Oral Lesions in a Teaching Clinic: A Retrospective Study and Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Systematic Review

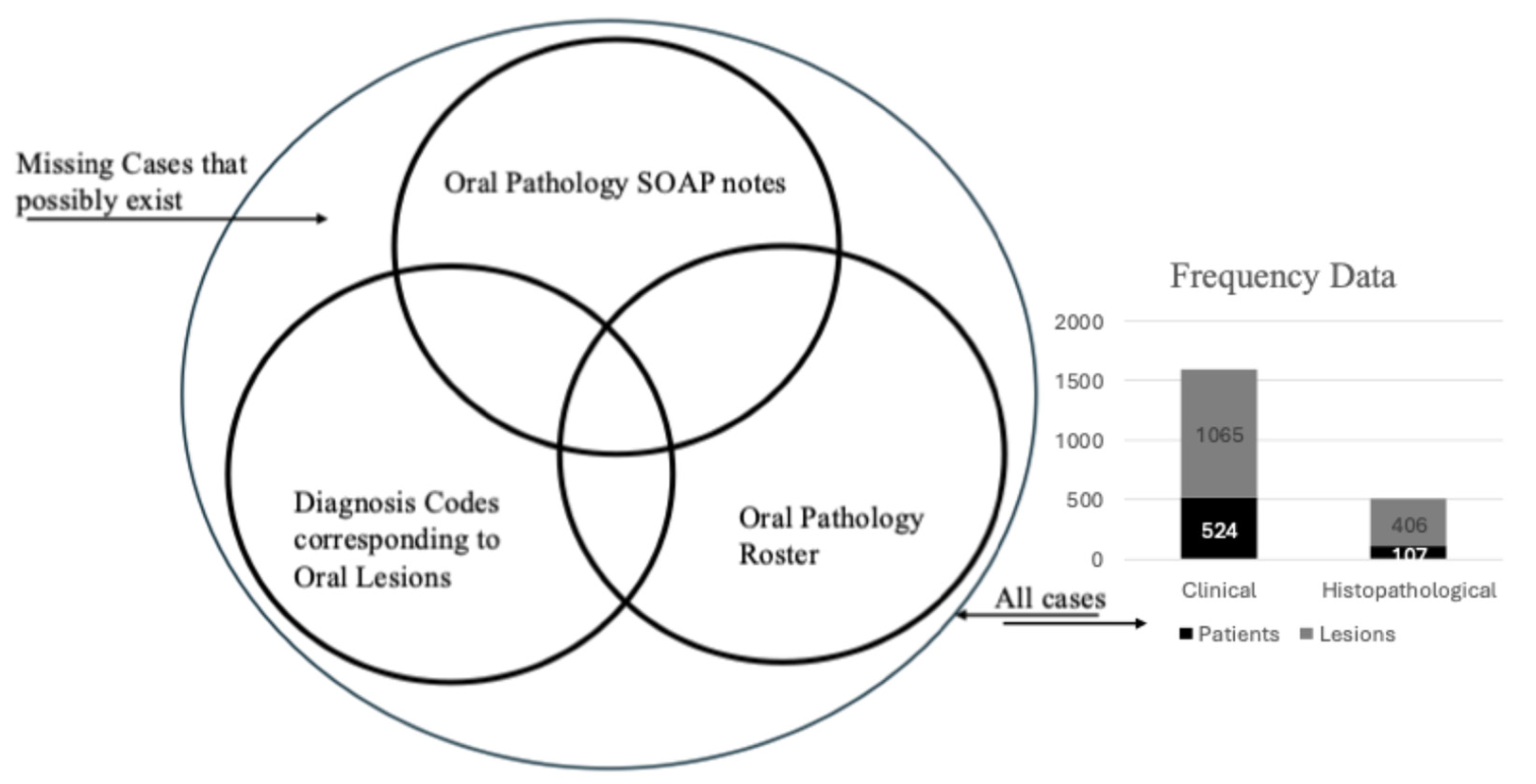

2.2. Retrospective Study

3. Results

3.1. Systematic Review

3.2. Retrospective Study—Analysis of Oral Pathology Data

4. Discussion

4.1. Systematic Review Key Points

4.2. Retrospective Study Comparison to Literature and Important Takeaways

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Levi, L.E.; Lalla, R.V. Dental Treatment Planning for the Patient with Oral Cancer. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 62, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, S.N. Oral pathology in the dental office: Survey of 20,575 biopsy specimens. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1968, 76, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weir, J.C.; Davenport, W.D.; Skinner, R.L. A diagnostic and epidemiologic survey of 15,783 oral lesions. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1987, 115, 439–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, South Australia, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Seo, B.; Hussaini, H.M.; Meldrum, A.M.; Rich, A.M. The relative frequency of paediatric oral and maxillofacial pathology in New Zealand: A 10-year review of a national specialist centre. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2020, 30, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, A.V.; Franklin, C.D. An analysis of oral and maxillofacial pathology found in adults over a 30-year period. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2006, 35, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ftouni, R.; AlJardali, B.; Hamdanieh, M.; Ftouni, L.; Salem, N. Challenges of Telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2022, 22, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, M.; Licari, F.W.; Hon, E.S. In an era of uncertainty: Impact of COVID-19 on dental education. J. Dent. Educ. 2021, 85, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, B.; Damm, D.; Allen, C.; Chi, A. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yakin, M.; Jalal, J.A.; Al-Khurri, L.E.; Rich, A.M. Oral and maxillofacial pathology submitted to Rizgary Teaching Hospital: A 6-year retrospective study. Int. Dent. J. 2016, 66, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mobeeriek, A.; Aldosari, A.M. Prevalence of oral lesions among Saudi dental patients. Ann. Saudi Med. 2009, 29, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhindi, N.; Sindi, A.; Binmadi, N.; Elias, W. A retrospective study of oral and maxillofacial pathology lesions diagnosed at the Faculty of Dentistry, King Abdulaziz University. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2019, 11, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulaganathan, G.; Babu, S.S.; Senthilmoorthy, M.; Prasad, V.; Kalaiselvan, S.; Kumar, R.S.A. Retrospective analysis of oral and maxillofacial biopsies: An institutional study. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2020, 12 (Suppl. 1), S468–S471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishat, R.; Jaiswal, M.M.; Kumari, N.; Jha, P.C.; Bhuyan, L.; Vinayam. A Study on Prevalence of Oral Mucosal Lesions in the Geriatric Population of Eastern India. Ann. Rom. Soc. Cell Biol. 2021, 25, 6772–6785. [Google Scholar]

- Das, K.; Nair, V.; Chanda, D. A Retrospective Study of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology Lesions Diagnosed at the Calcutta National Medical College & Hospital, Kolkata. Int. J. Med. Sci. Curr. Res. 2022, 5, 403–411. [Google Scholar]

- El Toum, S.; Cassia, A.; Bouchi, N.; Kassab, I. Prevalence and Distribution of Oral Mucosal Lesions by Sex and Age Categories: A Retrospective Study of Patients Attending Lebanese School of Dentistry. Int. J. Dent. 2018, 2018, 4030134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, J.; Brache, M.; Ogando, G.; Veras, K.; Rivera, H. Prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in an adult population from eight communities in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. Acta Odontológica Latinoam. 2021, 34, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, L.S.; Albuquerque, R.; Paiva, A.; Peña-Moral, J.; Amaral, J.B.; Lopes, C.A. A comparative analysis of oral and maxillofacial pathology over a 16-year period, in the north of Portugal. Int. Dent. J. 2017, 67, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, M.M.; Albuquerque, R.; Monteiro, M. Oral soft tissue biopsies in Oporto, Portugal: An eight year retrospective analysis. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2015, 7, e640–e648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, C.; Jones-Herrera, C.; Vargas, P.; Venegas, B.; Droguett, D. Oral diseases: A 14-year experience of a Chilean institution with a systematic review from eight countries. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2017, 22, e297–e306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, C.; Droguett, D.; Arenas-Márquez, M.J. Oral mucosal lesions in a Chilean elderly population: A retrospective study with a systematic review from thirteen countries. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2017, 9, e276–e283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, S.M.; Idris, A.M.; Vani, N.V.; Tubaigy, F.M.; Alharbi, F.A.; Sharwani, A.A.; Mikhail, N.T.; Warnakulasuriya, S. Retrospective analysis of biopsied oral and maxillofacial lesions in South-Western Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2017, 38, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, M.F.-L.; Kato, C.-D.-N.-A.-D.O.; Pereira, M.-J.-D.C.; Gomes, L.-T.-F.; Abreu, L.-G.; Fonseca, F.-P.; Mesquita, R.-A. Oral and maxillofacial lesions in older individuals and associated factors: A retrospective analysis of cases retrieved in two different services. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2019, 11, e921–e929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, A.C.R.F.; Bandeira, I.; Cardoso, J.A.; Pereira, M.C.M.C. Epidemiological study of lesions of the maxillofacial complex diagnosed by UNIME histopathology laboratory, Lauro de Freitas, Bahia. Rev. Odonto Cienc. 2019, 33, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho Mde, V.; Iglesias, D.P.; do Nascimento, G.J.; Sobral, A.P. Epidemiological study of 534 biopsies of oral mucosal lesions in elderly Brazilian patients. Gerodontology 2011, 28, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fattori, E.; Teixeira, D.D.S.; Figueiredo, M.A.Z.; Cherubini, K.; Salum, F.G. Stomatological disorders in older people: An epidemiological study in the Brazil southern. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2019, 24, e577–e582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akinyamoju, A.O.; Adeyemi, B.F.; Adisa, A.O.; Okoli, C.N. Audit of Oral Histopathology Service at a Nigerian Tertiary Institution over a 24-Year Period. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2017, 27, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyele, O.O.; Aborisade, A.; Adesina, O.M. Concordance between clinical and histopathologic diagnosis and an audit of oral histopathology service at a Nigerian tertiary hospital. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2019, 34, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, F.; Chen, P.H.; Chen, J.Y. Retrospective study of biopsied head and neck lesions in a cohort of referral Taiwanese patients. Head Face Med. 2014, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sixto-Requeijo, R.; Diniz-Freitas, M.; Torreira-Lorenzo, J.C.; García-García, A.; Gándara-Rey, J.M. An analysis of oral biopsies extracted from 1995 to 2009, in an oral medicine and surgery unit in Galicia (Spain). Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2012, 17, e16–e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ali, M.; Joseph, B.; Sundaram, D. Prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in patients of the Kuwait University Dental Center. Saudi Dent. J. 2013, 25, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofizadeh, N.; Bjerkehagen, B.; Solheim, T.; Sapkota, D.; Søland, T.M. The spectrum and frequency of histopathological diagnosis of oral diseases in Oslo: Implications to oral pathology syllabus. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2022, 27, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, P.; Upadhyaya, C.; Humagain, M.; Srii, R.; Chaurasia, N.; Dulal, S. Clinicopathological analysis of oral lesions-a hospital based retrospective study. Kathmandu Univ. Med. J. 2019, 17, 311–315. [Google Scholar]

- Moridani, S.G.; Shaahsavari, F.; Adeli, M.B. A 7-year retrospective study of biopsied oral lesions in 460 Iranian patients. RSBO 2015, 11, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantari, M.; Samani, A.A. A Survey of Oral and Maxillofacial Biopsies Over a 23-year Period in the Southeast of Iran. J. Dent. 2022, 23, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelloway, E.; Ha, W.N.; Dost, F.; Farah, C.S. A retrospective analysis of oral and maxillofacial pathology in an Australian adult population. Aust. Dent. J. 2014, 59, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, H.; Thippeswamy, S.; Gandhi, P.; Salgotra, V.; Choudhary, S.; Agarwal, R. A retrospective study to evaluate biopsies of oral and maxillofacial lesions. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2021, 13 (Suppl. 1), S116–S119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, M.M.; Abdul-Aziz, M.A.W.M.; Elchaghaby, M.A. A retrospective analysis of oral and maxillofacial pathological lesions in a group of Egyptian children over 21 years. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatnagar, P.; Rai, S.; Bhatnagar, G.; Kaur, M.; Goel, S.; Prabhat, M. Prevalence study of oral mucosal lesions, mucosal variants, and treatment required for patients reporting to a dental school in North India: In accordance with WHO guidelines. J. Fam. Community Med. 2013, 20, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Almeida, C.G.; Freitas, F.; Francisco, H.; Marques, J.A.; Carames, J. Oral biopsies in a Portuguese population: A 20-year clinicopathological study in a university clinic. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2022, 14, e1024–e1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, S.; Katoch, V.; Premlata, S.P. Prevalence of oral mucosal lesions: A prospective study. Int. J. Dent. Oral Sci. 2021, 8, 3682–3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajracharya, D.; Gupta, S.; Ojha, B.; Baral, R. Prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in a tertiary care Dental Hospital of Kathmandu. J. Nepal Med. Assoc. 2017, 56, 362–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumcu, G.; Cimilli, H.; Sur, H.; Hayran, O.; Atalay, T. Prevalence and distribution of oral lesions: A cross-sectional study in Turkey. Oral Dis. 2005, 11, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Algarni, T.; Alshareef, M.; Alhussain, A.; Alrashidi, K.; Alahmari, S. Prevalence of Oral Mucosal Lesions Among Patients Visiting Private University Dental Hospital, Riyadh. Saudi Arabia. Ann. Dent. Spec. 2023, 11, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byakodi, R.; Shipurkar, A.; Byakodi, S.; Marathe, K. Prevalence of oral soft tissue lesions in Sangli, India. J. Community Health 2011, 36, 756–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabir, H.; Irshad, M.; Durrani, S.H.; Sarfaraz, A.; Arbab, K.N.; Khattak, M.T. First comprehensive report on distribution of histologically confirmed oral and maxillofacial pathologies; a nine-year retrospective study. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2022, 72, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Zhou, Z.; Shen, X. Prevalence and distribution of oral mucosal lesions: A cross-sectional study in Shanghai, China. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2015, 44, 490–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovač-Kavčič, M.; Skalerič, U. The prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in a population in Ljubljana, Slovenia. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2000, 29, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, J.; Toner, M.; O’Regan, E.; Nunn, J. The spectrum of histological findings in oral biopsies. Ir. Med. J. 2019, 112, 1017. [Google Scholar]

- Rosebush, M.S.; Anderson, K.M.; Rawal, S.Y.; Mincer, H.H.; Rawal, Y.B. The oral biopsy: Indications, techniques and special considerations. J. Tenn. Dent. Assoc. 2010, 90, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Vered, M.; Wright, J.M. Update from the 5th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck Tumors: Odontogenic and Maxillofacial Bone Tumours. Head Neck Pathol. 2022, 16, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, B.C.F.; Sperandio, F.F.; Hanemann, J.A.C.; Pereira, A.A.C. New WHO odontogenic tumor classification: Impact on prevalence in a population. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2020, 28, e20190067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonoglou, G.N.; Sándor, G.K. Recurrence rates of intraosseous ameloblastomas of the jaws: A systematic review of conservative versus aggressive treatment approaches and meta-Analysis of non-randomized studies. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 43, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langton, S.G. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology: A Rationale for Diagnosis and Treatment. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2003, 41, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Title | Country | Year | Site | Methods | Population | Inclusion Criteria | Limitation | Number | Age | Lesion Categories | Lesion Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yakin 2016 [11] | Oral and maxillofacial pathology submitted to Rizgary Teaching Hospital: a 6-year retrospective study | Iraq | 2016 | Department of Histopathology, Rizgary Teaching Hospital | Histopathologic evaluation | Patients who had a biopsy taken between 2008 and 2013 | Site of lesion | N/A | 616 | 0–90 | 1. Mucosal and skin pathology (33.9%) 2. Benign tumors (24.2%) 3. Malignant tumors (16.2%) 4. Miscellaneous (11.0%) 5. Cysts (8.0%) 6. Salivary gland pathology (6.7%) | 1. Pyogenic granuloma (10.5%) 2. SCC (10.2%) 3. Fibroepithelial polyp (9.1%) 4. Pleomorphic adenoma (6.8%) 5. Haemangioma (3.9%) 6. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (3.7%) 7. Mucocele (3.4%) 8. Sialadenitis (3.2%) 9. Giant cell granuloma (3.1%) 10. Ameloblastoma (2.9%) |

| Al-Mobeeriek 2009 [12] | Prevalence of oral lesions among Saudi dental patients | Saudi Arabia | 2009 | Dental outpatients | Both | Adult patients admitted to the Oral Diagnostic Clinic at King Saud University, College of Dentistry | Older than 15 years | N/A | 383 | 15–73 | N/A | 1. Fordyce granules (25.6%) 2. Leukoedema (22.5%) 3. Traumatic ulcer (12.5%) 4. Fissured tongue (9.4%) 5. Torus palatinus (8.9%) 6. Frictional hyperkeratosis (6.0%) 7. Tongue tie (3.9%) 8. Hairy tongue (3.7%) 9. Melanosis (3.7%) 10. Nicotinic stomatitis (3.4%) |

| Alhindi 2019 [13] | A retrospective study of oral and maxillofacial pathology lesions diagnosed at the Faculty of Dentistry, King Abdulaziz University | Saudi Arabia | 2019 | Oral Pathology Laboratory | Histopathologic evaluation | Patients at King Abdulaziz University oral pathology laboratory | Specimens between 1996 and 2016 | N/A | N/A | 0–85 | 1. Reactive/adaptive lesions (20.1%) 2. Cystic lesions (17.6%) 3. Inflammatory lesions (12.5%) 4. Epithelial lesions (9.4%) 5. Benign mesenchymal (8.7%) 6. Miscellaneous lesions (7.6%) 7. Malignancy (5.7%) 8. Immune-mediated diseases (4.9%) 9. Salivary gland (4.9%) 10. Odontogenic tumor (3.7%) | 1. Radicular and residual cysts (11.0%) 2. Periapical granuloma (9.4%) 3. Fibroma (6.2%) 4. Hyperkeratosis and acanthosis (5.4%) 5. Fibroepithelial polyp (5.3%) 6. Pyogenic granuloma (5.2%) 7. Nonspecific inflammation (4.8%) 8. Lichen planus (4.4%) 9. SCC (3.8%) 10. Dentigerous cyst (3.1%) |

| Ulaganathan 2020 [14] | Retrospective analysis of oral and maxillofacial biopsies: An institutional study | India | 2020 | CSI Dental College records | Histopathologic evaluation | Patients who received biopsy between 2007 and 2018 | N/A | Lack of information, irrelevant diagnosis | 904 | 5–85 | N/A | 1. Traumatic fibroma (15.9%) 2. Periapical cyst (12.9%) 3. Pyogenic granuloma (9.5%) 4. Dysplasia (9.3%) 5. SCC (7.3%) 6. Ameloblastoma (5.3%) 7. Osteomyelitis (4.0%) 8. Lichen planus (3.5%) 9. Mucocele (3.5%) 10. Periapical granuloma (3.5%) |

| Nishat 2021 [15] | A Study on Prevalence of Oral Mucosal Lesions in the Geriatric Population of Eastern India | India | 2021 | The Oral Pathology Department of the Patna Government Hospital | Clinical examination | Patients aged 60 years and older attending the Oral Pathology Department | Clinical diagnostic features | Developmental conditions | N/A | 60–95 | 1. Pre-malignant lesions (55.6%) 2. Reactive lesions (22.7%) 3. Tongue lesions (19.5%) 4. Denture-related lesions (16.0%) 5. Immune-mediated lesions (14.3%) 6. Infectious lesions (14.1%) 7. Malignant lesions (3.3%) 8. Pigmented lesions (2.5%) | 1. Leukoplakia (19.0%) 2. Atrophic tongue (16.7%) 3. Oral submucous fibrosis (14.8%) 4. Lichen planus (14.3%) 5. Smoker’s palate (13.2%) 6. Traumatic ulcer (11.5%) 7. Angular cheilitis (9.6%) 8. Tobacco pouch keratosis (8.7%) 9. Candidiasis (7.9%) 10. Herpetic lesions (6.2%) |

| Das 2022 [16] | A retrospective study of oral and maxillofacial pathology lesions diagnosed at The Calcutta National Medical College & Hospital, Kolkata | India | 2022 | Department of Pathology, Calcutta National Medical College | Histopathologic evaluation | Patients who had visited the Oral Pathology department between 2017 and 2020 | N/A | N/A | 418 | 20–77 | 1. Reactive lesions (20.6%) 2. Cystic lesions (17.8%) 3. Inflammatory lesions (12.4%) 4. Epithelial lesions (9.5%) 5. Benign mesenchymal tumors (8.2%) 6. Malignant tumors (6.3%) 7. Immune-mediated diseases (5.1%) 8. Salivary gland pathology (4.9%) 9. Odontogenic tumors (3.6%) 10. Bone pathology (2.5%) | 1. Radicular and residual cysts (9.3%) 2. Periapical granuloma (9.3%) 3. Fibroepithelial polyp (6.5%) 4. Pyogenic granuloma (5.7%) 5. Hyperkeratosis and acanthosis (5.5%) 6. Fibroma (5.0%) 7. Inflammation (4.8%) 8. Lichen planus (4.6%) 9. SCC (3.8%) 10. Dentigerous cyst (3.4%) |

| ElToum 2018 [17] | Prevalence and Distribution of Oral Mucosal Lesions by Sex and Age Categories: A Retrospective Study of Patients Attending Lebanese School of Dentistry | Lebanon | 2018 | Medical records of the Lebanese School of Dentistry | Clinical examination | Patients attending the Lebanese University for dental treatments | Medical records between October 2014 and May 2015 | Lack of written information, not evaluated by a doctor of the pathology department | 178 | 10–92 | N/A | 1. Coated/hairy tongue (17.4%) 2. Melanotic macule (11.2%) 3. Gingivitis (9.6%) 4. Linea alba(6.2%) 5. Tongue depapillation (5.1%) 6. Leukoplakia (5.1%) 7. Traumatic fibroma (4.5%) 8. Frictional keratosis (3.9%) 9. Fissured tongue (3.9%) 10. Fordyce granules (3.9%) |

| Collins 2021 [18] | Prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in an adult population from eight communities in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic | Dominican Republic | 2021 | Volunteers from Santo Domingo communities | Clinical examination | Adults from eight Dominican Republic communities | General good health, 18 years or older | N/A | 248 | 18–86 | N/A | 1. Melanin pigmentation (25.0%) 2. Palatal/mandibular tori (20.2%) 3. Fordyce granules (7.9%) 4. Exostosis (5.6%) 5. Denture stomatitis (2.8%) 6. Nicotine stomatitis (2.5%) 7. Periodontal disease (2.3%) 8. Pericoronitis (2.2%) 9. Smoker melanosis (2.2%) 10. Leukoedema (2.2%) |

| Monteiro 2017 [19] | A comparative analysis of oral and maxillofacial pathology over a 16-year period, in the north of Portugal | Portugal | 2017 | The Pathology Department of the Hospital de Santo Antonio | Histopathologic evaluation | Patients from the Oporto community | N/A | Biopsies showing normal tissue; repeated biopsies of lesions already diagnosed, unclear or inconclusive cases | N/A | 3–100 | 1. Reactive lesions (21.1%) 2. Cystic lesions (20.1%) 3. Inflammatory lesions (19.8%) 4. Malignant neoplasms (15.0%) 5. Benign neoplasms (12.6%) 6. Premalignant lesions (5.1%) 7. Autoimmune/metabolic lesions (2.8%) 8. Developmental disorders (2.1%) 9. Infective lesions (1.4%) | 1. Fibroepithelial polyp (12.0%) 2. SCC (12.0%) 3. Inflammatory odontogenic cyst (8.0%) 4. Pleomorphic adenoma (4.0%) 5. Follicular cyst (3.0%) 6. Squamous cell papilloma (3.0%) 7. Non-specific ulcer (3.0%) 8. Mucocele (3.0%) 9. Chronic sialoadenitis (3.0%) 10. Pyogenic granuloma (3.0%) |

| Guedes 2015 [20] | Oral soft tissue biopsies in Oporto, Portugal: An eight year retrospective analysis | Portugal | 2015 | Pathology Department of the Hospital de Santo Antonio | Histopathologic evaluation | Patients at the Pathology Department who underwent oral biopsy between 1999 and 2006 | Definitive histopathological diagnosis | Unclear, missing, or inconclusive results | N/A | 3–100 | 1. Reactive lesions (28.3%) 2. Malignant neoplasms (19.6%) 3. Inflammation/infection (15.5%) 4. Benign neoplasms (8.9%) 5. Cystic lesions (6.8%) 6. Autoimmune/metabolic diseases (6.4%) 7. Vascular lesions (4.9%) 8. Normal tissue (3.8%) 9. Hamartomatous/congenital lesions (1.4%) | 1. Fibroepithelial hyperplasia (17.9%) 2. Epidermoid carcinoma (15.2%) 3. Mucocele (6.1%) 4. SCC (4.8%) 5. Angiomas/vascular abnormalities (4.6%) 6. Normal tissue (3.8%) 7. Non-specific ulcer (3.7%) 8. Leukoplakia (3.7%) 9. Lichen planus (3.3%) 10. Chronic inflammation (3.2%) |

| Rivera 2017 [21] | Oral diseases: a 14-year experience of a Chilean institution with a systematic review from eight countries | Chile | 2017 | University of Talca medical record database | Both | Patients treated at the University of Talca between 2001 and 2014 | Availability of both clinical and histopathological diagnoses | N/A | N/A | 4–97 | 1. Soft tissue tumors (23.2%) 2. Epithelial pathology (15.8%) 3. Salivary gland pathology (10.9%) 4. Dermatologic diseases (10.1%) 5. Facial pain and neuromuscular diseases (6.9%) 6. Allergies and immunologic diseases (6.2%) 7. Developmental defects (4.9%) 8. Fungal diseases (4.2%) 9. Pulp and periapical disease (3.2%) 10. Odontogenic cysts and tumors (2.3%) | 1. Irritation fibroma (10.2%) 2. Lichen planus (5.8%) 3. Mucocele (5.4%) 4. Burning mouth syndrome (4.5%) 5. Hemangioma (4.1%) 6. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis (4.1%) 7. Papilloma (3.8%) 8. Pyogenic granuloma (3.2%) 9. Melanin pigmentation (2.0%) 10. Nevus (2.0%) |

| Rivera 2017 [22] | Oral mucosal lesions in a Chilean elderly population: A retrospective study with a systematic review from thirteen countries | Chile | 2017 | The School of Dentistry, University of Talca | Both | Elderly patients from the oral pathology service | Presence of one clear clinical and histopathological diagnosis, | N/A | 277 | 61–97 | 1. Soft tissue tumors (28.9%) 2. Epithelial pathology (18.4%) 3. Facial pain and neuromuscular diseases (10.5%) 4. Dermatologic diseases (9.4%) 5. Fungal diseases (6.5%) 6. Physical and chemical injuries (6.1%) 7. Salivary gland pathology (5.8%) 8. Allergies and immunologic diseases (5.4%) 9. Developmental defects (3.6%) 10. Pulp and periapical disease (1.8%) | 1. Irritation fibroma (10.8%) 2. Hemangioma (7.2%) 3. Burning mouth syndrome (7.2%) 4. Oral lichen planus (4.3%) 5. Epulis fissuratum (4.3%) 6. Melanin pigmentation (4.0%) 7. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis (4.0%) 8. Vascular malformation (3.2%) |

| Saleh 2017 [23] | Retrospective analysis of biopsied oral and maxillofacial lesions in South-Western Saudi Arabia | Saudi Arabia | 2017 | King Fahad Central Hospital histopathology records | Histopathologic evaluation | Patients with oral lesions who attended the surgical biopsy service of King Fahad Central Hospital | All cases with oral lesions between 2006 and 2015 | N/A | 714 | 0–100 | 1. Malignant neoplasm (38.7%) 2. Inflammatory lesions (16.5%) 3. Reactive lesions (13.7%) 4. Non-inflammatory cysts (9.8%) 5. Benign tumors (8.7%) 6. Mucosal pathology (8.1%) 7. Benign odontogenic tumors (2.2%) 8. Miscellaneous lesions (2.1%) | 1. Squamous cell carcinoma (36.1%) 2. Pyogenic granuloma/mucocele (7.0%) 3. Mucocele/ranula (7.0%) 4. Epithelial hyperplasia (4.5%) 5. Chronic non-specific inflammation (4.3%) 6. Focal fibrous hyperplasia (2.5%) 7. Radicular cyst (2.2%) 8. Squamous cell papilloma (2.2%) 9. Sialadenitis (1.7%) 10. Pleiomorphic adenoma (1.7%) |

| Fonseca 2019 [24] | Oral and maxillofacial lesions in older individuals and associated factors: A retrospective analysis of cases retrieved in two different services | Brazil | 2019 | The Oral Medicine clinic and laboratory service at the Department of Oral Pathology and Surgery of the Federal University of Minas Gerais | Both | Patients aged 60 or older attending the Oral Medicine clinic between 2001 and 2017 | N/A | Inadequate information, inconclusive diagnosis | N/A | 60 | 1. Inflammatory/reactive lesion (40.4%/44.2%) 2. Infectious diseases (18.5%/4.2%) 3. Variations in normality (10.8%/2.9%) 4. Potentially malignant disorders (7.4%/13.3%) 5. Malignant neoplasms (7.1%/17.6%) 6. Immunological diseases (5.7%/3.0%) 7. Benign neoplasms (3.4%/5.4%) 8. Non-neoplastic bone lesions (3.1%/1.5%) 9. Pigmented lesions (2.1%/1.4%) 10. Odontogenic/non-odontogenic cysts (1.5%/6.5%) Oral Medicine clinic %/Laboratory % | 1. Inflammatory fibrous hyperplasia (24.3/33.6%) 2. Candidiasis/SCC (15.6/15.2%) 3. Varices/leukoplakia (7.2/12.2%) |

| Da Silva 2019 [25] | Epidemiological study of lesions of the maxillofacial complex diagnosed by UNIME histopathology laboratory, Lauro de Freitas, Bahia | Brazil | 2019 | Histopathological data from the dental clinics of the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences and Health of the Metropolitan Union of Education and Culture | Histopathologic evaluation | Dental clinic patients from the Lauro de Freitas region | Oral lesions diagnosed and filed between 2003 and 2014 | Inadequate diagnosis or information | 434 | 6–87 | 1. Non-neoplastic proliferative processes (24.2%) 2. Odontogenic cysts (17.5%) 3. Miscellaneous (10.1%) 4. Bone lesions (6.7%) 5. Odontogenic tumors (5.3%) 6. Inflammatory lesions (5.3%) 7. Lesions associated with the root apex (4.8%) 8. Salivary gland lesions (4.4%) 9. Non-odontogenic tumors (3.9%) 10. Malignancies (3.9%) | 1. Inflammatory fibrous hyperplasia (13.1%) 2. Radicular cyst (10.8%) 3. N/A |

| Carvalho 2011 [26] | Epidemiological study of 534 biopsies of oral mucosal lesions in elderly Brazilian patients | Brazil | 2011 | Oral Pathology Laboratory | Histopathologic evaluation | Elderly Brazilian patients | Aged 60 or over | N/A | 534 | 60–99 | 1. Non-neoplastic (66.1%) 2. Benign (15.9%) 3. Malignant (10.5%) 4. Potentially malignant (7.5%) | 1. Fibrous hyperplasia (19.1%) 2. Chronic inflammation (9.2%) 3. SCC (7.9%) 4. Odontogenic cyst (6.0%) 5. Epithelial dysplasia (5.2%) |

| Fattori 2019 [27] | Stomatological disorders in older people: An epidemiological study in the Brazil southern | Brazil | 2019 | Service of Stomatology and Prevention of Oral Maxillofacial Cancer of Sao Lucas Hospital | Both | Elderly patients of a stomatology service in southern Brazil | Older than 60 years | Incomplete information | N/A | 60–97 | All diagnoses: 1. Variations in normality (44.5%) 2. Local fungal infection (26.1%) 3. Reactive inflammatory lesions (24.6%) 4. Burning mouth syndrome (14.9%) 5. Benign neoplasms (12.4%) 6. Autoimmune diseases (12.3%) 7. Malignant epithelial neoplasms (7.2%) 8. Anemias (4.3%) 9. Salivary gland pathology (2.7%) 10. Odontogenic cysts and tumors (0.9%) | Biopsied cases only: 1. SCC (30.2%) 2. Fibroepithelial hyperplasia (28.2%) 3. Hyperkeratosis and acanthosis (5.0%) 4. Fibrous proliferation (3.0%) 5. Lichen planus (2.5%) 6. Papilloma (2.3%) 7. Pyogenic granuloma (2.3%) 8. Fibroma (2.0%) 9. Peripheral giant cell granuloma (2.0%) 10. Epithelial dysplasia (1.6%) |

| Akinyamoju 2017 [28] | Audit of Oral Histopathology Service at a Nigerian Tertiary Institution over a 24-Year Period | Nigeria | 2017 | Oral Pathology laboratory | Histopathologic evaluation | Patients of the Ibadan University Hospital | All biopsies submitted between 1990–2014 | Inadequate information, imprecise diagnosis, immunohistochemistry cases | N/A | N/A | 1. Reactive lesions: 411 (23.1%) 2. Odontogenic tumors: 321 (18.1%) 3. Epithelial tumors: 220 (12.4%) 4. Salivary Gland tumors: 163 (9.2%) 5. Soft tissue tumors: 159 (8.9%) 6. Fibro-osseous lesions: 149 (8.4%) 7. Pulp and periapical lesions: 120 (6.7%) 8. Cystic Lesions: 70 (3.9%) 9. Heamatolymphoid neoplasms: 56 (3.1%) 10. Salivary gland diseases: 33 (1.9%) | 1. Ameloblastoma: 204 (11.5%) 2. SCC: 185 (10.4%) 3. Pyogenic granuloma: 151 (8.5%) 4. Ossifying fibroma: 70 (3.9%) 5. Chronic inflammation: 64 (3.6%) 6. Apical cyst: 61 (3.4%) 7. Apical granuloma: 56 (3.1%) 8. Fibromyxoma 51 (2.9%) 9. Fibroma: 50 (2.8%) 10. Fibrous dysplasia (2.8%) |

| Soyele 2019 [29] | Concordance between clinical and histopathologic diagnosis and an audit of oral histopathology service at a Nigerian tertiary hospital | Nigeria | 2019 | Oral Pathology and Diagnosis Units, Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospital Complex | Histopathologic evaluation | Patients with biopsies submitted between 2008–2017 | N/A | Lack of clinical impression, ambiguous diagnosis, inadequate information | 592 | 0–94 | 1. Odontogenic tumors (25.3%) 2. Reactive lesions (12%) 3. Fibro-osseous lesions (10.3%) 4. Epithelial tumors (10%) 5. Cystic lesions (8.8%) 6. Salivary gland pathology (7.5%) 7. Microbial/inflammatory diseases (6.1%) 8. Hemato-lymphoid neoplasms (2.7%) 9. Pulp and periapical lesions (2.5%) 10. Giant cell lesions (2.2%) | N/A |

| Lei 2014 [30] | Retrospective study of biopsied head and neck lesions in a cohort of referral Taiwanese patients | Taiwan | 2014 | Oral Pathology Department records | Histopathologic evaluation | Taiwanese patients who received head/neck biopsy between 2000 and 2011 | Diagnosed cases | Normal tissues, non-specific findings | 37,210 | 0–99 | 1. Premalignant lesions (38.7%) 2. Inflammatory/infective lesions (31.6%) 3. Non-odontogenic malignant lesions (16.2%) 4. Odontogenic cysts (6.1%) 5. Benign non-odontogenic tumors (4.4%) 6. Miscellaneous (1.5%) 7. Benign odontogenic tumors (1.2%) 8. Non-odontogenic cysts (0.25%) | 1. SCC (13.3%) 2. Hyperkeratosis (12.8%) 3. Epithelial dysplasia (7.8%) 4. Candidiasis (6.8%) 5. Oral submucous fibrosis (6.7%) 6. Epithelial hyperplasia (6.4%) 7. Verrucous hyperplasia (5.0%) 8. Inflammation (4.9%) 9. Radicular cyst (4.6%) 10. Apical granuloma (3.8%) |

| Sixto-Requeijo 2012 [31] | An analysis of oral biopsies extracted from 1995 to 2009, in an oral medicine and surgery unit in Galicia (Spain) | Spain | 2012 | The Oral Medicine, Oral Surgery and Implantology unit at the University of Santiago de Compostela | Histopathologic evaluation | Patients of the University of Santiago | All patients who underwent biopsy between 1995 and 2009 | Multiple biopsies, missing information | 562 | 5–96 | 1. Mucosal pathology (37.9%) 2. Odontogenic cysts (27.4%) 3. Connective tissue pathology (13.4%) 4. Salivary gland pathology (5.3%) 5. Periodontal pathology (4.0%) 6. Miscellaneous (3.9%) 7. Malignant tumor (3.9%) 8. Dental pathology (2.8%) 9. Bone pathology (1.1%) 10. Odontogenic tumor (0.5%) | 1. Radicular cysts (16.7%) 2. Leukoplakia (15.5%) 3. Lichen planus (14.1%) 4. Fibroma (11.4%) 5. Dentigerous cyst (9.4%) 6. Mucocele (4.3%) 7. Papilloma (3.7%) 8. SCC (3.4%) 9. Periapical granuloma (2.8%) 10. Pyogenic granuloma (2.2%) |

| Ali 2013 [32] | Prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in patients of the Kuwait University Dental Center | Kuwait | 2013 | Kuwait University Dental Center | Clinical examination | New patients of the Kuwait University Dental Center admissions clinic | New patients | N/A | 530 | N/A | 1. White lesions (47.7%) 2. Pigmented lesions (20.0%) 3. Exophytic lesions (18.9%) 4. Miscellaneous (5.3%) 5. Red lesions (4.4%) 6. Ulcerative lesions (3.7%) | 1. Fordyce granules (20.4%) 2. Linea alba (11.4%) 3. Generalized pigmentation (11.2%) 4. Hairy tongue (5.6%) 5. Leukoedema (5.4%) 6. Frictional keratosis (5.3%) 7. Irritation fibroma (4.9%) 8. Torus/exostoses (3.7%) 9. Fissured tongue (3.3%) 10. Frenal tag (2.5%) |

| Sofizadeh 2022 [33] | The spectrum and frequency of histopathological diagnosis of oral diseases in Oslo: Implications to oral pathology syllabus | Norway | 2023 | Department of Pathology, Oslo University Hospital | Histopathologic evaluation | Patients referred to the Department of Pathology between 2015 and 2016 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1. Cysts/granulomas/dental follicles (43%) 2. Benign tumors and reactive lesions (27%) 3. Vesiculobullous lesions (17%) 4. Salivary gland pathologies (7%) 5. Jaw lesions (4%) 6. Malignant tumors (1%) 7. Pigmented lesions (1%) 8. Odontogenic tumors (1%) | 1. Periapical granuloma (16%) 2. Fibromas (12%) 3. Radicular cysts (12%) 4. Dentigerous cysts (8%) 5. Mucocele (4%) 6. Lichen planus (4%) 7. Hyperplastic dental follicles (3%) 8. Papilloma (3%) 9. Odontogenic keratocysts (2%) 10. Osteonecrosis of the jaw (2%) |

| Poudel 2019 [34] | Clinicopathological Analysis of Oral Lesions-A hospital based retrospective study | Nepal | 2019 | The Department of Oral Pathology, Dhulikhel Hospital | Histopathologic evaluation | Patients in the central east of Nepal | All diagnosed oral lesions between January 2016 and December 2017 | Insufficient clinical details, inconclusive biopsies, salivary gland lesions | 237 | 2–85 | 1. Odontogenic cysts (20.7%) 2. Benign lesions (17.3%) 3. Malignant lesions (16.9%) 4. Non-odontogenic cyst/pseudocyst (14.7%) 5. Reactive lesions (8.0%) 6. Miscellaneous (7.4%) 7. Odontogenic tumor (5.0%) 8. Premalignant lesions (2.0%) | 1. Mucocele (13.1%) 2. SCC (12.7%) 3. Fibroma (8.0%) 4. Pyogenic granuloma (7.6%) 5. Radicular cyst (7.6%) 6. Odontogenic keratocyst (6.3%) 7. Dentigerous cyst (5.5%) 8. Ameloblastoma (4.2%) 9. Periapical granuloma (3.4%) 10. Hemangioma (3.0%) |

| Moridani 2015 [35] | A 7-year retrospective study of biopsied oral lesions in 460 Iranian patients | Iran | 2014 | The Oral and Maxillofacial department of the Islamic Azad University | Histopathologic evaluation | Patients and referrals from North-East Tehran | N/A | N/A | 460 | 3–89 | 1. Reactive lesions (21.5%) 2. Odontogenic cysts (17.4%) 3. Pulp and periapical lesions (15.6%) 4. Immune-mediated lesions (5.4%) 5. Bone pathology (5.0%) 6. Odontogenic tumors (5%) 7. Epithelial lesions (3.9%) 8. Salivary gland diseases (2.0%) 9. Malignant epithelial tumors (1.5%) 10. Benign mesenchymal tumors (1.5%) | 1. Odontogenic keratocyst (7.4%) 2. Radicular cyst (7.4%) 3. Irritation fibroma (6.3%) 4. Dentigerous cyst (5.4%) 5. Periapical granuloma (5.4%) 6. Lichen planus (4.3%) 7. Epulis fissuratum (4.1%) 8. Pyogenic granuloma (3.3%) 9. Ameloblastoma (3.0%) 10. Residual cyst (2.2%) |

| Kalantari 2022 [36] | A Survey of Oral and Maxillofacial Biopsies Over a 23-year Period in the Southeast of Iran | Iran | 2022 | Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Kerman Faculty of Dentistry | Histopathologic evaluation | Patients referred to the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology | Biopsies taken between July 1997 and July 2020 | Normal tissue present, indefinite diagnosis, repeated biopsy | N/A | 0–105 | 1. Reactive lesions (34.6%) 2. Immune-mediated (20.7%) 3. Odontogenic cysts (12.6%) 4. Tooth and periodontal-related lesions (4.4%) 5. Inflammatory and infectious lesions (3.1%) 6. Osseous lesions (2.4%) 7. Salivary gland lesions (2.4%) 8. Pigmented lesions (2.3%) 9. Non-odontogenic cysts (0.5%) | 1. Lichen planus (18.1%) 2. Pyogenic granuloma (10.1%) 3. Irritation fibroma (9.6%) 4. Radicular cyst (7.6%) 5. Peripheral ossifying fibroma (4.0%) 6. SCC (3.9%) 7. Hyperkeratosis (3.7%) 8. Periapical granuloma (3.4%) 9. Epulis fissuratum (3.4%) 10. Dentigerous cyst (2.9%) |

| Kelloway 2014 [37] | A retrospective analysis of oral and maxillofacial pathology in an Australian adult population | Australia | 2014 | The University of Queensland Oral Pathology Service | Histopathologic evaluation | Patients of the Oral Pathology service | Patients 17 years of age or older | Lack of age, inconclusive diagnosis | N/A | N/A | 1. Mucosal pathology (37.2%) 2. Odontogenic cyst (16.3%) 3. Dental pathology (14.5%) 4. Gingival and periodontal pathology (7.6%) 5. Miscellaneous pathology (7.4%) 6. Bone and TMJ pathology (3.8%) 7. Salivary gland pathology, excluding tumors (2.9%) 8. Malignant tumors (2.7%) 9. Odontogenic tumors and hamartomas (2.6%) 10. Normal tissue (2.2%) | 1. Fibrous hyperplasia (15.2%) 2. Chronic periapical granuloma (9.6%) 3. Radicular cyst (9.5%) 4. Dentigerous cyst (4.1%) 5. Fibroepithelial polyp (4.0%) 6. Squamous papilloma (2.8%) 7. Fibrous epulis (2.7%) 8. Fibrous hyperplasia (2.5%) 9. Normal tissue (2.2%) 10. Pyogenic granuloma (2.1%) |

| Singh 2021 [38] | A Retrospective Study to Evaluate Biopsies of Oral and Maxillofacial Lesions | Turkey | 2021 | Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Faculty of Dentistry, Kocaeli University | Histopathologic evaluation | Patients who attended the Faculty of Dentistry over 2014–2018 | N/A | N/A | 475 | 7–88 | 1. Odontogenic cysts (71.6%) 2. Bone tumors (15.8%) 3. Odontogenic tumors (10.9%) 4. Malignancies (1.7%) | 1. Radicular cysts (45.5%) 2. Dentigerous cysts (16.2%) 3. Giant cell granulomas (7.4%) 4. Odontogenic keratocysts (4.8%) 5. Nasopalatine duct cyst (4.6%) 6. Odontoma (4.0%) 7. Ossifying fibroma (3.8%) 8. Pyogenic granuloma (3.2%) 9. Osteoma (2.9%) 10. Ameloblastoma (1.9%) |

| Category | N | Relative Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| 283 | 26.6% |

| 232 | 21.8% |

| 196 | 18.5% |

| 96 | 9.0% |

| 88 | 8.3% |

| 49 | 4.6% |

| 47 | 4.4% |

| 26 | 2.5% |

| 13 | 1.2% |

| 13 | 1.2% |

| 9 | 0.8% |

| 7 | 0.7% |

| 3 | 0.2% |

| 2 | 0.2% |

| Total | 1065 | 100% |

| Diagnosis | Number | Frequency | Diagnosis | Number | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epithelial atypia b | 37 | 9.11% | Acute inflammation c | 2 | 0.49% |

| Hyperorthokeratosis b | 36 | 8.87% | Subepithelial clefting f | 2 | 0.49% |

| Epithelial dysplasia (mild to moderate) b | 35 | 8.62% | Ulcerative granuloma c | 1 | 0.25% |

| Hyperkeratosis b | 29 | 7.14% | Stromal eosinophilia c | 1 | 0.25% |

| Chronic inflammation b | 25 | 6.16% | Spongiosis b | 1 | 0.25% |

| Acanthosis b | 24 | 5.91% | Reactive chronic inflammatory infiltrate c | 1 | 0.25% |

| Epithelial atrophy b | 19 | 4.68% | Psoriasiform mucositis d | 1 | 0.25% |

| Hyperparakeratosis b | 15 | 3.69% | Polyclonal plasmacytic inflammation c | 1 | 0.25% |

| Lichenoid mucositis d | 11 | 2.71% | Pleomorphic adenoma h | 1 | 0.25% |

| Lichenoid inflammation d | 11 | 2.71% | Phlebolith a | 1 | 0.25% |

| Candidiasis g | 10 | 2.46% | Peripheral giant cell granuloma c | 1 | 0.25% |

| Chronic mucositis d | 10 | 2.46% | Parulis k | 1 | 0.25% |

| Squamous papilloma g | 9 | 2.22% | Papillary hyperplasia c | 1 | 0.25% |

| Irritation fibroma c | 8 | 1.97% | Osteitis c | 1 | 0.25% |

| Ulceration c | 7 | 1.72% | Organizing thrombus a | 1 | 0.25% |

| SCC b | 6 | 1.48% | Neurofibroma e | 1 | 0.25% |

| MMP d | 6 | 1.48% | Nasopalatine duct cyst l | 1 | 0.25% |

| Focal fibrous hyperplasia c | 6 | 1.48% | Melanosis b | 1 | 0.25% |

| Verrucous carcinoma b | 5 | 1.23% | Lymphoid stroma c | 1 | 0.25% |

| Varix a | 5 | 1.23% | Lymphoid hyperplasia c | 1 | 0.25% |

| Dysplasia (severe) b | 5 | 1.23% | Lymphoid aggregate with follicle c | 1 | 0.25% |

| Verrucous hyperplasia b | 4 | 0.99% | Hypergranulosis b | 1 | 0.25% |

| Sialadenitis h | 4 | 0.99% | Hemorrhage c | 1 | 0.25% |

| Inflammatory fibrous hyperplasia c | 4 | 0.99% | Granulomatous inflammation f | 1 | 0.25% |

| Pyogenic granuloma c | 3 | 0.74% | Giant cell fibroma c | 1 | 0.25% |

| Interface mucositis d | 3 | 0.74% | Frictional trauma b | 1 | 0.25% |

| Granulation tissue c | 3 | 0.74% | Focal abscess k | 1 | 0.25% |

| Foreign body reaction c | 3 | 0.74% | Fibrous tumor e | 1 | 0.25% |

| Actinic cheilitis b | 3 | 0.74% | Fibroblast atypia e | 1 | 0.25% |

| Oral fibroma c | 2 | 0.49% | Fibroepithelial polyp c | 1 | 0.25% |

| Mucocele h | 2 | 0.49% | Exogenous foreign material c | 1 | 0.25% |

| Melanotic macule b | 2 | 0.49% | Epithelial proliferation b | 1 | 0.25% |

| Lichen Planus f | 2 | 0.49% | Chronic periodontitis i | 1 | 0.25% |

| Hyperplastic squamous mucosa b | 2 | 0.49% | Cauterization artifact c | 1 | 0.25% |

| Fungal infection g | 2 | 0.49% | Benign salivary gland tumor h | 1 | 0.25% |

| Chronic ulcer c | 2 | 0.49% | Benign salivary gland lobuli h | 1 | 0.25% |

| Carcinoma in-situ b | 2 | 0.49% | Atypical epithelial proliferation b | 1 | 0.25% |

| Bone sequestrum j | 2 | 0.49% | Amalgam tattoo c | 1 | 0.25% |

| Bacterial infection g | 2 | 0.49% | |||

| Total | 406 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wandzura, L.; Sperandio, M.; Hamilton, M.; Sperandio, F.F. Oral Lesions in a Teaching Clinic: A Retrospective Study and Systematic Review. Oral 2025, 5, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5030069

Wandzura L, Sperandio M, Hamilton M, Sperandio FF. Oral Lesions in a Teaching Clinic: A Retrospective Study and Systematic Review. Oral. 2025; 5(3):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5030069

Chicago/Turabian StyleWandzura, Luke, Michelle Sperandio, Melanie Hamilton, and Felipe F. Sperandio. 2025. "Oral Lesions in a Teaching Clinic: A Retrospective Study and Systematic Review" Oral 5, no. 3: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5030069

APA StyleWandzura, L., Sperandio, M., Hamilton, M., & Sperandio, F. F. (2025). Oral Lesions in a Teaching Clinic: A Retrospective Study and Systematic Review. Oral, 5(3), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5030069