Knowledge and Attitudes of Dentists and Dental Students in the Early Diagnosis of Oral Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Descriptive Observational Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Type of Study, Population, and Sample Selection

2.2. Data Collection Instrument

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Personal Characterization

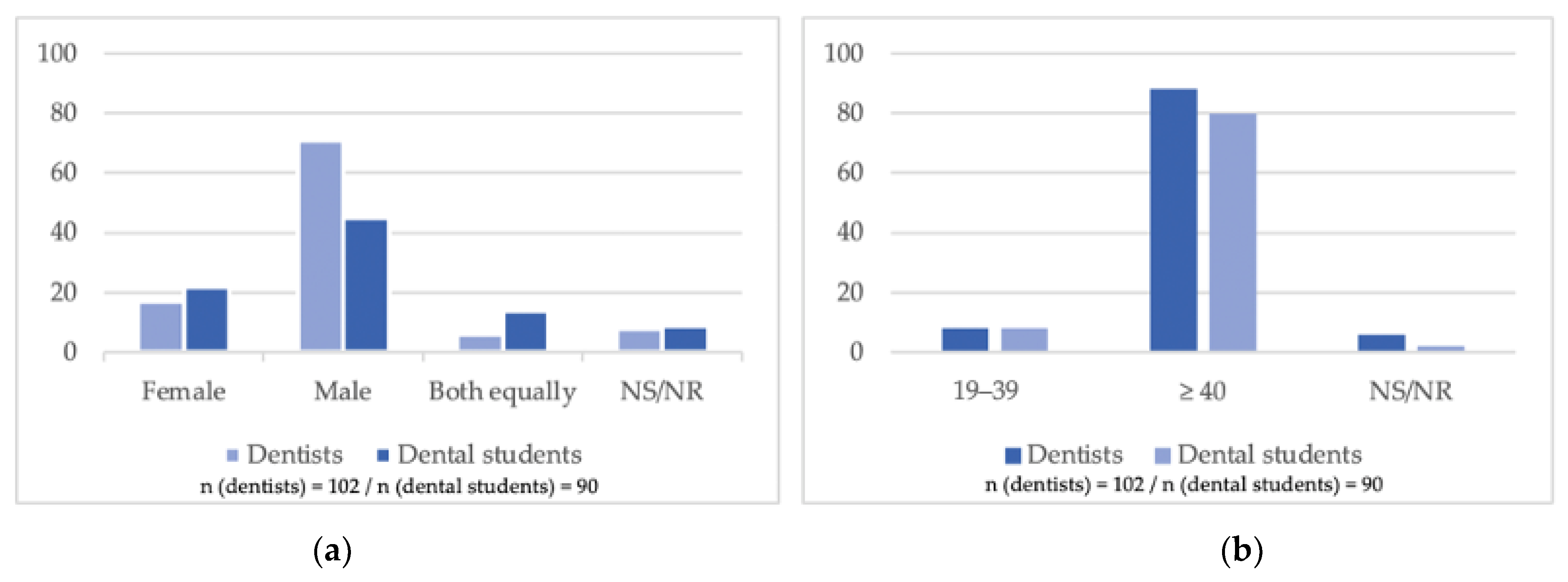

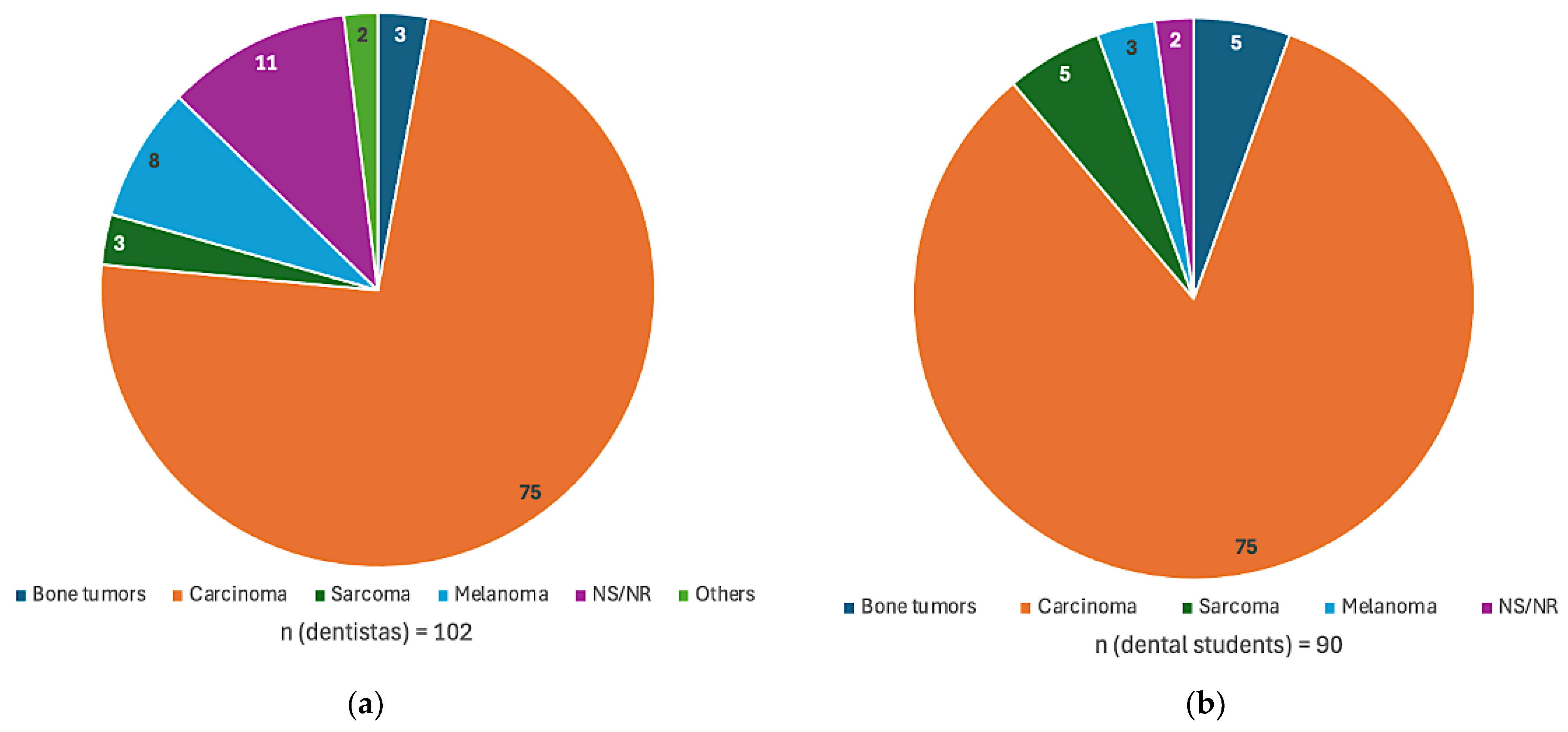

3.2. Oral Cancer and Potentially Malignant Disorders

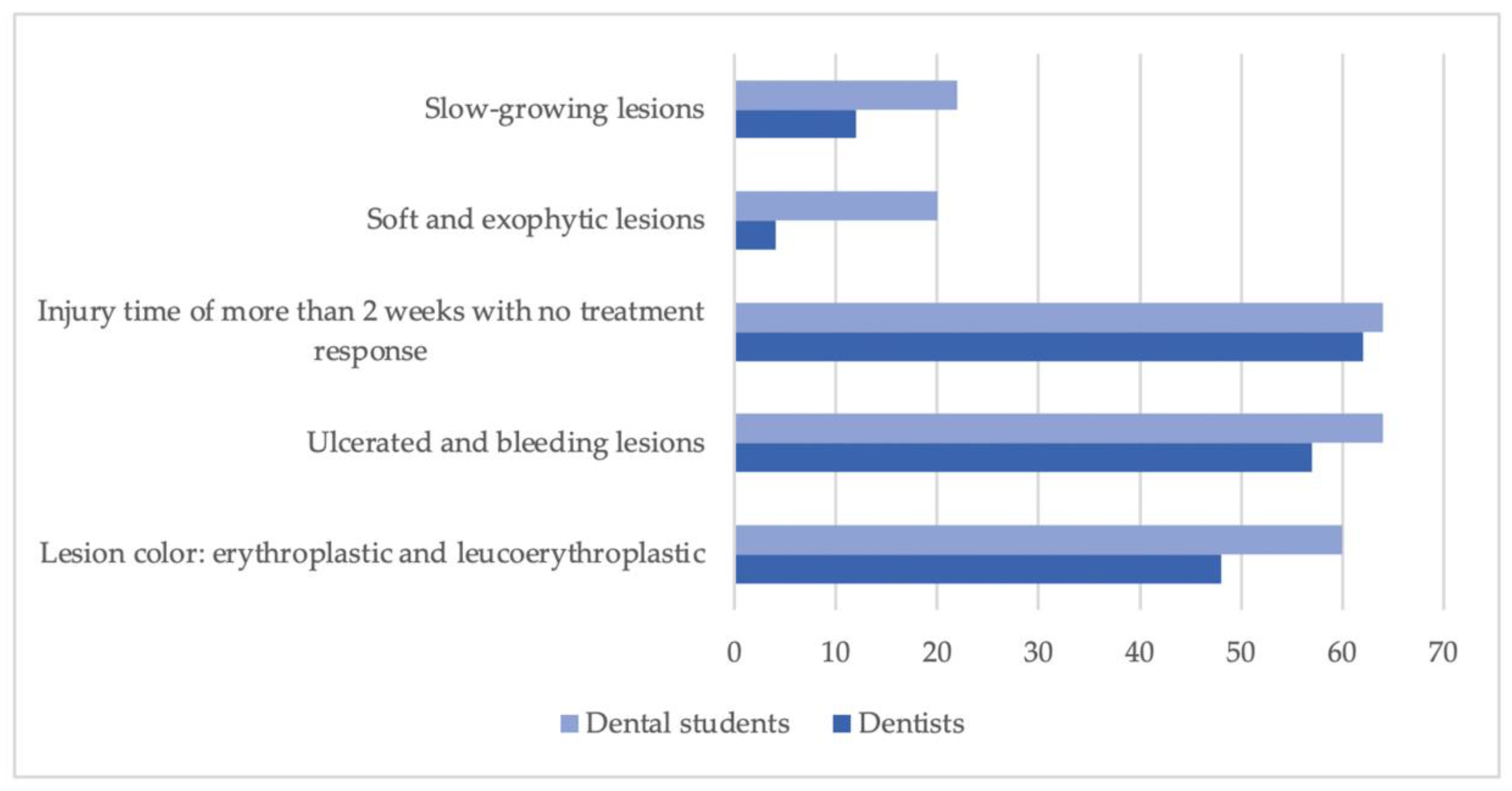

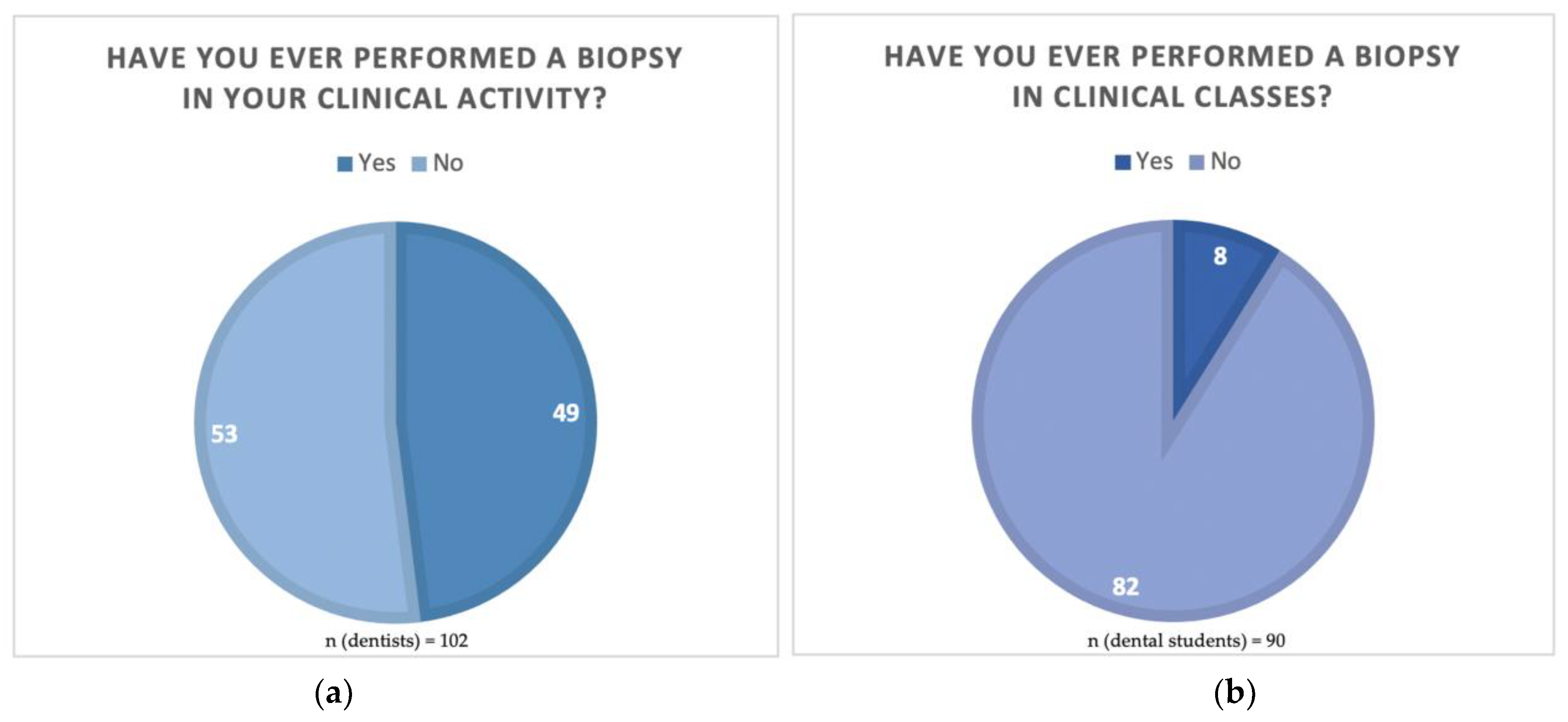

3.3. Clinical Practice in Oral Cancer Diagnosis

3.4. Personal Opinion

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumar, M.; Nanavati, R.; Modi, T.G.; Dobariya, C. Oral cancer: Etiology and risk factors: A review. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2016, 12, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, C. Essentials of oral cancer. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 11884–11894. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Neville, B.W.; Day, T.A. Oral cancer and precancerous lesions. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2002, 52, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarode, S.C.; Sarode, G.S.; Karmarkar, S. Early detection of oral cancer: Detector lies within. Oral Oncol. 2012, 48, 193194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, S.; Gueiros, L.A.; Leão, J.C.; Fedele, S. Risk factors and etiopathogenesis of potentially premalignant oral epithelial lesions. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2018, 125, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, J.; Sabiha, B.; Jan, H.U.; Haider, S.A.; Khan, A.A.; Ali, S.S. Genetic etiology of oral cancer. Oral Oncol. 2017, 70, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zygogianni, A.G.; Kyrgias, G.; Karakitsos, P.; Psyrri, A.; Kouvaris, J.; Kelekis, N.; Kouloulias, V. Oral squamous cell cancer: Early detection and the role of alcohol and smoking. Head Neck Oncol. 2011, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrero, R.; Castellsagué, X.; Pawlita, M.; Lissowska, J.; Kee, F.; Balaram, P.; Rajkumar, T.; Sridhar, H.; Rose, B.; Pintos, J. Human papillomavirus and oral cancer: The International Agency for Research on Cancer multicenter study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2003, 95, 1772–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scully, C.; Porter, S. ABC of oral health. Oral Cancer BMJ. 2000, 321, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Baykul, T.; Yilmaz, H.H.; Aydin, U.; Aydin, M.A.; Aksoy, M.; Yildirim, D. Early diagnosis of oral cancer. J. Int. Med. Res. 2010, 38, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warnakulasuriya, S.; Johnson, N.W.; van der Waal, I. Nomenclature and classification of potentially malignant disorders of the oral mucosa. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2007, 36, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, J.D.; Batstone, M.; Farah, C.S. Missed opportunities for oral cancer screening in Australia. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2019, 48, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, R.J.; Stoecker, W.V.; Moss, R.H. A relative color approach to color discrimination for malignant melanoma detection in dermoscopy images. Skin Res. Technol. 2007, 13, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rader, R.K.; Payne, K.S.; Guntupalli, U.; Rabinovitz, H.; Oliviero, M.C.; Drugge, R.J.; Malters, J.J.; Stoecker, W.V. The pink rim sign: Location of pink as an indicator of melanoma in dermoscopic images. J. Skin Cancer 2014, 2014, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, S.; Hiwale, K.; Gadkari, P.; Agrawal, A.K.; Naseri, S.; Khan, S. Beyond the norm: Navigating a unique papillary carcinoma journey in breast cancer. Cureus 2024, 16, e59795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCarthy, D.; Flint, S.R.; Healy, C.; Stassen, L.F. Oral and neck examination for early detection of oral cancer—A practical guide. J. Ir. Dent. Assoc. 2011, 57, 195–199. [Google Scholar]

- Abati, S.; Bramati, C.; Bondi, S.; Lissoni, A.; Trimarchi, M. Oral Cancer and Precancer: A Narrative Review on the Relevance of Early Diagnosis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 9160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, B.K. Oral cancer: Prevention and detection. Med. Princ. Pract. 2002, 11, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, S., Jr.; Kerr, A.R.; Epstein, J.B. Oral and pharyngeal cancer control and early detection. J. Cancer Educ. 2010, 25, 279–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horowitz, L.M.; Aiden, L.E.; Wiggins, J.S.; Pincus, A.L. Inventory of Interpersonal Problems Manual; The Psychological Corporation: Odessa, FL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee, T.; Kerketa, M.; Babu, N. Differences of oral cancer in men and women of west bengal, india. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Pathol. 2021, 25, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shigeishi, H.; Sugiyama, M. Risk factors for oral human papillomavirus infection in healthy individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2016, 8, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, K.V.V.; Suresan, V. Knowledge, attitude and screening practices of general dentists concerning oral cancer in Bangalore city. Indian J. Cancer 2012, 49, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertrampf, K.; Wenz, H.J.; Koller, M.; Grund, S.; Wiltfang, J. The oral cancer knowledge of dentists in Northern Germany after educational intervention. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2011, 20, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decuseara, G.; MacCarthy, D.; Menezes, G. Oral cancer: Knowledge, practices and opinions of dentists in Ireland. J. Ir. Dent. Assoc. 2011, 57, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bauluck-Nujoo, B.; Singh, S. Self-reported oral health status: Perspectives of patients undergoing therapy for cancer of the head and neck region, in the ethekwini district, KZN. South Afr. Dent. J. 2022, 77, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanuthai, K.; Rojanawatsirivej, S.; Thosaporn, W.; Kintarak, S.; Subarnbhesaj, A.; Darling, M.; Kryshtalskyj, E.; Chiang, C.-P.; Shin, H.-I.; Choi, S.-Y.; et al. Oral cancer: A multicenter study. Medicina Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2018, 23, e23–e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gao, F.; Yang, A.; Chen, W.; Chen, S.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Z.-Y.; Chen, X.-L.; Song, M. Epidemiologic characteristics of oral cancer: Single-center analysis of 4097 patients from the sun yat-sen university cancer center. Chin. J. Cancer. 2016, 35, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashat, M.; Puri, S.; Pandey, A.; Goel, N.; Singh, A.; Kaushal, V. Socio-demographic characteristics of cancer patients: Hospital based cancer registry in a tertiary care hospital of india. Ind. J. Cancer 2014, 51, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, F.; Miguel, A.; Dutra, K.; Porporatti, A.; Warnakulasuriya, S.; Guerra, E.; Rivero, E. Prevalence of oral potentially malignant disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2018, 47, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.M.A.W.; Ghazali, F.M.M.; Yaqoob, M.A.; Alawthah, G.H.; Srivastava, K.C.; Shrivastava, D.; Alam, M.K. A comprehensive cross-tabulation analysis of oral carcinoma patients. J. Pharm. Bioallied. Sci. 2021, 13 (Suppl. S2), S1074–S1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nath, A.; Priyanka, P.; Singh, J.K.; Singh, S.; Jain, P.; Sardhana, M.; Kumar, A.; Ranjan, S.K.; Singh, M.K. High level of estrogen in male oral cancer patients and consumption of smokeless tobacco. J. Ecophysiol. Occupat. Health 2014, 14, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Silva, S.R.J.Y.; Novo, N.F.; Weinfeld, I. Comparative study of knowledge about oral cancer among undergraduate dental students. Einstein 2016, 14, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fotedar, S.; Bhardwaj, V.; Manchanda, K.; Fotedar, V.; Sarkar, A.; Sood, N. Knowledge, attitude and practices about oral cancers among dental students in HP Government Dental College, Shimla, Himachal Pradesh. South. Asian J. Cancer 2015, 4, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uti, O.G.; Fashina, A.A. Oral cancer education in dental schools: Knowledge and experience of Nigerian undergraduate students. J. Dent. Educ. 2006, 70, 676–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öien, R.; Roxenius, J.; Boström, M.; Wickström, H. Management and outcomes among patients with hard-to-heal ulcers in sweden: A national mapping of data from medical records, focusing on diagnoses, ulcer healing, ulcer treatment time, pain and prescription of analgesics and antibiotics. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e087894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tunç, S.; Toprak, M.; Yüce, E.; Efe, N.; Topbaş, C. Comparison of knowledge, awareness, and behaviors toward oral cancer among dental students and dentists: An online cross-sectional questionnaire in Türkiye. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafer, M.; Crutzen, R.; Moafa, I.; Borne, B. What do dentists and dental students think of oral cancer and its control and prevention strategies? a qualitative study in jazan dental school. J. Cancer Educ. 2019, 36, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafer, M.; Crutzen, R.; Halboub, E.; Moafa, I.; Borne, B.; Bajonaid, A.; Jafer, A.; Hedad, I. Dentists behavioral factors influencing early detection of oral cancer: Direct clinical observational study. J. Cancer Educ. 2022, 37, 932–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanaras, N.; Warnakulasuriya, S. Oral cancer diagnosis in primary care. Prim. Dent. J. 2016, 5, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Guo, L.; Chen, S.W.; Zhao, X.H.; Zhuang, S.M.; Wang, L.P.; Song, L.B.; Song, M. GOLPH3 overexpression correlates with tumor progression and poor prognosis in patients with clinically N0 oral tongue cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2012, 10, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essat, M.; Cooper, K.; Bessey, A.; Clowes, M.; Chilcott, J.B.; Hunter, K.D. Diagnostic accuracy of conventional oral examination for detecting oral cavity cancer and potentially malignant disorders in patients with clinically evident oral lesions: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck 2022, 44, 998–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colella, G.; Gaeta, G.M.; Moscariello, A.; Angelillo, I.F. Oral cancer and dentists: Knowledge, attitudes, and practices in Italy. Oral Oncol. 2008, 44, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, B.; Subedi, S. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Oral Biopsy Procedures among Dental Surgeons Registered with Nepal Dental Association. J. Nepal Health Res. Counc. 2020, 18, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clinical Observation | Description |

|---|---|

| Color | Completely erythematous lesions or those with a leukoplastic or erythroplastic component |

| Ulceration | Ulcerated or erosive lesions that do not heal |

| Duration | More than 2 weeks |

| Growth | Quickly |

| Bleeding | Easily hemorrhagic |

| Hardening | Hard on palpation |

| Fixing | Adhered to adjacent structures |

| Parameter | % Dentists Agreeing | % Students Agreeing | Difference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male Gender | 60% | 50% | 10% |

| <30 Years Old | 10% | 90% | 80% |

| Correctly identify high-risk sites | 95% | 85% | 10% |

| Know common PMDs (e.g., leukoplakia) | 100% | 80% | 20% |

| Identify tobacco as a risk factor | 100% | 100% | 0% |

| Include mucosa, tongue, palate, etc., in exam | 100% | 90% | 10% |

| Palpate head/neck lymph nodes | 90% | 70% | 20% |

| Guide patients on self-exam | 60% | 50% | 10% |

| Routinely examine for oral cancer | 95% | 85% | 10% |

| Have performed biopsy | 80% | 10% | 70% |

| Refer suspicious lesions | 90% | 80% | 10% |

| Rate diagnostic ability as high | 70% | 40% | 30% |

| Rate biopsy ability as high | 60% | 20% | 40% |

| See dentists as crucial in prevention | 100% | 100% | 0% |

| Dentists | Dental Students | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | Female | 66 | 64.7% | 58 | 64.4% | 124 | 64.5% |

| Male | 36 | 35.3% | 32 | 35.6% | 68 | 35.5% | |

| Age | 21–30 years | 32 | 31.4% | 83 | 92.2% | 115 | 59.8% |

| 31–40 years | 24 | 23.5% | 5 | 5.6% | 29 | 15.2% | |

| 41–50 years | 31 | 30.4% | 2 | 2.2% | 33 | 17.2% | |

| +50 years | 15 | 14.7% | 0 | 0% | 15 | 7.8% | |

| Nationality | Portuguese | 64 | 62.7% | 57 | 63.3% | 121 | 63.0% |

| Brazilian | 36 | 35.3% | 11 | 12.2% | 47 | 24.5% | |

| Spanish | 1 | 1.0% | 7 | 7.8% | 8 | 4.2% | |

| Italian | 1 | 1.0% | 11 | 12.2% | 12 | 6.3% | |

| Other | 0 | 1.0% | 4 | 4.4% | 4 | 2.0% | |

| Dentists | Dental Students | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Sites associated with greater potential for malignancy | Tongue | 73 | 71.6% | 76 | 84.4% | 149 | 34.7% |

| Floor of the mouth | 49 | 48.0% | 59 | 65.6% | 108 | 25.3% | |

| Jugal mucosa | 31 | 30.4% | 40 | 44.4% | 71 | 16.6% | |

| Alveolar ridge | 8 | 7.8% | 3 | 3.3% | 11 | 2.5% | |

| Gingiva | 4 | 3.9% | 4 | 4.4% | 8 | 1.8% | |

| Hard palate | 8 | 7.8% | 22 | 24.4% | 30 | 7.0% | |

| Soft palate | 19 | 18.6% | 33 | 6.7% | 52 | 12.1% | |

| Potentially malignant disorders | Traumatic fibroma | 7 | 6.9% | 13 | 14.4% | 20 | 3.7% |

| Leukoplakia | 70 | 68.6% | 61 | 67.8% | 131 | 24.6% | |

| Traumatic white lesions | 19 | 18.6% | 12 | 13.3% | 31 | 5.8% | |

| Erythroplakia | 48 | 47.1% | 51 | 56.7% | 99 | 18.6% | |

| Erosive lichen planus | 33 | 32.4% | 52 | 57.8% | 85 | 16.2% | |

| Lupus | 3 | 2.9% | 7 | 7.8% | 10 | 1.8% | |

| Chronic candidiasis | 6 | 5.9% | 12 | 13.3% | 22 | 4.1% | |

| Actinic cheilitis | 17 | 16.7% | 17 | 18.9% | 34 | 6.6% | |

| Inverted smoker’s palate | 34 | 33.3% | 65 | 72.2% | 99 | 18.6% | |

| Risk factors associated with oral cancer | Tobacco | 94 | 92.2% | 85 | 94.4% | 179 | 25.8% |

| Alcohol | 66 | 64.7% | 61 | 67.8% | 127 | 18.3% | |

| Obesity | 6 | 5.9% | 21 | 23.3% | 27 | 3.8% | |

| HPV subtype 16 and 18 | 38 | 37.3% | 45 | 50.0% | 83 | 11.9% | |

| HPV subtype 6 11 | 25 | 24.5% | 26 | 28.9% | 51 | 7.3% | |

| Potentially malignant lesions | 49 | 48.0% | 70 | 77.8% | 119 | 17.2% | |

| Hypertension | 1 | 1.0% | 2 | 2.2% | 3 | 0.44% | |

| Cholesterol | 1 | 1.0% | 2 | 2.2% | 3 | 0.44% | |

| Exposure to UV radiation | 35 | 34.3% | 50 | 55.6% | 85 | 12.4% | |

| Herpes simplex virus | 7 | 6.9% | 9 | 10.0% | 16 | 2.5% | |

| In the intraoral examination, does it include evaluation of the mucous membranes, tongue, palate, floor, and retromolar region? | Yes | 97 | 95.1% | 85 | 94.4% | 182 | 94.7% |

| No | 5 | 4.9% | 5 | 5.6% | 10 | 5.3% | |

| In the extraoral examination, do you palpate the lymph nodes in the head and neck region? | Yes | 65 | 63.7% | 73 | 81.1% | 138 | 71.8% |

| No | 37 | 36.3% | 17 | 18.9% | 54 | 28.2% | |

| Do you try to guide the patient in oral self-examination? | Yes, to all patients | 31 | 30.4% | 34 | 37.8% | 65 | 33.8% |

| Yes, but only patients at risk | 37 | 36.3% | 25 | 27.8% | 62 | 32.4% | |

| No | 34 | 33.3% | 31 | 34.4% | 65 | 33.8% | |

| Dentists | Dental Students | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| How do you rate your ability to make a clinical diagnosis of a potentially malignant lesion or oral cancer? | I don’t feel comfortable | 30 | 29.4% | 9 | 10.0% | 39 | 20.3% |

| Fair | 37 | 36.3% | 50 | 55.6% | 87 | 45.4% | |

| Good | 27 | 26.5% | 28 | 31.1% | 55 | 28.5% | |

| Very good | 5 | 4.9% | 3 | 3.3% | 8 | 4.2% | |

| NR | 3 | 2.9% | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 1.6% | |

| How do you rate your ability to perform a biopsy? | I don’t feel comfortable | 46 | 45.1% | 20 | 22.2% | 66 | 34.3% |

| Fair | 25 | 24.5% | 44 | 48.9% | 69 | 35.9% | |

| Good | 23 | 22.3% | 23 | 25.6% | 46 | 23.8% | |

| Very good | 5 | 4.9% | 3 | 3.3% | 8 | 4.5% | |

| NR | 3 | 2.9% | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 1.5% | |

| In your opinion, how important is a dentist in the prevention and detection of oral cancer? | Irrelevant | 2 | 2.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 1.2% |

| Important, but not primarily responsible | 4 | 3.9% | 8 | 8.9% | 12 | 6.2% | |

| Very important | 93 | 91.2% | 82 | 91.1% | 175 | 91.1% | |

| NR | 3 | 2.9% | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 1.5% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silva, M.M.; Vozzo, L.M.; Marques, T.; Veiga, N.; Fernandes, J.C.H.; Fernandes, G.V.O.; Couto, P. Knowledge and Attitudes of Dentists and Dental Students in the Early Diagnosis of Oral Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Descriptive Observational Study. Oral 2025, 5, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5020043

Silva MM, Vozzo LM, Marques T, Veiga N, Fernandes JCH, Fernandes GVO, Couto P. Knowledge and Attitudes of Dentists and Dental Students in the Early Diagnosis of Oral Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Descriptive Observational Study. Oral. 2025; 5(2):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5020043

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva, Maria Miguel, Lucrezia Maria Vozzo, Tiago Marques, Nélio Veiga, Juliana Campos Hasse Fernandes, Gustavo Vicentis Oliveira Fernandes, and Patrícia Couto. 2025. "Knowledge and Attitudes of Dentists and Dental Students in the Early Diagnosis of Oral Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Descriptive Observational Study" Oral 5, no. 2: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5020043

APA StyleSilva, M. M., Vozzo, L. M., Marques, T., Veiga, N., Fernandes, J. C. H., Fernandes, G. V. O., & Couto, P. (2025). Knowledge and Attitudes of Dentists and Dental Students in the Early Diagnosis of Oral Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Descriptive Observational Study. Oral, 5(2), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5020043