1. Introduction

Bisphosphonates are synthetic analogs of pyrophosphate that have been used in medical practice since the 1960s, initially for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Nowadays, they remain widely used for managing Paget’s disease, metastatic bone lesions, multiple myeloma, and malignant hypercalcemia [

1]. Structurally, bisphosphonates are characterized by P–C–P backbones with variable side chains (R1, R2), which determine their potency [

2,

3]. They are generally classified into amino bisphosphonates, which are more potent and more often associated with side effects, and non-amino bisphosphonates [

3,

4]. Their mechanism of action involves inhibiting osteoclastic activity, inducing osteoclast apoptosis, and reducing bone resorption while preserving osteoblast activity [

2,

4].

A recent systematic review study from Slovakia indicates specific alterations in proteins, genes, and microRNAs and thus unravels novel insights into the molecular mechanism behind the MRONJ disease [

5].

Pharmacokinetically, they are characterized by low oral bioavailability (~1%) under fasting conditions but prolonged bone retention, which can persist for more than a decade, necessitating strict administration instructions to maximize efficacy and reduce gastrointestinal side effects [

3,

6]. Absorption of bisphosphonates is significantly reduced if taken with food, calcium, iron, or other divalent cations—hence, they should be taken on an empty stomach with water. Patients are advised to remain upright for at least 30–60 min to minimize esophageal irritation and optimize absorption. After absorption, about 50% of the absorbed dose binds rapidly to hydroxyapatite in bone; the remainder remains in plasma or is excreted unchanged by the kidneys. They minimally bind to plasma proteins, and once in bone, bisphosphonates can stay for months to years, slowly releasing as bone remodels. As for the elimination of the bisphosphonates, the fraction not taken up by bone is cleared unchanged by the kidneys. Plasma half-life is short (hours), but the functional half-life in bone is extremely long due to incorporation into bone tissue, so impaired renal function can reduce clearance and increase plasma exposure [

7,

8,

9].

Although generally considered safe, bisphosphonates have been associated with several adverse effects, including gastrointestinal upset, acute post-infusion reactions, nephrotoxicity, and hypocalcemia. Most notable, though, is the bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ) [

2,

3]. First described in 2003, BRONJ is defined as exposed bone in the maxillofacial region that persists for more than 8 weeks in patients receiving treated bisphosphonate therapy without a history of jaw radiation [

10]. As of recently, the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS) classified BRONJ as under the broader term of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) to reflect its association with other antiresorptive and antiangiogenic drugs as well [

11].

BRONJ occurs more frequently in the mandible (68%) than in the maxilla (28%) [

12]. Major risk factors include intravenous drug administration, zoledronate in particular, as well as prolonged therapy, use of high doses of drugs, invasive dental procedures, rheumatoid arthritis, and poor oral health [

4,

6,

12]. Pathogenesis likely involves impaired bone remodeling, inhibition of angiogenesis, and infection, especially those caused by Actinomyces spp., suggesting a possible association with periodontitis. The ability to overcome infection may be inhibited due to the negative effect of bisphosphonates on immune response cells, such as macrophages and T lymphocytes. Decreased pH associated with inflammation may contribute to increased release of bisphosphonates from bone, which promotes destruction of surrounding soft tissue and exposure of necrotic bone, increasing the chance of infection. Other hypotheses include disruption of bone remodeling as the main effect of anti-resorptive drugs, leading to reduced bone remodeling and inhibition of angiogenesis, which prevents the formation of new blood vessels in bone [

2,

12].

According to the AAOMS classification, BRONJ is divided into stages 0–3, based on clinical presentation and radiological findings [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Stage 0 with no clinical evidence of necrotic bone but nonspecific findings—jaw pain, sinus discomfort, or radiographic changes, stage 1 with exposed/necrotic bone or fistula probing to bone without pain or infection. Radiographic changes may be present, stage 2 with exposed/necrotic bone with pain and/or infection (erythema, purulence), and stage 3 with exposed/necrotic bone with pain, infection, and complications, such as pathologic fracture, extraoral fistula, oroantral/oronasal communication, osteolysis extending to the inferior border or sinus floor.

Bisphosphonates strongly bind to hydroxyapatite and inhibit farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase in osteoclasts, reducing bone resorption and remodeling. This impairs regular repair after microtrauma in the jaw. Long-term suppression of bone turnover leads to the accumulation of microdamage and decreased mechanical strength in jaw bones. Some bisphosphonates (e.g., zoledronic acid) inhibit angiogenesis, reducing blood supply and delaying healing. Bisphosphonates may be directly cytotoxic to oral epithelial cells and fibroblasts, impairing mucosal healing, and oral bacteria can colonize exposed bone; biofilms exacerbate inflammation and necrosis. Trauma (e.g., dental extraction) may trigger infection in a compromised environment. The jaw experiences frequent microtrauma, has high bone turnover, and is exposed to the oral microbiome, making it particularly vulnerable compared to other bones [

11,

16,

17,

18].

Prevention of BRONJ is focused on comprehensive dental examination and rehabilitation before bisphosphonate therapy, avoiding invasive procedures during treatment, and taking an individualized approach in close collaboration with a dental specialist or maxillofacial surgeon [

4,

12,

15]. According to the conclusion of a European multicenter study, surgery plays an important role for the management of MRONJ [

19].

Dentists play a central role in the prevention and management of BRONJ. They should obtain and regularly update a complete medical history, including diagnoses, medications, and dosage, while using each visit as an opportunity to educate patients about BRONJ risk, the importance of oral hygiene, and the consequences of neglecting preventive care. A comprehensive dental examination with periodontal assessment and radiographs should be completed at baseline for future comparison. Ongoing care requires dentists to stay informed on current best practices and to work collaboratively with physicians and patients to deliver individualized preventive and maintenance strategies. AAOMS has issued specific guidance to assist dentists in managing patients who are on antiresorptive medications [

11].

Despite a growing body of research evidence, the exact mechanisms of BRONJ formation remain unclear, emphasizing the need for further studies focused on pathophysiology, prevention, and the improvement of therapeutic guidelines [

10,

14].

The aim of this study is to assess dentists’ knowledge about bisphosphonates and their oral side effects.

3. Results

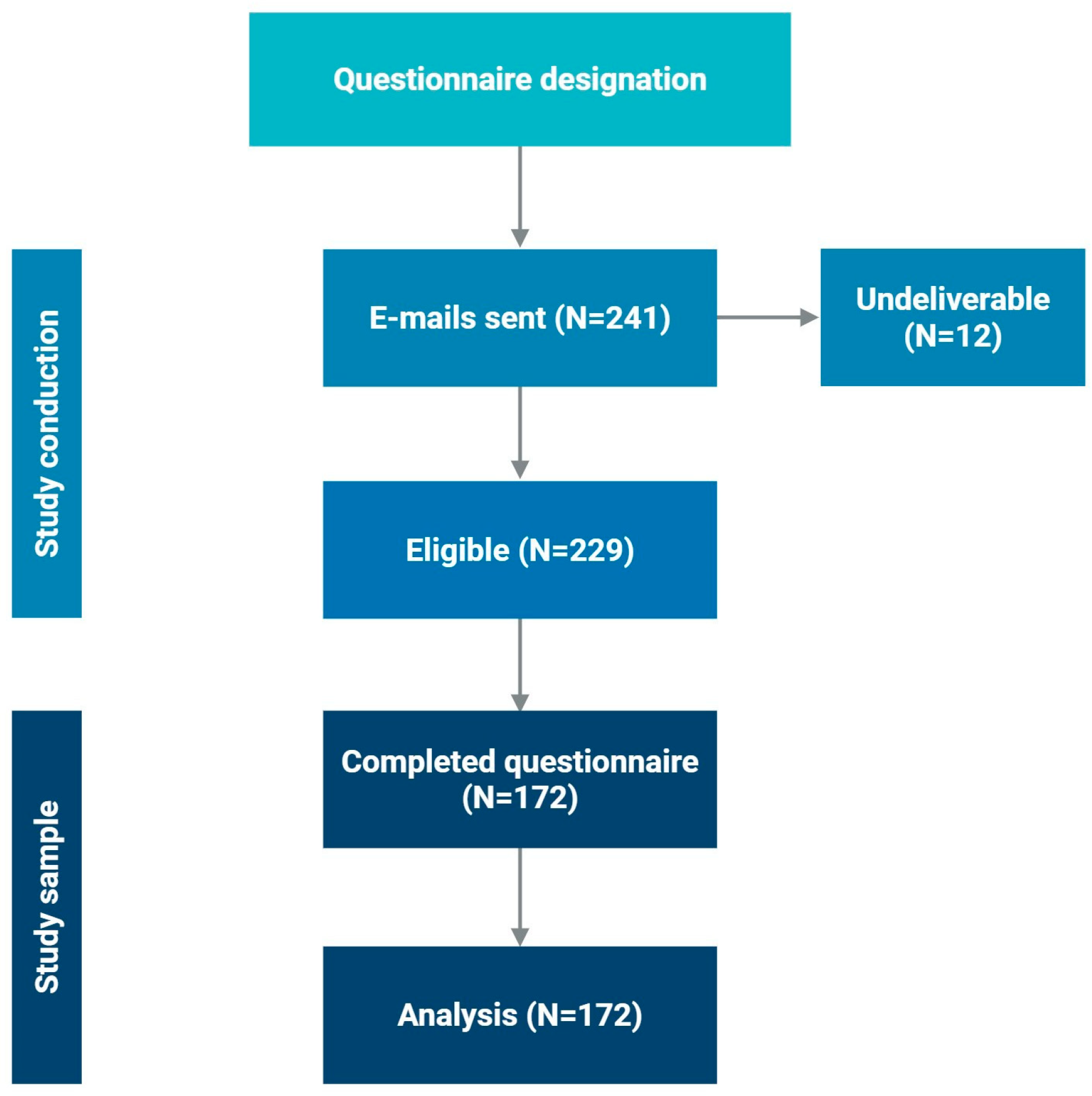

Emails were sent to 241 dentists, of whom 172 completed the questionnaire; 121 of them (70.3%) were females. Response rate was 71.4% (95% CI: 65.7–77.1%). Based on their birth years, we divided dentists into four groups. Overall, 9.3% of dentists were born between 1960 and 1969, 23.3% were born between 1970 and 1979, and 21.5% dentists were born between 1980 and 1989. Almost half of all dentists involved in this study were born between 1990 and 1999 (45.9%).

From the total number of dentists, as many as 145 (84.3%) were without specialization, while 30 (17.4%) had completed postgraduate studies.

As for questions related to bisphosphonates, 114 dentists (66.3%) reported having learned about bisphosphonates during their education, and 126 (73.3%) of dentists treated patients on bisphosphonate therapy. Almost all (N = 169; 98.3%) answered correctly on the question that before starting bisphosphonate therapy, the patient should be referred to a dentist for examination and treatment.

Only 32 dentists (18.6%) answered all questions about bisphosphonates correctly.

Table 1 shows the list of nine questions and statements used to test knowledge about bisphosphonates among participating dentists, and the rates of correct answers for each question.

The table presents the distribution of correct answers to individual knowledge questions regarding bisphosphonates, including the drug group to which they belong, their mechanism of action, indications, complications, risk factors, and clinical considerations, with an emphasis on invasive dental procedures. A total of 172 respondents completed the questionnaire. The mean total knowledge score (maximum 9 points) was 7.3 ± 1.4, corresponding to 81.5% correct responses overall. The median [IQR] knowledge score was 8 [

7,

8,

9], indicating generally high theoretical awareness of bisphosphonate therapy. However, considerable variation was observed between items, with the lowest accuracy noted for peri-procedural management before invasive dental procedures (38.4%). These findings highlight that although conceptual understanding is strong, practical aspects of patient management remain a key educational gap. Most dentists demonstrated good knowledge about bisphosphonates, correctly identifying their mechanism of action (94%), clinical indications (96%), and osteonecrosis of the jaw as the primary oral complication (92%). Knowledge was lower regarding the occurrence of complications in the mandible, the most frequently affected site (76%), as well as the risk associated with intravenous administration (78%). The lowest proportion of correct responses, however, was observed for management before invasive dental procedures (38%).

No statistically significant differences were observed in the number of correct answers across all questions based on gender (

p = 0.834), year of birth (

p = 0.408), year of graduation (

p = 0.516), and having completed postgraduate study (

p = 0.398). The highest percentage of respondents with correct answers was among those holding a postgraduate doctoral degree (27.8%), but this difference was not statistically significant (

p = 0.398). The table also shows that respondents born between 1980 and 1989 and those who graduated between 2006 and 2015 exhibited greater knowledge about bisphosphonates and their oral side effects (

Table 2).

Of all respondents, only 33 (19.2%) had previously taken a course on bisphosphonate therapy. Almost all respondents, 164 out of 172 (95.3%), expressed a desire for more education about the treatment and its side effects.

Finally, there were no statistically significant predictors of high knowledge in the questionnaire (≥75% correct) amongst the following independent variables: female sex (1.37 (0.69–2.71)), specialty training (1.98 (0.69–5.65)), ≤9 years since graduation (1.89 (0.83–4.28)), age ≤ 35 years (1.60 (0.69–3.73)), and completed doctoral postgraduate study (2.10 (0.60–7.37)) with good model-fit (

p = 0.266) (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

This study found satisfactory level of knowledge regarding bisphosphonates and their oral side effects among dental practitioners in Split-Dalmatia County, Croatia. IV administration of BP causes greater inhibition of bone remodeling and could lead more severe inflammation. Therefore, even if the duration of IV administration of BP is shorter than that of oral BP, the extent of the lesion could be more extensive. Therefore, the result suggests that the MRONJ after IV BP for cancer patients needs to be considered as different characteristics to oral BP group for osteoporosis patents [

13]. Also, AAOMS, in their position paper, stated that to estimate the risk for medications associated with MRONJ, the primary parameter to be considered is the therapeutic indication for treatment (e.g., malignancy or osteoporosis/osteopenia). The data suggest that antiresorptive medications (i.e., BPs and DMB) are associated with an increased risk for developing MRONJ. The risk of MRONJ is considerably higher in the malignancy group (<0.05% [

11]). This emphasizes the need for dental practitioners to recognize the potential risks of these medications, implement preventive measures, identify early signs of side effects, and know how to treat patients on bisphosphonate therapy. Almost 80% of dentists correctly identified bisphosphonates as antiresorptive drugs, while nearly all dentists correctly noted that the primary mechanism of action of bisphosphonates is osteoclast inhibition. Our findings differ significantly from a study conducted by de Lima et al. [

14] in Brazil, where only 29.8% of dental professionals and 39% of dental students accurately answered questions regarding the mechanism of action.

Most dentists (95.9%) recognized the indications for bisphosphonates (multiple myeloma, bone metastases of breast cancer, rheumatoid arthritis), demonstrating a very high level of awareness. In a similar study conducted by Bival et al. in Croatia in 2023, only 39.7% of dentists correctly listed all indications for bisphosphonate use [

20]. This notable difference in answer accuracy likely reflects the increasing availability of information and the growing knowledge about bisphosphonates in professional and scientific literature over the past few years.

Osteonecrosis of the jaw, correctly identified by almost all dentists in our study, is the most common oral complication of bisphosphonate therapy. A 2018 study by Patil et al. showed a significantly lower level of knowledge, with only 47.9% of dental practitioners recognizing osteonecrosis as a potential side effect in patients receiving bisphosphonate therapy [

21]. A similar study by de Lima et al. also found that only 40.4% of dental practitioners recognized BRONJ and its symptoms [

14].

The large majority of dentists (95.9%) correctly identified risk factors for BRONJ, such as dose, duration, and route of administration. In contrast, a study by de Lima et al. [

14] found that only 1.9% of dental practitioners could accurately recognize all bisphosphonate-related risk factors for BRONJ.

When asked about the procedure to follow in the event of planned invasive dental procedures such as extraction, alveotomy, or endodontic surgery in patients receiving bisphosphonate therapy, only 38.4% of respondents gave the correct answer—which is that if the patient has been on treatment for less than 4 years and is not receiving additional corticosteroid or angiogenic therapy, oral therapy does not need to be discontinued. A 2020 study conducted in Korea by Han yielded similar results, with 39.4% of dentists responding that they would discontinue bisphosphonate therapy 6 months before the planned invasive dental procedure, a response also given by 54.7% of our respondents [

22]. Similarly, a study by Alhussain et al. confirms these findings, showing that only 23% of respondents apply AAOMS guidelines when performing invasive dental procedures on patients taking bisphosphonates. In comparison, 50% would act incorrectly [

6]. Given the importance of proper management in planned invasive dental procedures for patients on bisphosphonate therapy, better results are expected, indicating a need for improvement in knowledge and highlighting the requirement for additional education.

Furthermore, 77.9% of dentists recognized that intravenous bisphosphonates are associated with a higher risk of oral complications, and 76.2% understood that these issues are more commonly observed in the lower jaw. In a study conducted by Patil et al. in 2018, fewer participants provided correct answers to the same questions, with only 38.5% correctly identifying that intravenous bisphosphonates carry a greater risk of oral complications, and 53.4% correctly stating that these complications are more often associated with the lower jaw [

21].

The exact names of the drugs (alendronate (Fosamax), zoledronate (Zometa), ibandronate (Bonviva), and risedronate (Sedrone) acid) belonging to the bisphosphonate group were correctly recognized by 83.1% of dentists in our study, which is in contrast to the results of the study by Al-Maweri et al. [

23], in which only 36% of dentists, specialists with many years of experience, recognized the correct names of drugs belonging to the bisphosphonate group.

Almost all respondents (98.3%) believe it is crucial to refer patients to a dentist for examination and treatment before starting bisphosphonate therapy. A similar study by Al-Maweri et al. [

23] found that 71.7% of respondents shared this view. These findings suggest that a significant portion of dental professionals in Split-Dalmatia County understand the importance of dental care before beginning bisphosphonate therapy. This aligns with the recommendations of the AAOMS, which highlight the importance of preventive dental preparation [

11].

The results indicate that 66.3% of respondents gained knowledge about using bisphosphonates during their university education, which is significantly higher than the 34.6% reported by de Lima et al. [

14]. However, the same study by de Lima et al. also found that 75% of dental students reported familiarity with the topic during their university education, suggesting potential progress in curricula and a growing focus on this subject.

During their work, 73.3% of respondents reported encountering patients on bisphosphonate therapy, which aligns with the results from a study by Han, where 65% of respondents indicated they had documented the use of bisphosphonates in their patients. These similar findings highlight the common occurrence of patients receiving bisphosphonate therapy in everyday dental practice, further underscoring the importance of educating dentists on the proper management of such patients [

22]. A recent review made by European authors highlights the same thing [

24]. To summarize, the 2019 paper by Schiodt et al. is noteworthy because it addresses the current challenges in managing medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ). It highlights a need for better diagnostic criteria, improved preventative strategies, and specific guidelines for different patient groups, particularly those on both antiresorptive drugs and endocrine therapy for cancer. The paper addresses the limitations in the available literature and emphasizes the importance of a comprehensive and tailored approach to both prevention and treatment [

25].

The study’s limitations are primarily related to the representativeness of the sample, both in terms of size and its characteristics, as well as the non-probabilistic sampling method, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the response rate may also introduce additional potential bias. Furthermore, using self-reported online data may not accurately reflect actual knowledge or competencies. The questionnaire consisted of multiple-choice questions, which may have facilitated answering and, in turn, impacted the findings. Also, social desirability bias, coverage error (e-mail frame) should be mentioned.

The results of this survey indicate a high level of awareness among respondents about the need for additional education on bisphosphonate therapy and its side effects, especially in the context of MRONJ prevention and early recognition. Although the majority of participants demonstrate a good theoretical understanding of the basic concepts, the results suggest a possible discrepancy between knowledge and its practical application in clinical practice. This pattern emphasizes the importance of targeted educational programs that not only expand knowledge but also encourage its consistent application in everyday work. Given the sample limitations and specific local context, these findings cannot be generalize d to the broader population without further research. Still, they provide valuable insight into the need for continuous professional development of dental practitioners in Croatia. Given that 95% of respondents expressed a desire for additional education on MRONJ, targeted educational interventions are recommended. Educational priorities should include: (1) peri-procedural management of patients on anti-resorptive therapy, (2) risk assessment by route of administration (IV vs. oral), and (3) recognition of early clinical signs of MRONJ. Suggested formats include online CPD modules, chairside checklists, and case-based workshops.