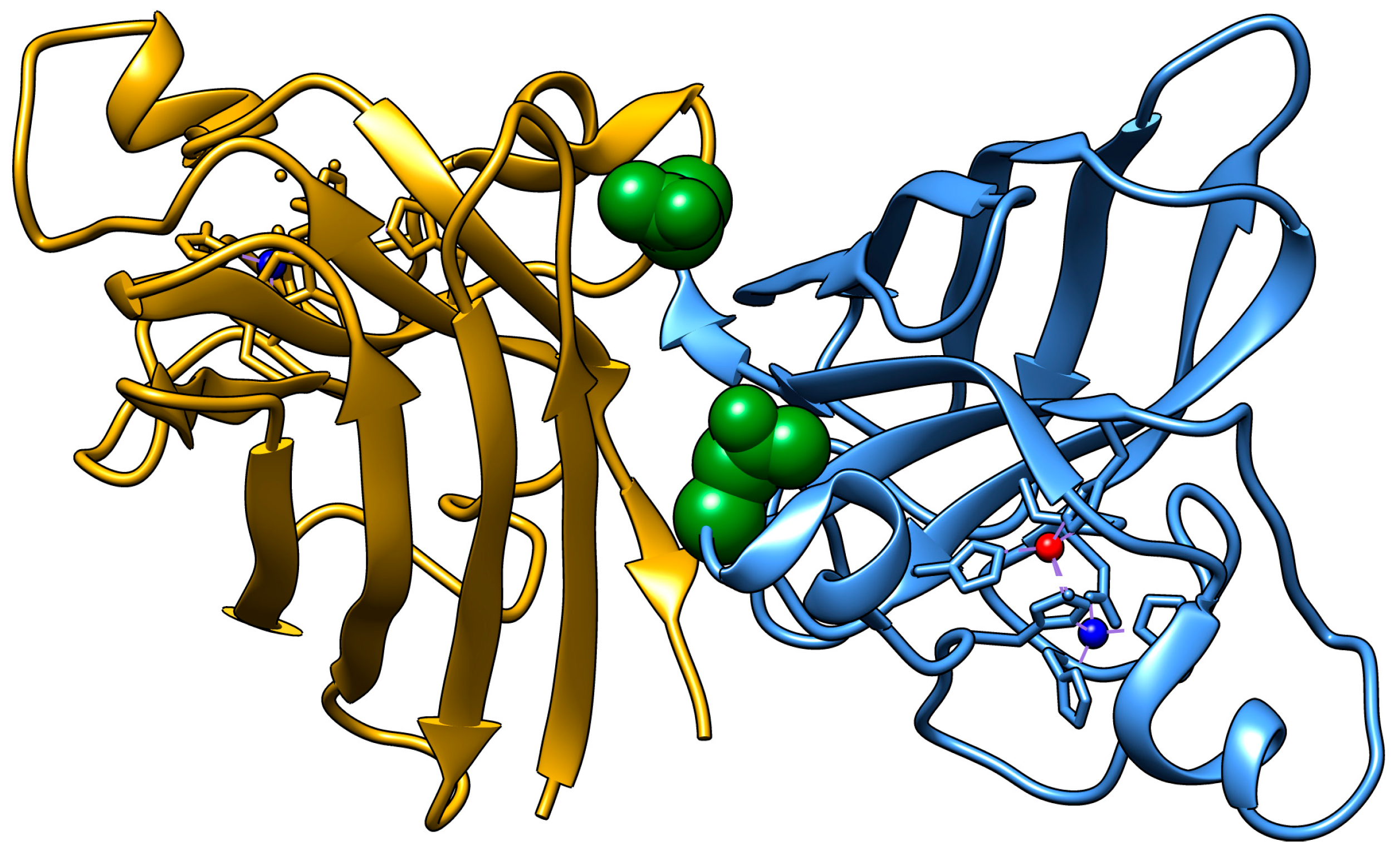

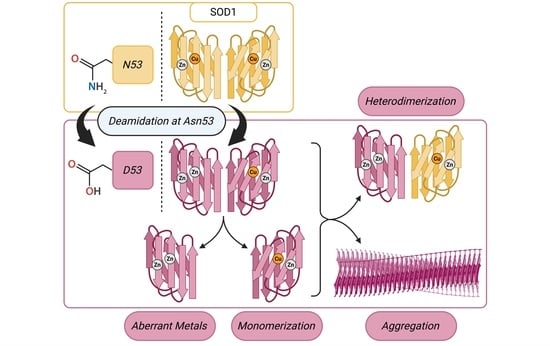

One possible site for asparagine deamidation, Asn53 (N53), was expected to be relatively rare with its deamidation predicted to occur sixth out of the seven Asn residues, but this ostensibly rare PTM was detected with more than 10-fold higher frequency in fALS patient spinal cord tissue compared to healthy controls, making it the Asn deamidation with the second greatest increase compared to healthy control [

22,

23]. The N53 residue is located near the dimer interface within both the Zn binding loop and the GDNT motif of the disulfide loop through Cys57, which is involved in copper chaperone association (

Figure 1). The residue is also located near the Cu binding residues H46 and H48, as well as the Cu/Zn binding residue H63. The deamidation of N53 introduces a non-native negative charge, thereby modifying the electrostatic environment of this region vital for the structural stabilization of SOD1.

Here, we describe the identification of deamidation of SOD1 at N53 in WT human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived motor neurons and characterize how this PTM affects SOD1 structural stability. This deamidation was not detected in SOD1 extracted from non-neuronal cultures differentiated from the same iPSC line, suggesting that the PTM may be specific to or may occur with greater frequency in motor neurons. Using recombinantly expressed N53D SOD1, a SOD1 mutant that mimics N53-deamidated WT SOD1, we measured increased formation of monomer, decreased thermal stability, and increased aggregation propensity when compared to WT SOD1. Investigation of SOD1 metal cofactors showed that N53D SOD1 binds more Zn than WT, exceeding the quantity of Zn binding sites, suggesting longer-range structural perturbations affecting the Cu binding site. Molecular dynamics simulations echo these findings, showing more conformational flexibility in the N53D mutant. Interestingly, modeling predicts the N53D-WT heterodimer to be more stable than the WT-WT homodimer, suggesting another route to toxicity in vivo. Through the identification and characterization of SOD1 PTMs, we gain a better understanding of the in vivo landscape that can lead to SOD1 misfolding and ultimately ALS.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and SOD1 Immunoprecipitation

Our research uses de-identified, established human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) lines. The creators of the lines, Harvard University (Harvard Stem Cell Institute), maintain the signed donor consent forms. All research has a “non-human subject” designation from Wesleyan’s Institutional Review Board and approval from Wesleyan’s Embryonic Stem Cell Research Oversight committee.

iPSCs were differentiated into motor neurons and astrocytes using established protocols with no modifications [

24,

25]. The WT 1016a iPSC and the SOD1 A4V patient-derived iPSC line were obtained from the Harvard Stem Cell Core. iPSCs were maintained on ESC-qualified Matrigel (Corning, Tewksbury, MA, USA)-coated dishes and a mTesr Plus medium (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) before differentiation. Post-differentiation cellular identity was confirmed with immunofluorescent labeling (

Supplemental Figure S1).

To detach adherent cells, the culture medium was aspirated from the plate and immediately replaced with Accutase at an appropriate volume to fully cover the cells. The plate was then incubated at 37 °C for 5 min. Detached cells in Accutase were added to media, gently pipetted to create a single-cell suspension, and centrifuged at 300× g for 5 min to pellet. The cell pellet was washed 2× with sterile PBS to remove media before being stored at −80 °C.

Frozen cell pellets were first lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (RIPA) supplemented with 10 µL/mL Halt protease/phosphatase inhibitor and 2 µL/mL DNAse for 30 min on ice (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Lysates were next subjected to three freeze/thaw cycles before clarification by centrifugation at 16,000× g × 10 min. The supernatant was collected, and total protein concentration was determined via BCA analysis. A SOD1 antibody cocktail consisting of 10 µg each of two antibodies (ProteinTech, Rosemont, IL, USA cat # 10269-1-AP and Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA cat # ADI-SOD-100-J) was added to the normalized lysate, and the mixture was incubated at 4 °C overnight while mixing. The next day, 30 ug of magnetic protein A/G beads (Sera-Mag SpeedBeads™, Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA) were added to the mixture and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Beads were collected with a magnetic stand, and the supernatant was discarded. Washing and binding were performed following the manufacturer’s recommendations.

2.2. Bottom-Up Untargeted Protein Identification and Label-Free Quantification by Tandem Mass Spectrometry

Immunoprecipitated samples of cellular SOD1 were analyzed alongside the commercial SOD1 protein standard for coverage reference and comparison. All samples were reduced with 5 mM fresh DTT for 1.5 h at room temperature, alkylated with 10 mM fresh iodoacetamide for 45 min at room temperature protected from light, and digested with trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI, USA cat # V5113) at a 1:20 enzyme/protein (w/w) ratio overnight at 37 °C. Peptide-containing supernatant was removed from the beads for IP samples. All peptide solutions were acidified and desalted over C18 resin spin columns (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA cat # 89870). Samples were dried to completion, resuspended in a minimal volume of Fisher Optima grade water with 0.1% formic acid, and quantified by absorbance at 280 nm. The injection amount was normalized across all samples.

Samples were analyzed using a Thermo Scientific Ultimate 3000 RSLCnano ultra-high performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) system coupled to a high-resolution Thermo Scientific Q-Exactive HF mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Each sample was injected onto a nanoEase M/Z Peptide BEH C18 column (1.7 μm, 75 μm × 250 mm, Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) and separated by reversed-phase UPLC using a gradient of 4–30% Solvent B (0.1% formic acid in Fisher Optima LC/MS grade acetonitrile) over a 50 min gradient at 300 nL/min flow, followed by a ramp of 30–90% Solvent B over 10 min, for a 60 min total gradient.

Peptides were eluted directly into the Q Exactive HF using positive mode nanoflow electrospray ionization. MS1 scans were acquired at 60,000 resolution, with an AGC target of 1 × 106, maximum ion time of 60 ms, and a scan range of 300–1800 m/z. Data-dependent MS2 scans were acquired at 15,000 resolution, with an AGC target of 1 × 105, maximum ion time of 40 ms, isolation window of 2.0 m/z, loop count of 15, normalized collision energy of 27, dynamic exclusion window of 30 s, and charge exclusion applied for unassigned, +1, and >+8 charged species.

Raw data were searched using MaxQuant v1.6.10.43 and its embedded Andromeda search engine, and quantified using label-free quantification [

26]. Databases included the Homo sapiens reference proteome downloaded from UniProt (UP000005640, downloaded 11 September 2020), the MaxQuant contaminants database, and a custom user-provided SOD1 sequence. Minimum peptide length was set to 7 residues and maximum mass to 4600 Da. Up to 5 variable modifications per peptide were allowed from the following list: oxidation (M), acetylation (protein N-term), acetylation (K), deamidation (N/Q), GlyGly (K), and phosphorylation (S/T/Y). Carbamidomethylation was fixed for cysteine residues. Match between runs was enabled, with a matching time window of 0.7 min. All results were filtered to a 1% false discovery rate at the peptide and protein levels using the target-decoy approach; all other parameters were left as default values. MaxQuant output files were imported into Scaffold 5 (v5.2.0, Proteome Software, Inc., Portland, OR, USA) for data visualization and subsequent analyses.

2.3. Expression and Purification of Recombinant GST-Fusion SOD1

A pCW vector encoding GST-fusion H46R-SOD1, originally provided by Biogen, Inc., was used as the backbone for the construction of GST-fusion WT- and N53D-SOD1 expression plasmids. The pCW plasmid was modified by site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) using 18–22 nucleotide primers to replace a single nucleotide per reaction, introducing a single amino acid substitution. SDM was first performed to generate a GST-WT-SOD1 construct by R46H (CGT to CAT) substitution. After the GST-WT-SOD1 construct was transformed into DH5α cells for cloning, the extracted plasmid was purified and sequenced before further SDM. The N53D (AAT to GAT) substitution was then similarly introduced to the WT construct, cloned, and sequence confirmed. BL21-Codon+

E. coli were transformed with the GST-SOD1 plasmids, and the recombinant protein was expressed in LB media containing 100 µg/mL ampicillin at room temperature with 200 rpm shaking. Protein expression was triggered with the addition of IPTG to a final concentration of 0.2 mM at OD

600 ≈ 0.6. Expression continued for 8–16 h before cells were harvested by 10 min of centrifugation at 5000×

g. Cell pellets were lysed by first performing a freeze–thaw cycle in liquid nitrogen and warm water, then again after resuspension in 3–5 mL lysis buffer per gram (50 mM Tris, 400 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 1% Triton X-100, pH 8.0). Cells were further lysed by sonication on ice at 80% amplitude for 10 cycles of 15 s on, 50 s off. Benzonase nuclease was then added to the lysates at approximately 1 unit per milliliter of lysis buffer before mixing at room temperature for 30–60 min, or until sufficient digestion of DNA was observed. Lysates were then clarified by centrifugation at 10,000×

g for 30 min. After pre-equilibrating with 3× bed volumes of lysis buffer, the supernatants were pumped at 0.5–1 mL/min over a column packed with 15 mL of GST affinity glutathione agarose resin (GoldBio, St. Louis, MO, USA cat # G-250) using an AKTA Explorer FPLC P-960 sample pump (Cytiva, Uppsala, Sweden) at room temperature. The GST affinity resin was then thoroughly washed with 5–10× bed volumes of wash buffer (50 mM Tris, 400 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) at 1–3 mL/min before resin-bound SOD1-GST was eluted with 7–15× bed volumes of elution buffer (50 mM Tris, 400 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM L-Glutathione, pH 8.0). The eluted protein was collected in 10 mL fractions, and SDS-PAGE of each fraction was performed to identify peak fractions of SOD1-GST fusion protein and assess the purity of the protein samples (

Supplemental Figure S2). The GST affinity resin was regenerated according to the manufacturer’s specifications after each use.

2.4. Processing and Maturation of Recombinant SOD1-GST

Peak fractions of SOD1-GST fusion protein were pooled, and 10 mM DTT was added to the solution to reduce disulfide bonds to glutathione. The reduced protein was then subjected to dialysis against 4 L of wash buffer at 4 °C in 6–8 kDa MWCO tubing (Spectra/Por

®, Waltham, MA, USA) to remove reduced glutathione from solution. The dialysis membrane was then buried in powdered PEG 20,000 at 4 °C to concentrate the solution by dehydration, and concentrated samples were then subjected to another round of dialysis against GST wash buffer in a fresh dialysis membrane. During this dialysis, the GST tag was cleaved from SOD1 by the addition of HRV-2C Protease according to the manufacturer’s specifications (ACRO Biosystems, Newark, DE, USA cat # 3CC-N3136). Once total tag cleavage was confirmed by SDS-PAGE after 16–24 h, the solution was pumped through the regenerated GST affinity resin column to remove the cleaved GST tag and GST-tagged protease. After GST removal was confirmed by SDS-PAGE, the SOD1 solution was subjected to a series of dialysis steps to mature the apoprotein (

Supplemental Figure S2). The tag cleavage results in a “tag scar”, which leaves behind an additional 8 amino acids on the N-terminus (GPLGSPEF). This tag scar is consistent between WT and N53D.

Next, protein was dialyzed against an EDTA-rich buffer (50 mM Tris, 200 mM NaCl, 100 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) to remove any contaminating non-native divalent metal ions. Second, the solution was dialyzed against an acidic buffer solution to encourage unfolding of apo-SOD1 (100 mM sodium acetate and 200 mM NaCl, pH 3.8). Third, the solution was dialyzed against a refolding buffer (25 mM MOPS and 200 mM NaCl, pH 6.9) into which metal cofactor addition, described in the following section, could be performed while maintaining near-neutral pH with minimal precipitate formation. After the addition of metal cofactors, the solution was dialyzed against the Tris buffer (25 mM Tris, 200 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) to remove unreacted metals, and then finally against PBS (11.8 mM PO4, 137 mM NaCl, 4.5 mM KCl, pH 7.4) before dimeric Cu/Zn SOD1 was purified by size exclusion chromatography.

2.5. Metal Addition to Apo-SOD1

In vivo, passive zinc cofactor uptake precedes chaperone-catalyzed copper insertion into SOD1. Maturation of recombinant SOD1 to generate holoprotein in vitro is proceeded by the direct addition of metal cofactors in the same order without a copper chaperone; Zn2+ solution (1 M ZnCl2) was added directly to the apo-SOD1 MOPS solution to a final concentration of 10 mM Zn2+ and incubated at 4 °C overnight with stirring, and then Cu2+ solution (0.5 M CuCl2, 1.5 M Tris, pH 8.0) was added to a final concentration of 10 mM Cu2+ before further incubation at 4 °C overnight with stirring. In comparing WT to N53D, obstruction to the metal binding region was expected. To probe the influence of N53 deamidation on the metal binding region, apoprotein pools were split before maturation, with some being treated first with zinc as described and some being treated first with copper instead. These variants are hereafter referred to as WT/N53D SOD1 Zn-first or Cu-first, or alternately as WT/N53D Zn or WT/N53D Cu, respectively.

2.6. Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC)

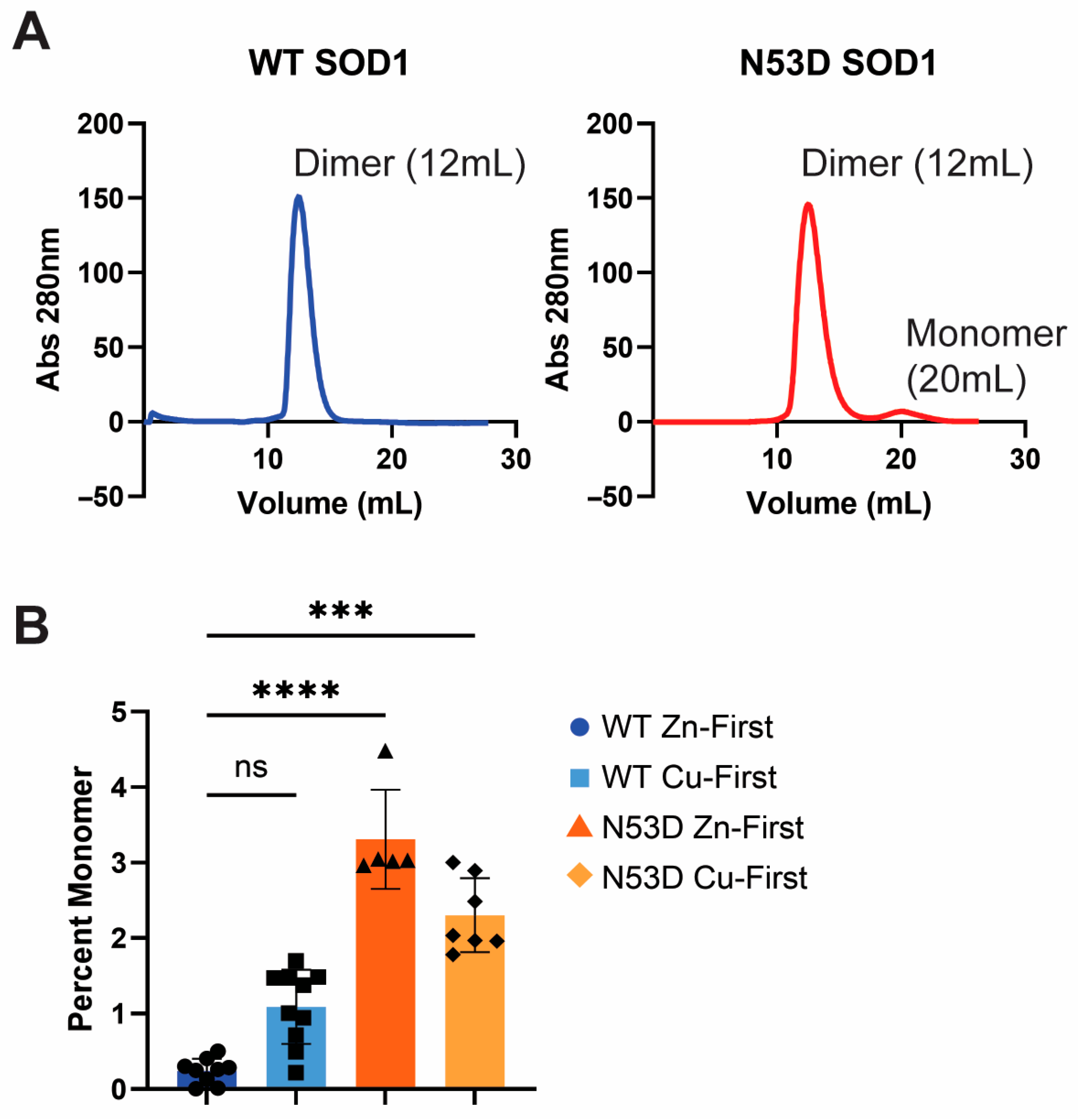

Dimeric SOD1 was purified by SEC using an AKTA Explorer FPLC system (Cytiva, Uppsala, Sweden). Protein samples were first centrifuged at 10,000× g for 5 min before being loaded into the system in 1–2 mL injections. The protein was run over a Superdex™ 75 Increase 10/300 GL column (Cytiva, Uppsala, Sweden) at a flow rate of 0.75 mL/min at room temperature, and 1 mL fractions were collected. Dimer fractions for each biological replicate of each Cu/Zn addition order variant were separately pooled, and each dimer pool was then concentrated to approximately 30 µM using 10 kDa spin columns (Vivaspin®20, Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA). Spin column membranes were first treated with sterile-filtered 20% glycerol to minimize protein binding. Peak integration tools in Unicorn 5.31 software were used to integrate the dimer (12 mL) and monomer peaks (20 mL), to calculate a ratio of monomeric to dimeric SOD1. The relative quantities of dimer and monomer were also used to estimate the ∆∆G of dimerization for each variant using the following equation: , where for the holoprotein standard (KWTZn) and the SOD1 variant (Kx). Absorbance at 280 nm SEC chromatograms from at least 3 independent growths of WT and N53D SOD1 were used to calculate the monomer/dimer ratios.

SEC-purified SOD1 was subjected to intact mass spectrometry to confirm sequence identity. Mass spectrometry also confirmed that the intramonomeric disulfide was present in both species (−2 Da from expected mass, cysteine disulfide bond between AA65-AA154, corresponding to C57 and C146 in the native sequence shifted by the 8 amino acid tag scar) (

Supplemental Figure S3).

2.7. Intact Protein Analysis by Tandem Mass Spectrometry

Purified recombinant WT and N53D SOD1 was quantified by spectrophotometer absorbance at 280 nm. The sample was diluted to 10 pmol/μL in Solvent A (0.1% formic acid in Fisher Optima grade water) and analyzed using a Thermo Scientific Ultimate 3000 RSLCnano ultra-high performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) system coupled with a high-resolution Thermo Scientific Eclipse Tribrid Orbitrap mass spectrometer.

Chromatography was performed using a nanoEase M/Z Protein BEH C4 column (1.7 μm, 75 μm × 100 mm, Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) heated to 50 °C with a reversed-phase UPLC gradient of 4–30% Solvent B (0.1% formic acid in Fisher Optima LC/MS grade acetonitrile) over a 50 min gradient at 300 nL/min flow, followed by a ramp of 30–90% Solvent B over 10 min, for a 60 min total gradient. Proteins were eluted directly into the Eclipse using positive mode nanoflow electrospray ionization with a capillary voltage of 2200 V. MS1 scans were acquired at 120,000 resolution, with an AGC target of 4 × 10

5, maximum ion time set to Auto, RF lens setting of 30%, and a scan range of 300–2000

m/

z. Data-dependent MS2 scans were acquired in the Orbitrap at a resolution of 60,000, for any ions over 2.5 × 10

4 intensity threshold, with AGC target set to 8 × 10

5, maximum ion time set to Auto, mass range set to Normal, scan range set to Auto, isolation window set to 2

m/

z, and a fixed cycle time of 3 s. ETD fragmentation was applied with a 20 ms reaction time, ETD reagent target of 3 × 10

5, and 12% supplemental activation energy applied. Dynamic exclusion was set to exclude for 15 s after 1 observation, for charge states of 8–40. Peak deconvolution was performed in UniDec [

27], with the following parameters: a charge range of 9–20, mass range of 2000–50,000, mass sampled every 1 Da, 5 Da peak detection range, and 0.1 peak detection threshold.

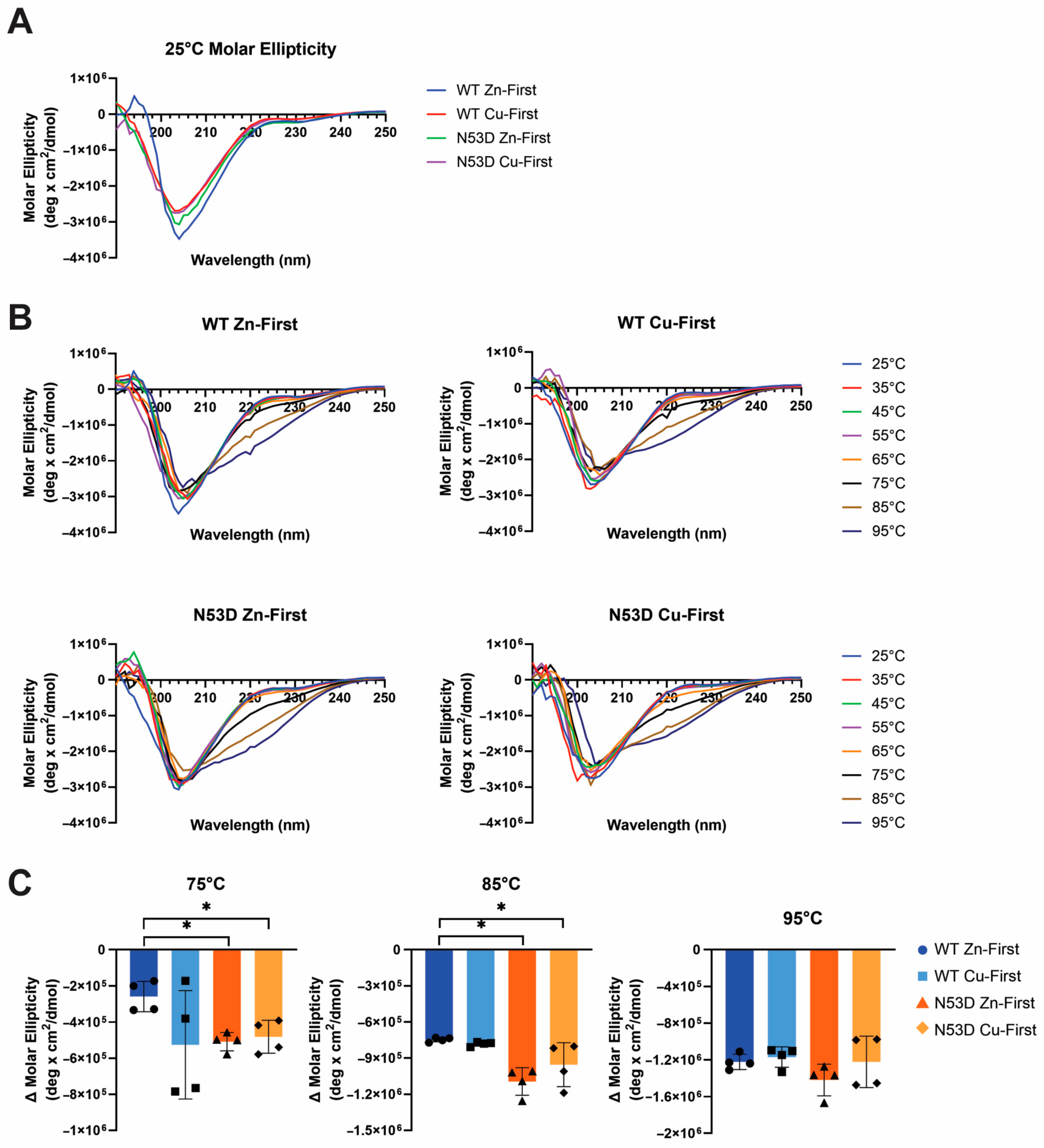

2.8. Circular Dichroism (CD)

Circular dichroism experiments were performed on a Jasco J-810 polarimeter to measure and monitor changes to the secondary structure of SOD1 variants in response to heating. Samples were diluted in PBS to ~14 µM and subjected to a thermal melt from 5 to 95 °C. CD experiments were carried out on 2 independent growths of WT and N53D SOD1 (2 biological replicates) in duplicate (2 experimental replicates). The exact concentration of each sample from A280 nm was used to convert the CD spectra to molar ellipticity, and the resulting 4 CD runs for each species were averaged to create the spectra shown.

2.9. Heated Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

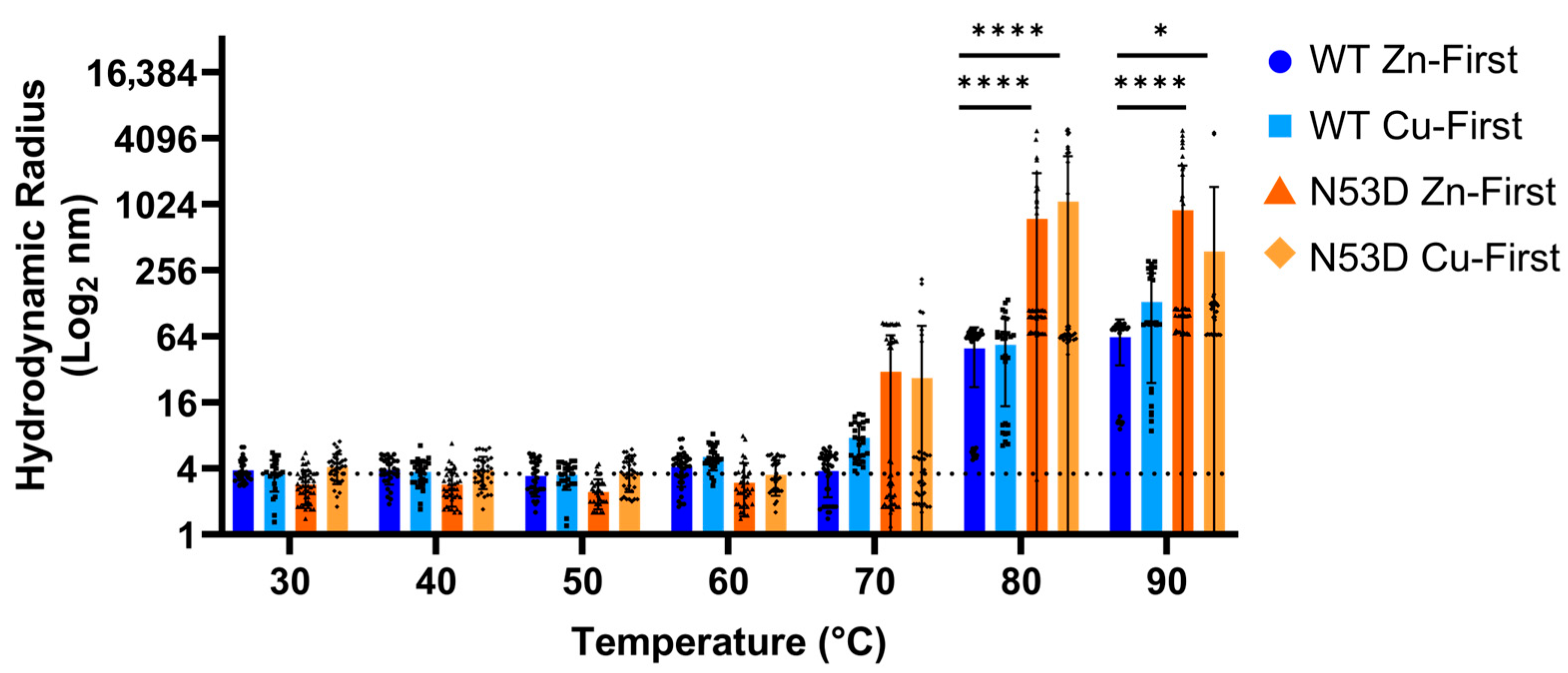

As a complementary approach to determine differences in structural integrity and aggregation propensity, the hydrodynamic radius of purified SOD1 was measured by dynamic light scattering using a Horiba nanoPartica SZ-100V2 Series particle analyzer (Horiba, Tokyo, Japan). After centrifugation at 10,000× g for 5 min followed by filtration through 0.45 micron syringe-tip filters, samples of ~30 µM SOD1 were measured at a 90° angle at temperatures spanning 30 °C to 90 °C in 10 °C intervals, and the Z-average hydrodynamic radius of particles in solution was averaged across viable scans. Samples were held at each temperature for 10 min before each set of DLS measurements, with each measurement consisting of 10 separate scans collected over a 90 s period.

Each 10-scan data set was recalculated using a channel range determined to be most suitable for the specific autocorrelation data. Channel ranges were determined to be suitable first by ensuring the autocorrelation decay was sufficiently captured within the range (i.e., the decay curve occurred before the final point of the channel range) and, where these criteria applied to multiple tested channel ranges, the calculation that yielded the lesser standard deviation of Z-average radii was selected. Prior to finally determining the appropriate channel range, outlier scans were identified by several approaches in the following order: first, scans that yielded non-viable autocorrelation data, such as those showing immediate decay after a single point, were eliminated from the sets. Next, scans yielding a Z-average radius beyond two standard deviations from the average of the set were eliminated. Finally, data with a polydispersity index beyond 10 were eliminated from the set. After the identification and elimination of scan outliers, 3 to 5 experimental replicates of each variant were analyzed, each including the protein prepared from 2 to 3 independent growths.

2.10. Cu2+/Zn2+ Quantification

To determine the abundance of metal cofactors present in the SOD1 variants, divalent copper and zinc ion concentrations were simultaneously quantified with a colorimetric 4-(2-pyridylazo) resorcinol (PAR) chelate complex assay [

28]. The solutions described below were prepared in MilliQ water that was first treated with Chelex

®100 resin to remove any contaminating divalent metal ions. A stock solution of 10 mM PAR was prepared by dissolving PAR in MilliQ water with a small quantity of 1 M NaOH to facilitate total dissolution. The 4X PAR assay working solution (400 µM PAR, 200 mM HEPES, pH 8.0) was then prepared by mixing 1.6 mL of 10 mM PAR with 35 mL of HEPES buffer, adjusting pH with 1 M NaOH and/or HCl, and then diluting to a final volume of 40 mL. All PAR solutions were protected from light by wrapping tubes and plates in aluminum foil and were stored at 4 °C. Solutions of 1 M ZnCl

2 and CuCl

2 were prepared by dissolving the appropriate amount of each solid in MilliQ water, and 250 µM working solutions of each were then prepared by sequential dilutions. A solution of 8 M guanidine HCl (GuHCl) was prepared in warm MilliQ water and also subjected to CHELEX resin to remove metal contaminants.

In a clear 96-well plate (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg, PA, USA cat # 12565501), duplicate or triplicate samples of each SOD1 variant were first denatured in 7 M GuHCl to release bound metal cofactors into solution; 25 µL of approximately 30 µM SOD1 was thoroughly mixed with 168.75 µL of deionized 8 M GuHCl. After incubating for 1 h at room temperature, 56.25 µL of 4× PAR working solution was added to each well for a final assay volume of 250 µL and final sample concentration of 0.1×. Standard curves for Cu2+ and Zn2+ were established spanning a range of either 0–17.5 or 0–10 µM by diluting the appropriate volume of the 250 µM metal standards into PBS for a sample volume of 25 µL with a concentration of 10× the target standard concentration. For standards, a 1× PAR solution was prepared as a 3:1 mixture of GuHCl and 4× PAR. After the addition of 225 µL of 1X PAR to each standard well (i.e., 168.75 µL of 8 M GuHCl and 56.25 µL of 4× PAR per well), all wells consisted of 0.1X initial concentration of samples or standards, 5.4 M GuHCl, 90 µM PAR, and 45 mM HEPES.

Absorbance spectra spanning 300–600 nm were then measured in 5 nm increments using a VarioSkan Lux™ microplate reader (Thermo Scientific) and SkanIt software (v7.0.2) (

Supplemental Figure S4). Spectra for standards and protein samples were then processed in R to establish a standard series for PAR:Cu

2+ and PAR

2:Zn

2+ complexes. With these standards, spectral decomposition of the multicomponent solutions of PAR and unfolded SOD1 was performed by linear least squares fit analysis to quantify the weights of the constituent spectra of PAR, PAR:Cu

2+, and PAR

2:Zn

2+ complexes. The resulting metal concentrations contributing to the composite PAR/SOD1 spectra were then divided by the concentration of SOD1 monomers to determine the relative quantities of each cofactor per binding site in each variant. The PAR assay was performed for each of 3 independent growths of each SOD1 variant.

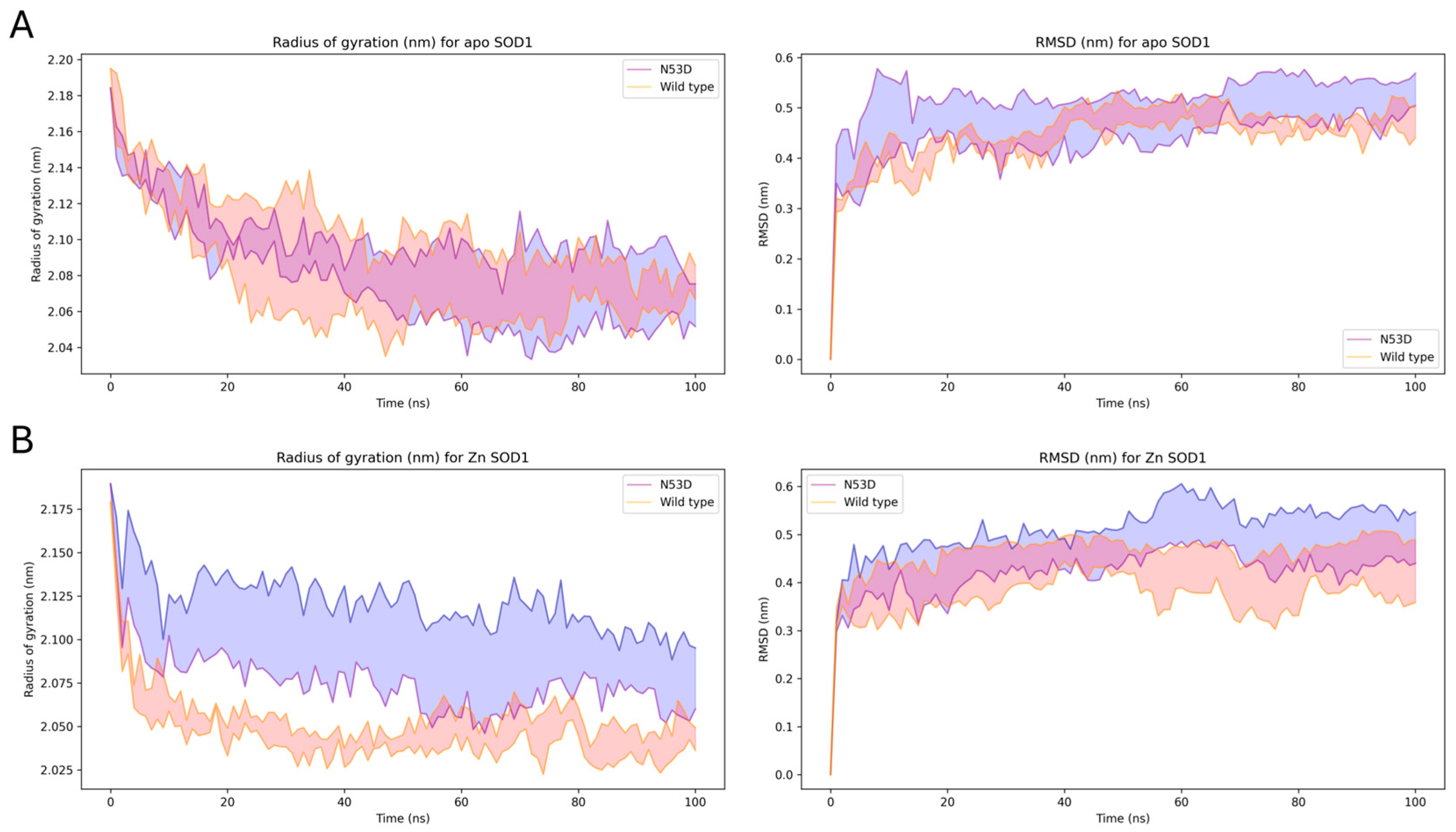

2.11. In Silico Preparation

The reference PDB structure 1HL5 was used, and a GST-tag scar was added using cyclic coordinate descent loop modeling in the Rosetta macromolecular modeling software, such that the resulting primary structure matched that of the recombinant SOD1 used in this study [

29]. Cu

2+ was selectively removed from all variants to match the measured over incorporation of Zn

2+. The mutation at N53 and Cu

2+ removals were performed using PyMOL (v 3.1.6.1). Metal-coordinating histidine residues and an aspartic acid residue were modified based on previous literature [

30].

2.12. Molecular Dynamics (MD) and Alchemical Morphing

Energy minimization was carried out using GROMACS (v2021). Energy-minimized structures were then equilibrated at constant volume and temperature for 200 ps. Following that, structures were equilibrated in three 20 ps NPT simulations using all-atom position restraints of 500 kJ, 250 kJ, and 125 kJ. NPT equilibration was then carried out for another 20 ps, first with backbone restraints only, then with C-alpha restraints only. MD simulations were carried out with GROMACS. The AMBER

ff99SB*-ILDN [

31,

32] force field and TIP3P water model were used. A triclinic box was used with 1.5 nm spacing between the box and the solute. Joung Zn

+ and Cl

− ions were added to the box at a concentration of 150 mM [

33]. Production simulations were run at constant temperature and pressure, with the V-rescale thermostat and the C-rescale barostat holding temperature and pressure constant, respectively. All bonds were constrained using the LINCS algorithm. Free-energy perturbation was performed using the PMX software package and in-house scripts [

34,

35,

36].

4. Discussion

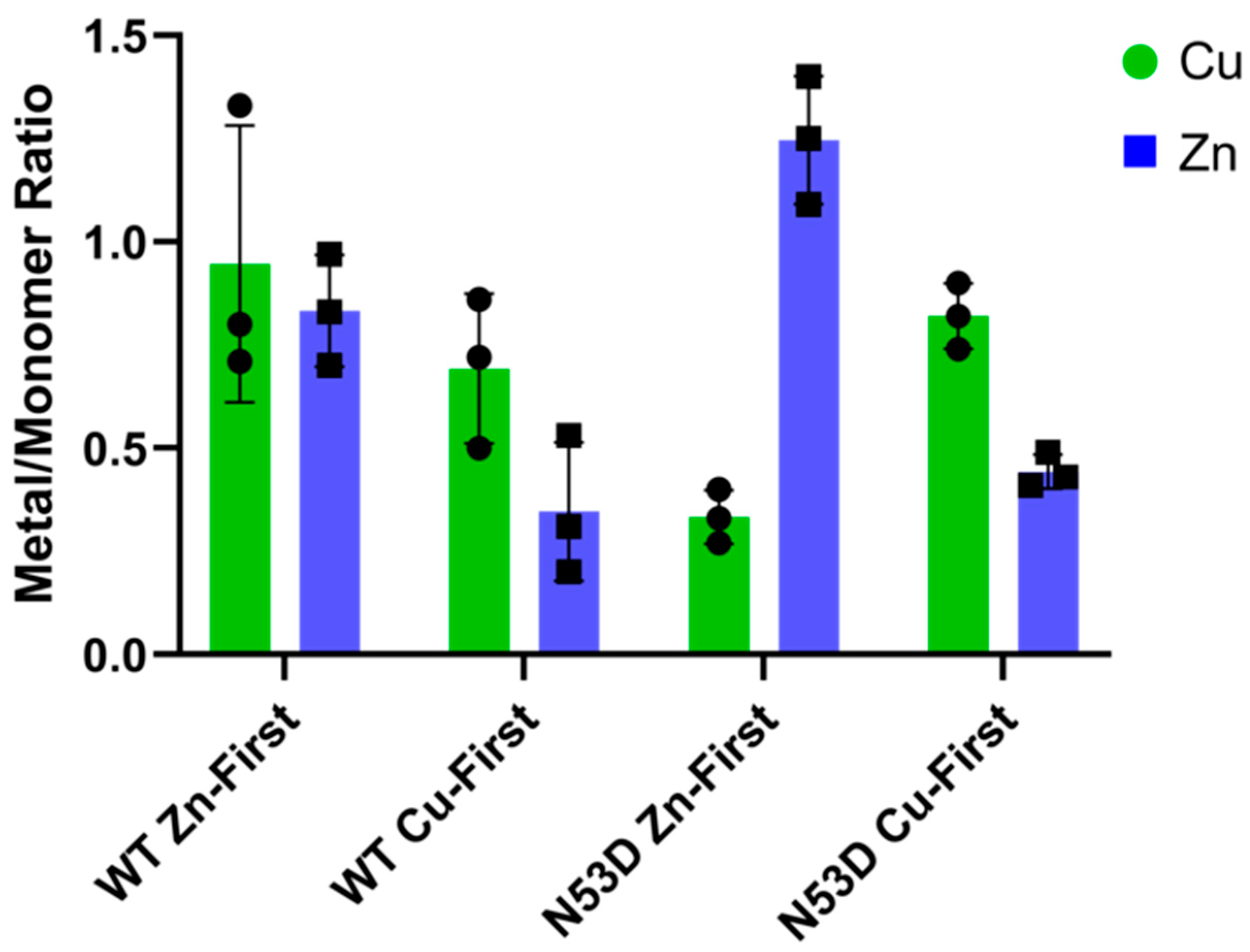

As expected, the holoprotein control, WT SOD1 Zn-first, had the lowest relative abundance of monomers among all variants and a metal cofactor incorporation most in line with that of the native holo-SOD1 dimer. After initial experiments with N53D SOD1 showed an increased abundance of Zn and decreased abundance of Cu when using the in vivo metal addition order (Zn-first), we were interested in further testing metal binding preferences or promiscuity by introducing the metal cofactors in the opposite order as well. This would theoretically help identify if the aberrant incorporation of metals was the result of general promiscuity towards metal cofactors introduced by N53D (i.e., Cu-first addition similarly causes increased Cu and decreased Zn quantities) or if instead N53D introduced a specific change in affinities, namely an increased affinity for Zn and/or decreased affinity for Cu (i.e., Cu-first addition does not cause increased Cu and decreased Zn concentrations). In the non-physiological case of Cu-first metal cofactor addition, a similar non-native metal cofactor abundance was observed in both WT and N53D SOD1 samples, with a similar relative deficiency of Zn2+ cofactors. Both zinc-deficient Cu-first variants had a decreased preference for dimerization compared to the Zn-first WT control; the monomer/dimer ratio of WT SOD1 Cu-first was ~5.5 times that of WT SOD1 Zn-first, while N53D SOD1 Cu-first was ~9.85 times that of Zn-first and ~1.79 times that of WT SOD1 Cu-first. In the case of N53D SOD1 Zn-first, a unique profile of aberrantly high Zn2+ and low Cu2+ incorporation was observed, and this distinct metal cofactor profile corresponded with a distinct decrease in dimer preference with a monomer/dimer ratio ~18.3 times that of the control. Alchemical morphing simulations indicated that the N53D-WT heterodimer is more stable than the WT-WT homodimer, suggesting that our measured increase in N53D monomer could lead to increased heterodimer formation in vivo and increased disease severity.

In these experiments, zinc addition preceding copper addition consistently yielded a greater abundance of coordinated Zn2+ in N53D versus WT SOD1, with the molar quantity of Zn2+ exceeding the predicted molar quantity of zinc binding sites. Additionally, copper addition preceding zinc addition yielded a similarly reduced relative abundance of coordinated Zn2+ in both N53D and WT SOD1. Considered together, these data indicate that metal binding is altered in N53 deamidated SOD1, possibly via an increased affinity for non-native Zn2+ ion coordination to the copper binding site, precluding Cu2+ incorporation. Alternatively, in vivo, mature holo-SOD1 may become deamidated at N53 and lose affinity for Cu and bind another Zn co-factor, as no chaperone is needed for Zn insertion.

Taken together, the data from SEC and PAR experiments indicate that N53 deamidation both generally decreases dimer stability and facilitates a non-native coordination of additional zinc cofactors, further reducing dimer stability. Corroborating this, our room-temperature CD spectra show decreased alpha helicity and beta sheet signatures for variants with non-native metal coordination, namely WT Cu-first and both N53D Cu-first and Zn-first, indicating the importance of native metal incorporation for folding. Importantly, the in vitro model for N53 deamidation in this study was limited in that the N53D mutation mimicking the PTM of interest was present before metal cofactor addition. In contrast, N53 deamidation in vivo is predicted to occur very slowly, most likely after native cofactor incorporation is complete [

22]. However, CD results showing a significant reduction in the ellipticity at 220 nm in N53D variants versus control align with the spectra of metal-free SOD1 in previous studies, suggesting a greater tendency for the mutant to release metal cofactors [

9]. In the case that SOD1 in vivo more readily releases metal cofactors and achieves metal pocket vacancies following N53 deamidation, especially if stabilizing dimerization is reduced as it is in vitro, then the passive uptake of zinc into N53 deamidated SOD1 species could culminate in the observed aberrant metal coordination despite the PTM occurring after the proper maturation of WT SOD1. Previous studies have indeed suggested that aberrant Zn/Zn-coordinated SOD1 species have an increased propensity to misfold, and considering that N53 deamidation was identified specifically in cultured motor neurons, the observation that this PTM may introduce a bias towards Zn/Zn coordination could be relevant to ALS pathophysiology [

39].

Increased misfolding due to N53 deamidation was also captured in heated DLS experiments. Although differences between the control Zn-first WT SOD1 and N53D variants lacked statistical significance at 70 °C, it was notable that an increase in particle size was reflected in the higher cumulative average radius and broader standard deviation in N53D variants. This indicator of aggregation at 70 °C was exclusively observed in N53D variants, more frequently so in Zn-first N53D SOD1. Further, at 80 °C and 90 °C, both metal variants of N53D SOD1 were found to have significantly greater radii than the Zn-first WT control, which had the lowest cumulative average radius of all variants, as expected. The formation of heat-induced aggregates in N53D variants at lower temperatures than Zn-first WT control and the significantly greater size of aggregates at 80 °C and 90 °C indicate that N53 deamidation increases SOD1 aggregability, possibly introducing or enhancing aggregation pathways that facilitate the generation of significantly larger aggregates.

Unstructured monomers readily serve as a feedstock for aggregate growth, and their greater relative population suggests dimer destabilization, which may also facilitate the templated misfolding of dimeric N53D SOD1. Correlations between heated DLS results and relative monomer populations in SEC were apparent; the variant with the least monomer population, Zn-first WT SOD1, achieved the lowest maximum hydrodynamic radius with heating and had no notable propensity to aggregate at 70 °C, while the variant with the highest monomer population, Zn-first N53D SOD1, achieved the highest hydrodynamic radius with heating and showed a propensity to aggregate at 70 °C. This suggests that aberrant Zn/Zn coordination and dimer destabilization facilitate aggregation in N53D SOD1.

Our secondary structure analysis via CD spectroscopy confirms that N53D SOD1 is less stable at higher temperatures (75–85 °C). Notably, at 95 °C, none of the proteins are fully denatured; consistent with the formation of stable aggregates rather than fully melted protein. While stability and metal content analysis would predict gross structural changes, the CD spectra of Zn-first WT and the N53D variants were similar at 25 °C and for much of the melting process. Other studies have corroborated that while Zn/Zn coordinated SOD1 has greater aggregation propensity, the crystal structure of Zn/Zn SOD1 was previously determined to align with that of the native Cu/Zn protein outside of the Cu site [

39,

40].

5. Conclusions

Through mass spectrometry analysis across multiple cell types, we have identified deamidation sites that may be cell-type specific, which may contribute to SOD1 destabilization and, consequently, ALS pathology. Future experiments that would provide further validation of disease relevance and cell-type specificity would include additional IP/MS experimental replicates from tested lines to bolster statistical power, the evaluation of more iPSC-derived cell lines, and ultimately similar evaluations of human tissue. From the preliminary data, the most compelling PTM site for investigation was deamidation at N53 due to the apparent disease cell-type specificity of the PTM and its >10-fold higher frequency in fALS patient spinal cord tissue compared to healthy controls in previous research, as well as because N53 is proximal to critical stabilizing motifs (i.e., the dimer interface, metal binding loop, and disulfide loop), giving modifications at this site notable potential to disrupt SOD1 structure [

23]. As we hypothesized, N53 deamidation reduces structural stability and increases relative monomer populations. Unexpectedly, N53D SOD1 showed an increased affinity for Zn beyond the molar abundance of Zn binding sites, alongside decreased Cu incorporation, suggesting a structural shift allowing the Cu binding site to instead bind Zn. This tendency for N53 deamidated SOD1 to aberrantly bind additional Zn

2+ could be expected in vivo after the release of metal cofactors following N53 deamidation, and the associated non-native SOD1 species could be of interest in the study of sALS pathophysiology. Previous studies have suggested that aberrant Zn/Zn-coordinated SOD1 species have an increased propensity to misfold, and this tendency was observed in the case of the aberrantly Zn overpopulated N53D SOD1 Zn-first variant [

39]. Furthermore, previous studies suggest increased misfolding and toxicity in heterodimeric SOD1 species, the formation of which is both predicted to be favorable in simulations of N53D SOD1 and expected to be enhanced by increased monomer populations, as was observed in SEC of N53D SOD1 [

38]. The influence of this PTM on the properties of fALS mutant SOD1 has yet to be similarly studied, and determining whether N53 deamidation may exacerbate the instability, aggregability, and toxicity of such mutants may also be of interest in future studies.