Experiences and Attitudes Toward the Treatment of Patients with Mental Disorders Among Dentists in Croatia: A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Questionnaire

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GP | general practitioner |

| STROBE | Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

| MAO | monoamine oxidase |

| MAOIs | monoamine oxidase inhibitors |

References

- Stein, D.J.; Palk, A.C.; Kendler, K.S. What is a mental disorder? An exemplar-focused approach. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 894–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stimac, D.; Pavic Simetin, I.; Istvanovic, A. Early recognition of mental health problems in Croatia. Eur. J. Public. Health 2019, 29 (Suppl. S4), ckz186.569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukićević, T.; Draganić, P.; Škribulja, M.; Puljak, L.; Došenović, S. Consumption of psychotropic drugs in Croatia before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A 10-year longitudinal study (2012–2021). Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2024, 59, 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishu, M.P.; Aggarwal, V.; Shiers, D.; Peckham, E.; Johnston, G.; Joury, E.; Chew-Graham, C.A.; Goodall, K.; Elliott, E.; French, P.; et al. Developing a Consensus Statement to Target Oral Health Inequalities in People With Severe Mental Illness. Health Expect. 2024, 27, e14163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Wu, J.; Aggarwal, V.R.; Shiers, D.; Doran, T.; Palmier-Claus, J. Investigating the relationship between oral health and severe mental illness: Analysis of NHANES 1999–2016. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghaie, H.; Kisely, S.; Forbes, M.; Sawyer, E.; Siskind, D.J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between poor oral health and substance abuse. Addiction 2017, 112, 765–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratto, G.; Manzon, L. Use of psychotropic drugs and associated dental diseases. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2014, 48, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, J.T.; Greuter, C.; Surber, C. Antidepressants relevant to oral and maxillofacial surgical practice. Ann. Maxillofac. Surg. 2013, 3, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.B. Dental care for the patient with bipolar disorder. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2003, 69, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mishu, M.P.; Faisal, M.R.; Macnamara, A.; Sabbah, W.; Peckham, E.; Newbronner, L.; Gilbody, S.; Gega, L. A qualitative study exploring the barriers and facilitators for maintaining oral health and using dental services in people with severe mental illness: Perspectives from service users and service providers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 4344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćelić, R.; Braut, V.; Petričević, N. Influence of depression and somatization on acute and chronic orofacial pain in patients with single or multiple TMD diagnoses. Coll. Antropol. 2011, 35, 709–713. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Poornachitra, P.; Narayan, V. Management of dental patients with mental health problems in special care dentistry: A practical algorithm. Cureus 2023, 15, e34809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kooyman, I.; Schene, A.H.; Moritz, S. Course of Violence in Patients With Schizophrenia: Relationship to Clinical Symptoms and Treatment Approaches. Schizophr. Bull. 2020, 37, 921–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, T.; Green, D.; Walker, S.; O’Brien, M. Substance use and risk of aggression in patients with severe mental illness: A review. Br. J. Psychiatry 2020, 217, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Dental Association. Meeting the dental needs of patients with depression. ADA News. 10 November 2023. Available online: https://adanews.ada.org/huddles/meeting-the-dental-needs-of-patients-with-depression (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- van den Heuvel, J.; Plasschaert, A. Lifelong learning in dentistry; from quality assurance to quality development. Community Dent. Health 2005, 22, 130–132. [Google Scholar]

- Cuschieri, S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2019, 13 (Suppl S1), S31–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, W.G.; Averett, P.E.; Benjamin, J.; Nowlin, J.P.; Lee, J.G.; Anand, V. Barriers to and facilitators of oral health among persons living with mental illness: A qualitative study. Psychiatr. Serv. 2021, 72, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKibbin, C.L.; Kitchen-Andren, K.A.; Lee, A.A.; Wykes, T.L.; Bourassa, K.A. Oral health in adults with serious mental illness: Needs for and perspectives on care. Community Ment. Health J. 2015, 51, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Sheikh, S.; Rashmi, N.C.; Aggarwal, A.; Bansal, R. Assessment of the awareness of dental professionals regarding identification and management of dental patients with psychological problems in routine dental operatory: A survey. Oral Health Dent. Manag. 2014, 13, 435. [Google Scholar]

- Teoh, C.X.W.; Thng, M.; Lau, S.; Taing, M.W.; Chaw, S.Y.; Siskind, D.; Kisely, S. Dry mouth effects from drugs used for depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, and bipolar mood disorder in adults: Systematic review. BJPsych Open 2023, 9, e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisely, S.; Baghaie, H.; Lalloo, R.; Siskind, D.; Johnson, N.W. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between poor oral health and severe mental illness. Psychosom. Med. 2015, 77, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Official Gazette. Code of Dental Ethics and Deontology; Official Gazette: Poreč, Croatia, 2019; Available online: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/full/2019_07_67_1361.html (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- Turner, E.; Berry, K.; Aggarwal, V.R. Oral health self-care behaviours in serious mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2022, 145, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monda, M.; Costacurta, M.; Maffei, L.; Docimo, R. Oral manifestations of eating disorders in adolescent patients. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2022, 23, 123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Valeriani, L.; Frigerio, F.; Piciocchi, C.; Piana, G.; Montevecchi, M.; Donini, L.M.; Mocini, E. Oro-dental manifestations of eating disorders: A systematic review. J. Eat. Disord. 2024, 12, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisely, S.; Sawyer, E.; Siskind, D.; Lalloo, R.; Johnson, N.W. Poor oral health and severe mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2015, 77, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodes, G.E.; Epperson, C.N. Sex differences in vulnerability and resilience to stress across the life span. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 86, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 22 | 21.78 |

| Female | 79 | 78.22 | |

| Clinical experience (years) | Less than 5 years | 30 | 29.70 |

| 5–10 years | 10 | 9.91 | |

| 10–20 years | 31 | 30.69 | |

| More than 20 years | 30 | 29.70 | |

| Frequency of encountering patients with mental disorders | Less than 5 times per month | 82 | 81.19 |

| 5–10 times per month | 14 | 13.86 | |

| More than 10 times per month | 5 | 4.95 |

| Question | N | % | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you consider you have acquired sufficient knowledge to work with patients with mental disorders during your college education? | Yes | 13 | 12.87 | <0.001 |

| No | 88 | 87.13 | ||

| Do you consider you have sufficient knowledge about the pharmacological characteristics of medications used in the treatment of mental disorders? | Yes | 13 | 12.87 | <0.001 |

| No | 88 | 87.13 | ||

| Do you consider you can predict a patient’s level of cooperativity based on your understanding of mental disorders? | Yes | 31 | 30.69 | <0.001 |

| No | 70 | 69.31 | ||

| When taking patients’ medical histories, do you always inquire about any mental disorders? | Yes | 49 | 48.51 | 0.765 |

| No | 52 | 51.49 | ||

| When taking a patient’s medical history, do you always check if the patient is using any psychotropic medications? | Yes | 66 | 65.35 | 0.002 |

| No | 35 | 34.65 | ||

| Do you consider some of your patients struggle with drug abuse? | Yes | 77 | 76.24 | <0.001 |

| No | 24 | 23.76 | ||

| Do you consider that an underlying mental disorder affects the outcome of dental treatment? | Yes | 82 | 81.19 | <0.001 |

| No | 19 | 18.81 | ||

| Have you ever had an unpleasant experience while treating a patient with a mental disorder? | Yes | 41 | 39.60 | 0.058 |

| No | 60 | 59.40 | ||

| Have you ever consulted a specialist or general practitioner involved in a patient’s mental care during dental treatment? | Yes | 43 | 42.57 | 0.135 |

| No | 58 | 57.43 | ||

| Have you ever refused to work with a patient suffering from a mental disorder? | Yes | 15 | 14.85 | <0.001 |

| No | 86 | 85.15 | ||

| Would you like to receive additional education on the approach to patients with mental disorders? | Yes | 87 | 86.14 | |

| No | 14 | 13.86 | <0.001 | |

| Do you consider that the oral health of patients with mental disorders is at greater risk than that of the general population? | Yes | 95 | 94.06 | <0.001 |

| No | 6 | 5.94 | ||

| Do you consider early dental referral is important for maintaining the oral health of patients with mental disorders? | Yes | 97 | 96.04 | <0.001 |

| No | 4 | 3.96 | ||

| Do you consider that patients with mental disorders require professional assistance in maintaining their oral hygiene? | Yes | 95 | 94.06 | <0.001 |

| No | 6 | 5.94 | ||

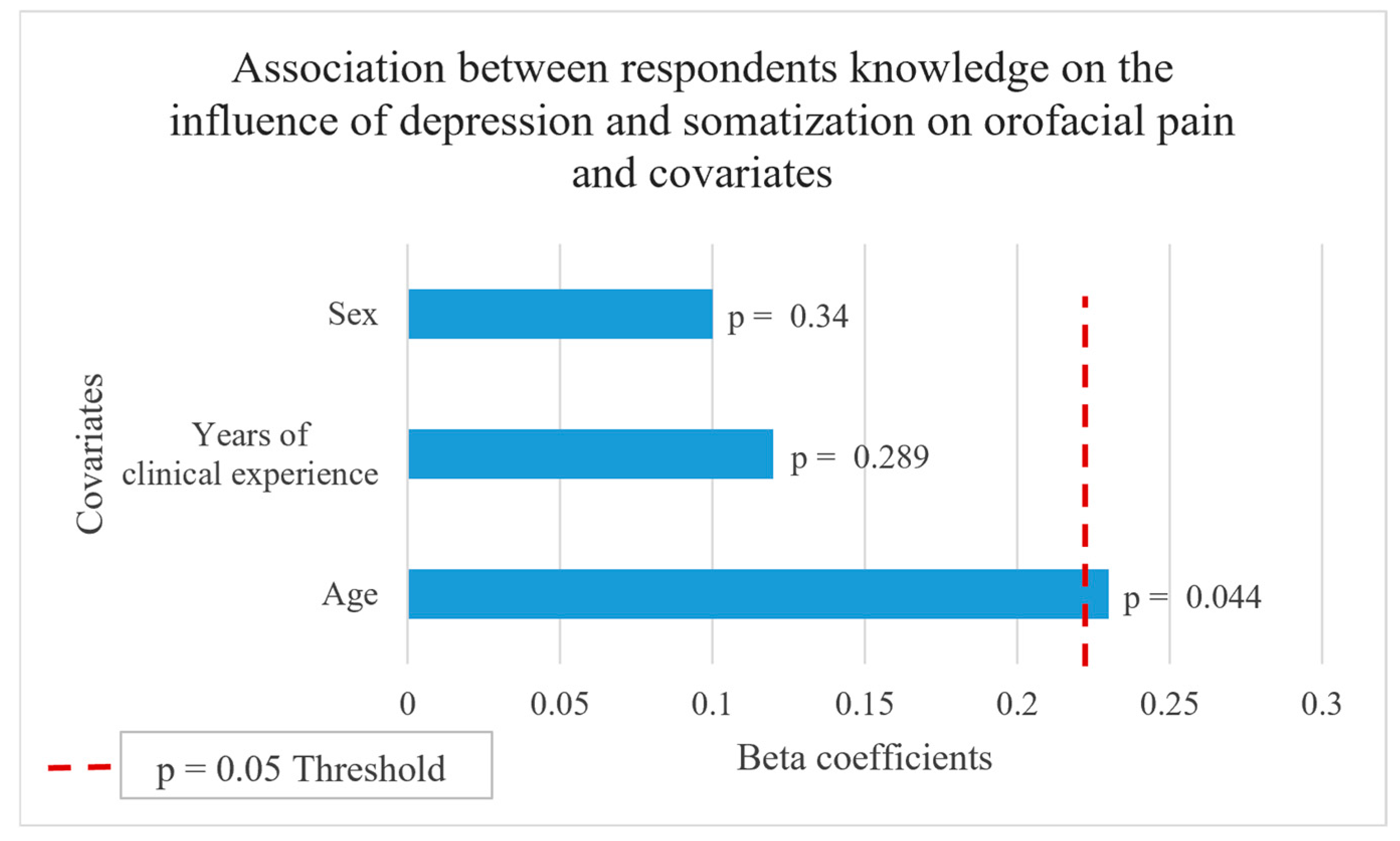

| Do you consider that depression and somatization significantly affect the diagnosis and treatment of orofacial pain? | Yes | 93 | 92.08 | <0.001 |

| No | 8 | 7.92 |

| Question | N | % | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you consider that xerostomia is the most common oral side effect of antidepressant therapy? | Yes | 59 | 58.42 | <0.001 |

| No | 7 | 6.93 | ||

| I do not know | 35 | 34.65 | ||

| Do you consider that it is necessary to take special caution during the administration of local anesthetic if the patient is taking tricyclic antidepressants? | Yes | 42 | 41.58 | 0.060 |

| No | 23 | 22.77 | ||

| I do not know | 36 | 35.64 | ||

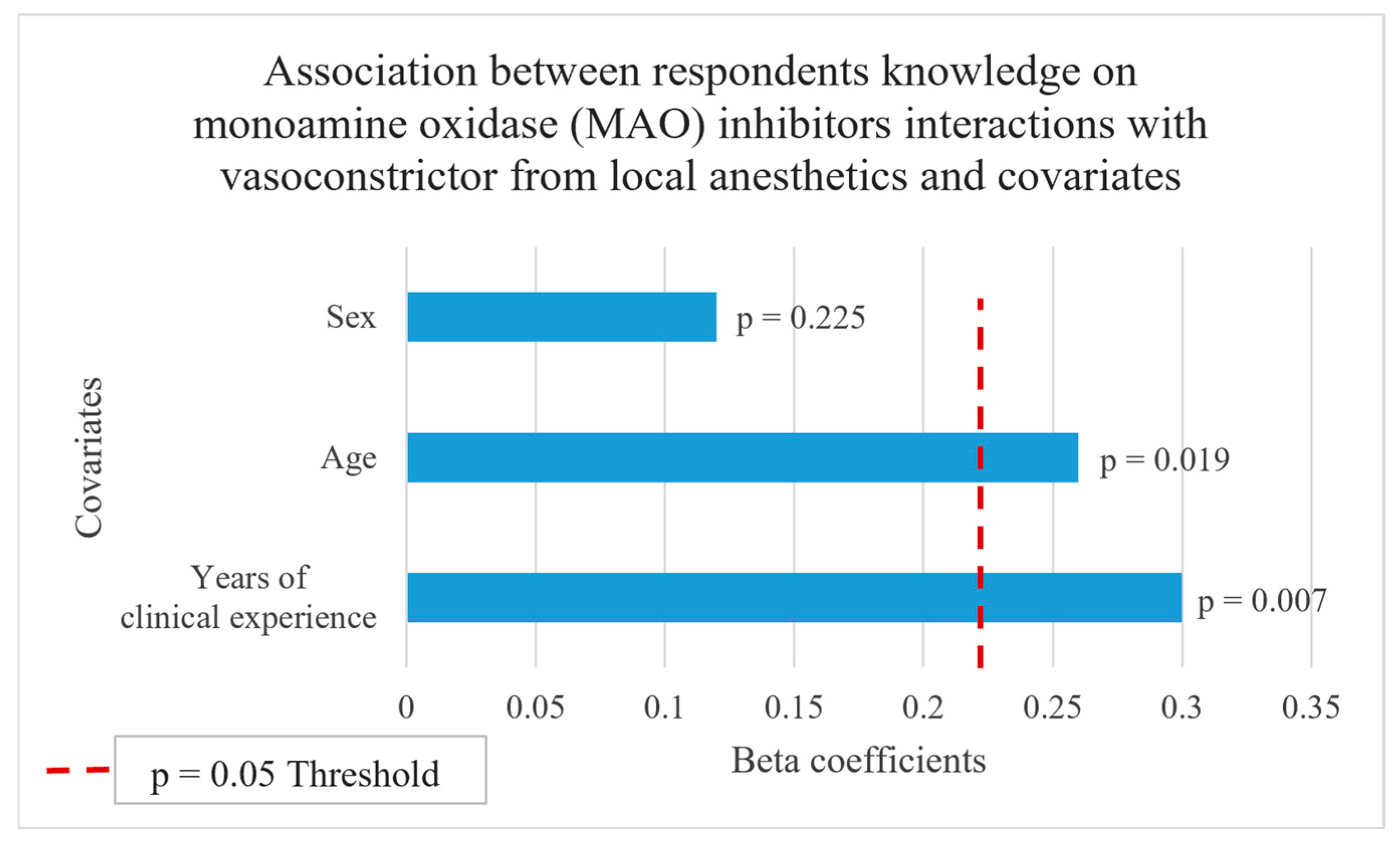

| Do you consider that taking monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors is one of the contraindications for the administration of local anesthetic with vasoconstrictor? | Yes | 58 | 57.43 | <0.001 |

| No | 15 | 14.85 | ||

| I do not know | 28 | 27.72 |

| Variable | Sum of Ranks M | Sum of Ranks F | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| During my work in the dental practice, I encounter patients dealing with any kind of mental disorders: | 1159 | 3992 | 0.658 |

| Do you consider you have acquired sufficient knowledge to work with patients with mental disorders during your college education? | 1181 | 3970 | 0.406 |

| Do you consider that you have sufficient knowledge about the pharmacological characteristics of medications used in the treatment of mental disorders? | 1181 | 3970 | 0.406 |

| Do you consider that you can predict the level of patient cooperativity based on your understanding of mental disorders? | 1236 | 3916 | 0.244 |

| When taking patients’ medical histories, do you always inquire about any mental disorders? | 987 | 4164 | 0.201 |

| When taking a patient’s medical history, do you always check if the patient is using any psychotropic medications? | 1192 | 3960 | 0.491 |

| Do you consider some of your patients struggle with drug abuse? | 1033 | 4119 | 0.320 |

| Do you consider that an underlying mental disorder affects the outcome of dental treatment? | 1014 | 4137 | 0.191 |

| Have you ever had an unpleasant experience while treating a patient with a mental disorder? | 1176 | 3975 | 0.604 |

| Have you ever consulted a specialist or general practitioner involved in a patient’s mental care during dental treatment? | 939 | 4213 | 0.078 |

| Have you ever refused to work with a patient suffering from a mental disorder? | 1210 | 3942 | 0.245 |

| Would you like to receive additional education on the approach to patients with mental disorders? | 1221 | 3931 | 0.177 |

| Do you consider that the oral health of patients with mental disorders is at greater risk than that of the general population? | 1107 | 4045 | 0.763 |

| Do you consider that early dental referral is important for maintaining the oral health of patients with mental disorders? | 1129 | 4023 | 0.883 |

| Do you consider that patients with mental disorders require professional assistance in maintaining their oral hygiene? | 1056 | 4095 | 0.188 |

| Do you consider that xerostomia is the most common oral side effect of the antidepressant therapy? | 1198 | 3953 | 0.475 |

| Do you consider that it is necessary to take special caution during the administration of local anesthetic if the patient is taking tricyclic antidepressants? | 1050 | 4102 | 0.525 |

| Do you consider that taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors is one of the contraindications for the administration of local anesthetic with vasoconstrictor? | 975 | 4176 | 0.174 |

| Do you consider that depression and somatization significantly affect the diagnosis and treatment of orofacial pain? | 1085 | 4067 | 0.515 |

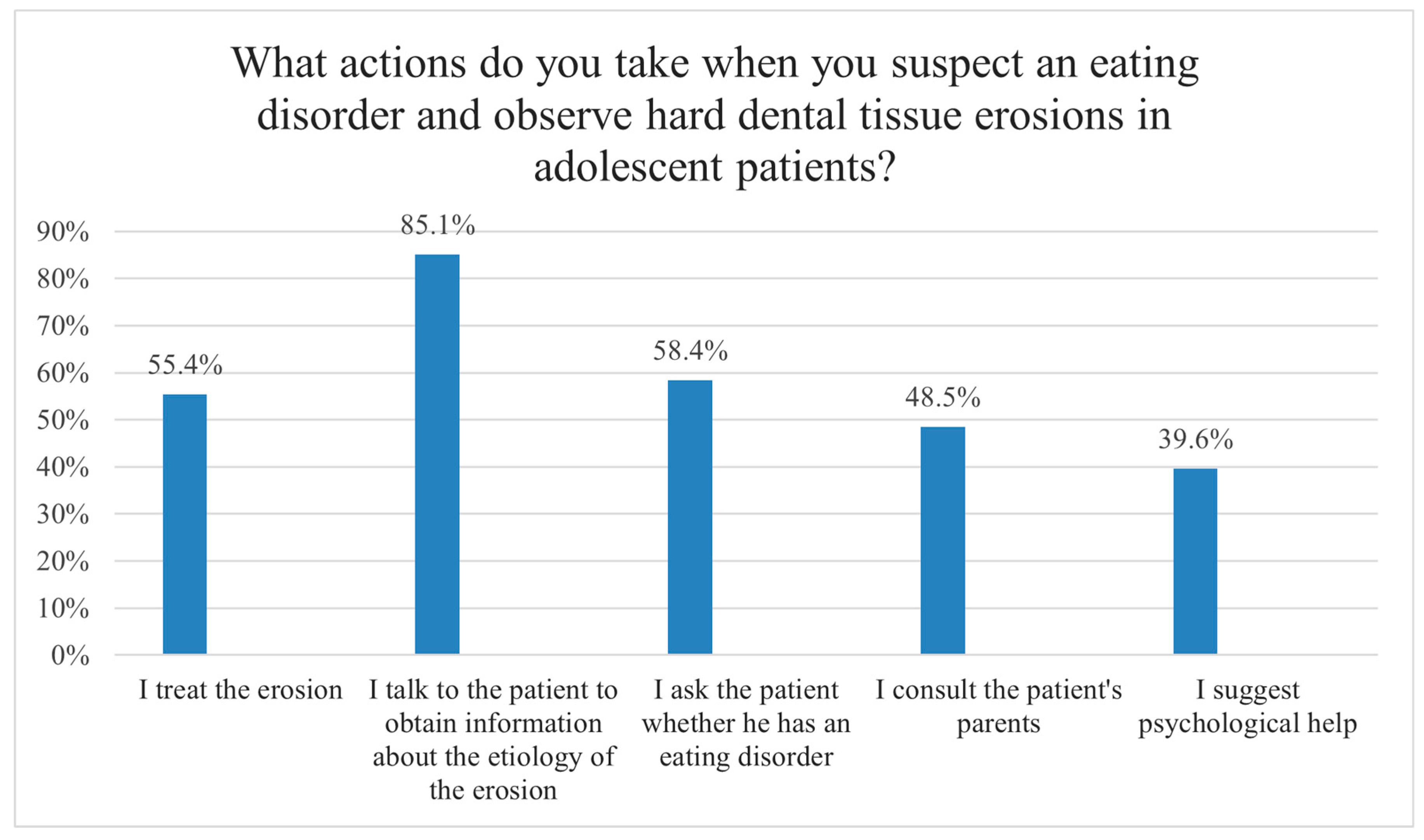

| What actions do you take when you suspect an eating disorder and observe hard dental tissue erosion in adolescent patients? (it is possible to choose multiple answers) | 1137 | 4014 | 0.904 |

| I feel uncomfortable when meeting a patient with mental disorder. | 887 | 4265 | 0.041 |

| When noticing signs of an underlying mental disorder, apart from providing dental care, dentist should refer the patient for further treatment. | 1275 | 3876 | 0.184 |

| I feel uncomfortable asking about patients’ mental health. | 954 | 4198 | 0.150 |

| I expect a low cooperativity level from a patient with a confirmed diagnosis of severe mental disorder and would rather redirect him to another dental care provider for treatment. | 1075 | 4077 | 0.688 |

| I consider that oral diseases in patients dealing with severe mental disorders deserve the same level of attention as other comorbidities. | 1123 | 4029 | 1.000 |

| I consider that patients with mental disorders in the dental practice may be classified as high-risk patients. | 1064 | 4088 | 0.614 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ninčević, B.; Tadin, A.; Žuljević, M.F.; Poklepović Peričić, T. Experiences and Attitudes Toward the Treatment of Patients with Mental Disorders Among Dentists in Croatia: A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study. Oral 2025, 5, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5030050

Ninčević B, Tadin A, Žuljević MF, Poklepović Peričić T. Experiences and Attitudes Toward the Treatment of Patients with Mental Disorders Among Dentists in Croatia: A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study. Oral. 2025; 5(3):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5030050

Chicago/Turabian StyleNinčević, Branimir, Antonija Tadin, Marija Franka Žuljević, and Tina Poklepović Peričić. 2025. "Experiences and Attitudes Toward the Treatment of Patients with Mental Disorders Among Dentists in Croatia: A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study" Oral 5, no. 3: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5030050

APA StyleNinčević, B., Tadin, A., Žuljević, M. F., & Poklepović Peričić, T. (2025). Experiences and Attitudes Toward the Treatment of Patients with Mental Disorders Among Dentists in Croatia: A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study. Oral, 5(3), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5030050